Introduction

Floristic richness is an element that has allowed humans to satisfy their needs through domestication in agricultural production systems; the use of this resource has been transmitted from generation to generation, helping to improve aspects of food, health, and well-being of low-income populations (Hurtado et al., 2006; Gómez et al., 2016). Each social group develops a concept of the surrounding environment, observes and perceives independently from the goods and services that nature offers, and, in response, adopts particular strategies in the use and management of resources (Toledo et al., 1995). Some services that production means provides are food, ornamental species, fodder, firewood as energy material, construction materials, shelter, medicine, dyes, personal grooming, elements of mystical use, work tools, handicrafts, and fences, among others (Castañeda & Albán, 2016).

In Mexico, peasant communities have kept a strong relationship concerning the floristic resource that surrounds them, listing an average of 500 useful species that determine their social, cultural, and natural heritage, defining part of their diet, clothing, cultural, craft and medicinal activities (Lara-Vázquez et al., 2013; Balcázar-Quiñones et al., 2020). However, despite the knowledge of the communities about the use of plants, currently, due to migration and cultural variants, there is a loss of knowledge and cultural identity (Dweba & Mearns, 2011; Gálvez & Peña, 2015). Additionally, factors such as land ownership, lack of technical advice, time allocated to production, lack of water, the structure of the family production unit, and the health of producers, among others, some elements add to the loss of knowledge and abandonment of plots (Márquez-Berber et al., 2012). Given this, the interest to recover and document the cultural identity of these social groups represents an exponential trend, such studies are based on quantitative analyses that allow visualizing a hierarchical level of cultural importance based on the use of each social group (Rivas et al., 2020; Rascón et al., 2021).

The community of Atzalan is located in the northern highlands of Puebla state, México, and belongs to the municipality of Xochiapulco, currently having a total of 283 inhabitants of which 70.32 % are the indigenous population. This community is classified as an area of extreme poverty with priority attention (CONEVAL, 2020). Despite this, ancestral knowledge persists and has allowed the inhabitants to acquire resources from the natural environment for food and to cover different needs. However, in recent years there has been an increase in the migration of young people to the United States of America in search of better opportunities (CONAPO, 2020). This has caused the abandonment of the Family Production Units (UPF) and the loss of ancestral knowledge, added to this, people who still preserve their means of production, in many cases, are older adults that lack technical assistance and available labor, reducing the production yield and discouraging producers. Therefore, the present study aimed to identify the value of floristic-livestock cultural importance (plants and animals under a certain degree of domestication and with some type of use) through the characterization of agroecosystems to propose better production and management practices.

Material and Methods

The evaluated area is located in the community of Atzalan, Xochiapulco, Puebla, México (19° 53’ 49’’ N and 97° 37’ 17’’ W. 1 565 masl). The area has a semi-warm humid climate with year-round rainfall and a temperature range of 14 to 20 °C ( Franco-Mora et al., 2008 ). Ten study units (SU) were established, each one considered as an agroecosystem and UPF; this was done through a systematic sampling design. A sample size of 10 key informants was obtained for data collection. Monitoring of variables was developed every month from October 2021 to January 2022, using semi-structured interviews and field visits ( Vásquez et al., 2021 ); both were applied and conducted within the first eight days of each month. Botanical samples identified to species level were collected together (an ID was generated, which consisted of taking the first three letters of the genus and species; this was for better manipulation in the statistical analysis; for example, Allium sativum = AllSat). Likewise, for better identification, the common name indicated by the informants and photographic resources were used. The structure of each UPF was characterized (sex and age of the members of each family unit), cultural practices, yield, cost/benefit analysis, sale prices of the products, type of use of the plants-animals, and arrangement and spatial distribution of the plants. Some physical and environmental variables (slope percentage, relative humidity, and environmental temperature) were also measured using a clinometer and digital hygrometer, respectively. The cultural importance index was determined using the model proposed by Tardío & Pardo-de-Santayana (2008 ), which allows the identification of the most culturally significant plants based on the recorded, using the following equation:

CIs = Cultural importance of species e.

URui = Reports of the use of the species e.

N = Number of informants considered in the study.

It is important to mention that according to this index, an evaluation scale from 0 to 14 was used for plants and from 0 to 9 for animals, based on the number of registered uses.

A principal component analysis (PCA; Jiménez-Escobar, 2021 ; Martínez-Yoshino et al., 2021 ) was used to determine the main uses of plants and animals. These analyses were performed in the XLSTAT statistical software version 2018.7.5 (XLSTAT, 2018). Additionally, to detect possible differences in the type of use employed for the plant species recorded, a Kruskal-Wallis analysis and Tukey test were applied, both using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) (SAS, 2009) JMP IN version 8.0.2. To graphically visualize the interaction of the agroecosystem components, seen as a single production model, a cyclic Hart diagram was applied (Hart, 1985 ; Spedding, 1995 ; Machado et al., 2015 ). Similarly, to have a better description of each UPF, external economic inputs that contribute to the development of each agroecosystem were identified. Finally, based on published literature from different scientific journals, good agro-productive management practices were proposed to achieve better production results.

Results and Discussion

The evaluated agroecosystems were mostly represented by simultaneous agrosilvopastoral systems. The percentage of slope inclination recorded for each system fluctuated between 5 and 35 %, oriented in major proportion toward eastern exposure. In these agroecosystems, the average environmental temperature registered minimum and maximum values of 21.2 °C and 26.3 °C, respectively. The minimum and maximum average relative humidity were 72.6 % and 90.0 %, respectively. The UPF was represented in major percentages by older adults (42.0 %), adults (30.7 %), children (19.2 %), and young people (7.7 %). Obtained information about the schooling of participants was incomplete, primary school (70 %) and completed primary school (30 %) (Table 1). These data are consistent with those reported by Salazar-Barrientos et al., (2015); Estrada & Escobar (2020), and Arcos et al. (2021), who pointed out that the family structure is broken by sociocultural problems that force young people to migrate in search of better opportunities; generating labor shortages, loss of knowledge and abandonment of agricultural production.

Table 1 UPF structure in each study unit.

| SAF | Sex | Age | AS | NFM | Children | Youths | Adults | OA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informant A | AGS | W | 71 | UES | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Informant B | ASy | W | 41 | FES | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Informant C | AGS | M | 76 | UES | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Informant D | ASy | M | 65 | UES | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Informant E | ASy | W | 55 | FES | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Informant F | ASy | M | 68 | UES | 5 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Informant G | ASy | M | 65 | UES | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Informant H | ASy | W | 88 | UES | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Informant I | ASy | W | 73 | UES | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Informant J | ASy | W | 49 | FES | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

SAF = agroforestry system, AGS = agrosilvicultural system, ASy = Agrosilvopastoral Systems, W = Woman, M = Man, AS = Academic Studies, UES = Unfinished Elementary School, FES = Finished Elementary School, NFM = Number of family members, OA = older adults.

In all agroecosystems, the most important agricultural activity was the milpa system (maize ENT#091;white and yellowENT#093; in association with beans and squash), in which eight cultural practices were developed, most of which are covered by family and external labor. The payment per day is $130.00 (Table 2). In addition, some informants mentioned that when their economic possibilities allow them to purchase chemical fertilizers, they apply them during the cleaning and hilling period (Table 3 ).

Table 2 Day wages are employed in the cultural practices of the milpa system.

| Head of family / Key informant | CUG | SP | WR | Fertilization | Pruning | Hilling | Fold | Harvest | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FW | EW | FW | EW | FW | EW | FW | EW | FW | EW | FW | EW | FW | EW | FW | EW | |

| Informant A | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Informant B | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Informant C | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Informant D | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Informant E | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Informant F | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| Informant G | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Informant H | 0 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 3 |

| Informant I | 0 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Informant J | 4 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

CUG = clean up the ground, SP = seed planting, WR = Weed removal, FW = family workforce, EW = external workforce.

Table 3 Quantity and cost of the fertilizer applied during the development of the milpa system.

| Head of family / Key informant | Quantity (packages) | Unit price (package) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Informant A | 5 | $300.00 | $1,500.00 |

| Informant B | 4 | $450.00 | $1,800.00 |

| Informant C | 4 | $400.00 | $1,600.00 |

| Informant D | 4 | $350.00 | $1,400.00 |

| Informant E | 2 | $500.00 | $1,000.00 |

| Informant F | 4 | $500.00 | $2,000.00 |

| Informant G | 0 | $0.00 | $0.00 |

| Informant H | 8 | $500.00 | $4,000.00 |

| Informant I | 6 | $500.00 | $3,000.00 |

| Informant J | 3 | $500.00 | $1,500.00 |

The yield of maize (on an average area of 0.5 ha) averaged 244.5 kg and 33.5 kg of beans, both of which are self-consumption products; however, small portions are sometimes traded among the local inhabitants and in the local market. The selling price per kg of maize (white) varies from $7.00 to $10.00 and beans from $40.00 to $62.00 (Table 4).

Table 4 Yield and sale price of the products derived from the milpa system.

| Head of family / Key informant | CUG | SP | WR | Fertilization | Pruning | Hilling | Fold | Harvest | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FW | EW | FW | EW | FW | EW | FW | EW | FW | EW | FW | EW | FW | EW | FW | EW | |

| Informant A | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Informant B | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Informant C | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Informant D | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Informant E | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Informant F | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| Informant G | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Informant H | 0 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 3 |

| Informant I | 0 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Informant J | 4 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

*SC = self-consumption.

The informants visualize their children working outside the community. Some of them pointed out that the fields no longer produce in the same way and believe that climate variation has determined the yield of production (Table 5). Due to the increase in temperature, they have even stopped growing corn (blue and red), avocado, Chinese pomegranate, and red passion fruit, among others, since the increase in temperature has caused the appearance of pests (corn weevil and fruit fly) and decreases in yield and quality of the product. Regarding the labor used for the registered tasks, it agrees with Chamba-Morales et al. (2019) and García et al. (2019) reported the use of a greater proportion of family labor in peasant agriculture activities; however, this labor force has been reduced due to the departure of young people, who have moved to the cities in search of better opportunities.

Livestock products, as well as agricultural products, are destined for self-consumption; however, sometimes the eggs they obtain and collect are sold by the piece to local neighbors for $3.00. Chickens, which are rarely sold, have an average price of $150.00 (selling males and keeping the females for egg laying). Pigs are sold at an average price of $37.00 per kg and carcasses at $80.00 per kg. Stallions are used to fertilize the breeding sow in the agroecosystem; however, the loan of the stallion to other people consists of retributing two piglets (small pigs) to the stallion’s owner; the price of each piglet averages $800.00. The adult turkey is sold in the local market for $500.00. Small and adult ducks are sold locally at an average price of $30.00 and $250.00, respectively.

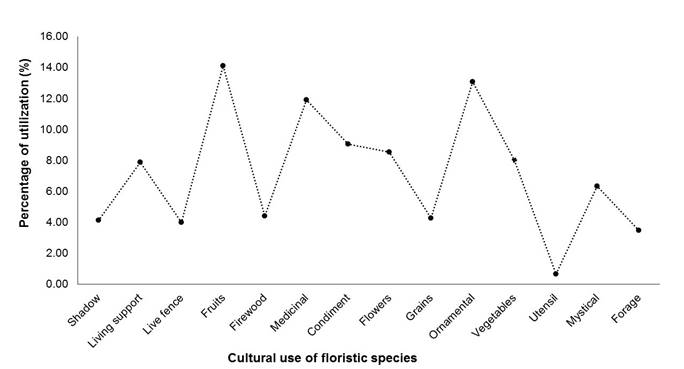

A total of 269 useful plants were recorded in the UPF, distributed in 51 families and 97 species ( Figure 1 ). Of the total species, 60 were herbaceous, 21 were arboreal, and 16 shrubby. They exhibited a total of 14 uses, with a higher percentage for fruit, ornamental and medicinal species (Figure 2). The spatial arrangement of the floristic component presented a higher percentage of random distribution, followed by uniform and semi-uniform distributions ( Figure 3 ). These results agree with what was exposed by Castañeda & Albán (2016 ) and Gómez et al. (2016 ) who determined the index of cultural value in agricultural production systems in Peru and Tabasco, Mexico, respectively; however, the dominant species for Mexico were species of the Fabaceae, Rutaceae, Lamiaceae, and Euphorbiaceae family; the latter confirms what was exposed by Garro (1986 ); Uribe-Gómez et al. (2015 ); Balcázar-Quiñones et al. (2020 ); and Camacho et al. (2021 ) who agreed that the structure, composition, and distribution of species are determined based on the geographic area. This reflects the cultural importance of the species recorded and how they have remained present despite the economic and migratory problems experienced in each of the evaluated agroecosystems.

Plants with the highest number of uses evaluated by the cultural importance index reported high values for Citrus × Aurantium (2.4), Cucurbita ficifolia (2.7), Persea Americana (4.5), Phaseolus vulgaris (3), Prunus pérsica (3.7), Ruta graveolens (2.3), Sicyos edulis (2.3), Tagetes tenuifolia (1.8) and Zea mays (4.3); the rest of evaluated plants showed lower results. In addition, livestock species with the highest importance index were chickens (2.3), turkeys (0.9), ducks (0.9), and pigs (0.9) ( Table 6 ). These results are consistent with those reported by Uribe-Gómez et al. (2015 ) and Gómez et al. (2016) which reported greater cultural importance in fruit, medicinal, and grain species. The importance of the multifunctionality represented by the tree component, which showed the greatest number of uses, is highlighted, thus corroborating the findings of Burgos et al. (2016 ); White-Olascoaga et al. (2017 ), and Vásquez et al. (2021 ) who emphasize the multifunctionality (social, economic and environmental) of this component; pointing out its dynamics according to the needs and objectives of each producer. Similarly, it agrees with reported by Ángel et al. (2017 ) which reported out the cultural value of tree species (shade, fodder, fruits, live fences, climate change mitigation, etc.) associated with agroforestry systems, indicating that the random distribution of trees is a limitation for better agroforestry management.

Table 5 Production costs and benefit-cost analysis of the milpa system.

| Head of family / Key informant | Production cost ($ /0.5 ha) | Yield (kg) | Gross Income ($) | Total | Benefit/cost ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corn | Bean | Corn | Bean | ||||

| Informant A | 4360.00 | 200 | 30 | 1700 | 1470 | 3170 | 0.727 |

| Informant B | 5050.00 | 400 | 50 | 3400 | 2450 | 5850 | 1.158 |

| Informant C | 4460.00 | 100 | 30 | 850 | 1470 | 2320 | 0.520 |

| Informant D | 4000.00 | 70 | 50 | 595 | 2450 | 3045 | 0.761 |

| Informant E | 2950.00 | 200 | 25 | 1700 | 1225 | 2925 | 0.992 |

| Informant F | 6030.00 | 300 | 40 | 2550 | 1960 | 4510 | 0.748 |

| Informant G | 1170.00 | 75 | 20 | 637.5 | 980 | 1617.5 | 1.382 |

| Informant H | 7380.00 | 250 | 40 | 2125 | 1960 | 4085 | 0.554 |

| Informant I | 8460.00 | 400 | 30 | 3400 | 1470 | 4870 | 0.576 |

| Informant J | 5140.00 | 450 | 20 | 3825 | 980 | 4805 | 0.935 |

The value of livestock importance agrees with that reported by Chablé-Pascual et al. (2015) and Monroy-Martínez et al. (2016) reported that family livestock represented in greater proportion by chickens, turkeys, and cows, are used for self-consumption purposes; however, they also represent savings for the owner since they may acquire exchange value (sale) in emergent situations (health expenses, purchase of school supplies, funeral expenses, among others). In this way, present findings are in line with Wilson (2021) who asserted that hens for meat and egg production in agroecosystems are low-yielding, as are the inputs applied (feed, medicine, labor); their production contributes to poverty alleviation, promotes food security and creates employment opportunities; they are also an asset that can be easily transformed into economic income; the latter is in agreement with the reports of Novelo et al. (2016) and Aguilar et al. (2019)who emphasize that chickens are the main livestock element due to the little management employed; they also mentioned that UPFs feed these species using grass and kitchen waste, thus avoiding costs for external inputs; they also indicated that this resource is used for self-consumption and sometimes chickens are used for festivities and customs of the region. Sutherland (2020) reported other cultural uses that are not contemplated and are rarely valued, for example, the quantification of the use of species as pets, based on the emotional comfort or service they provide: hugging a hen, living with farm animals, assigning a name, among others; likewise, this author highlights the cultural importance of pets (domestic fauna and wildlife), which were not contemplated in the present study.

Table 6 The cultural importance of the livestock species registered in the UPFs.

| Species | Present | Meat | Eggs | Mystical | Pregnancy | Sale alive | Charge | Breeding | Compost | UL | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turkeys | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 0.9 |

| Chickens | 3 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 2.3 |

| Ducks | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 0.9 |

| Pigs | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 0.9 |

| Sheep | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0.2 |

| Horses | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0.2 |

| Steers | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0.2 |

| Rabbits | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.1 |

UL = usage log, CI = cultural importance.

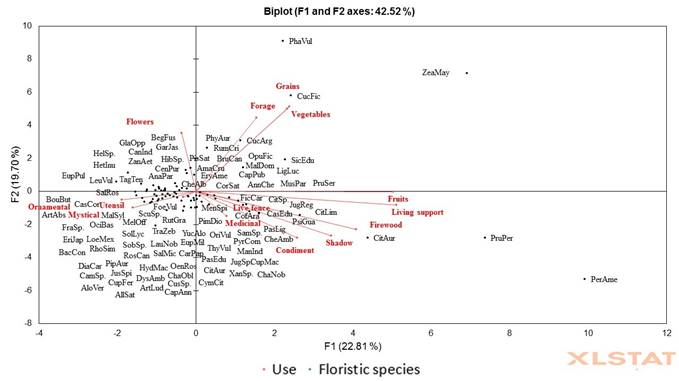

The PCA showed a proportion of accumulated variance in its first five axes (components) of 74.28 % for the floristic resource ( Table 7 ; Figure 4 ) and 98.90 % for the livestock component ( Table 8 ; Figure 5 ). The variability present among the parameters that conform and determine the type of use of plants and animals in the evaluated agroecosystems is explained. It was observed a greater correlation between vegetation and its use for living support, fruit, and firewood. The livestock resource showed a higher correlation for its use in obtaining meat, eggs, gifts, breeding, and plant fertilizer.

Table 7 Main components of the type of use used for the registered vegetation.

| Indicators | Component 1 | Component 2 | Component 3 | Component 4 | Component 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shadow | 0.35 | 0.183 | 0.011 | 0.157 | 0.019 |

| Living support | 0.769 | 0.017 | 0.007 | 0.013 | 0.007 |

| Live fence | 0.035 | 0.009 | 0.061 | 0.505 | 0.131 |

| Fruits | 0.745 | 0 | 0 | 0.026 | 0 |

| Firewood | 0.492 | 0.136 | 0.014 | 0.006 | 0.076 |

| Medicinal | 0.018 | 0.056 | 0.272 | 0.436 | 0.002 |

| Condiment | 0.197 | 0.201 | 0.029 | 0.013 | 0.171 |

| Flowers | 0.004 | 0.314 | 0.318 | 0.024 | 0.01 |

| Grains | 0.168 | 0.669 | 0.009 | 0.002 | 0.008 |

| Ornamental | 0.106 | 0.007 | 0.658 | 0.07 | 0.028 |

| Vegetables | 0.16 | 0.633 | 0 | 0.004 | 0.001 |

| Utensil | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.101 | 0.523 |

| Mystical | 0.076 | 0.025 | 0.556 | 0.062 | 0.09 |

| Forage | 0.07 | 0.507 | 0.018 | 0.004 | 0.002 |

| Importance of components | |||||

| Standard deviation | 3,194 | 2,758 | 1,955 | 1,423 | 1,069 |

| Variation ratio | 22,814 | 19,703 | 13,962 | 10,168 | 7,636 |

| Cumulative proportion | 22,814 | 42,517 | 56,478 | 66,646 | 74,282 |

Table 8 Main components of the livestock use of the registered species.

| Indicadores | Component 1 | Component 2 | Component 3 | Component 4 | Component 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | 0.855 | 0.015 | 0,011 | 0,032 | 0,075 |

| Meat | 0.905 | 0 | 0,000 | 0,003 | 0,086 |

| Eggs | 0.85 | 0 | 0,062 | 0,054 | 0,021 |

| Mystical | 0.003 | 0.011 | 0,861 | 0,056 | 0,069 |

| Pregnancy | 0.007 | 0.859 | 0,038 | 0,080 | 0,000 |

| Sale alive | 0.056 | 0.891 | 0,001 | 0,006 | 0,031 |

| Charge | 0.067 | 0.288 | 0,196 | 0,422 | 0,027 |

| Breeding | 0.939 | 0.004 | 0,007 | 0,003 | 0,015 |

| Compost | 0.631 | 0.003 | 0,153 | 0,040 | 0,169 |

| Importance of components | |||||

| Standard deviation | 4,312 | 2,072 | 1,329 | 0,695 | 0,494 |

| Variation ratio | 47,916 | 23,021 | 14,764 | 7,720 | 5,487 |

| Cumulative proportion | 47,916 | 70,937 | 85,702 | 93,421 | 98,909 |

The Kruskal-Wallis test showed significant differences in the number of species recorded for each type of use (p = 0.0004*). The Tukey analysis showed that the species used to obtain firewood, forage, condiment and live support (a plant that serves as a tutor for climbing species to develop on its stem or trunk) were similar; on the other side, the species used for live fences (tree or shrub plants used to delimit plots or production areas, or to prevent animals from moving from one place to another), ornamentals and for obtaining grains ( Table 9 ).

Table 9 Tukey’s analysis for the number of species recorded for each type of use.

| Type of use | Levels | Average | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grains | A | 5.5 | |||

| Vegetables | A | B | 4.13 | ||

| Fruits | A | B | C | 3.51 | |

| Living support | A | B | C | D | 3.21 |

| Condiment | A | B | C | D | 3.04 |

| Forage | A | B | C | D | 2.7 |

| Firewood | A | B | C | D | 2.61 |

| Flowers | B | C | D | 2.37 | |

| Medicinal | C | D | 2.09 | ||

| Mystical | B | C | D | 1.96 | |

| Ornamental | D | 1.9 | |||

| Shadow | C | D | 1.77 | ||

| Utensil | A | B | C | D | 1.66 |

| Live fence | D | 1.47 | |||

Note: Levels not connected by the same letter presented a significant statistical difference.

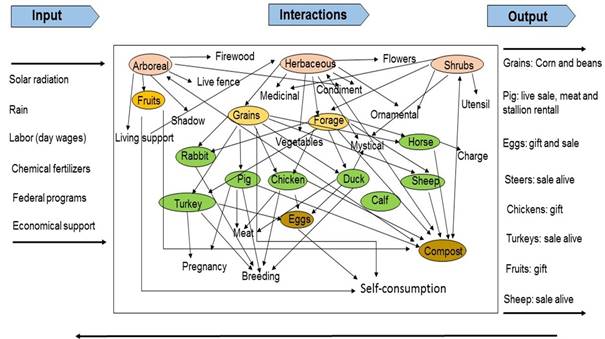

Hart’s diagram showed a cyclical and productive model based on physical, social, and ecological interactions that explain the correlation between elements that interact within the agroecosystem ( Figure 6 ).

Eight activities outside the agroecosystem were detected as significantly contributing to economic income. Informants indicated that, in times of low productive activity, they may acquire external resources by selling their labor force or by performing different productive activities. Another means of generating income is through federal or government subsidies, as well as economical support they may receive from family members working in different cities (particularly the capital of Puebla state and Mexico City). Similarly, three informants indicated that they belong to an ejido group that is in charge of a tourist center, which contributes to their economic income ( Table 10 ). These results are consistent with the findings of Uribe-Gómez et al. (2015 ); Jarquín et al. (2017), and Cuevas (2019 ) who mention how the head of household in periods of low activity sells his labor force and performs external work to acquire extra income and cover household needs; likewise, they indicated that economic support from relatives working in a different city or outside the country, along with government subsidies (senior citizens, single mothers, and student scholarships) contribute to the survival of families; however, the latter has generated paternalism in the production units, reducing the economically active population.

Table 10 External tasks that contribute financially to the UPF.

| Head of family / Key informant | SWB | SD | SL | Bricklayer | SC | TC | FS | GS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informant A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Informant B | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Informant C | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Informant D | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Informant E | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Informant F | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Informant G | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Informant H | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Informant I | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Informant J | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

SWB = Sale of wooden benches, SD = Sale of delicacies, SL = sale of labor, SC = sale of coal, TC = touristic center, FS = familiar support, GS = Government support.

Strategies for the implementation of good agro-productive management practices.

Given that the evaluated plots present a rugged orography and random floristic distribution, it is proposed to design more uniform distribution arrangements, using the contour line methodology for the tree and shrub stratum, according to Coulibaly et al. (2018); Tejeda et al. (2021) and Nabati et al. (2022), this should avoid soil loss and contribute to moisture retention, allowing a better development of the productive components.

Based on the guide proposed by Barrantes (2013) on techniques for the implementation of agroforestry systems, it is recommended to apply pruning for the formation and fruiting of tree species, in addition to avoiding or reducing the use of these plants as living support for vines (beans, squash, hedgehog, among others) that develop competition for solar radiation.

According to Rahman et al. (2018) and Kumar (2019) it is recommended to use insecticides, fungicides, and nematicides, made from organic products that avoid soil contamination and contribute to better productive development by reducing the incidence of pests.

It is suggested to increase the number of poultry (chickens, ducks, hens, and turkeys) in each agroecosystem. This is because they are the livestock product that generates the most goods and uses.

It is also recommended to establish fruit species of high commercial value (tejocote, pear, apple, blackberry, loquat, fig, walnut, and coffee, among others), which are suitable for the region’s climate and have already been approved by the state’s rural development program (Villalobos, 2019; Secretaria de Desarrollo Rural, 2021).

Conclusions

The floristic-livestock cultural importance value of the evaluated agroecosystems was determined. Families use a variety of plants and animals for multiple uses that allow them to cover their needs and determine their cultural identity. It is necessary to reflect on strategies for using and conserving resources and at the same time motivate young people to maintain the cultural knowledge that has been held since ancestral times. Local families could become actors in the development of sustainable production, bringing together knowledge and product management practices that motivate them to maintain and improve their means of production with species of high commercial value, contributing to the generation of jobs for the local population.

text in

text in