Introduction

The new infectious disease caused by SARS CoV-2 coronavirus dieses-2019 (COVID-19) has spread rapidly and poses a challenge to the different healthcare systems worldwide. Daily reports from the World Health Organization (WHO) show an exponential growth in the numbers of infected persons and a large number of fatalities1.

Healthcare personnel is exposed to contagion1. Among care providers with the highest risk of infection are otolaryngologists (ENT), head and neck surgeons, and maxillofacial specialists2-6. Many scientific societies have issued guidelines and recommendations to decrease the risk of contagion7-11. Furthermore, an increasing number of publications warn about the risk of certain surgical procedures and advice regarding alternative options to minimize the possibility of infection for the healthcare team2,5,12-17.

In the head and neck area, there has been strong advice to avoid all elective procedures7-11,18. However, the chance of contagion remains, since urgent disorders still present a potentially dangerous scenario. The main goal of the present paper is to issue a document with practical recommendations for the management of emergencies in the head and neck region, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

We performed a non-systematic literature search of publications and guidelines by the main scientific societies regarding the management of surgical emergencies of the head and neck, maxillofacial surgery and otolaryngology in the context of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. We also reviewed the published literature concerning the usual management of the mentioned disorders, to adapt treatments to the current context, and to offer a safe alternative for patients and the healthcare personnel. Finally, a brief summary of how these recommendations were adapted to our socioeconomic background and available health resources, was made.

General recommendations for the management of emergencies

Do not take urgent action if the necessary protective elements are not available. Protection of the healthcare personnel should be a priority. When this recommendation is not followed, both physicians and patients are endangered19,20

However, it is mandatory to remark that the best protection for health personnel is to avoid contact of fluids with the airway. Never touch the face, nose and eyes with your hands. Hand washing is crucial

Communication between team members should be frequent and seamless. Careful selection of patients who will undergo surgery should be made with a multidisciplinary approach12,21

Whenever possible, a test to detect COVID-19 should be performed preoperatively on all patients. Knowledge regarding the patient's status will allow to adequately protect healthcare personnel and implement appropriate epidemiologic measures, and also to decrease healthcare costs related to the use of personal protective equipment (PPE)22

All patients with urgent conditions that have not been tested should be considered as COVID-19 positive8. Viral load in the mucosa of the upper aerodigestive tract is high; therefore, its surgical exam entails an elevated risk of transmission. In the absence of a preoperative SARS CoV-2 test, precautions should be adopted as if the patient were positive13,23. The AOCMF (Craniomaxillofacial) Group of the AO Foundation suggests obtaining at least two negative COVID-19 tests, separated by a minimum period of 24 h, given the possibility of false negative results8. Nevertheless, this policy is not applicable in most emergencies

If a tomographic exam is required for assessment, an additional chest computed tomography (CT) is advisable, to evaluate signs consistent with a respiratory infection15,24

PPE should be maximized, due to the high risk of aerosolization entailed in head and neck procedures. Consensus regarding PPE in procedures with a risk of aerosolization has been reached between most Otolaryngology, Head and Neck, and Maxillofacial Societies. Full PPE should consist of: face mask, goggles, N95 mask, FPP2, FPP3 or PAPRs (Powered Air-Purifying Respirators) (or surgical masks with an integrated visor), gloves (preferably double gloves), and blood-repelling gown, plus head cover and shoe covers whenever possible7,8,9,18,25. It is relevant to remember that the withdrawal of the PPE results a key point and has been described the risk of contamination and contagion notably increases during this step

One thing which is important to clarify is that the use of masks with valves only protects the person who uses them (entry of the virus). Those colleagues who are close to them are not protected because the particles of the virus are released while the person is exhaling

The operating room (OR) should be prepared for patients who have tested positive for COVID-19 and should have a negative pressure system26. Importantly, the OR should not receive positive pressure during the procedure to avoid spreading the SARS-CoV-2. After operating a suspicious or positive patient, a waiting period of at least 2 h is required before positive pressure can be restarted in the OR26

Surgical techniques should be adapted to reduce exposure risks; insufflation with carbon dioxide (CO2) should be avoided, as well as power-driven devices such as drills or electrocautery, which can generate aerosols. Surgical procedures should involve the fewest possible members of the team, and a senior surgeon should be the most experienced member. During patient intubation and extubation, the most experienced anesthesiologist and his/her assistant should be present in the OR21

All personnel should be trained in gowning and ungowning techniques and use of PPE to avoid auto-infection resulting from inadequate PPE removal21,27. At our institution, we have implemented instructional videos, simulation programs and hands-on workshops to train all team members in these maneuvers, and train promoters who can convey their learning to others

When available, telemedicine is a useful resource for the care, follow-up and support of a selected group of patients28

Restructuring of medical residency programs and training programs is suggested, according to the human resources available. The main goals are optimizing the well-being of the medical team, complying with social distance recommendations and ensuring adequate patient care29. We also advise to discontinue pre-graduate educational activities and scheduled rotations involving patient care.

Recommendations for specific management during emergency situations

RESPIRATORY FAILURE

A patient presenting with respiratory failure represents a medical emergency and is always a demanding situation for the medical team30,31.

The recommendations are:

1- The necessary equipment to manage a difficult airway should be available, as well as a trained medical personnel team32

2- The senior physician should be promptly involved, to avoid delays in decision making32

3- For cases requiring the participation of several team members, the discussion regarding management should be held at a prudent distance from the patient, to decrease the risk of contagion, whenever possible32

4- High flow cannulas and other non-invasive ventilation devices should be avoided, since they promote aerosolization. If oxygen is required, low-flow oxygen may be administered through a nasal cannula and it is recommended that the patient wear a face mask17

5- Any type of intubation is preferable to an emergency tracheostomy13

-

6- When intubation is required, recommendations are the following:14,17,33

The most experienced team member should perform the intubation

Videolaryngoscopy should be used to maximize procedure success

Rapid sequence intubation should be performed.

Prior to instrumenting the airway, intravenous lidocaine should be administered to decrease the cough reflex

Once the endotracheal tube (ETT) is in place, ventilation should begin only after the balloon or cuff has been inflated.

CANNOT INTUBATE, CANNOT OXYGENATE SITUATIONS

An emergency front of neck airway (eFONA) should be performed. When the cricothyroid membrane is palpable cricothyroidotomy is recommended, and if that were not the case, tracheostomy is indicated. A Frova intubation introducer and a scalpel should be preferably used, with a scalpel-bougie technique. Contrary to usual practice, further attempts to deliver oxygen from above should not occur during the performance of eFONA, to avoid aerosolization of virus-containing fluids when the trachea is punctured10,30,31.

TRACHEOSTOMY IN A VENTILATED PATIENT

The procedure should be performed by the better-trained and experienced personnel14,34.

Expose the area where the tracheal window will be opened

Do not remove the ETT, but rather introduce it up to the limit with the carina

With the end of the ETT located distal to the site of incision, ensure the cuff is properly inflated

Following pre-oxygenation, confirm that the patient is in apnea and without respiratory movements

Perform tracheal window

Deflate the ETT cuff and withdraw it until it is located proximal to the site of the window

Place the tracheostomy cannula, which should be non-fenestrated and with a cuff

Inflate the cuff and connect it to the ventilation system

Restart ventilation

Secure the ETT with sutures and fastening straps.

Of note, some authors have recognized percutaneous tracheostomy as a procedure with higher risk of aerosolization compared to conventional tracheostomy14. However, at present this subject remains controversial.

If a patient were to undergo tracheostomy due to prolonged intubation, the procedure should be delayed as much as possible. Most patients, who can undergo extubation, will do so after 5-10 days. In addition, the viral load decreases progressively34. Hence, the recommendation is to perform tracheostomy after day 21 post intubation35.

Epistaxis

The goal of the following recommendations is to avoid procedures that increase the risks for healthcare personnel, and to manage patients with epistaxis safely, preferably with ambulatory care6,36.

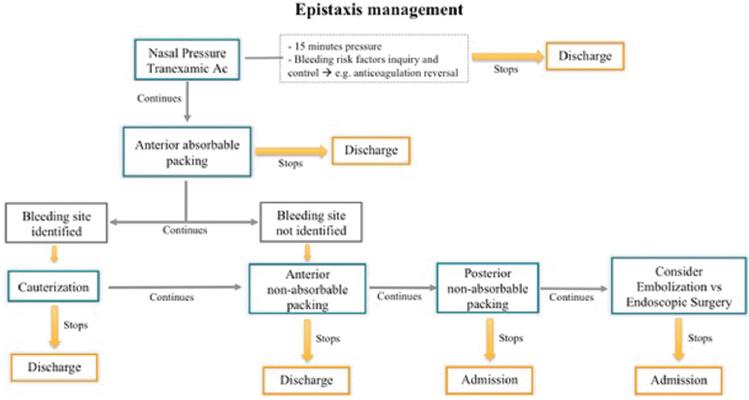

The recommendations are (Fig. 1):

Figure 1 Summary of epistaxis management. Notice that surgical management should be considered as the last resort.

Begin nasal compression and continue for 15 min, while patient is enquired about risk factors and such factors are addressed. In the absence of contraindications, administer tranexamic acid36-38

If bleeding persists, nasal packing with absorbable material is recommended, to decrease the risk of contagion during packing removal. Examples of such materials are: Spongostan®, Nasopore®, Surgiflo®, etc.38

In case of persistent bleeding, and if the bleeding vessel can be identified during rhinoscopy, cauterization with silver nitrate is advised36,38

When bleeding cannot be controlled, anterior nasal packing with non-absorbable material is recommended. An inflatable device, such as Rapid Rhino® is preferred, to save time and avoid extensive manipulation of the nasal mucosa38,39

5- If bleeding still persists or if posterior epistaxis is suspected, a posterior packing should be performed, preferably using inflatable, double balloon devices (e.g., Rapid Rhino®) to save time and avoid extensive manipulation of the nasal mucosa36,38,39

Endoscopic surgery and nasal embolization are used as last resources40,41

All patients whose bleeding has been controlled following steps 1, 2, 3, and 4 can be managed as outpatients, with telephone follow-up and telemedicine resources. An ambulatory follow-up after 24-48 h is advised. The patients who require posterior packing, embolization or surgery should be admitted for appropriate monitoring36,38.

Maxillofacial trauma

Emergency surgery in the maxillofacial area should be limited to the surgical management of facial fractures that require open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF).

1- General recommendations for facial fractures treatment are: (a) perform incisions with a scalpel, (b) avoid the use of electrocautery, (c) prefer the use of low-power bipolar cautery, (d) when drilling is required, use a low speed and avoid flushing, (e) use self-drilling screws, (f) if osteotomies are required, use osteotomes instead of high-speed saws or drills, (g) the use of absorbable sutures is recommended, as well as a device for continuous suction of saliva2,15

-

2- Mandibular fractures:

Consider closed reduction with intermaxillary fixation (IMF), securing the occlusal relationships using self-drilling screws and elastics

For fractures requiring ORIF, consider intra-oral placement of the IMF screws and elastics for control of the occlusion, seal the oral cavity with a self-adhesive patch and perform reduction and fixation using extraoral approaches.

-

3- Midface fractures:

Consider a closed reduction only if the fracture remains stable after reduction

Use Carroll-Girard screws for reduction of the zygoma (avoiding an intra-oral incision) if two fixation points are enough to stabilize the fracture (frontozygomatic and infraorbital rim fixation)

Most zygomatic arch fractures do not require surgical treatment

We suggest not operating orbital fractures in an emergency setting, except when there is content entrapment, hematoma with compromised vision, orbital apex syndrome, or an upper orbital fissure syndrome

It is best to postpone surgeries for nasal fractures, except for the drainage of septal hematomas.

-

5- Facial soft tissues16:

(a) if there is damage to critical structures, such as the facial nerve, other cranial nerves, eyelids, lacrimal apparatus or the nose, the patient should be examined by a craniomaxillofacial surgeon for early resolution, (b) lesions to the lacrimal apparatus or eyelids require assessment of the status of the eye globe, (c) most oral lacerations do not require closure.

Foreign body in the upper aerodigestive tract

Accidental swallowing of foreign bodies is a medical emergency, since they may damage the mucosa and cause severe complications with high morbidity and mortality.42

Endoscopic exams offer a diagnostic and therapeutic tool, but entail a high risk of contagion9,18,42. The recommendations below address the appropriate selection of patients, to avoid unnecessary exposure in cases in which the suspicion of foreign body is low.

Obtain a careful history, to assess the actual risk of the patient having swallowed a foreign body: the nature of the object, its composition (radiopaque or radiolucent) and estimate the potential damage to the aerodigestive tract mucosa (e.g., a chicken bone, fish bone, batteries)42

Look carefully for key signs and symptoms: drooling, stridor, dysphonia, crepitation, neck edema, emphysema, and difficulty breathing42,43

If the history is inconsistent and the patient has no symptoms, the recommendation is to obtain an X-ray of the neck's soft tissues (lateral view) or tomographic exam. In the absence of consistent radiologic or tomographic signs, (emphysema, neck edema, air in the cervical esophagus, or presence of a foreign body), the recommendation is not to perform nasolaryngoscopy, discharge the patient with clear instructions to watch for abnormal symptoms, and follow him/her with telemedicine resources and ambulatory control43

If the history is consistent with ingestion of a foreign body, the patient has symptoms, and/or radiological signs are suggestive, a nasolaryngoscopy is recommended43

-

When nasolaryngoscopy is necessary13,42-44:

It should be performed by the most experienced personnel

Videoendoscopy is the preferable method, since it allows to maintain a greater distance from the patient

Local anesthetic and decongestive agents should be applied before the procedure, preferably through pledgets, to decrease sneezing and cough reflexes.45

Deep neck infections (DNI)

DNI comprise various disorders that can potentially lead to severe complications. Early diagnosis is essential, and usual management comprises strict airway control, antibiotic therapy, and surgical drainage. Open drainage entails a risky situation for healthcare providers and may result in a prolonged hospital admission.

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic forces us to find reasonable alternatives, with less aggressive treatments but without compromising patient safety. Many DNI will probably be managed as usual, implementing the safety measures known to all healthcare personnel. However, a selected group of patients may be treated differently, without endangering their health and with less risk to the medical team.

The recommendations are (Fig. 2):

Figure 2 Summary of neck abscess surgical management. Notice that mucosal approach should be avoided if possible. Algorithm adapted from Biron et al. Surgical vs ultrasound-guided drainage of deep neck space abscesses: a randomized controlled trial: surgical vs ultrasound drainage. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;42:18.

Patients with DNI and a compromised airway should be managed with antibiotics and open drainage46-48

In open drainages, it is advisable to avoid transmucosal approaches. If such approaches are necessary, a scalpel should be used23

For patients without a compromised airway, with a well-defined and unilocular abscess, an image-guided, percutaneous drainage is advised. Such approach requires a shorter admission time and has proven to be a safe and effective option in these patients47-50

During percutaneous drainage, a catheter may be left in place until abscess resolution. A central line or 7 Fr. an equivalent catheter may be used46,47,50. Pigtail type drainages are not recommended for abscesses smaller than 1.5 cm in size50

In abscesses secondary to a dental infection, the definitive resolution of the original dental problem may be delayed, and managed on an ambulatory basis47,48,51.

Peritonsillar abscess (PTA)

Unless adequately treated, a PTA may progress and compromise the airway, extend to the deep tissues of the neck and be life threatening52. The goal of the recommendations listed below is to decrease exposure during patient evaluation and treatment, as well as to reduce hospitalization rates.

Oral exams should be avoided whenever possible. If needed, we suggest that patients rinse their mouth and gargle several times with mouthwash containing topical povidone-iodine53

When imaging methods are required, tomography is suggested54. Transoral ultrasound should be avoided55

Many PTA may be treated safely only with medical treatment, without needle aspiration or incision and drainage. Medical treatment should include antibiotics, pain relievers, and a short course of low dose steroids (care must be taken if COVID-19 is suspected)55-58. They do require a strict clinical follow-up to detect patients who might require surgical treatment52,53

-

Surgical drainage is recommended in cases of52-54:

If surgical drainage is required, we suggest performing needle aspiration rather than incision and drainage59

-

Hospital admission is advised in patients with:

Compromised airway

Sepsis

Diabetes or other conditions with a compromised immune system

Oral intolerance: in this group, initial intravenous treatment in the emergency room is recommended. If no improvement occurs after 3-4 h of observation, hospital admission is advised53,60. By contrast, if patients start tolerating oral intake and show clinical improvement, ambulatory management can be implemented.

Patients without the mentioned conditions and who tolerate oral intake (initially or following medical treatment) should be followed with ambulatory management, even if they have previously required surgical drainage53,56,60.

Unique steps based on our medical system, culture, resource and priorities

Argentina reported the first imported case on March 3, 2020. Early on, learning about the experience with the disease in Asia and Europe, our government closed the country's borders and imposed a lockdown with severe restrictions to circulation of people (March 20), which allowed better preparation of public and private healthcare resources.

Ninety days after implementing these measures, the healthcare system is burdened, but not overloaded (as of June 15, 32,000 cases have been reported and 850 people have died).

Although at the beginning, like in the rest of the world, only emergencies and oncologic cases that could not be delayed received medical care, today many of the healthcare institutions are beginning to accept elective surgery patients, at 30 % of their capacity.

Our institution is a 750-bed private university hospital. It is considered one of the best medical institutions of Argentina; however, its financial resources are limited.

Like other healthcare centers of Argentina, we have had to adapt safety measures and recommendations to our local reality.

PPE

Initially, there were many problems with the supply of N95 masks. Following the guidelines accepted by the manufacturers themselves, we use them for 15 days (provided that they are used for less than 8 h a day), and they are sterilized with hydrogen peroxide, which prolongs their life span and to preserve equipment. To avoid soiling them with fluids, a regular surgical mask is placed on top of the N95.

Blood-repellent gowns in good condition are also re-sterilized.

COVID test

Initially, we did not have the possibility of performing large scale COVID PCR tests, therefore all patients were considered suspicious cases and maximum protection was implemented without exceptions. Currently, the Institution has PCR tests with results available in 4 h. When urgent cases allow time for performing the test, only one swab is obtained.

Patients who have been vaccinated61

Systemic respiratory vaccines generally provide limited protection against viral replication and shedding within the airway, as this requires a local mucosal secretory IgA response. Preclinical studies of adenovirus and mRNA candidate vaccines demonstrated persistent virus in nasal swabs despite preventing COVID-19. This suggests that systemically vaccinated patients, while asymptomatic, may still become infected and transmit live virus from the upper airway.

Until further knowledge is acquired regarding mucosal immunity following systemic vaccination, otolaryngology and head and neck surgeons should maintain precautions against viral transmission to protect the proportion of persistently vulnerable patients who exhibit subtotal vaccine efficacy or waning immunity or who defer vaccination.

ORs

Our Hospital does not have ORs with negative pressure; hence, we have assigned specific ORs for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID, and in them the air conditioning equipment has been disabled to avoid positive pressure. Furthermore, the use of patient warming devices is avoided, since they increase ambient temperature and may result in the fogging of protective equipment.

Telemedicine

Although the Hospital has its own telemedicine system, many patients are not able to use it. The main limiting factors are lack of access to hardware, low connectivity, lack of education, advanced age, or other socio-economic reasons. These hurdles have been partially overcome with the use of instant messaging apps or telephone calls, and for cases in which effective communication has been achieved, the resulting information is recorded in the patient's electronic medical record.

Adaptation to specific management of emergencies

In ventilated patients who require a tracheostomy, our preferred procedure is a fiberoptic bronchoscopy-guided percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy, since in our experience it offers a safer and faster option. It is performed preferably 21 days after initiating mechanical ventilation, and requires only two operators, either an anesthesiologist or intensive care physician to perform the bronchoscopy, and the surgeon. Procedures are performed at the patient's bedside in the intensive care unit. To contain costs, we do not use disposable endoscopes62.

For the management of neck abscesses, given the cost of commercial drainage sets, we prefer the use of central line catheters.

Fortunately, for all other urgent procedures we have the appropriate materials available and follow the recommendations mentioned before.

Conclusion

The SARS CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic poses a threat to the general population as well as to healthcare workers. It is paramount to adapt our practices and take all necessary precautions to decrease the risk of contagion, while offering our patients safe and effective treatments. In this paper, we have reviewed several recommendations and suggestions, which we hope will contribute to optimize the management of head and neck emergencies in the context of this pandemic.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)