The anthropogenic impact and the pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the largest health and humanitarian crises in over a century. This disease, caused by the virus SARS-CoV-2, began in the city of Wuhan, province of Hubei, China, in December of 2019, and after more than a year we continue struggling to control the disease and mitigate its social, economic, political, educational and scientific impacts. In this sense, although the severity of the impact of the ongoing pandemic varies from one country to the next, in general terms, poverty and inequality increased and global food security was jeopardized. The mobility restrictions worldwide led to the delay or reduction of harvests, especially in local farms, since food industries put their activities on hold and the closing of borders limited the imports of agricultural inputs, as well as the exports of foods. On the other hand, the reduction or loss of economic incomes in families and the rising food costs limited the access to the latter (FAO, 2020).

However, COVID-19 is not our only problem nowadays, since humanity was facing its greatest challenge in the 21st century, even before the pandemic began: the global anthropogenic impact, i.e. climate change, the deterioration of soils and ecosystems, the alteration of biogeochemical cycles, overexploitation of natural resources, air, and water pollution, the proliferation of invasive species, the loss of biodiversity, and others. These changes were generated and have become aggravated by human activities, causing the deterioration of ecosystems and agroecosystems (the reduction of fertile areas for agriculture). On the other hand, the increase of human interactions with the animal kingdom through the alteration of their natural habitats by the expansion of agriculture, animal husbandry, and urban areas also increases the incidents and severity of pandemics. This displays the interconnection of environmental problems with the incidence of zoonotic diseases (Lal, 2020). Therefore, due to this interconnection, the effects of COVID-19, health measures, and emergency closures to prevent viral transmission and contagion had direct consequences on the operation of food systems.

To mitigate the negative effects caused by the current pandemic, it is crucial to counteract these problems from a multidisciplinary standpoint that integrates the knowledge on human, animal, and environmental health. In addition, the creation of actions and strategies that contribute to the fight against COVID-19 and the mitigation of its negative effects on food security and national sovereignty is also necessary. Some forecasts suggest a drastic increase in the demand and prices of some food products after the pandemic, and consequently, the overexploitation of agroecosystems, which will lead to higher economic, environmental, and health costs for the agricultural sector (HLPE, 2020; OECD, 2020). In this context, several institutions and laboratories in the world have strengthened their research projects focused on the development of sustainable agro-biotechnological alternatives to contribute to food security for the present and future, to mitigate the effects of the current pandemic and potential pandemics in the light of negative global environmental impacts. Among the diverse strategies studied are sustainable soil management, new genetic crop varieties, the efficient use of agricultural inputs, and the use of microbial resources for the production of biofertilizers and biopesticides.

Microorganisms with the ability to interact with crops, regulating their growth and productivity through their tolerance to biotic and abiotic stress, the improvement of plant nutrition, and the antagonism of phytopathogens are called plant growth promoters (MPCV) (de los Santos-Villalobos et al., 2018; Valenzuela-Ruiz et al., 2018; Díaz-Rodríguez et al., 2021). During the current pandemic, food production has been threatened due to the limited imports of agro-inputs, particularly nitrogenized fertilizers from China, also due to the closure of international markets. Thus, the use of MPCV has been highlighted as an important strategy in sustainable agriculture, since these microorganisms have the ability to increase crop yields (~ 10-30%), with a lower dependency on agro-inputs, hence reducing the economic and environmental cost of agricultural production (Parewa et al., 2018). Therefore, the bioprospection of the microbiota present in agroecosystems for the production of biofertilizers and biopesticides is a sustainable alternative to guarantee food security, even under the diverse scenarios previously presented in this pandemic.

Soils, including those used for agriculture, are reservoirs for all types of microorganisms, including potential pathogens for humans; therefore, the imbalance in microbial ecology in this matrix gives rise to diseases (Mendes et al., 2013). For this reason, it is important to preserve the soil and use beneficial microorganisms found in the soil to maintain its homeostasis and resilience, minimizing the probability of the emergence of pathogens in humans. On the other hand, due to the appearance of worldwide biological problems, food insecurity, and the constant discovery of new microbial species or subspecies, there is a need to study microorganisms at all levels, including their bioprospection as a source of metabolites with anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity. Such is the case of ivermectin, derived from the bacteria Streptomyces avermitilis, which was reported as an inhibitor of the replication of this type of virus in vitro (Abdelmohsen et al., 2014; Caly et al., 2020). Later studies indicated that the probability of success of clinical trials with the approved dose of ivermectin is low, and the treatment based only on this medication is not ideal (Schmith et al., 2020). However, this is part of the research advance towards new treatments against COVID-19. In this way, the actions taken by the diverse research teams, particularly those with the generation of lines of knowledge related to biotechnology and the identification of beneficial microorganisms, as well as their metabolites for the solution of these problems, are crucial to contribute towards the generation of alternatives that mitigate the direct and indirect impact of the ongoing pandemic. In the same way as all other institutions in the country and the world, the LBRM-COLMENA Research Node changed in the way in which scientific research was conducted, as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The present work aims to share the experiences of our work team during the ongoing health contingency, as well as the strategies implemented to continue with research projects focused on the generation of knowledge in different scientific disciplines.

The impact of COVID-19 on the activities of LBRM-COLMENA Research Node

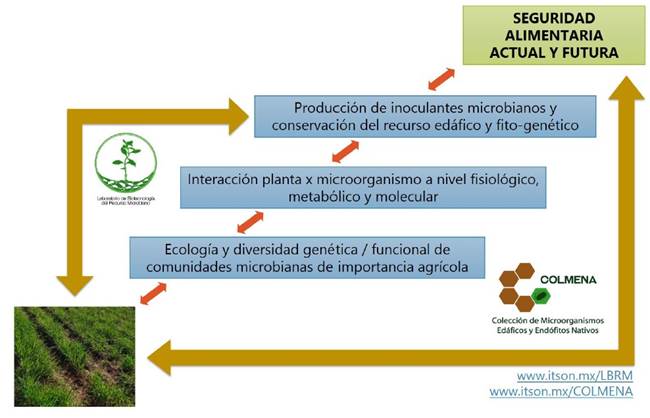

The Laboratorio de Biotecnología del Recurso Microbiano-Colección de Microorganismos Edáficos y Endófitos Nativos (LBRM-COLMENA) Research Node, of the Instituto Tecnológico de Sonora, is focused on the study of the native microbiota at an ecological, physiological, metabolic and genomic level, as well as its interactions with the main agricultural crops in Mexico, preserving this agro-biotechnological resource ex situ (Figure 1). The aim of this Research Node is to develop sustainable agro-biotechnological alternatives - based on the use of native microorganisms- to increase agricultural competitiveness of the Mexican northwest and the entire country, reducing the microbial deterioration of agricultural soils under current edaphoclimatic conditions and in the face of climate change (https://www.itson.mx/lbrm and https://www.itson.mx/colmena) (de los Santos-Villalobos et al., 2018).

Figure 1 Lines of research developed in the LBRM-COLMENA Research Node focused on contributing to food security.

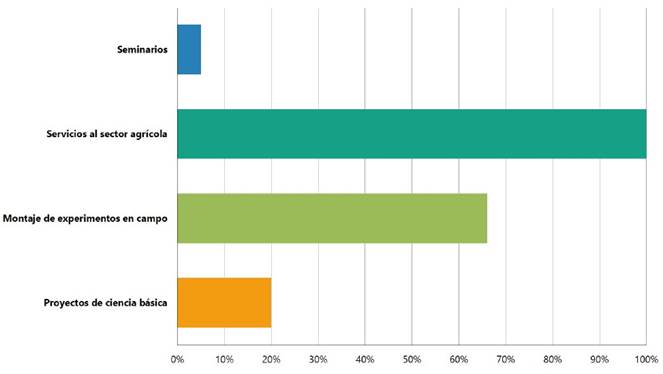

The research projects developed in the LBRM-COLMENA Research Node are based on the broad collaboration with institutes throughout Mexico and abroad, creating bonds between basic science and applied science. However, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic changed the guidelines and regulations in all sectors, including educational institutions, cooperating sectors, and scientific networks, due to the social distancing and confinement recommendations. This displayed the fragility of current knowledge-generating systems, which were almost exclusively supported by our physical presence in offices, laboratories and, public and private educational and research centers. In addition, all important agreements, conferences, symposia, courses, and seminars were held in person, which had to change to adapt to our new reality. In this way, some projects, activities, and services offered by LBRM-COLMENA Research Node were negatively affected by the pandemic (Figure 2). For example, the production of microbial inoculants (biofertilizers and biopesticides) and other services stood completely still, starting in March 2020.

The impact of COVID-19 on the human resources of LBRM-COLMENA Research Node

LBRM-COLMENA Research Node is composed of visiting (11), Bachelor’s (13), Master’s (nine), and Ph.D. students (three), out of which, 62% are women (three mothers) and 38% men (four fathers). In addition, they mainly come from different cities in Sonora, Sinaloa, Baja California, and Durango. One of the first strategies to reduce the contagion and spreading of the ongoing pandemic was to reduce the mobility of students and stay home. This action, considered important for the proposed objectives, had a considerable impact on the family component since the virtual/remote schooling of one or more family members lead to a not-so-clear separation of functions. This led some students to attend to their professional obligations, but also to housework and their schoolwork, as well as their children’s schoolwork, which did away with a standard working schedule and created different complications. This, in turn, produced an environment of greater mental burden and uncertainty with psychological consequences, and sometimes, with episodes of the disease suffered by a family member or themselves. In this sense, the team members working on their dissertations underwent the pressure of not being able to make progress with their research projects, despite the fact that the scholarship period progressed, fearing that they would not finishing their studies in a proper and timely manner.

On the other hand, the members of LBRM- COLMENA Research Node had to adapt to the remote modality to continue their work, with everything it implied: the cancellation of training courses, the modification of their contents to be presented remotely, and in general, academic-scientific plans had modifications like never before. In addition, the measurements and collection of field data, and some lab experiments had to continue in some way or another, albeit with difficulties, following adequate health and safety measures, and always making the health of those involved their priority. The foregoing, due to the need to obtain results to meet the objectives presented before and/or during the pandemic, since, in some cases, projects and scholarships had no extension periods. However, this was not the case for the meetings and projects of our work team, which involved international collaborations, due to geopolitical and economic differences.

The impact of COVID-19 on the productivity of LBRM-COLMENA Research Node

The contingency has shown the resilience of the collaborative work teams, highlighting some positive aspects of the emergency closure of institutions. For example, the increase in scientific productivity, since the total of work hours was reduced, leaving more time for the analysis of previously obtained data and the writing of manuscripts (Myers et al., 2020). In this sense, in our work team, like in many others throughout the country and the world, the contingency period and the extended time at home were used to analyze data and write scientific articles, dissertations, and projects. However, we must be aware that this productivity reflects years of work (pre-pandemic); therefore, the consequences of the pandemic in scientific research will become evident in the years after the pandemic, when there is insufficient information or data to publish due to the limited access to academic institutions and the reduction of budgets.

In this sense, a survey conducted between May and June of 2020 by Rijis and Fenter (2020) and answered by a total of 25,307 people, including health professionals, Ph.D. students, and researchers from 152 countries, indicated that 70% of researchers were able to continue with the majority of their activities, 20% indicated that their professional activities changed completely, and the rest considered that their work was not affected by the pandemic. On the other hand, 74% reported that their most common activity during this was writing scientific articles for publication, whereas 57% continued with their investigation. In addition, the study highlighted the differences perceived by people regarding the ability of their organizations and country for remote work, or if they considered that the advice of the scientific community is taken into account in the decision-making in their country; for example, in New Zealand, 75% of people consider that their institution was adequately prepared for remote work, whereas in Brazil, only 36% of the people surveyed had the same opinion about their organization; in the United States, 66% did not believe that politicians had taken science-based advice into account, whereas in Mexico, 42% have the same opinion and in China, by contrast, only 14% think in the same way.

In our work team, productivity and communication among team members were consolidated through remote seminars. In this way, collaborations were reinforced with other work teams from different institutions and countries, strengthening and forming more research networks, and getting better feedback for the results of our projects. In this sense, despite the suspension of work-stay programs and academic conferences, we were able to create and attend training programs, workshops, and conferences that were held on virtual platforms, helping us reach a greater number of participants and make the material electronically available. For instance, every summer, the LBRM-COLMENA Research Node opens its doors to students from different states and countries for scientific visits (Figure 3). Despite pandemic-related complications, in the summer of 2020, students were accepted to enter the laboratory in a remote modality. The students became engaged in projects related to bioinformatics, where they were trained in sequencing techniques and the correct taxonomic affiliation of different microorganisms of agronomical interest (biological control agents and promoters of plant growth). Thus, due to the ongoing pandemic, guaranteeing education and projects in laboratories and experimental fields at a distance (with greater complexity) was crucial; therefore, the research team leaders were creative and developed courses to simulate research experiences at those levels to strengthen abilities and the resolution of problems.

Conclusions

COVID-19 has had a global impact, and it has been estimated that it may not be the last pandemic to wreak havoc at a similar scale. Governments must invest in all areas of knowledge with collaborative, dynamic, and transdisciplinary approaches between the different sectors of society to make informed decisions; meanwhile, society (the academic-scientific sector being no exception) must be resilient to the ongoing pandemic and its impacts. Given all this, it is crucial to:

a)Look after our health. We must prioritize our health and other people’s health. Have a healthy diet and stay active but also look after our mental health, since the pandemic triggered conditions of stress and anxiety.

b)Maintain social relations and create new interpersonal relations. Despite social distancing, technological media have allowed us to have personal and work conversations. Aside from work relations, in these times it is important to create relations of support, trust, and optimism with friends, families, and colleagues.

c)Change our habits, schedules, and workplaces. Having an established schedule may be very useful to be more productive, particularly when working from home. The best is to have a time limit for working and include time for breaks, spending time with family, and leisure. During the pandemic, productivity may be frustrating, since the pace or efficiency of work is not the same as it was before the pandemic.

d)Set goals and timelines for work teams. Due to the current situation, it is very likely that we reconsider our professional goals and adapt them to the new conditions. Occasional meetings can be held for each work team to strengthen bonds between the members, measure the progress, and tackle the challenges of the research projects.

e)Be responsible. We must look out for trustworthy news, follow the established health and safety measures and look after our health and other people’s health. We must understand that the reported statistics mean the lives of people and not just numbers and that we, as a society, play a crucial role in the reduction of infection. We must also avoid the distribution of fake or unverified information to avoid the disinformation of society in the face of the current pandemic.

Finally, one aspect worth considering to prevent future pandemics and their negative impact is to ensure the biological integrity of our planet for present and future generations. This means that the government of each country and each one of us must work together via different disciplines and sectors of society, not just to monitor, prevent and reduce the appearance of zoonotic diseases, but also to prioritize the conservation of ecosystems, including agroecosystems, since these provide a fundamental structure for life and health.

text in

text in