Within the large group known as algae are grouped a set of organisms, of a very diverse nature, that share numerous similarities in their morphological and functional organization, reproductive processes, environments and distribution intervals, because of several convergences throughout their complex evolutionary history (Leliaert et al. 2014, Restrepo et al. 2016). They constitute an artificial classification, not a natural one; that is, it does not have a common ancestor, but rather a polyphyletic origin with multiple ancestors (Adl et al. 2012). Currently, new classifications based mainly on comparisons of ribosomal RNA sequences (Adl et al. 2012, 2019), support the phylogenetic relationship between a large section of this group (Glaucophyta, Rhodophyceae, and Cholorophyta) with embryophytes, within the supergroup Archaeplastida, being its diagnostic morphological character the acquisition of chloroplasts by primary endosymbiosis (De Clerck et al. 2012). However, other supergroups such as Stramenopiles (specifically the photosynthetic heterokonts of the division Ochrophyta), Alveolata or Excavata, whose chloroplast was acquired by secondary or tertiary endosymbiosis, group another large section of algal diversity such as Phaeophyceae, Diatomea, Dinoflagellata or Euglenida, among other minor groups, within the increasingly disused kingdom Protista (Bringloe et al. 2020). Additionally, within the term algae, the groups in incertae sedis Haptophyta and Cryptophyceae, with mixotrophic metabolism, are also considered (Nozaki et al. 2009, Adl et al. 2019).

Despite its polyphyletic nature, today the concept algae is conserved, with a utilitarian nature, to refer to a group of photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms that share a set of particular morphological, physiological and ecological characteristics that other groups do not present (van den Hoek et al. 1995). They can be unicellular, colonial or multicellular. They live in mainly aquatic environments, attached to a substrate (benthic), floating on the surface (neustonic) or suspended in the water column (planktonic). According to their size, they are also classified into macroalgae (seen with the naked eye) and microalgae (seen under a microscope). They are distributed in a great diversity of environments throughout the world, both continental and marine, being predominant in the latter, where they are responsible for about 50 % of the primary productivity on the planet (Guo et al. 2020). Additionally, they are ecosystem builders and shelters on which the development and nutrition of many vertebrates and invertebrates depend, as well as forming algal proliferations that can be toxic or harmful.

The diversity of marine algae known worldwide ranges from 17,500 to 18,000 species of macroalgae and 3,500 species of microalgae (Guiry 2024); some authors argue that there may even be an approximate diversity of 5,000 species of microalgae (Hernández-Becerril 2014). Although many species currently have a molecular basis that defines their identity and taxonomic independence (phylogenetic species or phylospecies), for the majority, within all algal groups, identification depends exclusively on morphology (morphospecies), resulting in a complicated or practically impossible task for many species, both due to the presence of high phenotypic plasticity and morphological monotony derived from a complex evolutionary history, shared among all of them, which generates overlapping characters, cryptic diversity and misidentifications (Cianciola et al. 2010). The above has not only led to the underestimation and/or overestimation of phycofloristic diversity, but also to several taxonomic problems at all hierarchical levels and, with it, the generation of unstable, not very robust classification systems that do not reflect the phylogenetic relationships between species (Leliaert et al. 2014).

In this regard, phylogenetic studies that incorporate molecular characters in the circumscription and discrimination of species constitute a fundamental component of biodiversity, since they allow their comparison with other specimens around the world and the obtaining of more robust hypotheses of interspecific relationship, without biases of interpretation of characters, allowing a better understanding of their evolutionary history (Preuss & Zuccarello 2024). Through understanding the processes that have produced changes in organisms over time (patterns), due to the action of evolutionary forces that act on genes, it is possible to understand the great biological diversity that we know today (Yi et al. 2023). The application of molecular tools, in all biological groups, has generated more stable classification systems and a better interpretation of the kinship relationships between species, as well as the evolutionary processes that they have faced (Cianciola et al. 2010). In this sense, the use of molecular characters in the study of Mexican marine algal diversity has provided solid evidence, which will be discussed later, to resolve different problems associated with the construction of this diversity exclusively on the morphospecies concept.

Marine algal diversity and the morphospecies problem

Mexico has an approximate coastline of 11,150 km (7,828 km from Pacific Ocean and Gulf of California and 3,294 km from Gulf of Mexico and Mexican Caribbean), plus 5,127 km2 of island edges (Lara-Lara et al. 2008, Pedroche & Sentíes 2020), with a great environmental heterogeneity and sites conducive to the establishment and development of a high diversity of benthic and planktonic marine algae, distributed in 17 coastal states (Dreckmann & Sentíes 2013). Currently, there is knowledge of a phycofloristic diversity made up of nearly 3,200 species of marine algae, recorded in both the Pacific and the Mexican Atlantic, approximately 1,500 species of microalgae (Hernández-Becerril 2014, Escárcega-Bata et al. 2023a) and 1,700 species of macroalgae (Pedroche & Sentíes 2020).

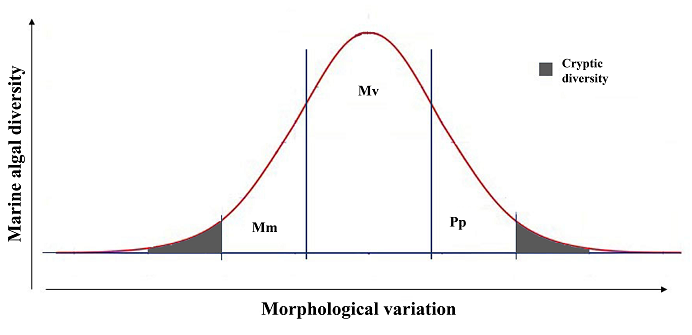

Much of biological work involves the recognition and discrimination of species, in order to achieve a better understanding of the diversity present in a given region. In this sense, the first approach to a phycoflora is based on the recognition of morphospecies, defined as the set of morphological attributes shared between a group of organisms that, generally, also share a geographic region (De Queiroz 2007). Although the number of phylogenetically supported species is increasing, current knowledge of the diversity of marine algae in Mexico, as well as their taxonomic classification, is based mainly on morphology (Pedroche & Sentíes 2003, Zamudio-Resendiz et al. 2022). The problem with morphospecies is that it depends on the phenotype that is expressed, from the genotype, in response to different environmental conditions. However, not all genotypes respond differentially to the environment, or not all environmental changes cause different phenotypes (Schilling & Pigliucci 2004). In this way, we can summarize the alternatives that a genotype has to express morphological variation (Pigliucci 2001) and the consequent problems associated with phycofloristic diversity as follows (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Hypothetical graphic representation of the distribution of marine algal diversity in the spectrum of morphological variation: Morphological Monotony (Mm), Morphological Variability (Mv) and Phenotypic Plasticity (Pp). The spectrum of cryptic diversity is represented in shadow.

Production of very similar phenotypes, associated with different genotypes. This is the case of phenotypically monotonous species, whose morphological differences are practically imperceptible to the naked eye, so it is common for them to go unnoticed among other similar species, generating an underestimation of phycofloristic diversity. In this interval (Figure 1, far left of the graph) numerous species of algae are found, such as those in the genera Alexandrium Halim, Bryopsis J.V. Lamouroux, Codium Stackhouse, Dictyota J.V. Lamouroux, Digenea C. Agardh, Euglena Ehrenberg, Gelidiella Feldmann & G. Hamel, Ulva Linnaeus or Ralfsia Berkeley, among many others (Pedroche 2001, León-Álvarez et al. 2014a, b, Lozano-Orozco 2014, 2015, 2016, Boo et al. 2018, Tufiño-Velázquez & Pedroche 2019, Vilchis et al. 2022b, Hernández-Becerril et al. 2023, Núñez Rasendiz et al. 2023). The problem of these species is easily detectable through the different floristic studies in which they are commonly reported as widely distributed or cosmopolitan species, since morphologically they are practically identical in all the environments in which they are established (Escárcega-Bata et al. 2022). Although they present certain morphological variations, they are very slight and are only detected until they are studied in detail, even so, the set of diagnostic characters available for their discrimination is limited.

Production of different phenotypes, clearly distinguishable from each other, associated with different genotypes (total genetic structure). This alternative corresponds to the true morphological variation associated with the species, allowing them to be clearly discriminated against each other by their morphological attributes, in any type of environmental conditions throughout their entire distribution range. These are the so-called good species, those that, when supported phylogenetically, can have a robust set of diagnostic characters that allow them to be easily recognized in the field, without confusing them with others (Cain 1956). In this interval we can find many species of seaweed (Figure 1, center of the graph) as in the genera Cymopolia J.V. Lamouroux, Codiophyllum J.E. Gray, Karenia Gert Hansen & Moestrup or Padina Adanson, among others (Díaz-Martínez et al 2016, Núñez Resendiz et al. 2020, Escárcega-Bata et al. 2024).

Production of several phenotypes, clearly distinguishable, associated with the same genotype. This alternative corresponds to phenotypic plasticity, which is the ability of the genotype to produce several phenotypes in response to different, or even the same, environmental conditions. In this way, a large number of organisms associated with the same genotype are often described as independent species or intraspecies on a morphological basis, generating not only the overestimation of biological diversity, but also the existence of several names associated with a species at the level of variety or form, which, on many occasions, after phylogenetic treatment, become part of a long list of names that are out of use, taxonomic synonyms or with uncertain taxonomic status. In this interval (Figure 1, far right of the graph), we find a large number of algae species, among which we can mention the species of the genera Caulerpa J.V. Lamouroux, Levanderina Ø. Moestrup, P. Hakanen, G. Hansen, N. Daugbjerg & M. Ellegaard, Minutocellus G.R. Hasle, H.A. von Stosch & E.E. Syvertsen, Sargassum C. Agardh or Tripos Bory, among many others (Fernández-García et al. 2016, González-Nieto et al. 2020, Hernández-Márquez et al. 2023). These species form large populations very well adapted to different environmental conditions, achieving wide distribution ranges.

Under the aforementioned, the problems of Mexican seaweed species associated with the morphospecies seem to be greater at the extremes of the spectrum of morphological variation (Figure 1), with morphological monotony and phenotypic plasticity being, by themselves, the main causes of underestimation or overestimation of algal diversity. Associated with these extremes, we find the case of cryptic species that are genetically independent but morphologically indistinguishable (Figure 1, shading), which directly contributes to the underestimation of phycofloristic diversity. In this sense, in algae are common cases in which the phenotypic expression between species is so reduced that morphologically they cannot be distinguished from others. A concrete example is found in Centroceras clavulatum (C. Agardh) Montagne in whose morphological spectrum there are 9 genetically independent species, hidden under the same phenotype, which, to this day, still cannot be discriminated as independent species (Won et al. 2009). Another example is found in the genus Pseudo-nitzschia H. Peragallo, from which numerous cryptic (without morphological characters that distinguish them from each other) and/or pseudocryptic (without limited morphological characters that distinguish them from each other, only visible after a morphological study in detail) species have been described (Lundholm & Moestrup 2002, Lundholm et al. 2012, Teng et al. 2015). At the other extreme, there are apparently highly phenotypically variable species, in which it is possible to recognize different phenotypes, even within the same population, so different from each other that they have been described as different species. However, this phenotypic plasticity is shared by other species within their distribution range, generating genetically independent species that express several overlapping phenotypes, so we find a case more similar to morphological monotony, despite the apparent high plasticity. This case is common in species with sympatric (shared) distribution, since the response of the genotype to the environment is the same, producing the phenotypes best adapted to those environmental conditions. Examples of these cases can be found in species of the genera Gracilaria Greville or Eucheuma J. Agardh (Gurgel et al. 2004, Núñez Resendiz et al. 2015, 2019a, Dreckmann et al. 2018, Vilchis et al. 2022a).

Under the theoretical support previously explained, from the use of molecular characters, it is possible to explain the hidden genetic diversity or structure (cryptic diversity) under the morphological monotony or phenotypic plasticity in algal populations, defining phylospecies and solving problems of underestimation and overestimation of marine algal diversity. However, despite its popularity in the last three decades and the fact that it is increasingly easier to obtain molecular sequences from PCR (Polymera Chain Reaction), in Mexico, there are few diversity studies that integrate a molecular support for the determination of phylospecies, or if this evidence is included, it is not discussed; consequently, the morphospecies continues to be weighted.

Phylospecies versus morphospecies in the Mexican phycoflora

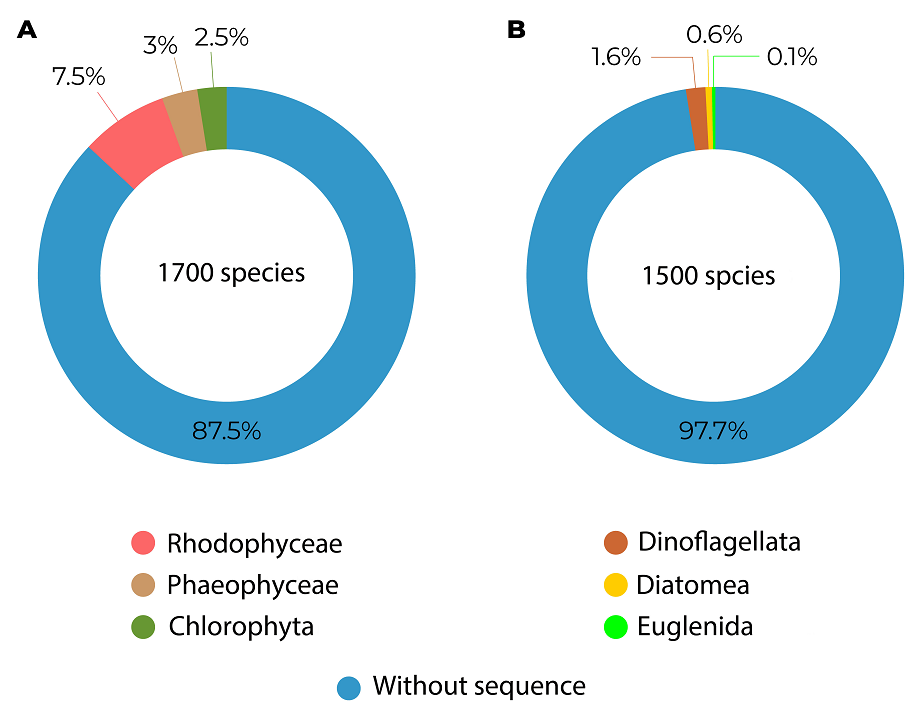

Of the diversity of Mexican marine algae currently recorded, nearly 1,700 species correspond to the three groups of marine macroalgae, being the red algae (Rhodophyceae) the most diverse with approximately 1,150 species, followed by the green algae (Chlorophyta) with about 310 species and the brown algae (Ochrophyta: Phaeophyceae) with 240 species (Pedroche & Sentíes 2020). In microalgae, with about 1,500 species recorded, the greatest diversity is concentrated in diatoms (Ochrophyta: Diatomea, Diatomista) with about 800 species, followed by dinoflagellates (Dinophyta: Dinoflagellata) with 650 species, Haptophyta with 58 species and minor groups such as euglenoids (Euglenozoa: Euglenida) with 5 species (Hernández-Becerril 2014, Escárcega-Bata et al. 2023a). The rest of the microalgae in Ochrophyta are not or poorly represented with less than three species (Hernández-Becerril 2014).

Macroalgae. Of the known diversity in Mexico, 87.5 % (1,488 spp) is based exclusively on the morphological basis, with only 12.5 % (211 spp) being those that, in addition to the morphological support, have a molecular identification (Figure 2A, Table S1). The most worked group at the molecular level is red algae, with 126 phylospecies belonging to 13 orders and 28 families (Appendix 1). The most studied groups have been Ceramiales, with sequenced representatives of 6 families, particularly for Ceramiaceae (with 25 phylospecies), followed by Gigartinales with 5 families represented, with Solieriaceae (with 5 phylospecies) being the most studied and Corallinales with 4 families represented, being Spongitidaceae (with 8 phylospecies) the most studied family (Appendix 1). However, the order Gracilariales is another widely studied group of red algae, considering that it is only represented by the Gracilariaceae family (with 13 phylospecies). Of the brown algae, with 50 phylospecies belonging to 4 orders and 5 families (Appendix 1), the most studied group is Dictyotales, family Dictyotaceae (with 24 phylospecies), followed by Fucales, family Sargassaceae (with 21 phylospecies). In green algae, being the least worked group, with 35 phylospecies belonging to three orders and seven families (Appendix 1), the most worked group was Bryopsidales, specifically the Codiaceae (with 12 phylospecies), followed by Halymedaceae (with 11 phylospecies), and Caulerpaceae (with 7 phylospecies).

Figure 2 Percentage of phylospecies versus morphospecies in phycofloristic diversity. A. Macroalgae with 1,700 species and the percentage of phylospecies in each group represented by different colors. B. Microalgae with 1,500 species and the percentage of phylospecies in each of the groups represented.

Microalgae. Of the known diversity in Mexico, 97.7 % (1,465 spp) is based exclusively on morphology, with only 2.3 % (35 spp) being those that, in addition to the morphological support, have a molecular identification that supports them as phylospecies (Figure 2B, Table S1). The best represented group at the molecular level are the dinoflagellates with 25 phylospecies, distributed in 6 orders and 10 families (Appendix 1), with Gymnodiniales, particularly Gymnodiniaceae (with 3 phylospecies), being the most studied. However, despite being represented by only one family, Gonyaulacales, particularly the Pyrocystaceae family (with 8 phylospecies), is the most worked on the group. In diatoms, with 9 phylospecies, belonging to 6 orders and 6 families (Appendix 1), the most worked group is Bacillariales, specifically Bacillariaceae (with 4 phylospecies), followed by the rest of the 5 families represented with only one phylospecies each (Appendix 1). As for the minor groups, there is only one phylospecies for Euglenophyta (Appendix 1, S1), from the order Ploeotiida and family Ploeotiidae. The rest of the phytoplankton groups in Mexico do not have molecularly supported species, they are all morphospecies.

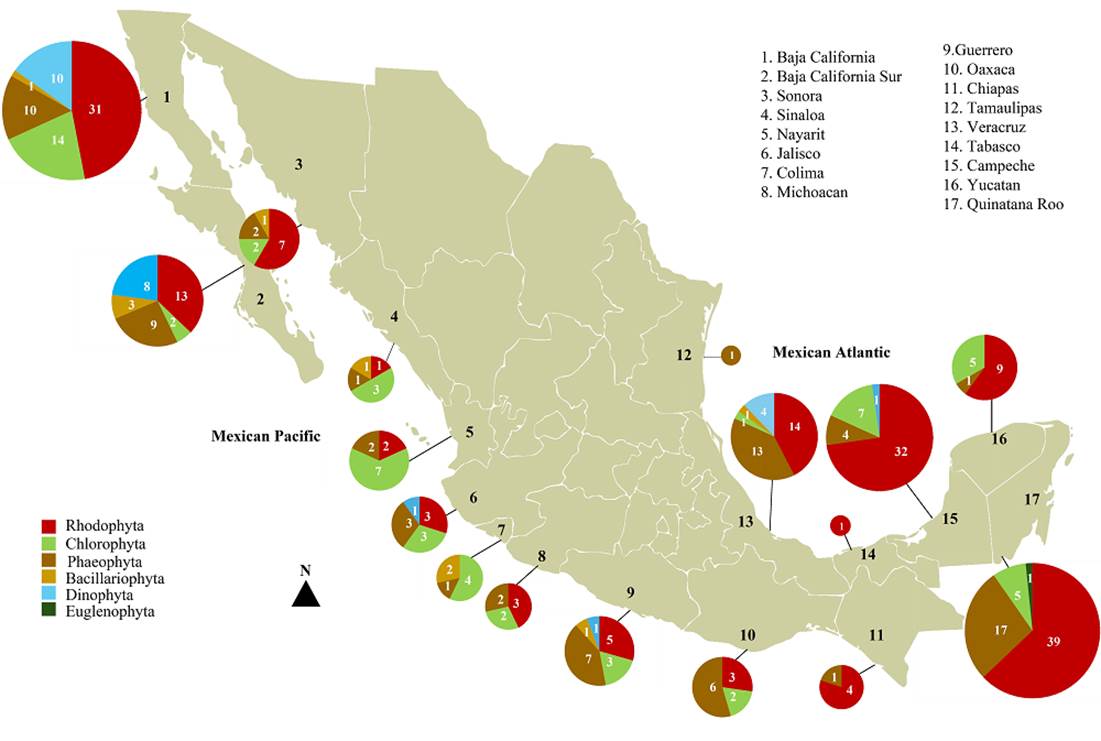

In both macroalgae and microalgae, phylogenetic studies have been carried out throughout the 17 coastal states of Mexico, sometimes with more than one specimen sequenced in different states for the same species and by different authors (Supplementary material Table S1), concentrating the most of them in the states of the Gulf of California, Gulf of Mexico and Mexican Caribbean region (Figure 3). In this sense, in the Mexican Pacific the states with the highest number of sequenced species are Baja California with 66 species, followed by Baja California Sur with 35 species, Guerrero with 17 species, Sonora with 12 species, Nayarit and Oaxaca with 11 species each, and Jalisco with 10 species; the least represented are Colima and Michoacán, both with 7 species, Sinaloa with 6 species and Chiapas with 5 species (Figure 3). In the Mexican Atlantic, the state with the highest number of sequenced species is Quintana Roo with 62 species, followed by Campeche with 44 species, Veracruz with 33 species and Yucatán with 15 species, while Tamaulipas and Tabasco only have one species each (Figure 3). It is notable that the states of the Mexican Atlantic have been worked on in a more homogeneous manner with respect to those of the Mexican Pacific, where a great difference is observed between those from the Gulf of California and the states of Central and Southern Mexico, with the exception of Guerrero, where about 70 % of the diversity of microalgae morphospecies recorded in Mexico is concentrated (Meave del Castillo et al. 2012) and a large number of macroalgae species (Pedroche & Sentíes 2020).

Figure 3 Map of Mexico showing the distribution and number of phylospecies per group of algae (represented with different colors) in each of the 17 coastal states. The difference in size of the graphs by state corresponds to the number of phylospecies it represents, with the largest sizes being those states that contain the greatest number.

Although some groups such as red, brown algae or dinoflagellates have been more widely studied than others, from a phylogenetic perspective, most of the work concentrates on a few genera of economic importance, both for the compounds of their cell walls such as agars, carrageenans or alginates, and for their ecological importance, as is the case of the Fucales species that constitute ecosystems for large animal species of economic importance, or the microalgae that form potentially toxic blooms. In the case of red algae, all species of the Laurencia J.V. Lamouroux complex, have been widely sequenced throughout the country, although mainly in the Mexican Caribbean region (Fujii et al. 2006, Cassano et al. 2009, Gil-Rodríguez et al. 2009, 2010, Mateo-Cid et al. 2014b, Sentíes et al. 2019). On the other hand, the species of agarophytes of the genus Gracilaria have also been widely studied, but most of the studies are concentrated in the Mexican Atlantic region (Núñez-Resendiz et al. 2015, 2017a, Dreckmann et al. 2018, Vilchis et al. 2022a). In the case of green algae, most studies focus on the genera Codium (Pedroche 2001, 2021), Bryopsis (Tufiño-Velázquez & Pedroche 2019) or Udotea J.V. Lamouroux (Acosta-Calderón et al. 2018), these last two concentrated in the Mexican Atlantic region (Figura 3). For brown algae, the most widely worked genera are Dictyota in the Gulf of California region (Tronholm et al. 2012, Vieira et al. 2021) and Gulf of Mexico (Lozano-Orozco et al. 2014, 2015, 2016), as well as Sargassum in this same region (González-Nieto et al. 2020) and Padina around all the Mexican coasts (Díaz-Martínez et al. 2016). In the case of diatoms, one of the most studied genera with molecular characters has been Pseudo-nitzschia for both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts (Lundholm & Moestrup 2002, Lundholm et al. 2012). In dinoflagellates, the western coast of Baja California has been worked emphatically (Figure 3), with species of the order Gymnodiniales, which contains many potentially toxic species (Escárcega-Bata et al. 2021), although also in Guerrero Karenia has been well worked and contain 8 toxic species from 10 known (Meave del Castillo et al. 2012, Escárcega-Bata et al. 2023a, 2024). However, the diversity represented by phylospecies in the 17 coastal states is notably scarce in contrast to the morphospecies recorded at a general level in each algal group and at a local level, in each of the states of Mexico (Hernández-Becerril 2014, García-García et al. 2020, 2021, Pedroche & Sentíes 2020, Escárcega-Bata et al. 2023a).

The phylospecies in the resolution of the problems of the morphospecies

Pedroche & Sentíes (2003) summarize the problems associated with Mexican marine algal diversity in three main aspects: (1) The limited number of characters for its delimitation, associated with its plastic nature or morphological monotony, which also overlaps with several unrelated phylogenetically groups, given their polyphyletic nature. The above has generated a large number of names that correspond to varieties or forms, or even to species not yet described. (2) The distribution of species based on their affinity for temperate and/or tropical regions and the convergence of this distribution, generating identity problems associated with their biogeography or differential sampling, and, consequently, differential diversity between the different regions. (3) Presence of presumably invasive species and the lack of historical studies that allow evaluating the impact of their introduction to the native flora.

Diversity studies using phylogenetic methods have been successfully implemented for the characterization of phylospecies, directly contributing to a better understanding of algal diversity and its evolutionary relationships, mainly in the species detected in the spectrum of morphological monotony or the phenotypic plasticity, providing a solution to the problem described above. Particularly for the Mexican phycoflora, there are 250 phylospecies within all algal groups, contained in 142 studies carried out throughout the 17 Mexican coastal states (Appendix 1). In general, with the recognition of these phylospecies, it has been possible to strengthen phylogenetic hypotheses through the description of new species (Mateo-Cid et al. 2005, 2012, 2014a, b, Mendoza-González et al. 2011, Lozano-Orozco et al. 2015, 2016, Olivares-Rubio et al. 2017, Sentíes et al. 2014, 2016, 2019, Núñez Resendiz et al. 2017b, 2019a, 2020, 2023, Dreckmann et al 2018, Quiroz-González et al. 2020, 2021a, 2024, Sauvage et al. 2021), description of new genera (Cassano et al. 2012, Núñez Resendiz et al. 2018), new nomenclatural combinations (Díaz-Larrea et al. 2007, Sentíes & Díaz-Larrea 2008, León-Álvarez et al. 2014b, Núñez Resendiz et al. 2019b), cryptic diversity recognition (Hind et al. 2014, Filloramo & Saunders 2018), distribution patterns (Boo et al. 2018, Hernández et al. 2020, 2021), conspecific species with the consequent reduction in diversity (Cassano et al. 2009, Fernández-García et al. 2016, González-Nieto et al. 2020), new records for an area (Lozano-Orozco et al. 2014, Godínez-Ortega et al. 2018, Escárcega-Bata et al. 2021, 2024, Vilchis et al. 2022a, Díaz-Martínez et al. 2023, Hernández-Márquez et al. 2023), resurrection of species (Broom et al. 2002, Cho et al. 2003a, Andrade-Sorcia et al. 2014, León-Álvarez et al. 2014a), expansion or delimitation of distribution intervals (Calderon et al. 2021, Lora-Vilchis et al. 2021, Pedroche 2021, Vilchis et al. 2022b, Hernández-Becerril et al. 2023), confirmation and morphological characterization of previously recorded species (Band-Schmidt et al. 2008, Díaz-Martínez et al. 2016, León-Álvarez et al. 2017, Quiroz-González et al. 2021b, Morquecho et al. 2022, Durán-Riveroll et al. 2023) or detect endemic or introduced diversity (Riosmena-Rodríguez et al. 2012, García-Rodríguez et al. 2013, López-Vivas et al. 2015).

It is important to highlight that, despite the importance of phylospecies in diversity studies, there must be a good morphological characterization that allows their discrimination, since morphology will never be separated from the species, because this is the result of genetic expression and what allows us to recognize species in their natural environment. However, the morphological criterion should not predominate over the genetic one, since it is the genes that determine morphology and as discussed previously, morphology presents different aspects that have generated problems in the current classification systems of all groups of algae. Additionally, is important to be in account that many species present wide ranges of distribution, which correspond with different biogeographic provinces (Spalding et al. 2007, Wilkinson et al. 2009) and, consequently, with heterogeneous environments in which the phenotype is being expressed. In this sense, of the 250 phylospecies presented (Appendix 1 and Table S1), not all have an adequate phylogenetic treatment, that is, many Mexican specimens were sequenced as part of studies whose objective was not the treatment of Mexican species, therefore, no mention is made of their morphological attributes or phylogenetic relationships (Table S1). In this case, 36 of 126 red algae, 7 of 35 green algae and 5 of 50 brown algae were found (Table S1); The rest of the species presented are associated with references that include detailed morphology of the Mexican species, including all microalgae (Appendix 1). In microalgae, it is also common to find in molecular databases sequences from sites in Mexico that were obtained from metagenomics; however, they are not associated with a particular morphology or reference, which is why they were not included in this review. Of the 142 references that incorporate phylogenetically and molecularly supported species, 91 have detailed morphological mentions of the Mexican specimens (Appendix 1). However, it is important to note that, between the literature revised, we detected several cases in which, despite molecular sequences are presented with morphological studies about the Mexican species, these studies do not present phylogenetic interpretations about the results founded, it means, the sequences presented were not compared with those related from the GenBank or phylogenetic relationships were not described (Vázquez-Delfín et al. 2016, Acosta-Calderón et al. 2018, Tufiño-Velázquez & Pedroche 2019); so, although morphological results are accompanied by molecular characterization, without these comparisons species cannot be considered true phylospecies. In this sense, it is necessary to evaluate them and determine their true phylogenetic position. On the other hand, of the 91 references in which the morphology is described in detail, 82 had important changes for the Mexican phycoflora (Appendix 1), referred to above, such as description of new diversity, new records, detection of cryptic species, redefinition of distribution intervals, new combinations and/or arrangements or decrease in diversity. These changes reveal that, with Mexico being such a heterogeneous country in the marine environment, the currently known diversity, based on the morphospecies, is subject to change drastically with the definition of the phylospecies, mainly in terms of estimates and general conception of the Mexican phycofloristic composition.

Final considerations

Although in Mexico there have actually been few morphospecies of marine algae confirmed molecularly, the number of specialists training in this line is increasing. Part of its limited use may be due to the fact that it requires more complicated analysis methodologies for which greater dissemination would be necessary, which could be in the form of refresher courses. On the other hand, there are studies in which large sampling and greater economic investment are required, both due to the number of sequences that are generated and the number of sites that must be sampled, so their development requires the support of large projects; for its financing. However, the use of molecular markers is much cheaper and more reliable as the years go by, and it is relatively easy to obtain sequences at a low cost. Another relevant aspect to consider is that, in the characterization of the phylospecies, we seek to provide explanations for the problems previously exposed, based on the description of the evolutionary processes responsible for their current distribution and relationships. However, in Mexico we are faced with the problem of restricted access, due to security issues, to a considerable proportion of localities that make up the distribution range of many species, which can generate biases in the characterization and phylogenetic interpretations.

Finally, the high number of studies that characterize phylospecies in macroalgae, with respect to microalgae, is notably evident. Much of this difference may be due to the fact that, although phylogenetic evidence has been better incorporated in the definition of macroalgae species, in the case of microalgae the morphological criterion continues to predominate over molecular evidence (Zamudio-Resendiz et al. 2022), therefore, the use of phylogenetic analyzes in these organisms is still limited. In addition, it should be considered that the primers used can be applied to all phytoplankton groups, which does not adequately resolve relationships between species (Escárcega-Bata et al. 2023b). However, it is expected that in the future the characterization of a greater number of phylospecies in studies of marine algal diversity will increase and be uniform in both groups, in order to better understand the principles and processes associated with their establishment and development on the Mexican coastlines and oceans, which allow to implement correct management of this resource and its conservation.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here: https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.3584.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)