Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

Share

Migraciones internacionales

On-line version ISSN 2594-0279Print version ISSN 1665-8906

Migr. Inter vol.8 n.2 Tijuana Jul./Dec. 2015

Articles

Believe, Migrate, Circulate: A Methodological Proposal for Analyzing Migratory Experience and Religious Change from Localities of Origin

Creer, migrar, circular: Propuesta metodológica para el análisis de la experiencia migratoria y el cambio religioso desde las comunidades de origen

Olga Odgers Ortiz*, Liliana Rivera Sánchez** y Alberto Hernández Hernández*

* El Colegio de la Frontera Norte. Correo electrónico: odgers@colef.mx, ahdez@colef.mx.

** El Colegio de México. Correos electrónicos: rivesanl@colmex.mx.

Date of receipt: July 16, 2014.

Date of acceptance: November 4, 2014.

Abstract

Using mixed methods, in this paper we hold that the relationship between international migration and religious change can be analyzed from localities of origin as strategic sites of observation. Thus, examining the relationship between migration and religious change means simultaneously considering the two-way impact, of migration on religious change, and of the role of religious identifications on the formation of migrant networks. From the case studies in this research, we conclude that international migration is an important resource, which acquires two modalities: on the one hand, it reinforces the traditional religious practices of believers and on the other, it promotes religious change, specifically religious conversion. It is, in short, the perception of diversity and the sense of religious otherness that are transformed by the migration experience.

Keywords: migration, religion, religious pluralization, Morelos, Mexico.

Resumen

Mediante la utilización de métodos mixtos, se propone el análisis de la relación entre la migración internacional y el cambio religioso, tomando las comunidades de origen como punto de observación privilegiado. Se propone que esta relación debe observarse en su doble vía: el impacto de la migración en el cambio religioso y la relevancia de las identificaciones religiosas en la formación de redes migratorias. A partir de los casos estudiados, se concluye que la migración internacional puede constituir un importante recurso para los creyentes, ya sea para el reforzamiento de las prácticas religiosas tradicionales o para apoyar procesos de conversión. En todos los casos, la experiencia migratoria transforma la percepción de la diversidad y la alteridad religiosa.

Palabras clave: migración, religión, pluralización religiosa, Morelos, México.

Introduction

Although a number of outstanding studies addressing the relationship between migration and religious change (Gamio, 1971 [1930]; Herberg, 1983 [1955]) have been published since the mid-20th century, the growing interest in this phenomenon appears to coincide with the emergence of multicultural metropolises or global cities (Sassen, 1991), where religious pluralization, linked to the intensification and diversification of migration flows, achieved unprecedented visibility (Warner, 1993; Warner and Wittner, 1998; Kurtz, 1995; Orsi, 1999; Cadge and Ecklund, 2007).

Consequently, this approach prioritizes the study of relations between host societies and the new religious minorities. In particular, it highlights the interest in observing the relationship between religious pluralization and assimilation, paying particular attention to the organizational forms that migrant communities develop in the contexts of arrival, thereby establishing a close link with studies on ethnic incorporation. This research will continue to be undertaken, leading to new studies on aspects as diverse as the function of churches in cultural and socioeconomic incorporation (Hirschman, 2004), the specificities of religious revivalist movements in integration (Glick Schiller, Caglar and Guldbrandsen, 2006) and the religiosity of the second generations (Diehl and Koenig, 2009).

Subsequently—during the first decade of this century—new studies were added to this initial analytical perspective, which highlighted the importance of the links migrants maintain with their places of origin, in order to posit that rather than simply reproducing the religious practices and beliefs of their places of origin in the places of destination, new migrant communities construct intricate networks of relationships in which traditional ritual practice acquires new meanings and becomes a resource for the revitalization of symbolic links—identity and the sense of belonging—and specific relations—circulation of goods and services, establishment of padrinazgos (systems of patronage), and so on (Levitt, 2009, 2011; Fortuny, 2011; Rivera, 2006; Odgers, 2008; Hirai, 2010). Thus, the religious sphere may constitute a space where previous organizational structures are transformed and expanded (such as guilds or systems of responsibilities), simultaneously incorporating those who migrate and those who remain, and lending new collective meanings to traditional religious practices.

In the same vein, recent work (Levitt, 2012) suggests the need to transform the analytical perspective from which religions have traditionally been studied, in order to recognize the importance of mobility in the practices, symbols and beliefs that move across national borders, forming circuits in which new relationships and connections are constructed on an everyday basis. In this regard, the proposal does not seek to deterritorialize the study of religions, but rather to use a transnational perspective to observe the new geographies shaped by mobility.

By highlighting mobility, this approach to the relationship between migration and religion opens up the possibility of reincorporating places of origin into the reflection, without removing them from a broad spatial perspective. Moreover, according to Hagan (2008), it is essential to know the characteristics of the religious field that precedes migration, not only as a point of reference for subsequent contrasting, but also because the religion, faith and networks established by religious communities may constitute factors that influence the decision to leave—or stay—for potential new migrants.

Paradoxically, despite the importance and breadth that the perspective of transnationalism has acquired in the academic sphere, this has not been reflected in an equally abundant production of publications that specifically analyze the relationship between migration and religion, observed from migrants' localities of origin. Thus, for example, studies addressing the impact of migration of various origins on the religious field in the United States, or the impact of North African immigration on Spain, France and Germany are considerably more numerous than studies examining the effect of those same transnational migratory flows on the transformation of religious practice in Mexico, Algeria, Morocco and Senegal.

In order to advance in this direction, this paper focuses on the analysis of the effects of international migration—and religious mobility conveyed in this way—on the transformation of beliefs, practices, institutions and communities in migrants' hometowns. The point is obviously not to separate the analysis of religious processes in these research sites of the mobility that transcends the local sphere. On the contrary, the proposal involves using localities with high rates of migration intensity as an observatory for specifically analyzing the implications of mobility. This perspective enables one to ask, for example, what kind of relationships are established in specific "meeting places", between the elements in circulation and those that have already been established (Levitt, 2012), how mobility transforms existing symbolic boundaries, how new elements that circulate progressively settle, gradually adding new layers of meaning to existing ones. In this respect, according to Levitt, the aim is to observe the localities of origin as:

Potential sites of clustering and convergence, which once constituted, circulate and re-circulate, constantly changing as they move. The resulting configurations are not purely local, national or global but nested within multiple, intersecting scales of governance, each with its own logic and repertoires of institutional and discursive resources (Levitt, 2011:12).

This paper therefore seeks to advance the construction of theoretical and methodological tools in order to understand the contemporary transformations of the religious sphere, which took place in the wake of the intensification of mobility in the Mexico-US immigration system. Specifically, without underestimating the importance migration may have in understanding the persistence and consolidation of religious beliefs, we analyzed whether the adoption of a new creed, in other words, the change of religious affiliation and/or belonging as well as the transformation of religious practices in contexts with high levels of international migration intensity is related to mobility, particularly due to the effect of the return of international migrants in their capacity as bearers of practices, symbols and ideas concerning the religious sphere, without overlooking other endogenous change factors.

The analytical strategy includes a multi-method research design, involving both qualitative and quantitative analysis techniques: statistical analysis of several indicators and demographic variables from the Censos de Población y Vivienda 1970-2010, the use of geographic information systems, the design of different types of interviews (mainly semi-structured and in-depth), ethnographic research as well as the analysis of historical documents on the formation of the regions studied.

Selection of Research Sites

In order to identify the potential impact of mobility on the religious sphere of the localities, we decided to focus the study on migrant-sending areas, where it would be possible to identify recent changes in people's religious affiliation. The study would therefore focus on determining how such changes would be associated with international migration, or conversely be caused by internal or regional factors. At the same time, this choice would make it possible to identify how religious affiliations impact on believers' mobility practices.

To guide the choice, we began with the results obtained within the framework of the project Profiles and Trends in Religious Change in Mexico 1950-20001 where, on the basis of the study of the relationship between the rate of migration intensity and religious diversity in Mexico, it was possible to identify three main trends (Odgers and Rivera, 2007; Odgers and Ruiz, 2009):

1. Traditionally migrant-sending regions, which combine high rates of migration intensity with low religious diversification.

2. Regions that maintain significant religious diversification and high migration, but where the intensification of migration was later than the decline of Catholicism, meaning that it is not possible to associate religious pluralization with the experience of international displacement.

3. Lastly, certain specific regions (mainly the state of Morelos and some municipalities in the state of Oaxaca) where religious diversification and migratory intensification have coexisted since the late 20th century.

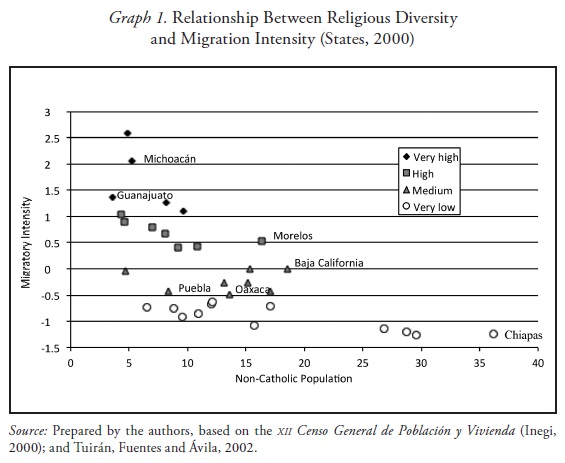

In this respect, as shown in Graph 1, states with higher migration intensity rates are those with high levels of Catholic affiliation; while those where the decline in Catholicism is more pronounced participate less in international migration flows.

The case of the state of Morelos, however, is striking, since in 2000, it already displayed a high rate of migration intensity, in addition to over 15 percent of non-Catholic religious affiliation. While these data do not make it possible to establish a causal link between migration and religious change, they do enable one to identify the state of Morelos as a geographical space in which both processes occur simultaneously.

On the basis of this initial statistical analysis, the state of Morelos was selected to advance the work in greater depth. While it is true that the relatively recent nature of international migration originating in Morelos constitutes a limitation—it is not possible to observe migratory networks with the same maturity as those in the western center—for research purposes, this state proved particularly useful because of the convergence of its processes of religious diversification and migratory intensification.

Thus, during a second stage, we proceeded to change the scale in order to observe the localities and municipalities in the state of Morelos. Specifically, at the municipal level, we georeferenced the index of religious diversification as measured by the decrease in Catholicism and the International Migration Intensity Index2 from the last census.

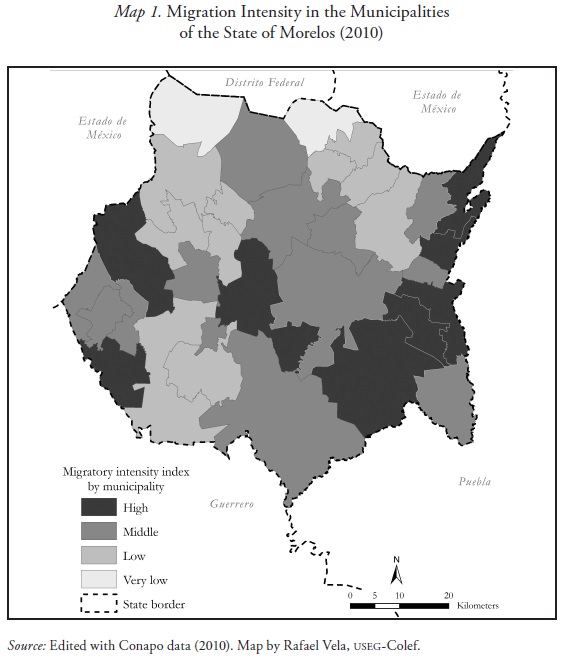

As shown in Map 1 for 2010 in the state of Morelos, municipalities with a higher rate of migration intensity clustered in the east (five municipalities), the center (two municipalities) and the west (two municipalities). In all cases, these are relatively recent migration flows, as opposed to the central-western region of the country, where migration dates from the early 20th century. In the state of Morelos, migration flows to the United States correspond to the second quarter of the last century, and to even more recent periods in some regions (Rivera and Lozano, 2006). Also, unlike the traditional migrant-sending region, Morelos residents choose a wide range of migratory destinations in the United States. As will be seen below, this geographical dispersion hampers the consolidation of migration networks between migrants from the same state and the concentration of migrants from the same origin in certain destinations, even though large agglomerates are beginning to be seen, as in the case of migrants from Axochiapan in Minnesota, for example (Bobes, 2011).

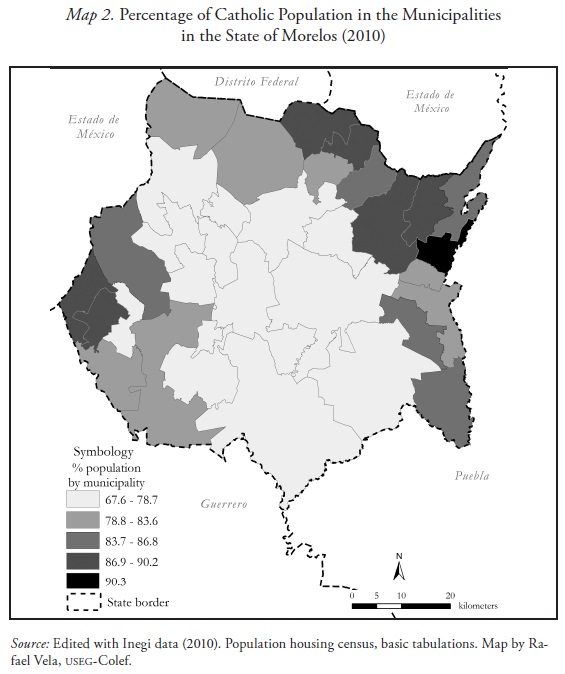

At the same time, as shown in Map 2, by 2010 the municipality of Zacualpan had the highest percentage of Catholic affiliation in Morelos, while a wide swathe crossing the state along a northwest-southeast axis concentrated the municipalities with the greatest decline in that denomination. Like migratory intensification, the process of religious diversification in Morelos is relatively recent, dating from the last decades of the 20th century. This process has taken place within a context of hegemonic yet heterogeneous Catholicism: unlike traditional migrant-sending regions, Catholicism in Morelos—with variations by region—is characterized by the significant development of grass-roots communities (GRC) and the mark of Bishop Sergio Méndez Arceo, linked to liberation theology.

On the basis of the data presented, and after some exploratory field visits had been conducted, the municipality of Tepalcingo was selected, since it met the criteria, both because of the religious diversity of its population, and the intensity of migration to the United States, with both processes temporarily coinciding. Moreover, three sites in the selected municipality (Zacapalco, Ixtlilco el Grande and the municipal head town) have high rates of non-Catholic population, despite the age and popularity of the Catholic feast of the Lord of Tepalcingo, held annually in the municipal head town and being in the same location as the most important religious sanctuary in the state of Morelos.

By way of a contrast, we also selected the municipality of Zacualpan de Amilpas was also selected because, although it has similar profiles to Tepalcingo as regards international migration intensity indices, it is the municipality with the highest rate of Catholicism in the state.3 Selecting the two municipalities would make it possible to explore the reasons why the effects of international migration affect religious diversity in one case, while in the second municipality, they contribute to the revitalization of Catholicism.

It should be noted that while it is true that both municipalities are located towards the eastern limits of the state, despite their proximity, they fall into two distinct regions, due to both their ecological features and their historical formation. Moreover, in the case of Zacualpan, the historical presence of grass-roots communities and the charismatic movement within the local church has greater significance. In both cases, patron saints' day celebrations have greater regional visibility, the Lord of Tepalcingo and Our Lady of the Assumption being the main figures of worship respectively.

Analytical Axes

For the in-depth analysis, in addition to continuing to review the sociodemographic information available for selected localities, the ethnographic work was organized around participant observation, the identification of places of worship, conducting interviews with those responsible for each center of worship as well as in-depth interviews with key informants, including the founders of new religious congregations and return migrants. Likewise, the churches in each locality were georeferenced, with the date and circumstances of their formation being identified in each case.

Once the ethnographic work in selected municipalities had advanced, we continued with the analysis of the three specific axes of the relationship between migration and religion, around which the research was structured:

1. The effect of migration on religious pluralization, whether as a result of conversion processes, or the circulation of persons affiliated to different denominations.

2. The transnationalization of religious practices and the circulation of socio-cultural remittances linked to religious beliefs, practices and institutions.

3. The transformation of the perception of religious otherness -and the consequent attitudes of religious tolerance or intolerance- on the basis of the migration experience.

Below is a discussion of the main aspects of the methodological strategy used for the analysis of these three main axes.

The Relationship Between Migration and Religious Pluralization

Due to the importance of Catholicism in Mexico, both in terms of its volume and its historical presence, in previous studies, the authors of this paper used the decrease in the percentage of the population who professed Catholicism as the primary indicator of religious diversification. In general terms, until the 1990 census, the percentage points lost by Catholicism swelled the numbers of the "Protestant or evangelical"4 ranks and to a lesser extent, the group of people claiming not to profess any religion. Thus, from a broad time perspective, the percentage decrease of Catholicism was an indicator permitting the identification, at the national level, of the regions where religious change occurred fairly quickly. However, it offered very little information about who the new "non-Catholics" were.

The changes made to the questionnaire in the national population census from 2000 onwards helped advance the understanding of religious diversity in Mexico, providing categories that account more accurately for the growth of different denominations. In particular, this new classification distinguishes historical Protestantism from the new evangelical and the so-called "no evangelical biblical" denominations (Adventists, Jehovah's Witnesses and Mormons). Disaggregating the category of "Protestants and evangelicals" therefore made it possible to identify the various groups and their spatial distribution. But it also allowed the category of "Religious Diversity" to be constructed in a different way.

In particular, for the state of Morelos, since the 2000 Census, it has been possible to determine that in certain municipalities, the decrease of Catholicism is mainly reflected in the growth of a single "minority" religious denomination, while in other cases, there is simultaneous growth of more than one denomination. Thus, for example, whereas in municipalities such as Tlaltizapán, non-Catholic believers primarily identified themselves as Jehovah's Witnesses; in other cases, such as Tepalcingo, they were mainly divided among Pentecostals, Seventh-day Adventists and Jehovah's Witnesses. There was also a significant albeit smaller presence of historical Protestantism (especially Methodists) and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons). This diversity remained in 2010, with a predominance of evangelical denominations as the first minority (12 percent), followed by the category "No affiliation" (7 percent), and non-evangelical biblical denominations (4.5 percent).

In other words, a similar decrease in the percentage of non-Catholic believers resulted, in one case, in a context of majority religion (Catholicism) plus a single minority religious affiliation (M+m); where in other contexts, two or even three different categories with significant percentages (M+m1+m2 ...) were added to the majority religion.

Thus, we initially identified as "various municipalities" in the state of Morelos all those whose index of Catholic population was equal to or less than 78 percent5, while distinguishing between those who had at least two religious "minority" denominations with percentages equal to or greater than five percent.

During a second stage, through various visits to selected municipalities, localities with lower rates of Catholic affiliation were identified, and again, the cases where it was possible to identify more than one denomination with relevant participation among the non-Catholic population were identified. In the case of Tepalcingo, the locality of Zacapalco was identified, with a significant Pentecostal evangelical presence, together with a lower presence of various affiliations. Unlike Zacapalco, in the case of Ixtlilco el Grande, within the same municipality, the non-Catholic population was significantly more divided among various evangelical and non-evangelical biblical denominations, with a particularly significant presence of Adventists.

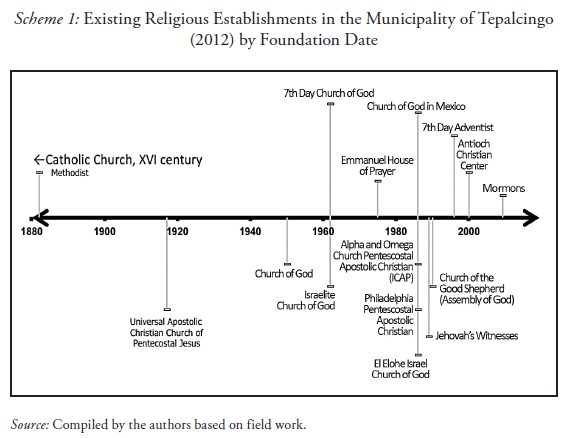

In order to determine the origin of religious diversity and chart its possible relationship to international migration, all the churches or temples were identified and subsequently interviews with the officials and congregants were used to identify the origin of each of the religious communities, identifying their origin and the participation of migrants in their founding and/or expansion. Thus, for the case of Tepalcingo, the following scheme was obtained:

Interestingly, in most existing churches or temples, no direct link was identified between the formation of religious communities and international migration. In most cases, new congregations emerged:

a) Due to regional proselytizing efforts

b) As a result of intra- or inter-regional migratory flows.

c) Due to divisions.

Only in one case, corresponding to Jehovah's Witnesses, were the two existing congregations formed by families or couples of return migrants. Although originally from Puebla, they first settled in the neighboring municipality of Axochiapan, where they immediately began to engage in proselitism in Tepalcingo, perceived as a place with greater openness to religious plurality. During this process, a key role was played by another return migrant, living in the neighboring municipality of Jonacatepec, who had spent over a decade proselytizing in the region.

Thus, regarding this point, it would appear that the impact of migration on religious diversification in Tepalcingo is relatively limited, or at least restricted to the growth of Jehovah's Witnesses. However, beyond the origin—or migratory experience—of those who founded the new religious congregations, it is important to note that the population of Tepalcingo is regarded as more open to diversity, by non-Catholic leaders themselves. As will be seen below, the migration experience, which entails more contact with religious diversity, appears to contribute, in the case of Tepalcingo, to this climate of greater tolerance.

There is also another area where it was possible to identify the importance of the migration experience to the United States for most of the religious leaders: regardless of the time or reason for religious conversion, the trajectories of non-Catholic leaders show that international migration is a key resource for the consolidation and expansion of new denominations. Migration as a resource can be observed through the contribution it means in terms of economic remittances, but even more than the latter, the sociocultural remittances that circulate with migrants are essential to the consolidation of new congregations: pastoral training and securing the employment and prestige acquired by belonging to transnational congregations, are among the most commonly mentioned factors. Thus, both circular and return migration are features that allow us to understand the internal dynamics of non-Catholic religious groups.

The following section contains a number of features showing how, as in Catholicism, it is possible to identify key transnational practices within the universe of non-Catholic denominations.

Sociocultural Remittances and Return Migration

As mentioned earlier, the localities studied form part of the so-called emerging migration regions, which confers certain specific characteristics on their migration dynamics. Among them, due to the fact that migratory intensification took place during the second quarter of the 20th century, it is now possible to identify, together with a significant flow of undocumented migrants, those who began their migration career prior to IRCA (Immigration Reform and Control Act), thereby managing to legalize their status. In the case of both Tepalcingo and Zacualpan, there is significant dispersal of destinations, meaning that although it is true that Morelos population travels through migrant networks accompanied by family and friends, consolidating these networks is problematic.6

The degree of geographic dispersion can be observed in Map 3, where the main places for issuing consular ID cards for migrants from Zacualpan are indicated. Although the most common destinations are located in traditional Mexican migration receiving regions (California, Chicago), it is also possible to identify a variety of new migration destinations (Minneapolis, Baltimore), where the presence of Mexican-origin population is still relatively small, and existing organizational forms poorly structured.

Moreover, reflecting their membership of an emerging migration region, circularity patterns tend to be less marked than in traditional sending regions, where there are a greater number of documented migrants who can cross the border on a regular basis, without having to face the dangers and high costs involved in illegal border crossing.

Interestingly, despite the lower circularity and dispersal of migration destinations, it is possible to identify the development of similar transnational links to those documented in previous studies undertaken in other localities (Espinosa, 2003; Rivera, 2006; Odgers and Ruiz, 2009; Morán-Quiroz, 2009; Fortuny, 2011). The difficulty of circularity is at least partially offset by the new communication technologies: there appears to be a certain virtual presence of migrants in their communities, either through the Internet or telephone calls. Return migration, whether voluntary, as part of a strategy or life project constructed on either side of the border, or involuntary, due to the stiffening of the ICE control and deportation mechanisms (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) is also important (Hirai, 2013; Alarcón, Escala, Odgers, 2013; Rivera, 2014).

For the specific case of Zacualpan, the extent and intensity of transnational practices linked to the religious sphere, are particularly visible in relation to the organization of the festival of the locality of Tlacotepec—largest locality in the municipality. Financial contributions sent by former inhabitants of this locality from the United States are essential for the success of the celebration. However, unlike what has been reported in studies on other localities, in the case of Tlacotepec—in the Municipality of Zacualpan—contributions from those who have had a successful career in internal migration, and even from believers born in other municipalities in the region are equally important. Another interesting contrast lies in the relatively low visibility of migrants during patron saints' day festivities: although those who, despite residing in the United States, have made major contributions are publicly thanked, there are no plaques or placards referring to the migrant community, a "Migrant Mass" is not celebrated, nor are there religious or cultural expressions—musical groups, processions, etcetera—referring to the participation of those living in the United States. It is even difficult to distinguish differences in the style of dress or consumption between locals and those who return, whether temporarily or permanently, for the patron saint's day festivities.

In the case of Tepalcingo, beyond the celebration of the patron saint's day feast, which is crucial to regional trade networks because of residents' participation in the second largest trade fair, linked to a nationwide religious celebration, it is interesting to note that transnational practices are important both in the evangelical and in the Seventh-day Adventist field, as borne out by the presence, for example, of transnationalized religious music groups. The consolidation of Adventists in these localities historically intersects with the beginning and rise of the international migration process in the mid-1980s, in both Ixtlilco El Grande and Zacapalco, and coincides precisely with the acceleration of international migration in sites located in the emerging region of Mexico-US migration. Pioneers of international migration in both localities in Tepalcingo are recognized as Seventh-day Adventists.

In 1985 two Adventist men, musicians from Ixtlilco, arranged with some Pentecostal preachers from Santa Cruz, Puebla, to travel to the United States for the purpose of taking mariachi music (Christian music) at a large convention held very near Los Angeles, California. They were assisted by the US Adventist Church in obtaining both passports and visas to enter the United States, which sent them personal invitations to make this trip possible. These two men returned to Ixtlilco, after touring several places in the United States, to which were invited after the end of the convention.

They traveled again in 1987, this time to the city of Dallas, Texas, guided once again by their Adventist brethren, but this time by those from Zacapalco, who had also engaged in international migration with the support of the church in order for them to preach, through the sale of Christian books, and with the facilities provided, of course, by having two pastors, from Zacapalco, who worked temporarily by teaching the gospel in Spanish in Dallas. They were the two brothers from Zacapalco who had gone to the University of Montemorelos a few years earlier to train and had subsequently been incorporated into pastoral work in the southern United States.

Thus, as of 1969, the presence was recorded of an Adventist pastor, originally from Zacapalco, who lived on the outskirts of the city of Dallas, Texas. This person contributed to the creation of an important node in the city, becoming a key contact for facilitating information and opening up the migration route from Zacapalco and Ixtlilco El Grande, and strengthening their regional interconnections, since by that time a number of inhabitants of Chinameca (a locality next to Zacapalco) had also taken the route to the North, supported by Pentecostal brothers from the Assemblies of God.

Thus the migratory route from Ixtlilco and Zacapalco to Texas, particularly Dallas7, was originally drawn on the basis of the Adventist movement. The repeated trips and circularity of the Mensajeros del Rey musicians between the localities of Tepalcingo and various places in the United States allowed them to know the routes and crossing points to begin the journey to the North and establish new contacts and enabled some of them to subsequently become guides or coyotes for ensuring people's safe passage, or transporting packages. Likewise, the invitation issued by the Zacapalco pastor, first to his relatives and then to other local residents, was certainly another key factor in opening up new routes and consolidating other US destinations. After Texas, some set off for California, near the counties of San José and Los Angeles, and later New York and Minneapolis, some of whom were supported by the inhabitants of the localities of Axochiapan, particularly Quebrantadero, to go to Minnesota.

The coming and going of people between the localities of Tepalcingo and Texas, supported by the Adventists, permitted the exchange of religious items, music, celebratory practices, but also medicinal herbs, clothing and subsequently prepared foods. This movement was possible, despite the fact that the majority of migrants from the locality of Ixtlilco are undocumented, because the members of the group of mariachi musicians had had tourist visas to enter the United States for over 30 years, and although they only stay there temporarily, nowadays, all the children of these musicians live in the US. Some have settled in Dallas and others in Minnesota and not all of them have immigration documents, yet some of them are now legal US residents.

Migratory religious networks did not necessarily have the effect of adding new members to the Adventist Church. Members of other religious groups also used these networks to migrate, but the Adventist network was certainly an effective network that led to a number of conversions before emigrating, or in the host society, and also contributed to reaffirming the religious affiliation of those who, as part of the community, were welcomed with accommodation the moment they arrived in Texas, and subsequently received assistance in securing employment. Some of the Adventists who traveled during the second half of the 1980s remarked that their first job had involved selling popsicles, driving through the streets with a refrigerated truck. Apparently this was one of the jobs they were able to obtain in Texas through contacts with the Adventist community.

The Mensajeros del Rey mariachi was a key agent in this process of transnationalizing Christian music composed and arranged in Ixtlilco El Grande, but also a nodal factor in the construction of other transnational links that are not necessarily confined to the religious sphere, expressed for example in the consolidation of the parcel service, which ever week moves significant amounts of packages by road between Ixtlilco, various locations in Puebla and Guerrero and the cities of Dallas and Minnesota.

The Perception of Diversity

As mentioned earlier, in the case of the municipalities studied, it is interesting to note that, despite the general characteristics of their migration—and the consequent construction of transnational links—there do not appear to be marked differences; the changes in the distribution of religious affiliations have followed divergent paths. Whereas Zacualpan, in addition to its high rate of allegiance to Catholicism (93.5 percent), continues to maintain the religious practice of traditional Catholicism linked to the celebration of the patron saints with great enthusiasm; Tepalcingo has seen a rapid pluralization that coexists with traditional Catholicism, reflected in the steady growth of affiliation to Protestant and evangelical (12 percent) and non-evangelical biblical denominations (4.5 percent), in addition to those who declare that they profess no religion (7 percent). This is even more remarkable if we consider their localities: in Ixtlilco El Grande, three religious groups were distributed, with relatively close percentages: Pentecostals and Neopentecostals (13.4 percent), followed by Seventh-day Adventists (10.9 percent) and other evangelicals (9.4 percent). Moreover one percent of the total declared that they were Jehovah's witnesses in a locality that has not yet built a facility for the Kingdom Hall. A significant proportion of the population declared that it professed no religion, accounting for 19.1 percent of the total. Incidentally, this is one of the categories that has experienced the greatest inter-census growth in the past three decades. Meanwhile, in Zacapalco, non-Catholics account for 41 percent of the total, whereas 38 percent declared they were Catholics, and 15.6 percent stated that they did not profess any religion (Inegi, 2010).

The question that arises, then, is: What explains the fact that, despite the geographical proximity between both municipalities and their insertion in similar migratory contexts, they underwent such different processes of religious change? As noted above, field research conducted in the region allows us to posit that the experience of migration constitutes an economic and sociocultural resource, which has made it possible to strengthen or accelerate processes of change that are already underway, but has not been crucial to determining the direction of these changes.

Thus, in the case of Tepalcingo, we observed that religious diversification processes are linked both to regional networks that existed incipiently prior to the processes of migratory intensification, and migration to the United States. Religious pluralization is concentrated in locations such as Zacapalco and Ixtlilco. In this respect, in addition to being found in the origin of certain non-Catholic congregations, international migration constitutes an additional resource for the development of new denominations and other religious congregations by providing economic resources, social capital and symbols of prestige for those who circulate. However, it should be stressed that in most of the cases identified—although not all—non-Catholic networks originated prior to migration and are linked to processes of regional changes. In other cases, certain non-Catholic religious groups have gained a degree of expertise in the care of the faithful, and their eventual expansion by focusing on providing support for young returnees with addiction problems, for example. Thus one effect of the migratory experience on the local-regional religious field is also associated with the development of other mechanisms of care/specialization and a diversified range of social services for the faithful, which could undoubtedly also be a result of the circulation of sociocultural remittances, particularly religious ones.

Meanwhile, in the municipality of Zacualpan, particularly in the locality of Tlacotepec, Catholicism linked to participation in patron saint's day celebrations—which reinforces the sense of belonging to the locality—is undoubtedly taken up by international migrants in the process of the construction of transnational links. Likewise, the flow of financial remittances enhances patron saint day celebrations and revitalizes the systems of responsibilities, where migrants find a resource for renegotiating the sense of belonging. However, there are other resources of local Catholicism that are crucial to understanding the low growth of non-Catholic denominations in the locality. Among others, we should mention two important aspects:

1. The historical importance of the system of religious cargos (responsibilities) linked to the organization of the ejido farm work, which remains relevant locally.

2. The subsistence of certain grass-roots communities founded in the third quarter of the last century, under the influence of liberation theology, which testify to the uniqueness of the local brand of Catholicism8.

However, despite the different trends in the two cases studied, there is a shared process of change, linked to the increased contact with religious diversity that arises from the migration experience, even for those who continue to identify themselves as Catholics.

Although it is necessary to continue review the ethnographic material to advance in this direction, this section concludes by mentioning the experience of Aurora, a native of Tlacotepec, in the municipality of Zacualpan, because she is a significant case in this regard.

Aurora traveled to the United States without immigration papers, together with her two young children. A few months after her arrival, the adversities she faced led her to temporarily reside first in a Salvation Army hostel and then in a women's shelter run by the Methodist church. Later, in her search for support given her extremely precarious situation, Aurora and her children approached the Mormon community.

On each occasion, she and her children approached the religious communities of their protectors, participating in various services. Finally, after various vicissitudes, Aurora and her eldest son returned to Zacualpan.

On her return, Aurora went back to the local parish, considering that in the last analysis, she had never ceased to be Catholic. However, both the migration experience and her contact with other religious denominations had turned her into an unconventional believer, unwilling to adhere to the strict behavioral codes in her locality.

A few months after her return, the conflicts she experienced with other members of the parish, especially with some of the non-migrant women in the community, made her feel uncomfortable in it. She therefore decided to remain a believer and identify herself as Catholic, while shifting religious practice to the individual level. In this regard, Aurora appears to follow the logic of believing without belonging (Davie, 1994).

Meanwhile, on his return, Donato, Aurora's son, who lives with her, decided that a Pentecostal evangelical church in the village was the closest he could find to his way of being a believer and practicing religion. For several months, he was fully integrated into the evangelical community, becoming greatly appreciated by the congregants. Later on, however, due to a personal conflict with the pastor, he was forced to leave the congregation.

At present, Donato believes that, due to his experience in the United States, where he found out about various religions, he is now able to distinguish between the good and bad in every religion and has therefore decided to create his own form of believing and practicing. Thus, although he identifies himself as Christian, Donato's case is a good example, within the evangelical world, of being a believer "my way" (Parker, 2005).

Conclusions

The project "Mudar de credo en contextos migratorios" (changing creed in migration contexts) allowed us to advance the reflection on the relationship between religion and migration, from two main points of view. First, the methodological design required reflecting on the analytical categories and research strategies required for the study of this relationship in the Mexican context. Moreover, in light of the results obtained, it is possible to identify some of the empirical expressions acquired by this relationship more accurately.

Specifically, the review of existing statistical information was essential to identifying various configurations of the relationship between migration intensity and religious diversity. While geo-referenced statistical analysis does not establish causality, it does enable one to identify major regional trends, and identify contexts that appear to be an exception.

Field research9 in the selected municipalities on the basis of statistical information made it possible to build three analytical axes of the relationship between migration and religious change. This includes: the possible impact of migration on religious pluralization processes; the transnationalization of religious practices—and sociocultural remittance flows—and the transformation of relations with religious otherness.

While it is necessary to continue the analysis of the empirical data compiled in Tepalcingo and Zacualpan, it is already possible to advance a number of conclusions based on the research of the three areas mentioned above in these two different contexts.

First of all is the fact that international migration fails to trigger the establishment of non-Catholic churches in the localities studied. In short, we can argue that, although the experience of international migration allows migrants to obtain the financial and symbolic resources essential for the strengthening and expansion of new religious congregations, historically, the process of religious pluralization began before the intensification of international migration, shaping the local and regional contexts in which religious change acquired different nuances. Thus, both traditional religious practices and the development of religious communities of other denominations may be influenced by the intensification of migration and the participation of its members. However, migration does not determine the direction religious change will take.

In this respect, in the two municipalities studied, the authors noted that, despite the absence of classic circular migration patterns, migratory intensification, and subsequently the returns—whether voluntary or forced—to their places of origin, has led to the circulation of sociocultural remittances and the transnationalization of certain religious practices. This is true in both the world of traditional Catholicism, and in the old and new religious denominations in the region.

Conversely, the transformation of the perception of religious diversity does seem to be a relevant characteristic among some of the people who at some point in their lives decided to travel north. Thus, regardless of their identification with Catholicism, or an evangelical or non-evangelical biblical denomination, among some migrant returnees we observed a new way of understanding and practicing their religious beliefs as well as other ways of relating to those who practice other faiths. The implications that these new ways of being believers will have in the contexts of origin are some of the topics for discussion that should continue to be explored.

References

ALARCÓN, Rafael; Luis ESCALA and Olga ODGERS, 2013, Mudando el hogar al Norte: Trayectorias de integración de los inmigrantes mexicanos en Los Ángeles, Tijuana, Mexico, El Colef. [ Links ]

BOBES, Velia, 2011, Los tecuanes danzan en la nieve. Contactos transnacionales entre Axochiapan y Minnesota, Mexico City, Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales. [ Links ]

CADGE, Wendy and Elaine H. ECKLUND, 2007, "Immigration and Religion", Annual Review of Sociology, Palo Alto, United States, Social Sciences Citation Index, Vol. 33, pp. 359–379. [ Links ]

CONSEJO NACIONAL DE POBLACIÓN (CONAPO), 2010, Índices de intensidad migratoria. México-Estados Unidos a nivel nacional, Mexico City, Conapo, at <http://www.conapo.gob.mx/work/models/CONAPO/intensidad_migratoria/anexos/Anexo_A.pdf>, accesed on May 25, 2013. [ Links ]

DAVIE, Grace, 1994, Religion in Britain since 1945: Believing without Belonging, Oxford, United Kingdom, Blackwell. [ Links ]

DIEHL, Claudia and Matthias KOENIG, 2009, "Religiosity and Gender Equality: Comparing Natives and Muslim Migrants in Germany", Ethnic and Racial Studies, London, Routledge, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 278–301. [ Links ]

ESPINOSA, Víctor, 2003, "El día del emigrante y el regreso del Purgatorio: Iglesia, migración a los Estados Unidos y cambio sociocultural en un pueblo de Los Altos de Jalisco", Estudios Sociológicos, Mexico City, El Colegio de México, Vol. 15, No. 50, pp. 375–418. [ Links ]

FORTUNY, Patricia, 2011, "Iglesias católicas multiétnicas en nuevos destinos: Análisis comparativo", in Alberto Hernández, coord., Nuevos caminos de la fe. Prácticas y creencias al margen institucional, Tijuana, Mexico, El Colef, pp. 291–322. [ Links ]

GAMIO, Manuel, 1971 [1930], Mexican Immigration to the United States. A Study of Human Migration and Adjustment, New York, Dover/University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

GLICK SCHILLER, Nina; Ayse CAGLAR and Thaddeus GULDBRANDSEN, 2006, "Beyond the Ethnic Lens: Locality, Globality, and Born-Again Incorporation", American Ethnologist, United States, American Ethnological Society, Vol. 33, No. 4, pp. 612–633. [ Links ]

HAGAN, Jacqueline, 2008, Migration Miracle: Faith, Hope and Meaning on the Undocumented Journey, Cambridge, United States, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

HERBERG, Will, 1983 [1955], Catholic, Protestant, Jew. An Essay in American Religious Sociology, Chicago, University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

HIRAI, Shinji, 2010, "Migración y 'redes' transnacionales: El caso de las prácticas religiosas de los migrantes mexicanos en California", in Alex Munguía Salazar and Gustavo López Ángel, coords., Migración, derechos humanos, religión y política, Puebla, Mexico, BUAP/Montiel & Soriano, pp. 37–57. [ Links ]

HIRAI, Shinji, 2013, "Formas de regresar al terruño en el transnacionalismo: Apuntes teóricos sobre la migración de retorno", Alteridades, Mexico City, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Unidad Iztapalapa, Vol. 23, No. 45, January–June, pp. 95–105. [ Links ]

HIRSCHMAN, Charles, 2004, "The Role of Religion in the Origins and Adaptation of Immigrant Groups in the United States", International Migration Review, New York, Center for Migration Studies, Vol. 38, No. 3, pp. 1206-1233. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTADÍSTICA, GEOGRAFÍA E INFORMÁTICA (INEGI), 2000, Censo General de Población y Vivienda, 2000, Mexico City, Inegi, at <http://www.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/olap/proyectos/bd/consulta.asp?c=10252&p=14048&s=est>, accesed on May 28, 2013. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTADÍSTICA Y GEOGRAFÍA (INEGI), 2010, Censo General de Población y Vivienda, 2010, Mexico City, Inegi, at <http://www.censo2010.org.mx/>, accesed on May 27, 2013. [ Links ]

KURTZ, Lester, 1995, Gods in the Global Village. The World´s Religions in Sociological Perspective, Thousand Oaks, United States, Pine Forge Press. [ Links ]

LEVITT, Peggy, 2009, God Needs no Passport. Immigrants and the Changing American Religious Landscape, New York, The New Press. [ Links ]

LEVITT, Peggy, 2011, "A Transnational Gaze", Migraciones Internacionales, Tijuana, Mexico, El Colef, Vol. 6, No. 1, January–June, pp. 9–44. [ Links ]

LEVITT, Peggy, 2012, "Religion on the Move: Mapping Global Cultural Production and Consumption", in Wendy Cadge, Peggy Levitt and David Smilde, edits., Religion on the Edge: De-Centering and Re-Centering the Sociology of Religion, Oxford, United Kingdom, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

MORÁN-QUIROZ, Luis Rodolfo, 2009, "Devociones populares y comunidades transnacionales", in Olga Odgers Ortiz and Juan Carlos Ruiz Guadalajara, coords., Migración y creencias. Pensar las religiones en tiempos de movilidad, Tijuana, Mexico, El Colef/El Colegio de San Luis/Miguel Ángel Porrúa. [ Links ]

ODGERS ORTIZ, Olga, 2008, "Construcción del espacio y religión en la experiencia de la movilidad. Los Santos Patronos como vínculos espaciales en la migración México/ Estados Unidos", Migraciones Internacionales, Tijuana, Mexico, El Colef, Vol. 4, No. 3, January–June, pp. 5–26. [ Links ]

ODGERS ORTIZ, Olga and Carolina RIVERA, 2007, "Movilidad y adscripciones religiosas", in Renée de la Torre and Cristina Gutiérrez, coords., Atlas de la diversidad religiosa en México, Mexico, El Colef/CIESAS/Conacyt/Segob. [ Links ]

ODGERS ORTIZ, Olga and Juan Carlos RUIZ GUADALAJARA, 2009, coords., Migración y creencias, pensar las religiones en tiempos de movilidad, Mexico, Miguel Ángel Porrúa/El Colef. [ Links ]

ORSI, Robert, 1999, Gods of the City. Religion and the American Urban Landscape, Bloomington, United States, Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

PARKER GUMUCIO, Cristián, 2005, "América Latina ya no es católica? Pluralismo religioso y cultural creciente", América Latina Hoy: Revista de Ciencias Sociales, Salamanca, Spain, Instituto de Iberoamérica/Universidad de Salamanca, Vol. 41, pp. 35–56. [ Links ]

RIVERA SÁNCHEZ, Liliana, 2006, "Cuando los Santos también migran. Conflictos transnacionales por el espacio y la pertenencia", Migraciones Internacionales, Tijuana, Mexico, El Colef, Vol. 3, No. 4, July–December, pp. 35–59. [ Links ]

RIVERA SÁNCHEZ, Liliana, 2014, "Reinserción social y laboral de inmigrantes retornados de Estados Unidos en un contexto urbano", Iztapalapa. Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, Mexico City, UAM-I, No. 75, Year 34, July–December, pp. 29–56. [ Links ]

RIVERA SÁNCHEZ, Liliana and Fernando LOZANO ASCENCIO, 2006, "Los contextos de salida urbanos y rurales y la organización social de la migración", Migración y Desarrollo, No. 6, pp. 45–78. [ Links ]

RIVERA-SÁNCHEZ, Liliana; Olga ODGERS-ORTIZ and Alberto HERNÁNDEZ, 2014, "La migración internacional y la diversificación religiosa en Morelos. Una mirada sociodemográfica", Papeles de Población, Vol. 20, No. 80, April–June, pp. 47–85. [ Links ]

SASSEN, Saskia, 1991, The Global City, New York/London/Tokyo/Princeton, Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

TUIRÁN, Rodolfo; Carlos FUENTES and José Luis ÁVILA, 2002, Índice de intensidad migratoria México-Estados Unidos 2000, México, D. F., Conapo. [ Links ]

WARNER, Stephen, 1993, "Work in Progress towards a New Paradigm for the Study of Religion in the United States", American Journal of Sociology, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, Vol. 98, No. 5, pp. 1044–1093. [ Links ]

WARNER, Stephen and Judith WITTNER, 1998, Gatherings in Diaspora. Religious Communities and the New Immigration, Philadelphia, United States, Temple University Press. [ Links ]

* Text and quotations originally written in Spanish.

1 Interinstitutional research project, conducted between 2003 and 2007 with financing from the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (Conacyt) (U42863-S).

2 The Migration Intensity Index prepared by the National Population Council (Conapo) is used. Four main factors in this index are considered: number of emigrants, circular migration, return migration and remittance household receipts (Conapo, 2010).

3 The municipalities of Axochiapan and Mazatepec were also initially considered. In Mazatepec, a highly significant relationship of convergence had been identified between international migration and religious diversification (Rivera and Lozano, 2006). However, for various reasons, including insecurity in some of the locations visited, work focused specifically on one locality in Zacualpan, Tlacotepec, and three localities in Tepalcingo, the municipal head town, Ixtlilco El Grande and Zacapalco.

4 Until 1990, national population censuses only distinguished Catholics from "Protestants or evangelicals," "Israelites," and those who claimed to profess "another religion" or "none." For detailed information on their historical development over the past seventy years, see Rivera-Sánchez, Odgers-Ortiz and Hernández, 2014.

5 Classification ranges were established by the natural breaks derived from census data georeferencing the Catholic population at the municipal level.

6 However, nowadays it is possible to identify some more established migration networks and certain destination areas characteristic of Morelos migrants in the United States, such as Minnesota for the population of Axochiapan. This municipality, located on the border with the state of Puebla, is a relatively recent source of migration or rather its massification corresponds to the last decade of the last century (Bobes, 2011).

7 This is one of the preferred destinations of immigrants from Tepalcingo, the head town, and Zacapalco, but mainly from Ixtlilco El Grande.

8 As an important feature of the current Catholicism in the head town municipality of Zacualpan, it is also useful to note the work of the local priest, a dynamic young man, who graduated from the Faculty of Political and Social Sciences of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), who has attempted to establish links with the community, particularly with young people.

9 During the ethnographic work interviews, in-depth interviews and semi-structured interviews were conducted with both leaders of congregations and religious groups and members of their communities. Likewise, a survey was conducted in non-Catholic religious establishments, specifically in the three localities of Tepalcingo and the locality of Tlacotepec, in the municipality of Zacualpan de Amilpas.

INFORMACIÓN SOBRE LOS AUTORES

OLGA ODGERS ORTIZ es doctora en Sociología por la Escuela de Altos Estudios en Ciencias Sociales (EHESS), París, Francia. Es investigadora adscrita al Departamento de Estudios Sociales de El Colegio de la Frontera Norte. Sus líneas de investigación se centran en el estudio de la relación entre migración, salud y religión. Entre sus publicaciones recientes se encuentran los artículos "La migración internacional y la diversificación religiosa en Morelos. Una mirada sociodemográfica", en Papeles de población (2014, con Rivera y Hernández); "Estado laico y alternativas terapéuticas religiosas. El caso de México en la atención de adicciones", en Debates do NER (en prensa, con Galaviz); y "Prácticas devocionales y construcción del espacio en la movilidad", en Alteridades (2014, con Calderón Bony); así como el libro Mudando el hogar al norte. Trayectorias de integración de los inmigrantes mexicanos en Los Ángeles (El Colef, 2012, con Alarcón y Escala).

LILIANA RIVERA SÁNCHEZ es doctora en Sociología por The New School for Social Research, Nueva York; maestra en Ciencias Sociales por la Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, sede en México, y licenciada en sociología por la Universidad Veracruzana. Actualmente es profesora-investigadora en el Centro de Estudios Sociológicos de El Colegio de México. Sus áreas de interés se vinculan con el estudio de las movilidades en espacios urbanos; la formación de circuitos migratorios contemporáneos y las prácticas religiosas y culturales en contextos de movilidad. Dos de sus publicaciones recientes son: Vínculos y prácticas de interconexión en un circuito migratorio entre México y Nueva York (Buenos Aires, Clacso, 2012); y The Practice of Research on Migration and Mobilities (Londres, Springer, 2014).

ALBERTO HERNÁNDEZ HERNÁNDEZ es doctor en Sociología por la Universidad Complutense de Madrid; realizó estudios de maestría y licenciatura en Sociología en la Facultad de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Actualmente es profesor-investigador adscrito al Departamento de Estudios de Administración Pública en El Colegio de la Frontera Norte (El Colef). De 2007 a 2014 fue Secretario de Planeación y Desarrollo Institucional en El Colef. Miembro del Sistema Nacional de Creadores (SNI), nivel III. Entre sus más recientes publicaciones se encuentran Frontera Norte: Escenarios de la diversidad religiosa (Colef/Colmich, 2013); Nuevos caminos de la fe: Prácticas y creencias al margen institucional (coord., Colef/UANL/Colmich, 2011); Regiones y religiones en México. Estudios de la transformación sociorreligiosa (con Carolina Rivera, coords., El Colef/Ciesas/Colmich, 2009).