INTRODUCTION

Over half of the reefs across the world are estimated to have been lost over the past 30 years, and they are currently in a state of crisis (Downs et al. 2005, Souter et al. 2021). The main factors contributing to coral reef degradation include urban and industrial development in coastal areas, agricultural activity, sedimentation, overfishing, marine pollution, and climate change, which leads to ocean warming and acidification (Bindoff et al. 2019, Obura et al. 2019, Souter et al. 2021, Feng et al. 2023). Furthermore, climate change has increased the incidence of coral diseases (Gil-Agudelo et al. 2009; Alvarez-Filip et al. 2019, 2022), and, unlike past climate events, such as those of the Paleocene, the current accelerated pace of global warming (Zeebe et al. 2016) is affecting the adaptive and resilience capacity of corals.

The year 2023 was marked as the warmest year on record, possibly in the last 100,000 years of the Earth, triggering the most severe coral bleaching and mortality event reported in the Northern Hemisphere and the Caribbean region (Goreau and Hayes 2024, Schmidt 2024). Nevertheless, 2024 had the highest ocean temperatures recorded in the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, posing a threat to coral communities in this region (Henley et al. 2024, Tollefson 2024). As a result, the biodiversity of reefs and associated communities has changed. Thus, baseline assessments and ongoing monitoring are needed to determine the health of these ecosystems, which will facilitate the design of effective management and conservation strategies (Downs et al. 2005, Obura et al. 2019).

In Mexico, reef health assessments have been carried out over the years, both for the reefs of the southwestern Gulf of Mexico (SGM; Horta-Puga 2003, López-Padierna 2017, Arguelles et al. 2019, Pérez-España et al. 2021) and for the reefs of the Mexican Caribbean (MC; Ruiz-Zárate 2003; HRI 2008; Caballero-Aragón et al. 2020a; McField et al. 2022, 2024), using different methodologies. The Reef Health Index (RHI) has been widely used in MC reefs. This index was implemented by the Healthy Reefs Initiative (HRI) and is one of the first regional efforts to develop reef health criteria and indicators.

Since 2008, the HRI has produced biennial reports on reef health in the region (HRI 2008; Kramer et al. 2015; McField et al. 2022, 2024), which have provided insight into the status and trends of reefs over time and the progress of restoration and conservation efforts in the MC and, on a larger scale, the Mesoamerican Reef System (MAR). However, the need to apply the RHI at more sites in the MC has been highlighted (Díaz-Pérez et al. 2016); furthermore, its expansion to reefs in the SGM has been proposed, as reef health assessments based on scoring systems are still limited in this region, with those carried out by Simoes et al. (2020) and Pérez-España et al. (2021) being particularly noteworthy.

In Mexico, the most important reefs, in terms of size and diversity, are those found in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean (Horta-Puga et al. 2019). These reefs provide ecological, environmental, and economic services (SENER 2016); in addition, they serve as the connection with the rest of the coral ecosystems of the Wider Caribbean (Tunnell et al. 2007). Veracruz reefs have been considered one of the most threatened in the Wider Caribbean (Horta-Puga 2003, Pérez-España et al. 2015) because they have been exploited for centuries (López-Padierna 2017). Despite not being abundant, their uniqueness, isolation, and good state of conservation make these reefs highly relevant for research and preservation (Gil-Agudelo et al. 2020).

On the other hand, the MC hosts the most extensive reef formation in Mexico, mainly composed of fringing reefs that extend more than 350 km along the coast of the state of Quintana Roo (Ruiz-Zárate et al. 2003, Ardisson et al. 2011, Blanchon 2011). These reefs have experienced continuous devastation since the early 1980s due to anthropogenic activity in the region (Pérez-Cervantes et al. 2017).

Therefore, this study aimed to assess the health status of 11 reef sites in the SGM and MC to elucidate their current condition and evaluate the effectiveness and applicability of the RHI in these 2 regions. It also enabled the analysis of the main factors that could influence their health status, such as the natural history and demographics of both regions. Finally, the results for each of the indicators used and the RHI score will serve as a reference point prior to the severe bleaching event of 2023.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

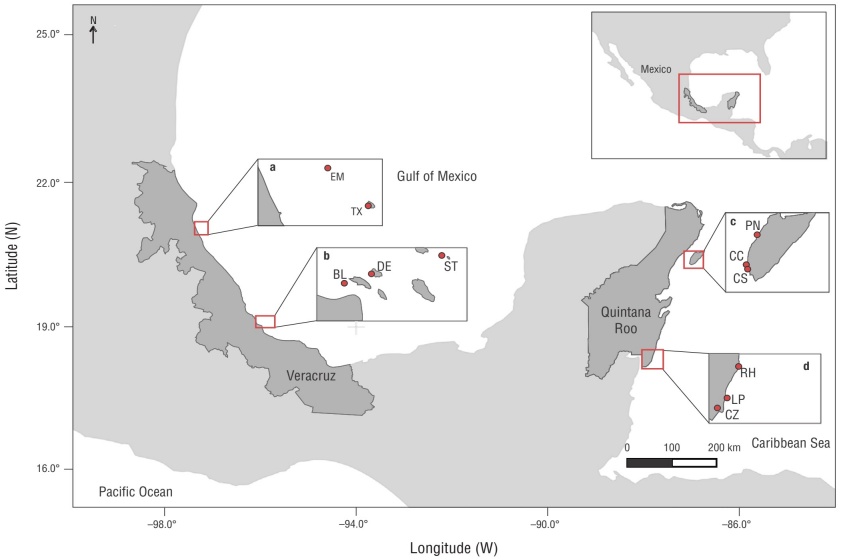

The sampling sites for this research covered 2 regions of the Mexican Atlantic: SGM and MC. The reefs of SGM are located off the coast of the state of Veracruz (Tunnell et al. 2007). One of the reef systems in this region is the Flora and Fauna Protection Area Sistema Arrecifal Lobos-Tuxpan (APSALT, for its acronym in Spanish), located north of Veracruz. It encompasses 6 emergent and platform-type coral formations divided into 2 subsystems or polygons: north and south (González-Gándara et al. 2013, Ortiz-Lozano et al. 2013, Cancino-Guzmán 2018).

The Sistema Arrecifal Veracruzano National Park (PNSAV, for its acronym in Spanish) is the largest reef complex in the SGM (Chávez et al. 2007), located south of Veracruz (SEMARNAT 2017). This system encompasses approximately 50 coral reefs, of which half are emergent (fringing or platform; Ortiz-Lozano et al. 2013, Robertson et al. 2019) and the rest are submerged (Ortiz-Lozano et al. 2019), distributed in 2 groups: north and south (Horta-Puga et al. 2015, Pérez-España et al. 2015).

The MC region is part of the MAR and extends 400 km along the coast of the state of Quintana Roo (Rioja-Nieto and Álvarez-Filip 2019), from Isla Contoy and Cabo Catoche in the north, to Xcalak and Banco Chinchorro in the south (Carricart-Ganivet and Horta-Puga 1993, Chávez-Hidalgo 2009). Among others, this region encompasses the systems Arrecifes de Cozumel National Park (PNAC, for its acronym in Spanish) in the northern zone and the Arrecifes de Xcalak National Park (PNAX, for its acronym in Spanish) in the southern zone.

For the APSALT, we selected the Tuxpan and Enmedio reefs (Fig. 1), which are both located within the Tuxpan subsystem in the southern portion and are emergent and platform-type reefs, respectively (González-Gándara et al. 2013, Ortiz-Lozano et al. 2013). In the PNSAV, we selected the Blanca, De Enmedio, and Santiaguillo reefs (Fig. 1), all located in the southern group (Horta-Puga and Tello-Musi 2009); like those in the APSALT, they were all emergent and platform-type reefs (Ortiz-Lozano et al. 2013).

Figure 1 Map illustrating the study area and sampling sites: southwestern Gulf of Mexico (SGM) and Mexican Caribbean (MC). Lobos-Tuxpan Reef System Flora and Fauna Protection Area (APSALT, for its acronym in Spanish) (a); Sistema Arrecifal Veracruzano National Park (PNSAV, for its acronym in Spanish) (b); Arrecifes de Cozumel National Park (PNAC, for its acronym in Spanish) (c); Arrecifes de Xcalak National Park (PNAX, for its acronym in Spanish) (d); Tuxpan (Tx); Enmedio (EM); Blanca (BL); De Enmedio (DE); Santiaguillo (ST); Paraíso Norte (PN); Caracolillo (CC); Colombia Somero (CS); Huach River (RH); La Poza (LP); Zaragoza Channel (CZ).

The reefs selected for the PNAC were Caracolillo, Paraíso Norte, and Colombia Somero, located both in the northern and southern extremes of the National Park (Fig. 1). These reefs are classified as fringing (Fenner 1988, Jordán-Dahlgren and Rodríguez-Martínez 2003) and insular (Rioja-Nieto and Álvarez-Filip 2019). For the PNAX, the Río Huach, La Poza, and Canal de Zaragoza reefs were chosen as study sites (Fig. 1) to encompass the extremes of the National Park. Río Huach, in the northern zone, is considered a nursery area for fish and marine invertebrates of ecological and commercial importance, whereas the Canal de Zaragoza, in the south, is identified as a vessel entry zone (Villegas-Sánchez et al. 2023). These are all considered fringing reefs (Weidie 1985, Jordán-Dahlgren and Rodríguez-Martínez 2003, Arias-González et al. 2008).

We chose to sample the leeward zone on all reefs in the SGM and CM (Jordán-Dahlgren and Rodríguez-Martínez 2003, Hongo and Kayanne 2009) to ensure similar exposure conditions. This zone has been recorded as having the greatest coral development in the APSALT and PNSAV (Lara et al. 1992, Escobar-Vásquez and Chávez 2012, Horta-Puga et al. 2015, González-González et al. 2016) and in the PNAC and PNAX (Fenner 1988). Samplings were carried out at depths between 7 and 12 m to minimize variations in environmental conditions such as light and temperature, which influence coral cover.

The composition of these reefs on a broad geographic scale, such as the Mexican Atlantic, is considered similar and has 3 main structural zones: fore reef, reef crest, and back reef (Jórdan-Dahlgren and Rodríguez-Martínez 2003). This zonation is primarily determined by wave impact, light, and depth (Escobar-Vásquez and Chávez 2012, Rioja-Nieto and Álvarez-Filip 2019).

Fieldwork

Sampling was done in October 2022 in the SGM and in May 2023 in the MC. At each sampling site, 5 or 6 replicates were done to assess each indicator of interest (fishes and benthic organisms). Fish sampling was carried out using visual surveys using scuba equipment and 50 × 2 m transects (Díaz-Pérez et al. 2016). The species, size, and abundance of all observed fish were recorded on each transect. To characterize the benthic structure, 50 × 0.50 m video transects were recorded with the aid of an underwater camera over the same fish transects (Díaz-Pérez et al. 2016). A GoPro Hero8 camera (GoPro, San Mateo, USA) was used in standard mode and 4K 4:3 resolution.

Estimation of health indicators

Coral and algal covers were calculated from field-recorded videos, from which 40 photographs per transect were selected for analysis using 13 fixed points (Villegas-Sánchez et al. 2015, Barrera-Falcón et al. 2021). Photographs for each video were automatically captured using VLC Media Player v. 3.0.18 Vetinari (VLC Media Player, Inc., Paris, France), setting time intervals according to the length of each video. Photo analysis was carried out using the AEFEBE v. 1.1 software (Lara-Arenas and Villegas-Sánchez 2016) on a Linux operating system. Under each fixed point, predetermined by the software, the substrate type was identified, including coral and fleshy macroalgae cover, following a modification of the method described by Aronson et al. (1994). The guides of Humann and Deloach (2013) and Vargas-Hernández et al. (2017) were used to identify hard coral species.

The biomasses of herbivorous fishes from the families Scaridae and Acanthuridae and commercial fishes from the families Lutjanidae and Serranidae were calculated using the length-weight relationship equation (Equation 1):

where W is the total weight of the fish, L is the total length, a is the coefficient scale, and b is the parameter determining fish body shape (Kuriakose 2014). The parameters a and b were obtained from FishBase (Froese and Pauly 2023).

Reef health index (RHI)

Finally, we estimated the RHI, which considers 4 indicators: live hard coral cover, fleshy macroalgae cover, herbivorous fish biomass, and commercial fish biomass (HRI 2012; McField et al. 2022, 2024). Reef-building hard corals were considered for the live coral cover. This is an important indicator since these corals are responsible for the structural complexity of reefs, fish abundance, and overall diversity in reef ecosystems (Graham and Nash 2013).

Large, soft algae, such as species from the genera Dictyota, Lobophora, Halimeda, and Sargassum, were included for the macroalgae cover (Delgado-Pech 2016). These fleshy macroalgae are associated with coral reef degradation because they compete with corals for space, negatively impacting larval settlement and adult coral survival (Adam et al. 2015, Ceccarelli et al. 2020, Quezada-Pérez et al. 2023).

The RHI considers the families Scaridae and Acanthuridae for the herbivorous fish biomass because these reduce the amount of fleshy macroalgae. For commercial fish biomass, it considers the families Lutjanidae and Serranidae due to their commercial importance and their trophic role as carnivores (McField and Kramer 2007). Indicator ratings and scores were based on the criteria and thresholds established by McField et al. (2024) (Table 1) for the MAR. This standardized assessment allowed us to evaluate the health status of the SGM and MC and understand the performance of these criteria in the SGM.

Table 1 Criteria and thresholds established for each of the 4 indicators of the reef health index. Values taken from McField et al. (2024). Coral and fleshy macroalgae cover in percentage and biomass of herbivorous and commercial fish in grams per 100 m2.

| Score | Coral cover (%) | Fleshy macroalgae cover (%) | Herbivorous fish biomass (g·100 m-2) | Commercial fish biomass (g·100 m-2) |

| Very good (5) | 40 | 1 | 3,290 | 1,620 |

| Good (4) | 20 | 5 | 2,740 | 1,210 |

| Fair (3) | 10 | 12 | 1,860 | 800 |

| Poor (2) | 5 | 25 | 990 | 390 |

| Critical (1) | <5 | >25 | <990 | <390 |

The average value of the indicators was converted to an ordinal scale with values ranging from 1 to 5, resulting in 5 health values: critical (1), poor (2), fair (3), good (4), and very good (5). The final values of each indicator were averaged to obtain the RHI rating (McField et al. 2022, 2024); the standard error was then calculated to determine its variation by region, system, and reef site.

Statistical analysis

To identify interactions or factors with a significant effect on the community structure of hard corals, a type II permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) was performed with 1,000 permutations (Anderson and Walsh 2013), considering 3 factors: fleshy macroalgae cover, herbivorous fish biomass, and commercial fish biomass. Prior to the analysis, the coral cover matrix was square-root transformed, and the Bray-Curtis similarity index was calculated. This analysis was performed using the PRIMER statistical package with PERMANOVA V7 (Clarke and Gorley 2015).

RESULTS

Southwestern Gulf of Mexico: coral and fleshy macroalgae cover

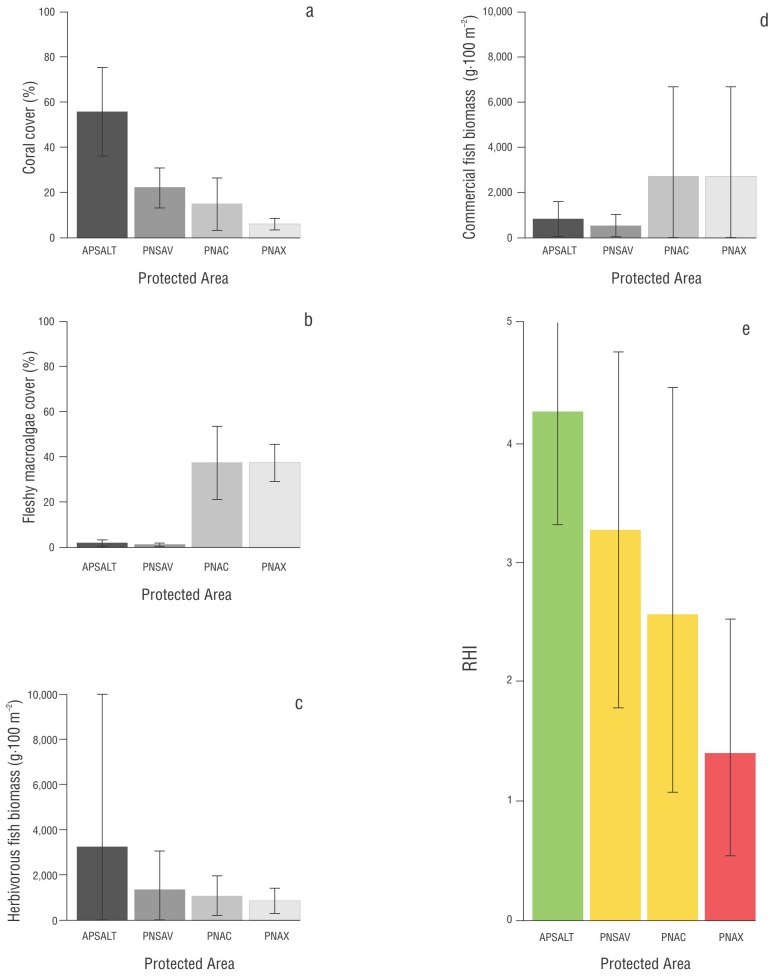

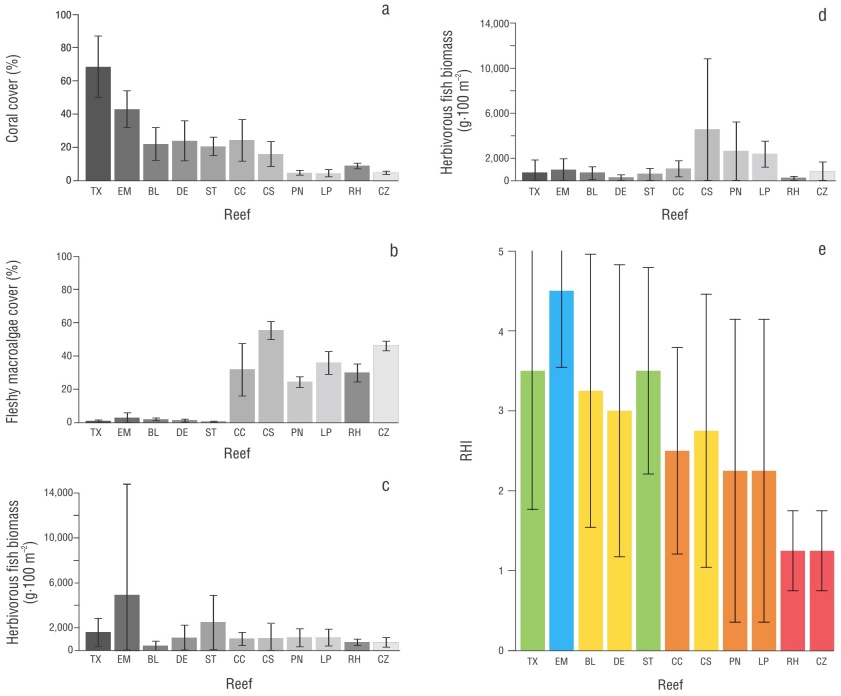

In total, 26 stony coral species were recorded in the SGM, of which Siderastrea siderea, Siderastrea radians, Montastraea cavernosa, Pseudodiploria strigosa, Colpophyllia natans, Porites colonensis, Orbicella annularis, Orbicella faveolata, Porites astreoides, and Acropora cervicornis had the highest cover values. The APSALT had greater coral cover (55.66%) than the PNSAV (22.14%; Fig. 3). The reefs Tuxpan (68.46%) and De Enmedio (23.92%) had the highest cover in each system, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 3).

Table 2 Reef Health Index (RHI) results for each region, system, and reef. The 5 ratings are indicated by the following colors: blue (very good), green (good), yellow (fair), orange (poor), and red (critical). Southwest Gulf of Mexico (SGM); Lobos-Tuxpan Reef System Flora and Fauna Protection Area (APSALT, for its acronym in Spanish); Sistema Arrecifal Veracruzano National Park (PNSAV, for its acronym in Spanish) ; Mexican Caribbean (MC); Arrecifes de Cozumel National Park (PNAC, for its acronym in Spanish); Arrecifes de Xcalak National Park (PNAX, for its acronym in Spanish).

| Region/System/Reef | RHI | Corals (%) | Fleshy macroalgae (%) | Herbivorous fish (g·100 m-2) | Commercial fish (g·100 m-2) |

| SGM | 3.50 | 38.90 | 1.41 | 2,298.28 | 654.62 |

| APSALT | 4.25 | 55.66 | 1.68 | 3,258.95 | 808.59 |

| Tuxpan | 3.50 | 68.46 | 0.61 | 1,601.25 | 672.64 |

| Enmedio | 4.50 | 42.85 | 2.73 | 4,916.64 | 944.54 |

| PNSAV | 3.25 | 22.14 | 1.13 | 1,337.62 | 500.66 |

| Blanca | 3.25 | 22.02 | 1.86 | 383.32 | 666.44 |

| De Enmedio | 3.00 | 23.92 | 1.11 | 1,117.36 | 266.26 |

| Santiaguillo | 3.50 | 20.48 | 0.42 | 2,512.18 | 569.28 |

| CM | 2.50 | 10.49 | 37.16 | 962.00 | 1,908.50 |

| PNAC | 2.75 | 14.96 | 37.13 | 1,073.85 | 2,709.45 |

| Caracolillo | 2.50 | 24.27 | 31.72 | 1,023.94 | 1,043.08 |

| Colombia Somero | 2.75 | 16.00 | 55.35 | 1,074.62 | 4,507.27 |

| Paraíso Norte | 2.25 | 4.60 | 24.33 | 1,123.00 | 2,578.01 |

| PNAX | 1.50 | 6.02 | 37.20 | 851.41 | 1,108.91 |

| La Poza | 2.25 | 4.43 | 35.79 | 1,134.54 | 2,340.58 |

| Río Huach | 1.25 | 8.85 | 29.76 | 721.32 | 196.71 |

| Canal de Zaragoza | 1.25 | 4.78 | 46.03 | 698.37 | 789.45 |

very good, good, fair, poor, critical.

Figure 2 Values obtained for each indicator and reef health index (RHI) score for each system. Average cover of hard corals (a); average cover of fleshy macroalgae (b); average biomass of herbivorous fish (c); average biomass of commercial fish (d); RHI score (e). Lobos-Tuxpan Reef System Flora and Fauna Protection Area (APSALT, for its acronym in Spanish); Sistema Arrecifal Veracruzano National Park (PNSAV, for its acronym in Spanish); Arrecifes de Cozumel National Park (PNAC, for its acronym in Spanish); Arrecifes de Xcalak National Park (PNAX, for its acronym in Spanish).The green, yellow, and red colors indicate the RHI qualitative rating: green (good), yellow (fair), and red (critical). The gray tones represent the reef systems. The error bars correspond to the standard deviation values.

Figure 3 Values obtained for each indicator and RHI score for each reef. Average cover of hard corals (a); average cover of fleshy macroalgae (b); average biomass of herbivorous fish (c); average biomass of commercial fish (d); Reef Health Index (RHI) score (e). Tuxpan (Tx); Enmedio (EM); Blanca (BL); De Enmedio (DE); Santiaguillo (ST); Caracolillo (CC); Colombia Somero (CS); Paraíso Norte (PN); La Poza (LP); Río Huach (RH); Canal de Zaragoza (CZ). The green, yellow, and red colors indicate the qualitative RHI score: green (good), yellow (fair), and red (critical). The gray tones represent the reef systems. The error bars correspond to the standard deviation values.

Fleshy macroalgae cover was higher in the APSALT (1.68%) than in the PNSAV (1.13%; Fig. 2). The highest cover was observed in the Enmedio reef (2.73%) in the APSALT, and Blanca reef (1.86%) in the PNSAV. The lowest cover was observed in the Tuxpan Reef (0.61%) and Santiaguillo Reef (0.42%) for the APSALT and PNSAV, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 3). It should be noted that macroalgae cover did not exceed 3% in all SGM reefs.

Southwestern Gulf of Mexico: herbivorous and commercial fish biomass

In total, 11 herbivorous fish species were recorded in the SGM. The species Scarus guacamaia, Acanthurus chirurgus, Scarus iseri, Scarus vetula, and Sparisoma viride had the highest biomasses, which constituted 91% of the total biomass. The families Acanthuridae and Scaridae had the highest biomass in the APSALT (3,258.95 g·100 m-2; Table 2, Fig. 2). In this system, the Enmedio Reef (4,916.64 g·100 m-2) had the highest values of this indicator, whereas for the PNSAV (1,337.62 g·100 m-2), the Santiaguillo Reef had the highest values (2,512.18 g·100 m-2; Table 2, Fig. 3). It should be noted that the biomass of scarids exceeded that of acanthurids in both reefs.

In the SGM, 19 commercially important fish species were recorded. The species Ocyurus chrysurus, Lutjanus griseus, Epinephelus adscensionis, Cephalopholis cruentata, Mycteroperca bonaci, Lutjanus cyanopterus, Lutjanus analis, Lutjanus synagris, and Mycteroperca phenaxhighest had the highest biomasses, which constituted 90% of the total biomass. The families Lutjanidae and Serranidae had the highest biomasses in the APSALT (808.59 g·100 m-2; Table 2, Fig. 2), where the Enmedio Reef (944.54 g·100 m-2) had the highest values for this indicator. For this reef, the biomass of lujanids was higher than that of serranids. In the case of the PNSAV (500.66 g·100 m-2), the Blanca Reef had the highest values (666.44 g·100 m-2; Table 2, Fig. 3), with higher biomass of serranids than of lujanids

Mexican Caribbean: coral and fleshy macroalgae cover

In the MC, 24 species of hard corals were recorded, of which S. siderea, O. faveolata, P. astreoides, Agaricia tenuifolia, Agaricia agaricites, Porites porites, Porites furcata, and Porites divaricata had the highest cover values. The PNAC showed greater coral cover values (14.96%) compared to the PNAX (6.02%; Fig. 2); the Caracolillo (24.27%) and Río Huach (8.85%) reefs had the highest cover values within these systems, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 3).

Fleshy macroalgae cover was similar in PNAC (37.13%) and PNAX (37.20%; Fig. 2). The highest cover values were recorded in the Colombia Somero Reef (55.35%) and in Canal de Zaragoza (46.03%) for the PNAC and PNAX, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 3). The lowest cover values were observed in the Paraíso Norte (24.33%) and Río Huach (29.76%) reefs for the PNAC and PNAX, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 3).

Mexican Caribbean: biomass of herbivorous and commercial fish

In the MC, 10 herbivorous fish species were recorded. Sparisoma viride, Sparisoma aurofrenatum, Acanthurus coeruleus, Sparisoma chrysopterum, S. iseri, and S. vetula contributed the highest biomasses, which represented 90% of the total biomass. The families Acanthuridae and Scaridae had the highest biomass values in the PNAC (1,073.85 g·100 m-2; Table 2, Fig. 2). At PNAC, Paraíso Norte Reef had the highest biomass value (1,123.00 g·100 m-2); at PNAX (851.41 g·100 m-2), La Poza Reef had the highest values (1,134.54 g·100 m-2; Table 2, Fig. 3). In both reefs, the biomass of scarids exceeded that of acanthurids.

In the MC, 13 commercially important fish species were recorded. Lutjanus griseus, Lutjanus apodus, O. chrysurus, Lutjanus mahogoni, L. synagris, and Lutjanus jocu contributed the highest biomasses, which represented 90% of the total biomass. The families Lutjanidae and Serranidae had the highest biomass values in the PNAC (2,709.45 g·100 m-2; Table 2, Fig. 2). The Colombia Somero Reef in the PNAC had the highest biomass (4,507.27 g·100 m-2); in the PNAX (1,108.91 g·100 m-2), La Poza Reef had the highest values (2,340.58 g·100 m-2; Table 2, Fig. 3). The biomass of lujanids exceeded that of serranids in both reefs.

Reef health index (RHI)

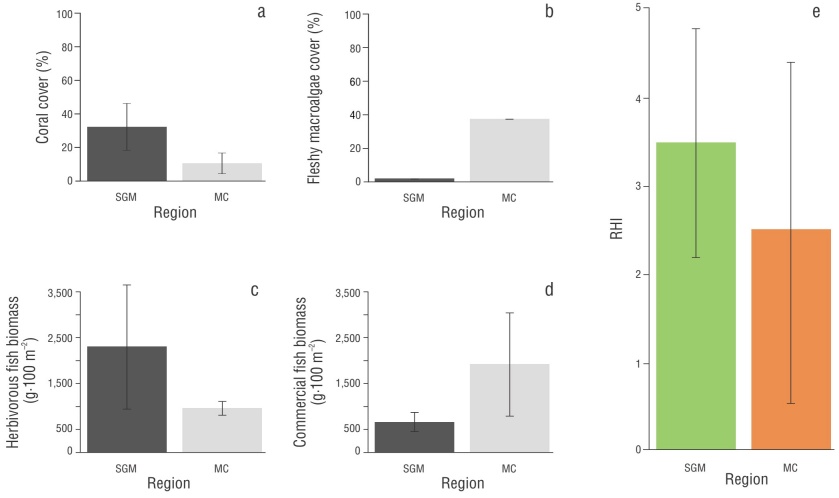

Overall, the SGM obtained a health rating of good (3.50). The APSALT had a RHI rating of 4.25, which classified its condition as good, as observed for the Tuxpan Reef (3.50). The Enmedio Reef was the only one with a health status classified as very good (4.50; Table 2). The PNSAV, with an RHI rating of 3.25, was classified as having fair health. In this system, only Santiaguillo Reef (3.50) showed a health status classified as good, whereas the statuses of the Blanca (3.25) and De Enmedio reefs (3.00) were classified as fair (Table 2).

In contrast, the MC system had a health status classified as poor (2.50), lower than the SGM system. The PNAC had an RHI score of 2.75, a condition classified as fair. In this system, the conditions of the Caracolillo (2.50) and Paraíso Norte (2.25) reefs were classified as poor, whereas the condition of Colombia Somero (2.75) was classified as fair. The PNAX showed a critical health condition (1.50). In addition, in this system, the Río Huach (1.25) and Canal de Zaragoza (1.25) reefs had conditions classified as critical. On the other hand, La Poza showed a condition classified as poor (2.25; Table 2).

Regarding RHI indicators, the value of coral cover for the SGM was good (38.90%). In this context, the very good cover values of the APSALT and Tuxpan reefs were notable (55.66% and 68.46%, respectively). In the MC, cover was fair (10.49%; Fig. 4); however, in this region, Caracolillo Reef was distinguished by a cover value classified as good (24.27%). It is worth noting that the cover value for PNAX (6.02%) was classified as critical, as were the values for La Poza (4.43%) and Canal de Zaragoza (4.78%) within this system. For all SGM reefs, macroalgae cover values were very good and did not exceed 3% in all cases. Conversely, for MC reefs, the macroalgae cover values were critical, with values greater than 24% in all cases. Particularly in this region, on the Colombia Somero Reef, macroalgae cover exceeded 50% (Table 2), which indicated a reef dominated by fleshy macroalgae.

Figure 4 Values obtained for each indicator and RHI score for each region. Average cover of hard corals (a); average cover of fleshy macroalgae (b); average biomass of herbivorous fish (c); average biomass of commercial fish (d); Reef Health Index (RHI) score (e). Southwestern Gulf of Mexico (SGM); Mexican Caribbean (MC). The green and orange colors indicate the qualitative RHI score: green (good), orange (poor). The gray tones represent the regions. The error bars correspond to the standard deviation values.

For the SGM, the biomass of herbivorous fish was fair (2,298.28 g·100 m-2), and only the Blanca Reef showed a critical state (383.32 g·100 m-2). For the MC, the biomass of herbivorous fish was critical (962 g·100 m-2), since all reefs had poor biomass values, except for Río Huach (721.32 g·100 m-2) and Canal de Zaragoza (698.37 g·100 m-2), which had critical biomass values (Table 2).

For the MC, the value of commercial fish biomass was very good (1,908.50 g·100 m-2), with the Colombia Somero, Paraíso Norte, and La Poza reefs standing out with very good values. Río Huach was the only reef with critical biomass values (196.71 g·100 m-2). On the other hand, the SGM had a rating considered poor (654.62 g·100 m-2), with the De Enmedio Reef being the only one with a critical biomass value (266.26 g·100 m-2).

The type II PERMANOVA showed that only the fleshy macroalgae cover factor was significantly related to coral community structure (P < 0.05, P = 0.001; Table 3), indicating that areas with low fleshy macroalgae cover (RHI = good and very good) differ significantly from those with high macroalgae cover (RHI = poor and critical) in terms of coral community structure. Finally, the interactions between the 3 factors (fleshy macroalgae cover, herbivorous fish biomass, and commercial fish biomass) were not significant (P > 0.05).

Table 3 Reef community structure. Result summary of the 3-factor Type II PERMANOVA.

| Factor | Pseudo-F | P(perm) |

| Fleshy macroalgae cover | 7.1975 | 0.001 |

| Herbivorous fish biomass | 1.0246 | 0.455 |

| Commercial fish biomass | 1.3092 | 0.185 |

*Results that showed a significant relationship (P < 0.05) are indicated in bold.

DISCUSSION

The health status of SGM reefs, assessed using the RHI, showed an average coral cover of 38.90% (Table 2). This indicator could reflect the interaction of processes that have occurred for approximately 220 million years (Tunnell et al. 2007), along with anthropogenic alterations that have affected the resilience and adaptive capacity of corals in this region. The importance and coral development of these reefs has been highlighted in previous studies (Horta-Puga 2003, Escobar-Vásquez and Chávez 2012), suggesting that, despite environmental pressures, these ecosystems have maintained a significant size and cover (Gil-Agudelo et al. 2020).

The SGM reefs are located on a terrigenous continental shelf (Morelock and Koenig 1967, Tunnell et al. 2007) and are exposed to turbid conditions (Tunnell 1988, 1992) due to their proximity to the coast (Horta-Puga et al. 2015). This turbidity results from the discharge of siliciclastic sediments transported by numerous hydrological basins during the rainy season (Carriquiry and Horta-Puga 2010, Mateos-Jasso et al. 2012, CONABIO 2013) and the resuspension of sediments generated by cold fronts (Avendaño-Álvarez et al. 2017). Despite these adverse conditions, SGM reefs have demonstrated a remarkable capacity for adaptation across geological scales (Roche et al. 2018, Dee et al. 2019).

In Singapore, for example, reefs that persist in disturbed, urbanized environments and chronic turbidity have been observed to transition to more tolerant species to withstand current and future disturbances (Januchowski-Hartley et al. 2020).

Furthermore, coral reefs in environments with natural turbidity tend to be more resilient than those with anthropogenic turbidity because the latter have only had short periods to acclimate and adapt (Roche et al. 2018). For example, in the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, reefs such as Middle Reef have been able to survive and maintain high growth rates over the past 9,000 years, despite experiencing high terrigenous sedimentation. The authors suggest that this rapid reef growth is linked to post-death coral skeleton preservation, favored by high levels of terrigenous sediment. This terrigenous sediment tends to coat the skeletons, protecting them from bioerosion and wave action for longer, keeping them intact and, therefore, converting them into stable substrates for new corals to establish. Over time, this process has contributed to reef growth despite adverse turbidity conditions (Perry et al. 2012).

However, although some reef systems, such as those in the SGM, can persist in high turbidity environments, it is important to understand their tolerance limits to sedimentation (Browne et al. 2012). This is especially relevant given that sediments in these reefs come from both natural sources and anthropogenic activities (Tuttle and Donahue 2022).

The PNSAV is located opposite the city of Veracruz, one of the oldest cities in the Americas, founded in 1519 (Melgarejo-Vivanco 1960). Since then, these reefs have been exploited to extract coral to use in construction (Heilprin 1890, Tunnell et al. 2007, Gil-Agudelo et al. 2020) and have been exposed to the impact of port activities (Horta-Puga and Tello-Musi 2009, Horta-Puga et al. 2015, Argüelles et al. 2019). These conditions have subjected the corals to a continuous state of stress for approximately 500 years.

Similarly, APSALT reefs, off the cities of Tuxpan and Tamiahua, have been subjected to pressure since the creation of the port of Tuxpan in 1580 and have been affected by port activities and fuel spills (Ortiz-Lozano et al. 2013, Lozano-Nathal and Ponce-Jiménez 2018). Thus, the natural events that characterize this area, along with the impacts endured by the APSALT and PNSAV reef systems progressively and throughout history, could be favoring the adaptive potential of these reef systems.

The upwelling of oceanic water from the Campeche cyclonic gyre is another natural factor that could be contributing to the good health of SGM reefs (Salas-Pérez et al. 2012, Guerrero et al. 2020); this upwelling limits coral bleaching by bringing in cool waters (<22 °C) and favors coral development with the contribution of nitrogen used by zooxanthellae (Carrasco 2022, Salas-Monreal et al. 2022).

In addition, natural temperature variability in the SGM, where waters cool in the winter (Escobar-Vásquez and Chávez 2012), could increase reef resilience, as reef areas with greater water temperature variability have been shown to be more resistant to thermal stress and bleaching (Safaie et al. 2018, Lachs et al. 2023). Furthermore, reefs in the Gulf of Mexico have experienced thermal stress since 1878 (Kuffner et al. 2015), and the siliciclastic nature of the gulf may make corals more resilient than those found in carbonate environments (Dee et al. 2019). These factors combined could explain the high resistance and resilience of the reefs in the region, especially in species such as C. natans, M. cavernosa, and P. strigosa, which tolerate high sedimentation rates (Horta-Puga et al. 2015) and, in fact, had some of the highest cover values in the region.

In the Yucatán Peninsula, MC reefs developed in oligotrophic waters on a carbonate platform, with little influence of fluvial currents due to the karst nature of the region (Weidie 1985, Merino et al. 1990, Merino 1997, Tunnell et al. 2007). The high permeability of the soil enables water to infiltrate into aquifers, where soils act as natural filters for contaminants (Carballo-Para 2016, Estrada-Medina et al. 2019).

Historically, the region has not shown high sedimentation rates (Horta-Puga et al. 2019). However, in recent decades, there has been an increase in nutrients and sediments associated with human activities (Arias-González et al. 2017, Rogers and Ramos-Scharrón 2022), and, recently, the waters have come to be considered non-oligotrophic (Velázquez-Ochoa and Enríquez 2023). Thus, it is likely that, due to the lack of natural sedimentation throughout its history, the hard coral species of the MC have not had sufficient time to adapt to the effects of anthropogenic sedimentation (Roche et al. 2018).

The state of Quintana Roo is still young (founded in 1974; State Congress 2001); however, coastal development rates in the MC over the past 14 years have been very high (Arias-González et al. 2017), increasing from 88,000 inhabitants in 1975 to 1.5 million in 2015 (Suchley and Alvarez-Filip 2018). This could be associated with a more intense and abrupt impact on the reefs of the MC compared to those of the SGM; this impact could have negatively affected the adaptive capacity of coral species (Roche et al. 2018) and the resilience of these ecosystems (Sandin et al. 2008, Graham et al. 2013, Anthony et al. 2015).

In MC reefs, an accelerated phase shift has been documented, driven by eutrophication and sedimentation as a result of inadequate wastewater treatment (Martínez-Rendis et al. 2015, Suchley et al. 2016, Arias-González et al. 2017, Rioja-Nieto and Álvarez-Filip 2019, Randazzo-Eisemann et al. 2021). These impacts are closely linked to coastal development (Arias-González et al. 2017, Suchley and Álvarez-Filip 2018, Rioja-Nieto and Álvarez-Filip 2019).

The data generated confirmed that the community structure of hard corals is determined by the presence of fleshy macroalgae (Table 3). Although macroalgae are primary producers and a fundamental part of food chains (Pereira 2021), high covers can negatively affect reefs by competing with corals for space, inhibiting larval settlement and hindering their recovery (Díaz-Pulido et al. 2010). This highlights the importance of considering this indicator in reef health assessments in the region.

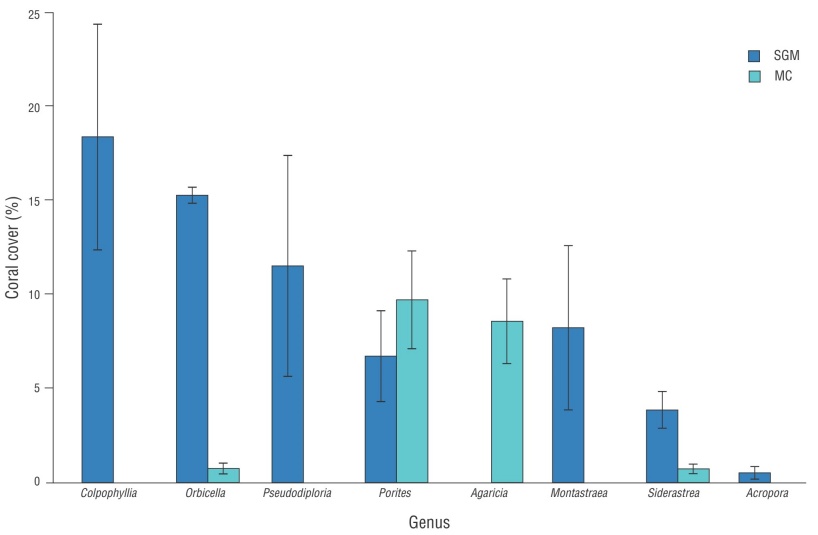

This could be associated with the shift in reef-building species in the MC, from dominant genera, such as Orbicella, Montastraea, and Acropora, to opportunistic and more tolerant genera, such as Porites and Agaricia (Fig. 5), which also contribute very little to calcium carbonate accumulation and reef structural complexity. Furthermore, this trend has consistently been observed across other Caribbean reefs (Barranco et al. 2016, Caballero-Aragón et al. 2020b, Dahlgren et al. 2020, Lima et al. 2022, McField et al. 2022, CCMI 2023, Eagleson et al. 2023).

Figure 5 Average cover for the 8 genera of hard coral with the highest cover in the southwestern Gulf of Mexico (SGM) and the Mexican Caribbean (MC). Error bars correspond to standard deviations.

These results are concerning because it is important not only to conserve high coral cover but also to maintain cover of reef-building corals (e.g., Acropora spp., Orbicella spp.; Alvarez-Filip et al. 2013, González-Barrios 2019, Guendulain-García et al. 2024). The loss of structural complexity affects the three-dimensional structure of reefs and impacts their function as coastal protectors, as they lose the capacity to reduce wave energy (Carlot et al. 2023). This increases the risk of coastal erosion and affects nearby ecosystems, such as mangroves and seagrass beds (Zepeda-Centeno et al. 2018).

Low cover values of fleshy macroalgae (1.41%) indicated that the status for this indicator in the SGM was very good (Table 2), which positively influenced the RHI score for the region (3.50). This value contrasts with that of the MC, where the status for this indicator was critical (Table 2). In the PNSAV, the benthic community is dominated by turf algae, whereas fleshy macroalgae have a lower presence (Horta-Puga et al. 2020). This suggests that low cover values of fleshy macroalgae in SGM reefs do not necessarily imply high herbivore biomasses, but rather a possible association with the dominance of turf algae, as has been observed in this region (Dee et al. 2019).

According to Horta-Puga et al. (2020), it is not possible to establish that the reefs of the PNSAV are in a stable state as in the MC, but rather in an unstable or intermediate state. This is because a stable state is characterized by changes in key elements of the system that result in a dramatic and lasting impact on species composition and ecosystem functioning (Simenstad et al. 1978), whereas an unstable or intermediate state is characterized by high spatial and temporal variability of the key elements, and not necessarily a dominance of any of them (Bellwood and Fulton 2008, Goatley et al. 2016). In coral reefs, there are 2 stable states, one dominated by corals and the other dominated by fleshy macroalgae (Mumby and Steneck 2008, Mumby 2009).

A shift from a steady state of a coral reef to a stable state dominated by fleshy macroalgae has already been reported in the MC (Randazzo-Eisemann et al. 2021). Likewise, such events have been reported in other ecosystems, such as the shift from a steady state of macroalgae forests to rocky, sterile, and low-biodiversity marine environments, as a consequence of high urchin abundances (Ling et al. 2015, McPherson et al. 2021, Eger et al. 2024). Nevertheless, unstable or intermediate states have also been recorded in coral reefs, where other benthic organisms, in addition to fleshy macroalgae, become dominant (e.g., sponges, gorgonians, turf algae; Norström et al. 2009, Graham et al. 2014) in response to constant anthropogenic disturbances (Norström et al. 2009). These intermediate states tend to become stable when large-scale coral mortality occurs, creating positive feedback loops, which amplify and reinforce the process, preventing the reef from recovering to its original state (Norström et al. 2009, Van de Leemput et al. 2016).

Therefore, PNSAV reefs could likely be heading towards an unstable or intermediate state dominated by turf algae (Horta-Puga et al. 2020). This could also be the case for APSALT reefs, as an increase in turf algae cover has also been reported in the area (Escobar-Vasques and Chávez 2012, Cancino-Guzmán 2018, González-Gándara and Salas-Pérez 2019), which would consequently have implications for the coral cover of the reefs.

Although not reflected in our reported results, turf algae had higher cover values than fleshy macroalgae during the SGM frame analysis (SGM: 17.81%; APSALT: 14.38%; PNSAV: 20.11%; Enmedio: 14.90%; Tuxpan: 13.85%; Blanca: 27.70%; De Enmedio: 19.50%; Santiaguillo: 13.17%). This could be encouraging for the reefs of this region, since coral recruits have been shown to establish and grow, albeit slowly, in dense mats of turf algae (Birrell et al. 2005, 2008). Conversely, this process of coral recruit settlement does not occur when fleshy macroalgae dominate the seafloor.

Thus, if recruitment continues, corals could surpass turf algae (Birrell et al. 2005, 2008; Swierts and Vermeij 2016). However, it is important to note that turf algae can also be displaced by fleshy macroalgae (Fung et al. 2011), where herbivory by fish and sea urchins would play an important role in the competition between these 2 algal groups (Arias-González et al. 2017).

These results suggest that special attention should be paid to the cover of both algal groups in the SGM and that they should be monitored because the current state could take 2 paths: (1) an ideal state, with reefs dominated by corals, or (2) a less desirable scenario, with a dominance of turf algae, which would imply a phase shift, similar to that experienced in the MC with fleshy macroalgae. This is especially relevant considering that some authors, such as Harris et al. (2015), have pointed out that an increase in the abundance of turf algae is expected in the future, given that they can survive in conditions unfavorable to corals.

The better health status of the APSALT (good) compared to the PNSAV (fair) (Table 2) coincides with the idea that the reefs in northern Veracruz (APSALT) are in better condition than those in the south (PNSAV; Chávez et al. 2007). Nonetheless, attention should be directed toward fish communities, especially in PNSAV and the Tuxpan reef of APSALT, whose ratings ranged from critical to fair (Table 2).

This could reflect the pressure of artisanal fishing on the coast of Veracruz (Ortiz-Lozano et al. 2019). Another factor to consider is that only reefs from the southern group were sampled in both systems, which could have influenced the results, as the conservation status of reefs of the southern group of the PNSAV has been reported to be better than that of the northern group (Chávez et al. 2007).

Regarding the scores obtained, the work by Simoes et al. (2020) classifies the health status of the SGM, APSALT, and PNSAV as fair, using different indicators and criteria than those used for the RHI. Nevertheless, we can compare these results with those obtained in the present study (Table 2), where the scores were good for the SGM and APSALT, and fair for the PNSAV.

On the other hand, Pérez-España et al. (2021) used the RHI to assess the health status of 15 reefs in the PNSAV. Although the individual scores for each indicator differed from those obtained in this study, probably due to an adjustment made by these authors to the RHI criteria based on recent studies in the PNSAV (last 10 years), the average score obtained (fair) coincides with that of this study. In the present study, we did not use the adjusted criteria of Pérez-España et al. (2021) because we selected the RHI criteria established by the HRI for a standardized assessment. It is important to note that there are no previous studies for the APSALT based on the RHI, which limits the comparison with the results presented here.

The PNAC showed the best health status within the MC (fair), which coincides with that reported by McField et al. (2022), where the PNAC was identified as one of the best conserved sites in the MC and MAR, with 35% of its reefs under full protection, higher than anywhere else in the region. Previous studies in the PNAC that use the RHI also indicate that the biomasses of herbivorous and commercial fish are in good health (Pérez-Cervantes et al. 2017); these values are the highest in the MAR (McField et al. 2022).

The improved health status of the PNAC could be the result of the conservation strategy implemented by the Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP) in 2019, which included the temporary suspension of tourist activities in certain areas of the National Park to promote recovery from the impact of the white syndrome (CONANP 2019). Furthermore, the circulation of currents in the area could mitigate the effects of sedimentation and continental debris (Contreras-Silva et al. 2020).

The corals of the PNAC are considered among the most resilient in the MC, with high coral cover (Barranco et al. 2016, Contreras-Silva et al. 2020), where the leeward reefs show greater development because they are protected from winds and storms (Fenner 1988). In addition, the critical state for the PNAX is consistent with that observed by the HRI (2012) and, more recently, by Díaz-Pérez et al. (2016), who reported highly deteriorated and critical conditions for the PNAX.

This is likely due to local anthropogenic pressure, derived from tourism and agriculture, and inadequate reef management in the southern part of the MC (Contreras-Silva et al. 2020). Therefore, our results reflect the intensity and pressure exerted by the rapid coastal development of the last 14 years in the MC, where PNAC reefs still present the best conditions.

The SGM and PNAC reefs are the most resilient in the MC (Contreras-Silva et al. 2020) and could act as resilience hotspots, that is, areas where corals have demonstrated a greater capacity to resist and recover from environmental and anthropogenic disturbances, such as climate change and human activity (Nyström et al. 2008; McClanahan et al. 2012; McLeod et al. 2019, 2021). These areas are characterized by their ecological stability and their potential to serve as natural sanctuary areas, making them key sites for reef conservation in the region (McClanahan et al. 2014, McLeod et al. 2019, Bang et al. 2021, Moritsch and Foley 2023). However, the speed of climate change is likely to exceed the speed at which corals can adapt (Frieler et al. 2013).

Therefore, further studies are needed for SGM reefs to help expand on and understand the ecological and environmental processes that make the persistence of these reefs possible in an environment of high sedimentation and turbidity, as suggested by Salas-Pérez and Granados-Barba (2008) for the PNSAV. In addition, their tolerance thresholds need to be determined because the future trend is towards greater deposition of anthropogenic sediments and thermal stress, which will also be catastrophic for the less resilient reefs of the MC.

Finally, the biomass results should be interpreted with caution because samplings were conducted during different periods in the 2 regions, and fish abundance may fluctuate seasonally. In addition, it is important to consider that commercial fish species tend to be highly mobile, traveling long distances, so sampling for this indicator should be conducted more frequently to obtain results representative of the current status of this indicator (McField and Kramer 2007).

The RHI has proven to be key to understanding reef conditions at the regional level, such as the MAR. However, to gain more detailed knowledge of other regions, it is essential to consider other local indicators, such as water quality, as suggested by Horta-Puga and Tello Musi (2009) and Simoes et al. (2020) for the Gulf of Mexico, because environmental conditions, such as water quality, have been observed to influence the cover of algal groups (Horta-Puga et al. 2020).

It is essential to implement an ongoing reef health assessment program for reefs in the SGM and MC. Periodic assessments facilitate comparing trends over time to provide a true measure of reef health. These assessments, along with resilience-based management strategies (McLeod et al. 2019, Obura et al. 2019, Vardi 2021, Moritsch and Foley 2023), will be key to reef management and conservation in the Mexican Atlantic.

CONCLUSIONS

The results obtained using the RHI led to the following key conclusions: (a) reefs in the SGM had greater coral cover than those in the MC; (b) a phase shift is already evident in the MC, whereas in the SGM, the low cover of fleshy macroalgae would indicate that it is still in an intermediate stage; (c) the high cover of fleshy macroalgae in the MC negatively affected its health status; (d) the lower biomasses of herbivorous fish reported in the MC could corroborate their relationship with the high macroalgae cover observed; (e) the higher biomasses of commercial fish recorded in the MC, particularly in the PNAC, suggest the effectiveness and importance of conservation strategies; and finally, (f) reefs in the SGM had better health conditions than those in the MC, which could be related to the natural and anthropogenic history of both regions.

texto en

texto en