Highlights:

The study sites were Cerro El Peñon Blanco and Sierra de Guanamé and Sierra La Mojonera.

Astraeus aff. hygrometricus was associated with Quercus potosina, Q. pringlei, Q. tinkhamii and Q. striatula.

The ectomycorrhizal association was found in friable soils with pH 5 to 7.7.

The ectomycorrhizal association contributes to the survival of oak forests under semiarid environments.

Introduction

In Mexico, the genus Quercus L. provides a wide variety of ecosystem, economic, and social services (Galicia et al., 2018; Wallace et al., 2015). Some oak species grow and develop in dry climate regions (Villarreal, Encina, & Carranza, 2008). In these areas with a water-restrictive nature, it is important to consider ectomycorrhizal symbiosis (Smith & Read, 2008). Ectomycorrhizal (ECM) fungi are an essential component in most forested communities (Tedersoo, Suvi, Larson, & Koljalg, 2006), because they are involved in nutrient cycling and ecosystem function (Cheeke et al., 2017). Studies of ECM that succeed in semi-arid relict oak ecosystems are scarce.

Astraeus hygrometricus (Pers.) Morgan has been shown to establish ectomycorrhizal symbiosis with the genus Quercus (Kayama & Yamanaka, 2014, 2016). Because of its high nutritional, economic and commercial value, the immature stages of this species are widely consumed in several Southeast Asian countries, including Thailand, India and China (Biswas, Nandi, Kuila, & Acharya, 2017; Fangfuk et al., 2010). This species is known for its mycochemical contents with medicinal properties (Biswas et al., 2017), as well as for its positive effect on root elongation, aboveground growth, nutrition and photosynthesis of Quercus species under diverse soil conditions (Kayama & Yamanaka, 2014, 2016; Makita, Hirano, Yamanaka, Yoshimura, & Kosugi, 2012).

In Mexico, A. hygrometricus is associated with oak, oak-pine, oak-juniper-pine, low deciduous forest, subtropical scrub, and gallery forest (Aguilar-Aguilar, González-Mendoza, & Grimaldo-Juárez, 2011; Esqueda et al., 2009, 2011, 2012; Párdave, Flores, Franco, & Robledo, 2007; Piña-Páez, Esqueda, Gutiérrez, & González-Ríos, 2013; Quiñónez et al., 2008). However, the study of these fungi has received little attention in the arid and semi-arid regions of the country, including the Altiplano Potosino, where fungi are distributed mainly in the mountain ranges (Sabás-Rosales, Sosa-Ramírez, & Luna-Ruiz, 2015).

Because of its high ecological, biotechnological and economic potential, as well as its potential value as food, and the scarce information on the ectomycorrhizal association, the present research aimed to know the morphology of A. aff. hygrometricus associated with Quercus species in three sites with scarce precipitation in the Altiplano Potosino.

Materials and methods

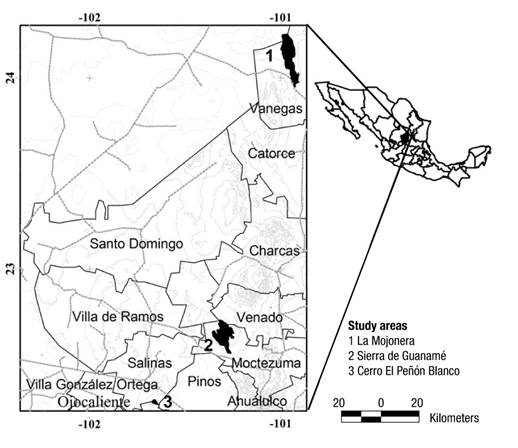

The research was carried out in the localities of Cerro El Peñón Blanco (PB), Sierra de Guanamé (SG) and Sierra La Mojonera (SM), located in the municipalities of Salinas, Venado and Vanegas, and San Luis Potosí, respectively. It should be noted that a portion of the Mountain Range La Mojonera belongs to the municipality of Concepción del Oro, Zacatecas (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Location of the study area in the Altiplano Potosino, Mexico, where associations of Astraeus aff. hygrometricus grow.

Macro and microscopic characterization of A. aff. hygrometricus

In spring and summer of 2014 and 2015, specimens of A. aff. hygrometricus were collected in each of the three study sites thriving under the shaded area of arboreal and shrubby oak forests. The laciniae were counted and the diameter of the exoperidium and endoperidium of 10 representative Astraeus specimens were measured. Surface sections of these structures were cut and examined in Melzer solution and cotton blue to determine the diameter of hyphae and spores extracted from the spore sac, using an optical microscope (Olympus BX51®) with a digital camera (H100H®) and software (Olympus Microscope Screen Saver, Large Version).

Botanical identification of Quercus species

Vegetative structures of five oak trees were collected at each of the three sites, finding sporomes of A. aff. hygrometricus. Specimens were classified and identified according to Zavala-Chávez (2003) and matched with the collections of the Isidro Palacios Herbarium of the Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí, Herbario Nacional de México and Herbario de la Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes.

Physicochemical characterization of the soil

A subsample of soil (0 to 20 cm depth) was taken from each of the oak trees in each cardinal point of the shaded area where sporomes were found, to integrate them into a composite sample, for a total of five samples per site. The soil was analyzed in the Plant Nutrition laboratory of the Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus Montecillo. This analysis included texture, pH, organic matter (OM), carbon percentage (C), carbon-nitrogen ratio (C/N), total nitrogen (TN) and phosphorus (P), according to NOM-021-RECNAT-2000 (Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales [SEMARNAT], 2000). The values of these measurements were subjected to an ANOVA and Tukey comparison of means (P ≤ 0.05) with the InfoStat® software (Di Rienzo et al., 2015).

Results and Discussion

At the three studied sites, A. aff. hygrometricus was associated with Quercus potosina Trel, Q. pringlei Seemen ex Loes, Q. tinkhamii C. H. Muller and Q. striatula Trel. (Table 1). These species were recorded in an altitudinal range from 1 820 to 2 740 m (Table 1), consistent with that reported by Giménez de Azcárate and González (2011) and Sabás et al. (2015). Other studies report the association of A. hygrometricus with Q. petraea (Mattuschka) Liebl., Q. robur L., Q. cerris L., Q. ilex L., Q. serrata Thunb., Q. crispula Blume, Q. suber L., Q. faginea Lam. subsp. broteroi A. Camus, Q. glauca Thunb. and Q. salicina Blume (Barrico et al., 2012; Fangfuk, Petchang, To-annun, Fukuda, & Yamada, 2010; Kayama & Yamanaka, 2014; Torrejón, 2007).

Table 1 Characteristics of oak trees in association with Astraeus aff. hygrometricus, located in the three study areas of the Altiplano Potosino in Mexico.

| Study site | Species | Habitat | Altitude range (m) | Precipitation (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| El Peñón Blanco | Quercus potosina | Shrubby-arboreal | 2 270 - 2 740 | 335 |

| Sierra de Guanamé | Quercus tinkhamii | Shrubby-arboreal | 2 130 - 2 380 | 446 |

| Quercus pringlei | Shrub | |||

| Sierra La Mojonera | Quercus striatula | Shrub | 1 820 - 2 480 | 344 |

In Mexico, A. hygrometricus has been previously reported from oak forests, shrubby oak forests, disturbed oak forests and pine-oak forests, without specifying the Quercus species in these ecosystems (Esqueda et al., 2009; Pardavé et al., 2007; Piña-Páez et al., 2013; Terríquez, Herrera, & Rodríguez, 2017; Torres, Rodríguez, Herrera-Fonseca, & Figueroa-García, 2020). In Chihuahua, these fungi have been associated with Q. striatula in disturbed areas (44.0 to 63.6 % fungal abundance due to logging and burning, respectively), with Q. depressipes Trel. in areas of forest regeneration, and with Q. sideroxyla Humb. & Bonpl. and Q. crassifolia Humb. & Bonpl. in natural forests (Quiñónez et al., 2008).

In the present study, A. aff. hygrometricus was associated with four Quercus species distributed in a semi-arid environment with a mean annual precipitation of 375 mm (range 335 to 446 mm; Table 1). In this regard, it has been shown that mycorrhizal associations with woody plant species facilitate their absorption of water and minerals, due to the fungal absorptive capacity and different morphophysiological and biochemical strategies (Bréda, Huc, Granier, & Dreyer, 2006). This highlights the importance of A. aff. hygrometricus in the ecological survival of Quercus in the Altiplano Potosino. Gehring, Sthultz, Flores-Rentería, and Whipple (2017) pointed out that ECMs with the capacity to improve plant survival and growth, under conditions with water scarcity, will have a great relevance to forest vulnerability due to the warming and drought conditions predicted for the future. However, the development of mycorrhizal synthesis of Astraeus species is necessary to test the biotechnological and ecophysiological potential that this fungal species could have on the survival of the studied oak forests under semi-arid conditions.

Macro and microscopic characterization of Astraeus aff. hygrometricus

Results and comparison with other studies carried out in different climates and, generally, in mixed forests, are shown in Table 2, where it is observed that the morphological characteristics vary depending on the climate according to the geography of the reports. In the study area, the diameter of the endoperidium (13 to 20 mm) was larger than that reported in France (13 to 14 mm). Pérez-Calderón, Botello-Camacho, González-Fernández, and Valero-Galván (2015) indicate that there is an inverse relationship between diameter and amount of rainfall; in this regard, the average annual precipitation was 375 mm in the study area (Phosri, Martín, & Watling, 2013).

The number of laciniae (7 to 10) was found to be in the global range between regions (5 to 14 per basidiomata); likewise, hyphal diameter (4.4 to 9.2 µm) was similar with that reported in Argentina (4.5 to 8 µm) and France (4.5 a 6.5 µm).

Table 2 Comparison of macroscopic and microscopic characteristics of Astraeus aff. hygrometricus in some world regions.

| Macroscopic | Microscopic | Country | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEXP (mm) | DENDP (mm) | Number of laciniae | Spore diameter (µm) | DENDPH (µm) | DEXPH (µm) | |

| 42.3-57.4 | 13-20 | 07-oct | 8-10.1 | 4.4-6.9 | 4.9-9.2 | Mexico (current study) |

| 30-70 | dic-25 | 05-ago | 6.5-11.0 | 05-ago | 4.5 | Argentina (Nouhra & Domínguez, 1998) |

| 20-25 | 13-14 | dic-14 | 10-12.5 | 4.5-6.5 | France (Phosri et al., 2013) | |

| 48.4-58.5 | 15.6-20 | 06-ago | 7.5-9.1 | Mexico (Pérez-Calderón et al., 2015) | ||

DEXP: diameter of exoperidium, DENDP: diameter of endoperidium; DENDPH: diameter of endoperidium hyphae; DEXPH: diameter of exoperidium hyphae.

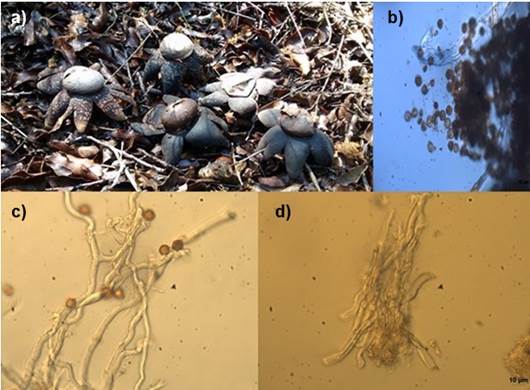

Variations in macroscopic and microscopic characteristics are an indicator of climatic characteristics that directly affect fungal development and plasticity of Astraeus species to thrive in diverse ecosystems. Figure 2 shows some morphological characteristics of A. aff. hygrometricus, analyzed in the present study.

Figure 2 Structures of Astraeus aff. hygrometricus in oak forest relicts of the Altiplano Potosino: (a) sporomes; (b) verrucose globose spores (40x); (c) cylindrical to tortuous hyphae of external exoperidium, septate with y-connections, bifurcate, thick-walled, hyaline (40x); d) smooth, slightly ornamented to sparsely verrucose hyphae of internal exoperidium, cylindrical and thin-walled, with y-connections, sometimes with attenuated apices, hyaline, non-amyloid, with rounded hyphal termination and sparce clamp-connections (40x).

Soil characterization

Table 3 shows the soil characteristics of the sites analyzed. The fungal species A. aff. hygrometricus developed in soils with both clayey and sandy loam texture. In Sonora and other regions of the world, A. hygrometricus has been found in soils with sandy loam and loam texture (Esqueda et al., 2011; Pavithra, Greeshma, Karun, & Sridhar, 2015). The common feature in these studies is the presence of such fungi in soils with a significant proportion of sand.

Table 3 Physical and chemical characteristics of soil where Astraeus aff. hygrometricus grows in association with Quercus in the Altiplano Potosino.

| Characteristics | Study sites | Probability F | CV (%) | LSD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB | SM | SG | ||||

| Texture | Sandy crumb | Clayey crumb | Clayey crumb | |||

| pH | 5.00 a | 7.80 b | 7.70 b | < 0.0001 | 2.78 | 0.32 |

| Organic matter (%) | 39.92 a | 35.04 a | 29.08 a | 0.3427 | 36.75 | 21.24 |

| Carbon (%) | 23.16 a | 18.61 a | 14.99 a | 0.1655 | 33.41 | 10.66 |

| C/N ratio (%) | 11.60 a | 11.60 a | 11.60 a | 0.4914 | 0.03 | 0.005 |

| Total nitrogen (%) | 2.00 a | 1.75 a | 1.39 a | 0.343 | 36.76 | 1.06 |

| P (mg∙kg-1) | 84.97 b | 3.75 a | 0.77 a | 0.0091 | 134.2 | 67.54 |

PB: El Peñón Blanco hill, SG: Guanamé mountain range, SM: La Mojonera mountain range. Characteristics with the same letter are similar between sites according to Tukey's least significant difference (LSD, P = 0.05). CV: coefficient of variation.

The soil of El Peñon Blanco site had the lowest H+ concentration (reported as pH) (P < 0.05). A. hygrometricus showed a wide adaptation to soil pH variation (5.0 to 7.8). This coincides with that reported in the state of Sonora, where these fungi grow in soils with pH from 4.5 to 7.8 (Esqueda et al., 2009, 2011). Tolerance to different pH is the basis for recommending inoculation of A. hygrometricus during oak establishment, both in acidic and calcareous environments (Kayama & Yamanaka, 2014, 2016).

OM, C, C/N and TN values were similar (P > 0.05) for the three sites. The soils were classified as low in TN (1.39-2.0 %). With respect to P, the soils of the Mountain Ranges Guanamé and La Mojonera were classified as low in P (0.77 to 3.75 mg∙kg-1) and only the soil of El Peñon Blanco was classified as high in this nutrient (P < 0.05, 84.97 mg∙kg-1). Arteaga, León, and Amador (2003) reported that the high percentage of OM, composed mostly of oak leaves, is closely related to higher contents of P and other nutrients in the soil. Dieleman, Venter, Ramachandra, Krockenberger, and Bird (2013) indicated that at higher altitudes, colder and wetter conditions prevail, in addition to higher soil acidity, conditions that reduce microbial activity, which is responsible for degradation of forest substrates.

Soil C content was slightly higher (not significant) in El Peñon Blanco (23.16 %); this element, besides being related to the OM content, is also explained by the parent material. This is different between sites: granite in El Peñon Blanco; calcareous shale, siltstone and limestone in Sierra La Mojonera; and limestone-limolite in Sierra de Guanamé. Higher organic C content of soil derived from granite (5.3 kg∙m-2) has been reported compared to that originating from limestone (3.5 kg∙m-2); moreover, the type of parent material has indirect control over soil C dynamics, through its influence on microbiota (Heckman, Welty-Bernard, Rasmussen, & Schwartz, 2009), fertility, soil quality, and environmental impact (Cristóbal-Acevedo, Tinoco-Rueda, Prado-Hernández, & Hernández-Acosta, 2019).

Altitude may be determining the presence of Quercus species; also, the interaction of these with the parental material and environmental factors could influence soil fertility. In this study, Q. potosina (present in El Peñon Blanco with an average altitude of 2 505 m) was associated with higher nutrient and OM contents, while the lowest values were found in the lower altitude sites, where Q. tinkhamii and Q. pringlei (Sierra de Guanamé, 2 225 m) and Q. striatula (Sierra La Mojonera, 2 150 m) grow.

The study of soil conditions where A. aff. hygrometricus grows contributes to the knowledge related to this species, since certain ECM may be adapted to specific niches. This helps to a better use of soil resources (Kranabetter, Durall, & Mackenzie, 2009) by the production of mycelium that can potentially act as an extension of the root system of woody species, which enhances their nutrient and water acquisition efficiency for the host plant (Chalot & Plassard, 2011; Liu, Li, & Kou, 2020) and decreases nutrient losses from the ecosystem (Van Der Heijden & Horton, 2015). The pH is one of the soil characteristics that has a close relationship with the beneficial effect of ECM, since, under acidic conditions, fungal communities will be dominated by taxa that are dependent and efficient in releasing organic P from soil organic matter (Carrino-Kyker et al., 2016). It has been shown that mycorrhizal fungi can increase P availability by the secretion of phosphatases that degrade organic P (Burke, Smemo, & Hewins, 2014). This could explain the high P content in the soil of this study, associated with acid pH.

Conclusions

The ectomycorrhizal fungus Astraeus aff. hygrometricus, associated with four Quercus species (Q. potosina, Q. tinkhamii, Q. pringlei and Q. striatula) was found for the first time in oak forests relicts of the semi-arid Altiplano Potosino at altitudes ranging from 1 820 to 2 740 m. This indicates the ability to establish ectomycorrhizal symbiosis in semiarid environments with low precipitation (375 mm per year) and in soils with acid to basic pH (5.0 to 7.8) with low N and high P levels. The study contributes to strengthen the knowledge related to the macro- and microscopic morphological characteristics of A. aff. hygrometricus (which may vary depending on the study site), its plasticity to thrive in diverse ecosystems, and the importance and survival of Quercus and Astraeus in vulnerable environments.

text in

text in