Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

Share

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

Print version ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.7 spe 15 Texcoco Jun./Aug. 2016

Articles

Using business plans for the relationship between the market and producers of high and very high marginalization

1Campo Experimental Centro de Chiapas-INIFAP. Carretera Ocozocoautla-Cintalapa km 3, Ocozocoautla de Espinosa, Chiapas, México. (salinas.eileen@inifap.gob.mx).

2Campo Experimental Valles Centrales de Oaxaca-INIFAP. Calle Melchor Ocampo No. 7, 68200, Santo Domingo Barrio Bajo, Etla, Oaxaca, México.

3Centro de Investigaciones Económicas, Sociales y Tecnológicas de la Agroindustria y la Agricultura Mundial (CIESTAAM)-Universidad Autónoma Chapingo, Texcoco, México. (redes.rendon@gmail.com).

The poverty is a characteristic of most of the families living in rural areas, farmers dependent on agricultural production as one of the main activities. These activities have low productivity, among others, by low technological level and it’s predominantly subsistence orientation. Therefore, monetary income is very limited and not enough to cover their consumption needs. The main challenge is to promote the competitiveness of rural families in this condition, through greater ties to the global economy. This research proposal aims to generate an operating methodological model to achieve competitiveness of small farmers in poverty and marginalization. The project was developed in the municipality of Ocotepec, considered Within National Crusade against Hunger, in Chiapas state; was divided into two stages, stage one, it refers to the identification of the factors limiting rural competitiveness and determination of portfolio of business opportunities in the conditions of marginalization and poverty; stage two involves the design of the Business Plans. It is concluded that economic identifying with a business plan activities represent an alternative to improve the economic conditions of the producers.

Keywords: business plan poverty; competitiveness; marginalization; market

La pobreza es una característica de la mayor parte de las familias que viven en el medio rural, los campesinos dependen de la producción agropecuaria como una de las principales actividades. Estas actividades presentan una baja productividad, entre otras, por su escaso nivel tecnológico y su predominante orientación al autoconsumo. Por consiguiente, su ingreso monetario es muy limitado y no les alcanza para cubrir sus necesidades de consumo. El principal reto consiste en propiciar la competitividad de las familias campesinas en esta condición, mediante una mayor vinculación a la economía global. La presente propuesta de investigación pretende como objetivo generar un modelo metodológico operativo para lograr la competitividad de los pequeños agricultores en condición de pobreza y marginación. El proyecto se desarrolló en el municipio de Ocotepec, considerado dentro de la Cruzada Nacional contra el Hambre, en el estado Chiapas; se dividió en dos etapas, la etapa uno, se refiere a la identificación de los factores que limitan la competitividad rural y determinación del portafolio de oportunidades de negocio en las condiciones de marginación y pobreza; la etapa dos consiste en el diseño de los Planes de Negocios. Se concluye que la identificación de actividades económicas con un plan de negocios, representan una alternativa para la mejora de las condiciones económicas de los productores.

Palabras clave: competitividad; marginación; mercado; plan de negocios pobreza

Introduction

One of the most important for the development of a territory factors is the presence of companies, the question is how do companies develop in rural areas? Some mechanisms are the establishment of industries, the creation of parks or industrial areas or simply by the fact of making a road (Figueroa et al., 2012). The roads are an important part for rural producers can be linked to the market more easily by having access or faster and accessible exits.

Traditionally rural development has lacked an entrepreneurial approach, so it requires a focus on market demand. To convert the rural producer, regardless of size or socioeconomic status, a profitable and competitive company, it requires a business plan that incorporates a minimum of capital and adequate and timely funding (Cadena et al., 2013; Rodríguez et al., 2013). Factors favoring improvements are referred to innovation fostered through productive interaction through relationships that explain communication flows as the process of adoption and adaptation (Rendon et al., 2013; Ayala, 2014).

Competitiveness is the ability of companies to compete in the markets and, based on its success, gain market share, increase profits and grow (Berumen et al., 2009). However, Del Canto Fresno (2000), indicates different types of competitiveness, emphasizing the "territorial competitiveness" which has four dimensions: social, environmental, economic environment and positioning in the global context. Canzanelli (2004) clearly indicated that changes between being a peasant to be an entrepreneur, whether individually or in a form of a cooperative between farmers tend to be gradual. From the point of view of classical economics where everything that can be linked to the market this necessarily meant to achieve gains in marginalized areas not everything should be privileged in the optical market, not in the early stages, but if the subsequent stages when the organization begins to mature and productive projections are geared for the market.

Using the methodology of policy analysis matrix (MAP), a study called analysis was performed without the project, establishing the guidelines for determining the level of competitiveness by the competitiveness index or ratio (RCR). Subsequently a new analysis called study project was established, since it intervened in households and producers through capacity building, technology transfer and training to achieve innovation, not without first going through the adoption and its impact in the production units and to bring them to the idea of business plans, with a view to the best choice of selling their commodities. About Cadena et al. (2009); Ayala et al. (2014) indicated that the adoption of technology is not always the result of a transfer process often is a phenomenon that depends on observation, intelligence, determination and the risk of the producers themselves.

Once established the levels of competitiveness of producers and detecting potential products to destine the market and increase the income level in order to improve the standard of living of producers, a business plan in the cultivation of avocado was established (Persea americana L.), hoping that the relationship was closer to the market.

The main objective of this study was in the first instance to analyze the situation of production in the municipality of Ocotepec, Chiapas, in order to establish the level of competitiveness, as measured by the household, analyzing the information gathered through a survey of all assets and livelihoods of producers.

Materials and methods

The study on competitiveness was held in the municipality of Ocotepec; the head of the municipality of Ocotepec is located at 17o 13' 27" north latitude and to 93o 09' 47" west longitude, at a height above sea level of 1 800 m. The municipality of Ocotepec has a land area of 62 km2. Ocotepec, bordered on the north by the municipality of Chapultenango, east to the town of Tapalapa, south with the municipality of Coapilla, southwest with the municipality of Copainala, east to the town of Francisco Leon.

To analyze the methodology called competitiveness policy analysis matrix (MAP) which is primarily based on budget analysis, at market prices and social prices (opportunity costs) was used. Thus, competitiveness is determined (measured as the private return) and comparative advantages (efficient use of domestic resources in production) of various production systems and different production areas (Naylor et al., 2005). This method has as its main objective, measuring the impact of government policies and market distortions on private profitability and efficiency in the use of resources (Rebollar et al., 2009).

Competitiveness is determined and measured by the competitive relationship (RCR) (Escobar et al., 1999); for this, the coefficient factor cost (C) and the value added to private prices, as shown in Equation 1 is determined.

Where: RCP= ratio of private cost; C= cost of domestic factors; A-B= added value stated at private prices.

RCP take values between 0 and 1; 0> RCR <1 If the value is closer to 0 means it is more competitive, if one tends to mean the opposite.

A business plan taking into account the existing secondary information system for product avocado (Persea americana L.) and these Hass was performed. This fruit was chosen by the producers, introducing greater opportunities to market and is the most demand is in the portfolio of opportunities conducted to determine which product was feasible to market faster.

Results and discussion

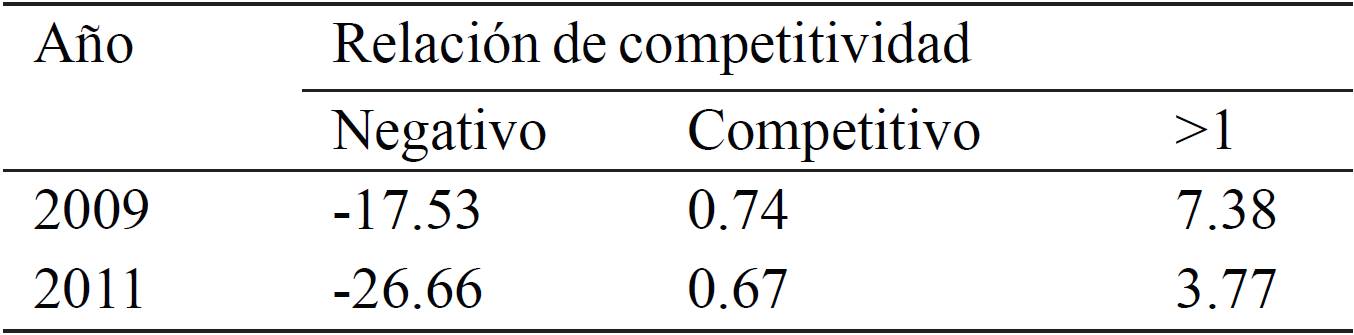

The competitive relationship indicates whether households are competitive or not, depending on the value obtained (Cadena et al., 2013). In the case of an initial diagnosis Ocotepec where 120 surveys were conducted, taking data from each production activities and obtaining indicators as the ratio of private or RCP cost, through the MAP it was established in 2009.According to the results obtained in three strata defined negative, competitive and older established one. Following this same analysis for 2011 the same strata are established, in order to make a proper comparison in the two years of study and establish the dimensions that were reached as to the overall objectives of the project (Table 1).

The units are within the negative indicator in 2009 refer to a relationship competitiveness -17.53 and according to the definition of this indicator RCP does not take a value between zero and one, therefore are not competitive; and it could be established that households that are within this stratum are not only non-competitive, but also do not have robust mechanisms in its production structure that allow link in the market, which refers to are those subsistence farmers who not only production but consumption is in need of any other income or financial support for their survival.

Within the stratum greater than one, it establishes that these likewise has no relevance in their production to market linked and may be found in the same situation as negative; i.e., its dynamic life tends to consumption and to establish mechanisms in their livelihoods through support or benefits in the form of help or support from government or non- governmental institutions.

The difference lies in the value added in the negative layer is less than cost, i.e. the value of production does not cover the total costs what it does establish itself as a loss. In values greater than one, the value of production can cover total costs, but a minimum gain is obtained; so when calculating the RCP exceed the nominator and the denominator tends to be greater than one. However, this indicates that there is little connection to the market perhaps because production is mostly self-consumption and sales are minimal. Given this situation everything indicates that these producers fall into the conceptualization classical regarded as peasants Chayanov (1974), Wolf (1975) and later retaken by Martinez (1987); Galesky (1997); Palerm (2008); Jurado and Bartra (2012), who describe comprehensive and thoroughly.

As for production units located within the stratum competitive, the competitiveness index is 0.74; i.e. these production units that can show the link with the market and also to solve their consumption, spend a significant part of their production to the market, therefore are profitable units. For 2011 and after surgery to improve their production processes, a new analysis of competitiveness called "with project" was established. The results were set up in three layers, wherein:

The negative layer shows a tendency to be more negative (-26.66), not necessarily to be more dependent on other factors outside their production, but more the lack of market linkages. This leads to establish stronger mechanisms to lead them to not only be self-consumption, if not other sales of their products. The layer of greater than one shows a decrease in terms of CRP significant indicator since the year 2011 is 3.77; so you would expect that some production units could have gone from being greater than one to be competitive or with the intervention and implementation of new technologies increase the value of production and lower costs, which make the trend toward competitiveness. The layer termed as competitive shows a decrease in the indicator obtained in the base year, being 0.67; indicating that the units within this stratum, in establishing the technologies in their production processes, could be better linkage in the market.

Overall, the change in the competitiveness index, the start of the intervention at the end of it, reflecting a decrease of 31.4% overall. However, there are some factors that can affect the competitiveness of a product, which could be, productivity, production costs, international prices and the relative location of the production areas to consumer centers (García et al., 2006). To reduce the effect of these factors must be established support mechanisms for producers to have access to the market level, and through business plans for the improvement of production processes and competitiveness of producers.

Business plans. The establishment of competitiveness indices allowed, besides knowing the situation of production units analyzed to establish the necessary guidelines to link potential products through business plans; resulting in a study to Hass avocados. It should be considered that to be competitive must be differentiating factors achieve in a friendly environment to environment and improvement in social conditions, added values established advantages over the product obtained above others (Corredor, 2015) generated . As traditional crops of corn (Zea mays L); bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L. and Phaseolus coccineus L.) and cassava tubers especially (Manihot esculenta Krantz), are produced mainly for the support of families; that is, as a complement to the daily diet and in the form of savings in their consumption expenditures. Among these products corn is the most remarkable product because it is grown in greater percentage of the surface that have the producers and which is given a constant process of production so that the yields are high and can sustain his family at one time considered.

Avocado this product is new in the region, established six years ago. Its establishment has been supported by several institutions in a system corn intercropped with fruit trees (MIAF) plantation system widely described by Cortes et al. (2005a and 2005b) and Cortes et al. (2010); Turrent et al. (2014). Within the business plan for avocado under MIAF system, a component of commercial viability, where is incorporated the analysis of demand, supply and contrast, as well as the proposed sale price and the marketing channel (Peña et al., 2015).

Productive chain

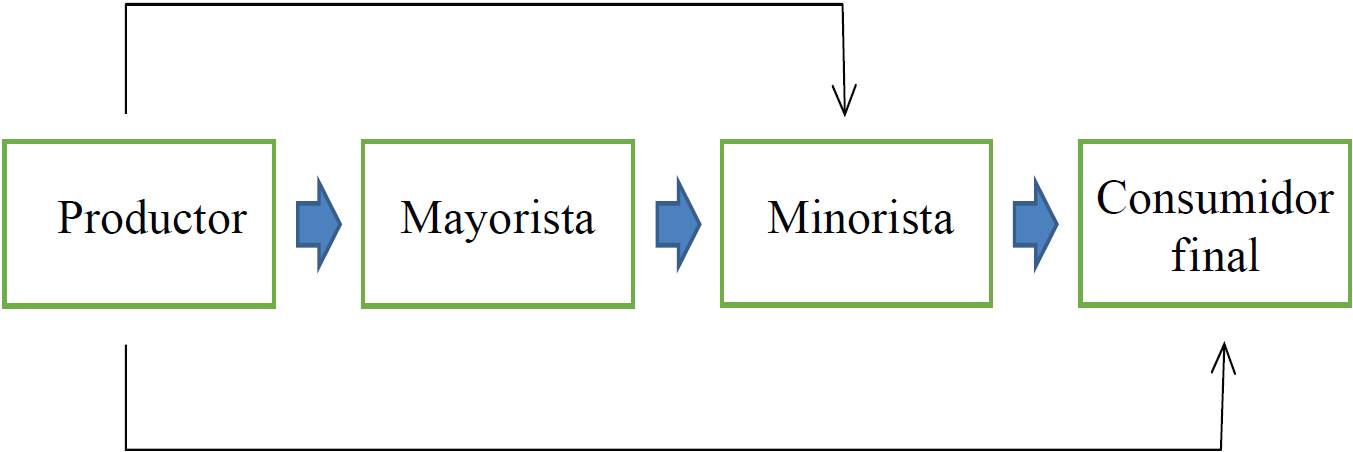

Hass avocado is defined as a product sold fresh, marketed throughout the year; the producer, wholesaler, retailer and end consumer, for the state of Chiapas 4 main production chain links are established. Producers or suppliers are located in the states of Puebla, Chiapas, mainly, besides the state of Michoacan; where the latter also become wholesalers distributing its production to retailor end-consumers (Figure 1).

The supply route is done either producer to wholesalers located mainly in the central supply of Tuxtla Gutierrez, who distributes to local markets and shops in the region, subsequently to the final consumer. There is another supply route that goes from producer to retailer or merchant markets located in the region or stores of various products and finally the last route is the producer or winery to the consumer. End consumers focus on the inhabitants of the region and restaurants.

Wholesalers and retailers. The avocado market in the state of Chiapas, according to data obtained from wholesalers, is that throughout the year there is supply: avocado comes mainly from the states of Puebla and Michoacan. The fresh avocado is distributed in plastic boxes commonly 10 kg of extra fourth grade.

The wholesalers are located in the central supply of Tuxtla Gutierrez, each has a warehouse where they sell not only the fruit, but other products such as onions, peppers Capsicum spp., Potato Solanum tuberosum, pumpkins Cucurbita spp., Jicama Pachyrhizus erosus, among other. Some have, important for conservation of products for sale and maturity of some of these such as avocado cold rooms. There are differences between wholesalers, one of which is that sold more than one product are hoarders, i.e. buy the product directly from producers or distributors of avocado. This type of wholesale collect avocado from the state of Puebla primarily arguing that it is a quality product that meets the standards required by the market, mainly in the process of maturity. Because as the fruit is cut at a stage where it is not yet mature, at the time of stored have to have a low temperature that allows the avocado ripen properly and when cut has a green color yellow that the consumer looks rather gray tones ref lecting unfit for consumption.

The other wholesalers, are from the state of Michoacan. These are producers who have the ability to shift production and introduce the state of Chiapas. These wholesale market two levels; distributing to other wholesalers, retailers and end customer markets. They have cold chamber so that the product reaches its maturity suitable for the market. Product marketing for the two types of wholesalers is according to the characterization of the CODEX standard for avocado (CODEX STAN 197-1995).

End customers. End consumers are those people where the final product arrives fresh; the main features you are looking for the consumer is that of a ripe fruit, green with yellow tones, with pleasant taste, the flesh should be firm and mainly not present oxidation. The importance of the avocado is a product that can be obtained throughout the year is very valuation of final consumers. However, because in some months of the year the price of Hass avocado goes up, that makes consumers not included in the daily diet, and prefer the use of landraces that usually found in the market at cheaper price. Another important feature for end users is that of the benefits obtained from consuming avocado, because the whole family can consume, and is rich in unsaturated fats.

Market situation regarding the situation of producers. The producers San Pablo Huacano, in the municipality of Ocotepec, Chiapas, have a yield per hectare of 6 t ha-1 on average Hass avocado. Currently it has a weak market because the market only in the village or on roadsides and do not have a buyer who can integrate the entire product, coupled with the lack of a marketing strategy that allows sell their produce at local markets. The avocado producers which account St. Paul Huacanó is the Hass variety, and according to the classification CODEX STAN 197-1995, is classified into first and until the 4th grade. The main disadvantage would producers is the lack of infrastructure for avocado reach the maturity required in the market, which is one of the main guidelines calling for wholesalers to purchase, because the distribution of wholesale retailers is necessary that the fruit is not fully ripe, due to handling, but if such a point to guarantee their maturity to the final consumer.

Positioning of production. The producer organization is composed of 12 members, not currently have a legal constitution, but if a working group that has allowed them to work and get some support as obtaining avocado and advice from experts in plant breeding and production of this fruit, and improve their production system corn and beans. They have been able to obtain training in subjects such as management and accounting, as well as other technical trainings. Avocado growers of San Pablo Huacanó are convinced that it is necessary to have a company capable of solving inclement market. It is of interest to the legally constituted an association and thereby ensure the level of product on the market to supply the market in the short, medium and long term according to the market requirement, first ensuring product quality, but also ensure availability in the level of production to meet demand from its trading partners.

Size of the target market. The target market is planned in the short, medium and long term, which involves establishing strategies to supply the type of market you want to reach. In the short term it has established to sell retail in the municipalities of Copainala and Tepactan, where according to the INEGI (2010), in Copainala there are 5 240 households and 21 050 people, equivalent to the consumption of at least 168 -estimated as avocado annual per capita consumption in Mexico annually-tons of avocado. In Tepactán they will have registered 9 582 households with a total of 41 045 people, having a market to supply a demand for up to 328 tons.

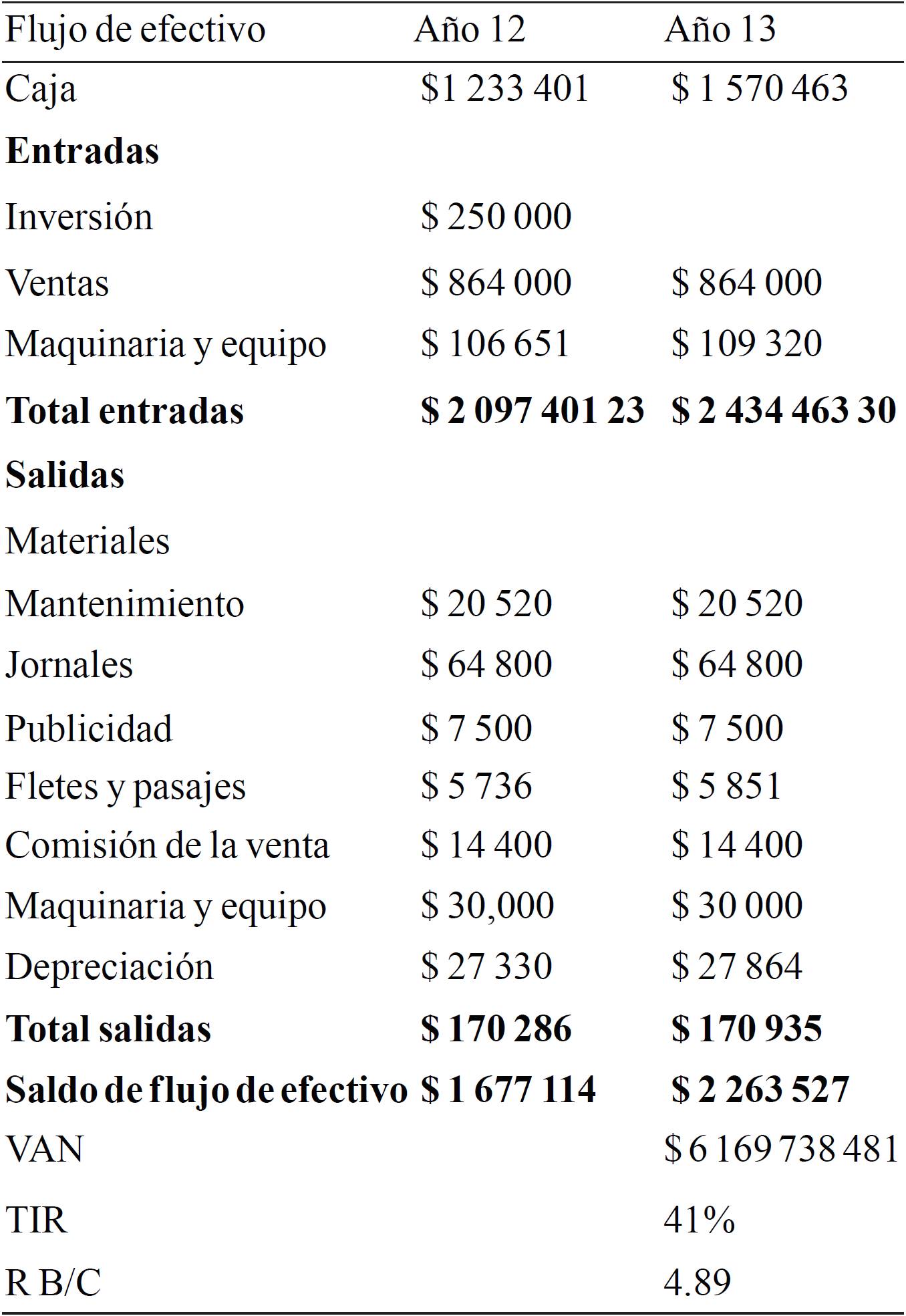

Financial analysis. For economic and financial analysis is based on the methodology of project evaluation, where each of the indicators are valued concepts that express the economic performance of the investment company, which indicated profitability, and comparison and selection between different investment alternatives (Franco et al., 2014).

Costs are set not only on the production side, also take into account additional costs, such as advertising, transportation, purchase of machinery and equipment. The higher costs are the wages and there are no gains over the first four years because of the initial investment and the lack of sales. However in year five earnings are $44 505.41 for selling weight total production. For the year 7 to 11 new plantings of Hass avocado with MIAF system are established, these plantations correspond to 300 new plants producing equivalent to a total of 3 600 plants by the total. For a seven year investment takes $168 120 pesos for plantations, however, as there are sales, producer support to cover the costs of new investment.

The expenses are recorded in this cash f low are: advertising and sales commission. Maintenance is according to the activities performed as pruning and fertilization, among others. Within the cash flow in year 8 is expected to have a deficit in housing, however the final balance is positive. For years 12 onwards, it is expected that production will stabilize the 400 plants that have at producer, plus it is to make a new investment in the construction of a cold room, to have a product in accordance with the requirements the long-term market. This cold room, will cost $250 000; and your investment is planned for the 12th year of production.

Table 2. Cash flow from the producer organization Hass Avocado, San Pablo Huacanó, Ocotepec, Chiapas, years 1 to 6.

It is established that producers can afford this expense and for the year 13 agreements with wholesalers for more sales are made. In the latter period increased advertising costs and sales commissions in the amount of volume handled and distributed. In the long term also it intends to purchase vehicles and infrastructure.

In the medium and long term market Tuxtla Gutierrez, the municipality has 43 886 households with a total of 553 374 inhabitants, which could take up to about 4 427 tons of avocado would be added. While the data show that it is very profitable avocado cultivation in the town of Ocotepec, Chiapas, it is also true that the factors affecting take a company like this. Something similar is found Rodríguez et al. (2015) to study the production of red tomato, Lycopersicon esculentum L. in a marginalized municipality of Oaxaca, finding an inverse relationship between the level of sales and competitiveness index. That is, if the sales rate increases, the rate decreases, which means that the production units are more competitive and conversely if sales decline rate increases competitiveness and FPU are then less competitive. If sales increase by 30% would improve competitiveness by 28% with respect to the current situation.

Table 3. Cash flow from the producer organization Hass Avocado, San Pablo Huacano, Ocotepec, Chiapas, year 7 to 11.

Conclusions

With the data presented and the expectations of producers and the growth of its plantations in the village of San Pablo Huacanó, Ocotepec, Chiapas, with producers of Hass avocado is possible to make a good agribusinesses in areas of high and very high marginalization, since in the medium and long term production of avocado can generate more profits to producers who follow only planting their satisfactions. Awareness of them to have a permanent technical advisor to have the quality demanded by the market is identified as necessary.

Future research could contribute to possible resistance by producers in developing business plans.

Literatura citada

Ayala-Sánchez, A. 2014. Unidades de transferencia de tecnología para la innovación agropecuaria y forestal del INIFAP. In: Congreso Internacional de Investigación e Innovación 2014 Multidisciplinario. Centro de Estudios Cortázar. Universidad de Guanajuato. Cortázar, Guanajuato, México. 35 p. [ Links ]

Ayala-Sánchez, A.; Cadena-Iñiguez, P.; Zambada-Martínez, A.; Pérez- Guel, R.; Güemes-Guillén, M. J.; Morales-Guerra, M.; Rodríguez-Hernández, R. F. y Berdugo-Rejón, J. G. 2014. Niveles de relación interinstitucional dentro de la cadena agroindustrial del aguacate en Morelos. Vinculación para la transferencia y la innovación tecnológicas. Gobernanza de ciencia, tecnología e innovación. Díaz, C, M. de los Á. (coord.). Laboratorio transdisciplinario de investigación más desarrollo; Cuerpo académico consolidado UV- CA-311. REDESCCYTT. Redes para el desarrollo, cultura, ciencia y tecnología en transdisciplinariedad. Universidad Veracruzana, Veracruz. 218-238 pp. [ Links ]

Beruman, A. S. y Palacios, S. O. 2009. Competitividad, clúster e innovación. Editoriales trillas. México. 1-103 pp. [ Links ]

Cadena-Iñiguez, P.; Morales-Guerra, M.; González-Camarillo, M.; Berdugo-Rejón, J. G. y Ayala-Sánchez, A. 2009. Estrategias de transferencia de tecnología, como herramientas del desarrollo rural. INIFAP. CIRPAS. Campo Experimental Centro de Chiapas. Chiapas. Libro técnico No. 2. 94 p. [ Links ]

Cadena, I. P.; Rodríguez, H. R.; Zambada, M. A.; Berdugo, R. J. G.; Góngora, G. S.; Salinas, C. E.; Morales, G. M. y Ayala, S. A. 2013. Modelo de gestión de la innovación para el desarrollo económico y social en áreas marginadas del sur sureste de México. Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales Agrícolas y Pecuarias, centro de Investigación Regional Pacífico Sur- Campo Experimental Centro de Chiapas. Libro Técnico No. 10. Ocozocoautla de Espinosa, Chiapas, México. 120 p. [ Links ]

Canzanelli, G. 2004. Valorización del potencial endógeno, competitividad territorial y lucha contra la pobreza. Center for International and Regional Cooperation for Local Economies. Paper No. 1. 20-30 pp. [ Links ]

Corredor, L. R. 2015. La competitividad en las pymes y la cooperación internacional: una experiencia desde Colombia. Divergencia. (19):116-129. [ Links ]

Del Canto Fresno, C. 2000. Nuevos conceptos y nuevos indicadores de competitividad territorial para las áreas rurales. Anales de Geografía de la Universidad Complutense. 20:69-84. [ Links ]

Chayanov, A. 1974. La Organización de la Unidad Doméstica Campesina. Ediciones Nueva Visión. Buenos Aires, Argentina. Ediciones Nueva Visión. En: Figueroa-Manuel, V. 2005. América Latina; descomposición y persistencia de lo campesino. Revista Latinoamericana de Economía. Vol. 36 N° 142 julio-septiembre 2005. 27-50 pp. [ Links ]

Figueroa, V. 2005. América Latina; descomposición y persistencia de lo campesino. Revista Latinoamericana de Economía. 36 (142):27-50. [ Links ]

Cortés-Flores, J. I.; Turrent-Fernández, A.; P-Díaz, V.; Hernández-R.; Mendoza-R y Aceves-Everardo, R. 2005. Manual para el establecimiento y manejo del sistema Milpa Intercalada Árboles Frutales (MIAF). Colegio de Postgraduados, Montecillo, Estado de México. 27 p. [ Links ]

Cortés-Flores, J. I.; Turrent-Fernández, A.; Díaz, P.; Jiménez-Sánchez, L.; Hernández E. and Mendoza, R. 2005. Hillside Agriculture and Food Security in México: Advances in the sustainable Hillside Management Project. In. Climate Change and Global Food Security. Lal R.; Stewart, B.; Uphoff, N. and Hansen, D. (eds.). CRC Taylor and Francis. Boca Raton, FL., USA. 569-588 pp. [ Links ]

Cortés-Flores, J. I.; Torres, J. P.; Turrent-Fernández, A.; Hernández, R. E.; Ramos-Sánchez, A. y Jiménez-Sánchez, L. 2010. Manual actualizado para el establecimiento y manejo del sistema Milpa Intercalada con Árboles Frutales (MIAF) en Laderas. Colegio de Postgraduados. México. 30 p. [ Links ]

Escobar-Cruz, G. y Godínez, L. 1999. Evaluación de políticas de competitividad internacional de la producción de jugo concentrado de naranja en el estado de San Luis Potosí. Tesis de licenciatura. Economía Agrícola, Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Chapingo, México. 88-103 pp. [ Links ]

Franco-Malvaíz, A. L.; Bobadilla-Soto, E. E. y Rebollar-Rebollar, S. 2014. Viabilidad económica y financiera de una microempresa de miel de aguamiel en Michoacán, México. Revista Mexicana de Agronegocios. 17(35):957-968. [ Links ]

Figueroa, R. K. A.; Figueroa, S. B. y Figueroa, R. O. L. 2012. De las cadenas productivas a las cadenas de valor: su diagnóstico y reingeniería. Colegio de Posgraduados. México. 76 p. [ Links ]

Galeski, Boguslaw. 1997. Sociología del Campesinado. Editorial Península. Barcelona, España. 133-162 pp. [ Links ]

García-Salazar, J. A.; Rebollar-Rebollar, S. y Rodríguez-Licea, G. 2006. Competitividad, cupos de importación y comercialización de maíz en Sinaloa. Ciencia Ergo Sum. 13 (1): 57-67. [ Links ]

INEGI. 2010. Censo de población de vivienda en el estado de Chiapas. Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geográfica e Informática. http://www.inegi.gob.mx. [ Links ]

Jurado-Celis, S. y Bartra-Verjés, A. 2012. Cómo Sobrevivir al mercado, sin dejar de ser campesino; el caso de los pequeños productores de café en México. Veredas: Revista del pensamiento Sociológico. 2(13):181-191. [ Links ]

Martínez-Saldaña, T. 1987. Campesinado y Política: movimientos o movilizaciones campesinos. In: La Heterodoxia Recuperada en torno a Ángel Palerm. Glantz, S. (comp). Fondo de Cultura Económica. México. 3-31 pp. [ Links ]

Naylor-Lee, Rosamond y Carl-Gotsch, H. 2005. Desarrollo de la capacidad técnica para la evaluación de la competitividad de los productos agropecuarios y los efectos de la apertura comercial. FAO-SEPSA. San José de Costa Rica. 30 p. [ Links ]

Palerm-Ángel. 2008. Los estudios campesinos: orígenes y transformaciones. In: Antropología y marxismo. Palerm, A. (ed). Universidad Iberoamericana. México. 225-254 pp. [ Links ]

Peña-Urquiza, L. S.; Rebollar-Rebollar, S.; Callejas-Juárez, N.; Hernández Martínez, J. y Gómez- Tenorio, G. 2015. Análisis de viabilidad económica para la producción comercial de aguacate Hass. Revista Mexicana de Agronegocios. 19 (36): 1325-1338. [ Links ]

Rebollar-Rebollar, S.; Hernández-Martínez, J. y González-Razo, F. J. 2009. Rentabilidad y competitividad del cultivo del durazno (Prunus Pérsica) en el suroeste del Estado de México. Revista Panorama Administrativo. 4(7): 27-38. [ Links ]

Rendón-Medel, R. y Aguilar-Ávila, J. 2013. Gestión de redes de innovación en zonas rurales marginadas. Centro de Investigaciones Económicas, Sociales y Tecnológicas de la Agroindustria y la Agricultura Mundial (CIESTAAM).Chapingo, México. 175 p. [ Links ]

Rodríguez-Hernández, R. F.; Cadena-Iñiguez, P.; Morales-Guerra, M.; Jácome-Maldonado, S.; Góngora-González, S.; Bravo- Mosqueda, E. y Contreras-Hinojosa, J. R. 2013. Competitividad de las unidades de producción rural en Santo Domingo Teojomulco y San Jacinto Tlacotepec, sierra sur, Oaxaca, México. Agricultura, Sociedad y Desarrollo. 10 (1):111-126. [ Links ]

Rodríguez-Hernández, R. F.; Bravo-Mosqueda, E.; López-López, P. and Cadena-Iñiguez, P. 2015. Impact of sales on the competitiveness of marginalized families, the case of tomato producers from Taviche, Oaxaca, Mexico. Global Advanced Research Journal of Agricultural Science. 4(7):325-332. [ Links ]

Turrent-Fernández, A.; Espinosa-Calderón, A.; Cortés-Flores, J. I. y Mejía-Andrade, H. 2014. Análisis de la estrategia MasAgro- Maíz. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. 5 (8):1531- 1547. [ Links ]

Wolf, E. 1975. Los campesinos. Editorial Labor. Barcelona, España. 150 p. [ Links ]

Received: February 2016; Accepted: April 2016

text in

text in