Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is a global health problem due to lifestyle changes, especially in middle- and high-income countries, which is why in the past 15 years it has been the leading cause of death, with nearly 15.2 million deaths worldwide in 20161-3. In Mexico, together with the cases of metabolic syndrome and the higher incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiac pathologies in our population occupy first place as a cause of death in relation to chronic degenerative pathologies, with 18.6% of cases reported in 20144,5.

Regarding surgical treatment options, the most recent American report published by The Society of Thoracic Surgeons in 2018, highlights that the most frequent surgery was coronary artery bypass grafting at 54%, followed by single or multiple valve replacement surgery, which reached 24%. Single aortic valve replacement (transcatheter aortic valve replacement) accounted for 10% of all cardiac surgeries, followed by mitral valve replacement (MVR) at 2%, with other multiple valve replacements6, a similar situation found in Europe globally according to a report by the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. However, in Spain, valve surgery is the most frequent with 48% followed by coronary revascularization with 25%7-9. In Mexico, the main procedure performed is valve replacement, ranging from 48.5 to 51.9%, followed by coronary revascularization surgery with 18%10,11.

From the first valve surgery in 1945, performed by Dr. Bailey12,13 for mitral stenosis, to the first valve placed in the aortic position in 1952, performed by Dr. Hufnagel and its refinement by Dr. Starr in 196213-15, rheumatic pathology was the main cause of valve deterioration followed by the degenerative process. Although acute rheumatic fever has declined in the USA and Europe, chronic cases of inactive rheumatic heart disease remain a cause of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, mainly in middle- and low-income countries, with up to 25% of patients having isolated mitral stenosis, 40% double mitral lesions and followed by multiple valve involvement16-18. However, in some series and according to socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, degenerative pathology prevails over rheumatic pathology, if we consider both aortic insufficiency and stenosis and mitral insufficiency, and mitral insufficiency, nevertheless mitral stenosis is associated with 85% of rheumatic disease.6,7,9,18.

Against this background, there are several options for surgical treatment ranging from replacement to surgery and, in recent years, interventional valve implantation, in each situation with specific indications19. In the first case, mortality ranged from 2.2% to 4.9% in the American report and European report, it reached 3.4% in single valve replacement and in cases of multiple valve replacements or associated with another procedure it ranged from 4.9% to 9.5%, a very similar situation presented in our country where it reached 7.9%6-7,10. Morbidity related to variables such as reoperation, mediastinitis, renal failure, and prolonged ventilation, among others, represented a risk between 4.8% and 17.1%, with patients undergoing mitral valve surgery being the most affected6,10. In our country, experience gained over the decades at the National Institute of Cardiology reported a survival rate of 88.8%. This includes surgeries mainly on the mitral valve apparatus, followed by the aortic valve and finally multiple valve replacements, with a predominance of mechanical valve placement, a similar situation in Chile and the United States of America, where around 81% and 66%, respectively, were placed, with a predominance of the aortic position20-22.

The aim of this article was to identify the clinical and surgical outcomes of patients undergoing valve surgery and their survival at post-surgical follow-up.

Material and methods

We conducted an observational, cross-sectional, descriptive, retrospective, and retrolective study, where the inclusion criteria were the complete records of patients of any gender and over 18 years of age treated by a surgical procedure involving one or more heart valves. The study took place at the Cardiothoracic Surgery Unit of the General Hospital of Mexico Dr. Eduardo Liceaga, in the period from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2018. Our variables of interest were demographic characteristics, cardiovascular risk factors, functional class, diagnoses, surgical prognostic scales, valve prosthesis characteristics, post-surgical complications, need for surgical reintervention, death, and causes of death.

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS (IBM, Chicago, IL. USA) V.24 for Windows. The study of the general data was performed using descriptive statistics, analysis of correlations, and mean differences with their 95% confidence intervals, logistic regression was performed to evaluate the presence of the outcomes of interest: complications and death, and the analysis of survival, using the Kaplan-Meier test. Statistically significant differences were considered to exist when p ≤ 0.05.

Results

A total of 163 records of patients undergoing valve surgery over a 5-year period were analyzed, in which 54.6% were male and 45.4% female, with a mean age of the entire sample of 54 years ± 14 (Table 1). The majority came from the State of Mexico (41%) and Mexico City (31%), followed by states in the central-southern region: Guerrero (7%), Morelos (6%), Oaxaca (3%), Veracruz (3%), Puebla (1%), and Chiapas (1%), and < 1% from Sinaloa, San Luis Potosí, Querétaro, Guanajuato, Michoacán, and Zacatecas.

Table 1 Characteristics of patients undergoing valve surgery

| Variable | Mean (± SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 54 (± 14) | (18-85) |

| Functional class difference | −1.1 (± 0.8) | (−2-0) |

| Body mass index | 26.7 (± 4.3) | (17.8-46.7) |

| EuroSCORE II | 2.3 (± 2.3) | (0.5-23.1) |

| STS score-mortality | 2.3 (± 4.3) | (0.3-50) |

| STS score-morbidity | 13.2 (± 8.1) | (3.1-66.2) |

| Prostheses per patient | 1 (± 1) | (1-3) |

| Inpatient days | 21 (± 14) | (5-110) |

| Post-surgical follow-up time (months) | 24.2 (± 19.7) | (0-65) |

Test: Mean, standard deviation, and ranges.

The cardiovascular risk factors documented in relation to the total number of cases were: systemic arterial hypertension (n = 80; 49.1%), sedentary lifestyle (n = 63; 38.7%), type 2 diabetes mellitus (n = 41; 25.2%), smoking (n = 41; 25.2%), dyslipidemia (n = 29; 17.8%) and obesity (n = 103; 63.2%), stratified according to body mass index into overweight (n = 79; 48.5%), Grade I overweight (n = 17; 10.4%), Grade II overweight (n = 4; 2.5%), and Grade III overweight (n = 3; 1.8%). Subjects had an average body mass index of 26.6 ± 4.2. About 96.3% of patients had no previous history of cardiac surgery.

Regarding all surgeries, the most frequently operated valve was the aortic valve in its different forms of presentation: stenosis, insufficiency, or double lesions followed by mitral and tricuspid valve disease (Table 2). The main etiologies were identified as degenerative (46%), rheumatic (27%), endocarditis (14.7%), bicuspid valve (11.7%), and prosthetic dysfunction (0.6%).

Table 2 Diagnoses of patients who underwent heart valve surgery

| Diagnostics | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Aortic stenosis | 43 | 26.4 |

| Aortic insufficiency | 14 | 8.6 |

| Mitral stenosis | 7 | 4.3 |

| Mitral insufficiency | 4 | 2.5 |

| Tricuspid insufficiency | 2 | 1.2 |

| Double aortic lesion with predominant stenosis | 32 | 19.6 |

| Double aortic lesion with predominant insufficiency | 6 | 3.7 |

| Double mitral lesion with predominant stenosis | 8 | 4.9 |

| Double mitral lesion with predominant insufficiency | 11 | 6.7 |

| Mitral stenosis plus tricuspid insufficiency | 2 | 1.2 |

| Mitral regurgitation plus tricuspid regurgitation | 6 | 3.7 |

| Double aortic lesion with predominant stenosis plus mitral insufficiency | 6 | 3.7 |

| DOMV with predominant stenosis plus double aortic lesion with predominant stenosis | 4 | 2.5 |

| DOMV with predominant insufficiency plus double aortic lesion with predominant stenosis | 5 | 3.1 |

| DOMV with predominant insufficiency plus double aortic lesion with predominant insufficiency | 9 | 5.5 |

| Double aortic lesion with predominant insufficiency plus DOMV with predominant insufficiency plus tricuspid insufficiency | 4 | 2.5 |

| Total | 163 | 100.0 |

Test: Frequencies and percentages.

In relation to functional class according to the New York Heart Association (NYHA) scale, preoperatively patients were mainly in Stage II (44.2%), Stage III (52.1%), and Stage IV (3.7%). After valve correction, functional class improved (Table 1), with Stage I 62.6%, Stage II 30.1%, and Stage III 7.3%.

Early mortality according to the EuroSCORE II was on average 2.3 ± 2.3, and according to the STS score for mortality was 2.3 ± 4.3, and the prognosis for morbidity-STS score was identified as 13.2 ± 8.1 (Table 1).

The procedures performed were in accordance with the pre-surgical diagnoses. The main surgery performed was single aortic valve replacement (57.7%) followed by double or triple valve procedures (aortic plus mitral: 14.7% and aortic plus mitral plus tricuspid: 2.5%). Then, single mitral replacement surgery (19%), mitral plus tricuspid (4.9%), and lastly tricuspid annuloplasty, with tricuspid annuloplasty being performed with the use of tricuspid rings and only one case of tricuspid valve replacement (1.2%). We determined that the average number of prostheses used per patient was one, with mechanical prostheses being St. Jude® and biological prostheses distributed among St. Jude®, Edward®, and Medtronic®, while tricuspid rings were Medtronic®. There was no dysfunction of the valve prostheses implanted by our unit.

Post-surgical complications occurred in 26.4%, distributed in respiratory infections (12.9%), post-surgical bleeding (11%), and sepsis (2.5%) with the need for reoperation in 18 patients (11%) due to higher than usual bleeding during their post-surgical evolution. In the latter group, bleeding occurred mainly after aortic valve replacement, performed in 13 patients (72.2%), corresponding to 12 aortic valve replacements. In all cases, the diagnosis of aortic stenosis was associated with aortic stenosis (seven aortic stenosis, five with double aortic lesion with predominantly stenosis, and one with double aortic lesion with predominantly stenosis plus mitral insufficiency) and the other cases occurred in 5 (27.8%) MVRs. The mean number of hospitalization days was 21 ± 14, in relation to the waiting time to obtain surgical material by the patients.

The main cause of death was ventricular failure (9.2%), followed by septic shock (6.1%), multiple organ failure (4.3%), myocardial infarction (3.7%), and lethal arrhythmias (1.8%). Post-surgical follow-up was 65 months with a mean follow-up of 24.2 months ± 19.7. Post-surgical complications, death, and causes of death were contrasted with demographic characteristics, improvement in functional class, surgical risk scales for cardiac surgery, inpatient days, and post-surgical follow-up time in months. No significant statistical difference was found (p ≤ 0.05) in relation to improvement in functional class in relation to improvement in functional class, inpatient days, and post-operative follow-up time, associated with a lower probability of post-operative complications and death (Table 3).

Table 3 Relationship between complications, death and causes of death in patients undergoing valve surgery

| Variables | Mean (± SD) | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Higher | |||

| Post-surgical complications | ||||

| Improvement of functional class | −1.1 (± 0.7) | 0.001 | −1.2 | 23.5 |

| Inpatient days | 21 (±14) | 0.0001 | 21.1 | 27.2 |

| Post-surgical follow-up (months) | 24.2 (±19.7) | 0.0001 | ||

| Death | ||||

| Improvement of functional class | −1.1 (± 0.7) | 0.001 | −1.2 | 23.5 |

| Inpatient days | 21 (±14) | 0.0001 | 21.1 | 27.2 |

| Post-surgical follow-up (months) | 24.2 (±19.7) | 0.0001 | ||

| Causes of death | ||||

| Improvement of functional class | −1.1 (± 0.7) | 0.0001 | −1.2 | 23.5 |

| Inpatient days | 21 (±14) | 0.003 | 21.1 | 27.2 |

| Post-surgical follow-up (months) | 24.2 (±19.7) | 0.0001 | ||

Test: ANOVA.

Student's t-test analysis found statistically significant differences in functional class improvement (p = 0.0001) and post-surgical follow-up time (p = 0.0001) between living patients and those who died after valve replacement surgery so that these two factors determined a difference in mortality in these groups (Table 4).

Table 4 Factors related to the condition of patients undergoing valve surgery

| Variable | Current status | Frequency (n) | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Higher | ||||

| Age | Alive | 122 | 0.2 | −4.5 | 5.9 |

| Dead | 41 | −4.9 | 6.3 | ||

| Improvement of functional class | Alive | 122 | 0.0001* | −1.6 | −1.2 |

| Dead | 41 | −1.6 | −1.2 | ||

| Body mass index | Alive | 122 | 0.1 | −1.4 | 1.7 |

| Dead | 41 | −1.2 | 1.4 | ||

| Inpatient days | Alive | 122 | 0.1 | −2.8 | 7.6 |

| Dead | 41 | −3.4 | 8.2 | ||

| EuroSCORE II | Alive | 122 | 0.03* | −0.9 | 0.8 |

| Dead | 41 | −0.6 | 0.5 | ||

| STS score-mortality | Alive | 122 | 0.3 | −2.0 | 1.1 |

| Dead | 41 | −1.4 | 0.5 | ||

| STS score-morbidity | Alive | 122 | 0.3 | −3.5 | 2.2 |

| Dead | 41 | −3.0 | 1.7 | ||

| Prostheses per patient | Alive | 122 | 0.4 | −0.2 | 0.1 |

| Dead | 41 | −0.2 | 0.1 | ||

| Post-surgical follow-up (months) | Alive | 122 | 0.0001* | 22.3 | 33.4 |

| Dead | 41 | 23.0 | 32.7 | ||

*Statistically significant difference

Test: Student's t-test

Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to measure surgical risk scales and post-surgical follow-up time, in relation to age, improvement in functional class, body mass index, inpatient days, and number of prostheses per patient. To establish the impact on the result obtained; a direct relationship was found between surgical risk through the EuroSCORE II and inpatient days (p = 0.022).

Concomitantly, Spearman correlations were performed to measure the affinity between cardiac surgery risk scales, post-surgical follow-up time and death in relation to etiology, pre-surgical functional class, and post-surgical functional class. This included cardiovascular risk factors such as age, gender, systemic arterial hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, sedentary lifestyle, smoking, and history of previous cardiac surgery to determine the impact on these variables. A direct relationship of surgical risk through EuroSCORE II and STS score with post-surgical functional class (p = 0.026) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (p = 0.021) was found. According to the STS score, morbidity was related to age (p = 0.04) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (p = 0.007), on the other hand, pre-surgical functional class (p = 0.0001) was related to death.

The current status (alive or dead) of the patients was measured with an adequate calibration through logistic regression with Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p = 0.007) in relation to post-surgical functional class, improvement in functional class after surgery, the Society of Thoracic Surgery predictive scale for mortality, and post-surgical complications. A significant statistical difference was found (p < 0.01) in the improvement of functional class and the different post-surgical complications observed, with no influence on the current status, in relation to the predictive scale of surgical risk, post-operative functional class, and post-operative reintervention (Tables 5 and 6).

Table 5 Summary of the Hosmer-Lemeshow test model and goodness-of-fit for death by functional class, mortality, and post-surgical complications

| Step | Summary of the model | Hosmer-Lemeshow test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −2 log likelihood | Cox and Snell R-squared | Nagelkerke R-squared | χ2 | gl | p | |

| 1 | 24.8a | 0.6 | 0.9 | 21.1 | 8 | 0.007* |

aThe estimation ended at iteration number 20 because the maximum iterations have been reached. The final solution cannot be found. Statistically significant difference.

Test: Hosmer-Lemeshow test-Binomial logistic regression.

Table 6 Logistic regression of death by functional class, mortality, and post-surgical complications

| Variables | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Higher | ||

| STS score-mortality | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| Post-surgical functional class | |||

| NYHA I | 0.7 | 0 | 0 |

| NYHA II | 0.9 | 0.0001 | 0 |

| NYHA III | 0.9 | 0.0001 | 0 |

| Improvement of functional class | 0.0001* | 16.4 | 11392.5 |

| Post-surgical complications | |||

| None | 0.002* | 0 | 0 |

| Bleeding | 0.0001* | 0.0001 | 0.007 |

| Respiratory infection | 0.007* | 0.0001 | 0.1 |

| Sepsis | 0.003* | 0.0001 | 0.04 |

| Post-surgical reintervention | 0.8 | 0.03 | 52.2 |

*Statistically significant difference.

Test: Binomial logistic regression.

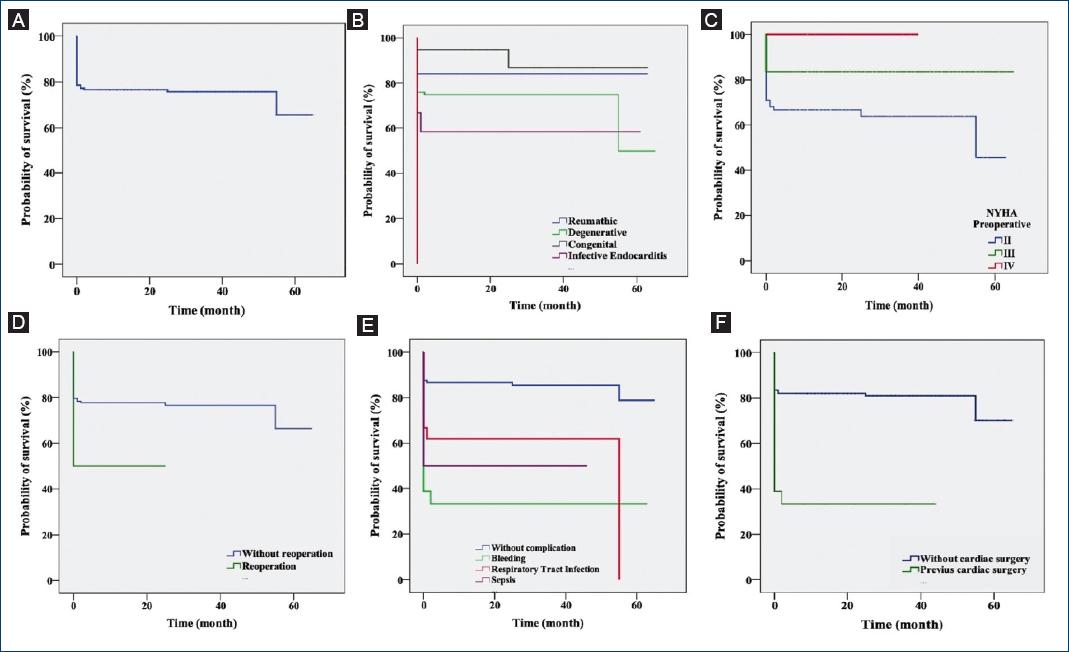

Survival analysis was then performed and overall survival reached 70% in the 60 months following valve replacement surgery, with survival at the end of the 1st year being close to 75% (Fig. 1A). Thus, those with a diagnosis of congenital valve disease were found to have better survival, but showed a significant difference after 20 months of follow-up, a situation that did not occur in patients with rheumatic etiology who maintained a constant survival of over 80% and those diagnosed with endocarditis had worse outcomes with survival of < 60% (Fig. 1B). In relation to their pre-surgical functional class, those in NYHA Stage III maintained minimal variations compared to patients in NYHA Stage II who had decreases in survival, this is in concordance with the surgery that improved their functional class, increasing the number of patients in this stratification (Fig. 1C). On the other hand, patients with a history of previous cardiac surgery had a 50% survival at 2-year follow-up compared to those without, whose survival was close to 60% (Fig. 1D). Finally, in relation to their post-surgical complications, those who had post-surgical bleeding had a lower survival compared to infectious complications, which corresponds to the lower survival in those who underwent reoperation (Figs. 1E and F).

Discussion

Changes in health dietary habits, as well as non-modifiable factors, have led to an increase in cardiovascular health-related ailments, a situation that is no different in our country and which in this case we have determined situations that fall within the scope of valvular pathology.

Although recent reports from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery6-9 emphasize that the main surgery performed is coronary revascularization, our results agree with Vásquez et al. who found that the main cardiac surgical procedure in Mexico is valve surgery11. Similarly, in accordance with Juárez et al. from the National Institute of Cardiology, who reported a survival rate of 88%20, in patients who underwent valve replacement surgery; in our case, there was about 80% in the first 4 years of follow-up, decreasing to about 70% from the following year onward, in terms of overall survival.

We found that the main replacement performed was aortic valve replacement in 64.1% of cases, either as a single procedure or in combination with other valves, a situation similar to the American and European reports6-9, which ranged from 24 to 48% of cases. It was also identified that the main etiology in our study was degenerative, followed by rheumatic and infectious, where the results disagree with Villavicencio et al.21, as they placed congenital or bicuspid as the first cause, however, their series mainly studied the aortic valve; but coinciding with the other causes found by us.

Regarding complications, the literature reports between 4.8% and 17.1%, which our results disagree with, showing 26.4%, with respiratory infections being the most frequent, followed by post-surgical bleeding and sepsis, but it is important to note that during the period reported, there were no cases of mediastinitis as described in other reviews6-10.

Accordingly, Rodriguez et al. described variables that are related to mortality in cardiac surgery10, so we contrasted the main factors involved in the evolution, determining that the lower risk of complications and death was related to the improvement of functional class (p = 0.001), shorter hospital stay (p = 0.0001), and longer post-surgical follow-up (p = 0.0001). Thus, confirming that there were statistically significant differences with patients who currently continue to undergo cardiac surgery, shorter hospital stay (p = 0.0001), and longer post-surgical follow-up (p = 0.0001), confirming that there were statistically significant differences with patients currently continuing in their consultations (p < 0.05).

When considering the days of hospitalization, which averaged 21, it is worth noting that this was mainly due to the logistics of acquiring surgical material in a public hospital without the full supply from the state or taxpayers as in other Mexican entities, rather than due to complications or unfavorable events related to the surgical event.

We definitely propose that before establishing the post-surgical complications, which in some cases are the determinant of death as we have already demonstrated (p < 0.05), it would be worthwhile to raise awareness that the main cardiovascular risk factors that we found in our patients. These factors include age, gender, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and systemic arterial hypertension, led to an increase in the scores of the predictive scales of surgical risk and that, in addition to the complications, in some cases, determined a fatal outcome.

Conclusions

At the General Hospital of Mexico Dr. Eduardo Liceaga, a complex population is cared for, regarding their underlying pathologies and comorbidities, as well as their socioeconomic status and clinical status at the time of hospital referral. Therefore, in this first study of the Cardiothoracic Surgery Unit, we determined an initial diagnosis of the situation of the most recent years in cardiac patients and publish the response we had to one of the most frequent cardiovascular pathologies in our country.

Our results are similar to those observed in the national and international literature, with minor differences that will need to be measured again in a timely manner in the future, to make a comparison with other national and international reference centers and thus determine impact actions in the care of our heart patients.

Finally, the survival rate presented in this study shows the work of the "Heart Team" of our institution and that over the next few years, we intend to improve and get even closer to the statistics of the major world centers where cardiac surgery is performed.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)