Introduction

In the recent scientific literature about Mexican migration, we can find cutting-edge research on labor migration. However, most of it deals with the issue using approaches that emphasize experiences of poverty, abuse, vulnerability, and precarious conditions among Mexicans in the United States. In this article, I want to underline the fact that Mexican labor migration spans much broader experiences and that the studies about Mexican labor migration could benefit from different perspectives in terms of profiles, experiences, and destinations. In order to do that, what follows is an analysis of the experiences of the Mexican creative class's integration into Canada's labor market.

The studies of the insertion into the labor market of skilled migrants include the notion that large discrepancies exist between the work goals and the occupational achievements of this kind of migrants. In Canada, a country with a strong orientation toward attracting human resources, we find that six out of every ten qualified immigrants will not get jobs in their areas of interest, much less posts similar to those they held in their countries of origin (Kelly, Park, and Lepper, 2011). Among the explanations for this are structural factors like an inefficient system for recognizing and validating foreign degrees and credentials, migratory policies that do not fit the destination country's economic and social needs, and insufficient correlation between immigration policy, economic policy and the demographics of receiving countries. However, when you ask a migrant looking for work in Toronto, he/she would also say that the difficulties involve something called "the Canadian experience."

With regard to migrants' integration into the labor market, the Canadian experience is one of the storylines that comes up most often in Toronto. From everything written and discussed regarding the Canadian experience, we conclude that it is an important barrier for entering and progressing in the labor market. This article's aim is to show what the discourse of the Canadian experience is and how it influences labor integration from the point of view of the subjectivity of qualified Mexican migrants. I propose that the Canadian experience reveals non-institutionalized practices of marginalization in labor market access in Toronto that are produced and reproduced by migrants as part of a discourse of "there's no racism in Canada."

In the next section, the reader will find a discussion about the theory and application of the concepts of creative class and the Canadian experience in the study of skilled migration, as well as background about Toronto's labor market. The second section presents the methodological design of my research. The third section shows and discusses my findings. I finalize the article with reflections about the implications of barriers to migrants' labor market insertion like the Canadian experience in policy and strategy design for labor migration.

Theoretical Framework

The Creative Class

In attempting to capture the great diversity of migrants' profiles and migratory experiences involved in the whole migratory phenomenon, we find descriptions like "middle class," "privileged," "professionals," "qualified," and "cosmocrats" to refer to a certain kind of migrant. These are the people whose migratory experience and individual characteristics place them in between the extreme of complete vulnerability (undocumented migrants, for example) and complete privilege (such as big investors and expatriates). The mobility patterns of the kind of migrants that these categories seek to identify oscillate between travel for pleasure, study, work, or volunteering and a kind of exotic trip for personal change with cosmopolitan, romantic aspects (Amir, 2007:6). Their migratory experiences often shift between these activities and migratory status. They are, for example, those of the tourist who became an international student working part-time at the university and, who, when he/she finishes his/her studies, marries someone from Canada and stays to reside permanently.

In my research, I found that the concept of "creative class" was very useful to achieve what Fernández (2011) calls reconstituting the conceptual mass that we use to characterize and analyze the social phenomena of post-modernity. I think, then, that this concept allows us to compose the approaches utilized to study this kind of migrant and migratory experience. Very particularly, it helps identify a kind of Mexican migration that has been studied very little until now.

The concept of creative class emanates from the theory of creative capital developed by Florida (2003, 2005). This theory accentuates creativity as a fundamental, intrinsic characteristic of being human and a key element in regional economic development. For that reason, it emphasizes the relationship between creative capital, human resource mobility, and economic development. According to Florida, the creative class moves toward "creative centers" that bring together creative capital in the form of technology, talent, and tolerance. He defines tolerance as openness, inclusiveness, and diversity with regard to all ethnicities and lifestyles; talent as a percentage of the population with university educations or higher; and technology as a function of innovation and the concentration of cutting-edge technology. All together, these elements offer functional, tolerant, specialized social and work spaces with educated, creative people (Florida, 2003:10). This mobility dynamic means that producers and seekers of creative capital leave traditional, corporatist communities with working class sectors, to go to these creative centers. This contributes to the emergence of new migratory trends and a "new economic geography" (Florida, 2003:9).

Florida describes a creative class as individuals who have the "luck" to be paid for using their creativity to produce new forms or designs that are useful and transferable through their manufacture, use, reproduction, and commercialization. Florida divides the creative class into two groups: a central group of "super creative" people that includes scientists, engineers, researchers, artists, writers, iconoclasts, and opinion leaders; and a second peripheral group of "creative professionals," whose job activities involve constantly generating creative ways to solve problems. This group spans a great variety of jobs in the technology, financial, business management, legal services, and health sectors. As we can see, the traditional parameters that have characterized skilled migration (formal academic education) only cover one aspect of the creative class.

In migration studies, the concept of creative class has been used in research about regional development to measure the importance of talent and creativity for economic development and competitiveness in post-industrial regions with important knowledge and technology sectors (Houston et al., 2008; Petrov, 2008; Clifton, 2008; Boschma and Fritsch, 2009; Rich, 2012). In these studies, the creative class is represented by individuals with high educational levels and/or professions in sectors considered creative, like the sciences, the arts, and technology; in other words, individuals whose incomes are derived from transforming creativity into economic earnings and new forms of relations of production and socialization. These studies introduce other concepts such as the quality of the place, measured as the capability of a region or city to attract creative capital form outside, to deal with the "pull and push" arguments in which the characteristics of a city in terms of economic growth and competitiveness, exclusivity, and tolerance in the social, cultural, and political spheres, technological innovation, and the presence of a highly educated workforce attracts the creative class, which in turn fosters these same characteristics.

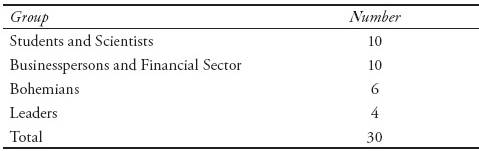

In my research, I have left to one side these discussions to focus on the usefulness of the concept of creative class for studying the flows of skilled migration. As a theoretical input, the concept of creative class allows us to identify and explain a kind of skilled migration that has been little studied until now since it involves two conceptual elements that permit us to overcome the limitations of studying skilled migration based on the years of formal education. One of these elements is economic status or job activity, which defines class, and the second is human creativity, which defines creative (Petrov, 2008:164). To apply it, I have used Petrov's 2008 work about domestic migration in Canada, which offers a more detailed characterization of creative class. In his research, Petrov emphasized the idea that the creative class must be understood in terms of a kind of qualitative capital that surpasses traditional representations of the highly qualified workforce (Petrov, 2008:164). Thus, he broadened the membership of his creative class to include individuals with characteristics, knowledge, and skills not necessarily acquired through formal education. I share Petrov's opinion of the need to broaden what we understand by skilled migration. I believe that by concentrating on formal education and professionals in the technology and science sector, the studies on talented individuals have failed to capture the diversity that characterizes today's labor migration. Petrov's broadened creative class includes four groups: scientists, businesspersons, leaders, and bohemians. I adjusted Petrov's groups to reflect the reality of the Mexican migrant community in Toronto by expanding them to include students and professionals in the financial sector, groups highly represented among Mexican migrants to Toronto. Based on their job activities, I classified my informants into four groups, as shown in the following table:

Multiculturalism and the Labor Market in Toronto

In 1971, Canada became the world's first country to officially adopt a legislative framework to promote and protect its population's diversity. The tradition of defending ethnic and cultural diversity stems from the British and French commitment to mutually respect their languages and religious and civic institutions. This is why Canada's multiculturalist model is built around the interests of the English and the French and their descendants; it is a heterogeneous, urban model made up of immigrants with little connection to rural, white, European Canada; it is cosmopolitan, flexible, and immersed in a globalized economy (Fleras and Elliott, 2002:32). In today's Canada, the notion of multiculturalism is an inherent part of what Risse-Kappen (1995) calls "the collective identity of the nation."1

The reforms to immigration legislation in the 1960s and 1970s set up a points system in order to create a more solid, inclusive migratory regimen, moving away from the selection of migrants based on origin and ethnicity. It is a system rooted in the prospect of taking full advantage of human capital based on the individual traits of the migrants selected taking into consideration education, age, job opportunities in Canada, language, kind of abilities, and occupation. The Canadian government's labor migration policies seek to select individuals who will be economically productive in the shortest possible time after their arrival. To do that, the system is expected to favor individuals with profiles and abilities that can be used to favor the Canadian economy immediately or who can go through training and the revalidation of their credentials (Gabriel, 2006). Another key aspect of these reforms was the introduction of ethnic diversity as a positive aspect of immigration (Rodríguez-García et al., 2007). Today, Canada's immigration regimen is cemented on a robust legal framework oriented to promoting the participation in society of the different ethnic groups seeking to eliminate the barriers blocking it, all under the umbrella of international human rights and in accordance with the preservation and intensification of the country's cultural heritage. This legal framework's effectiveness is at the very least controversial. For its less severe critics, it is a substitute for an anti-racist policy. For its most severe critics, what we have here is a model that uses liberal rhetoric to sell diversity in order to reinforce the political and economic interests of dominant groups (Teelucksingh, 2006).

So-called "global" cities like Toronto are often contradictory.2 On the one hand, they require the external flows of human and financial capital, but, on the other hand, they are not willing to recognize the credentials of the highly qualified, and the contributions of those who are not as highly qualified often go unnoticed. Global competition to attract qualified immigrants means that the qualified are given precedence to the detriment of other immigrants who, despite not having high levels of formal education, might be a better fit for the Canadian labor market (Gabriel, 2006). The outcome is that that labor market is segmented. On the one hand, one segment is made up of visible minorities in low-paying jobs in sectors such as manufacturing, hotels, and the food and beverage industries. Jobs in these areas are usually badly paid and temporary. Another segment is made up of highly qualified immigrants who are underemployed or in subordinate roles in areas like education, government, and business, where the work is stable and well paid. A third segment made up of dominant groups enjoys privileged access to the labor market and can be more easily found in stable, well-paying jobs in areas like finance, government, and education (Lo, 2008). This labor market is also very competitive with much greater supply than demand. In Ontario, estimates state that only 35 percent of immigrants with professional training in fields requiring some kind of certification or licensing enjoy professional status in accordance with the qualifications in their specialty areas in the first four years of their stay in Canada (Lo, 2008:98). The greatest discrepancy in job category levels and prestige are found among immigrants with university degrees: 23 percent achieve a post similar to the one they had in their country of origin in the first year of their stay in Canada (Grenier and Xue, 2010).

With regard to the place of origin and ancestry, we can also see patterns formed over decades of immigration. Immigrants from Northern and Western Europe, except for those from France and England, are present in equal numbers to Canadians in all sectors of the workforce with three exceptions; in services, retail, and food and beverages, they are less represented. Immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe, including Italy, Portugal, and Poland, are over-represented in manufacturing and construction. Those from East Asia, particularly China, are over-represented in manufacturing, food and beverages, and hotels, but also in transportation, administration, and support services (Lo, 2008). Immigrants from Latin America are concentrated in administrative jobs, in the health sector, financial sector support services, and cleaning services. Mexican immigrants are dispersed in cleaning, construction, and food services, as well as business and financial sectors. The latter are a growth niche for the creative class.3

The Canadian Experience

When immigrants' integration into the Canadian labor market is studied, the notion of the Canadian experience will almost inevitably come up. We read about it in scientific research and in all kinds of publications; we hear about it in conversations at the office and in the cafeteria. The most tangible part of the Canadian experience refers to a type of "devaluing" of the immigrant's job experience and preparation because he or she has foreign credentials and no job experience in Canada. However, the Canadian experience also refers to a kind of learning. To understand this less perceptible aspect of the Canadian experience, it is useful to refer to the work by the Canadian Experience Project Team, led by researcher Izumi Sakamoto (2013). Sakamoto and her team argue that the reason recently arrived skilled migrants do not find work is linked more to soft skills (communication and social skills) than hard skills (technical knowledge). These abilities are a central component of the Canadian experience, would only with great difficulty be expressed in a resume, and play little part in the Canadian immigration points system. They do, however, manifest themselves and develop in the personal contact between job applicants and employers. Some examples mentioned by the Canadian Experience Project are adjusting dress and etiquette codes, not interfering in the personal space of others, knowing what topics of conversation are appropriate,4 and being selective in the kind and number of questions to supervisors. In the discourse of the Canadian experience, the devaluation of "soft" skills is expressed as "not being familiar with workplace culture in Toronto" or "not knowing how to handle oneself in multicultural work spaces." It is assumed that after a "learning curve," the migrant will gain access to the job market in the same conditions as native-born workers.

Research Design

The material for this article comes out of a research project about trajectories of cultural, socio-political, and labor/economic integration of skilled Mexican migrants in multicultural societies carried out in Canada and Germany (Peña, 2013). For this project, I developed a two-dimensional analytical matrix: the "agent" dimension focuses on the immigrant and includes demographic variables like age, marital status, and gender, as well as indicators used to characterize skilled migration such as language skills, formal education and abilities. The other part of the matrix is the "context" dimension and is dedicated to the receiving country covering common themes featured in literature about immigration and integration such as racism, access to political rights and employment. I dealt with the issue of the Canadian experience as part of the factors of integration in the labor/economic sphere in Canada. The techniques used for gathering and analyzing the information in this project were selected and designed to study the trajectories of insertion from the respondents' subjective frames of reference. These techniques include discourse analysis, analysis of trajectories, observation in the respondents' natural surroundings, and grounded theory. The main instrument for gathering data was semi-structured, conversational interviews. First, I contacted key respondents, included in the table as leaders, in each of the creative groups. The rest of the respondents were contacted using the snowball technique based on information from the key respondent. Other respondents were found through Instituto de los Mexicanos en el Extranjero (Institute of Mexicans Abroad) and Red de Talentos (Talent Network) data bases. I began by carrying out five interviews for each creative class group in order to adjust the questionnaires based on the information received. I continued interviewing until I thought that, given the time and resources available for doing fieldwork, a satisfactory theoretical saturation point had been reached in each creative group. Lastly, the data gathered were organized and analyzed using the Atlas Ti interview codification program.

For the interviews, I selected men and women born in Mexico who had resided at least two years in Toronto and who had jobs in line with the concepts of capital and creative class. The objective was to gather data about individuals residing permanently in the destination country and who had already gone through the first experiences in their integration process. With this in mind, I can say that the objects of study of this research project were Mexican men and women whose migratory experiences are related to the production of creative capital and their integration into the labor market of their destination city. They include Spanish-language rock musicians, multicultural artists, theater directors, and choreographers; area managers, human resource directors, and promoters of associations of Mexicans; students of engineering, nutrition, and international relations; owners of small restaurants and energy crystals and tea shops, coordinators of international consulting firms, financial analysts, and mid- and upper-level management personnel in banking institutions. I did a total of 30 interviews between May and July 2012 in the Toronto metropolitan area in respondents' workplaces as well as cafés and other informal venues. The most highly represented group was that of academics and scientists, followed by businesspersons persons in the financial sector.

I interviewed 18 women and 12 men. These figures suggest that migration of the creative class coincides with trends in international migration: women have a growing presence in migratory flows in general, including among the qualified. Marital status varied widely among the interviewees. We can identify four main variations: 1) interviewees who were single during the entire migratory experience until the interview; 2) interviewees who were married to another Mexican when they arrived in the country; 3) interviewees who had been married to a Canadian in Mexico prior to arrival; and, 4) interviewees who were single when they arrived and then married a Canadian national. The average age was 27,5 with an average of five and a half years residence in Toronto.

Most of the interviewees come from states in Central Mexico and Mexico City, the latter being most common among them: almost 70 percent lived in the Federal District before emigrating. Another noteworthy city of origin was Monterrey in Northern Mexico (five interviewees); then Guadalajara with four. These three cities made up 81 percent of those interviewed. The rest were from different cities around the country like Jalapa, Querétaro, Puebla, and Hermosillo, among others. Based on these figures, we can add another characteristic of the interviewees: they are urban migrants, mostly from Mexico's main urban areas. All of them entered their respective destinations with proper documentation. One common form of entry was using a student visa (54 percent), and later, after finishing their studies, obtaining permanent residency.6

The Discourse of the Canadian Experience in the Words of the Mexican Creative Class

A great deal of research has shown that structural barriers exist specific to the condition of being a foreigner, such as isolation from key information, lack of informal networks, and problems in the certification and validation of professional credentials, all of which make migrants' insertion into the labor market difficult. In the case of Toronto, we also find another kind of barrier stemming from a supposed common-sense knowledge of how a multicultural society's labor market should operate. This kind of "preparation for diversity" is based on "soft skills," which implies the transfer of abilities and knowledge not only from one cultural context to another, but to one that is multicultural. It is in the Canadian experience where these barriers are rooted, translating into greater control and discretional decision-making for employers when hiring foreigners.

The Multiple Dimensions of the Canadian Experience

The Canadian experience is built around a discourse of common sense that maintains that immigrants suffer from "labor devaluation" because they have foreign credentials and lack work experience in Canada or in Canadian companies; for that reason, they have to go through a "learning curve" and develop new skills. We can see this dimension in the words of one of our interviewees: "In Toronto, they want qualified people, but when it comes right down to it, they ask for Canadian experience, that you have worked here. So, tell me how I'm going to get that if you don't give me a job!" (Sandra, B Group).7 As we can see in the following examples, the Canadian experience is understood as a loss of job status and a hindrance to achieving occupational goals.

You hear there's work in Canada and that they need doctors and engineers, but when you get there, you find out that they consider a [bachelor's] degree in engineering here like you were a technician or a mechanic. So then you can't find a job, and you don't know what to do before you go to authenticate your studies. I wouldn't know if this is to attract qualified people and give them low-level jobs so they can then climb up the ladder instead of bringing in immigrants who are going to stay forever at the same social level, usually a low one. It might be that, or it might just be inefficiency in that they don't announce the authentication processes in Canada (Martin, SS Group).

You see this with dentists, doctors, and engineers who can't exercise their profession without a license. Doctors working as nurses, highly trained dentists working as dental hygienists. That's been a shock for me. All the stumbling blocks that an immigrant has to overcome to have a high-status job, to call it that; a job that is socially well thought of, is very hard. The possibilities for success are very small (Elena, SS Group).

Everybody who has had the guts to come on their own has been really hard-hit because, a professional with advanced degrees and lots of job experience has to start from scratch (Emma, BF Group).

It is no big discovery to find that certain occupations require authentication of credentials or certificates. The Canadian experience is not just a process of certifying credentials and learning certain skills. I also found another dimension that involves learning about how the multicultural labor market works in Toronto specifically. Due to her work as a head hunter, Hilda has thought deeply about this part of the Canadian experience:

When you get here, people aren't sure if you're ready for... diversity. For example, some communities are highly qualified in certain areas like technology, they're really masters of technology, but they can't deal with people; they can't interact socially the way you need to to work harmoniously. Their technical abilities are very high, even higher than people who have studied here, but their personal, social skills, their ways of dealing with people just aren't there. So, even if you've been a doctor or an engineer in a country, in charge of 50 people, and nobody could touch you because you were the most brilliant, when you get to Canada nobody knows how you treated those people, what kind of person you are. Lots of people think that if you were a great engineer in Mexico, you expect to be a great engineer in Canada; but to start with, you aren't familiar with the market; you don't know how you're expected to treat people. In Mexico we don't have the cultural diversity that exists in Toronto. How can you say you've mastered handling people if here we're going to put you with other kinds of people? (Hilda, L Group).

I was there when Joel, from the financial and businesspersons' group interviewed a young man who I later found out had just finished his MBA at one of the business schools with the toughest selection criteria in Canada. When he was asked about this person's chances of getting the job, Joel talked about another aspect of the Canadian experience unrelated directly with foreign credentials or any kind of formal education. Joel mentioned two issues: fit and the reduction of risks and uncertainty. These issues mean that in order to be hired, the candidate has to have a profile that inspires confidence and security to avoid further "polluting" the job environment already fraught with the constant discomfort involved in multicultural social relations.

A person's having a degree from here inspires confidence in the one seeing it. This candidate has job experience in Hong Kong, and that can even affect employers who are not Canadian. In finance, we're a little "risk adverse" in the sense that they think a candidate needs exposure to local surroundings or to have job experience in companies from here for them to then think they can have confidence in him (Joel, BF Group).

A profile that inspires confidence and displays the necessary interpersonal skills seems to be key for being what the employers call "the right fit." Interestingly, as we can see from the work of the Canadian Experience Project, employers argue that knowing who is the right fit is a matter of training and intuition on their part. The right fit is partly based on common sense, the individual's image, and his/her interaction with the employer. The fit is yet another dimension of the discourse of the Canadian experience, complicating its assessment as a discriminatory practice or a "natural" selection mechanism. The argument of the natural mechanism was much more prominent in the case of interviewees with higher job status. To respond to this issue, we need to refer to a discourse of common sense found among our respondents.

There's no Racism in Canada

The experiences of my interviewees lead me to conclude that the Canadian experience operates within a framework of a classification of foreigners that, far from being random and objective, is based on subjective criteria of social power that take into account factors such as place of origin, ethnicity, physical appearance, accent and fluidity, apparent social class, gender, and age. These factors come into play at the moment when the migrant interacts with potential employers. To understand the way the respondents experience this process, it is necessary to refer to the discourse of "there is no racism in Canada." My argument is that the practices of the Canadian experience are part of a discourse that I call multicultural racism (Peña, 2013). Multicultural racism is based on a legalistic discourse, which, by presenting multiculturalism as a public value and public policy, facilitates the uncritical acceptance of exclusionary practices and racist attitudes in everyday socialization and the racialization of public spaces (Teelucksingh, 2006). This makes it possible for these practices to become part of work spaces and operate as a natural part of the experience of living in a multicultural Canadian society. In everyday socialization, this discourse in the form of the Canadian experience is within reach of employers-many of them recent immigrants themselves-to justify discriminatory practices in non-racist or non-xenophobic terms.

Some interviewees did use language that pointed to discrimination and racism. For example, when reflecting on instances of racism in Toronto, Andrés (BF Group) said, "Day to day, I don't see racism. You see it more markedly when you go to ask for a job and they give it to the white Anglo-Saxon instead of you." However, it is still worthy of note how the language for discussing inequalities in the field of employment almost never touches on the concept of discrimination or racism. In line with what Vila (2007) argues about Mexican migration to the United States, for certain migrants, emigrating from the South to the North implies an almost utopian certainty of instantaneous social and economic improvement. This belief reminds us of the power of some discourses to produce a surplus of meaning that literally structures migrants' perception of their situation in the receiving countries. Many migrants believe that their lives will be better in another place; and that is one of their main motivations for moving to another country. This imaginary certainty of improving their lives by emigrating becomes part of the cognitive tools they employ to define concepts such as racism and discrimination. One example from the group of bohemians is the following:

As far as I know, none of my friends has faced direct racism that can be expressed in words. I see it more in the case of work: maybe paying you less, letting you work more, or things like that. That does exist, but I don't see that as racism. I see it as a process that sooner or later, I'll get through, and I'll start a new stage in which that doesn't affect me as much. (Fer, B Group).

The vast majority of the interviewees interpret their Canadian experience using the discourse of "there's no racism in Canada." In fact, as we have seen in some of the foregoing quotes, several interviewees think that the feeling of rejection arises from unrealistic expectations on the part of recent arrivals.

I understand the Canadian experience as a way of their saying, "Do you know what we do here?" But it becomes an incredible barrier, because, how are you going to get that Canadian experience if you don't get that first job? I haven't felt that the average Canadian is racist per se. I think that most are willing to give you a chance if it doesn't cost them any money. You feel that you're going to be in good shape from the start, but that's a mistake. Most people who get jobs get them by fighting for them. After you get through that stage of validation and you start working, that's when you're going to have a good salary, and then you're going to be in good shape (Patricia, B Group).

I think that's not racism; it's a preparation you don't have; people don't arrive prepared for that. Now, we're talking about an educated group of people who had privileged positions in Mexico. When you get to Canada, that privileged position no longer exists. You no longer have your network of contacts, the lifestyle you had in Mexico; you're middle class and part of the masses. All these elements make you feel that you no longer have what you had (Hilda, L Group).

Canada is multicultural. There are very few Anglo-Saxons; the mixture is very wide. You don't feel discriminated against; it's not that they don't discriminate against you; you just don't feel discriminated against, which is different (Ben, SS Group).

These testimonies show how the respondents are incapable of perceiving the power relations that come into play in the social construction of identity, cultural production, and the struggles for resources in terms of racism and discrimination. The imaginary of a Canadian national multicultural identity reinforces the "there's no racism in Canada" discourse. In line with what Essed wrote in 1991, evaluating an event in terms of racism is conditioned upon the social basis of knowledge in which it occurs. Within a social structure dominated by multicultural racism discourses, certain actors can lack a cognitive framework that allows them to understand specific acts in terms of racism. Given that, saying "It's not that they don't discriminate against you; you just don't feel discriminated against," reflects the actor's lack of the cognitive tools to identify events in terms of racism (Essed, 1991).

Only one of the participants in the group of businesspersons and people in the financial sector talked about an event that he described as "direct racism":

Where I worked, the company's number two began to humiliate me in front of everyone just for being Mexican; for violence that was taking place and the Canadians who were being murdered. He started saying that my country was the most corrupt in the world and external things that aren't under our control. He continued for about an hour and a half, vomiting all his rage for I don't know what reasons. It was really hard because it was in front of a lot of people and nobody said anything. There isn't much diversity in the company. Everybody is of Anglo-Saxon extraction. I was the little light that attracted attention, and it became clear to me that I was the outsider. By the end, it made me cry and feel very bad. It was traumatizing (Joel, BF Group).

However, even after that disagreeable incident, Joel continued to reproduce the hegemonic discourse: "Yes there is discrimination and I have been the object of it, but I'm aware that it's not generalized and being Mexican doesn't give me a bad image" (Joel, BF Group).

Something particularly noteworthy in this case is how the "there's no racism in Canada" discourse survives the xenophobic feeling that is obviously present. This is due in part to the interviewees' need to construct their identity using a cognitive framework in which emigrating to Toronto (moving from a poor to a rich country as a representation of improving quality of life) is a panacea for social and economic improvement, and no reality is able to contradict that. The testimonies that follow reflect a tendency to normalize and trivialize notions of difference and hierarchy in important spheres of society. I call these narratives "there's no racism, but..." They consist of transforming an event of generally unacceptable racism or discrimination into one that is acceptable by relating it to a particular context that excuses it with reference to some form of reasoning that justifies it. Racism doesn't exist, but "ignorance" or "population biases" do, or "getting ahead is harder as a migrant without an English [ancestry] profile"; "they're filters"; and "there's some prejudice." There's no racism, but "I've felt ignorance on the part of many Canadians with regard to Mexico. It's not a negative feeling, but I do think there're a lot of clichés and stereotypes" (Adán, L Group). There's no racism, but "there're some prejudices. And not only prejudices from Canadians of British descent, but from other groups of Canadians. For example, they assume you're the model of the Mexican macho; I suppose you also assume things about other nationalities" (Pedro, SS Group).

We can find other examples of multicultural racism in the following descriptions of the stumbling blocks in finding employment. This respondent fails to identify an act of racism or a factor responsible for Mexicans' marginalization in the labor market. The problem identified in this kind of testimony is not the practice of marginalization, but the ability of people themselves, in these cases, the agent's preparation and efforts:

There's no racism, but...

there can even be a kind of bias on the part of the population according to the color of your skin even for people from Canada. In the museum where I work, I've noticed that Hispanics have posts where they have to do less talking. My job is talking; I have to talk to children and adults and I see very few Hispanics in these kinds of positions. Most people with dark skin work in technical jobs, cleaning, repairs, and things like that (Gabriel, SS Group).

There's no racism, but...

the highest positions are for older Canadians and not first or second generation. I think that moving up the ranks is hard. Yes, it's a matter of time, but it's also harder as an immigrant who doesn't look white Canadian, or British (Alicia, BF Group).

Multicultural racism seeks to celebrate cultural diversity, but as can be seen in the following two statements, experiencing diversity is reserved for the moment when you pick somewhere to have dinner. For other times, such as during hiring, diversity needs to be "filtered." There's no racism, but "there are ways of filtering. It's like a kind of racism, but it's also a way... It's not that they're better, but it's better to try someone you know than to experiment with somebody new" (Penélope, ss Group). There's no racism, but "there are filters in the politically correct discourse. Everyone knows that certain things cannot be said; you can't say 'I don't like certain people,' because Toronto is an experiment in that kind of artificial filters" (Genaro, BF Group).

The absence of a storyline of racism in the discourses of the creative class points to the conditioning of their cognitive frameworks, influenced by the collective imaginary of migrants in Toronto: Toronto is a city of immigrants, and therefore its inhabitants are tolerant and educated in relation to diversity. The reason they emigrated to Canada is because, since it is a multicultural society, racism must not exist there. This assessment is also influenced by the discourse of Mexicans' experience in the United States. The cognitive frame-work with which the respondents assess their experience in Toronto acquires a more positive tone compared to their opinions about the treatment of Mexicans in the United States.

That's something I liked very much about Canada, especially Toronto. I can walk down the street like anybody else. It's very different from what you experience in the United States. I was in Arkansas and Louisiana, and there you feel it a more; from the time you cross the border, from [dealing with] the officer, they look at you like you're going there to work as an "illegal" in the fields. (Pedro, SS Group)

In Canada I haven't run into anyone who doesn't like Mexicans. I've never felt discriminated against like in the United States. I didn't go there precisely because I didn't want to go through that. (Ben, SS Group)

At least among those members of the creative class interviewed, a storyline persists that maintains that xenophobia and marginalization of Mexicans are things that happen in the United States, while Canada's image continues to be the antithesis. I think this difference rests in part on the centrality and visibility that the interviewees attribute to the discrimination against and marginality of Mexicans in the United States, even those with qualifications and proper documentation. By choosing Canada over the United States as their destination, migrants adopt a narrative that spans everything from the denial of racism in Canada to the recognition of more subtle forms of multicultural racism as normal practices in a multicultural society.8 If xenophobic feelings and practices of marginalization against Mexicans in Toronto exist, they are not sufficiently long-lasting, central, and visible in the experience of the interviewees for them to assess them as such. The "invisibility" that Mexicans of the creative class in Toronto enjoy contributes to the fact that marginalization and xenophobia are not part of their storylines. The narrative proof of racism, in and of itself, makes it impossible to either confirm or deny a hypothesis of marginalization of Mexicans in the labor market. What we can affirm is the construction of a common cognitive framework that maintains that even marginalization and racism are better in Canada than in the United States. Analyzing the Canadian experience from the standpoint of the affirmation that "there's no racism in Canada," we can arrive at the following conclusion: the Canadian experience is a process of filtration that operates through non-institutionalized practices produced and reproduced in complicity with the immigrants themselves as part of their imaginary and the expectations motivating their moving. In practice, the discourse of the Canadian experience functions as a kind of internal migratory control complementing or correcting the failings of a porous immigration regime designed within a multicultural ideology that does not reflect the reality of the diversity of cities like Toronto.

For the members of the Mexican creative class interviewed, the Canadian experience is a barrier for integrating into the labor market justified in terms of a learning process about Canada's labor culture and nourished by a discourse that states that "there's no racism in Canada." This connection facilitates the uncritical acceptance of exclusionary practices, racist attitudes in everyday socialization, and a racialization of the workplace. This makes it possible for these kinds of practices to become part of the spaces of socialization and to operate like a natural part of the experience of living in a multicultural Canadian society.

Conclusion

These interviewees' experiences show that the Canadian government's emphasis on selecting qualified immigrants through a points system has not been seconded by the development of a labor market favorable to labor migration. The practices of the Canadian experience reveal a disparity between migrants' labor expectations, the demands of the local labor market in terms of occupational distribution, and the Canadian government's multicultural discourse. The official Canadian discourse of multiculturalism states that its aim is to eliminate xenophobic practices and racist references, de-contextualizing them from issues of difference based on ethnicity and gender, thus transforming them into narratives about community and civic values, the work ethic, filters, and learning curves. In everyday practice, the social structure of work in Toronto has non-institutionalized processes or "filters" of marginalization and discrimination against migrants that make their integration into the labor market more difficult, no matter what their qualifications.

The existence of barriers like requiring Canadian job experience confirms that labor immigration policies should go beyond entry controls. A comprehensive labor immigration policy implies a balance between control mechanisms designed to achieve planned, orderly, secure admissions and concrete actions in the labor market to foster transparency, equity, efficiency, and efficacy in hiring processes and that generate spaces for making complaints about acts of xenophobia, discrimination, and racism. Measures like the Fair Access to Regulated Professions Act passed in 2007 by the Ontario government to establish clear processes for evaluating immigrants' credentials and professional experience. This law links people in Ontario's 34 regulated professions with language training programs offered by universities and private institutions, job opportunities, and legal advice. In addition, the competent authorities aim to shorten processes for obtaining licenses and credentials, as well as to make them more transparent. This law is only a first effort of its kind in Canada's legal sphere and does not deal with non-institutionalized dimensions of the Canadian experience. Nevertheless, the Conservative Party's immigration agenda, fostered by its leader Stephen Harper, has been criticized for its preference for short-term employment migration. This position has been characterized as exclusionary, inequitable, and the cause of frictions between foreign and Canadian-born workers. It is also accused of dehumanizing the immigrant selection process when it prioritizes criteria that assess migrants based on their capacity to make an immediate contribution to Canada's economy. One example is the introduction in 2008 of Bill C-50, designed to attract highly skilled migrants and international students to the detriment of other kinds of migration, like that whose purpose is family reunification or is rooted in humanitarian causes. For some, this bill sought to give the Canadian government discretionary powers to manipulate entry and permanent stay criteria, giving rise to practices of labor exploitation and racism (Ashka, 2010).

As the International Organization for Migration (2010) suggests, labor migration policy must be designed within a frame-work of shared responsibility between countries of origin and destination, and must also take into account "human factors," which go beyond human rights, such as the goals, motivations, and expectations of both migrants and employers, considering the migrant its central axis. Shared responsibility implies that the countries of origin have the obligation to ensure the protection and well-being of their citizens abroad by seeking to influence the conditions of their integration into the labor market. In the specific case of the creative class migrant's profile, an appropriate policy would make available to potential migrants clear information in their own language about legislation, labor rights, labor market conditions, and hiring processes. This information must also alert migrants to practices like those of the Canadian experience. In particular, migrants must know that, despite the fact that hard skills often prevail, his/her insertion into the labor market also depends on soft skills, which are of great importance for overcoming barriers like the Canadian experience.

On the other hand, destination countries must complement their selection mechanisms with objective information about working and hiring conditions, combat misleading advertising by private employment agencies, and provide training in the place of origin. Another effective measure is to involve the private sector in strengthening and developing training programs in both "hard" and "soft" skills for migrants in their places of origin. I propose that, in designing shared-responsibility policies on labor migration, bilateral accords like the program for agricultural workers or the Mexico-Canada Mechanism for Labor Mobility under the aegis of the Mexican government's National Employment Service, offer space for innovation and trying out migratory labor policies that benefit all kinds of migrants and employers, as well as both the country of origin and the receiving country.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)