Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Diálogos sobre educación. Temas actuales en investigación educativa

versión On-line ISSN 2007-2171

Diálogos sobre educ. Temas actuales en investig. educ. vol.8 no.15 Zapopan jul./dic. 2017

Thematic axis

Education for peace: the pedagogical proposal of the Post-Conflict Diploma Course, Medellín 2016

* Political scientist, historian, and candidate for Magister in History, School for Economical Science and the Humanities, National University of Colombia in Medellín. Teacher at the same university and researcher at the Laboratory of Social Pedagogy of the National University. rsalazarp@unal.edu.co

** Political scientist and historian, School for Economical Science and the Humanities, National University of Colombia in Medellín. Researcher at the Laboratory of Social Pedagogy of the same university. ldmarina@unal.edu.co

The Peace Process brought forward between the Colombian government and the FARC-EP guerrilla group demanded a new understanding of the internal conflict that Colombia has been living in since the second half of the last century. Within the formative options that were pronounced on this political conjuncture, it is worth mentioning the non-formal education processes that arise within communities and which reflect the thematic and pedagogical interests of their participants. The Post-Conflict Diploma Course (Medellín, 2016) is a milestone in education for peace, as it was managed as part of the Local Planning and Participatory Budgeting Program, a democratic tool that allows communities to prioritize resources for intervention in their most pressing problems. This educational scenario was built on the guidelines of the SFCP, which is based on critical and social pedagogies, and on the approach of capability and skills development of the subjects in formation.

Key words: Peace Process; Critical Pedagogy; Education for Peace; Citizen Training System for Participation (SFCP); Post-Conflict Diploma

El proceso de paz adelantado entre el gobierno colombiano y el grupo guerrillero Farc-Ep exigía una nueva comprensión del conflicto interno que vive Colombia desde la segunda mitad del siglo XX. Dentro de las apuestas formativas que se propusieron en torno a esta coyuntura política, vale destacar los procesos de educación no formal que surgen al interior de las comunidades y que recogen los intereses temáticos y pedagógicos de sus participantes. El Diplomado en Posconflicto promovido por la Alcaldía de Medellín en 2016, constituye un hito de formación para la paz, pues se gestionó como parte del programa Planeación Local y Presupuesto Participativo, herramienta democrática que permite a las comunidades intervenir en el establecimiento de prioridades en el uso de recursos públicos. Este escenario formativo se construyó a partir de los lineamientos del Sistema de Formación Ciudadana para la Participación, que se apoya en las pedagogías críticas y sociales, y en el enfoque de desarrollo de capacidades y habilidades de los sujetos en formación.

Palabras clave: Proceso de Paz; Pedagogía Crítica; Educación para la Paz; Diplomado en Posconflicto

Introduction

The political panorama that emerged after the implementation of the Dialogues for Peace between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia- People’s Army (FARC-EP) guerrillas demanded a new understanding of the armed conflict and the implications of achieving a negotiated peace with the most representative outlawed group in Colombia.

The start of the Peace Process brought on different citizen demands for an educational offer that enabled a better understanding of the armed conflict as a phenomenon to be studied. From the abundant catalog that makes up the educational menu that emerged after the Agreement for the End of the Conflict and the Construction of a Stable and Lasting Peace (Acuerdo para la terminación del conflicto y la construcción de una paz estable y duradera), worthy of mention are the bottom-up efforts; that is, those generated within the communities themselves, which made this educational offer respond to the citizens’ views, and which run counter to top-down formative programs imposed by a concrete institution. Besides allowing us to identify citizen thematic proposals to address current issues, as well as pedagogical strategies that would direct formative practices, highlighting formative processes that arise within communities also allows us to reveal citizen interests and representations regarding the conflict and its impact on Colombian society.

This paper focuses on the Post-Conflict Diploma Course (Diplomado en Posconflicto), offered by the Mayor's Office of Medellín, Colombia in 2016 and funded by the city’s Commune 10. This diploma course is a landmark in the educational proposals to consolidate a stable and lasting peace, since it arose as a pioneering experience in informal education to address the armed conflict, the social repercussions of a potential post-agreement, and the consolidation of a post-conflict.

Thus, citizens constructed the pedagogical proposal of the Post-Conflict Diploma Course based on the agreements that were being discussed in La Habana at the time. Their five discussion points became the thematic guidelines of formation: (I) Comprehensive Rural Reform, (II) Political Participation, (III) Solutions to the Problem of Illegal Drugs, (IV) Victims and Transitional Justice, and (V) Ceasing the Armed Struggle and Ending the Conflict. One last thematic guideline was added: (VI) Peace and Territory, aimed at discussing the impact of the Peace Agreement in Medellín’s reality.

Centrally, this research exercise focuses its effort on reviewing the pedagogical approach implemented in the framework of the Post-Conflict Diploma Course, which will allow us to evaluate the participants’ views on the Dialogues for Peace, as well as the relevance and effectiveness of the pedagogical proposal constructed by the community to address this important issue.

To achieve these objectives, we propose the following route of approach: (I) highlighting some key elements of the historical background to understand the negotiation process and the role of educational processes to understand — in a broader sense — the armed conflict in Colombia, (II) introducing the System for Citizen Education on Participation (SFCP, Sistema de Formación Ciudadana para la Participación) as a pedagogical reference of the educational proposal embodied in the Post-Conflict Diploma Course, (III) offering a balance of the educational experience (the Post-Conflict Diploma Course) in the light of its structuring and implementation, and (IV) outlining some conclusions, as well as the main findings and insights of this research exercise.

1 Historical background

Starting in the second half of the twentieth century, Colombia’s political panorama was marked by an ongoing armed conflict. The emergence in the 1960s of self-proclaimed Marxist-Leninist guerrilla groups fighting for a socialist political and economic project was continuously opposed by Colombian governments, who were aligned with a capitalist mode of production. Added to that, the political tension in the country was fueled by the Cold War, which “divided” the world in favor of two great international powers: the United States, which promoted the capitalist system, and the Soviet Union, the main representative of socialist ideas.

The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People’s Army (FARC-EP), the oldest guerrilla group in Colombia, formed in 1964, held that international tensions between the USA and the USSR led to a bloody persecution of advocates of communist ideas by Latin American governments, so the emergence of belligerent groups was a viable alternative to obtain the political power of the State, especially after the triumph of the Cuban Revolution in 1959 became a model to follow.

In the early 1960s, an anti-communist wave began to extend through Latin America and the Caribbean, inspired by the United States government, expressed in the theory of National Security, and guided by the principle of the internal enemy, which was systematically instilled in the police and military forces of the continent. According to this theory, any political opposition, any form of social dissent, any popular expression advocating for social, political and economic transformation, was part of the Soviet Union’s global domination plan, and was therefore made up of enemies who should be exterminated. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, this theory continued to be followed and enforced in our country. (FARC-EP, undated).

A significant change in the treatment of the armed conflict by the Colombian government took place in 2012. On September 4, the FARC-EP and the Colombian government led by President Juan Manuel Santos announced direct, face-to-face approaches to a process of negotiation in order to end the armed conflict between them. Although this Peace Process was not the first attempt to find a peaceful solution to the conflict — there had been other such attempts, starting in the 1980s — it did become a landmark in the recent treatment of internal confrontation because it recognized the status of guerrilla groups as political actors, allowing for a search of an end to the armed conflict through negotiation, an alternative that was rejected in the first decade of the twenty-first century by the government of Álvaro Uribe Vélez, who maintained that direct confrontation with outlawed groups was the best strategy.

Thus, the beginning of these peace dialogues signaled a break from the treatment given to the internal conflict by previous governments, especially those of Álvaro Uribe Vélez (2002-2006 and 2006-2010). It must be remembered that this president supported a policy of military confrontation with outlawed armed groups, known as the Democratic Security Policy (Política de Seguridad Democrática). Indeed, his first term began in 2002 with a speech in which he defended direct confrontation with belligerent groups as the shortest route to end armed conflict in Colombia. In his inauguration speech, Uribe Vélez spoke about the Democratic Security Policy in these terms:

Our concept of democratic security demands that we strive to seek an effective protection of citizens regardless of their political beliefs or wealth level. The whole nation cries out for calm and security. No crime can be directly or obliquely justified. No kidnapping must find any policy that justifies it. I understand the pain of our country’s mothers, orphans, and displaced people. In their name, I will search my soul every morning so that my actions of authority have the purest intention and the noblest completion. I will affectionately support our country’s Armed Forces, and we will encourage millions of citizens to come to their help (El Tiempo, 2002).

Besides a direct confrontation with the “internal enemy”,1 Uribe Vélez’s political wager denied, at least in the dimension of discourse, the internal armed conflict. This implied a different way of understanding the logic of armed confrontation between the State and the different outlawed actors2, while justifying military action against guerrilla groups.

In contrast, the Peace Dialogues leading to the Agreement for the End of the Conflict and the Construction of a Stable and Lasting Peace between the government of President Juan Manuel Santos and the FARC-EP managed to consolidate by 2012 a joint working agenda along five guidelines for negotiation: (I) Comprehensive Rural Reform, (II) Political Participation, (III) Solutions to the Problem of Illegal Drugs, (IV) Victims and Transitional Justice, and (V) Ceasing the Armed Struggle and Ending the Conflict.

To guarantee this negotiation process, the actors in conflict acknowledged the participation of Cuba and Norway as guarantors of the process who would provide follow-up on the compliance of the commitments made, as well as the implementation, verification and approval of the peace agreements.

The timetable for negotiation marked the second half of 2016 as the culmination point of the dialogues for peace, since by September of that year the five points being discussed would be consolidated, and the final document of the Peace Agreement would be presented to the public. The mechanism chosen to validate the agreements was a referendum, which would allow the citizens of Colombia to express their support for the Peace Agreement to end the conflict and build a stable and lasting peace.3 After being rejected in the Referendum for Peace (Plebiscito por la paz),4 the peace process entered a period of renegotiation in which, based on the demands of the citizens through different media as well as the inclusion of some points advocated by the opposition, some of the agreements made were redefined. On November 30 the Colombian Congress, as a secondary constituent, validated this agreement, opening the way for its implementation.

The complex political panorama after the peace negotiations, as well as a growing social demand to understand the logic of the armed conflict and the implications of a potential post-conflict,5 led to pronouncements in the civil society asking for spaces for dialogue and education on the Peace Agreements.

Education is a fundamental pillar to achieve the promised — and in some sense demanded— culture of peace and reconciliation. Among the actions undertaken in this respect, it is worth mentioning the creation of the “Lectures on Peace” (Cátedra de la Paz), defined this way in Decree 1038 of 2014:

The Lectures on Peace must foster the process of appropriation of knowledge and competences related to territory, culture, social and economic context, and historical memory, with the aim of reconstructing the social tissue, promoting prosperity for all and guaranteeing the effectiveness of the principles, rights and duties consecrated in the Constitution (Congreso de la República de Colombia, 2014).

The Lectures on Peace constitute an effort by the State to address the manifestations of the conflict in the country through formal education, as well as to propose a formative component that presents strategies for the peaceful resolution of conflicts.

On the other hand, among the social demands for an education for peace, a number of them go beyond the objectives of the Lectures on Peace. Although it is desirable that educational institutions feature a space for education on peace, this leaves out a large part of the population who also demand spaces for deliberation and education on the armed conflict and a culture for peace. This fully justifies an education on the framework of the Peace Agreements within a post-conflict scenario.

2 The System for Citizen Education on Participation

The System for Citizen Education on Participation (SFCP) is the pedagogical proposal of the Secretariat for Citizen Participation of the Medellín Mayor’s Office to channel the formative processes that have taken place in the city in their term.

The main aim of the SFCP is an education in the skills and capabilities required to exercise citizenship. To achieve it, it advocates a critical, responsible and active exercise of citizenship based on the defense of democratic participation with a territorial approach, which will result in practices of coexistence, peaceful resolution of conflicts and exercises in social control:

This pedagogical perspective is structured upon a proposal founded on critical pedagogy and a capabilities approach from which an educational proposal can take shape that is coherent with the call to promote citizen participation that strengthens an active citizenship and contributes to comprehensive human development, as well as to a dynamic, participative society with a political culture, capable of transforming the city through equality, inclusion, coexistence and transparency (Secretaría de Participación Ciudadana, Alcaldía de Medellín, 2015a, p. 4).

The SFCP pedagogical proposal articulates different pedagogical approaches, dimensions, capabilities and problematizing guidelines (see Figure 1). We will describe the elements considered in this pedagogical proposal, and then analyze how these elements are linked to the approach to the thematic guidelines prioritized in the Post-Conflict Diploma Course.

Source: Secretaría de Participación Ciudadana, Alcaldía de Medellín, 2015a, p. 36

Figure 1 System for Citizen Education on Participation

2.1 Approaches of the SFCP

The SFCP, nourished by the postulates of critical pedagogy, social pedagogy and popular education, is supported by pedagogical approaches that enable an educational practice outside the traditional models, which most of the time rely on a one-way exchange of information from the teacher to the student, with magisterial classes in a classroom.

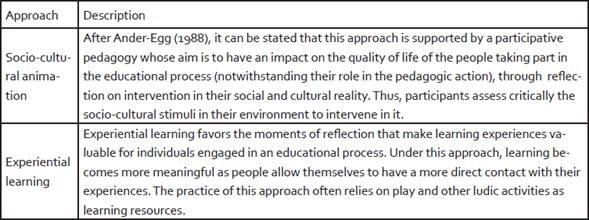

In this sense, educational practices conceived within the SFCP are supported by two pedagogical approaches: (I) socio-cultural animation, and (II) experiential learning (see Table 1).

Table 1 Pedagogical approaches of the SFCP

Source: Based on (Secretaría de Participación Ciudadana, Alcaldía de Medellín, 2015a, pp. 21-22).

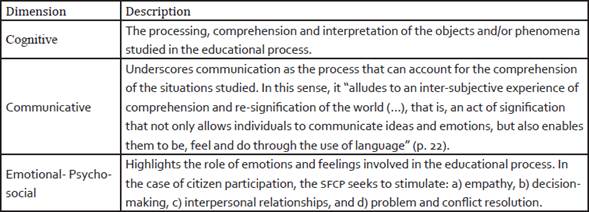

2.2 Transversal dimensions of the SFCP

The transversal dimensions of the SFCP refer to the areas of the individual involved in the educational process. This pedagogical proposal revolves around three transversal dimensions affected by pedagogical practices: (I) cognitive, (II) communicative, and (III) emotional-psychosocial (see Table 2).

Table 2 Transversal dimensions of the SFCP

Source: Based on (Secretaría de Participación Ciudadana, Alcaldía de Medellín, 2015a, pp. 22-23).

2.3 Capabilities for Human Development

Philosopher Martha Nussbaum eschews the idea of education by competences, claiming that when pedagogy favors this component it loses sight of the individual, who participates in it not as a tabula rasa, but through particular experiences that enable — and condition — a comprehension of the situations addressed. Thus, for Nussbaum (2012), it is more effective to appeal to the skills and capabilities of the individuals than to focus on the competences, which would focus on the group’s acquisition and mastery of the information through continuous comparison among the individuals who participated in an educational process.

Nussbaum's pedagogical proposal is directly linked to human development and the consolidation of democratic societies. Hence, the Secretariat for Citizen Participation of the Medellín Mayor’s Office (2015), points out that: “Nussbaum’s proposal starts with a question about the horizon of democratic societies from a human development approach, and thus the need to «cultivate humanity» or educate for global citizenship” (p. 24).

According to Nussbaum, three capabilities must be especially stimulated for the consolidation of democratic societies with high levels of human development: (I) self-examination, (II) intercultural dialogue, and (III) empathy, understood as the ability to put oneself in the place of the other.

2.4 Approaches by capabilities for participation in the framework of the SFCP

Among the many capabilities and skills that may be stimulated in educational processes, the SFCP underscores those approaches by capabilities that are most relevant for an education in citizen participation: (I) critical judgement, (II) affiliation, (III) ethical praxis, (IV) social control of their environment, and (V) imagination (see Table 3).

Table 3 Approaches by capabilities for participation in the SFCP

Source: Based on (Secretaría de Participación Ciudadana, Alcaldía de Medellín, 2015a, pp. 29-31).

2.5 Problematizing guidelines of the SFCP

The Secretariat for Citizen Participation of the Medellín Mayor’s Office defines the problematizing guidelines of the SFCP as “those that bring together open situations around a specific issue. Their openness allows for the coexistence of viewpoints, approaches and alternatives to address them” (2015a, p. 32). Four problematizing guidelines are proposed for the SFCP: (I) coexistence and conflict resolution, (II) territorial development, (III) social control, and (IV) inclusion (see Table 4).

Table 4 Problematizing guidelines of the SFCP

Source: Based on (Secretaría de Participación Ciudadana, Alcaldía de Medellín, 2015a, pp. 33-35).

3 Post-Conflict Diploma Course. A Case study

Within the framework of strategies to increase democracy, incentives to the decentralization of the state, co-responsibility in the improvement of the indices of transparency in the use of public resources, and a mechanism to strengthen and promote relationships between the state and the civil society, the program of “Participative Budgeting and Local Planning (PPYPL, Presupuesto Participativo y Planeación Local) began to be implemented in 2004 in the city of Medellín, Colombia.6 PPYPL is presented as a space where local government, community organizations and citizens meet through a “political contract” — in the words of Boaventura de Sousa Santos (2007) — that makes it viable to prioritize resources in favor of initiatives derived from proposals made by the population itself.

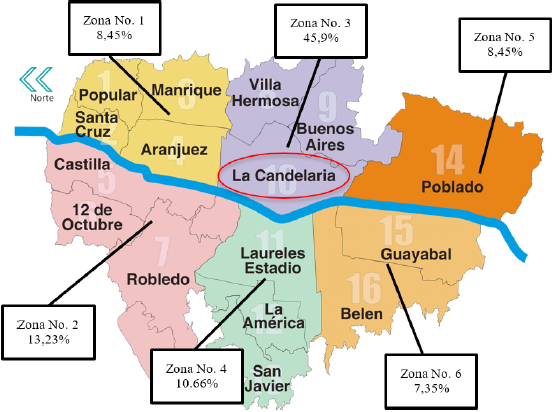

Year after year, the delegates of the 16 communes of Medellín, as well as its five corregimientos,7 advance the prioritization of recourses in order to attend to their territories’ needs in infrastructure, education, culture or sports. As a result, at the end of 2015 and the beginning of 2016 the delegates for Commune 10, La Candelaria, proposed to create a space for social formation on post-conflict issues, which gave rise to the structuring of the project of the Post-Conflict Diploma Course. The following pages aim to contextualize the scope of the project, based on four references.

First, we describe the constitutive elements of the project; that is, we characterize the population it benefits and evaluate the objectives proposed by the Diploma Course. Secondly, we present the pedagogical and methodological proposal involved in the Diploma Course, as an embodiment of the System for Citizen Education on Participation (SFCP) mentioned above.

Finally, we give an account of the results of the Diploma Course, which includes the presentation of one of the key products of the project: the writing and publication of the critical and insightful text “The Post-Conflict Diploma Course: A Compilation of Collective Presentations”.

3.1 The Post-Conflict Diploma Course: characterization and scope of the project

The “Inter-Administrative Contract to Develop an Educational Process on Post-Conflict Issues” (from now on “Post-Conflict Diploma Course”), prioritized by the program of Participative Budgeting of Commune 10, La Candelaria, in Medellín, aimed to address, from a historic, critical and purposeful perspective, the main challenges faced by the negotiation process between the National Government of President Juan Manuel Santos and the guerrilla of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People’s Army (FARC-EP).

Thus, the project aimed to have an impact on 210 inhabitants of Medellín, with diversity as the main characteristic of the group that was to be its beneficiary. The following are the most salient elements of the characterization of the population.

Figure 2 shows the degree of dispersion of the participants in the Diploma Course, which leads us to conclude that its main impact was urban. However, we must point out that resources were prioritized by Commune 10, La Candelaria, and even though there was a great deal of participation form citizens of other communes of Medellín, the highest level of participation was indeed from La Candelaria, located in Zone 3 of Medellín, with 45,9% of all the participants.

Source: our own

Figure 2 Territorial distribution of the participants in the Post-Conflict Diploma Course

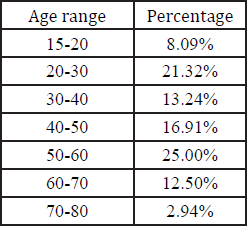

Another important factor was the diversity in the ages of the participants. Figure 3 shows their age ranges. Significantly, participants in the Diploma Course ranged from 16 to 72 years old. This diversity is a key element because it posed challenges and offered opportunities for the pedagogical and methodological proposal of the educational process.

Another salient feature was the difference in educational level of the participants. Figure 4 shows that among the 210 participants the rate of illiteracy was 0. It also shows that there was a certain degree of dispersion in the educational level, from participants who had only finished elementary to others who had PhDs. Finally, the Figure shows that most participants were undergraduates (36,40%), followed by those who had finished secondary school (33,46%), and in third place those who had a professional specialization (10,66%).

Finally, a significant feature of the Diploma Course was the high number of women participants (62%), contrasting with that of men (38.24%). Additionally, 1.84% of participants were members of the LGTBI community. The percentage of participation of women is significant in spaces where their presence and active participation are gradually growing, in a country where, according to the government’s Unified Registry of Victims (Registro Único de Víctimas) there had been, up to March 2017, a total of 8.100.180 victims of the armed conflict, 4.021.278 (49.68%) of whom have been women and 4.018.447 (46.60%) men.8

3.2 Pedagogical and Methodological Approach of the Post-Conflict Diploma Course

“Education for participation” was the distinctive feature of the pedagogical approach designed for the Post-Conflict Diploma Course, after the proposal of the System for Citizen Education in Participation (SFCP), of the Secretariat of Citizen Participation of the Medellín Mayor’s Office. Thus, critical pedagogy, social education and popular education were the main references considered to structure the course’s pedagogical approach.

Turning to these approaches implied re-signifying the individual through his or her interaction with the educational process. Consequently, the development of a theoretical-conceptual component was accompanied by a critical and reflective perspective that eventually led to a purposeful proposal from those who interacted in the teaching-learning process. Thus, the pedagogical proposal was able to overcome the traditional pedagogical schemes associated to the false premise “The teacher knows and is therefore the active subject; the learner does not know, and is the passive subject waiting to be instructed”.

Hence, the Diploma Course aimed to forge a collective reconstruction of the factors, actors and scenarios involved in Colombia’s internal armed conflict, focusing on the peace negotiations between the government and the FARC-EP in La Habana, Cuba. Therefore, as proposed by the SFCP, the educational process had to involve the development of the participants’ capabilities and skills, in order to have a structural comprehension of the different phenomena addressed by the Diploma Course.

By adopting the SFCP as a transversal system to the individuals being educated, a pedagogical act was presented as a form of active participation, “a participation that promotes the shaping of a social, ethical and political subjectivity that favors conscious reflection and practices to transform the realities that require it” (Secretaría de Participación Ciudadana, Alcaldía de Medellín, 2015a, p. 40).

To guarantee such a pedagogical exercise at the methodological level, the Diploma Course was structured around three types of activities and a transversal component (see Figure 6). The process was conducted, as proposed by Paulo Freire (1990), at a momentum of critical self-reflection of the time and space we live in, to be part of history as authors and actors, not just mere spectators.

Seeking to generate a broad and motivating context for the Diploma Course, the first type of activity was the “Seminar-Workshop” mode, spaces that allowed for each one of the six basic themes of the Diploma Course: (I) Comprehensive Rural Reform, (II) Political Participation, (III) Victims and Transitional Justice, (IV) Illegal Drugs, (V) Ceasing the Armed Struggle and Ending the Conflict, and (VI) Peace and Territory.

The Seminar-Workshops were structured around two moments: the first, a dissertation by an expert on the issue, and the second, a group workshop where the participants in the Diploma Course took a leading role by focusing the expert’s contributions on an analysis through their daily life experiences of their immediate environment. Thus debates, biography writing, design of timelines, Q and A’s, among other strategies, were used to conduct the workshops.

Without a doubt, one of the key foundations of Critical Pedagogy is precisely its dialogical vocation, a feature that enables the meeting — and contrast — of experiences and positions on the phenomena that constitute our collective memory. As Giroux points out, “democracy demands critical forms of education and pedagogical practices that provide a new ethos of freedom and a reaffirmation of collective identity as the central issues of a vibrant culture and a democratic society” (1997, p. 34).

The start of the Seminar-Workshops required the participation of the 210 students of the Diploma Course. The main aim was to engage all of them in each of the Seminar-Workshops, allowing for thematic discussions that would be of great value in subsequent stages of the project.

Following that were the Formative Workshops. Unlike the Seminar-Workshops, whose objective was to impact all of the 210 participants of the Diploma Course, the Formative Workshops were conducted as Study Groups: the 210 participants separated into 6 Study Groups of 35 persons, each corresponding to one of the thematic lines of the Diploma Course, meeting in 15 sessions along the course.

Rather than propitiate a generic educational space where participants had basic notions of each central issue, the Diploma Couse opted for a comprehensive educational process that, along the lines of Participative-Action-Research, allowed for not only a linear historical review of the phenomena, but also an intensive research exercise by the participants. That is, the pedagogical approach allowed the process to be oriented from an inclusive perspective, on the premise that in the Popular Education approach the participants in the Diploma Course are actors who are part of the phenomena to be addressed, and therefore subject to direct and indirect consequences of such phenomena, which makes them at the same time the subject and the object of research.

Finally, activities 1 and 2 — that is, the Seminar-Workshops and the Formative Workshops— were followed by a third component: Socio-Cultural Animation Activities (ASC). In the framework of citizen education, the Secretariat of Citizen Participation of the Medellín Mayor’s Office defines the ASC as:

Discourse and practice focused on a broad concept of culture that calls for pluralism and the participation of social actors in making citizen, personal and collective commitments that lead to the democratization of culture, understood as a creative process and a social patrimony, and not as the passive consumerism produced by ideological manipulation (2015b, pp. 6-7).

In this respect, Ander-Egg proposes the ASC as “a social technology that, based on participative pedagogy, seeks to act in different areas of the quality of life by promoting, encouraging and channeling people’s participation in their own socio-cultural development” (1988, p. 42). Although the ASC lacks a body of theory of its own, and there is a great deal of discussion around its scientific canon, its fundaments are oriented rather as a consequence of a social movement of cultural recognition since the 1970s. Thus, the ASC is a collective reaction to the unacceptability of a culture that restricts its production and transmission to an intellectually and/or economically privileged minority. In contrast, the ASC is proposed as a project that aims to have citizens intervene directly in a culture they live daily, and in whose creation they must participate (Quintana, 1986).

Hence, the Post-Conflict Diploma Course was seen as an in-classroom and out-of-classroom process. While components 1 and 2 took place mostly within the classroom, the Socio-Cultural Animation component took place in a place that was open to the public, with the aim of having the participation and active communication of the citizens in the street. This combined the technical and artistic resources of the “Innovarte” Artistic Corporation with the active integration of the participants in the Diploma Course, seeking to have dialogical exercises with the community.

The ASC component was carried out in downtown Medellín which, as part of the city’s historical center, is one of the main spaces where its inhabitants meet. The staging was a conjunction of five artistic expressions:

> Comprehensive Rural Reform: A play. A short scene featuring a dialog that depicts the drama of 6.9 million Colombians who were victims of forcible displacement.

> Political Participation: A ballot box was used to simulate a voting scene, but rather than deposit a vote, passersby had the opportunity to write a reflection on the peace and reconciliation process. The activity was accompanied by a musician playing a chirimía, a traditional instrument.

> Victims and Transitional Justice: A ludic contemporary dance performance showing a critical image of the victimization processes, presenting not only the power relationships (victims/victimizers) against their bodies, but also against their soul, against the environments where each one of them lives.

> Illegal Drugs: Around a comedic scene that led to a reflection around three characters immersed in the cycle of narcotics: production, commercialization and use of illegal drugs.

> Final Agreements: A clown performance showing the possibility of a negotiated solution to the armed conflict, with two specific moments: (I) a (self) reflection on the humiliations of the war, and (II) an allegory of peace, as a way of overcoming the conflict.

The ASC activities encouraged a dialogue between the participants in the Diploma Course and the rest of the city, an apt scenario for a call to reconciliation. These activities took place in November 2016, that is, a month after the Referendum for Peace held on October 2, where the “No” votes won with 50.21% against the 49.78% of the “Yes”. This immersed the country in a deep political polarization, requiring the formulation of strategies aimed at a national call for “reconciliation”, especially because Medellín — the second largest city in Colombia — was the place where the “No” defeated the “Yes” more overwhelmingly.9

Thus, the country’s social and political context became the ideal laboratory to implement the ASC activities by providing a social pedagogy experience, while at the same time the members of the Study Groups were able to speak with the passersby. A space was generated to sensitize, socialize and disseminate the knowledge built collectively on the thematic issues of the Diploma Course, which refer directly to the issues discussed in the peace process between the government of Colombia and the FARC-EP.

3.3 Compiling the Collective Presentations. A Citizen Research Exercise to Understand the Peace Agreements

As the culmination of the pedagogical and methodological proposal of the Post-Conflict Diploma Course, it would be advisable to consider the Participative-Action Research methodology (LAP) for the planning and execution of the research process, which led to the creation of the text: Compilación de Ponencias Colectivas (“A Compilation of Collective Presentations”).

The Collective Presentation emerged as “the product of a group effort to comprehend a relevant issue under the standards of academy and pedagogical formulation… [besides] compiling reflections and contributions made by the members of each group towards a global analysis of the La Habana Agreements, which are addressed from different approaches and views” (Alcaldía de Medellín, 2016, p. 14).

In its structure, the Collective Presentation includes, first, an introductory and methodological section, which explains both the pedagogical foundations and the academic and research rigor of the exercise. It also reviews (from a constructive perspective) the potential and limitations of this kind of exercises, noting that the diversity of the population was a factor that allowed for wider analytic and reflective horizons, requiring pedagogical strategies that would guarantee an assertive educational process.

Then there are six articles, each corresponding to one of the thematic guidelines of the Study Groups. Personal and group motivations, previous knowledge, as well as the ethical inclinations and the citizen engagement of the participants, determined the formulation and writing of the articles.

Thus, the Post-Conflict Diploma Course presented a set of methodologies aimed at a critical reflection and debate on the themes of the peace agreements, allowing for the implementation of strategies that not only had an impact on the territory (as in the case of the socio-cultural animation component), but also left behind a body of work that was the product of citizen participation. Consequently, the Compilation of Collective Presentations was formulated as a key link within the Diploma Course because it worked, through the popular education approach, as a vehicle to strengthen the participants’ skills and capabilities and have a positive impact on their environment (at different levels of proximity).

Conclusions

Worthy of attention is the vocation of the inhabitants of Medellín to understand the — rather complex — political circumstances of the peace agreement negotiations. While the city was mostly against what was agreed between the government of Colombia and the FARC-EP, the participants in the Post-Conflict Diploma Course propitiated spaces to exchange ideas from different political horizons where, regardless of one's personal political position, the main aim was to understand the phenomenon that gave rise to the educational space.

For this reason, the citizens' motivation to assume a critical and informed position about the peace negotiations led to the formulation of an educational process that, based on the references of critical pedagogy, social pedagogy, and popular education, enabled a “city dialogue” in which the academic component ran along the territorial impact of the socio-cultural animation activities so that in the end both elements combined to develop social research skills.

Also worthy of note is the structured proposal that the Medellín Mayor’s Office has generated in the framework of informal education, with the aim of strengthening and improving not only the amount of citizen participation, but also the qualification of leaders on a territorial level. The System for Citizen Education on Participation becomes a key input for processes of emancipation in which a critical and purposeful attitude enables a real impact on the communities.

Thus, the group of citizens who participated in the project was evidence of a continuous dialogue between micro-politics (the community) and macro-politics (the institutional sphere of the state), an interaction that propitiates participative environments that shed light on social demands and support for social, political and cultural phenomena. Following Almond and Verba’s ideas, the political culture of the participants in the Post-Conflict Diploma Course may be best described as participative.9

REFERENCES

Alcaldía de Medellín (1996). Diplomado en Posconflicto. Compilación de ponencias. Medellín: Alcaldía de Medellín. [ Links ]

Almond, G. y S. Verba (1963). Un enfoque sobre la cultura política. En La cultura cívica. Madrid: Euroamérica. [ Links ]

Amador, J. C. (2014). Del “posacuerdo” al posconflicto. Gaceta UDebate. Bogotá: Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas. < http://editorial.udistrital.edu.co/udebate/20141122.pdf > [Consultado: 2 abril 2017]. [ Links ]

Ander Egg, E. (1988). ¿Qué es la animación socio cultural? Santa Cruz de Tenerife: Centro de Cultura Popular. [ Links ]

Concejo de Medellín (2007). Acuerdo Municipal 43. Por el cual se crea e institucionaliza la Planeación Local y el Presupuesto Participativo en el marco del Sistema Municipal de Planeación - Acuerdo 043 de 1996- y se modifican algunos de sus artículos. < https://www.medellin.gov.co/irj/portal/medellin?NavigationTarget=navurl://200791099a6882e838eafa3f675a7b5f > [Consultado: 4 marzo 2017]. [ Links ]

Congreso de la República de Colombia (2011). Ley 1448 de 2011: Por la cual se dictan medidas de atención, asistencia y reparación integral a las víctimas del conflicto armado interno y se dictan otras disposiciones. < http://www.alcaldiabogota.gov.co/sisjur/normas/Norma1.jsp?i=43043 > [Consultado: 21 febrero 2017]. [ Links ]

______ (2014). Ley 1732 de 2014: Por la cual se establece la Cátedra de la Paz en todas las instituciones del país. <http://wsp.presidencia.gov.co/Normativa/Leyes/Documents/LEY%201732%20DEL%2001%20DE%20SEPTIEMBRE%20DE%202014.pdf> [Consultado: 17 marzo 2017]. [ Links ]

El Tiempo (2002). Discurso de posesión del presidente Álvaro Uribe Vélez. < http://www.eltiempo.com/archivo/documento/MAM-1339914 > [Consultado: 21 febrero 2017]. [ Links ]

Farc-Ep (s/f). Quiénes somos y por qué luchamos. < http://www.farc-ep.co/nosotros.html > [Consulado: 15 febrero 2017]. [ Links ]

Freire, P. (1990). La naturaleza política de la educación: cultura, poder y liberación. Barcelona: Paidós. [ Links ]

Giroux, H. (1997). Los profesores como intelectuales: hacia una pedagogía crítica del aprendizaje. Barcelona: Paidós. [ Links ]

Nussbaum, M. (2012). Crear capacidades: propuesta para el desarrollo humano. Barcelona: Paidós. [ Links ]

Presidencia de la República de Colombia (2016). Acuerdo final para la terminación del conflicto y la construcción de una paz estable y duradera. < http://www.acuerdodepaz.gov.co/sites/all/themes/nexus/files/24_08_2016acuerdofinalfinalfinal-1472094587.pdf > [Consultado: 8 abril 2017]. [ Links ]

Quintana, J. M. (1986). La animación sociocultural en el marco de la educación permanente. Madrid: Narcea. [ Links ]

Ramírez Brouchoud, M. F. (2012). Transformaciones del estado en el gobierno local: la nueva gestión pública en Medellín. Reflexión Política 14(28), pp.82-95. < http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/110/11025028007.pdf > [Consultado:13 febrero 2017]. [ Links ]

Santos, B. (2007). Dos democracias, dos legalidades: el presupuesto participativo en Porto Alegre, Brasil. En Santos, B. y C. Rodríguez. El derecho y la globalización desde abajo: hacia una legalidad cosmopolita. México: Anthropos / Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Participación Ciudadana, Alcaldía de Medellín (2015a). Propuesta Pedagógica y Procedimental. Sistema de Formación Ciudadana Para la Participación. Medellín: Alcaldía de Medellín [Documento elaborado por el equipo de la Unidad de Investigación y Extensión para la Participación de la Subsecretaría Formación y Participación, Secretaría de Participación Ciudadana. Versión 3]. [ Links ]

______ (2015b). Pedagogía Social y Formación Ciudadana. Medellín: Alcaldía de Medellín [Documento elaborado por el equipo de la Unidad de Investigación y Extensión para la Participación de la Subsecretaría Formación y Participación, Secretaría de Participación Ciudadana]. [ Links ]

Sylva Sánchez, I. (2011). Denominaciones oficiales de los sujetos de acción armada ilegal con presunciones políticas. Colombia, 1998-2006. Tesis de maestría, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín. [ Links ]

Valcárcel Torres, J. M. (2008). Beligerancia, terrorismo y conflicto armado: no es un juego de palabras. International Law: Revista Colombiana de Derecho Internacional, 13, pp. 363-390. < http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=82420293011 > [Consultado: 12 abril 2017]. [ Links ]

Velásquez Rivera, E. (2002). “Historia de la Doctrina de la Seguridad Nacional”. Convergencia. Revista de Ciencias Sociales 9(27), pp.11-41. < http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=10502701 > [Consultado: 12 abril 2017]. [ Links ]

1This category was used by the National Security Doctrine to refer to the actors who, within the states, opposed the United States’ foreign policy during the Cold War. It justified military confrontation with agents who disseminated political ideals resembling communism or openly pro-USSR. Edgar de J. Velásquez Rivera’s work clearly illustrates this issue (See Velásquez, 2002).

2During his two presidential terms, Uribe Vélez referred to the FARC-EP guerrillas as “terrorists”, denying them the status of belligerent group, which would have forced him to acknowledge them as a participating actor in the internal conflict (See Valcárcel, 2008). Professor Iván Sylva Sánchez’s work clarifies this issue. In his Master’s Degree thesis Denominaciones oficiales de los sujetos de acción armada ilegal con presunciones políticas. Colombia, 1998-2006, he shows how, in spite of denying the armed conflict in his discourse, fomer president Álvaro Uribe Vélez – in his first term – relied on categories linked to internal conflict to describe his policies of confrontation between Colombia’s Armed Forces and the outlawed groups (See Sylva, 2011).

3Representatives of the Colombian government and the FARC-EP met in Cartagena on Monday, September 26, to sign the Peace Agreement for the End of the Conflict and the Construction of a Stable, Lasting peace. On Sunday, October 2, citizens were consulted in the Referendum for Peace on their support for this agreement.

4According to the National Registry of the Civil State, 50,21% of the voters (6’431.376) voted “No”, while 49,78% of the voters (6’337.48) voted “Yes”.

5This category was coined by the national government to describe the reality after the implementation of the peace agreements. However, some sectors of society, significantly among them the academic sector, noted how imprecise this notion was, because although a successful agreement could be reached with a guerrilla group such as the FARC-EP, the internal conflict involved other actors who, by the time of the negotiation, had resorted to hostilities to defend their political ideal(s). Juan Carlos Amador, Director of the Institute for Pedagogy, Peace and Urban Conflict (2014), was among the first to note this distinction (See Amador, 2014).

6 Ramírez Brouchoud’s research (2012) is a contribution to understand the logic of Local Planning and Participative Budgeting vis-a-vis the dynamics of a new public administration.

7Administratively, the city of Medellín is made up of 16 communes in its urban sector and 5 corregimientos in its rural sector.

8The National Registry of Victims’ updated information can be consulted at <http://rni.unidadvictimas.gov.co/RUV>

9Medellín and Bucaramanga were two of the capital cities where the “No” votes won. In the case of Bucaramanga, the “No” votes were 55.11% and the “Yes” 44.88%, while in Medellín the differences in the percentage were more marked: 62.97% “No” to 37,02% “Yes”. For further information see <http://plebiscito.registraduria.gov.co/99PL/DPL01001ZZZZZZZZZZZZ_L1.htm>

9According to Almond and Verba [1963], a participative culture is characterized by having: (i) members oriented towards the political system in general, (II) citizens responsive to the input and output of the political system when faced by political junctures, and (III) an active role in the political community.

Received: May 01, 2017; Accepted: July 11, 2017

texto en

texto en