Introduction

The resident physician or medical intern is an integral part of the hospital and is the cornerstone for its proper operation1-3.

Improving medical services and training of health personnel requires a number of factors such as improved facilities, technological upgrading and better teaching conditions4,5. The training of medical specialists requires a holistic approach in order to meet the challenges that arise on a daily basis6. At present, medical practice, although it must go hand in hand with teaching in order to gain knowledge, is not always possible7-9. Many factors make it difficult for the resident physician to carry out their duties: lack of educational tools, extremely short study times, professors who are not fully qualified to teach10-16.

Efforts by hospital education departments to incorporate elements that enhance resident teaching are faced with heavy workloads, which hinder learning environments, making it difficult for academic interests to predominate in the training of medical specialists, resulting in academic dropout or tension for time and resources between educational and professional needs17.

It is currently observed that the lack of good study habits and techniques has a direct impact on academic performance3,18. Some authors19 point out that the main predictors of academic performance in medical residencies are the degree of anxiety, motivation and synthesis capacity. All the above makes us understand that this is a complex problem, which is why we focused on studying the habits of medical residents in the specialties of OT and FM, because of the impact they have and the increasing improvement of medical services.

Hence, the objective of this study was to evaluate the study habits in the academic performance of OT and FM residents; then, the causes that lead to poor or good academic performance were also analysed.

Method

An observational, analytical, prospective study was conducted among resident physicians in the OT and FM specialties. All those who agreed to participate and signed the informed consent letter were included. All resident physicians who were on holiday and/or those who did not complete the applied tests, or who were on rotating internship, were excluded.

In order to carry out the research, an online survey was developed using the Google Forms platform, which could be answered at any time. The survey consisted of 72 questions, including a comments section at the end. In the first section of the survey, participants had to fill out an informed consent letter, which was then printed and signed by all of them. In the second section of the survey, questions were asked about general aspects such as age, gender, university degree, specialty and educational institution where the resident physician studied to obtain their degree and their state of origin. In the third section, items assessed study habits in general and in other sections, items specifically related to satisfaction, reading comprehension, memorisation and learning tools. A fourth section assessed socio-economic aspects and family background as well as the resident physician’s own expectations. All questions were answered using a Likert scale. Once the descriptive data of the survey was processed, the questions were weighted from 4 to 1. They were classified into several categories: excellent habits (165-184), good habits (147-164), regular habits (128-146) and bad habits (< 12).

Measures of central tendency and dispersion were used, as well as correlations. The significant statistic value was P < 0.05.

This study was subject to review and approval by the research and ethics committees. All participants were volunteers and signed the informed consent letter. The data collected was downloaded from the cloud and stored in a folder on a computer.

Results

A total sample of 112 participants, 51% male and 21% female, was obtained. In the distribution by specialty (50%) 56 resident physicians per specialty. The mean age was 30.1±3. Distribution by academic year and specialty, for first year FM residents (R1) 25%, second year (R2) 34% and third year (R3) 41%. OT: R1 34%, R2 20%, R3 30% and fourth year (R4) 16%. As for marital status, 75% were single, 24% married/common-law marriage and 1% divorced. Twenty percent had children and 80% had no children (Table 1).

Table 1 General overview of study habits

| n = 112 | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Hours of daily study | |

| < 1 hour | 4 (3.6) |

| 1 hour | 95 (84.8) |

| > 3 hours | 13 (11.6) |

| Daily study as a learning option | |

| Strongly disagree | 3 (2.7) |

| Disagree | 2 (1.8) |

| Agree | 50 (44.6) |

| Totally agree | 57 (50.9) |

| Teachers trained in education. | |

| Strongly disagree | 2 (1.8) |

| Disagree | 1 (0.9) |

| Agree | 41 (36.6) |

| Totally agree | 68 (60.7) |

| Attention to studies (concentration) | |

| Strongly disagree | 4 (3.6) |

| Disagree | 22 (19.6) |

| Agree | 75 (67) |

| Totally agree | 11 (9.8) |

| Distribution of study time during the week | |

| Strongly disagree | 2 (1.8) |

| Disagree | 16 (14.2) |

| Agree | 79 (70.5) |

| Totally agree | 15 (13.4) |

| Breaks during study time | |

| Strongly disagree | 2 (1.8) |

| Disagree | 19 (17) |

| Agree | 77 (68.7) |

| Totally agree | 14 (12.5) |

| Conscious intention to make use of time | |

| Strongly disagree | 1 (0.9) |

| Disagree | 3 (2.7) |

| Agree | 89 (79.4) |

| Totally agree | 19 (17) |

| Pursuit of studies even if not concentrating | |

| Strongly disagree | 1 (0.9) |

| Disagree | 15 (13.4) |

| Agree | 83 (74.1) |

| Totally agree | 13 (11.6) |

The average score for the National Medical Residency Examination (ENARM) was 67.7 (80.4-52.00), while the current average is 91.3 (98.2-73.64).

Regarding the analysis of study habits, it was observed that in general 84.8% study for one hour on average. With regard to daily study as a learning option, 44.6% of respondents strongly agreed and 50.9% agreed. Furthermore, most respondents answered that they split their time throughout the week to study (Table 1).

In the satisfaction survey, 33.9% think that the specialty they are studying is what they expected, 63.4% answered that only sometimes and 84.8% answered that it was the specialty they wanted, while 15.17% do not think so (Table 2).

Table 2 Satisfaction section

| n = 112 | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Expected specialty | |

| Never | 3 (2.7) |

| Sometimes | 71 (63.4) |

| Constantly | 38 (33.9) |

| Thoughts of dropping out of specialty | |

| Never | 77 (68.7) |

| Sometimes | 35 (31.3) |

| Thoughts at the completion of the medical residency | |

| I had a precise idea of what specialty I wanted to pursue. | 49 (43.8) |

| I was undecided between two or three specialities | 53 (47.3) |

| I had no idea which specialty to take | 7 (6.3) |

| I was not interested in pursuing a specialty | 3 (2.7) |

| Current specialty is the one you wished to study | |

| Yes | 95 (84.8) |

| No | 17 (15.2) |

With regard to reading comprehension, 80.4% of the residents stated that they always or constantly understood what they rea., However, 45.5% drew diagrams or charts to organise and complete their studies, as well as concept maps, of which only 41.9% did so to pass their exams. Writing a summary for an exam is the most important memorisation and study technique for 59.8% of the respondents (Table 3).

Table 3 Reading comprehension section

| n = 112 | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Attention to studies (concentration) | |

| Never | 4 (3.6) |

| Sometimes | 51 (45.5) |

| Constantly | 49 (43.7) |

| Always | 8 (7.1) |

| Arrangement of table, desk or their equivalents for study | |

| Never | 5 (4.5) |

| Sometimes | 23 (20.5) |

| Constantly | 27 (24.1) |

| Always | 57 (50.9) |

| Sufficient light when studying | |

| Sometimes | 16 (14.3) |

| Constantly | 38 (33.92) |

| Always | 58 (51.8) |

| Reading comprehension | |

| Sometimes | 22 (19.6) |

| Constantly | 69 (61.6) |

| Always | 21 (18.7) |

| Ability to distinguish the main fundamental points of each topic | |

| Sometimes | 13 (11.6) |

| Constantly | 71 (63.4) |

| Always | 28 (25) |

| Drawing up diagrams or charts for a better organisation of the study | |

| Never | 10 (9) |

| Sometimes | 51 (45.5) |

| Constantly | 30 (26.8) |

| Always | 21 (18.7) |

| Completion of work within the proposed timeframe | |

| Never | 2 (1.8) |

| Sometimes | 38 (34) |

| Constantly | 48 (43) |

| Always | 24 (21.4) |

| Study ahead of time to achieve good results in scheduled exams | |

| Never | 1 (0.9) |

| Sometimes | 36 (32.1) |

| Constantly | 56 (50) |

| Always | 19 (17) |

| Consideration as to whether the form of study is adequate to perform well in an exam | |

| Never | 2 (1.8) |

| Sometimes | 41 (36.6) |

| Constantly | 59 (52.6) |

| Always | 10 (9) |

| Writing a summary when studying | |

| Never | 5 (4.5) |

| Sometimes | 40 (35.7) |

| Constantly | 39 (35) |

| Always | 28 (25) |

| Drawing concept maps when studying | |

| Never | 17 (15.1) |

| Sometimes | 48 (43) |

| Constantly | 34 (30.3) |

| Always | 13 (11.6) |

With regard to memorising, writing down data is one of the most important techniques (82.1%) of the residents who always or constantly do so, as well as paying attention to the classes they attend (86.6%). In comparison, diagrams, charts and schematics or other resources are used by 61.6%. Fifty-seven point seven percent of respondents always or almost always use mnemonics to memorise topics (Table 4).

Table 4 Memorisation section

| n = 112 | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Conducting a general assessment before concentrating on the study | |

| Never | 11 (10) |

| Sometimes | 38 (34) |

| Constantly | 55 (49.1) |

| Always | 8 (7.1) |

| Drafting of important data that are difficult to memorise | |

| Never | 3 (2.7) |

| Sometimes | 17 (15.1) |

| Constantly | 56 (50) |

| Always | 36 (32.1) |

| Mental summary of what you are studying | |

| Never | 2 (1.8) |

| Sometimes | 20 (18) |

| Constantly | 62 (55.3) |

| Always | 28 (25) |

| Memorisation of the most important parts of your reading | |

| Never | 4 (3.6) |

| Sometimes | 24 (21.4) |

| Constantly | 50 (44.6) |

| Always | 34 (30.3) |

| Use of mnemonic techniques to facilitate memorisation of the subject being studied | |

| Never | 11 (9.8) |

| Sometimes | 43 (38.3) |

| Constantly | 40 (35.7) |

| Always | 18 (16) |

| Actual memorisation of the important information on each topic | |

| Never Sometimes | 3 (2.6) 28 (25) |

| Constantly | 68 (60.7) |

| Always | 13 (11.6) |

| Importance of drawing charts, schematics, diagrams and other resources for the improvement of the memorisation process | |

| Never | 8 (7.1) |

| Sometimes | 35 (31.2) |

| Constantly | 41 (36.6) |

| Always | 28 (25) |

| Association of texts that are difficult to memorise with everyday subjects in order to achieve better results | |

| Never | 9 (8) |

| Sometimes | 36 (32.1) |

| Constantly | 42 (37.5) |

| Always | 25 (22.3) |

| The resident pays more attention in class in order to remember topics that are more relevant | |

| Never | 2 (1.8) |

| Sometimes | 13 (11.6) |

| Constantly | 66 (59) |

| Always | 31 (27.7) |

Regarding learning tools, 93.7% responded that they always or constantly attend classes regularly and with a good attitude. As for homework, 85.7% answered that they always or constantly do homework as a learning method. Sixty-two point five percent of respondents answered that they sometimes copy and paste their homework, which represents more than half of the surveyed population (Table 5).

Table 5 Learning tools section

| n = 112 | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Daily and regular class attendance with a willingness to learn | |

| Sometimes | 7 (6.2) |

| Constantly | 50 (44.6) |

| Always | 55 (49.1) |

| Consideration of the teacher’s previous pedagogical training in order to change the way classes are taught | |

| Never | 4 (3.6) |

| Sometimes | 22 (19.6) |

| Constantly | 45 (40.1) |

| Always | 41 (36.6) |

| Undertaking review studies before taking the exam | |

| Never | 2 (1.8) |

| Sometimes | 18 (16) |

| Constantly | 46 (41) |

| Always | 46 (41) |

| Study of the subject before attending class | |

| Sometimes | 31 (27.6) |

| Constantly | 60 (53.6) |

| Always | 21 (18.7) |

| Doing homework as a learning process | |

| Never | 3 (2.7) |

| Sometimes | 13 (11.6) |

| Constantly | 69 (61.6) |

| Always | 27 (24.1) |

| "Copying and pasting" on assignments | |

| Never | 31 (27.7) |

| Sometimes | 70 (62.5) |

| Constantly | 10 (9) |

| Always | 1 (0.9) |

| Taking notes and doing exercises up to date and in order | |

| Never | 4 (3.6) |

| Sometimes | 25 (22.3) |

| Constantly | 66 (59) |

| Always | 17 (15.1) |

| Active participation in class and fulfilment of your role as a student | |

| Never | 1 (0.9) |

| Sometimes | 31 (27.7) |

| Constantly | 66 (59) |

| Always | 14 (12.5) |

| Follow the teacher’s explanations, by taking an active interest and asking questions | |

| Never | 1 (0.9) |

| Sometimes | 24 (21.4) |

| Constantly | 72 (64.3) |

| Always | 15 (13.4) |

| Time management in order to be able to study and achieve better results | |

| Never | 1 (0.9) |

| Sometimes | 32 (28.6) |

| Constantly | 64 (57.1) |

| Always | 15 (13.4) |

| Intense work to improve understanding of the content | |

| Sometimes | 25 (22.3) |

| Constantly | 71 (63.4) |

| Always | 16 (14.2) |

| Working in a team with other colleagues helps you to achieve your personal learning goals | |

| Never | 3 (2.7) |

| Constantly | 63 (56.2) |

| Always | 46 (41) |

| Preferable to be in the classroom where one can listen better and have more attention | |

| Never | 1 (0.9) |

| Sometimes | 10 (8.9) |

| Constantly | 57 (51) |

| Always | 44 (39.2) |

| Necessary complementary material to study properly | |

| Never | 1 (0.9) |

| Sometimes | 20 (18) |

| Constantly | 55 (49.1) |

| Always | 36 (32.1) |

| Study what has been explained and have a creative and critical attitude | |

| Never | 1 (0.9) |

| Sometimes | 11 (9.8) |

| Constantly | 73 (65.1) |

| Always | 27 (24.1) |

| Consult other books in addition to the texts suggested by the teacher | |

| Sometimes | 27 (24.1) |

| Constantly | 56 (50) |

| Always | 29 (25.8) |

| Make every effort to write your papers in a clear manner | |

| Sometimes | 8 (7.1) |

| Constantly | 65 (58) |

| Always | 39 (34.8) |

| Carrying out compulsory activities in time | |

| Never | 2 (1.8) |

| Sometimes | 24 (21.4) |

| Constantly | 63 (56.2) |

| Always | 23 (20.5) |

In the section on academic performance, 94.6% of participants responded that they strongly agree or agree that study habits can influence academic performance. Furthermore, 91.1% responded that they strongly agree or agree that they get a good grade. However, some respondents did not agree or strongly disagree that they have time to study and then perform well on a test (Table 6).

Table 6 Academic performance section

| n = 112 | n (%) |

|---|---|

| The financial situation of the resident does not allow for suitable academic performance | |

| Strongly disagree | 28 (25) |

| Disagree | 41 (36.6) |

| Agree | 25 (22.3) |

| Totally agree | 18 (16) |

| Study habits influence academic performance | |

| Strongly disagree | 1 (0.9) |

| Disagree | 5 (4.5) |

| Agree | 62 (55.3) |

| Totally agree | 44 (39.2) |

| Consideration that study time is insufficient to perform well in a test | |

| Strongly disagree | 6 (5.3) |

| Disagree | 37 (33) |

| Agree | 51 (45.5) |

| Totally agree | 18 (16) |

| Feeling capable of getting a good grade | |

| Strongly disagree | 1 (0.9) |

| Disagree | 9 (8) |

| Agree | 40 (35.7) |

| Totally agree | 62 (55.3) |

| Forgetting the subject when taking an exam, which affects academic performance | |

| Strongly disagree | 18 (16) |

| Disagree | 69 (61.6) |

| Agree | 20 (17.8) |

| Totally agree | 5 (4.5) |

| Constantly asking colleagues about the subject that will be assessed | |

| Strongly disagree | 14 (12.5) |

| Disagree | 49 (43.7) |

| Agree | 45 (40.1) |

| Totally agree | 4 (3.6) |

| Perception that one is studying hard, but grades are not quite good | |

| Strongly disagree | 17 (15.1) |

| Disagree | 58 (51.7) |

| Agree | 30 (26.8) |

| Totally agree | 7 (6.2) |

| Thoughts that one performs better when there is teamwork | |

| Strongly disagree | 5 (4.5) |

| Disagree | 51 (45.5) |

| Agree | 45 (40.1) |

| Totally agree | 11 (9.8) |

| Connection between the time spent studying and grades obtained | |

| Strongly disagree | 2 (1.8) |

| Disagree | 17 (15.1) |

| Agree | 76 (67.8) |

| Totally agree | 17 (15.1) |

| The study methodology is adequate for subsequent good performance in a test and considerations on whether grades could be better | |

| Strongly disagree | 1 (0.9) |

| Disagree | 5 (4.5) |

| Agree | 92 (82.1) |

| Totally agree | 14 (12.5) |

| Learning time is worth living intensely | |

| Disagree | 17 (15.1) |

| Agree | 82 (73.2) |

| Totally agree | 13 (11.6) |

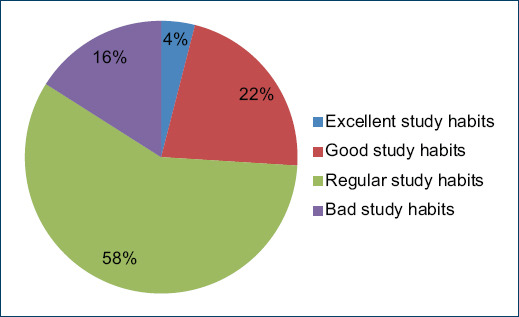

Overall, 58% of respondents had regular habits, 22% had good habits and 18% had bad habits. When analysing the correlation between variables, we observed that there was a correlation between age and average academic performance (p = 0.016) (Fig. 1). Between study habits and marital status, there is a correlation for those who are single (p = 0.004) and married/common-law marriage (p = 0.009), but not for those divorced (p = 0.170). In the correlation between gender and academic performance (p = 0.545), university of study and sum of study habits (p = 0.899), as well as between sum of study habits and year of specialisation (p = 0.994), the correlations were not statistically significant.

Discussion

Academic performance refers to the knowledge acquired throughout residency, which is related to study habits. The scales measuring these habits are most often classified as good or bad, with positive or negative consequences, which are reflected in the students’ grades.

A variety of factors can influence academic performance. Gonzales20 found that in Gynaecology and Obstetrics residents, economic and family factors affect academic performance, regardless of marital status. However, they have been found to influence consistent motivation. We found that the factors that influence OT and MF residents are age and marital status, as they have a direct association with academic performance. We found that at the age of 32±3 years, in our population, there is an association with poorer performance compared to younger resident physicians; most residents at this age are already married and have one or more children.

Eighty-four point eight percent of the medical residents stated that the specialty they are studying is the one they chose, as reflected in the average obtained at ENARM, since most of them are above the general average. In the same section, there is a contrasting point, as an unsatisfactory part is expressed: only 33.6% of the residents think that the specialty they are studying matches their expectations. To a large degree, in this answer given by FM residents and reinforced by data provided by authors such as Sevillano21, it is mentioned that they often opt for this specialty as a second option without giving it the importance it deserves, which explains why these residents show signs of dissatisfaction.

In the section on study habits, it is worth noting that study time is on average one hour. This does not mean that it is a direct aspect that can be linked to academic performance. Because of the external factors surrounding it, such as the quality of the study and the attention given thereto, as attention is the focus of one’s conscious mind in a sustained way on a certain activity or object that allows a clear reflection thereof22.

Likewise, Ortega23 argues that poor academic performance occurs when students do not organise their time, do not develop study plans and do not have the appropriate methodology and study technique.

Therefore, success in studies becomes multifactorial and does not depend directly on intelligence and effort, but also on effective study habits, as the development of academic skills leads to real study and optimal academic results.

It was observed that residents developed regular study habits (58%), and that the most important habit was memorisation. This makes a lot of sense since having taken and passed the ENARM exam and staying in a medical residency requires adequate knowledge acquired in order to put it into practice and to show good academic performance24.

According to the results obtained and the relationship with academic performance (average of the ENARM exam and residency), it was found that there is a direct correlation between the resident physician’s marital status and academic performance. The presence or absence of children did not affect their study skills and, consequently, their academic performance.

We also assessed whether during residency there was an intention to quit, and found responses indicating that they either had never thought of quitting from the specialty (n = 77, 69%) or sometimes (n = 35, 31%).

It has often been observed that when some residents over the age of 30 take the ENARM exam it is their second time round and have difficulty passing it and entering a medical specialty that requires a higher than average score. Therefore, their last option is FM, as the entry score is lower than other specialties. Therefore, many residents choose to take the FM exam as it is their last option to enter the medical specialty. This is also reflected in the answer to the question whether they have ever thought of dropping out of their residency: The answer is "never".

In the case of the FM residents, the reason for dropping out for most of them was that it was not their first choice of specialty. When asked if the specialty they were currently studying was the one they wanted to pursue, 17 medical residents answered that it was not their first choice. Among the causes described in the literature in relation to the present survey, it was observed that those of a family nature17,21 were the most influential on family doctors. In the present study, 6 FM residents were married with children, and this factor partially influences their academic performance, as it is multifactorial.

The dropout rate in the OT specialty is minimal. In the analysis of those residents who responded that they had ever thought of dropping out, the factors that could be inferred were work and family, although this was not directly considered in this study, which could be seen as one of the weaknesses of this research. This could be the basis for a further study to determine the factors that influence their pursuit of OT and FM residency25.

Among the strengths of the study is that it correlates a surgical specialty with a clinical specialty, with a sufficient sample of medical residents.

As for weaknesses, there was no contrast with other medical and surgical specialties, where most residents make their first choice to enter a medical residency. This contrasts with one specialty (FM) that was not their first choice of entry and relates to residents who have taken the ENARM exam several times, so there is a selection bias and a manoeuvre bias.

We intended to conduct a multicentre study of all medical residency training sites in the state and outside the state of Puebla. The extension of the sample size and the analysis of other factors such as family, economic and social factors that can influence academic performance in a surgical specialty as well as clinical specialty. In addition, an analysis of workload and care, as well as a purposive search for stress and anxiety, as these factors may also affect academic performance within the specialty. It would also be important to analyse the use of ICT access and academic infrastructure, as well as the time and educational training of teachers and clinical practice tutors in the medical practice of resident physicians.

We also propose a practice analysis and evaluation of knowledge transfer horizontally (resident to resident) and vertically (clinical practice tutor to residents).

Conclusion

Age and marital status have a direct correlation with academic performance, while gender, university of study and year of residence do not. It is worth highlighting that an association was found between both specialties and the development of different study habits, due to the fact that the focus of each specialty is different, which requires different study habits. In general, TO and FM residents have regular study habits.

In terms of satisfaction, most residents felt that they were doing the specialty that was their first choice. A smaller percentage considered that they did not choose the specialisation they had planned (FM); on the other hand, a large percentage indicated that sometimes this was what they expected.

In the study habits section, it was found that the study time was adequate. However, there were difficulties in concentrating during the study and in the distribution of the study time.

In the reading comprehension section, it was inferred that this is the most difficult study habit for the residents, as they found it difficult to understand and distinguish the main points of the topics they have read.

In the memorisation section, we observed that they presented problems in associating information with everyday affairs and using mnemonic techniques to facilitate information. However, they again displayed mastery of learning strategies oriented towards this habit.

As far as learning tools are concerned, the classroom has been shown to complement medical training. A negative aspect found is that most of them copy and paste information in their homework, as they deem it unnecessary, and they do not look for other sources of information to enrich their knowledge.

In conclusion, knowledge of study habits is not the only factor predisposing to academic performance, as there are other factors, which have not been analysed in this research. We propose to carry out another study where a multifactorial analysis is considered, that includes academic, social, family, professional and economic factors, and especially purposive search for stress and anxiety, as well as a multicentre study where other clinical and surgical specialties are analysed and contrasted.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)