Introduction

The accelerated deforestation and fragmentation of the primary vegetation, changes in land use, forest fires, selective logging, hunting and trafficking of wild flora and fauna represent the greatest threats to the conservation of wild species (Morin 2011). Investigating how species survive in landscapes modified by man is essential to understand the adaptations that are associated with this tolerance. In addition, it is also key to identify the species that warrant immediate conservation actions (Moreno 2006; Morin 2011). Changes in the local habitat can be evaluated through species richness (Morin 2011) and the diversity of trophic guilds, which are made up of species that use the same food resource in a similar way (Dayan and Simberloff 1991). Both features provide information on the structure of communities and the way in which species use the available resources through time.

The mammals of the Order Carnivora, in particular large predators, are key species and their elimination can lead to the overpopulation of some species and the decline of others; thus, carnivores play a key role in defining the structure of communities (Gittleman et al. 2001). Some of these species are important in areas that connect large ecological reserves, because they respond differently to changes in the habitat and show a wide ecological, morphological and behavioral diversity (Gittleman 1989).

Carnivores function as ecological indicators in an area, i.e., if carnivore populations are stable, this means there is enough food for their survival. The Order includes species that serve as “umbrella species”, and contribute to the conservation of other species. However, there are also species that are at risk of conservation due to their vulnerability to impact by human activities, need for large areas with optimum habitat to survive, low reproductive rate and small population size (Gittleman et al. 2001).

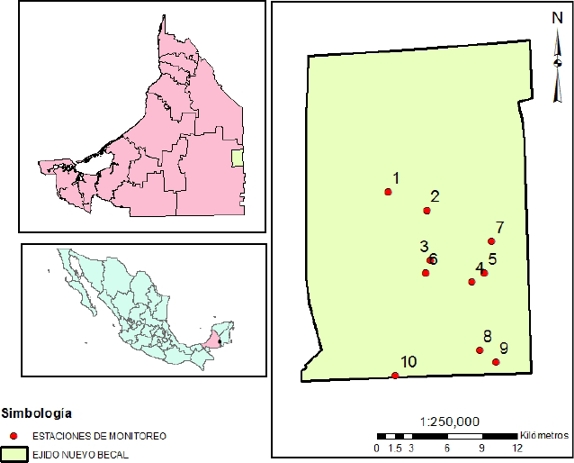

The region of Calakmul, Campeche, includes one of the main remnants of Mexico’s tropical forests, which along with the tropical forests of Chiapas, Quintana Roo and Petén in northern Guatemala and Belize, is part of one of the largest continuous forest in Mesoamerica. The area declared as the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve (RBC, for its acronym in Spanish) covers 7,231 km2 (SEMARNAT 2000). RBC includes a high diversity of mammal species, 13 of which belong to the Order Carnivora. Around RBC there are human settlements that have led to the accelerated deforestation and fragmentation of the primary vegetation, land-use changes, forest fires, selective logging, unregulated hunting, and illegal trafficking of wild flora and fauna (Secretaría de Ecología 2009). These disturbances have the potential to affect the connectivity of dispersion routes and genetic exchange of species within RBC with other conservation areas. Information on the diversity of species, including the Carnivora, is scarce in areas adjacent to RBC, but nonetheless is required in management and conservation plans of these species. One of the largest adjacent areas is ejido Nuevo Becal to the southwest of RBC, with 520 km2 (Reyna-Hurtado 2009). The area comprises large areas of forest and water bodies that are necessary for the species, particularly during the dry season, but hunting is also practiced for both subsistence and sport purposes. The objective of this study was to estimate the richness of both species and trophic guilds belonging to the Order Carnivora at Nuevo Becal.

Methods

Study area. Ejido Nuevo Becal is located in the northeast portion of RBC between coordinates (18.6920° N, -89.2511°W; 20.9450 N°, -89.6433 N°; 21.2811 N, -89.6650° W; 21.0161°N, -89.8772° W, 18.6920 °N, -89.2511 °W). The prevailing vegetation type is semi-evergreen tropical forest, with trees between 18 and 25 m high, also known as medium sub-evergreen forest (Pennington and Sarukhán 1998). Some intermediate associations are flooded forests, known locally as “lowlands” or “akalches” in Maya language, which are forests with trees between 8 and 15 m in height that are temporarily flooded because they are located in depressions on clayey soils (Reyna-Hurtado et al. 2010). Common species of plants include Brosimum alicastrum, Manilkara zapota, Pouteria campechiana, Ampelocera hottlei, Crataeva tapia, Citrullus vulgaris and Metopimu brownei (Pennington and Sarukhán 1998).

Altitude varies between 100 to 380 m. The predominant climate is warm sub-humid with summer rainfall and with less than 60 mm of precipitation in the driest month. The mean annual temperature is 25 °C; the mean annual precipitation ranges between 1,200 and 1,500 mm in the central area, and from 1,500 to 2,000 mm in the south (García-Gil 2003).

Land tenure is predominantly community-owned. Productive activities include agriculture, livestock farming, beekeeping, and coal extraction; also practiced are subsistence hunting and, to a lesser extent, hunting (Weber 2000; Escamilla et al. 2000; Reyna-Hurtado and Tanner 2007; Santos-Fita et al. 2012; Briceño-Méndez et al. 2014; Briceño-Mendez et al. 2016).

Figure 1 Location of the study area in ejido Nuevo Becal Calakmul, Campeche, Mexico. Red dots represent the monitoring stations.

Field sampling. The study was conducted from February 2014 to February 2015 and used the camera-trap method coupled with indirect records of species. Cameras were in operation for 351 days. Ten permanent sampling stations were established within the forest in sites near surface water bodies (preferentially water bodies locally known as “aguadas”), roads or trails, chosen at random. The camera-traps used were Reconyx PC800 Hyperfire Professional IRTM and PC600 Hyperfire Pro White FlashTM (Reconyx, Inc., Holmen, Wisconsin, USA). Camera-traps were placed at a height not exceeding 50 cm from ground level and separated from each other by a distance of 1.5 km to 2.5 km. An area of approximately 112 km2 was covered, based on the estimation of the minimum convex polygon formed by the external location of the traps (Reyna-Hurtado et al. 2016). The period of photographic records was set to be in operation for 24 h, and recorded one individual images every 0.2 seconds. Camera traps were reviewed once a month and those that were misfunctioning were replaced.

The photographic records of each species obtained 24 hours apart were considered as independent events. However, when in subsequent photographs different individuals of the same species were observed, each individual was regarded as an independent record. To supplement the inventory and composition of guilds, records of observations and indirect effects observed during the walks to review camera traps were also taken into account. For the analysis, only the data obtained from camera traps were used. The identification of field tracks was carried out using the identification guides of Aranda-Sánchez (2012).

Data analysis. The collection effort of through camera-traps was expressed as the number of traps multiplied by the total number of days that these were in operation (traps * day; Medellín et al. 2006; Pérez-Irineo and Santos-Moreno 2013; Cruz-Jácome et al. 2015). The success of capture, expressed as percentage, was calculated using the total number of captures between the collection effort multiplied by 100 (Pérez-Irineo and Santos-Moreno 2013). The species richness was determined as the total number of species recorded, regardless of the method by which this number was obtained. The species richness obtained by cameras traps was estimated through asymptotic models for species accumulation curves (exponential and linear) from a matrix of the presence of species. The data matrix were randomized 100 times with the program StimateS version 9.0.0 (Colwell 2013). Asymptotic models were generated in the program STATGRAPHICS centurion version 17.0.0.

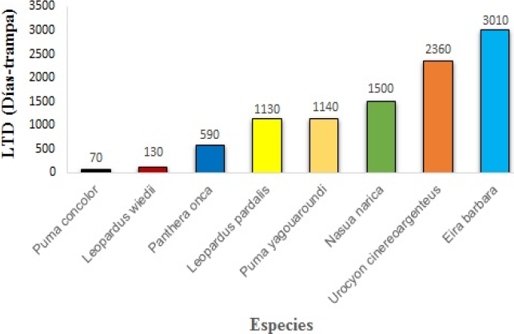

The efficiency of camera traps for recording each species was evaluated by calculating the latency to first detection (LTD). LTD was expressed as the collection effort deployed (trap-days) before obtaining the first record (Foresman and Pearson 1998; Pérez-Irineo and Santos-Moreno 2013). This allows estimating the approximate number of camera trap-days required to obtain records of the species in the study site (Foresman and Pearson 1998; Pérez-Irineo and Santos-Moreno 2013).

To determine the trophic guild, each recorded species was classified according to the most frequently consumed food category. The classification was based on the one proposed by Van Valkenburgh (1989) and Dalerum et al. (2009), and the adjustments proposed by Perez-Irineo and Santos-Moreno (2013), as well as on the description by Wilson and Mittermeier (2009). The classification was: 1) carnivores: consume mainly living terrestrial vertebrates, 2) frugivores: consume mainly fruits, 3) insectivores: consume insects and other terrestrial invertebrates, 4) scavengers: consume mainly the remains of dead animals, but may include other types of food, and 5) omnivores: show no preference to consume any specific food type (Pérez-Irineo and Santos-Moreno 2013). In addition, the richness of each guild was quantified (Pérez-Irineo and Santos-Moreno 2013; Cruz-Jácome et al. 2015). Photographs were handled and organized using the program Camera Base (version 1.6; Tobler 2014).

Results

The sampling effort was 3,510 trap-days and produced 76 independent photographic records, which correspond to a 2.6 % sucess of capture, supplemented with 15 indirect records. A total of 11 species of the Order Carnivora were recorded, included in five Families (Table 1). The asymptotic models of species accumulation indicate that the model with the best fit was linear, with an estimate of 12.66 species (model parameters a = 5. 87 and b = 0.46).

Table 1 Species richness, trophic guilds and risk category of species of the Order Carnivora according to NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010, in ejido Nuevo Becal, Calakmul, Campeche, Mexico. February 2014 to February 2015.

| Family | Species | Common Name | Recording method a | Trophic Guild b | Risk Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Felidae | Leopardus wiedii | Tigrillo, margay | F | C | Danger of Extinction |

| Felidae | Leopardus pardalis | Ocelot | F | C | Danger of Extinction |

| Felidae | Panthera onca | Jaguar | F, H | C | Danger of Extinction |

| Felidae | Puma yagouaroundi | Jaguarundi | F | C | Threatened |

| Felidae | Puma concolor | Cougar | F | C | |

| Mustelidae | Eira barbara | Cabeza de viejo | F | O | Danger of Extinction |

| Canidae | Urocyon cinereoargenteus | Gray Fox | Ob | O | |

| Procyonidae | Potos flavus | Martucha, kinkajou | Ob | F | Special protection |

| Procyonidae | Nasua narica | Badger | F | O | |

| Procyonidae | Procyon lotor | Raccoon | Obs, H | O | |

| Mephitidae | Spilogale angustifrons | Skunk | Ob | I |

a Recording method: F = camera trap, H = tracks, Ob = observation.

b Trophic guild: I = insectivore, O = omnivore, C = carnivore, F = frugivore.

Three species were recorded indirectly during walks to review camera traps: skunk (Spilogale angustifrons; n = 6), “martucha” (Potos flavus; n = 3), and raccoon (Procyon lotor; n = 6). The species photographed were “cabeza de viejo” (Eira barbara; n = 1), ocelot (Leopardus pardalis; n = 6), margay (L. wiedii; n = 25), jaguar (Panthera onca; n = 12), puma (Puma concolor; n = 22), yagouaroundi (P. yagouaroundi; n = 1), badger (Nasua narica; n = 6), and gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus; n = 3). For P. concolor and L. wiedii, the value of LTD was low (less than 140 trap-days); in contrast, U. cinereoargenteus and E. barbara attained a high LTD (greater than 2,000 trap-days; Figure 2).

Three trophic guilds were recorded for the Order Carnivora through photographs, plus one more through indirect observation. The carnivorous guild recorded the highest number of species, with five, followed by omnivorous with four and a single species for each of the insectivorous (S. angustifrons) and frugivorous (P. Flavus) guilds (Table 1). Of the 11 recorded species, six (55 %) are included in a risk category according to the Mexican Standard (SEMANART 2000): four, in danger of extinction (L. wiedii, L. pardalis, P. onca and E. barbara), one as threatened (P. yagouaroundi), and one as under special protection (P. flavus; Table 1).

Discussion and Conclusions

Assemblage. In this study, the richness of Carnivora species was 11 species. Eight were recorded in less than 3,510 trap-days, which is equivalent to rgistering 72 % of the species. This value of sampling effort was similar to the one reported in previous studies, with around 1,000 trap-days to register 40 % of the species (Kelly and Holub 2008).

This value of sampling effort differs from other previous studies where a significant percentage of the representation of the species was obtained with a lower sampling effort, as was the case of The Salt Pond Mountain forest, Virginia, with 1,000 trap-days to represent 40 % of the species (Kelly and Holub 2008); or the Peruvian Amazon forests, where 86 % of the species were represented in 2,340 trap-days (Tobler et al. 2008). In contrast, in a high tropical forest at Los Chimalapas in southeastern Mexico, a much higher sampling effort was carried out (6,000 trap-days to obtain 83 % of the species; Pérez-Irineo and Santos-Moreno 2013).

The Carnivora in ejido Nuevo Becal represent a group in a good conservation status; this is supported by the presence of predators and species that require relatively pristine environments, such as L. wiedii or P. flavus, in addition to the presence of large predators such as P. concolor and P. onca. The ejido has 33 % of the species richness of Carnivora at a country level and 64 % of the species richness in Campeche (Vargas-Contreras et al. 2014).

Generalist species such as U cinereoargenteus, P. yagouaroundi and P. lotor showed high LTD values (1,140, 2,360, and 3,010 trap-days, respectively, Figure 2) compared to other species (e. g., P. concolor and L. wiedii), so these can be considered rare in the study site. However, U cinereoargenteus is frequently observed in the roads that lead to the entrance. These generalist species prefer open habitats and are adapted to disturbed areas (Servin and Chacon 2005; Valenzuela-Galván 2005. U cinereoargenteus was observed frequently in the roads that lead to the main entrance of ejido Nuevo Becal, probably as a result of the transformation of the forest to pasture or agricultural areas. These changes may impact the richness, composition or abundance of the Carnivora in the area. For example, it has been documented that C. latrans has spread to regions where its presence had not been recorded previously, mainly in areas where the forest has been altered (Hidalgo-Mihart et al. 2013).

Eleven species were observed, and the species accumulation model indicated that there were two species missing to register. The species that could be considered as missing are Bassariscus sumichrasti and Conepatus semistriatus because these are typical of tropical forests and there are previous studies that confirm their presence in Campeche (Vargas-Contreras et al. 2014). Several species were not recorded by camera traps likely due to the location and height of placement of traps in the understory. Arboreal species such as B. sumichrasti and those of small size, such as S. angustifrons and C. semistriatus, could not be recorded due to the height at which traps were placed, favoring the recording of medium-sized and larger species. Species such as S. angustifrons, P. flavus and P. lotor were recorded only through direct sightings, indicating that camera traps did not record all the species present in the ejido. The Order Carnivora in ejido Nuevo Becal was composed of four trophic guilds, with the greatest richness corresponding to carnivores and omnivores (five and four species, respectively). Frugivores and insectivores had only a single species each (P. flavus and S. angustifrons). This diversity of guilds was similar to the one recorded in other areas where there is a higher species richness for the carnivorous and omnivorous guilds (Van Valkenburgh 1989; Zapata et al. 2008) and a lower abundance of herbivores, frugivores and insectivores (Zapata et al. 2008; Dalerum et al. 2009; Pérez-Irineo and Santos-Moreno 2013). The richness of the carnivore guild in the study site can be associated to the high diversity of prey in the area. For example, there are regions where the richness of predators is associated to areas with high levels of herbivore biomass (Van Valkenburgh 1989; Zapata et al. 2008), and this number of species depends largely on the variety of available preys (Lopez-González and Miller 2002; Silva-Pereira et al. 2011). In this regard, the assessment of prey diversity is a research topic that deserves further investigations.

It has been noted that communal areas adjacent to protected natural areas are important sites for the conservation of biodiversity, as the former maintain the connectivity between the latter (Vester et al. 2007). In addition, in certain cases communal areas may provide a greater proportion of essential resources (such as food and water) for the survival of species compared to natural protected areas. For example, it has been recently documented that ejido Nuevo Becal possesses a larger number of surface water bodies (locally called “aguadas”) where higher relative abundances of the tapir Tapirus bairdii compared to RBC. This network of aguadas forms an essential complex for the use and displacement of T. bairdii across the region (O’ Farrill et al. 2014; Sandoval- Serés et al. 2016; Reyna-Hurtado et al. 2016).

This study indicates that ejido Nuevo Bacal has a high diversity of the Carnivora, including large predators and species of other trophic guilds. More than half of these species (55%) are classified in some risk category. Given the number of surface water bodies, the connectivity with RBC, and the diversity of the Carnivora, it is recommended to focus conservation efforts toward ejido Nuevo Becal in order to maintain the large areas used for the activities of these species. Ejido Nuevo Becal is a clear example on the conservation of species outside protected areas.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)