Introduction

The process of receiving a kidney transplant (KT) is complex and requires the participation of a multidisciplinary team working together with the patients and their families. Social work (SW) plays a key role in assessing and supporting patients in the socioeconomic aspects that affect their entire health-care process. SW takes action across three stages of the process: before, during, and after the transplant, with the objectives of assessment, support, and follow-up1.

In some health-care systems, SW has developed specific intervention programs to work along with the patients and their families, both regarding organ donation and the entire transplant process2-6. In Mexico, general transplant protocols have been implemented in the public sector, including SW tasks associated with patient assessment and administrative support7,8. However, specific social intervention programs with this population have not been reported and evaluated to this date.

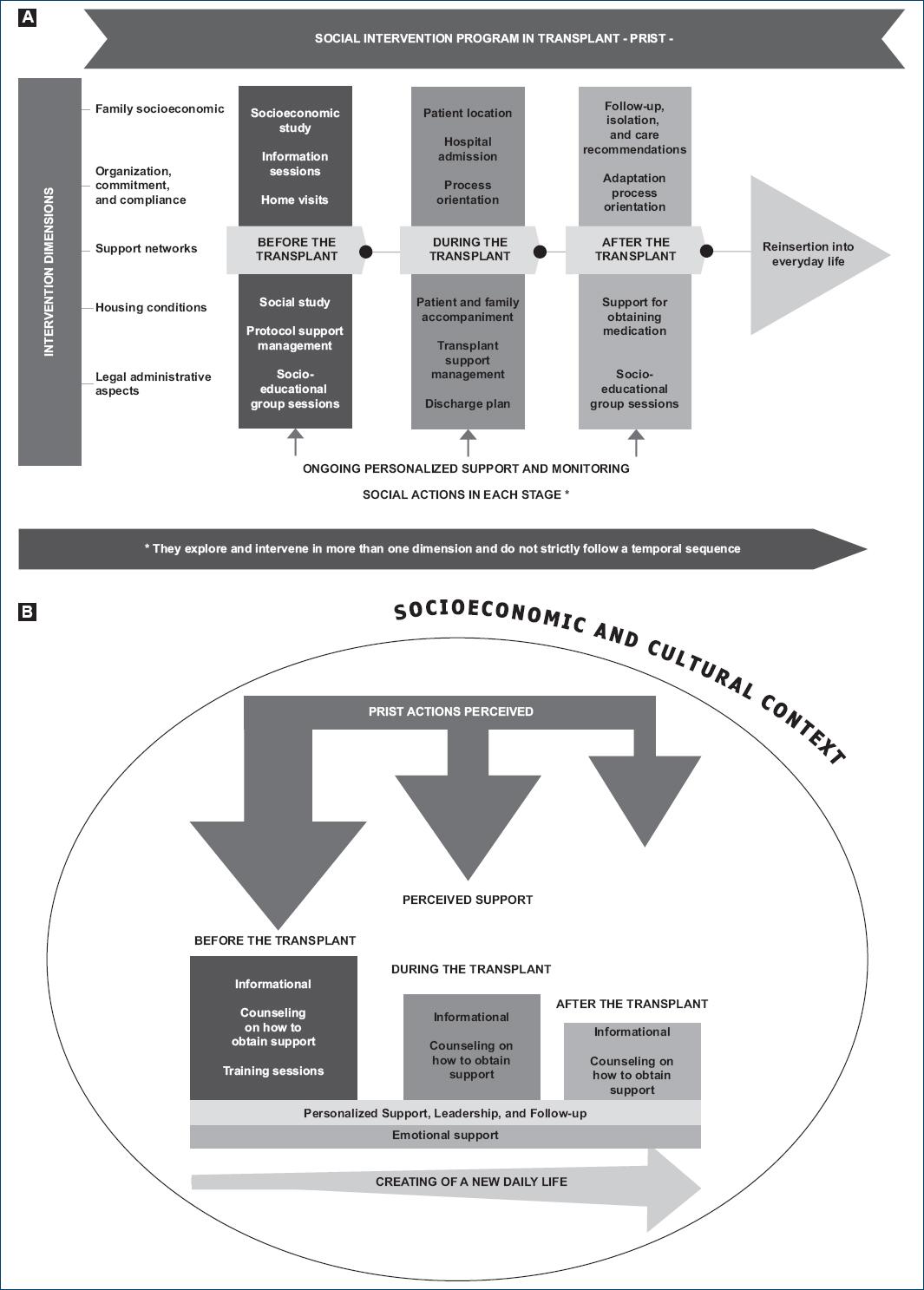

SW practices are based on theoretical and methodological models rooted in psychological, social, and administrative perspectives9,10 (Fig. 1). These models can be applied to various levels of care related to the user: individual, group, and community11, guiding the functions of social diagnosis and intervention in settings such as the hospital one12. Starting in 2012, Hospital General de México "Dr. Eduardo Liceaga" (HGM) initiated the implementation of the Social Intervention Program in Transplant (PRIST, by its Spanish acronym) by the Department of Social Work and Public Relations built on SW intervention models, the needs of the hospital population, and the experiences of social workers.

PRIST is developed with the purpose of assessing, educating, and supporting the patients and their families across the different stages of the transplant process under a person- and family-focused health-care approach, including the role their families have played in their lives, and the support provided by these families to facilitate a health recovery13. The program includes specific and cross-cutting actions in each one of the dimensions: socioeconomic family conditions, organization, commitment, and compliance, support networks, housing conditions, and administrative and legal aspects across the entire intervention process. In the pre-transplant stage, actions involve assessment, intervention planning, and guidance to prepare the patients and their families for transplantation. During the transplant stage, the SW provides guidance and accompaniment during surgery and post-operative care, manages support, and assists in hospital administrative procedures. After the transplant, the SW guides the process of adaptation and care plan for the isolation and gradual reinsertion into everyday life (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 A: Social Intervention Program in Transplant -PRIST-. B: Representation of how PRIST works in the actual social work practice.

Given that PRIST has been implemented in the HGM for over 10 years and that various studies have shown that KT recipients have psychosocial needs of emotional support, acceptance, guidance, and equitable healthcare, most of which remain unmet due to the lack of interventions, or methodology limitations14, the objective of this study was to qualitatively evaluate this program in KT recipients treated at the organ donation and transplantation unit by identifying and describing the support perceived by them during their health-care process in the SW setting.

Materials and methods

This was a qualitative and descriptive study that used theoretical assumptions from the systems theory, which recognizes a system as an entity that interacts with others and mutually feeds back to maintain its functioning. In the social context, individuals are part of social systems and subsystems that interrelate and can affect the responses that lead to social behaviors15.

Semi-structured interviews were held, following an interview guide (Table 1) to evaluate PRIST across different transplantation stages. The interview guide was developed using a transdisciplinary approach involving SW, medicine, and medical anthropology. The interviews were conducted over 7 months (from 2022 through 2023). Adult KT recipients at HGM from 2015 through 2022 were invited to participate and selected through convenience sampling16. Interviews were conducted at a private location inside the hospital, with a mean duration of one and a half hours. Furthermore, the interviews were audio-recorded for transcription and analysis. The number of interviews was determined based on the criterion of information saturation and richness16, which was applied to the interviews of the target participants (those who received a KT from 2015 through 2022 and were directly assisted by social workers).

Table 1 Interview guide for PRIST assessment

| Instructions | The following topics are a guide for conducting semi-structured interviews with kidney transplant recipients. The aim is to encourage recipients to express freely on the proposed topics, allowing for the addition of information, or further exploration based on each interviewees experiences and personal history. |

| Notes for the interviewer: | |

| It is not necessary to ask all the questions. Select from the prompts if the information has not been addressed during the interview. | |

| The order of the interview can be adjusted based on topics raised by the participant. You may revisit a previous topic, or move on to a different one to go on with the conversation. | |

| Inform the interviewee that we want to learn from him/her and know more about his/her experiences. There are no right or wrong answers. | |

| Clearly explain the purpose of the study to the participant and obtain his/her consent before starting the interview. | |

| Take notes after the interview on the interview setting (e.g., interruptions, other people present, disturbances, any issues that may have arisen). Transcribe the audio recording as soon as possible. | |

| Sociodemographic Data | Interview date |

| Name | |

| Age | |

| Place of birth | |

| Place of residence | |

| Education level | |

| Marital status | |

| Occupation | |

| Medical diagnosis | |

| Languages | |

| Eth-nic group | |

| Phone number | |

| Themes | History with the illness and transplant |

| Journey through health-care services and experiences in each service | |

| Relationship with health-care professionals | |

| Understanding of the illness | |

| Actions and decision-making regarding diagnosis and medical treatment | |

| Limitations associated with the illness and the transplant | |

| Description of family structure and dynamics | |

| Social support networks, and description of perceived support | |

| Religion, beliefs, and customs | |

| Family, social, occupational, economic, and emotional effects of illness and transplant | |

| Everyday life before and after the transplant | |

| Future plans |

A thematic analysis followed, involving the blind coding of information by the researchers, followed by the creation of categories and themes to organize and prioritize information to guide the interpretative process, using the ATLAS.ti 23 software17. The results were triangulated to verify concordance with the categories and enrich the interpretation.

Ethical disclosures

This work is part of a larger research project approved by HGM research and ethics committees with registration no. DI/22/310/03/51. The overall objective of the project is to explore resilience, coping, and social support in KT recipients. Patients voluntarily agreed to participate in the research after reading and signing the informed consent forms. The corresponding biosecurity measures were observed.

Results

A total of 13 individuals participated, with a mean age of 36 years, including six women (46.1%), and a mean of 13 years of education. Five (38.4%) received transplants from living donors, while two received re-transplants (Table 2). A total of six themes associated with perceived support during the three intervention phases were identified: 1. Informational support; 2. Guidance and institutional management; 3. Social evaluation and educational intervention; 4. Monitoring of the preparation and adaptation process; 5. Emotional support; and 6. SW leadership based on empathy.

Table 2 Sociodemographic data of participants

| Patient no. | Age | Gender | Civil status | Education | Residence | Occupation | Ethnic group | Type of transplant | Transplant time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 27 | Man | Single | High school | Estado de México | Administrative assistant worker | Non-indigenous | DDKT | 2 years |

| 2 | 40 | Man | Single | Primary | Estado de México | Elementary activities and support staff | Náhuatl | DDKT | 7 years |

| 3 | 52 | Woman | Single | University | Mexico City | Professional- technician | Non-indigenous | LDKT | 6 years |

| 4 | 24 | Man | Single | Postgraduate | Estado de México | Student | Non-indigenous | LDKT | 2 years |

| 5 | 39 | Man | Married | High school | Mexico City | Merchant, sales employee, and sales agent | Non-indigenous | DDKT | 6 years |

| 6 | 34 | Woman | Single | University | Estado de México | Professional- technician | Non-indigenous | DDKT/DDKT | 4 years/ 1 year |

| 7 | 39 | Woman | Cohabitation | High school | Mexico City | Stylist | Non-indigenous | LDKT | 2 years |

| 8 | 29 | Woman | Single | High school | Mexico City | Elementary activities and support staff | Non-indigenous | LDKT | 3 years |

| 9 | 29 | Man | Single | High school | Estado de México | Merchant, sales employee, and sales agent | Non-indigenous | LDKT/DDKT | 6 years/ 3 years |

| 10 | 31 | Man | Single | University | Estado de México | Civil worker, CEO, and manager | Non-indigenous | LDKT | 5 years |

| 11 | 49 | Man | Cohabitation | Primary | Mexico City | Agricultural, livestock, forestry, hunting, and fishing worker | Náhuatl | DDKT | 7 years |

| 12 | 32 | Woman | Single | High school | Estado de México | Housewife | Non-indigenous | DDKT | 7 years |

| 13 | 44 | Woman | Single | High school | Mexico City | Student/Seamstress | Non-indigenous | DDKT | 7 years |

DDKT: Deceased donor kidney transplant; LDKT: Living donor kidney transplant.

Informational support: This support is highly valued by the patients and their families to make informed decisions on the transplant and the implications associated with each stage of the process. Its importance is emphasized due to the lack of knowledge on the entire preparation and transplant process (Table 3).

Guidance and institutional management: Guidance and management, particularly associated with material support, are essential for patients, facilitating access to aid organisations and ongoing transplant ation process (Table 3).

Social evaluation and educational intervention: The assessment of socioeconomic and housing conditions favors preparation for transplantation and access to treatment. Individual and group sessions are positive to receive informational and emotional support (Table 3).

Monitoring of the preparation and adaptation process: Direct, clear, and respectful interaction in monitoring the process activates the patients commitment and responsibility toward the entire process and its outcomes (Table 3).

Emotional support: Some participants acknowledge that SW provides emotional support with which to motivate and cope with the entire process. However, this support is perceived in contrasting ways. One patient reports that SW encouraged him to promote transplantation and its benefits, while another participant recognizes the lack of emotional support from the healthcare team involved (Table 3).

SW leadership based on empathy: Participants recognize SW as a constant presence that understands their particular situation and suggests, and motivates continuity during the entire process, despite obstacles (Table 3).

Table 3 Participants narratives on perceived support

| Stage/Theme | Before the transplant | During the transplant | After the transplant |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Informational support | Certainly, it was tough at the beginning, but with the help and guidance from the hospital, all those doubts started to clear up. So, we followed what they recommended for us here, and you know, we said, "Lets go" (Patient #1). | Sometimes I would say, "Ill ask the social worker all questions I may have because the doctors were driving me nuts due to how theyd talk to me, or because theyd explain things to me so quickly that I couldnt understand" (Patient #12). | First, I went to postoperative care in the Morelos neighborhood, but when they told us that there would be a home visit, and I didnt qualify, they changed my address to San Antonio Abad, and thats where I received the home visit. [The SW] asked, "What medicines were you on?" (Patient #5). |

| 2. Guidance and institutional management | - How did you find out about this place? - Because they gave us information here, and then my dad went searching, and they were going to support us there too (Patient #2). | We also had to write letters to aid organisations, and they also helped us, as well as the hospital (Patient #8). | At the beginning of the surgery, it was the aid organisation, but after the transplant and everything, they helped with the medicines, and Ive been in contact with them ever since (Patient #4). |

| 3. Social evaluation and educational intervention | I wasnt at home because at that time, the social worker came to my house, and said that my home didnt qualify for home care, so a family uncle of my mom had several rooms available, and the social worker said I could stay there (Patient #1). | In social work, they obviously talked to us a lot, and all that information clears up a lot of things, many doubts (Patient #1). | During the pandemic, I lost my job and, as a result, I was selling a everything. So, I approached social work to update the socioeconomic assessment and request assistance with free healthcare coverage by the Federal Goverment. For me, it was really helpful because I had no money at all (Patient #13). |

| 4. Monitoring of the preparation and adaptation process | Thats when they referred me to social work.. we talked about my situation, which was quite unique. We had nothing, no job, no papers, nothing. So, I had to start the process of getting my immigration documents ready to be able to receive treatment legally. They also explained in that conversation that the transplant had a significant legal component. So, thats where I rushed to get my documents, or try to obtain Mexican documents (Patient #10). | - When you were nearing your transplant, did you make any appointments with the social worker? - Yes, I did; but very few of them. It was when we were dealing with the paperwork for the transplant. But yes, I mean, Ive been grateful to this hospital because they have been very supportive (Patient #11). | Thank God, Im doing well, Im at 100%. We continue coming to regular appointments because its part of the entire transplant process. We continue with treatments, medicines, and remain diligent. (Patient #4). |

| 5. Emotional support | Yes, I received support from social work since the first transplant. At that time, there was a social worker there, and for me personally, it was an essential part of the transplant process because she really meant a lot to me (Patient #6). | Social work motivated me. Its a path where I ended up. It gave me the opportunity to join a TV station, so a lot of people heard my story (Patient #5). | After the transplant, though, Im not saying youre going to have a happy life just because you had a transplant, no, because there are other factors that should be considered. But if youve already received the transplant, its like motivation to get rid of all those things that used to bring you down (Patient #6). |

| 6. SW leadership based on empathy | She also gave me information on the transplant. In my case, I did find empathy in that regard, a lot of follow-up, and things were very clear to me (Patient #6). | The social worker and all, shes a person whose way of being I like because shes very straightforward. She tells you something, and youre going to do it for your own good. Why are you going to do it? Because its for your own good, not because you want to. If you dont want to be OK, go ahead, do as you please. But I crossed paths with the social worker, and I saw how she explained things to me, the way she told me things (Patient #5). | She (the social worker) has a way of connecting with patients right from the first time she sees you. Its like she remembers your name because she already knows who you are (Patient #6). |

Discussion

The analysis conducted describes that the SW-PRIST interaction has a positive impact regarding coping with KT for transplant recipients. The actions conducted within PRIST are perceived as support, and these supports have been identified as useful in overcoming family, social, and economic barriers across the entire process.

Patients perceive more support in the pre-transplant phase because this is the time when SW evaluates and activates personal, family, and social mechanisms for transplant preparation. Each patient perceives more or less support based on their individual socioeconomic and family characteristics at the beginning of the process. For example, Indigenous and migrant patients report receiving more support from SW, which stresses the relationship among the vulnerability of certain social groups, the various barriers they face in accessing healthcare, and the need for support across the entire process18.

Participants say that they have received guidance from SW to manage institutional material support across all stages of the transplant process. This guidance helps alleviate the financial burden on their families, which can be significant due to the precarious economic conditions of the population served by HGM. Despite the implementation of free health care, economic barriers and out-of-pocket expenses for post-transplant maintenance therapies still persist. These economic barriers are documented in the medical literature currently available and are associated with worse health outcomes, which suggest the existence of an inverse relationship between socioeconomic status and health measures19. This underlines the importance of continuing to implement actions to counteract these effects for this group of people.

The research describes that the emotional support provided by SW through the implementation of PRIST leads to well-being through constant accompaniment and motivation, making patients feel that the professional "is actually there". In other countries, psychosocial approaches by SW in the organ donation and the entire transplant process are highly relevant1-4,6 maybe because socioeconomic aspects are addressed by health-care systems with more resources. In the Mexican context, significant socioeconomic inequalities demand greater intervention strategies in this regard.

The reported supports for monitoring and leadership by SW are interrelated since the program is implemented through a personalized relationship with constant, empathetic, and direct communication to make sure that actions are actually carried out. This SW leadership in providing support reflects the vision of Person-centred health-care approaches20,21 and person and Person-and Family-Centred Care13. Fig. 2B provides a graphic summary of the analysis presented so far.

The positive evaluation of PRIST suggests that specific interventions should be designed for transplantation care in other hospital settings, customizing actions to the specific needs and characteristics of the population, and to the complexity of the Person-and Family-Centred Care approach.

Based on this evaluation, areas for program improvement can be identified as beneficial for this population: 1. Include sociocultural aspects in the intervention dimensions to develop sensitive actions that should take into account the perspective and experiences of individuals within their context. This means developing cultural competencies by SW; 2. Addition of emotional aspect as a dimension of intervention to strengthen activities related to emotional support and personal and family accompaniment across the entire transplant process; 3. Consider the limitations that institutional dynamics impose on the full implementation of the program.

In conclusion, evaluating PRIST through semi-structured interviews with the patients allowed for a deeper understanding of how each participant perceives and values the social work intervention, while taking into account their socioeconomic context and experience with the transplant. This stresses the importance of conducting qualitative evaluations of health-care interventions.

Conclusion

The PRIST was evaluated positively by the participants. The design across the different phases and dimensions responds to the patients needs and characteristics. The specialized training of SW, and the implementation of programs focused on the individual and his/her family contribute to a better intervention. The implementation of the PRIST in other Mexican hospitals settings should be customized to the needs of the populations served.

Limitations

This study has several limitations: 1. Individuals with graft loss who had to come back to replacement therapy were not included; these experiences could provide information on the role of PRIST in these cases; 2. The perceptions of the transplant health-care team on the value of the SW intervention were not explored; this could help guide intervention lines, or emphasis during program implementation; 3. The working conditions of SW at the hospital setting that could impact the execution of PRIST were not analyzed.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)