1. Introduction

Carbonatites are igneous rocks composed of more than 50 % of carbonates and less than 20 wt% of SiO2 (Le Maitre, 2002). However, their classification is still under discussion and many authors consider that magmatic rocks should be classified as carbonatites when they contain more than 30 % of modal carbonates, not including the SiO2 content (Mitchell, 2005). Carbonatites can be plutonic, hypabyssal or volcanic depending on their emplacement. They are typically associated to rift structures that are developed inside continental cratons (Le Bas, 1986), although they can be also related to other geological settings such as oceanic islands (Mangas et al., 1996; Widom et al., 1999) or orogenic belts (Tilton et al., 1998; Chakhmouradian et al., 2008).

According to experimental petrology data and isotopic studies of stable and radiogenic isotopes, is considered that carbonatitic magmas are originated in the lithospheric mantle (Wallace et al., 1988; Bell and Simonetti, 2010). Carbonatitic melts are marked by their high content in volatile elements, especially CO2 but also F, and their enrichment in strategic elements such as Rare Earth Elements, Nb or Ta (Wyllie et al., 1996; Chakhmouradian, 2006; Chakhmouradian and Wall, 2012). This point has generated a great interest in the study of carbonatites despite their rarity since only 527 carbonatite localities have been reported in the world.

An important part of the research studies in carbonatites are focused on the study of extrusive localities, since volcanic products can provide very significant information about the genesis and the composition of carbonatitic magmas and the understanding of experimental petrology data.

Extrusive carbonatites are extremely rare rocks, only 47 localities have been reported in the world until present-day (Woolley and Church, 2005; Woolley and Kjarsgaard, 2008). The majority of extrusive carbonatites are located in Africa and especially in the Eastern Rift where the only occurrence of an active carbonatitic volcano is found, the Ol Doinyo Lengai in Tanzania (Dawson, 1962; Dawson et al., 1995; Keller and Zaitsev, 2012). In the western margin of the African continent a magnificent example of carbonatitic volcanism is also reported: the volcanic area of Catanda (Kwanza Sul, Angola). It is formed by a group of small monogenetic volcanic buildings of carbonatitic composition cropping out in a 50 km2 graben hosted in Archean granites and it is delimited by the intersection of three different fault systems. The Catanda carbonatitic volcanoes are largely eroded and covered by Quaternary colluvial and epiclastic sediments, which partly obscure the original morphology of the volcanic edifices. However, seven different eruptive centres were distinguished, associated to tuff ring and maar morphologies (Figure 1; Campeny et al., 2014).

Figure 1 Geological map of the Catanda graben and the area of the Chiva lagoon (modified after Campeny et al., 2014).

The emplacement of the Catanda volcanic carbonatites is associated to the extensional domain of the Lucapa belt, which is a rift corridor defined by the NE-SW trending fractures of the Quilengues-Andulo fault system (Jelsma et al., 2009). The first magmatic activity reported in the Lucapa corridor is from the Paleoproterozoic (Sykes et al., 1978) but magmatism was also significantly important in the Upper Cretaceous, associated to the break-up of Gondwana and the corresponding opening of the South Atlantic Ocean (Moulin et al., 2010). Most of the Angolan carbonatites and kimberlites are distributed along Lucapa (Alberti et al., 1999) and were emplaced during the Cretaceous magmatic event (Torró et al., 2012; Calvo et al., 2011a; Calvo et al., 2011b; Robles-Cruz et al., 2012). Silva and Pereira (1973) and Torquato and Amaral (1974) reported a Cretaceous age for the Catanda carbonatitic volcanism of 92 ± 7 Ma based on the K/Ar dating of phlogopite from a tinguaite dyke outcropping in the area. However, the well-preserved morphology of the volcanic edifices, the nature of the pyroclastic materials and the existence of present-day geothermal and seismic activity in the same area suggest a recent age for these eruptive processes (Campeny et al., 2014; Campeny, 2016).

During the study of satellite images of the Catanda volcanic area we localised a small circular lagoon in the Chiva area, located outside of the Catanda graben and slightly far away from the main carbonatite outcrops. Field work carried out in the surroundings of this lagoon allowed us to distinguish carbonatitic dykes, thus indicating the possible relation of this area with the occurrence of the carbonatitic volcanism in Catanda (Campeny et al., 2014; Campeny et al., 2015). The aim of this work is to provide new information about the nature of the materials of the Chiva lagoon and to discern whether their formation is related to the carbonatitic volcanism of the Catanda region or whether it should be considered as a genetically independent event.

2. Methods

The petrographic study of carbonatitic rocks from the Chiva area was based on the identification of main rock-forming minerals and the description of textural features. It has been carried out by the use of optical microscopy using transmitted and reflected light. Scanning Electron Microscopy E-SEM was also used for more detailed analyses of mineralogical relationships and textures, using a Quanta 200 FEI XTE 325/D8395BSE with a Genesis EDS microanalysis system from the Scientific and Technical Centres of the University of Barcelona (CCiTUB). The operating conditions of the SEM were 20 - 25 keV, 1 nA beam current and a working distance of 10 mm from the sample to the detector. Detail images of the textural patterns were obtained in back-scattered electron (BSE) mode.

Geochemical data of major and trace element compositions were obtained by performing X-ray fluorescence (XRF) (Norrish and Hutton, 1969) and ICP-emission spectrometry following a lithium metaborate/tetraborate fusion, respectively, at the ACTLABS Activation Laboratories Ltd. in Ancaster, Canada.

3. The Chiva carbonatites

The Chiva lagoon, which is considered to be the source of the N’Dula river, islocated 350 km SE of Luanda and 5 Km NE of the volcanic carbonatitic outcrops of Catanda (Figure 1). It forms a shallow depression of 900 metres in diameter, surrounded by a smooth relief that defines a typical ring shape (Figure 2a). In the vicinity of the lagoon, farming activity is developed and original outcrops are largely covered by alluvial and colluvial sediments.However, a few carbonatitic dykescan be distinguished on the SE edge of the lagoon, forming coherent 1.5-metre-thick bodies (Figure 2b), radially arranged from the lagoon centre to its border.Outcrops are brownish in colour when weathered and dark grey in fresh sample (Figure 2c).

Figure 2 a. General view of the Chiva lagoon area. b. Carbonatitic dyke outcropping on the SE shore of the Chiva lagoon. c. Detail of typical porphyritic texture of the Chiva carbonatitic dykes.

3.1. Petrography

Carbonatitic dykes from the Chiva lagoon have a porphyritic texture with 20 - 25 % of phenocrysts and xenocrysts in a carbonate-rich aphanitic groundmass (Figure 3a), which also contains a large number of vesicles.

Figure 3 Plane-polarized light photomicrographs of Chiva carbonatitic dykes. a. General view (using parallel Nicols) of the carbonate-rich groundmass mainly formed by calcite (cal) and magnetite (mag). b. Crossed Nicols picture of Apatite (ap), magnetite (mag) and calcite phenocrysts hosted in a carbonatite-rich groundmass. c. Subhedraltabular phenocrysts of calcite together with magnetite (mag). Picture taken using crossed Nicols. d. Pelletal lapilli core comprised of a partially fractured and altered olivine (ol) crystal. Picture taken using crossed Nicols.

3.1.1. Phenocrysts

The population of phenocrystsis made up of calcite, apatite and magnetite. Calcite represents around 60 % of modal phenocrysts of the Chiva dykes, such as reported in the Ipunda lavas from Catanda area (Table 1). Calcite crystals are subhedral, with a distinct tabular habit and attain up to 0.25 mm in length (Figure 3a). However, they have an internal polycrystalline texture, suggesting recrystallization and pseudomorphosis processes (Figure 3b). Apatite crystals are subhedral to euhedral, composed by prisms and hexagonal bipyramids; they are short prismatic in habit and may reach a diameter of up to 0.3 mm, representing 30 % modal of the total phenocryst population. They are slightly zoned, with rims enriched in britholite component; hence, the rims appear slightly brighter in SEM-BSE images than the cores of these crystals. Magnetite forms clearly zoned euhedral octahedral grains up to 0.4 mm in diameter representing around 10 % modal (Figures 3a, 3b and 3c).

3.1.2. Xenocrysts

Rounded and corroded olivine grains, up to 0.6 mm, partly or completely replaced by serpentine minerals are common and may be interpreted as xenocrysts (Table 1; Figure 3d). In fact, olivine from the Catanda carbonatites has generally been interpreted as xenocrysts by different authors (Peres et al., 1968; Campeny et al., 2015).

3.1.3. Groundmass

The main components of the groundmass are calcite (60 % modal), apatite (10 % modal) and magnetite (10 % modal), presenting textural patterns similar to those described in the phenocrysts (Table 1; Figure 4a). In addition, variable proportions of magnesium-rich smectites (≈ 20 % modal) are widespread in the groundmass, forming cryptocrystalline masses that fill interstitial spaces (Figure 4). Minor proportions of accessory minerals such as pyrochlore and perovskite are also noticeable. The grain size of these minerals is very small, less than 5 μm (Figures 4a and 4b), and they are scattered in the groundmass or can also appear as inclusions inside magnetite grains. Both minerals develop euhedral to subhedral crystals, and zoning is not evident. Pyrochloreis slightly enriched in Zr while Nb content in perovskite is below the detection limit of the EDS. More rarely, we have also found small subhedral grains of kimzeyite garnet, up to 2 μm in diameter.

Figure 4 Backscattered scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of Chiva carbonatitic dyke samples. a. General view of typical porphyritic texture with magnetite (mgt), calcite (cal) and apatite (ap) microphenocrysts. b. Apatite (ap) prismatic crystals along side small grains of perovskite (prv) and magnetite (mgt), present in a calcite-rich (cal) groundmass, with abundant small inclusions of barite (bar) and magnesium-rich smectite (Mg-sme) in interstitial spaces. c. Detail of the groundmass with pyrochlore (pcl), perovskite (prv) and microphenocrysts of apatite (ap), magnetite (mgt) and calcite (cal) and interstitial magnesium-rich smectite (Mg-sme). d. Subhedral grains of kimzeyite (kmz) hosted in magnesium-rich smectite (Mg-sme) and associated to a calcite groundmass (cal) and a subhedral prismatic grain of apatite (ap).

3.1.4. Vesicula infill

Vesicular porosity is irregular in size and distribution. However, millimetre- to centimetre-sized amygdalae are rather common, and they are normally completely infilled by a supergene sequence of clay minerals, euhedral quartz and late spariticcalcite. Barite is also found in this assemblage as tiny crystals, less than 2 µm in length, commonly included in the calcite groundmass.

4. Geochemistry

Major and trace element compositions of Chiva carbonatitic dykes are compiled in Table 2. It also includes compositional values from different worldwide carbonatite localities for comparison, such as the lavas from the Catanda area (Angola), Fort Portal (Uganda), Oldoinyo Lengai volcano (Tanzania) and the aillikites from Aillik Bay (Canada) (Tappe et al., 2006; Eby et al., 2009; Keller and Zaitsev, 2012; Campeny et al., 2015).

Table 2 Major element composition of Chiva carbonatitic dykes compared to the composition of Catanda graben lavas. Values from Campeny et al.(2015). AL (aillikite lavas), NL (natrocarbonatite lavas), CCL (calciocarbonatitelavas), CD (carbonatitic dykes).

The carbonatitic dykes of the Chiva area have CaO contents of 35.52 to 34.27 wt%. These values are similar to those reported in the aillikitic and calcio carbonatitic lavas from the Catanda area and the carbonatitic lavas from Fort Portal, but significantly higher in comparison to the aillikites from Aillik Bay and the Oldoinyo Lengai fresh natrocarbonatite lavas. Despite that, altered natrocarbonatic lavas from Catanda and the Oldoinyo Lengai area present higher values of CaO, varying from 45.91 to 46.81 wt% (Table 2). In the case of MgO, Chiva dykes show values from 9.13 to 9.80 wt%, similar to the aillikitic and calciocarbonatitic lavas from Catanda and Fort Portal (Table 2). FeOt contents range from 8.40 to 8.34 and are also similar from those which are presented by the aillikitic and calciocarbonatitic lavas from Catanda, butthey are significantly lower than those reported in the Fort Portal lavas and, especially, in comparison to aillikites from Aillik Bay, that present values from 12.2 to 16.0 wt% FeOt (Table 2).

SiO2 totals vary between 12.7 and 13.5 wt% in Chiva dykes (Table 2), with similar contents to those reported in the calciocarbonatite lavas from the Catanda area, as well as in the lavas from Fort Portal (Table 2). In the case of the aillikitic rocks from Catanda and Aillik Bay, SiO2 values are significantly higher than in Chiva, varying from 14.29 to 23.33 and from 18.2 to 26.8, respectively.

We also carried out a general comparison between SiO2contents and the proportion of different elements found in Chiva dykes, that also include data from different carbonatitic rocks worldwide (Figure 5). In these diagrams it is possible to distinguish that the main compositional features of Chiva dykes are especially similar to those reported in the calciocarbonatitic lavas of the Catanda area (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Compositional relation between SiO2 and different major elements of Chiva carbonatitic dykes. Values are compared to those reported for Catanda lavas and other carbonatitic rocks worldwide. Values obtained from: Tappe et al. (2006); Eby et al. (2009); Keller and Zaitsev (2012); Campeny et al. (2015).

Chiva dykes have a significant enrichment in REE, presenting LREE contents from 100 to 1000 times higher to those reported in C1 chondrites and 10 to 100 times enriched in the case of HREE (Figure 6a). General values are similar to those reported in other carbonatitic rocks (Table 2) but they are not significant enough to be evaluated as an economic resource. REE patterns of the studied carbonatitic dykes from Chiva show clear negative slopes with a significant enrichment in LREE relative to MREE and HREE. These are similar patterns to those presented by the Catanda graben lavas (Figure 6a).

Figure 6 a. REE plot of Chiva carbonatitic dykes normalized to chondrite C1. b. Multi-elemental trace element composition of Chiva dykes normalized to primitive mantle (PM). Normalization values used in both diagrams are from Sun and McDonough (1989). Chiva carbonatitic dyke patterns are compared to Catanda lavas in both diagrams. Values from Campeny et al. (2015).

Multi-element diagrams also show very similar patterns between Chiva dykes and Catanda graben lavas. The carbonatitic dykes are systematically enriched in all plotted elements (including LILE, HFSE and REE) to PM (Figure 6b).

5. Discussion

The dykes cropping out in the SE border of the Chiva lagoon indicate the development of carbonatitic magmatism events in this area. Furthermore, considering the proximity of Chiva to the Catanda graben, where volcanic carbonatitic activity is well known (Silva Pereira, 1973; Campeny et al., 2014; Campeny et al., 2015), both carbonatitic magmatic areas are probably related.

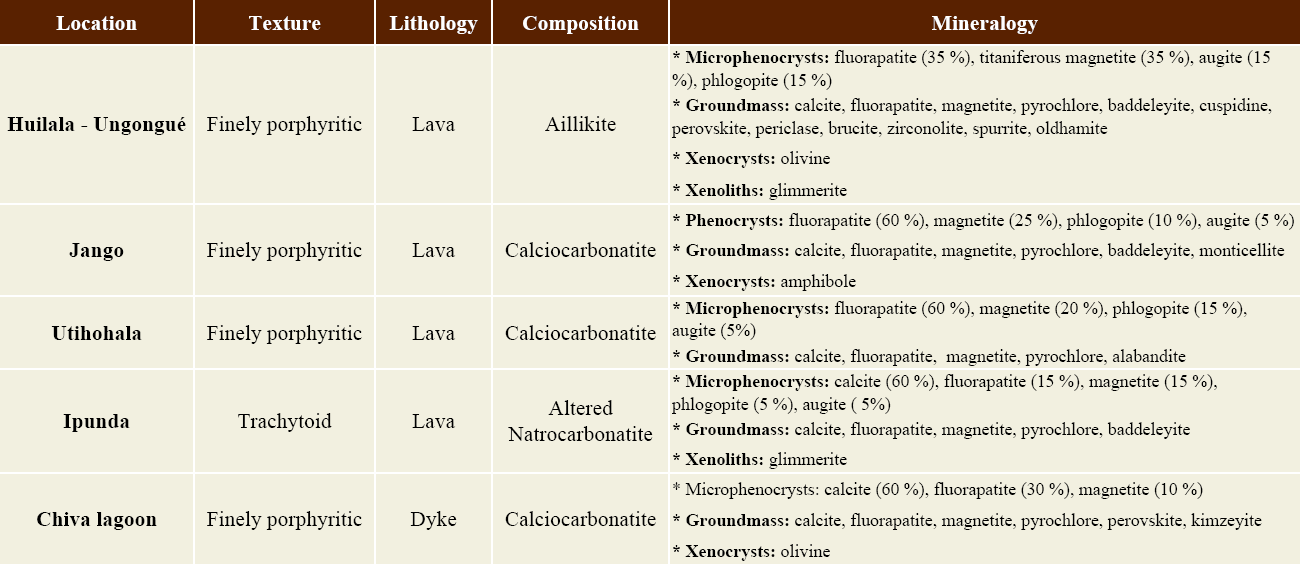

Mineralogical features of the Chiva carbonatitic dykes are very similar to those reported in the carbonatitic lavas from Catanda (Campeny et al., 2014; Campeny et al., 2015). Minerals such as calcite, apatite and magnetite are the main phenocryst phases in both localities, while the groundmass mineralogy is also equivalent. The latter is comprised of sparitic calcite and accessory minerals such as pyrochlore or perovskite; both reported in Chiva dykes and also in Catanda graben lavas (Table 1).

The comparison of major and trace element compositions between Chiva dykes and Catanda lavas also indicates a clear genetic relation. Multi-elemental and REE diagrams of Chiva carbonatitic dykes present equivalent patterns to those reported for Catanda lavas, suggesting that all these carbonatitic products were generated from the same parental melt. Major element composition is very heterogeneous in the case of Catanda lavas but the Chiva carbonatitic dykes are compositionally equivalent to the calciocarbonatitic lavas from Jango and Utihohala monogenetic cones. These volcanic edifices are also located in the most external part of the Catanda graben region (Campeny et al., 2014; Campeny et al., 2015). In addition, we can also conclude that carbonatitic dykes from Chiva present compositional and mineralogical features akin to other carbonatitic volcanic rocks worldwide such as Fort Portal (Uganda) (Eby et al., 2009).

Hence, considering the mineralogical and compositional features of the Chiva dykes, we conclude that these carbonatitic outcrops are related to the volcanic activity in Catanda despite the fact that Chiva is located outside of the Catanda graben. Therefore, we assume that carbonatitic volcanic activity in this area was also developed outside the limits of the Catanda graben and the discovery of new carbonatitic volcanic outcrops in this region should not be ruled out.

The radial distribution of the Chiva dykes, oriented from the lagoon centre to its border, and the morphology of the Chiva area, which is defined by a circular depressed ring, suggest that an eruptive centre was once located in the region. Hypabyssal intrusions related to volcanic edifices are common and broadly described in several volcanic areas of different composition worldwide (Gautneb and Guddmundsson, 1992; Geshi, 2005; Pasquarè and Tibaldi, 2007). Dykes are generated by magma intrusions during volcanic events and represent the magma path towards the surface (Corazzato et al., 2008).

Despite the fact that the morphology of the Chiva area is broadly eroded and covered by sediments and vegetation, the topographic position of the area, which is below the average altitude of surrounding terrains, suggests that the Chiva volcanic edifice has a maar morphology. Maars are volcanic constructions related to explosive activity and are commonly associated to recent carbonatitic volcanism such as in the Eifel region (Germany; Keller, 1981), San Venanzo (Italy; Stoppa, 1996), the East African Rift (Deans and Roberts, 1984; Woolley and Church, 2005) or even the volcanic edifices that stand out inside the Catanda graben (Campeny et al., 2014).

6. Conclusions

The main conclusions of our work can be summarized as follows.

Dykes of carbonatitic composition outcrop in the SE border of the Chiva lagoon area (Angola). They have been interpreted as hypabyssal intrusive sheets related to the occurrence of recent volcanic activity, producing a single eruptive centre with typical maar morphology.

Mineralogical and compositional features of the Chiva dykes are similar to those reported in the carbonatitic lavas of the Catanda graben area, suggesting that both volcanic events are genetically related. Moreover, the Chiva dykes also present compositional similarities to the volcanic silica-rich carbonatites of the Eastern African rift, such as Fort Portal (Uganda).

The genetic relation between Chiva and the Catanda graben suggests that the recent carbonatitic volcanism of the Lucapa domain has a broader extension than previously supposed. The discovery of new carbonatitic volcanic localities outside the main Catanda graben should not be discarded in this region of Angola.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)