Introduction

The recent ruling of the international court of justice-also known as the Court of the Hague-in terms of the maritime and territorial dispute between Colombia and Nicaragua, put into evidence the difficulties Caribbean states face in constructing a consistent border relations policy. The ruling produced a latent conflictual situation, both at the binational and regional level, that has mainly affected coastal populations and actors divided by conflicts over the sovereignty of their respective states and competition over access to important sources of natural, human, and sociocultural resources of great diversity1

This article will attempt to show the existence of a human and sociocultural unity in territories sharing borders in the Caribbean. Colombia (San Andrés Island), Nicaragua (Atlantic Region), Costa Rica (Limón and Cahuita), and Panama (Bocas del Toro and Colón), have common population dynamic origins and, thus, shared sociocultural, linguistic, and religious experiences that justify the creation of a border integration project. Despite the peripheral nature of these territories compared with their centers of power and, in some cases, the absence of integration policies to overcome conflicts, as well as rigid divisions imposed by the nation-states, social and family relationships persist on all sides of the state limits, showing the need for an effective strategy of border integration and development of a human, ethnic, and sociocultural character.

The methodology used for this study was based on a review of secondary sources, such as specialized books and magazines, from which matrices of characterization of the cross-border region were built using population, economic, and sociocultural elements2. in a complementary way, fieldwork was developed that used social mapping with members of the native community of the island of San Andrés, through participatory workshops where they drew their own life trajectories on the maps-family as well as economic and social ones-in the border territories and the maritime areas of the Caribbean.

The first part of the article will review the main theoretical discussions that have fed studies about borders in relation to the processes of construction of spaces and the social worldview of communities seated in border territories. The second part will suggest a general contextualization of the geohistorical configuration of the Western Caribbean, through the populations' trajectories and the processes of colonization of the border territories, placing special emphasis on the role played by the European powers-Spain and England-and in its projection from Jamaica toward the construction of an ethno-cultural zone. The third part of the article focuses on the linguistic, religious, and cultural characterization of the border zone territories that could eventually form a Cross-Border Integration Region in the Western Caribbean. For that the results of the social mapping workshops will be used as a way of showing cross-border connections that justify the development of various strategies of integration. Finally, some reflections and recommendations are made about the consolidation of a cross-border integration policy involving the Caribbean border territories.

Conceptualization about the border: softening of the border space

The notion of border has seen a significant advance, simultaneously with the transformation of modern political and social history over time. While this article does not seek to make an extensive reconstruction of the matter, it is worth mentioning the widely divergent concepts of the modern-day border, which has gone from the idea of being a place of separation with respect to barbarity and of virgin territory that needed to be appropriated (Taylor, 2007:232-236) to a notion of deterritorialization, porousness, of identifications that make contact, intermix, and restructure in an exercise of mutuality and reconfiguration on each side (Valhondo, 2010:136-137), moving to the idea of fixed territorial spaces, semantic constructions of space, and the discursive or textual construction of the border (Kurki, 2014:1057). The move from a simple to a complex concept of border policy consists of the departure from the classic paradigm of a physical and stable border toward the notion of a multispatial border in a state of constant change, given the more recent dynamics of cross-border human mobility, which tend to dilute the Westphalian linkage between territory and homogenous populations in the framework of the modern nation-state (Zapata, 2012:23).

This multispatial border concept is important for the purpose of this article, as concentrating on the idea of a porous and discursive border is key for understanding that, beyond the delimitations opposed by the nation-states, there are some borders constructed through linkages that go past the limits the states set. Thus, the border zones are articulated by border communities or representations of a life or lifestyles, where the centrality of the national discourses over those border spaces is lost and the paradigm of movement reappears (Kurki, 2014:1063).

This leads to an expansion of the border space, which is not limited to the zone of allowed (or disallowed) exchange of the nation-state, but to a territorial widening where exercises of belonging, common worldviews, and the suppression of limits imposed or represented in dynamics by the dominant power are generated. That a vast border zone could exist through a reconceptualization of the space is vital in assessing the importance of the border linkages and their possible scope for the local populations. in terms of the above, it is worth emphasizing the concept of deterritorialized community as an "entity that has escaped the comprehensive hegemony of the nation-state, upon being separated from a specific locality" (Garduño, 2003:75) and that constitutes itself, more than in the margin (avoiding the exercise of marginalization), through its own contact via historic dynamics of linkages of various types (commercial, ethnic, migratory, linguistic). This contact is where exercises of identity are generated through a community consciousness, where the existence of these limits is not established through physical materiality (maps, geographic lines), but through mental exercise or reflection (Maya, 2007). In this way, the border is an imagined space in constant reconstruction, through its development by local actors who produce its linkages, who experience it in their relationships and expand or reduce it, without necessarily having a correlation with the fixed geographic delimitation of the nation-state.

The constructions from the border, however, present themselves in a conflictual environment in the center/periphery relationship, now that it is in this duality where thought about these constructions has been articulated in the framework of the nation-state. From this perspective, it is understood that the border territory is a marginal space, constructed like a distant boundary not only spatially, but also dissociated from the economic and cultural development of the national territory (Giménez, 2007:22). From this, it follows that the border space must be safeguarded through policies of containment or forced inclusion, like the dynamics of the national arena, without necessarily recognizing that the border rebuilds its own dynamics outward, toward the other. Even so, these conflicts, together with the juxtapositions of the limits, the widening of the borders, the contact, and hybridization, show that the border lives and redefines itself, and turns into a story line created by those who live it. The border does not make reference to "a static, unmovable and non-negotiable reality based on a physical territorial line" (Zapata, 2012:41), but rather the result of a dynamic movement to a process of frontierization that allows the differentiation between dissimilar political communities and that, therefore, is based on a dynamic of inclusion-exclusion of citizen and foreigner.

All of the above has a Latin American correlation, produced through two factors. The first of these passes through the forms through which nation-building is built in the countries of the continent; the need to construct a homogenous identity, and for it have reach in the entire territory was realized in a dynamic of imposition from the top (elites) to the bottom (subordinates) (Grimson, 2005:131). The second is the current state of the borders, still in dispute by countries wary of losing their sovereignty, in contrast with processes such as the European one, where the erosion of borders makes the boundary lines and relations more fluid and less resisted by the centers, at the least in the purely European context, while generating exclusions outside that space.

But how is the border experienced by the populations of the greater Caribbean? Are these national projects imposed from above with misgivings about the loss of sovereignty, such as is the case in Latin America? This work aims to blur and reconstruct the borders experienced by the Afro-Caribbean population of Colombia, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, and Jamaica, intertwined not only in a long-standing relationship, but also in a dispute that goes beyond their spaces, just as other limits of a closer nature are imposed, such as the national interest.

The trajectories of the Caribbean populations' anglo-saxon projection of a hispanic space

The Southwestern Caribbean-which will be referred to, as well as the rest of the Caribbean, throughout this article-formed part of the process of the colonization of the Spanish Empire and later the British one; at many points it turned into an object of dispute from both, which in the end made it into a shared space of colonial domination. Similarly, it shared systems of common exploitation and migrations, be they of free people or slaves, with which the social configuration of the zone went about forming itself as a very particular society between the 16th and 18th centuries, with some common elements of identification where the tenuous borders of colonialism allowed it to transit in a shared space, until the imperial realm collapsed and those spaces were fragmented by the borders the new nation-state imposed.

Thus, although nation-states recognized as Hispanic are established in this zone, what is certain is that their Caribbean coasts and insular territories were connected with the dynamics of a Caribbean space whose Afro-British influence turned them into areas with common sociocultural characteristics, which differentiates them from the Hispanic and Catholic states, which defined these territories as their own. Then, an initial reconstruction of the trajectories of this cross-border population must be tied to the historic differentiation between the settled Afro-Caribbean populations, be they in the islands of San Andrés, Providencias, and Santa Catalina, or in the corridor of the Caribbean sea of Panama, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica, respective to their corresponding state. It can be said that it is a relation of recognition in contrast to the other, now that the historic routes and their products made it so that the struggle in identity construction confronts worldviews, which can be distinguished in the religious, linguistic, and other arenas. With that, the Afro-Caribbeans identified themselves as "liminal" populations (Sanmiguel, 2012:iii). The unity of these communities falls into overall patterns where it is difficult for them to have a good articulation with the majority identities constructed in Hispano-Catholic countries; the Afro-Caribbean communities are similar despite having different nationalities separated by formal borders.

Evidence of the foregoing, for example, is found in the importance the mission of the British Puritans had in what was once Old Providence, the settlements of descendants of Africans and Britons in coexisting for the development of activities for growing cotton, and the political leaders of British descent in the archipelago, without leaving to the side the ties brought about by the production of coconut with the united states and part of the anglophone Caribbean (Parsons, 1985:136-137; Avella, 2002:5, 13; Sandner, 2003:288); the close relationship between the Afro-Limón population, on the one hand, with the English via the migrations from Jamaica to the coastal zone of Costa Rica and later with the North Americans through the construction of the Panama railroad and the settlement of the United Fruit Company (Sanmiguel, 2012:34-36); the migrations and relations of the Afro-Panamanians with the Americans, through the projects undertaken for the construction of the canal (Avella, 2002:7), and the relation of the Nicaraguan Creoles with the British, produced for the Miskito protectorate established by them, where the Afro-Caribbean migrations from the islands had more room to maneuver, and were able to settle in with their culture together with the indigenous peoples who were established there (Sanmiguel, 2012:43-44; Avella, 2002:9-10; González, 1997:69).

The sociocultural matrix tied to these mentioned historic "contacts" will be reflected in various cultural aspects that will be reviewed later, but of which we can make some introductory remarks. For Avella (2002:4), the "English Caribbean and Protestantism is what has given symbolic unity to this diaspora," with which a differentiation was developed with the Spanish Creole identity project. Grouped by Protestantism, religious education in English, their skin color, and a kind of social service from various religious missions, which they did not receive either as slaves or as citizens, they went about consolidating a culture in the Western Caribbean (Sanmiguel, 2012:12). But the identity is consolidated also in the face of the threat of another, in this case the Creole-Hispanic projects of the consolidation of the nation-state. For this state, the homogenizing project of the Spanishs-peaking majority, with relatively similar characteristics, would build an idea of periphery, national pariahs, and a threat for those Afro-Caribbean spaces. Sandner (2003:288-289) says the construction of the periphery came about under the influence of catholic missions opposed to the Protestants and of the contrast of languages. Good examples of this are the evangelizing catholic project in San Andrés facing the already-established Baptist denomination; the Catholic missionary fathers expanded their border of faith toward the Moravian Creoles, leading the catholic missions to the utilization of exploitable resources, in the case of Panama and Costa Rica, and confronting the Protestant missions already in existence in the 19th century.

The construction of the nation-states of the white-mestizo variety at the beginning of the 19th century caused there to be marginalized communities inside their national spaces; Sanmiguel (2012:13) says that the best reflection of this was in the educational curricula, since it is in education as a modern project that a national project is built. Thus, the discourses of national identity were imposed on these ethnic identities, not corresponding to their worldviews, and being sanctioned through the imposition of the hegemonic project.

Considering all the above, it can be said that "a close connection of spiritual and cultural kinship persists among the English-speaking Protestant communities of the Western Caribbean" (Parsons, 1985:153), a kinship that was built, according to Mintz and Price (2012), in the cultural adaptations the African populations made to the circumstances in which they found themselves in America and then went about creating new forms of relationships in environments such as language, religion, worldviews, and daily life. These adapted inventions grew in the diaspora, being delineated throughout this study through the exploration of the specific cases of the zones in question.

Jamaica as the base for the construction of the ethno-cultural zone

The mention of Jamaica for the development of this characterization is fundamental. Although the heritages of the territories discussed in the Caribbean have various origins, the more characteristic traits of the Afro-Caribbean populations are connected to the island of Jamaica, as it is from there that the displacements began for the search-whether for freedom or work-transferring many of the characteristic traits of the enslaved inhabitants there. Pochet (2011:8) asserted this to be the case, and highlighted that:

Jamaica is one of the biggest islands in the Caribbean and was an important site for the distribution of slaves toward other points of the archipelago and of the continent. It also has been a cradle of English and Spanish settlements, as well as a key place in the dispersion of the Akan people in the Western Caribbean, from where Ashanti filaments were woven toward other islands of the archipelago and the American continent.

This shows what the germ of the Afro-Caribbean settlements in question is; also, the characteristics-to be reviewed further on-are the fruit of this diaspora. "The Raizals [in addition to the Creoles, the Afro-Limón population, and the AfroPanamanians] descended from slaves who came from Jamaica, and that is why the Creole spoken today in San Andrés [and the other territories studied] is very similar to the Jamaican patwa" (Clemente, 1989, cited in Ranocchiari, 2014:197).

Also, the influence that Protestantism had in its different variations is evident; its origins can be seen in Jamaica, which was linked to British influence and Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian, and Anglican missions (Davis, 2001:37). What is important about this point is that the identity constructed through resistance to the Catholics of the Hispanic world emerges from the role of the Protestant missions, inherited by those who migrated to the territories studied. also, the Baptist church assisted in the consolidation of the education of Jamaican slaves, through the Sunday schools (Davis, 2001:46-47), which ensured their linkages with the denomination and that Baptist churches are found in the territories in question, although they are not a majority in all the cases.

Sanmiguel (2012:19-30, 45) discusses the migrations from Jamaica to territories such as the archipelago of San Andrés, Providencia, and Santa Catalina, Bluefields and Limón, although in different circumstances, but showing the influence that the displacement of the afro population from that island, tied mainly to colonizing British companies, but not in a generalized way. one way to corroborate this is to look at the rooted cultural influence in terms of traditional practices involving the mystical and supernatural; "when the oldest [Creoles] are asked, they say those cults come from Jamaica and that it was the Jamaicans who developed them" (Zapata, no year:23). it is thus considered that Jamaica was the source that shaped the reaction to the circumstances that the migrants faced in the regions of the Caribbean studied, and it was there that these answers provide a support for an Afro-Caribbean identity. Elements such as language, religion, music, and oral tradition show this in Colombia's Caribbean islands and along the Caribbean coast of Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Panama.

Creole: diasporic languaje

Language and oral traditions are another element that allow the understanding of the historic affiliations among the regions being discussed. It is important to say "that Creole is an oral language-that is, it does not have a written alphabet-with an Akan base and an English lexicalization" (Botero, 2007:279). The consolidation of Creole with an English base and its similarity is the track that allows the grouping of these populations, not only through the processes of their consolidation, but in the practical exercise of its use and how it can be seen as being represented in oral traditions. Before going into more depth on the issue, it should be noted that creolization is based "on linguistic situations where there is a need for communication between people without a language in common" (Koskinen, 2006:45), a phenomenon that is commonplace to almost all of the experiences described below. For example, for the case of the archipelago de San Andrés, Providencia, and Santa Catalina, the structure of the plantation economy, the dynamics of the slaves on the islands brought by the English and the Dutch, and the Baptist education provided in the 19th century were the factors that deepened the roots of Creole and standard English in that zone (Moya, 2012:15-17, 19).

In the case of Limón and Cahuita in Costa Rica, the various waves of slaves and Afro-Caribbean populations to the coastal region of that country settled there, arriving as a result of railroad building and banana plantations through Anglo-Saxon projects, achieving a certain level of autonomy and consolidating their customs, among them the Creole language, as a form of communication reproduced by the Jamaicans and by those who came from the Nicaraguan coast. For Herzfeld (2003:172), the Afro-Limón Creole gained a foothold in Costa Rica because those who arrived there had to take with them their immigrant language (Jamaican Creole), which evolved through contact with the language of those who arrived from Nicaragua, resulting in what is referred to in those regions as mekatelyu.

In Panama, Aceto (2001:14-15) establishes two moments for understanding the arrival of Creole to Colón as well as Bocas del Toro. The author says that this occurrence came from the colonial phenomenon in the Caribbean and the reproduction of slavery, and because of the later arrival of Afro-Caribbean immigrants, in the post-emancipation period, in search of work along the Panamanian coast. in the case of Colón, the construction of the canal and the banana economy attracted these immigrants trained in Afro-Caribbean Creole, while in Bocas del Toro there were already Creole-speaking communities that had come from the islands of San Andrés, Providencia, and Santa Catalina, which entered into contact with migrations that sought to also establish themselves in that region in search of work, despite its being less accessible.

The development of Nicaraguan Creole came about through the direct arrival of slaves, and the later demand for these from the English. Also, the arrival of the free population of African descent from other latitudes of the Caribbean brought about a mixture that was replicated until the departure of the English from the region and the settlement of these populations together with the Miskito Indians in Bluefields and Pearl Lagoon, where the Creole culture managed to consolidate itself along with the language, with influences from the British and the Americans (Koskinen, 2006:46-47).

All of the above is reflected in the oral tradition, exemplified through the Anancy (spider trickster) stories of the Akan diaspora. The Akan are referred to as the populations to the south of Ghana, Ivory Coast, and Togo that form a linguistic family, who arrived in the Caribbean as a result of the slave trade conducted by the English (Pochet, 2011:2). Thus, "the cultural legacy of Anancy is an important manifestation of the symbolic capital of slaves transferred to the insular and mainland Caribbean" (Pochet, 2011:23). These stories refer to a spider that weaves together the diaspora of the slaves and are a manifestation of the part of the Caribbean studied (Pochet, 2011; El Nuevo Diario, 2008). Thus, we see how the language and the oral tradition reconstruct a cultural zone with similar patterns and shared narratives in this part of the Caribbean. although an exhaustive explanation of linguistic character would exceed the purpose of this work3, Table 1 shows, with basic aspects of the Creole syntax based on the English language, the proximity of the languages that are spoken in the territories studied, to back up what was shown by Patiño (1992:253), who placed these Creoles in the Western Caribbean group.

Table 1 Examples of Creole Written for Jamaica (J), Colombia (SAPSC), Panama (BT-C), Nicaragua (BF-CI), and Costa Rica (L).

| Miorphological aspects | Examples of Creole by territory |

| Pronouns: Regularities around the use of possessives as subjects. Use of "Unu" as a second person plural, of African origin | J: Mi, Im, Shi, Wi, Dem, Unu, Yu SAPSC: Mi (yo), Ihn, Shii, Wi, Unu, Dem BF -CI: Mi (A, Ah), Yu, Im (Ih), Shi, Wi, Unu, Dem BT-C: Mi (A-Ai), Yu, Im, Si, Wi, Unu (Yaal), Dem L: Mi (A, Miy) Im, Shiy, Wiy, Dem, Unu, Yuw |

| Adjectives: Use of reduplication upon qualifying a substantive | J: F i real, im big-big BF -CI: Dem gaan huom hapi hapi L: Mi graanimada mariid to a blak-black-black man |

| Formation of the plural: Use of the singular form and inclusion of dem as a plural | J: So, dem bwai-dem kom an dem f ling tuu brik an tuu bakl SAPSC: Di bwai dem de com BF -CI: Ih breda dem kuda neva fain notn fa iit L: Go tek up dem ipa ashes yu av tro ol abowt |

| Verbal forms in simple present tense: The base structure of subject+verb is maintained in its present form | J: Di man dem SAPSC: Mii laik black siil BF -CI: Ih ron muo fassa dah ih fren dem BT-C: Si doz sii si sista evri en da wiik L: Yuw pliye wid di marbel them |

| Verb forms in the simple past tense: It is seen that in the past simple, the verb keeps its neutrality in the present, depending on the context. Other past tenses sometimes use verbal particles (di, did) | SAPSC: Dem iit plenti dis maanin BF -CI: Unu faaget di best part BT-C: Mi trai it, mi di trai it L: Aal fers taym, mi did av a hant op guasimo |

| Negative form: Double negatives are commonly used with forms such as notn, neva, no, nat y niida | J: Nobady nuh live ova deh BF -CI: No aks mi notn nou! BT-C: Si no neva sin L: dat taym miy neva nwo was di nada brada mia fayt wid |

Source: Author's calculation based on Aceto (2001), Koskinen (2006), Forbes (2005), Portilla (2005), Pollard (2003), Durrleman (2000), Patrick (2003), and Herzfeld (2002).

Protestantism: the various branches of a non-catholic evangelization

Protestantism, with its diverse variants in the Caribbean, is another of the elements of affiliation that exist among the populations concerned. This point is important not only because of that affiliation, but also for the counterweight that it implies with respect to the Hispanic religious banner: Catholicism. The contacts with the English and the isolation in various historic moments of the regions consolidated a Protestant project resisted by the national religious discourses, hegemonic in large parts of the territory, and that are articulated to the other cultural elements proposed here.

In the case of the archipelago of San Andrés, Providencia, and Santa Catalina, the consolidation of the Protestant project took place, at first, as a result of the influx of the Puritans who settled in Old Providence. But the ratification of this project began with the founding of the First Baptist Church in 1845 by Philip Beekman Livingston, ordained in the United States and who propelled this evangelizing influx both on the island of San Andrés and that of Providencia (Parsons, 1985:139-140). The continuing Catholicism missions that sought the Colombianization of the archipelago had two effects; on the one hand, the reinforcement of the Baptist denomination, as this reproduced English-speaking patterns and was recognized as part of an authentic faith and also made of Catholicism an element of convenience for obtaining jobs, or a discourse that intended to destroy the bases of the islanders and their culture (Parsons, 1985:140-141; Sandner, 2003:343-344).

In the case of Puerto Limón and Cahuita, the religious relations connected with Protestantism were generated with a twin arrival: that of the Afro-Caribbean immigrants and religious missions. Zapata and Meza (2008:2417-2418) say that the Baptist, Methodist, Anglican, and Adventist missions appeared between 1888 and 1902, with great success in the region. The reasons are tied to the matching of the language-English in particular-and the existence of Afro-Caribbeans who had become Protestants and with a certain cultural development (Nelson, 1983:74). Also, the ability of these missions to be a motor of transformation in the lives of the inhabitants of the Caribbean in educational terms and in cultural strengthening helped them achieve a high level of legitimacy. it can be said that "the Antillean and the Protestant church thus begin a long and tortuous journey in their desire to build, in new circumstances, a new identity" given that the "church promotes the English language as a tool for improvement and resistance, for familiarity, religious cohesion, race, spirituality, and identity" (Zapata and Meza, 2008:2416, 2418).

The Panamanian case is broadly connected to the control of the Canal Zone and the Panamanian Caribbean coast on the part of the United States. Nevertheless, the first steps of Protestantism in this country were due to the Methodists, who arrived through the English and Jamaican settlements, according to Ravensbergen (2008:42), and influenced the Creoles of the region of Bocas del Toro. The author also takes note of other evangelizing Protestant campaigns, such as the Episcopal Church, which realized a wide-ranging work with the Caribbean populations, or the Seventh-day Adventists, who managed to establish themselves in the canal and Creole regions through schools, missions, and various churches. The appearance of the Jehovah's Witnesses and the Baptists also cannot be left out; the latter came from Jamaica.

Finally, similar historic routes in terms of religion are found in Nicaragua. Although here the evangelizing project that prevailed did not follow the patterns of the other regions, there were similar processes worth highlighting; first, the Anglican project was able to settle into Mosquitia (the Mosquito Coast), where the English lived together with the inhabitants of that region. Despite the difficulties, the Anglican consciousness managed to establish itself in eclectic form in Bluefields around 1896, very close to the Afro-Caribbeans, and extended to the rest of the inhabitants of the region, reaching as far as Corn Island (Holland, 2003:18-19). The Moravian church was able to consolidate itself in the Caribbean region of Nicaragua after it stopped concentrating just on the Anglophone Caribbean residents, to focus on the entire population diversity of the zone. The expansion from Bluefields to the regions of Pearl Lagoon and Corn Island recognized the roots achieved by this mission, of which it can be said that "the solidity of the Moravian work in the east of Nicaragua manifested itself in its permanence and growth" (Holland, 2003:21). In its European or North American variant, Moravian Protestantism was so influential in Nicaragua that it was connected to the coastal resistance during the Sandinista revolution and to the negotiation that would result in the edification of the regions of the Atlantic, both in the north and south (Epperlein, 2001). Nevertheless, it was not immune from the influx of the Catholic Church, which at the beginnings of the 20th century had already begun a move toward the Caribbean, with the foundation of schools and catholic missions that did not have the success they sought (Sandner, 2003:288).

Despite the differences in the missions, we found that in the regions under review a strong affiliation toward the Anglo world, based in this case on Protestantism that picked up the use of English and that separated the populations from the Hispanicized Catholic worldview. Baptists, Moravians, Adventists, and other smaller missions have in common such work involving separation, and also involving a formation of identity in the regions of the Anglophone Caribbean. This identity also has a correlation in more daily activities, such as music, where the ties also were woven through the rhythms that originated in Jamaica and from some variations produced in this Caribbean space.

The musical tradition: calypso and mento as the caribbean story

One of the environments where a transnational Caribbean culture is found in the countries studied is anchored in music. although there have been variations and evolutions over time, the roots of the musical sounds and expressions in the Afro-Caribbean areas of Nicaragua, Colombia, Panama, and Costa Rica have their origins for the most part in Jamaica, with some linkages to the islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The influence of calypso and mento on the identity of the countries' populations is worth mentioning.

Pulido Ritter (2010:7, 10) refers to the idea of a diasporic transnationality and a black cosmopolitanism, which evokes itself through the music of the Panamanian calypso group lord cobra, but this could be extended to the generality of the four countries. In the music, a "diasporic transnational recreation that crosses national borders" is found. Tied to the previously mentioned elements, music is a reflection of the reconstructed relations in this region of the Caribbean. The influence of calypso and mento in popular Afro-Caribbean culture is undeniable, because they reflect in good measure both the use of its language, such as the telling of its historical course inside its places of articulation.

For example, for the case of the Afro-Limón population of Puerto Limón and Cahuita, it has been established that calypso is one of the most important genres among the older generations and it has been attributed with two objectives, teaching about the people's Afro-Caribbean history, and the contrast with the present. Also, it is found that what originally served as a means of communication for the slaves now functions as an identity factor for the Afro-Limón population through the calypsonians (Razo, 2010:86).

In the case of the Afro-Panamanians, Pulido Ritter (2010:7), after discussing the exclusion of Afro-Caribbean identities and the invisibilization of all their cultural forms caused by projects of modern-day Panama, says:

What is the place of calypso in the country that, above all, is a place of articulation of a cultural subject, where if it does not represent official musical discourse, of the nation, well, that discourse does not exist in an official form; it is established and crosses ethnic borders that the descendants of the immigrants of the Antilles are associated with.

The author gives answer to the questions starting with the development of a culture of calypso in Colón and Bocas del Toro, spaces where the calypsonians of the Caribbean had a point of encounter to hold competitions or bring forth the best of the genre through representatives such as Mighty Sparrow4. What presents itself, according to the author, is a transnationalization of the Afro-Caribbean identity, brought by the diaspora and fed by Anglo-inspired languages, which form a counterweight and end up consolidating themselves like a parallel discourse to the Panamanian-Hispanic culture (Pulido, 2010:10).

In the archipelago of San Andrés, Providencia, and Santa Catalina, the contact with its Caribbean neighbors meant that calypso, mento, and reggae (the latter an evolved form of mento) manifested themselves as the typical music of their inhabitants. Apart from the previously mentioned mighty sparrow, Harry Belafonte5 forms part of the repertoire replicated by the islanders; themes also allude to customs and representations of identity (Valencia, 1989:174-175). It is said that:

These musical expressions arrived at San Andrés and Providencia in the 1940s and 1950s. Mento, for example, was adopted with some modifications, both in the organologic arena (where it was necessary to adapt new and fragile instruments), such as in the musical themes, where their own stories replaced those about foreign actions. However, their musical content remained intact. For its part, since the 1950s, calypso has been performed with an undeniable musical fidelity, respecting the patterns imposed by the other islands in the Anglophone Caribbean. nevertheless, their lyrics narrate the past of a tranquil and marvelous past that no longer exists, leaving to one side the convulsed life of the last 30 years of their history; in this sense, their lyrics were stuck in the beginning of the 1950s, a time of expansion of these songs, when some bands made calypso music even with lyrics in Spanish (Maya, 2003).

Although, according to Valencia (1989:175), calypso also had a foothold on the Nicaraguan Atlantic coast, it is easier to track the mento as the music the Creoles reproduced in that region. This can be tracked through Maypole dance music. Lewin (2007:325) says that the Creoles barely took note of the second and fourth rhythm of that element, to transform it into the musical and corporeal manifestation of the maypole, which has its own festival both in Bilwi and in Bluefields, where calypso and soca (calypso soul) also are performed. Thus, it is evident that there also is a clear cultural connection through music in the greater Caribbean region studied, with a broad heritage from Jamaica, although in this case also from Trinidad and Tobago, connected to the previously mentioned characteristics.

Reproduction of the connections through life stories

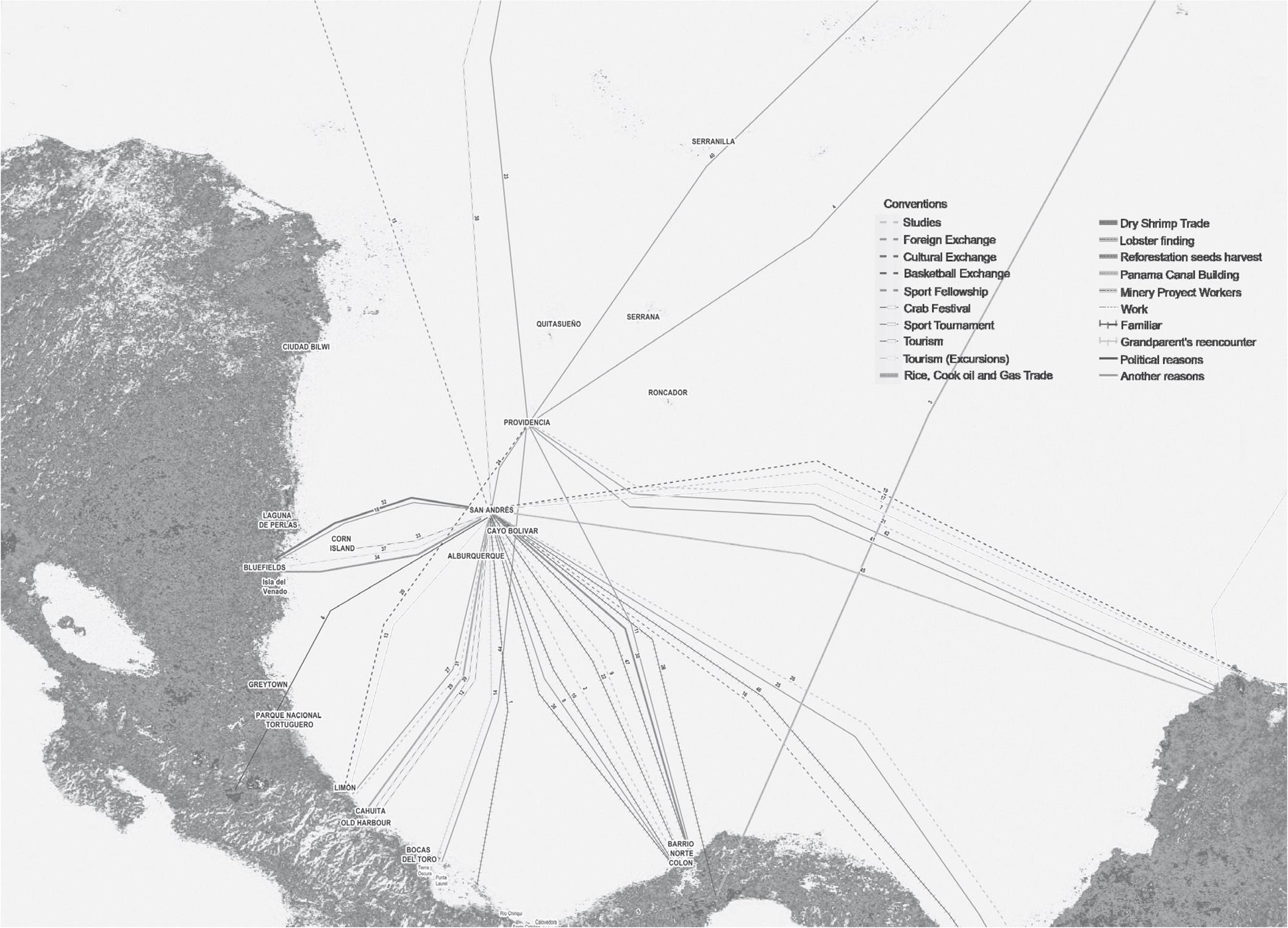

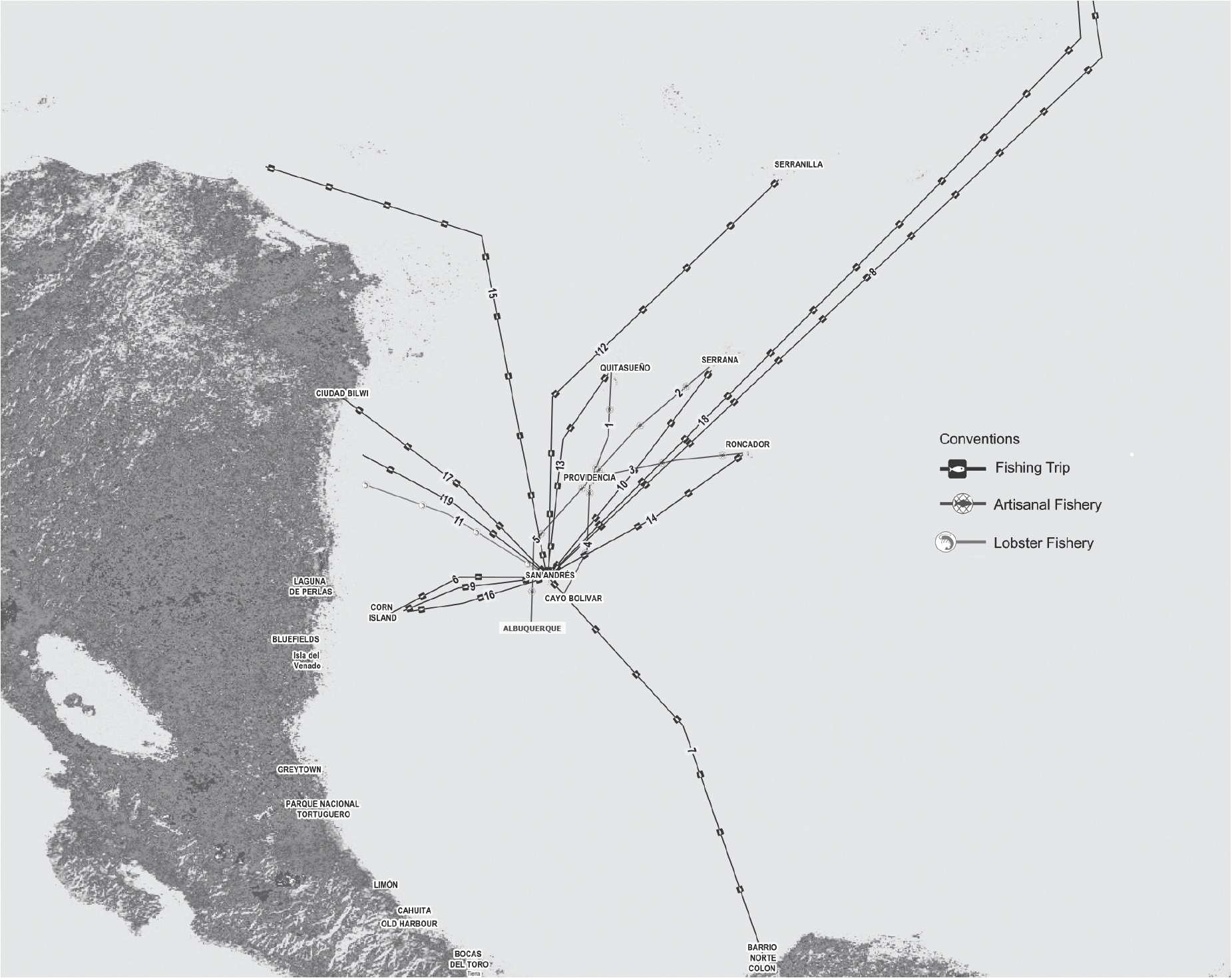

To this point it has been possible to discern how aspects of life such as religion, language, stories about identity, and music have been replicated culturally in the regions studied thanks to diasporic movements, cross-border relations, and consolidation of Afro-Caribbean identity, but can these linkages be seen today? (Table 2, 3, 4; Map 1).

Table 2 Path for reconstructing life trajectories in the Greater Caribbean.

| Rules for tracing routes on the maps | Essential questions |

| Participant:_____________________________ | Where are you from? |

| Mother: o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o | Where is your family from? Mom, dad, grandparents? |

| Father: I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I-I | What places have you lived? |

| Grandfather: ------------------------------------------ | Where are your children from? |

| Grandmother: OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO | What places do your family live or have they lived? |

Source: Authors' calculation based on the conventions for the reading of social mapping workshops realized in San Andrés, Providencia, and Santa Catalina.

Map 1 Reconstruction of family mobilities. Life trajectories in San Andrés, Providencia, and Santa Catalina (Caribbean Zone).

Table 3 Social cartography. Vital Paths of Families in the Greater Caribbean.

| ID | Origin | Destination | Year |

Mode of transportation |

Name | Occupation |

| 1 | Tobobe (Panama) | San Andrés (Colombia) | 1966 | River | Antonio Sjogreen | Unknown |

| 2 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Colón (Panama) | 1984 | River | Student | |

| 3 | England-Matinica | Panama | 1 | River | Antonios Sjogreen's Wife's Grandparents | Student |

| 4 | Switzerland | Providencia (Colombia) | 1 | River | Maria Ernestina Sjogreen Thyme's Great Grandfather | Unknown |

| 5 | Panama | Costa Rica | 1 | Land | Wife of Antonio Sjogreen | Student |

| 6 | Costa Rica | San Andrés (Colombia) | 1990 | Air | Unknown | |

| 7 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Barranquilla (Colombia) | 1991 | Air | Unknown | |

| 8 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Colón (Panama) | 1 | River | Mother of Maria Ernestina | Unknown |

| 9 | Colón (Panama) | San Andrés (Colombia) | 1941 | River | Sjogreen Thyme | Student |

| 10 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Colón (Panama) | 1 | River | Unknown | |

| 11 | Providencia (Colombia) | Colón (Panama) | 1 | River | Father of Ernestina Sjogreen Thyme | Unknown |

| 12 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Costa Rica | 2009 | Air | Elkin Lanos | TV Host |

| 13 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Costa Rica | 1 | Air | ||

| 14 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Panama | 2007 | Air | ||

| 15 | San Andrés (Colombia) | New York (U.S.) | 1996 | Air | ||

| 16 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Cali (Colombia) | 1997 | Air | ||

| 17 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Barranquilla (Colombia) | 1988 | River | ||

| 18 | Bluefields (Costa Rica) | San Andrés (Colombia) | 1 | River | Elkin Lanos' Grandparents | Unknown |

| 19 | Barranquilla (Colombia) | San Andrés (Colombia) | 1963 | River | Elkin Lano's Father | |

| 20 | Providencia (Colombia) | Puerto Limón (Costa Rica) | 2013 | Air | Willian Britton Steele | |

| 21 | Providencia (Colombia) | Cartagena (Colombia) | 1979 | Air | ||

| 22 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Colón (Panama) | 1 | River | Perla | |

| 23 | Great Cayman (Overseas Territory of Britain) | Providencia (Colombia) | 1 | River | Perla's Great Grandmother | |

| 24 | Providencia (Colombia) | San Andrés (Colombia) | 1 | River | ||

| 25 | Bogotá (Colombia) | San Andrés (Colombia) | 1982 | Air | Domingo Sánchez | Coralina's Worker |

| 26 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Bogotá (Colombia) | 1980 | Air | ||

| 27 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Costa Rica | 1979 | River | ||

| 28 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Panama | 1962 | River | ||

| 29 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Cahuita (Costa Rica) | 1985 | River | ||

| 30 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Bocas del Toro (Panama) | 1 | River | ||

| 31 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Costa Rica | 1977 | River | ||

| 32 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Bluefields (Colombia) | 1 | River | ||

| 33 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Corn Island | 1 | River | ||

| 34 | Bluefields (Costa Rica) | San Andrés (Colombia) | 1 | River | ||

| 35 | Cartagena (Colombia) | Dominican Republic | 2013 | River (Ship Glory) | Francisco Cruz Bailey | Reserve Officer |

| 36 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Colón (Panama) | 1 | River | Reserve | |

| 37 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Nicaragua | 1 | River | Officer | |

| 38 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Great Cayman | 1996 | River | Kayan Howard | University |

| 39 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Costa Rica | 1995 | River | Teacher | |

| 40 | Jamaica | Providencia (Colombia) | 1846 | River | Primer Howard | Baptist Reverend |

| 41 | Providencia (Colombia) | Cartagena (Colombia) | 1 | River | ||

| 42 | Cartagena (Colombia) | Providencia (Colombia) | 1 | River | ||

| 43 | England | Jamaica | 1846 | River | ||

| 44 | Providencia (Colombia) | Bocas del Toro (Panama) | 1 | River | Simón Jr Howrd's Children | Unknown |

| 45 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Colombia | 1 | River | John Saas' Grandparents | Musician |

| 46 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Cali (Colombia) | 2004 | Air | Loria Corpus | Cook and owner of native inn |

| 47 | San Andrés (Colombia) | Colón (Panama) | 1 | River | Loria Copus' Maternal Grandmother | Unknown |

Source: Compiled by the authors based upon Participants of Vital Paths Workshop.

Table 4 Social cartography. Vital paths of fishermen in the Greater Caribbean.

| ID | Origin | Destination | Year | Activity | Fisherman |

| 1 | Providencia | Quitasueño (Colombia) | -- | Artisanal fisheries | Diomiro Cabezas |

| 2 | (Colombia) | Serrana (Colombia) | -- | ||

| 3 | Roncador (Colombia) | -- | |||

| 4 | Cayo Bolívar | -- | |||

| 5 | Albuquerque | -- | |||

| 6 | San Andrés | Corn Island (Nicaragua) | 1985 | Fishing trip | |

| 7 | (Colombia) | Colón (Panamá | 1994 | ||

| 8 | Jamaica | 1999 | |||

| 9 | Corn Island Fishing Area (Nicaragua) | 1987 | Gabriel Vásquez | ||

| 10 | Roncador (Colombia) | 1990 | |||

| 11 | Ciudad Bilwi y Laguna de Perlas Fisshing Area (Nicaragua) | 1986 | Lobster fishing | ||

| 12 | Serranía (Colombia) | 1990 | Fishing trip | ||

| 13 | Quitasueño (Colombia) | 1990 | |||

| 14 | Roncador (Colombia) | 1990 | |||

| 15 | Honduras | San Andrés (Colombia) | 1980 | Pallardo Martínez | |

| 16 | San Andrés (Colombia) | San Andrés Fishing Area (Colombia) | -- | López | |

| 17 | Nicaragua | 1992 | |||

| 18 | Montigo Bay y Black River (Jamaica) | -- | |||

| 19 | Zone in dispute (Nicaragua-Colobia) | 2013 |

Source: Compiled by the authors based upon Participants of Vital Paths Workshop.

In this last section the results of the work with the native population (Raizal) in San Andrés, Providencia, and Santa Catalina will be shown, where the life trajectories of the inhabitants of the archipelago will be reflected through social mapping. This is essentially based in producing a representation of realities of a certain territory, through the socialization and discussion of the personal histories of each one of the participants. This is like the final result of the social mapping, specifically for these workshops6; they were maps of the area characterized with lines and tracings that go from one place to the next with specific descriptions: fishing routes, family trips, moves out of the country, and foreign study, among others. (Map 2, Table 5).

Map 2 Reconstruction of Fishing routes. Life trajectories of Fishermen in San Andrés and Providencia (Caribbean Zone).

Table 5 Participants in the life trajectories workshops*

| Name |

| Dionisio Cabezas |

| Elvis Lever |

| Gabriel Vásquez |

| Kayan Howard |

| Elkin Llano |

| Daniel Ariza Pacheco |

| Lucía Corpus |

| Juan Carlos |

| Francisco Cruz |

| Job Saas |

| Maritza García |

| Elizabeth Urrego |

| Domingo Sánchez |

| Antonio Sjoogreen and family |

| Loria Corpus |

| Carlos Calle |

*The Universidad Nacional de Colombia Sede Caribe thanks all those who shared the stories and trajectories of their family and work lives.

Source: Authors.

For the development of the workshops, understandings were set up to facilitate constructing the trajectories and their later study; in addition there were some guideline questions to channel the socialization of the trajectories.

In the maps resulting form that exercise-1 and 2-it is seen how the selected population-the islanders of San Andrés, Providencia, and Santa Catalina-go about weaving, through their stories, a familiarity with all the populations of the Caribbean studied here. Through recent and past trajectories, they go about connecting the territories that have a common history, common last names, and a history that connects the populace beyond the strong national spaces.

Something similar occurs with the circuits of the fishermen. In the described routes there are no explicit mentions of national restrictions; the Caribbean also becomes a space of navigation and accommodation, as can be seen in the circuits toward what is known as the Western Caribbean and Jamaica.

What all the above shows is that the dynamics of the population go beyond the determination of the national and that there is an almost instinctive form of appropriation in the Caribbean, through the stories intertwined in the migrations, language, and customs described here, which have a correlation in the traits that these life trajectories exhibit.

Conclusions

At present, institutionalized border integration policies do not exist for the neighboring populations of the countries studied in this article. This situation is explained in various ways: 1) the difficulty in implementing integration mechanisms in maritime contexts, where the border populations are isolated by the sea, 2) the peripheral condition of these border zones, which share the conditions of being neglected and marginalized by their central states, which, in turn, have given little importance to their maritime spaces, ignoring and invisibilizing the societal processes and the configuration of a sociocultural unit that has historically transcended the limits of the nation-state, and 3) the predominance of a sovereign view and of a dispute over the border zones, more than cooperation and integration.

The search for mechanisms and institutionalized forms of border integration in the area studied is of particular importance, given that, as has been shown, a wide gamut exists of shared elemental and historical relations that originated in a sociocultural matrix of African and Anglo-Saxon heritage, consolidated by a common language (Creole), an affiliation to the Protestant form of Christianity, and countless customs of a musical, gastronomic, and cultural character that are practiced in a shared manner and that have survived over time until today.

It is worth mentioning that the studied populations are moving along the road-some more quickly than others-of autonomy and the recognition of their rights such that they strengthen their ethnic and social identities, which inevitably bring with them the search for further engagement with the populations' border and transnational communities. The inhabitants of the islands of San Andrés, Providencia, and Santa Catalina, for example, continue to propose establishing a Raizal law that would allow a true empowerment of the ethnic group in the legal and political order of the archipelago. In Nicaragua, the Afro-Caribbean population has managed to consolidate a level of autonomy in which the Atlantic Autonomous Regions have fought for the recognition of the diversity and autonomy in Nicaraguan society, in keeping with the needs of the worldviews, realities, and goals of the populations living there, achieving important advances on issues such as the formulation of bills by the autonomous regional council and the Languages Law.

In Costa Rica, multiculturalism is recognized, although a specific ethnic recognition does not exist; now there is a homogenizing grouping between the indigenous peoples and Africa descendants (Brenes, no year:8-9). However, the struggles of the afro-Limón population for access to higher education, participation in national policy, and recognition of their identities (such as occurs in the Sawyers Languages Law, put forth by a female Afro-Limón legislator) show that the issue of recognition is gaining momentum in the country. Finally, in the Panamanian case, the actions today in the country point toward the recognition of the afro-Panamanian, although as specific measures to combat racism and discrimination (Brenes, no year:32) although without providing any type of special mention or autonomy to these populations, as does occur for the case of the indigenous populations.

The formation of a Cross-Border Integration Region would be the ideal scenario for common efforts to be made for identity recognition and the autonomy of the populations that inhabit the Caribbean border space studied for this work. This does not call for ignoring the state structures and systems each border population belongs to, nor does it ignore that despite having a common past, border areas also can be immersed in conflicts, be they over border lines or because of nation-state interests being projected into economic or political arenas. Thus, identifying similarities in their historic constitutions and in some of their circumstances in their national spaces would allow the formation of a Cross-Border integration region through a set of institutionalized policies, which must start, first and foremost, from the needs and visions of the inhabitants of the territory, of its particular relation with maritime space, and using a flexible model that facilitates human mobility and sociocultural rapprochement. This proposal must be incorporated employing government orders and local actors as protagonists in the process, but in a way that avoids to the greatest extent possible the bureaucratization of the mechanisms of integration, and the infiltration of national interests. This requires, among other things, knowing and harmonizing those mechanisms of the legal, political, and administrative orders of the territories-both national and border ones-that allow integration to advance. Once more, this can only result in the recognition of its actors, institutions, and policy agendas, as well as the arenas of integration, which would be the central axes for integration in this Caribbean Sea border area.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)