Similar to other East and Central European countries, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Hungary experienced profound changes in its political and social-economic system, moving from a socialist country with a centrally planned economy to a democratic political system with market economy. The socialist ideology emphasizing the collective and common goods was challenged by the novel ideological emphasis on self-interest and autonomy. Hungarian youth, that time, was not just in a developmental transition from adolescence to young adulthood but they also had to navigate and adjust to the rapid changing society resulting in a vulnerable state of ‘double limbo’ (Fülöp 2005; Roberts et al., 2000). Today, more than 25 years after the regime change, Hungarian teenagers do not belong any more to the so called “Omega-Alpha” generation (Van Hoorn et al., 2000), they are not the last children of the old socialist system and the first adults of the new. They have already been socialized in a capitalist market economy and a democratic society without first-hand experience of the socialist era. However, most of their agents of socialization (i.e. parents, teachers) experienced the communist-socialist ideology to varying extents, so they might implicitly convey the values (i.e. community over self) and norms of the old system to the new generation. Nowadays, a ‘socialization deficit’ emerged, meaning that young people learn the adult behaviour from a generation which was socialized in a different political and economic system (Domokos & Kulcsar, 2005). Therefore, the question arises what kind of values and self-construct characterize this ‘Beta- generation’ of young Hungarians? Are they similar to the older generation raised in the socialism or has their cultural orientation shifted to that of Western youth influenced by capitalism? In the present paper we discuss the potential effect of system change on Hungarians’ identity, value system and beliefs about personhood in relation to individualism and collectivism (I-C) as a suitable theoretical framework.

Because of the four decades of ideological emphasis on the collective as opposed to the relatively novel ideological importance of individual in Hungary it could be assumed that collectivistic values survived and Hungarian citizens are less individualistic and more collectivistic compared to the citizens of those European countries that do not have such ideological past. However, previous research suggests that Hungarians have managed to catch up with individualism very fast (Domokos & Kulcsár, 2005; Fülöp, 2005; Macek et al., 1998). Moreover, although the ideology of communism emphasized collectivism and common goods, well during the socialist regime, Hungarians showed signs of individualism with a lack of strong community spirit (Hollos, 1980; Hunyady, 1996). Despite the political propaganda even cultural products (i.e. short stories) reflected increasing individualistic tendencies over the period from 1910 to 1969 (Martindale & Keeley, 1986). Additionally, Hungarian youth as a result of a relatively less strict political system after the 1956 revolution against Stalinism intended to distance itself from the official state ideology and to imitate and identify with the Western youth in attitudes (i.e. non-conformist), life style (i.e. beat music) and appearance (i.e. blue jeans, long hair) (Csapó, 1994). Similarly, Kertész et al. (1986) found more similarities than differences between the self-image of Hungarian youth living and being socialized in a socialist country and the self-image of American youth raised in a prototypically individualistic society. Hankiss and his colleagues (Hankiss et al., 1983) also found great similarities between the American and Hungarian value systems; moreover, they even showed that individualistic tendencies were more expressed in the socialist Hungary compared to the USA because their collective values were also emphasized.

The collapse of the socialist regime opened the door to capitalism that legalized personal interest and even more increased individualistic tendencies among Hungarians up to the level that by the end of 1990s they even surpassed their counterparts in the West (Fülöp, 2005, 2006; House et al., 2004; Owe et al., 2013). Fülöp et al. (2002) compared Hungarian and English teachers and found that Hungarian teachers did not consider the community as important as English teachers did. Similarly to this, Hungarian teenagers did not perceive their local society as cohesive and caring, they were not interested in communities and they rather liked to be engaged in individual activities (Macek et al., 1998). Furthermore, after the system change young people in post-socialist countries had a misanthropic view of their fellow students; they rather looked out for themselves and their close friends than were willing to participate in activities that benefitted the community (Flanagan et al., 2003).

The transition has also affected value orientation. Gábor (2006) investigated the value preferences of young Hungarian people and found that individual values and self-interest were ranked much higher than community values. The value orientation of Hungarian youth was dominated by materialist values and the preference for traditional values was low.

The system change had also affected family-related thinking. Although Hungary has been characterized for its collectivistic features regarding family and small groups (i.e. strong family ties, value of family) (Fülöp 2005, 2006), a shift had been observed towards individualism (Spéder & Kamarás, 2008). While during socialism the future aspirations of youth focused on family, marriage and childrearing, by 2001 the family-oriented future plan changed to self-centred aspirations involving self-actualization, individual career opportunities and work plans instead of marriage and children (H. Sas, 2002).

Although young people embrace autonomy partly as a characteristic of their life stage (e.g. Erikson, 1998), a cohort effect may play a role as well and young Hungarian people today are more autonomous compared to the youth in the past regime. According to the World Value Survey (WVS 2010), over the last 20 years in Hungary, independence has become an increasingly important child-rearing value and young Hungarians claim more independence and agency for example in school work than their parents did (Hunyadyné & Nádasi, 2014).

The aforementioned studies drew attention to the increasing level of individualism in Hungary after the collapse of communism. Beside the system change, individualistic tendencies have been also supported by the increasing trend of globalization and post-modernization. Although globalization refers to the interchange of different world views, in reality, values of the global culture are based on individualism, free market economy, and democracy, therefore globalization has been increasing the level of individualism worldwide (Arnett, 2002). After the fall of communism, Western ideologies and products were easily attainable, and with the rapid advancement of modern technology young Hungarians could easily immerse themselves in the global and ‘Westernized’ youth culture (Fülöp, 2005).

Nowadays, Hungary is regarded as an individualistic country (House et al., 2004; Bakacsi et al., 2002), however there are essential differences between the traditionally individualistic countries without decades-long socialist influence (i.e. the USA or the UK) and those emerged in the European political regime change. High level of individualism in Hungary has been shaded by the aftermath of the communist past which eventuated numerous negative effects such as citizens’ high level of distrust in state institutions (Oross, 2013), intense money-orientation (Fülöp, 2005), a belief that individual effort is non-rewarded (Fülöp, 2005, 2007; Macek et al., 1998), a view that competition is mostly negative (Fülöp, 2002), inadequate psychological coping with situations of winning and losing (Fülöp, 2005), and a rather pessimistic and uncertain view of the future (Hideg & Nováky, 2002).

There has been very scarce research assessing I-C orientation among Hungarian youth. Ten years after the regime change Csukonyi et al. (1999) investigated I-C among Hungarian university students with the Singelis (1995) Individualism and Collectivism Scale and via a value questionnaire based on values described by Schwartz’s (1994). They identified four different groups based on the results: the Individualist, the Collectivist, the Complex (scores high both on individualism and collectivism) and the Rejecting (prefer neither individualism nor collectivism). The preference was equal towards collectivism and individualism. Since this almost 20 years-old study no further research has focused on individualism - collectivism in terms of self-concept and values among Hungarian youth.

The present research

Although several studies imply the increasing tendency of individualism among Hungarian youth, most research did not measure explicitly individualism and collectivism or applied I-C as an interpretative framework. Large-scale studies involving Hungary focused typically on adult samples and did not provide culturally embedded description of the participating countries (e.g. House et al., 2004; Owe et al., 2013). Hence, there is little knowledge on the cultural orientation of the Hungarian youth. Moreover, there has been no study that measured the ‘Beta generation’s’ value orientation, self-construal and beliefs of personhood and compared these characteristics to the value orientation, self-construal and beliefs of personhood of those who were born and socialized in the socialist system and experienced the system change in their adulthood.

The study to be presented was part of a broader research project involving 33 nations that measured identity constructs and cultural orientation (Owe et al., 2013; Becker et al., 2012; Becker et al., 2014; Vignoles et al., 2016). In the present paper, we focus on the Hungarian data and that segment of the research that aimed to (1) measure the I-C orientation in Hungary with various facets of the construct, and (2) compare the cultural orientation of young and adult Hungarians in order to identify the potential differences between the generation of the system change and the ‘Beta’ generation of young people. The original research project focused on the multinational comparison and did not analyse data of individual countries and did not provide country specific explanations. The goal of the present study was to concentrate on the Hungarian data and to reveal what they demonstrate about the current status of individualism and collectivism of two generations in a post-socialist country almost three decades after the political system change.

The main three facets of the I-C orientation construct of the multinational research project (Owe et al., 2013; Becker et al., 2012; Becker et al., 2014; Vignoles et al., 2016) were selected to assess the Hungarian participants regarding their self-construct, value system and beliefs of personhood.

Self-construct. Despite the ongoing debate on the conceptualization and multidimensionality of I-C, researchers agree that the central aspect of the construct is the relative emphasis on the self in relation to others (Hofstede, 2001). The self-approach towards culture suggests that culture shapes the way people think about themselves and their relation to others. Members of collectivistic cultures tend to view the self as interconnected with others whereas members of individualistic cultures consider the self as a unique entity independent from others (Gudykunst & Lee, 2003; Markus and Kitayama, 1991; Singelis, 1994). Although Markus and Kitayama (1991) stated that self-construal is a mediator in the culture-behaviour relationship, over time the independent-interdependent self-construals have been considered almost identical with I-C orientation and have dominated in the measurement (Owe et al., 2013).

Values. Beside the representation of the self, values form the second important dimension of the I-C orientation which has been suggested an appropriate construct to investigate the influence of societal changes over time (Owe et al., 2013). Values are expressions of the individuals’ motivational goals and serve as guiding principles for attitude formation and behaviour (Schwartz, 1992). Currently, Schwartz’s (1992) model of human values is the most well-established approach. The model describes an individual-level value structure of 10 value types. Gheorghiu et al. (2009) suggested to organize the values (except for hedonism) into two higher-order bipolar dimensions which express orientation towards individualism versus collectivism: (1) Openness to Change versus Conservation and (2) Self-enhancement versus Self-transcendence. These higher-order value dimensions converge well with Individualism (Openness to change and Self-enhancement) and Collectivism (Conservation and Self-transcendence).

Contextualism. Beside self-concepts and values, beliefs of personhood have been a less studied dimension of I-C, however, studies emphasize its growing importance (Bond et al., 2004; Owe et al., 2013). The construct of contextualism, specifically refers to the perceived importance of the context in understanding people. This includes social and relational contexts, such as family, social groups, and social positions, but also physical environments (Owe et al., 2013). There are cross-cultural differences in the way individuals use context in defining people (Shweder & Bourne, 1984; Owe et al., 2013). In understanding people, members of individualist cultures tend to provide a context-free description, whereas members of collectivistic cultures take into account the social context (Miller, 1984; Morris & Peng, 1994). Owe et al. (2013) propose contextualism as an essential facet of collectivism to measure beliefs about people.

Building on the research cited in the present paper, the goal of the present study is to investigate and compare the self-construct, value system and beliefs of personhood of two different generations of Hungarians: the older generation raised in a socialist regime and the younger ‘Beta generation’ being born already in a capitalist society. Based on the cited studies, we hypothesize that Hungarians can be characterized by individualistic tendencies. Regarding generational differences we assume that young Hungarians are more individualistic than the older generation. Given the international aspect of the original research project (including traditional Western European market economies and other post-socialist countries), we propose to interpret the results within a comparative framework.

Method

Sample

Two different datasets were obtained from a larger cross-cultural study (see Owe et al., 2013). For the first dataset, data was collected in four different Hungarian high schools in Budapest. Parental consents and permission from the principal of the schools were obtained prior to the data collection. Participants were high school students (N = 239) aged 16-20 (M=17.51, SD = .80). The sample consisted of 115 male (M age = 17.57, SD age = .73) and 123 female respondents (M age = 17.45, SD age = .86). In one case gender was not specified. The second dataset contained an adult sample with 122 individuals aged 37-75 (M = 40.02, SD = 12.17). It consisted of 71 male (M age = 41.90, SD age = 13.18) and 51 female (M age = 37.41, SD age = 10.16) respondents. Because one of the aims of the study was to explore the potential differences between generations socialized in different eras (before and after the end of the communist governance), participants of the original multination study who were under the age of 36 were removed from the sample. The age restriction indicated that participants under the given age limit were 10 years old or younger at the end of communist era in Hungary, thus they may have been less affected by the socialization process of the system.

Materials

Portrait Values. Value orientation was measured using Schwartz’s 21-item Portrait Value Questionnaire (PVQ; Schwartz et al., 2001). Four higher-order values were calculated: Self-transcendence (Universalism, Benevolence), Self-enhancement (Achievement, Power), Conservation (Conformity, Traditio, Security) and Openness to change (Self-direction, Stimulation). Based on these dimensions, we further calculated two bipolar variables: Self-focused (Self-enhancement) vs. other-focused (Self-transendence) and Independence (Openness to change) vs. Interdependence (Conservation). Responses were rated from 1 (Very much like me) to 6 (Not like me at all). Items were reversed and therefore higher scores indicate greater values. The internal consistency of the values were good/acceptable on the present sample (Openness to change: α = .76; Self-transcendence: α = .63; Conservation: α = .66; Self-enhancement: α = .75).

Contextualism (defined as a set of beliefs related to the context in understanding individuals) was measured with a 6-item scale, developed by Owe et al. (2013). Responses were rated from 1 (Completely disagree) to 6 (Completely agree). The scale included items such as “To understand a person well, it is essential to know about which social groups he/she is a member of”, or “To understand a person well, it is essential to know about his/her family”. The scale showed relatively good internal consistency on the present sample (α = .77).

Self-construal among the high school students was measured using a short version of the Gudykunst Self-construal Scale (Gudykunst, Matsumoto, Ying-Toomey and Nishida, 1996), with the inclusion of 22 items. 13 items measured independence (e.g.: “It is important for me to act as an independent person”), and 9 items measured interdependence (e.g.: “I will sacrifice my self-interest for the benefit of my group”). Responses were rated from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). Both factors showed relatively good internal reliability on the present sample (Independence: α = .72; Interdependence: α = .68).

The adult respondents completed a somewhat different version of the scale with reworded items. This way, sixteen items were included in the analysis, eight measuring independence (α = .61) and eight measuring interdependence (α = .63). This version of the scale rates responses from 1 (completely disagree) to 9 (completely agree).

Results

Means and standard deviations are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics and between subject comparisons for the young and adult sample

| Young | Adult | F | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| PVQ | Openness to change | 4.52 | 0.98 | 4.16 | 0.87 | 11.64* |

| Self-trasendence | 4.36 | 0.87 | 4.35 | 0.95 | 0.02 | |

| Self-enhancement | 4.01 | 1.01 | 3.48 | 1.04 | 21.21** | |

| Conservation | 3.3 | 0.85 | 3.88 | 0.87 | 35.44** | |

| Independence-interdependence*** | 1.22 | - | 0.28 | - | - | |

| Other focused-self focused *** | 0.35 | - | 0.87 | - | - | |

| Contextualism | 2.78 | 0.88 | 3.34 | 0.98 | 32.26** | |

| Self-construal | Independence | 6.93 | 0.9 | 6.15 | 1.01 | - |

| Interdependence | 5.69 | 1.11 | 5.37 | 0.97 | - | |

Note: *p<.05;**p<.001; *** bipolar means

Results show that when values were combined into the four higher order values, young respondents valued the dimensions in the following, descending order: Openness to change (M = 4.52, SD = .98); Self-transcendence (M = 4.36, SD = .87); Self-enhancement (M = 4.01, SD = 1.01); Conservation (M = 3.30, SD = .85). Following Owe et al. (2013) procedure to define the position each group on the two bipolar dimensions we deducted 1. from the mean of Openness to change the mean of Conservation and this constituted the score of this group on the Independence-interdependence dimension; 2. from the mean of Self-transcendence the mean of Self-enhancement was deducted and this constituted the score of this group on the Other-focused - self-focused dimension. The Independence - interdependence dimension scored 1.22 in favour of Independence, whereas the Other-focused- Self-Focused dimension scored 0.35 in favour of Other-focused values.

Adult participants had the following mean scores on the PVQ’s higher order dimensions in declining order: Self-transcendence (M = 4.35, SD = .95); Openness to change (M = 4.16, SD = .87); Conservation (M = 3.88, SD = .87); Self-enhancement (M = 3.48, SD = 1.04). On the two bipolar dimensions the score was 0.28 for the Independence - Interdependence dimension in favour of Independence and 0.87 for the Other-focused - self-focused dimension, in favour of Other-Focused values.

The mean value of Contextualism was M = 2.78, SD = .88 in the high school sample which indicates that the high school respondents rather disagreed with statements that emphasized the context-embedded understanding of people. The average score of the adult sample on the Contextualism scale was M = 3.34, SD = .98, indicating that they attributed a moderately positive importance to the context in making a person who he or she is.

Analysis of the Self-construal Scale showed that the young respondents had significantly higher scores (t(176) = 11.75, p < .001) on the Independence scale (M = 6.93, SD = .90), compared to the Interdependence scale (M = 5.69, SD = 1.11).

Adult respondents gave significantly higher average ratings (t(121) = 5.21, p < .001) for questions regarding independence (M = 6.15, SD = 1.01), compared to interdependence (M = 5.37, SD = .97) as well.

Generational differences

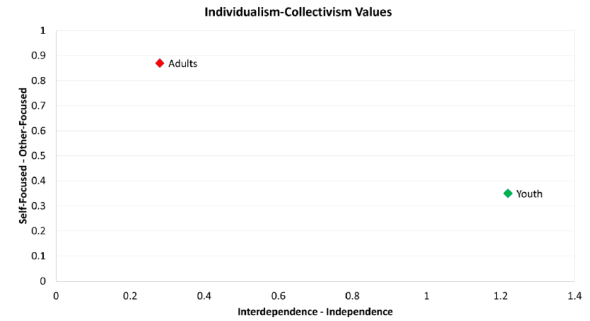

To analyse the differences between the two age groups, Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) was carried out on the PVQ’s 4 higher order dimensions. Wilks’s statistic revealed a significant effect between the two groups λ = 0.84, F(4, 348) = 16.49, p = .000. The follow-up univariate ANOVAs showed that adult respondents had significantly higher scores on the Conservation F(1, 351) = 35,44, p = .000 dimension, whereas young respondents had higher scores on the Openness to change F(1, 351) = 11.64, p = .001 and on the Self-enhancement dimensions F(1, 351) = 21.21, p = .000. Figure 1 shows that the young, high school student participants endorse other-focused values less and values of independence more than their adult counterparts.

Figure 1 Vertical axis: Self-focused-Versus Other Focused: Adults: 0.87; Students: 0.35. Horizontal Axis: Interdependence-Independence: Adults: 0.28; Students: 1.22

In addition, a separate univariate ANOVA revealed that adult respondents had significantly higher scores on the Contextualism scale, compared to young respondents F(1,371) = 32.26, p = .000. Due to the administration of different versions of the Self-construal scale, comparisons in this case could not be carried out.

Discussion

Dimensions of values, self-construals and contextualism beliefs have been theorized as elements of the same cultural syndrome of individualism-collectivism (Triandis, 1993, Owe et al., 2013). The results of the present study consistently indicate individualistic tendencies both among the participating Hungarian adults who came to age in the socialist system (1948 - 1989) and among Hungarian adolescents, the post-socialist generation being born after the political system change in 1989. Although to different extent, but both age groups proved to be self-directed and open to challenges, however they both endorsed more other-focused than self-focused values. Young people’s as well as adults’ self-construal was characterized by more independence than interdependence. Young people tended to possess a more decontextualized conception of persons, while adults attributed more weight to contextual factors i.e. social position.

Beside the prevalence of individualism in both samples, the results also show generational differences. Young Hungarian people compared to the older generation are characterized by stronger individualistic tendencies: they are more open towards changes than adults, they value self-enhancement more while values related to conservation like acceptance of tradition and security are more important for the older generation. Hungarian adults appear to be more other-focused than the younger generation. They also define their self as less independent than young people and view others more in a contextual manner as opposed to the young who tend to decontextualize more.

These differences found between two generations of Hungarians could be attributed to age differences as well as cohort differences. Previous studies widely report age-related changes in values; age correlates positively with collectivistic values such as conservatism and self-transcendence and negatively with individualistic values such as self-enhancement and openness to change (Datler, Jagodzinski, & Schmidt, 2013; Ritter & Freund, 2014; Robinson, 2013; Schwartz & Rubel, 2005). More recently, Fung et al. (2016) revealed that age- related changes in values seem to be universal independent from cultural values; both individualistic and collectivistic cultures show the same pattern. An alternative or parallel explanation can be the cohort difference. The participating adults were exposed to the socialist ideology focusing on the collective and common goods and heavily despising self-interest and autonomy. The “Beta generation” of our study however experienced just the opposite, i.e. the overwhelming manifestation of self-interest and the ignorance of public interest. Therefore the stronger individualistic tendencies among the young may also be the consequence of a dramatically changed socio-political environment of the post-socialist Hungary emphasizing the importance of individual success, competition and entrepreneurship (Fülöp, 2005).

In Owe et al. (2013) study Hungarian young people when compared to their peers in other participating countries proved to be more individualistic (i.e. traditional Western European market economies like e.g. the UK or Belgium; other post-socialist countries like e.g. Poland or Romania and a number of countries outside Europe as well). They had almost the highest value on the interdependent-independent dimension towards independence and they were among the least other-focused groups on the self-focused - other-focused dimension. Fülöp et al. (2004) also found that Hungarian high school students had a more positive attitude towards the capitalist market economy and competition in the business life than French high school students growing up in a traditional market economy. The excessive individualism of Hungarian middle managers in the GLOBE study (House et al., 2004) and our results of high school students also indicating excessive individualism in international comparison (Owe et al., 2013) pose the question of a rebound effect, namely that the socialist regime could not indoctrinate Hungarians to be collectivistic, (e.g. Hankiss et al., 1983; Kertész et al., 1986; Hunyady, 1996), and the individualism which was suppressed or kept under control surfaced itself with “double strength” after the political changes when celebrating individualism became the norm.

Although we found age-related differences in relation to openness to change, self-enhancement and conservation values, surprisingly, our study did not reveal difference in self-transcendence values. Whereas previous studies showed that self-transcendence increases with age (Datler et al., 2013; Ritter & Freund, 2014; Robinson, 2013), in our study self-transcendence values emphasizing universalism and benevolence were almost equally important for the Hungarian youth and adults. According to Inglehart (1997) economic development has a great influence on value system. Societies with increasing economic and existential security shift from materialist values toward post-materialist values emphasizing self-expression and quality of life over economic and physical security (Inglehart & Baker, 2000). The worldview and value system of those who experienced the system change in their young adulthood were shaped by an insecure environment in the turmoil of political, economic and social changes that resulted in the preference for materialist values (Inglehart, 1997). However, with age even in less affluent societies the importance of self-transcendence values is increasing. Hungarian high school students were already brought up well after socio-political changes in an economically more stable capitalist Hungary with increased financial security and abundant possibilities that open up a path towards a post-materialist value orientation. Recent Hungarian Youth Surveys indeed show that the importance of post-materialist and transcendence values are increasing and materialist value orientation is slightly decreasing in the value profile of young Hungarians (Bauer, 2002; Bauer & Szabó, 2005). Although post-materialism and self-transcendence are typically explained in different conceptual framework, there is a considerable overlap between the concepts both emphasizing non-materialist and humanistic goals like social justice, benevolence and nurture. Therefore, in case of self-transcendence, there seems to be a mixed effect of developmental and societal factors; the high prevalence of self-transcendence in the younger generation can be attributed to a gradual movement towards more post-materialistic values, whereas in the older generation who experienced a highly materialistic society after the system change in 1989 to becoming older i.e. to age-related changes.

Although the study provides an insight into how individualism and collectivism has changed in the post-socialist Hungary among two generations, it is not free from limitations. First, the study is a cross-sectional study and not a longitudinal one, which would be especially interesting in case of the adult sample. Unfortunately, historical changes cannot be predicted and be addressed in advance by a research design. In our study it is not possible to deconstruct what is age related change and what is a cohort effect which would be more directly related to socio-political changes. Moreover, the study focused on the effect of political transition, nevertheless there are still crucial changes (globalization, migration) that affect the Hungarian mindset. Future studies should apply a longitudinal design to investigate the value system and self- construct within the same person over time to gain a more thorough understanding of self, beliefs and values in a fast-changing environment.

In sum, the findings indicate that individualism is a deeply rooted cultural orientation in Hungary not influenced strongly by the principles and practices of the past political system. Individualistic tendencies might be controlled by political rules and social norms and prescriptions but the original common culture of Hungarians could not be erased even in the socialist system. The system change made it possible and encouraged to express this individualism without constraints and this is especially visible among the young participants who have never had to exert control on their individualism. In contrast to a kind of common sense belief that citizens of a post-socialist country should be more collectivistic as a result of the ideology of the former political system, the opposite is true in case of the examined Hungarian participants. When our results are placed into an international comparative framework both Hungarian adults and young people are among the most individualistic (Bakacsi et al., 2002; House et al., 2004; Owe et al., 2013).

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)