Introduction

Invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) is essential in the management of critically ill patients in the intensive care unit (ICU). As it is not a safe therapy for critically ill patients, increasing the days of ventilation increases the risk of infections, functional sequelae, weakness of the critically ill patient, diaphragmatic dysfunction, lung injury induced by mechanical ventilation, cognitive impairment, with an impact on the days of hospital stay, increased care costs, and morbidity and mortality1-3. The implementation of strategies to reduce the duration of IMV is of utmost importance for the prevention of these complications. However, the withdrawal of mechanical ventilatory assistance without prior evaluation can lead to extubation failure and the immediate need for reintubation with a direct increase in patient mortality. The spontaneous breathing test (SBT) is the most important evaluation for deciding when to withdraw IMV4. Its purpose is to test the ability to breathe without ventilatory support5 and to exclude those in whom the cause that led to support has not yet been resolved. SBT is necessary in all patients with IMV > 24 h, once the cause of intubation has been resolved3,6. Removing sedation as soon as possible and performing daily SBT will allow the timely identification of patients who no longer require ventilatory assistance and reduce the time of exposure to the potentially harmful effect of IMV7.

The objective of this article is to present the different methods of performing SBT, the evidence, and considerations in special populations (cardiac, obese, and pediatric patients).

Prolonged and premature withdrawal

Prior to SBT, it is necessary to determine if the patient is fit to withdraw from IMV (Table 1). Delaying or accelerating IMV withdrawal can have direct repercussions on the patient's condition and prognosis. On the one hand, prolonged use of IMV unnecessarily exposes clinical complications, in many cases derived from prolonged sedation, which generates greater morbidity due to the increased risk of pneumonia, the appearance of functional and cognitive sequelae, and increased mortality1,3,8.

Table 1 General patient selection criteria for SBT

| Sufficient resolution or improvement of the cause of intubation |

|---|

| Neurological |

| GCS ≥ 13 |

| RASS entre +1 y-2 |

| Without continuous sedation |

| Ability to initiate active inspiration |

| Hemodynamic |

| PAS 90-160 mmHg |

| FC < 130/min |

| Without vasopressor or low dose |

| Body temperature ≤ 38° |

| Negative fluid balance |

| Respiratory |

| SaO2 > 90% |

| PaO2 > 60 mmHg |

| FiO2 ≤ 0.4 |

| FR < 35/min |

| Tidal volume > 5 mL/kg |

| RSBI < 100/min |

| PIMáx ≥ 20 cmH2O |

| PaO2/FiO2 ≥ 150 mmHg |

| PEEP ≤ 8 cmH2O |

| Peak cough flow 60 L/min |

| Not copious secretions (< 3 aspirations in the last 8 h) |

| Acid-base balance |

GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale; FiO2: inspired fraction of oxygen; HR: heart rate; RR: respiratory rate; PEEP: positive end-expiratory pressure; Pao2/FiO2: arterial oxygen pressure/inspired fraction of oxygen; SBP: systolic blood pressure; PIMax: maximum inspiratory pressure; PaO2: partial pressure of oxygen; RSBI: rapid shallow breathing index; RASS: Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale; SaO2: arterial oxygen saturation.

Premature disconnection, when the patient does not yet have the capacity to maintain independent ventilation, has shown a high rate of reintubation3. This not only prolongs the use of IMV but also increases the infection rate, the days of stay in the ICU, the days of hospital stay, and, above all, increases the mortality rate6,8,9. According to a systematic review, patients who fail extubation are 7 times more likely to die and 31 times more likely to spend 14 days or more in the ICU10.

Ventilation por breathing

The SBT allows us to assess the patient's ability to breathe independently with the aim of removing IMV5. Among the different techniques, the most studied and compared are the T-piece test and the pressure support ventilation (PSV) test11.

T-piece test

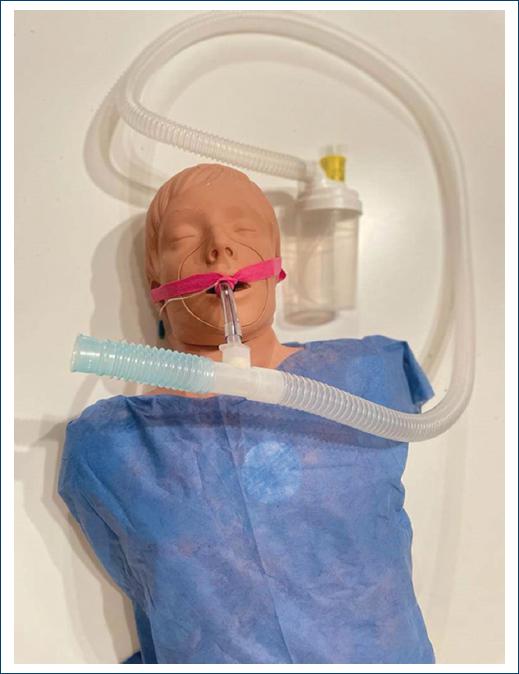

To perform it, the patient must be disconnected from the ventilator, and additional oxygen must be provided without positive pressure (Fig. 1)12.

Pressure support (PS) test

This technique is carried out with low levels of PS (which allows the resistance of the respiratory circuit to be compensated) and may or may not provide positive pressure at the end of expiration positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP). Unlike the T-piece test, this does not require disconnecting the patient from the ventilator, allowing different parameters to be continuously monitored. During SBT, you can know values such as expiratory volume, and calculate the minute volume and the rapid superficial respiration rate. Along with what was mentioned above, the implementation of this technique has other advantages, such as providing adequate humidification, establishing the corresponding alarms for patient safety, and the ease and speed of adjusting to previous ventilatory parameters in case of failure. SBT and by avoiding disconnection of the ventilator reduces the risk of aerosol spread4.

When comparing these techniques, different studies concluded that both allow reflecting post-extubation physiological conditions13. Without showing significant differences in the extubation success rate, reintubation rate, days of stay in the ICU, in-hospital mortality, ICU mortality, and the reasons for reintubation. Within the physiological constants, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and CO2 levels also did not have much difference. The only values that showed a significant increase were respiratory rate and SpO2 when performing PRE with PSV4,11.

Although both techniques prove to be effective (Table 2), SBT with PSV technique seems to be the most recommended when taking into account the aforementioned advantages. Therefore, although a consensus has not been reached regarding the parameters for its implementation, it can be determined that in general populations providing a PS ≤ 8 cmH2O, PEEP 0 cmH2O (Fig. 2) and with a duration of 30 min is sufficient to evaluate the patient's ability to breathe spontaneously4,6,7. This reduces the respiratory effort required without increasing the risk of failure and reintubation compared to the application of other techniques with different parameters13. This is because a considerable increase in ventilatory demand can contribute to SBT failure7. According to a study in the general population, reconnection to the ventilator after achieving a successful SBT or providing non-IMV (NIMV) after extubation does not show differences in the frequency of reintubation when compared4.

Table 2 Comparative table SBT with T-piece and PRE with PSV

| Type of test | T-piece | Pressure support ventilation |

|---|---|---|

| Method | Fan disconnection. | Decrease in ventilatory parameters (PS and/or PEEP) |

| Direct oxygen administration | ||

| Advantages | Reflects post-extubation physiological conditions | Reflects post-extubation physiological conditions |

| Allows monitoring | ||

| Does not require disconnection of the respiratory circuit. Provides adequate humidification | ||

| Allows you to set alarms. | ||

| Reduces the risk of aerosol spread | ||

| Disadvantages | Lack of monitoring FiO2 inaccurate | Increased respiratory rate |

FiO2: inspired fraction of oxygen; PEEP: positive end-expiratory pressure; PS: pressure support; PSV: pressure support ventilation. Adapted from Bellani5.

Spontaneous breathing trial in special populations

In the general population, reintubation after a planned extubation is between 10% and 15% and can exceed 20% in the high-risk population. This figure guides us to recognize patients whose characteristics increase their risk of failure to carry out a more specific evaluation and intervention, bringing them closer to success14,15. Patients will be considered high risk when their age is over 65 years or they have a disease that chronically affects heart or lung function12,15.

Cardiopathic patients

Failure to extubate of cardiogenic origin may be secondary to the presence of pathologies that compromise the response of the cardiovascular system to the transition between positive pressure ventilation and spontaneous ventilation. Normally, this occurs during the SBT16. The most relevant pathologies within this population include the presence of left ventricular dysfunction, a history of pulmonary edema of cardiogenic origin, reported ischemic heart disease, and permanent atrial fibrillation12,15. On the other hand, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, associated with positive fluid balance, also have a high risk of failing extubation due to cardiogenic origin16.

According to the literature, for these patients, the most appropriate SBT is the T-piece with a duration of 2 h, since this offers the workload to the cardiorespiratory system equivalent to that required post-extubation17. This test also allows heart failure to be manifested in patients with deterioration in cardiac function or suspicion thereof, with the aim of identifying the risk of failure and treating it before performing an extubation that could fail. Because this test is sensitive in evaluating the ability to breathe spontaneously and independently, failure during this evaluation implies the need to optimize cardiac conditions before and after extubation16.

Immediately after extubation, in these patients, a benefit has been reported by providing ventilatory support, alternating the use of high-flow nasal cannulas between NIV sessions, to reduce the risk of reintubation as well as respiratory work15.

Obese patients

Obesity is a condition in which fatty tissue deposits occur in the neck, thorax, and abdomen, directly impacting the functionality of the respiratory structures18. These accumulations of fat together with a high body mass index cause cephalic displacement of the diaphragm increase pharyngeal collapsibility and resistance of the upper airway, facilitate the collapse of the small airways, increase the work of breathing and predispose to atelectasis19,20. Consequently, a restrictive pattern is generated, with a reduction in the compliance of the respiratory system, the functional residual capacity, the inspiratory and expiratory reserve volume, the total lung capacity, the vital capacity, and the mechanical function of the upper airway19,20.

Due to changes in respiratory mechanics and physiology, obesity is associated with an increase in the basal metabolic rate, impairment of gas exchange, hypoxemia, hypercapnia linked to hypoventilation, and decreased safe apnea time19,20. In these patients, airway management and maintaining alveolar protection parameters must be optimal since in periods of apnea the oxygen concentration decreases rapidly, due to the increase in the percentage of oxygen consumption used in respiratory work18.

For these patients, there are two techniques that precisely simulate the inspiratory effort and post-extubation respiratory work, this is through the T-piece tests and the one that provides PS 0 cmH2O + PEEP 0 cmH2O (Fig. 3), in both. cases lasting 30 min. This is due to the fact that if PRE is performed with positive pressure in the respiratory circuit, the post-extubation respiratory work is underestimated4,19,20.

Once IMV is withdrawn, a transition to NIMV may be considered appropriate, which allows positive pressure to be applied to the small airways to keep them open and also counteracts soft-tissue collapse at the level of the upper airway19.

Spontaneous breathing test in pediatric patients

The need to recognize the preparation of pediatric patients to be able to be extubated successfully has extensive support established in the literature related to the topic. However, there is no clear consensus about the parameters necessary for this evaluation21. In most cases, withdrawal is decided according to the judgment of the treating physician or, if an evaluation is performed, a significant proportion of patients show they are ready to be extubated, suggesting that this process was not initiated in a timely manner22. Although the SBT allows us to evaluate the ability and preparation to breathe independently, in this population in particular, failure in the test does not always indicate the same for extubation23.

There are two mainly documented techniques to perform the SBT, firstly providing an established PS regardless of the size of the endotracheal tube (ETT), this figure is usually 10 cmH2O, which has been shown to underestimate the post-extubation respiratory work23. Secondly, PS would be titrated according to the size of the ETT, a technique that overestimates preparation for extubation23-25. By discarding the previous methods due to their lack of capacity to reproduce post-extubation conditions, according to the reviewed literature, it is then recommended to perform SBT with PS of 8 cmH2O, with PEEP 5 cmH2O for 2 h22-26.

While it is recognized that more studies are required to determine the parameters necessary for adequate evaluation, it is clear that using a protocol compared to extubation based on clinical judgment reduces the failure rate (Table 3) 24,26. It is also noteworthy to mention that in the pediatric population after congenital heart surgery, a decrease in days in intensive care was also found, without reducing the duration of IMV or the days of hospitalization26.

Table 3 Summary of suitable parameters

| Population | General | Cardiopathy | Obese | Pediatric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | VMI > 24 h | VMI > 24 h | VMI > 24 h | VMI > 24 h |

| Over 18 years | Presence of pathologies that compromise the response of the cardiovascular system | IMC > 35 kg/m² | Under 18 years old | |

| Method | PSV | T-piece | T-piece or PSV | PSV |

| Parameters | PS: ≤ 8 cmH2O | Duration: 2 h | T-piece | PS: 8 cmH2O |

| PEEP: 0 cmH2O | Duration: 30 min | PEEP: 5 cmH2O | ||

| Duration: 30 min | PSV | Duration: 2 h | ||

| PS: 0 | ||||

| PEEP 0 cmH2O Duration: 30 min | ||||

| VMNI | Not necessary | Alternated with CNAF | Recommendable | High risk |

HFNC: high flow nasal cannulas; BMI: body mass index; PEEP: positive end-expiratory pressure; PS: pressure support; PSV: pressure support ventilation; IMV: invasive mechanical ventilation; NIV: non-invasive mechanical ventilation.

After extubation of children considered high risk, it is recommended to use NIMV electively, before being used as a rescue technique due to the onset of respiratory failure, with the aim of reducing the reintubation rate21.

Conclusion

Knowledge and application of the SBT are considered one of the basic and necessary elements for evaluation within ICUs. Extubating a patient without adequate evaluation and performance of a SBT according to their characteristics could be considered bad practice. Further study is required to determine with more certainty the parameters necessary to adapt this test so that it fulfills its function of imitating post-extubation requirements. There are few exceptions for extubation without the need to perform a SBT, such as patients intubated for uncomplicated surgery with short-term MV.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)