1. Introduction

Although Northern Mexico presents extensive areas with sediments of numerous paleolakes that covered the region during the late Quaternary, only a few sites have been studied for their fossil remains. Nevertheless, more studies have been carried out recently, especially from the paleolakes of the Chihuahuan and Sonoran Deserts with species-rich molluscan assemblages (Catto and Bachhuber, 2000; Czaja et al., 2014a, 2014b).

We present a new assemblage of terrestrial and freshwater malacofauna located at the southern portion of the state of Coahuila in northern Mexico. The study area is located among farmlands at Rancho Buena Fe, called the El Molino Mammoth site, approximately 4 km east of the city of Parras de la Fuente (Figure 1). The locality was described in detail by Miller et al. (2008) and consists of an abandoned well site approximately eight meters deep by 6 meters wide, excavated in the year 2000 (25° 25’54.8” N, 102° 08’56.52” W; Elevation 1,530 m) (Figures 2a and 2b). The same authors carried out a Carbon14 dating of the basal sediments of the cross section which yielded an age of 11,740 ± 50 years B.P. (Late Pleistocene). The macrofauna remains found at the site included mammoth (Mammuthus columbi), horse (Equus ssp.), camels (Camelops cf. hesternus) and several small mammal remains (Miller et al., 2008). During the last few years, partial collapses within the well have buried the Late Pleistocene sediments, making them inaccessible for sampling.

Figure 1 Location of the abandoned well at the El Molino Mammoth site in Rancho Buena Fe, Parras, Coahuila, Mexico.

Figure 2 a. The El Molino Mammoth sites abandoned well in present-day Rancho Buena Fe; b. Image of the abandoned well from the year 2000 excavation; c. Geological profile of the Holocene strata sampling points. Black dash lines represent the start of the D strata. Image b is modified from Miller et al. (2008).

This paper focuses on reporting new Late Pleistocene and Holocene records of a continental malacofauna assemblage from the El Molino Mammoth site in Rancho Buena Fe, Parras, Coahuila, as well as to propose additional information on the environmental changes during the Pleistocene-Holocene transition.

2. Materials and methods

Because of the collapsed basal part of the geological strata, Late Pleistocene sediments could not be sampled for this study. However, we used the sediments remaining from the mammoth excavation in 2000, which were stored at the laboratory of Paleontology of the Museo del Desierto in Saltillo, Coahuila, Mexico.

At the site, five 1 kg sediment samples were collected from the 3.30 m Holocene strata currently exposed within the abandoned well (Figure 2c). Samples from the C and D strata correspond to the Late Pleistocene-Holocene transition, while the remaining B1, B2 and A samples belong to the Holocene (Miller et al., 2008). The samples were screened through two sieves with 0.5 mm and 0.3 mm mesh sizes. The selection of mollusks was carried out under a stereoscopic microscope, and subsequently washed with 3% hydrogen peroxide in order to remove mud or any other organic residue. All shells were photographed with a Zeiss AxioCam ERc 5s camera attached to a Zeiss Stemi 2000-C microscope. Mollusk identifications are based on Pilsbry (1946, 1948), Leonard (1950, 1952), Metcalf and Smartt (1997), Nekola (2004), Wethington et al. (2009), Nekola and Coles (2010), and Walther et al. (2010). The revision was based mainly on biodiversity websites including WoRMS (World Register of Marine Species), and MolluscaBase (MolluscaBase, 2021). The material is part of the University Juárez Malacological Collection (UJMC) and is housed at the Faculty of Biological Science of the Juarez State University of Durango (UJED).

3. Results

The studied material comprises a total of 19 mollusk taxa belonging to 15 families and 17 genera. Mollusks found within the Late Pleistocene strata include 14 species belonging to 12 families and 14 genera, while the Holocene strata includes 10 species (8 families and 9 genera) (Table 1).

Table 1 Taxonomic list of Late Pleistocene and Holocene malacofauna from the El Molino Mammoth site in Rancho Buena Fe, Parras, Coahuila.

| Family | Genus | Species | Late Pleistocene |

Holocene |

| Bivalves | ||||

| Sphaeriidae | Euglesa | E. compressa | x | |

| E. casertana | x | |||

| Aquatic | ||||

| Lymnaeidae | Galba | G. humilis | x | |

| G. obrussa | x | x | ||

| Physidae | Physella | P. acuta | x | |

| Planorbidae | Gyraulus | G. parvus | x | |

| Ferrissia | F. californica | x | ||

| Terrestrial | ||||

| Ellobiidae | Carychium | exiguum | x | |

| Succineidae | Succinea | Succinea sp. | x | x |

| Cochlicopidae | Cochlicopa | C. lubrica | x | |

| Gastrocoptidae | Gastrocopta | G. cristata | x | |

| G. tappaniana | x | |||

| Pupillidae | Pupilla | P. hebes | x | |

| Valloniidae | Vallonia | V. gracilicosta | x | |

| Gastrodontidae | Zonitoides | Z. arboreus | x | x |

| Glyphyalinia | G. indentata | x | x | |

| Euconulidae | Habroconus | Habroconus sp. | x | |

| Pristilomatidae | Hawaiia | H. minuscula | x | |

| Agriolimacidae | Deroceras | D. laeve | x | x |

3.1. SYSTEMATIC DESCRIPTIONS

Bivalvia Linnaeus, 1758

Family Sphaeriidae Deshayes, 1855

Genus Euglesa Jenyns, 1832

Euglesa casertana (Poli, 1791)

Figure 3 a. Deroceras laeve; b. Galba humilis; c. Ferrissia californica; d. Physella acuta; e. Gyraulus parvus; f. Galba obrussa; g. Carychium exiguum; h. Hawaiia minuscula; i. Euglesa compressa; j. Euglesa casertana. Scale bars = 2 mm.

Ecology: Perennial and ephemeral swamp ponds, streams, rivers and lakes (Herrington, 1962).

Current distribution: United States, Mexico, Cuba, Puerto Rico and from Honduras to Patagonia (Herrington, 1962).

Stratigraphic remarks: The stratigraphic distribution of E. casertana at the El Molino Mammoth site is limited to the A strata belonging to the Holocene. This species has also been found in a Late Pleistocene site of San Luis Potosí, Mexico (Arroyo-Cabrales et al., 2008).

Referred material: UJMC 600, 18 specimens.

Measurements: Length: 2.2 mm; diameter: 3 mm.

Euglesa compressa (Prime, 1852)

Ecology: E. compressa is restricted to areas of permanent water, preferring shallow sandy bottoms and rooted vegetation (Czaja et al., 2014b).

Current distribution: Canada and United States. In Mexico it can be found in Chihuahua, Coahuila and Tamaulipas (Burch, 1972; Bequaert and Miller, 1973).

Stratigraphic remarks: The stratigraphic distribution of E. compressa at the El Molino Mammoth site is limited to Late Pleistocene strata. The first Pleistocene record for this species in Mexico was reported by Czaja et al. (2014b) from paleolake Irritila, Coahuila, northern Mexico.

Referred material: UJMC 601, 44 specimens.

Measurements: Length: 4 mm; diameter: 5 mm.

Gastropoda Cuvier, 1795

Family Lymnaeidae Rafinesque, 1815

Genus Galba Schranck, 1803

Galba humilis (Say, 1822)

(Figure 3b)

Ecology: This semi-aquatic species preferers muddy areas along the edges of creeks, lakes, ponds, and swamps (Clarke, 1981; Stewart and Dillon, 2004).

Current distribution: North America. Mexican states of Chihuahua, Coahuila, Hidalgo, Nuevo León, Sonora and Tamaulipas (Mazzotti, 1956; Landeros et al., 1981; Thompson, 1999; Thorp and Rogers, 2016).

Stratigraphic remarks: At the El Molino Mammoth site, the stratigraphic distribution of G. humilis is limited to the Holocene A strata. Galba humilis is widely known with its synonymous name, Lymnaea humilis.

Referred material: UJMC 602, 14 specimens.

Measurements: Height: 8.5 mm; aperture length: 4 mm.

Galba obrussa (Say, 1825)

Ecology: Galba obrussa is common along the edges of small bodies of water such as streams and ponds, preferring areas along river banks or under protected spots (Baker, 1928; Miller, 1966).

Current distribution: From the Atlantic to the Pacific. From Canada to the southern state of Arizona and into northern Mexico, including the states of Durango and Coahuila (Baker, 1928; Mazzotti, 1955; Naranjo-Garcia, 2010).

Stratigraphic remarks: The stratigraphic distribution of G. obrussa at the El Molino Mammoth site ranged from the Late Pleistocene up to the Holocene D strata. This species was formerly known and described as Fossaria obrussa. This is the first Pleistocene record of this species in Coahuila, previously known only from a Late Pleistocene locality within the Valsequillo basin of central Mexico (Stevens et al., 2012).

Referred material: UJMC 603-604, 11 specimens (Late Pleistocene: 7; Holocene: 4).

Measurements: Height: 4 mm; aperture length: 1.90 mm.

Family Physidae Fitzinger, 1833

Genus Physella Haldeman, 1842

Physella acuta (Draparnaud, 1805)

Ecology: Physella acuta populations can be found in ponds, reservoirs, and the margins of rivers and streams, especially in disturbed sediments or disturbed areas rich in organic material environments (Wethington et al., 2009).

Current distribution: Cosmopolitan, can be found across six continents due to their high expansiveness by natural processes and accidental dispersal mediated by humans during the transport of exotic plants to Europe. In Mexico, the species is reported from Coahuila, Durango, Puebla, Aguascalientes, Veracruz and Michoacán (Arroyo-Cabrales et al., 2008; Wethington et al., 2009; Vinarski, 2017; Spyra et al., 2019; Czaja et al., 2020).

Stratigraphic remarks: The stratigraphic distribution of P. acuta at the El Molino Mammoth site is limited to the A strata (Holocene). Holocene and Pleistocene records for this species are known from Coahuila and Mexico City (Arroyo-Cabrales et al., 2008; Czaja et al., 2014a, 2014b).

Referred material: UJMC 605, 14 specimens.

Measurements: Height: 5.1 mm; aperture length: 3.85 mm.

Family Planorbidae Rafinesque, 1815

Genus Gyraulus Charpentier, 1837

Gyraulus parvus (Say, 1817)

Ecology: Gyraulus parvus is usually associated with abundant vegetation in shallow water (Tuthill et al., 1964).

Current distribution: North America. The species distribution in Mexico includes Durango, Morelos, Puebla and Sonora (Arroyo-Cabrales et al., 2008; Thompson, 2011; Czaja et al., 2020).

Stratigraphic remarks: At the El Molino Mammoth site, the stratigraphic distribution of G. parvus is limited to Late Pleistocene strata. This is the first record of G. parvus for the Pleistocene of Coahuila. This species has also been reported from other Late Pleistocene localities of central Mexico (Arroyo-Cabrales et al., 2008) and southern Mexico (Guerrero-Arenas et al., 2013).

Referred material: UJMC 606, 33 specimens.

Measurements: Diameter: 4.8 mm.

Genus Ferrissia Walker, 1903

Ferrissia californica (Rowell, 1863)

Ecology: Ferrissia californica can be found in small bodies of water, often capable of surviving dry conditions (Walther et al., 2010).

Current distribution: Members of the gastropod genus Ferrissia have a near-cosmopolitan distribution (Walther et al., 2010).

Stratigraphic remarks: The stratigraphic distribution of F. californica at the El Molino Mammoth site is limited to Late Pleistocene strata. F. californica has also been found in Pleistocene and Holocene localities within the state of Coahuila (Czaja et al., 2014a, b).

Referred material: UJMC 607, 5 specimens.

Measurements: Height: 1.2 mm; length: 2.8 mm.

Family Ellobiidae Pfeiffer, 1854

Genus Carychium Müller, 1773

Carychium exiguum (Say, 1822)

Ecology: Carychium exiguum inhabits humid environments such as swampy areas, is strongly hygrophilous and usually found under fallen leaves rocks and logs not far from water (Branson, 1961).

Current distribution: Canada, Colorado, New Mexico and Alabama, and Nuevo León in Mexico (Hubricht, 1985; Contreras-Arquieta, 1995).

Stratigraphic remarks: At the El Molino Mammoth site, the stratigraphic distribution of C. exiguum is limited to Late Pleistocene strata. This is the first Pleistocene record of this species from Coahuila. Arroyo-Cabrales et al. (2008) recorded C. exiguum from a Late Pleistocene locality of San Luis Potosí.

Referred material: UJMC 608, +100 specimens.

Measurements: Height: 2 mm.

Family Succineidae Beck, 1837

Genus Succinea Draparnaud, 1801

Succinea sp.

Figure 4 a. Cochlicopa lubrica; b. Glyphyalinia indentata; c. Succinea sp.; d. Gastrocopta cristata; e. Zonitoides arboreus; f. Habroconus sp.; g. Pupilla hebes; h. Gastrocopta tappaniana; i. Vallonia gracilicosta. Scale bars = 2 mm.

Ecology: Members of the Family Succineidae can be found in disturbed areas but prefers freshwater habitats with humid conditions among rocks, logs or leaf litter (Forsyth, 2005).

Current distribution: The Succineidae Family in Mexico is found distributed in Baja California, Central Mexico, Tamaulipas and Veracruz (Naranjo-García and Fahy, 2010).

Stratigraphic remarks: Late Pleistocene and the Holocene A, B1 and D strata. Late Pleistocene records in Mexico include Villa Acuña, Coahuila and Rancho La Amapola, San Luis Potosí (Arroyo-Cabrales et al., 2008).

Referred material: UJMC 609-610, 62 specimens (Late Pleistocene: 18; Holocene: 44).

Measurements: Height: 5.5 mm; aperture length: 3 mm.

Family Cochlicopidae Pilsbry, 1900

Genus Cochlicopa Férussac, 1821

Cochlicopa lubrica (O.F. Müller, 1774)

Ecology: Cochlicopa lubrica is considered a woodland mollusk and is usually found in forested montane habitats among damp under leaves (Judd, 1963; Kolb et al., 1975; Metcalf and Smartt, 1997).

Current distribution: The genus Cochlicopa contains a single Mexican species, C. lubrica, which inhabits northwest Chihuahua, southern Nuevo León and Durango (Pilsbry, 1953; Bequaert and Miller, 1973; Contreras-Arquieta, 1995; Correa-Sandoval, 2003; Naranjo-García and Fahy, 2010).

Stratigraphic remarks: The stratigraphic distribution of C. lubrica at the El Molino Mammoth site is limited to Late Pleistocene strata. Fossil records include sites in Coahuila and the Grava Valsequillo Formation of Puebla (Arroyo-Cabrales et al., 2008).

Referred material: UJMC 611, 2 specimens.

Measurements: Height: 6.5 mm; aperture length: 2.1 mm.

Family Gastrocoptidae Pilsbry, 1918

Genus Gastrocopta Wollaston, 1878

Gastrocopta cristata (Pilsbry and Vanatta, 1900)

Ecology: Gastrocopta cristata is found in wooded slopes near streams and under fallen logs, as well as in grass where moisture conditions are favorable and stable (Leonard, 1950).

Current distribution: Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas to western New Mexico and Arizona. In Mexico it is reported from Sonora (Leonard, 1950; Bequaert and Miller, 1973).

Stratigraphic remarks: At the El Molino Mammoth site, the stratigraphic distribution of G. cristata includes the entire Holocene strata. This species has only been recorded in Late Pleistocene deposits from Rancho La Amapola, San Luis Potosí (Arroyo-Cabrales et al., 2008).

Referred material: UJMC 612, +100 specimens.

Measurements: Height: 3 mm.

Gastrocopta tappaniana (C.B. Adams, 1841)

Ecology: G. tappaniana is a hydrophilic species observed in grasslands, lowland forests, wooded slopes and flood plains with poor drainage, usually among leaf litter and below logs and stones (Leonard, 1950; Branson, 1961; Nekola, 2004).

Current distribution: Arizona, New Mexico, Kansas, South Dakota in the United States and Alberta and Manitoba in Canada (Pilsbry, 1948). Not reported from Mexico.

Stratigraphic remarks: The stratigraphic distribution of G. tappaniana at the El Molino Mammoth site is limited to Late Pleistocene strata. This is the first fossil record of this species in Mexico.

Referred material: UJMC 613, 23 specimens.

Measurements: Height: 2.8 mm.

Family Pupillidae Turton, 1831

Genus Pupilla Fleming, 1828

Pupilla hebes (Ancey, 1881)

Ecology: Pupilla hebes can be found in forested mountain habitats consisting of wet meadows (Metcalf and Smartt, 1997).

Current distribution: The species has been reported in the United States from various localities of the western mountains, except in California. In Mexico, it has been found in Chihuahua and Baja California (Metcalf and Smartt, 1997; Miller, 1981).

Stratigraphic remarks: At the El Molino Mammoth site, the stratigraphic distribution of P. hebes is limited to Late Pleistocene strata. This is the first fossil record of this species in Mexico.

Referred material: UJMC 614, 9 specimens.

Measurements: Height: 3.1 mm.

Family Valloniidae Morse, 1864

Genus Vallonia Risso 1826

Vallonia gracilicosta Reinhardt, 1883

Ecology: Common under bushes protected spots such as under litter, rocks and dead grass. It is not restricted to a wooded habitat and can tolerate dry conditions (Kolb et al., 1975; Metcalf and Smartt, 1997).

Current distribution: Oklahoma, New Mexico and adjacent states. In Mexico, it is recorded only in Nuevo León (Metcalf and Smartt, 1997; Correa-Sandoval, 2003).

Stratigraphic remarks: The stratigraphic distribution of V. gracilicosta at the El Molino Mammoth site is limited to Late Pleistocene strata. Arroyo-Cabrales et al. (2008), recorded V. gracilicosta in two Pleistocene localities in Mexico, one near the municipality of Villa Acuna in Coahuila and the other at Rancho La Amapola, San Luis Potosí.

Referred material: UJMC 615, 62 specimens.

Measurements: Diameter: 2.5 mm.

Family Gastrodontidae Tryon, 1866

Genus Zonitoides Lehmann, 1862

Zonitoides arboreus (Say, 1817)

Ecology: Zonitoides arboreus occurs in woodlands and is associated with trees as well as living under shaded areas such as bark, leaves and stones (Leonard, 1950; Metcalf and Smartt, 1997).

Current distribution: From Canada through the southern United States, Mexico and Central America. The distribution in Mexico includes Chihuahua, Nuevo León, San Luis Potosí, Puebla, and Veracruz (Metcalf and Smartt, 1997; Naranjo-García and Fahy, 2010).

Stratigraphic remarks: At the El Molino Mammoth site, the stratigraphic distribution of Z. arboreus includes both Late Pleistocene and Holocene strata. The first Pleistocene record for this species was made by Arroyo-Cabrales et al. (2008) near the municipality of Villa Acuna in Coahuila.

Referred material: UJMC 616-617, +100 specimens (Late Pleistocene: +100; Holocene: 14).

Measurements: Diameter: 5 mm.

Genus Glyphyalinia von Martens, 1892

Glyphyalinia indentata (Say, 1822)

Ecology: This species can be usually found in leaf litter in forests, open meadows, and anthropogenic impacted habitats (Nekola, 2010).

Current distribution: Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Mexico and Guatemala. In Mexico, it has been reported from Baja California, Durango, Jalisco, Michoacán, Mexico City, Morelos and Puebla (Thompson, 2011).

Stratigraphic remarks: The stratigraphic distribution of G. indentata at the El Molino Mammoth site includes Late Pleistocene and Holocene A strata. The first Pleistocene record for this species in Coahuila was made by Arroyo-Cabrales et al. (2008) near the municipality of Villa Acuna.

Referred material: UJMC 618-619, 53 specimens (Late Pleistocene: 40; Holocene: 13).

Measurements: Diameter: 3.5 mm.

Family Euconulidae Baker, 1928

Genus Habroconus Cross & P. Fischer, 1872

Habroconus sp.

Ecology: Members of the genus Habroconus can be found in wooded and forested habitats, under rocks, leaf litter, shrubs and trees (Baker, 1930; Veitenheimer-Mendes and Aguiar-Nunes, 2001; Veitenheimer-Mendes and Postal, 2003).

Current distribution: Habroconus specimens in Mexico can be found in the states of Jalisco, Quintana Roo, Mexico, Michoacán, Nuevo Leon, Puebla, San Luis Potosí, Sonora, Tamaulipas, Veracruz and Yucatan (Pilsbry, 1919b; Baker, 1930; Thompson, 1967b; Correa-Sandoval, 1997; Araiza y Naranjo-Garcia, 2013; Naranjo-García and Fahy, 2010; Van Devender et al., 2012)

Stratigraphic remarks: The stratigraphic distribution of Habroconus sp. at the El Molino Mammoth site is limited to Late Pleistocene strata. This is the first fossil record of this species in Mexico.

Referred material: UJMC 620, 35 specimens.

Measurements: Diameter: 2.8 mm.

Family Pristilomatidae Cockerell, 1891

Genus Hawaiia Gude, 1911

Hawaiia minuscula (A. Binney, 1841)

(Figure 3h)

Ecology: Hawaiia minuscula is an inhabitant of humid environments, living on leaf mold, beneath the bark of trees and among mosses. It is capable of withstanding long periods of drought and high temperatures (Leonard, 1950).

Current distribution: Canada and United States. In Mexico, the species has been reported from Baja California, Sonora, Tamaulipas, San Luis Potosí, Veracruz, Puebla, Nayarit and Yucatán (Bequaert and Miller, 1973; Metcalf and Smartt, 1997).

Stratigraphic remarks: At the El Molino Mammoth site, the stratigraphic distribution includes the Holocene A, B2, C and D strata. Arroyo-Cabrales et al. (2008) reported H. minuscula from the Late Pleistocene locality of Rancho La Amapola near the city of San Luis Potosí.

Referred material: UJMC 621, +100 specimens.

Measurements: Diameter: 2 mm.

Family Agriolimacidae Wagner, 1935

Genus Deroceras Rafinesque, 1820

Deroceras laeve (O.F. Müller, 1774)

Ecology: Deroceras laeve has a circumpolar distribution and is considered a hygrophilous species. It can be found at low elevations among cultivated, urban and marshy areas. In mountains, it occurs along springs, streams and other bodies of water (Bequaert and Miller, 1973; Metcalf and Smartt, 1997; Rowson et al., 2014).

Current distribution: Originally, this species was found native to North America but can be found today on other continents as well. In Mexico, it has been recorded in Mexico City, Puebla and Veracruz (Bequaert and Miller, 1973; Metcalf and Smartt, 1997).

Stratigraphic remarks: The stratigraphic distribution of D. laeve at the El Molino Mammoth site includes the Late Pleistocene and Holocene A and C strata. The first Late Pleistocene record for D. laeve was reported from Rancho La Amapola near San Luis Potosí by Arroyo-Cabrales et al. (2008).

Referred material: UJMC 622-623, 17 specimens (Late Pleistocene: 11; Holocene: 6).

Measurements: Height: 4 mm; width: 2 mm.

4. Discussion

4.1. NEW MOLLUSCAN RECORDS

From the 14 mollusk taxa reported for the Late Pleistocene of the El Molino Mammoth site, all but three species were found distributed around Mexico and the United States Quaternary deposits. For the first time, we report the species Gastrocopta tappaniana, Pupilla hebes and Habroconus sp. for the Pleistocene of Mexico, of which the first two were previously known from Pleistocene deposits within the United States. Today, these species are extinct in the area, with G. tappaniana being mostly distributed outside of Mexico, usually from western to north eastern United States. In the case of P. hebes, recent distribution includes only the northern Mexican states of Chihuahua and Baja California, whereas specimens of the genus Habroconus can be found from the northern state of Nuevo Leon to the southern state of Yucatan. For the state of Coahuila, new Pleistocene records include G. tappaniana, G. obrussa, C. exiguum, G. parvus, P. hebes, D. laeve and Habroconus sp. The remaining species (E. compressa, F. californica, Succinea sp., C. lubrica, V. gracilicosta, Z. arboreus and G. indentata) have previously been reported from other Pleistocene sites around the state.

Of the 10 Holocene mollusk taxa reported from the El Molino Mammoth site, three species have been previously recorded from Holocene fossil localities in Mexico. These include G. obrussa and P. acuta from Coahuila (Czaja et al., 2019) and Succinea sp. from Sonora (Copeland, 2011). The remaining seven species, E. casertana, G. humilis, G. cristata, G. indentata Z. arboreus, H. minuscula, and D. laeve, are new fossil records for the Holocene of Mexico.

4.2. PALEOECOLOGICAL INTERPRETATIONS

Most of the El Molino Mammoth site mollusk taxa were also present during the early Quaternary in various sites of North America, making possible detailed paleoenvironmental interpretations through the available data associated with their environmental preferences and requirements (Carobene et al., 2018). Generally, species composition and abundance of certain taxa in each assemblage depend on climatic conditions and local ecological factors, especially vegetation cover (Sümegi and Krolopp, 2002; Carobene et al., 2018). The large amount of terrestrial mollusks from the Late Pleistocene strata of the El Molino Mammoth site is noteworthy (Table 2). Miller (1966) associated the same species (C. lubrica, Z. arboreus and G. indentata) with those from the Great Plains to be woodland associated and commonly found in forested areas among shallow bodies of water.

Table 2 The habitat requirements of the El Molino Mammoth Site Late Pleistocene and Holocene malacofauna (modified from Miller, 1966).

| Species | Habitat requirements |

|

C. exiguum

G. tappaniana D. laeve |

Hygrophilic: moist situations in shaded areas not far from water. |

| E. compressa | Perennial water: stream or lake with slow to moderate current and shallow spots not affected by seasonal drying. |

| G. parvus | Shallow quiet water: small body of water with no current or areas of rooted vegetation with little current, both not subjected to significant seasonal drying. |

|

Habroconus sp.

C. lubrica Z. arboreus G. indentata |

Woodland: moist areas under leaf litter, down timber, among tall marsh grass. |

| G. obrussa | Marginal situations: Wet mud, sticks, stones or any other debris along water's edge, also in shallow ponds and protected spots. |

|

V. gracilicosta

P. hebes G. cristata H. minuscula |

Sheltered situations: these species are not restricted to a woodland habitat and can tolerate drier conditions. |

|

F. californica

E. casertana P. acuta G. humilis |

Shallow quiet water: small body of water that may become dry during part of the year. |

| Succinea sp. | From relatively dry to humid conditions, preferring the later. |

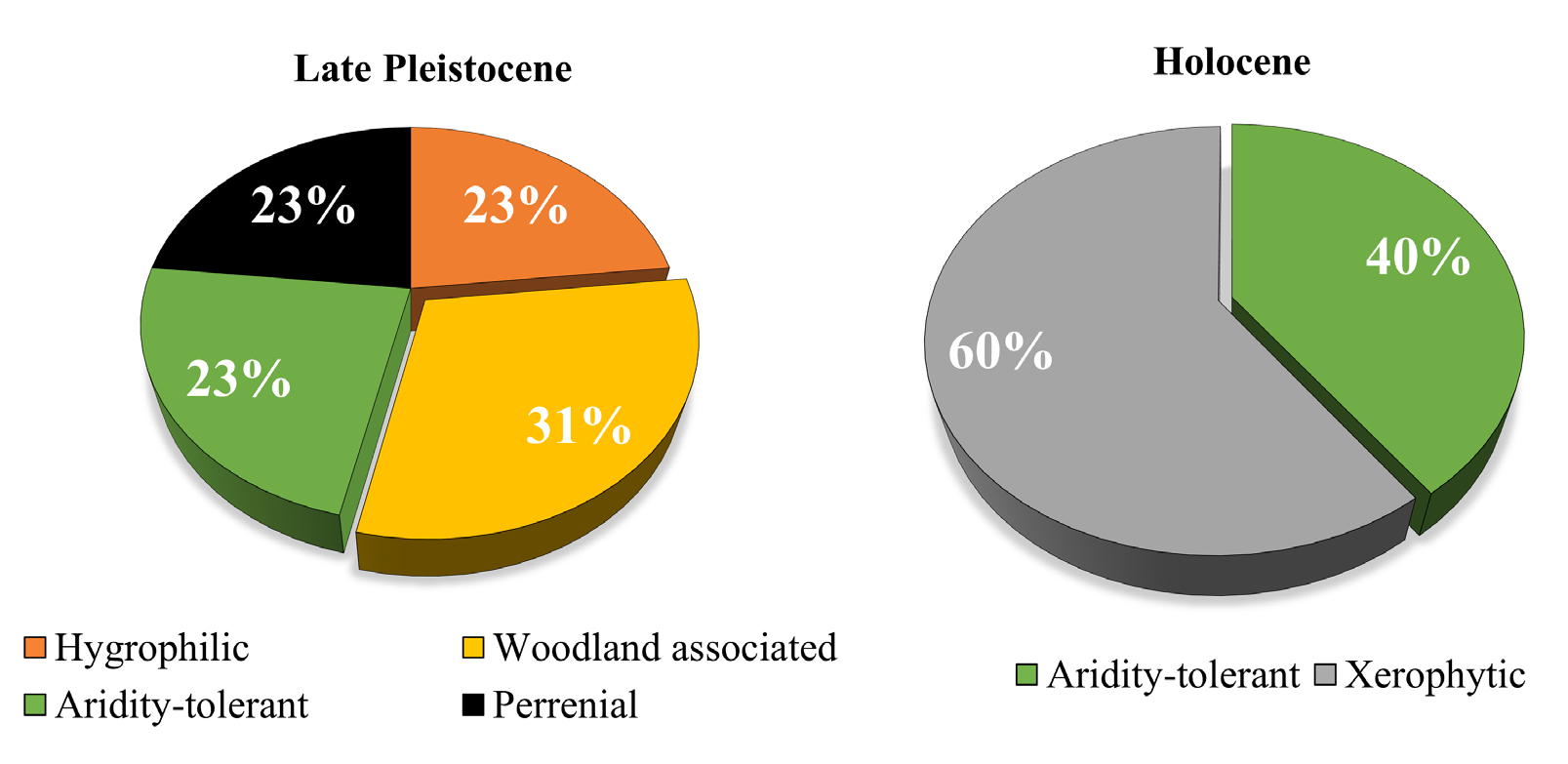

Additionally, the finding of numerous fragmental remains of fossil wood among the Late Pleistocene sediments confirm the presence of arboreous vegetation at the site. In addition, the area must have also supported grassland patches due to the numerous shells found of V. gracilicosta, a species commonly recorded from humid permanent bodies of water with grassland vegetation (McMullen and Zakrzewski, 1972). These habitat requirements well confirm the previous environmental interpretation given by Miller et al. (2008) for the site based on the vertebrate fauna. The fossil remains of horses, camels and other mammals found infer woodland and grassland habitats, thus supporting a community of species representing localized woodland interrupted by grassland habitats near a permanent body of water at the site. In the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene, the climatic conditions of the deserts in northern Mexico were much cooler than at the present (Metcalf et al., 2000). Most of the Late Pleistocene malacofauna of the El Molino Mammoth site did not survive the rapid environmental changes during the Pleistocene-Holocene transition. Notable in the El Molino Mammoth site profile is the sudden appearance of numerous species typically associated with grasslands such as, G. cristata and H. minuscula, and the simultaneous disappearance of wetland species (Figure 5). Both presumably reflect the striking change of climate conditions during and after the transition.

Figure 5 Generalized sediment sequence and malacofauna distribution from the abandoned well at the El Molino Mammoth site.

The early mid-Holocene was probably warmer and wetter than today, and true desert conditions did not set in until about 4000 yr B.P. (Metcalf et al., 2000). It is likely that the B horizon with its gypsum and calcium carbonate crystals represent these desert condition with dry climates and periods of evaporation and drought, and would likely explain the rapid colonization of the xerophytic elements in the profile that overall represent 60% of the malacofauna during this period (Figure 6). During the final phase of the body of water, there was an increase in the aquatic species P. acuta and G. humilis, accompanied by the aridity tolerant freshwater bivalve E. casertana. Agenbroad and Mead (1994) point to the abundance of Physella as indicative of warm waters. On the other hand, G. humilis is an excellent colonizer of new habitats and known for invading ponds devoid of vegetation and other species of gastropods (Jokinen, 2005). The ten species of the malacofauna that survived the transition into the Holocene are known for their tolerance of high temperatures (Miller, 1966). During this time, the site consisted of an ephemeral pond with predominant vegetation consisting mainly of short grasses and shrubs.

5. Conclusion

Our findings expand the mollusk data record known for Mexico with the entry of the three new Late Pleistocene gastropods, Gastrocopta tappaniana, Pupilla hebes and Habroconus sp. as well as seven new Holocene mollusk fossils, E. casertana, G. humilis, G. cristata, G. indentata, Z. arboreus, H. minuscula, and D. laeve, from the El Molino Mammoth site of Northern Mexico. The Late Pleistocene and Holocene molluscan fauna from the site provide a broader view of the paleoenvironmental changes that occurred in northern Mexico during this time period. The recorded species confirm the presence of a humid forested and grassland habitat capable of supporting the hygrophilic and hydrophilic malacofauna along with the fossil remains of horses, camels and other mammals. Many mollusk species were not able to survive the strong shift to the more xeric conditions after and during the Pleistocene-Holocene transition. The surviving freshwater mollusks relied on the ephemeral body of water until the long periods of drought resulted in the total evaporation of water from the El Molino Mammoth site.

Contributions of authors

The authors of this research are: Perla Guadalupe Butrón Xancopinca (PGBX), Alexander Czaja(AC), Martha Carolina Aguillón (MCA), Rosario Gómez Núñez (RGN), Ignacio Vallejo González (IVG) and José Luis Estrada Rodríguez (JLER). In addition, its specific contribution is: 1. Conceptualization: PGBX and AC; 2.Data acquisition: PGBX and AC; 3.Methodologic/technical development: PGBX and AC; 4.Writing of the original manuscript: PGBX and AC; 5. Writing of the corrected and edited manuscript: PGBX, AC, RGN, MCA, IVG and JLER; 6. Graphic design: PGBX; 7. Fieldwork: PGBX, AC, RGN, MCA, IVG and JLER; 8. Interpretation: PGBX and AC; 9. Financing: Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durando, Campus Gómez Palacio, Mexico.

Financing

Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durando, Campus Gómez Palacio, Mexico.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest with other authors, institutions or other third parties about the content of this article.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)