Introduction

Symptoms due to gallstone disease are a leading gastrointestinal cause for hospitalization and health-care utilization1.

Definitive treatment consists of performing cholecystectomy, since the risk of developing recurrent symptoms or complications rises to 70% 2 years after the initial presentation. Whenever possible, the laparoscopic approach is preferable over open surgery. Although there are no differences in terms of mortality and complications, the laparoscopic approach reduces hospital stay and shortens the period of convalescence. The complication rate is approximately 5% and includes bile duct injury, bile leakage, hemorrhage, and infection of the surgical wound. The operative mortality rates between 0% and 0.3%2.

Outpatient surgery, defined as one in which the patient may be discharged 12 h after the surgical act, requires clinical practice guidelines that allow the current surgeon to begin or improve their practice3.

In 1995, Dr. Kehlet’s group published the results of a multimodal perioperative care protocol in patients undergoing elective colectomy4, which was later called enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS)5. Since then, this multimodal approach has been applied in other types of elective surgeries, including cholecystectomy6.

The ERAS protocol includes a combination of techniques in pre-operative management in elective surgery, aimed to attenuating surgical stress and improving post-operative recovery. It consists of optimizing pre-operative preparation for surgery, reducing stress response, avoiding post-operative ileus, accelerating recovery with return to normal function, as well as an early recognition of recovery failure and intervention if necessary7.

Our aim was to evaluate the success rate of ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy with an ERAS protocol in a prospective cohort of patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis.

Materials and methods

We performed a prospective cohort of patients with symptomatic gallstones who underwent elective surgery on an outpatient basis at the General and Endoscopic Surgery Division of the General Hospital “Dr. Manuel Gea González” from July 2015 to September 2017.

Patients with a diagnosis of symptomatic gallstones treated with ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy with an ERAS protocol of any sex, aged between 15 and 75 years, with an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification I or II were included in the study. Pregnant women, foreign patients, those with uncontrolled comorbidities, anticoagulant’s user and poor family support were excluded from the study. Elimination criteria included those who retract their consent or did not have post-operative follow-up.

The primary end point was the success rate of ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy, defined as in which the patient was able to be discharged on an outpatient basis (within 12 h), without hospital readmission and no post-operative complications at 30 days follow-up. Secondary end points studied were intraoperative complications, post-operative complications, duration of post-operative hospital stay, unplanned hospital admission, and patients’ satisfaction.

Laparoscopic cholecistectomy with ERAS protocol

PRE-OPERATIVE CARE

Information about the principles of ERAS protocol was given to patients and their caregiver.

An exhaustive pre-operative evaluation by the anesthesiology group was performed for all patients. Patients were admitted on the morning of the surgery. Pre-operative treatment with crystalloid isotonic solution (calculated according patient’s requirements), antibiotics (cefalotine 1 g intravenous [IV]), standard gastric prophylaxis (omeprazole 40 mg IV), and opioid-sparing analgesia (acetaminophen 1 g IV and ketorolac 30 mg IV) were applied.

INTRA-OPERATIVE CARE

Balanced general anesthesia, strict control of fluid therapy, prevention of hypothermia, and adequate analgesia were given to all patients to reduce metabolic stress response.

The surgical technique included three trocars. All port sites were infiltrated before incision using 0.5% bupivacaine. Nasogastric tubes or drains were not inserted. Anti-emesis prophylaxis was achieved with dexamethasone (4 mg IV) and ondansetron (8 mg IV).

POST-OPERATIVE CARE

Patients were taken to a recovery area adjacent to the operating room, where they were monitored and recordings of their vital signs and pain using the visual analog scale (VAS) was obtained. At this stage, antibiotics were suspended and opioid-sparing multimodal analgesia was given (acetaminophen 1 g IV and ketorolac 30 mg IV); in cases of post-operative nausea and vomiting ondansetron was administrated. After reaching a satisfactory level of consciousness, patients were encouraged to walk around freely and start oral intake with clear liquids.

Discharge criteria included pain controlled with oral analgesics (VAS < 4), adequate tolerance to oral intake, ambulation, capacity of micturation, hemodynamic stability, fully mental recovery, surgeon’s approval, and absence of nausea and vomiting. Patients were reviewed and given home post-operative instructions, with special emphasis on alarm symptoms.

Follow-up

All patients were followed up with a phone call on post-operative day 3 and clinical appointments on post-operative days 7 and 30. Post-operative complications, readmissions, and reoperations were recorded if they presented during the 30-day follow-up period.

Sample size

A power calculation was performed using a ninety percent of expected success rate of ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy, with and alpha error = 0.05 and precision of 5%. One hundred and thirty-eight patients were calculated, with a 10% of expected loss, 152 patients were obtained.

Our data were summarized as the means (with minimum and maximum values) or number of patients (percentages).

SPSS version 18.0 for MAC (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA) was used for analyzing data.

Results

From July 2015 to September 2017, a total of 174 patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis were evaluated, 14 patients were also eliminated because they did not have postoperative follow-up. Therefore, we continued the study with 160 patients, of which 134 were women (83.7%) and 26 (16.2%) were men. Baseline demographic data are shown in table 1.

Table 1 Patients baseline characteristics

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| n (patients) | 160 patients |

| Sex (female:male) | 134 (83.7):26 (16.2) |

| Mean age (years) | 36.8 (15-73) |

| ASA I | 150 (93.7) |

| ASA II | 10 (6.2) |

| Abdominal surgery history | 89 (55.6) |

| Medical history | |

| Diabetes | 2 (1.25) |

| Hypertension | 5 (3.12) |

| Other | 4 (2.5) |

| None | 149 (93.1) |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists

Intraoperative findings were: 135 patients with cholelithiasis (84.3%), 15 patients with unexpected acute cholecystitis (9.3%), six patients with empyema (3.7%), and four patients with gallbladder hydrops (2.5%). The average post-operative hospital stay in hours was 4.6 ± 7.3 (SD) (Table 2).

Table 2 Surgical findings and characteristics

| Characteristics | n (min-max) |

|---|---|

| Duration of surgery (minutes) | 63.8 (25-150) |

| Bleading (ml) | 30.1 (5-100) |

| Mean postoperative VAS | 4.1 (0-10) |

| Mean postoperative stay (hours) | 4.6 (1-95) |

| Surgical findings | n (%) |

| Cholelithiasis | 135 (84.3) |

| Unexpected Acute Cholecystitis | 15 (9.3) |

| Empyema | 6 (3.75) |

| Gallbladder Hydrops | 4 (2.5) |

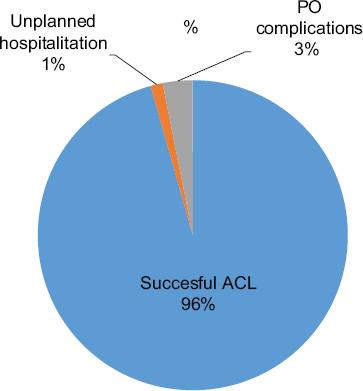

On the other hand, unplanned hospital admission was reported in two patients (1.2%), 1 who underwent pain that did not subside with oral medication and 1 (0.6%) patient required surgical management due to bleeding (0.6%); both patients were diagnosed with gallbladder empyema during surgery. Post-operative complications were seen in 5 (3.1%) patients: 4 (2.5%) of these patients had a diagnosis of residual abscess and 1 (0.6%) patient developed acute pancreatitis. Thus, a success rate of 95.6% (153 patients) was obtained in this protocol (Fig. 1). Other points analyzed were intraoperative complications, which were not found in this protocol, reporting a total of zero cases (0%). Conversion to open surgery was not registered in this protocol.

Figure 1 Success rate of ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy (ALC). Unplanned hospitalization rate account for 1.2% and post-operative complications for 3.12% of our sample. Successful ACL was feasible in 96% of our patients.

Furthermore, we evaluated patients’ satisfaction with medical care, hospital length stays, and information received by our team. All of them showed a rate close to 99%.

Discussion

Successful ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy (ALC) is one in which the patient can be discharged within 12 h post-operative period, without hospital readmission and no postoperative complications at 30 days. In our study, unplanned admission (1.2%), intraoperative complication including conversion rate to open surgery (0%) and postoperative complication, including surgical site infection and acute pancreatitis (3.1%), account for a total of 4.3% of our sample, achieving a success rate of 95.6% for ambulatory cholecystectomy using an ERAS protocol.

Several studies mention their success rate for this procedure8-12 (Table 3). For instance, Jiménez and Costa11 described their experience with 100 cases of outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy subjected to a protocolized anesthesia that included intraperitoneal and parietal use of local anesthesia achieving excellent pain control, the main cause of hospitalization. The frequency of outpatient discharge was 96%. The mean hospital stay of the patients was 7.4 h (7-9.6 h). The morbidity and mortality of the series were 0%; and conversion rate to laparotomy in the series was 0%. No patient required readmission after discharge, and 97% of the patients were very satisfied with the procedure.

Table 3 Several studies were success rate and degree of satisfaction of ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy was reported

| Study (year) | Number of patients | Success rate of ALC (%) | Unplanned hospitalization (%) | Readmission (%) | Reintervention (%) | Conversion to open surgery | Degree of satisfaction at 7th day post-operative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akoh et al.8 | 258 | 69.0 | 31.0 | 5.0 | - | - | - |

| Lezana-Pérez et al.9 | 141 | 82.0 | 18.4 | 3.5 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 82 |

| Soler-Dorda and Marton-Bedia10 | 511 | 70.0 | 30.0 | 2.8 | 1.2 | 3.3 | - |

| Jiménez and Costa11 | 100 | 96.0 | 4.0 | 0.0 | - | 0 | 97 |

| Sala-Hernández et al.12 | 164 | 92.8 | 5.5 | 1.8 | - | 1.2 | 87.10 |

| Mendoza-Velez et al. | 160 | 95.6 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0 | 99 |

ALC: ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy

Tang and Dong13 performed a meta-analysis comparing short-stay surgery versus night-stay surgery in patients with lithiasic cholecystitis after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. It included 12 studies, with a total of 1,430 patients, 650 were classified as ambulatory cholecystectomy and 780 as overnight stay surgery. Within the results they reported morbidity of 5.2% and 6% for the group of short stay surgery and night stay surgery, respectively, being statistically not significant. Regarding prolonged stay or unplanned hospital admission, they found 13.1% in the ambulatory surgery group. The main causes were conversion to open surgery, nausea or vomiting that did not give way to medications, pain, and use of drainage. While in the overnight stay group, a 12.1% length of hospital stay was found for the same reasons, being statistically not significant between groups. The percentage of readmission once hospital discharge was 0-4.8% in the short stay group, while in the overnight stay group it was 0-5.2%, the main diagnoses in both groups being infections, pancreatitis, and biliary leak. However, this was also not statistically significant. Other points that were analyzed were the quality of life on the day of surgery and the time of return to work activities; however, the differences were not statistically significant. The authors concluded that outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy is safe, effective and cheaper and can be performed without major problems in selected patients.

Lezana et al.9 analyzed the effectiveness and quality of outpatient cholecystectomy versus conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy management. In this study, no intervention was performed regarding pain control. The overall satisfaction index was 82% and the satisfaction indicator for the care received was 81%, both above the previously set standard. Regarding the other parameters analyzed (mortality, morbidity, reinterventions, readmissions, and stay) there was no difference between the two groups as in other studies cited.

In our study, the degree of satisfaction expressed was either excellent or very good in 99% of our sample on the 7th post-operative day. We valued medical care (99.3%), hospital stay length (99.3%), and information received before procedure (98.7%), achieving a great acceptance between our patients.

Based on this study, we intend to carry out new prospective studies to assess outpatient management with ERAS protocol in patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis.

Conclusion

The performance of ALC with an accelerated postoperative recovery protocol in patients with symptomatic gallbladder lithiasis has a significant success rate in the period investigated and similar to the reported in international literature. Our study supports the safety, reliability, and possibility for implementation of routine ALC with ERAS protocol, with a demonstrated high degree of patient satisfaction. Our data advocate the inclusion of ALC as a treatment of choice for symptomatic cholelithiasis that minimizes hospitalizations. However, our sample is limited to one center and no control group was followed.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)