Introduction

Investing in early childhood development is a key strategy to reduce social disparities, strengthen the economy, and build more equitable societies. Moreover, early childhood development is one of the most important health determinants, with effects that persist throughout life. According to James J. Heckman, Nobel Laureate in Economics, and different studies, investing in early childhood education is a cost-effective strategy for driving economic growth, with a return of at least $7 for every dollar invested in high quality interventions1-6.

Child development remains a significant challenge for countries in Latin America, including Mexico. Achieving healthy development requires creating the right conditions to ensure that children grow holistically in physical, socio-emotional, and linguistic-cognitive aspects7.

In this context, the Health Ministry in Mexico has implemented developmental mandatory assessments at the primary care level to identify developmental risks and warning signs in the national norm NOM-1999-031-SSA28. After the review of evidence for a National expert panel conducted in 20129, the Health Ministry has incorporated the use of the Child Development Evaluation test (CDE test) or in Spanish Prueba Evaluación del Desarrrollo Infantil (Prueba EDI) as the national screening tool for every children younger than 5 years old10, a screening tool designed and validated in the country for the early detection of neurodevelopmental issues in children under the age of 5 years11 in 2011, given the importance of early intervention in children in that period of age12,13 This test helps confirm the developmental progress of healthy children and identifies those with delays or problems relative to their age, assessing through 14 different groups the developmental milestones from birth to age five. It was designed to provide a reliable and easy-to-administer instrument for use at the primary healthcare level14,15.

Although significant progress has been made in this area in recent years, a comprehensive public policy, supported by cost-effectiveness studies, is still needed to implement optimal interventions within the Mexican context, and to reinforce the use of standardized screening tools across the Whole Health Sector.

The aim of this study is to analyze the cost-effectiveness of the CDE test compared to standard medical consultation in Mexico using a simulation model.

Methods

The study was conducted with the information available until 2020. A cost-effectiveness analysis was conducted from the perspective of the public and social sectors in Mexico. The study employed a decision tree model to evaluate the strategies. The time horizon was set at 1 year; therefore, no discounting was applied.

Costs were calculated in Mexican pesos (MXN) at 2019 prices and included both direct and indirect costs. Direct costs encompassed CDE test administration, specialist consultations, and rehabilitation sessions, while indirect costs considered transportation expenses and lost wages related to caregiving16.

Effectiveness was defined as the proportion of children correctly screened for neurodevelopmental issues, with the Battelle Developmental Inventory-2 (BDI-2) serving as the reference standard for comparison.

Statistical model

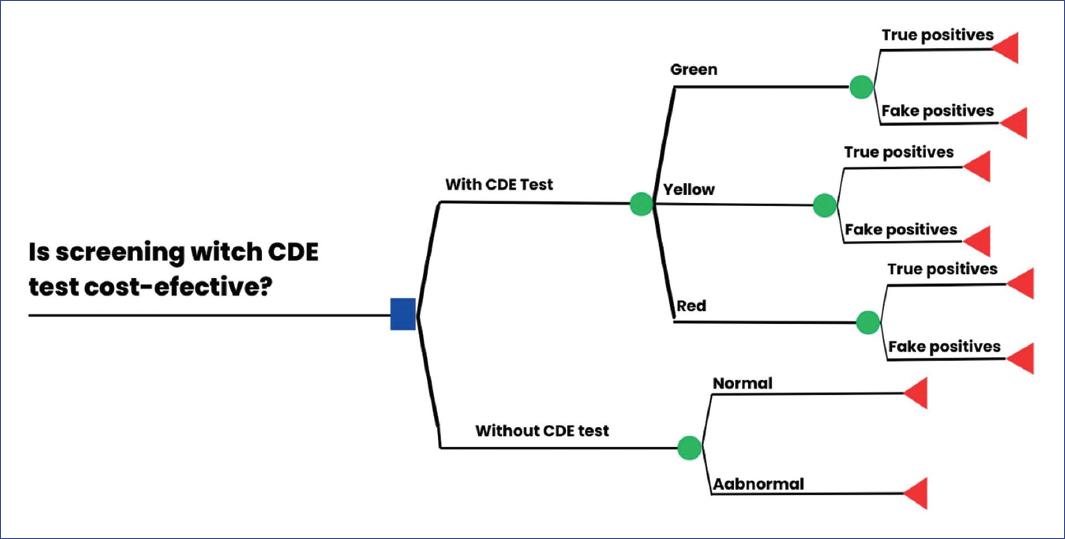

The graphical representation of the statistical model is depicted in the decision tree (Fig. 1). The model starts with a square symbol, representing the key question to be answered. The first two branches divide the population into two groups: individuals assessed with the CDE test and those assessed without the CDE test. This is followed by a probability node (green circle).

Figure 1 The decision tree for screening child development with and without child development evaluation test.

For the branch representing the group assessed with the CDE test, subsequent branches classify outcomes based on developmental categories: green, yellow, and red. Each category leads to a probability node that distinguishes between true positives and false positives. These probabilities are derived from the ability of the CDE test to identify developmental status when compared to the BDI-2, which serves as the reference for evaluating the test's effectiveness.

The identification of test outcomes is quantified using predictive values:

− True positives: cases accurately identified by the test.

− False positives: cases incorrectly identified by the test, belonging to a different developmental category.

Each branch includes the probability distribution of the category, while the complementary probability (forcing the sum to equal 1) is assigned to the other branch originating from the same node.

In the branch representing individuals assessed without the EDI test, the probability node is divided into two outcomes: cases categorized as having normal development and those categorized as abnormal.

Finally, all branches of the decision tree terminate at red triangles, which represent the resulting distributions for cost and effectiveness.

To account for variability and uncertainty, a Monte Carlo simulation with 10,000 iterations was performed. In addition, a probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) was conducted to test the robustness of the results. The analysis was executed using the TreeAge Pro Healthcare 2019 software.

Ethically, the study was classified as minimal risk, aligning with established guidelines for research involving human populations, there were no personal information used, and all was based in the public data available. This study was approved and registered in the ethics committee from the Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez (HIMFG) as a thesis17.

Results

Transition probabilities were estimated based on a review of the literature and validation studies of the CDE test and are shown in table 115,16,18-21. This analysis demonstrates that the CDE test is a dominant strategy compared to standard medical consultations, as it is both more effective and less costly, as is shown in table 2.

Table 1 Parameters included in the decision tree model for child development screening in Mexico

| Parameters | Base Cost ($, MXN) | References | SA1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct costs*2 | |||

| Cost per test application consultation | $115 | [A] | ±50% |

| Cost per CDE test*2 | $ 6.5 | [B] | ±50% |

| Cost per specialty consultation | $ 115 | [A] | ±50% |

| Cost per rehabilitation session | $ 115 | [A] | ±50% |

| Indirect CostI*2 | |||

| Travel for medical care | $ 89 | [A] | ±50% |

| Travel for rehabilitation session | $ 89 | [A] | ±50% |

| Salary lost per day of medical consultation and/or rehabilitation session | $38.5 | [C] | ±50% |

| Transition probabilities | |||

| With EDI test | |||

| Green | 0.81 | [D] | (0.75 0.86) |

| True positives | 0.94 | [E] | |

| False positives | 0.06 | [E] | |

| Yellow | 0.15 | [D] | (0.11-0.16) |

| True positives | 0.88 | [F] | |

| False positives | 0.12 | [F] | |

| Red | 0.04 | [D] | (0.02-0.05) |

| True positives | 0.94 | [F] | |

| False positives | 0.06 | [F] | |

| Without EDI test | 0.71 | [G] | (0.28 0.33) |

| Normal | 0.29 | [G] | |

| Abnormal |

*1 SA, Sensitivity analysis.

*2 Costs are presented in Mexican pesos (MXN), one US dollar (USD) is equivalent to $19.56 MXN.

[A] Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez 2019 Fee Schedule16.

[B] Estimated based on the unit cost of $86.76 MXN, the use of a manual for every 15 tests applied plus the unit cost of the pencil for the application of the test.

[C] Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare. CONASAMI. Estimated based on the minimum wage in Mexico 2019, $102.68 MXN18.

[D] Rizzoli-Córdoba, et al. Population-based screening of the level of child development in children under 5 years of age who benefit from PROSPERA in Mexico19.

[E] Rizzoli-Córdoba A, et al. Convenio CNPSS-Art 1º-025-2014 "Evaluación diagnóstica y perfil de desarrollo en niños menores de cinco años identificados con riesgo de retraso en población afiliada al Seguro Médico Siglo XXI. 201515.

[F] Rizzol-Córdoba i, et al. Reliability of the detection of developmental problems using the traffic light of the child development assessment test: is a yellow result different from a red one?20.

[G] De Castro, et al. Indicators of child well-being and development in Mexico21.

Table 2 Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio per adequately screened child with CDE test

| Strategy | Costs in MXN pesos (mean) | Incremental cost (∆C) | Effectiveness (mean) | Incremental effectiveness (∆E) | ICER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With CDE test | $7,326 | −3,943 | 0.60 | 0.01 | - |

| Without CDE test | $11,269 | - | 0.59 | - | Dominada |

ICER: incremental cost-effectiveness ratio. CDE test: child development evaluation test or prueba EDI in Spanish.

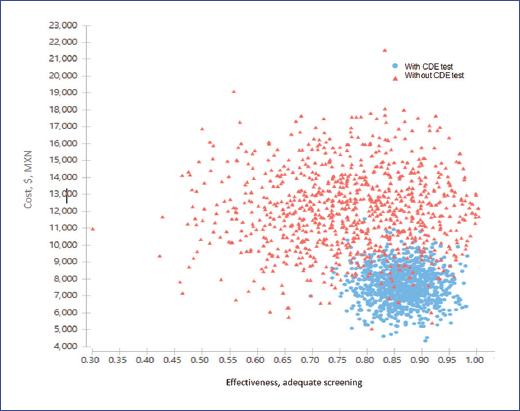

In figure 2, the cost-effectiveness plane highlights the distributions of children screened with and without the CDE test. More than 50% of iterations indicate that the CDE test is cost-saving, demonstrating its potential to reduce economic burden while achieving greater health outcomes.

Figure 2 Graphical representation of the cost-effectiveness distributions of screening with and without testing.

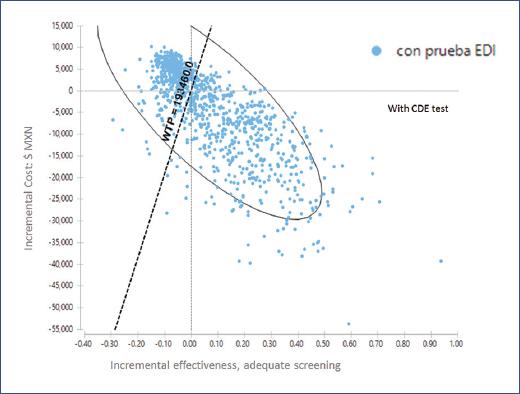

Figure 3 further illustrates the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) through the distribution of incremental costs and incremental effectiveness associated with the CDE screening strategy. The results confirm that the CDE test consistently outperforms the standard approach, delivering improved outcomes at reduced costs in most scenarios. In addition, the strategy is well within Mexico's willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold, reinforcing its feasibility and economic justification for implementation.

Figure 3 Distribution of incremental effectiveness and incremental cost of screening with child development evaluation test. The willingness to pay (WTP) is included, which is equivalent to a GDP per capita for Mexico ($193,460 MXN, 2019).

The incremental net monetary benefit (INMB) of implementing CDE screening was $44,608 MXN (2019 value), providing additional evidence of its cost-effectiveness.

Discussion

In this study, a cohort of 10,000 children was simulated. All these children could be screened to assess their neurodevelopment and enable targeted interventions4,22,23.

During the first 5 years of life, children face a higher likelihood of developmental delays or risks, as these years are critical for their overall performance later in life. The presented scenarios compare two options: screening with the CDE test versus routine medical consultations without a specific screening tool. In the latter case, inadequate identification of developmental risks may occur, potentially missing opportunities for timely intervention. Early detection and specific interventions can reduce developmental delays and maximize children's potential24-26.

The costs associated with the CDE screening strategy were lower than those without it. This difference is likely due to the high opportunity cost of failing to identify children at risk or already experiencing developmental delays24-27.

Effectiveness was measured by the number of children correctly screened. A decision tree incorporated probabilities for correct identification within the EDI test classification categories: green, yellow, and red, representing normal development, risk of delay, and developmental delay, respectively, compared to results obtained with the IDB-2. The results demonstrated that the CDE screening strategy was dominant, being both less costly and more effective (in terms of correct identification) than the alternative16,28.

Furthermore, the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve indicated that 100% of the simulations were cost-effective under the presented model. While the use of ICER in decision-making remains debated due to the need for extensive, reliable data, the INMB and incremental net benefit in health offer alternative decision parameters. The implementation of CDE screening, as the cost required to achieve the benefit was lower than the maximum willingness to pay for such a benefit18.

Uncertainty was addressed through PSA, providing decision-makers with guidance under uncertain conditions and supporting the implementation of the CDE test. In Mexico, funding for strategies and interventions depends on decision-makers' willingness to pay. Proper use of cost-effectiveness analyses is a valuable tool for evaluating resource allocation and optimizing healthcare spending amid increasing constraints.

From a rights-based perspective, every child has the right to reach their full potential. Systematic evaluation ensures equal detection opportunities and equitable access to interventions for at-risk children. It also facilitates continuous improvement efforts and impact assessments20,21,29-31.

Promoting strategies that position childhood well-being, including developmental evaluations, on the political agenda are essential for evidence-based decision-making. Such strategies can significantly enhance the quality of life and well-being of children in Mexico32,33.

Study limitations

The study faced several limitations. The inherent uncertainty of the model and its parameters could impact the results. Costs are constrained by temporal monetary value changes, the costs were calculated with the evidence available and published in 2019 and until today more information is needed to improve the analysis. The model assumes the CDE test focuses on detecting developmental delays but spans multiple domains, and effectiveness was considered constant across ages despite potential variability. Future studies should evaluate the cost-effectiveness of CDE across age groups and specific domains, as well as the long-term sustainability of its demonstrated effects.

Conclusion

In Mexico, this study suggests that the CDE test is cost-saving from the public and social sector perspective, generating a net increase in both monetary benefits and health outcomes. Furthermore, its implementation is feasible within the Mexican healthcare system, particularly considering its potential to enhance efficiency in the long term. In addition, its inclusion represents a significant opportunity as a social policy for children, aligned with a rights-based approach. More studies are needed to get better information to be able to have a better estimate of both economic and health benefit.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)