Introduction

At present, a challenge for Latin America is to maintain the growing demand for maize (Zea mays L.) through the intensive production system (Hernández et al., 2015). Usually, high doses of nitrogen fertilizer (NIFE) are applied to the soil, causing soil deterioration, with additional risk of contaminating surface and groundwater (Cárdenas-Navarro, Sánchez-Yáñez, Farías-Rodríguez, & Peña-Cabriales, 2004). Mostly, nitrogen hyperfertilization increases the production cost of maize grain, so an alternative to regulate and optimize the application of NIFE is to inoculate maize seeds with plant growth promoting bacteria (PGPB) endophytes of maize var. mexicana (teocintle). If the above is combined with the reduction of the NIFE dose at 50 %, the loss of soil fertility can be avoided (Moreno-Reséndez, García-Mendoza, Reyes-Carrillo, Vásquez-Arroyo, & Cano-Ríos, 2018; Pedraza et al., 2010).

The literature reports a wide range of PGPB genera, which are sold commercially for maize seed: Bacillus subtilis, Paenibacillus polymyxa (Gutiérrez‐Mañero, Ramos‐Solano, Mehouachi, Tadeo, & Talon, 2001), Pseudomonas putida (Kurek & Jaroszuk-Ściseł, 2003; Valdivia-Uridales, Fernández-Brondo, & Sánchez-Yáñez, 1999) and Burkholderia cepacia (Riggs, Chelius, Iniguez, Kaeppler, & Triplett, 2001). Like Azospirillum lipoferum and Azotobacter brasilense (Bashan, 1998), these genera allow the reduction of the NIFE dose and its optimization in the roots without affecting the healthy growth of the (Loredo-Osti, López-Reyes, & Espinosa-Victoria, 2004; Martínez-Viveros, Jorquera, Crowley, Gajardo, & Mora, 2010). However, these bacteria are specific and beneficial for certain varieties of maize, but not for all the varieties planted in the world; in addition, not all of them allow the reduction and optimization of the NIFE dose by up to 50 % (Massena-Reis, Ivo-Baldani, Divan-Baldani, & Dobereiner, 2000).

This study analyzed the application of PGPB endophytes of teocintle due to its close genetic relationship with domestic maize (Carcaño-Montiel, Ferrera-Cerrato, Pérez-Moreno, Molina-Galán, & Bashan, 2006; Eubanks, 2001; Galinat, 2001). Specifically, because teocintle faces environments not suitable for healthy growth, such as nutritional and water stress, and tolerance to a wide range of phytopathogenic agents. These characteristics are encoded in the genome of the teocintle, which helps it to reproduce in nature without human protection. Another biological factor that facilitates the adaptability of teocintle in complex environments is the positive interaction of this gramineous with beneficial microorganisms inside and outside its plant tissues or organs (Castellanos-Morales, Villegas, Cárdenas-Navarro, Farías-Rodríguez, & Sánchez-Yánez, 2005). Based on the above, the objective of this research was to analyze the response of the maize var. Jala to Burkholderia sp. and Klebsiella oxitogena, teocintle endophytes, when using nitrogen fertilizer such as urea at 50 % under greenhouse and soil conditions.

Materials and methods

Origin of Burkholderia sp. and Klebsiella oxitogena

The endophytic PGPB used in this study were isolated from teocintle obtained from specimens collected on the banks of Lake Cuitzeo, Michoacán, Mexico. The collected plants with soil and roots were preserved in an icebox at 15 °C for 2 h and were transported to the Environmental Microbiology Laboratory at the Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Morelia, Michoacán, Mexico. To obtain the bacteria, the roots, stem and leaves were disinfected with 10 % NaClO for 2.5 min, were washed six times with sterile drinking water, cut into 5 cm pieces, ground and suspended in 9 mL of detergent saline solution at 0.85 %; later, planted in 0.1 mL Pseudomonas cepacia azelaic acid tryptamine (PCAT) agar with the following chemical composition (g·L-1): 0.1 de MgSO4, 0.20 of azaleic acid, 0.2 of tryptamine (dissolved in 2 mL of absolute alcohol), 4 of K2HPO4, 4 of KH2PO4 and 0.02 of yeast extract; the pH of the agar was adjusted to 5.7 (Sánchez-Yáñez, 2007). Teocintle tissues or organs sown in PCAT were incubated at 28 °C for 72 h; during this time colonies of different species of Burkholderia sp. and K. oxytogenic appeared. The identification of Burkholderia sp. was carried out by morphological comparison of the colonial and microscopic with B. cepacia ATTC2541, or reference strain, according to the criteria of Bergey's Manual and the system API 50 CH (BioMérieux, France) (Holt, 1994). K. oxytogena was identified based on the criteria of the Bergey Manual (Castellanos-Morales, Villegas, Cárdenas-Navarro, Farías-Rodríguez, & Sánchez-Yánez, 2005; Holt, 1994).

Table 1 shows that the content of ammoniacal N in soil was low, so the NIFE dose was adjusted to the recommended for maize varieties grown in that area of Mexico. Maize inoculation with Burkholderia sp. and K. oxytogena was based on the fact that both bacteria synthesize acid and alkaline phosphatases that solubilize PO4 3- (phosphates) from the soil and optimize the NIFE in maize (Guerrero, 1990; Vallejo-Delgado, Ramírez-Díaz, Chuela-Bonaparte, & González-Íñiguez, 2004).

Table 1 Physical-chemical properties of soil used under greenhouse and soil conditions.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| pH (1:20) | 5.55 |

| Organic matter (%) | 2.1 |

| Texture (%) | 42.1 (clay), 54 (sand), 3.8 (silt) |

| Cation exchange capacity | |

| K (%) | 3.29 |

| Ca (%) | 32.5 |

| Mg (%) | 60.25 |

| Total organic nitrogen (kg·ha-1) | 53.4 |

| Ammonia nitrogen (ppm) | 6.5 |

| Mineral nitrogen (ppm) | 44.2 |

| Soluble phosphorus (ppm) | 20.37 |

| Moisture saturation percentage (%) | 40.7 |

| Field capacity (%) | 23.2 |

Inoculation of maize var. Jala under greenhouse conditions

For this study, a randomized block experimental design with five treatments, three controls and twenty replications was established. The treatments with a dose of 50 % urea were: maize with Burkholderia sp. 5 (B5), maize with Burkholderia sp. 9 (B9), maize with Burkholderia cepacia ATTC 25416 (BC), maize with Klebsiella oxitogena (KO) and maize with Burkholderia sp. 14 (B14); on the other hand, the controls were: non-inoculated maize with a 50 % urea dose (RC1), non-inoculated maize irrigated with water (FC) and non-inoculated maize with a 100 % urea dose (RC2). The maize seeds were disinfected with 0.2 % NaClO for 5 min, washed with sterile drinking water for 5 min, with 70 % (v/v) alcohol for 5 min and finally washed six times with sterile drinking water. Subsequently, the seeds of maize var. Jala were inoculated with 30 x 104 UFC·mL-1·seed-1 of each PGPB, and then three inoculated seeds were sown per pot in sterile sand. After germination, two plants were left per pot, and the surface was covered with sterile sawdust.

The maize plants were fed three times a week for 40 days with a mineral solution with the following chemical composition (g·L-1): 5 of NH4NO3, 2.5 of K2HPO4, 2 of KH2PO4, 1 of MgSO4, 1 of NaCl, 1 of CaCl2, traces of FeSO4 and 10 mL·L-1 of trace element solution (2.86 g·L-1 of H3BO3, 0.22 g·L-1 of ZnSO4·7H2O and 1.81 g·L-1 of MgCl2·7H2O, with pH adjusted to 6.8). In this case, the only response variable was the radical dry weight (RDW); this is because under greenhouse conditions it was possible to observe the rapid positive response of maize to PGPB with the urea dose reduced to 50 %, without having to wait until physiological maturity (Sánchez-Yáñez, 2007).

Inoculation of maize var. Jala under soil conditions

The experimental design used in this case was the same as the previous one. The sowing was carried out in a 800 m2 plot located in the facilities of the Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia “La Posta” de la Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Tarímbaro, Michoacán, Mexico. Maize seeds were disinfected as previously described, and then wetted with a 10 % (w/v) sucrose solution and inoculated with 3 x 106 UFC·mL-1·seed-1.

Maize seeds were sown under soil conditions at a depth of between 7 and 30 cm due to the type of soil (clay-sandy texture). The soil was prepared with a tractor in the usual way for the cultivation of maize var. Jala: harrow furrow, field border. The design of the experimental plots was 5 x 4 m, with a total area of 20 m2 and a separation of 1 m between plots, each one with five furrows; of these, only the central ones were used for sampling. The NIFE doses used were: 0, 140 and 280 kg·ha-1, equivalent to 0, 50 and 100 % of that recommended for maize in that area. Two applications of NIFE were made: one in the first weeding and another when filling the grain (Vallejo-Delgado et al., 2004). The response variables analyzed were the PSR (40 days after sowing) and the dry weight of the grain (DWG; 180 days after sowing) (Sánchez-Yáñez, 2007). The DWG was analyzed because under soil conditions, and under the conditions provided, it was possible to reach physiological maturity, which is when grains represent 50 % of the total weight of the aerial part of the plant, which is due to the fact that maize undergoes a remobilization and translocation of carbohydrates and other nutrients (Sánchez-Yáñez, 2007).

The experimental data were subjected to an analysis of variance and a comparison of Tukey means (P ≤ 0.01), using the statistical program Statgraphics Centurion (García-González, Farías-Rodríguez, Peña-Cabriales, & Sánchez-Yáñez, 2005).

Results and discussion

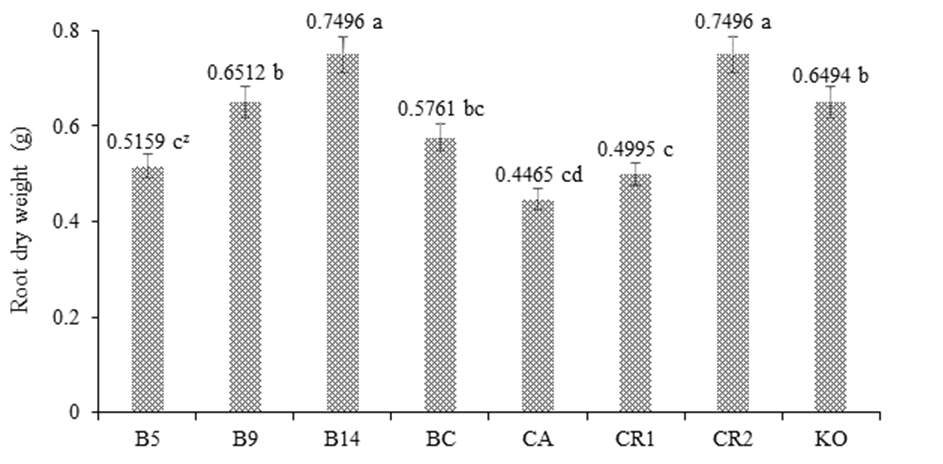

Figure 1 shows the response of maize var. Jala under greenhouse conditions, and it can be seen that treatment B14 had a positive effect by presenting a PSR value without significant statistical difference compared to the control RC2, both with values of 0.7496 g. Both B14 and RC2 were statistically different from the rest of the treatments. The positive response of maize to PGPB indicates that Burkholderia sp. and K. oxytogena, by colonizing the interior of the root primordia and normal roots, converted some organic compounds, such as amino acids of plant metabolism, into auxin-type phytohormones that promoted root multiplication, which, in turn, increased the capacity of mineral exploration and absorption, and thus optimized the dose of NIFE reduced to 50 % (Berendsen, Pieterse, & Bakker, 2012; Carcaño-Montiel et al., 2006).

Figure 1 Effect of Burkholderia sp. and Klebsiella oxitogena on the root dry weight of maize var. Jala 40 days after sowing under greenhouse conditions (n = 20). B5 = maize inoculated with Burkholderia sp. 5 and urea dose at 50 %; B9 = maize inoculated with Burkholderia sp. 9 and urea dose at 50 %; B14 = maize inoculated with Burkholderia sp. 14 and urea dose at 50 %; BC = maize inoculated with Burkholderia cepacia ATTC 25416 and urea dose at 50 %; FC = non inoculated maize and irrigated with water; RC1 = non inoculated maize and urea dose at 50 %; RC2 = non inoculated maize and urea dose at 100 %; KO = maize inoculated with Klebsiella oxitogena and urea dose at 50 %. zMeans with the same letter between bars do not differ statistically (Tukey, P ≤ 0.01).

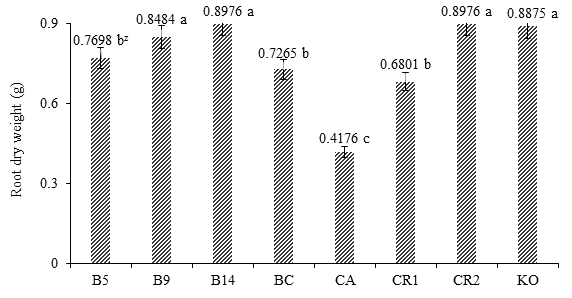

Figure 2 shows that under soil conditions, the positive response of treatment B14, with a PSR of 0.8976 g, showed no statistical difference with B9, RC2 or KO. The control FC recorded the lowest numerical value and was statistically different from the rest of the treatments. The growth of B14 was equivalent to that recorded with RC2, which is the control without inoculation.

Figure 2 Effect of Burkholderia sp. and Klebsiella oxitogena on the root dry weight of maize var. Jala 40 days after sowing under soil conditions (n = 20). B5 = maize inoculated with Burkholderia sp. 5 and urea dose at 50 %; B9 = maize inoculated with Burkholderia sp. 9 and urea dose at 50 %; B14 = maize inoculated with Burkholderia sp. 14 and urea dose at 50 %; BC = maize inoculated with Burkholderia cepacia ATTC 25416 and urea dose at 50 %; FC = non inoculated maize and irrigated with water; RC1 = non inoculated maize and urea dose at 50 %; RC2 = non inoculated maize and urea dose at 100 %; KO = maize inoculated with Klebsiella oxitogena and urea dose at 50 %. zMeans with the same letter between bars do not differ statistically (Tukey, P ≤ 0.01).

The positive response of maize suggests that the PGPB endophytes of teocintle first lived long enough after inoculation of seeds (Moreno-Reséndez et al, 2018), and then reproduced in the seed spermosphere during germination and subsequently colonized the interior of the maize root system (Velázquez, Ventura, Hernández, Aguilar, & Hernández, 1999), where PGPB were located and transformed certain amino acids and other organic compounds of the root metabolism into plant growth promoting substances (Thomas-Bauzon, Weinhard, Villecourt, & Balandreau, 1982). These substances induced the greatest proliferation and elongation of secondary roots, which in turn increased the area of exploration of the root system to improve mineral absorption and optimize urea dosage (Gómez-Luna et al., 2012; Noumavo, Agbodjato, Baba-Moussa, Adjanohoun, & Baba-Moussa, 2016).

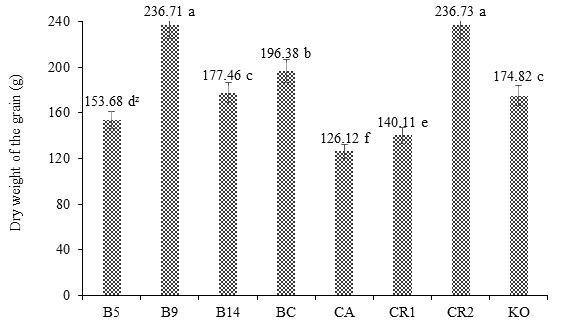

Figure 3 shows the positive response of maize var. Jala to Burkholderia sp. 9 in terms of DWG at 180 days after planting. The treatment B9 did not differ statistically from the control RC2, whose values were 236.71 and 236.73 g, respectively, but both were statistically different from the rest of the treatments.

Figure 3 Effect of Burkholderia sp. and Klebsiella oxitogena on the root dry weight of maize var. Jala 180 days after sowing under soil conditions (n = 20). B5 = maize inoculated with Burkholderia sp. 5 and urea dose at 50 %; B9 = maize inoculated with Burkholderia sp. 9 and urea dose at 50 %; B14 = maize inoculated with Burkholderia sp. 14 and urea dose at 50 %; BC = maize inoculated with Burkholderia cepacia ATTC 25416 and urea dose at 50 %; FC = non inoculated maize and irrigated with water; RC1 = non inoculated maize and urea dose at 50 %; RC2 = non inoculated maize and urea dose at 100 %; KO = maize inoculated with Klebsiella oxitogena and urea dose at 50 %. zMeans with the same letter between bars do not differ statistically (Tukey, P ≤ 0.01).

The positive response of maize to PGPB confirms that both Burkholderia sp. and K. oxitogena colonized the interior of the root system, where they transformed some amino acids derived from the heterotrophic metabolism of the roots into auxins (Ahemad & Kibret, 2014), which increased the capacity of the root exploration area, as well as the mineral absorption and the optimization of the reduced urea dose (Bevivino, Dalmastri, Tabacchioni, & Chiarini, 2000; Carcaño-Montiel et al., 2006; Parray et al., 2016). The above indicates that both bacteria, by being located inside the root system, avoided external competition from the PGPB in the rhizosphere (Ahemad & Kibret, 2014), which limits the optimization of the NIFE in maize. In addition, the specificity that exists between the genera and species of PGPB of the teocintle and the organs of maize var. Jala also contributed, given the close genetic relationship between both gramineous, because although var. Jala is a domestic plant, it has conserved genes that allowed it to interact positively with the PGPB endophytes of the teocintle (Castellanos-Morales et al., 2005; Eubanks, 2001; Hernández et al., 2015).

Conclusions

The maize var. mexicana (teocintle) is a potential source of plant growth promoting bacteria such as Burkholderia sp. and Klebsiella oxytogena, which converted organic exudates from the root of maize var. Jala into plant growth promoting substances, for improvement, optimization of the urea dose at 50 % and healthy growth; furthermore, this avoids the rapid loss of soil fertility.

text in

text in