Introduction

Surgical suturing is a fundamental skill needed by all surgeons. Therefore, it is necessary to have detailed knowledge about its mechanics principles. In our experience gained through hosting over 60 surgical suturing courses during the last five years, medical students often complain that every surgeon teaches them the same technique in a different manner and it is hard to recognize who manages the correct way. We believe that this review, based on the previous work of many skillful surgeons, provides all the necessary details needed for correct surgical suturing techniques.

Correct skin suture

The essential variables for the correct skin suture are: 1) leveled conjunction of both wound edges, 2) minimal trauma caused by suture placement, and 3) adequate suture tension.

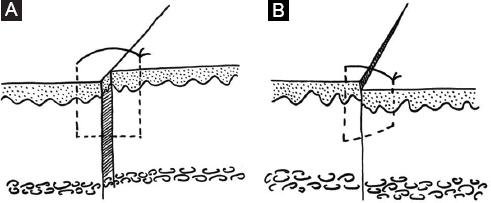

Exact conjunction of wound edges needs to be controlled in two planes, because vertical, as well as horizontal shift of the wound edges, may occur (Fig. 1). The vertical shift can appear by passing the needle through the wound edges at a different depth on each side, which causes a predisposition for hypertrophic scarring, leading to impaired wound healing. The horizontal shift occurs when the suture does not traverse the wound longitudinal axis precisely perpendicular and usually leads to the discrepancy of skin adherence, which is referred to as a “dog ear”1. This defect is highly undesirable as it is usually treated with the extension of the wound or use of excessive suturing material in the new three-bite technique described by Jaber2.

Figure 1 Incorrect conjunction of wound edges may appear in two planes. A: horizontal shift when the needle passes the wound edges obliquely. B: vertical shift when the needle passes through the wound edges at a different depth on each side.

Excessive suture tension may lead to avascular necrosis of the wound edges, which is at all times unwanted for obvious reasons. By combining different suture techniques and applying a certain amount of tension to the thread, we can achieve either an inversion or an eversion of the wound edges (Fig. 2). Inverted wound edges are considered highly undesirable as only the dead keratinized cells of the skin surface adhere to each other on both sides of the upper portion of the wound. Nevertheless, these cells are incapable of contributing to proper wound healing. On the other hand, wound edges eversion is by some authors considered recommendable3,4. By everting the wound edges, we aim to compensate for the natural tendency of the scar to contract, hence effectively preventing subsequential depression of the scar1,5. Kappel et al. tested this hypothesis, nevertheless, they could not prove any additional positive effect by forming everted wound edges6. On the other hand, a study by Wang et al. showed a small but statistically significant cosmetic improvement by using eversion4.

Practical guide

We can use both our hands and a pair of surgical forceps to manipulate the needle when preparing to grasp it with a needle driver. Manipulation of the needle with forceps (not touching the needle with our hands) is more demanding; however, once mastered, the manipulation is much safer and less time-consuming1.

The needle should be grasped by the very tips of the needle driver to achieve the most precision. We aim to grasp the needle at a point situated between 1/2–1/3 and 2/3–3/4 of its length. Grasping the needle closer to the tip than 1/3 of the needle length hinders the proper passing of the needle through the tissue. Conversely, attempting to pass the needle through the tissue while grasping it closer than 1/4 of the needle length away from the needle end increases the risk of bending or breaking the needle altogether1,7. The needle holder should also always be locked at first tooth only to avoid the same risks1.

When passing the needle through the tissue, it is advisable to limit the upper limb movement to pronation and supination of the forearm, setting out with a pronated forearm and finishing the suture with the forearm fully supinated. It is desirable to grasp the needle perpendicular to the long axis of the needle driver3. Some surgeons prefer to suture using their wrist; it is then necessary to grasp the needle at a 15–30° angle to the long axis of the needle driver so that it follows the natural range of motion of the surgeons wrist8. The skin needs to be penetrated at precisely 90° angle to prevent any unwanted tissue inversion (Fig. 3)7,9.

Figure 3 A: The skin needs to be penetrated at precisely 90° angle. B: to prevent any unwanted tissue inversion.

The ideal manner of passing the needle through both wound edges is a two-step process; however, if we have a needle with a diameter large enough, it is possible to proceed by passing through both wound edges in one take. If we are unsure about the size of the needle diameter, it is advisable to proceed in the two-step manner, ideally never letting go of the needle by both the needle driver and the forceps at the same time, to avoid losing the needle in soft tissues. We should never pull the needle out of the tissue using only the forceps as it is then impossible to control the rotatory trajectory of the curved needle. This leads to the straightened course of extraction and traumatization of the frail wound edges. We should never grasp the suture thread by any surgical instruments, as this leads to significant damage to the thread and impairment of the tensile strength of the suture3.

For economic reasons, the knot should be tied using the needle driver, which allows us to save the length of the thread. The needle driver should be positioned close to the wound, wrapping the suture thread twice around in a clockwise manner. The following two knots need to be tied by wrapping the thread around only once. This knot configuration has proved to be the strongest among other conventional suture knotting techniques10. The knot needs to lie straight (not twisted, which is the initial outcome) on the wound, which we achieve by rotating the threads to the opposite sides (each in the opposite direction)1. If we wrap the thread around the needle holder in an anti-clockwise manner, we obtain a granny knot, which is considered less secure. Nevertheless, papers that had found the square knot and granny knot to have the same mechanical performance have been published as well11. Should we not straighten the knots, we would get a slip (sliding) knot, which can be of value when tissue approximation under tension is desirable. Pay attention to the fact that the slip knot needs to be secured by a surgical knot; otherwise it can loosen easily under tension12.

We can apply the slip knot when distant tissue approximation is necessary; it is then compulsory to add more knots on top of the tightened slip knot to ensure it will not get loose1. A minimum of three knots is necessary8. Some surgeons emphasize tying the knot by swirling the needle driver around the stationary thread, rather than wrapping the thread around the needle driver. This technique diminishes the risk of accidentally pulling on the free end of the thread and pulling it out of the tissue altogether while being faster and more elegant1.

The improper handling of the tissue by itself can damage it. Therefore, we use surgical forceps instead of anatomical forceps, which require less force applied for a safe, yet comparably firm grasp of the tissue1. Using the skin hook or working with the tip of closed forceps is also an adequate alternative3.

Complications

A knot should only be as tight as to approximate the wound edges so that they are in contact with each other. It is imperative to take into account the subsequent tissue edema, which, in case of overly tight sutures, leads to compromised blood flow, accompanied by ischemic necrosis and a ladder-like appearance of the scar13. To prevent this complication, deep tissue suture needs to be well performed or the skin needs to be freed by accessory cuts14. Above described ischemic necrosis is also a risk factor for a wound infection15.

The suture tension can be divided into two components: intrinsic and extrinsic16. The extrinsic component is based on the strength applied to tightening of the suture, and is primarily influenced by the size of the gap between the wound edges, as well as by the relation of the incision axis to the normal skin tension lines. We can regulate both of these factors by undermining the wound edges17, adding an auxiliary incision, or by creating a favorable shape of the excision18. Special attention needs to be given to wounds traversing joints, as these are constantly strained due to the movements, resulting in traumatization, microscopic hemorrhages, subclinical inflammation and, eventually, overly fibrous and thickened scar19. It has been proved that the incidence of scars with ladder-like appearance rises when non-absorbable sutures are left in place for longer than seven days16.

Intrinsic component is based on the tissue compression due to the edema beneath the suture. This intrinsic component becomes even more important should we apply the sutures too far from the wound edges, resulting in the need to compress a larger amount of tissue together16. Should we ever succeed to eliminate all of the tension in the epidermal part of the wound, applying only skin plasters (e.g. Steri-Strip TM) is also an adequate wound treatment1. The resulting wound tension is based mostly on correctly performed suture of the hypodermis20.

Several studies have been conducted to compare the outcome of conventional manual suturing technique versus skin stapler application. The results have proved both means of treatment to be equal21 or slightly in favor of manual suturing22,23.

Even though surgical suturing seems as a simple and basic technique considerable amount of expertise is needed to achieve a perfect stitch. This review is presented in a hope that it will make surgical suturing clearer and simpler for junior surgeons and medical students.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)