Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

Print version ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.14 n.79 México Sep./Oct. 2023 Epub Oct 06, 2023

https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v14i79.1353

Scientific article

Useful plants in the rural area of Linares municipality, Nuevo León

1Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León,. México.

The useful flora and uses of plants in the rural area of Linares, Nuevo León were analyzed. A total of 180 semi-structured surveys were conducted in six ejidos. 75 families, 194 genera and 253 species with ethnobotanical use were recorded. The main categories of use were: ornamental (105 species), medicinal (83), food (6) and timber (25); the remaining 34 species are used as fodder, cosmetics and beliefs. Cactaceae (19), Fabaceae (15), Asteraceae (15), Poaceae (15), Lamiaceae (12), Solanaceae (6), Asparagaceae (6), and Rutaceae (4) recorded the highest number of taxa. Of the total number of identified species, 120 are native, and 133 are exotic. As for the medicinal use, Allium sativum, Aloe vera, Echinocereus poselgeri, Equisetum laevigatum, Croton suaveolens, Mentha spicata, Litsea glaucescens and Ruta graveolens were the most widely used. The main timber species were Prosopis glandulosa, Vachellia farnesiana, Ebenopsis ebano, Havardia pallens, Quercus canbyi, Carya illinoinensis, Pinus cembroides, P. montezumae, and P. teocote. For the Informant Consensus Factor (ICF), medicinal plants are mainly used to cure ailments of the respiratory, circulatory, reproductive, and digestive systems. The taxa with the highest Use Value Index (UVI), equal to 1 in every case, were Dysphania ambrosioides, Allium cepa, and A. sativum. In regard to the Fidelity Index (FI, %), the highest percentages corresponded to Artemisia ludoviciana, Cymbopogon citratus, and Hedeoma drummondii. The Linares rural region has a rich useful flora, which is mainly used as ornamental, medicinal, food, forage and timber.

Key words Ethnobotany; Linares; northeastern Mexico; Nuevo León; natural resources; traditional uses of plants

Se estudiaron la flora útil y los usos de las plantas del área rural de Linares, Nuevo León. Se realizaron 180 encuestas semiestructuradas en seis ejidos. Se registraron 75 familias, 194 géneros y 253 especies con uso etnobotánico. Las principales categorías de uso fueron: ornamental (105 especies), medicinal (83), alimento (6) y maderable (25), las 34 especies restantes son utilizadas como forraje, cosméticos y creencias. Cactaceae (19), Fabaceae (15), Asteraceae (15), Poaceae (15), Lamiaceae (12), Solanaceae (6), Asparagaceae (6) y Rutaceae (4) registraron el mayor número de taxa. Del total de especies identificadas, 120 son nativas y 133 exóticas. Respecto al uso medicinal, Allium sativum, Aloe vera, Echinocereus poselgeri, Equisetum laevigatum, Croton suaveolens, Mentha spicata, Litsea glaucescens y Ruta graveolens resultaron las más utilizadas. Las principales especies maderables fueron: Prosopis glandulosa, Vachellia farnesiana, Ebenopsis ebano, Havardia pallens, Quercus canbyi, Carya illinoinensis, Pinus cembroides, P. montezumae y P. teocote. Para el Factor de Consenso del Informante (FCI) las medicinales se utilizan, principalmente, para curar males de los sistemas respiratorio, circulatorio, reproductivo y digestivo. Los taxa con los valores más altos del Índice de Valor de Uso (IVU) fueron Dysphania ambrosioides, Allium cepa y A. sativum, todas con valor=1. Respecto al Índice de Fidelidad (IF, %), los mayores porcentajes correspondieron a Artemisia ludoviciana, Cymbopogon citratus y Hedeoma drummondii. La región rural de Linares posee una rica flora útil que se utiliza principalmente como ornamental, medicinal, alimenticia, forrajera y maderable.

Palabras clave Etnobotánica; Linares; noreste de México; Nuevo León; recursos naturales; usos tradicionales de plantas

Introduction

Mexico is a megadiverse country due to its geographic location and orography. It homes a high biological diversity, representing about 6 to 8 % of the planet's plant species (Rzedowski, 2006). Within this plant diversity, there are more than 30 000 taxa of vascular plants, at least half of which are used to satisfy human needs; from these, the medicinal ones are the most commonly used (Lira et al., 2016). The wide variety of climates and physiography allows the presence of great floristic richness, and consequently a great diversity of useful plants (Estrada-Castillón et al., 2022).

Ethnobotany studies the relationships among different human groups and their environment, and the use and harvest of plants in different cultures through time (Casas et al., 2014), and it is a useful tool for the rescue of knowledge on the use of plant resources (Zambrano-Intriago et al., 2015). Through cultural transmission, shared groups are formed with certain knowledge, but also with divergences in knowledge between individuals and social groups (Ochoa and Ladio, 2015).

Ethnobotany is a field of science with a multidisciplinary nature, since it refers to the relationships between human societies and plants (Martínez, 1994), and provides them with environmental goods and services, including provision (Hurtado et al., 2006). Today, the knowledge we have of plants is the historical result obtained by our ancestors, who learned by experimenting, i.e., by trial and error, and has been enriched by science to find new uses for the species (Estrada-Castillón et al., 2014).

Ethnobotany in semi-arid areas has gained importance in recent decades due to the loss of traditional knowledge and the degradation of natural habitats (Estrada-Castillón et al., 2017). Moreover, the availability of species strongly influences the knowledge of taxa and their uses for different purposes, especially for medicinal (Santos et al., 2016) and nutritional purposes (Thomas et al., 2009).

In northeastern Mexico, the management of plants by the rural population plays a key role in their existence (Estrada-Castillón et al., 2012). The state of Nuevo León has a high diversity of plants and vegetation types such as scrublands, chaparral, pine-oak forest, coniferous forest, halophyte grasslands and subalpine meadows (Estrada et al., 2015). Among the studies on useful plants and their uses in northeastern Mexico are those on the Cumbres de Monterrey National Park (Estrada et al., 2007); on the medicinal plants of south-central Nuevo León (Estrada-Castillón et al., 2012); on ethnobotany in Rayones, Nuevo León (Estrada-Castillón et al., 2014); on the useful plants of Bustamante, Nuevo León (Estrada-Castillón et al., 2017), on the ethnobotany of Cuatro Ciénegas, Coahuila (Estrada-Castillón et al., 2021), and on ethnobotany in Iturbide, Nuevo León (Estrada-Castillón et al., 2022). The objective of the present study was to increase the ethnobotanical knowledge of the flora of Linares municipality, Nuevo León, by identifying the use of the different plant species and their main categories of use.

Materials and Methods

Study area

Linares municipality is located in the central-eastern part of the state of Nuevo León and has an area of 2 445 km2 (INEGI, 1986). The climate is semi-warm, sub-humid with summer rains, an average annual temperature of 22 °C, and an average annual rainfall near 749 mm. The driest season is from June to August; the rainiest months are August and September (INEGI; 1986).

The flat surface of Linares municipality is covered by communities of the Tamaulipan thorny scrub (Estrada-Castillón et al., 2014). In the present work, a bibliographic search was carried out to review the inventory of plants of the area (Villarreal and Estrada, 2008). Subsequently, the area around Linares was visited for the purpose of collecting plant specimens. The recorded species were photographed in order to create an ethnobotanical database.

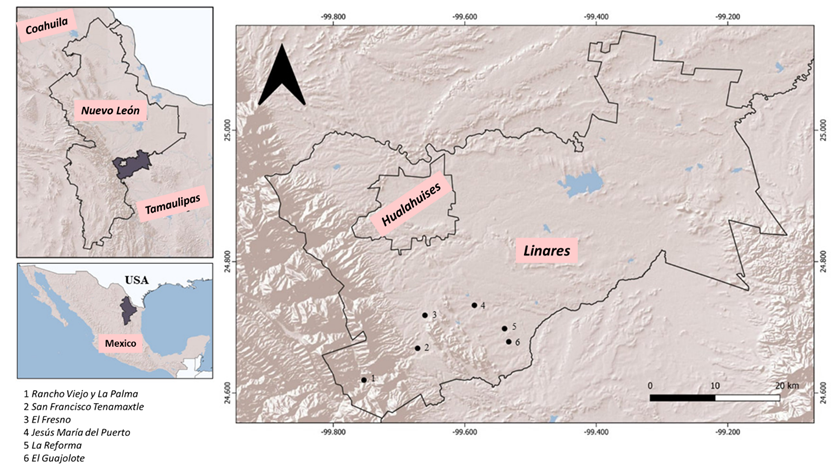

The identification of plant taxa was carried out based on specialized literature (Villarreal and Estrada, 2008). The collected specimens were stored in the herbarium (CFNL) of the Faculty of Forest Sciences of Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. Finally, the ejidos among whose inhabitants ethnobotanical use surveys were carried out were selected; they were Rancho Viejo y La Palma, San Francisco Tenamaxtle, El Fresno, Jesús María del Puerto, La Reforma and El Guajolote (Figure 1).

Laboratory work and fieldwork

Surveys

A total of 180 semi-structured surveys were conducted (interviewing 108 women and 72 men), 30 per ejido (Martin, 1995). The objective was to quantify the uses for each plant. The surveys were applied to men and women aged above 30 years, as it is considered that they know more species and their uses than younger people (Estrada-Castillón et al., 2014). The survey included at least four general questions relating to ethnobotanical knowledge: (1) What is the common name of the plant?, (2) How do you use it?, (3) What part of the plant do you use?, and (4) How do you prepare it? The surveys were conducted with the prior consent of each of the informants (ISE, 2006).

Data analysis

In order to find out the relationship between the age of the respondents and the number of known species of ethnobotanical use, a Pearson's correlation test was applied (Zar, 2010); in addition, an Analysis of Variance test was performed (Zar, 2010) by dividing the sample into age classes (nine, according to the Sturges rule). Information was analyzed with the statistical software PAST, version 4.03 (Hammer et al., 2001).

There are three main ethnobotanical indices for analyzing the importance of medicinal species (Heinrich et al., 1998; Estrada-Castillón et al., 2022): the Informant Consensus Factor (ICF) (Heinrich et al., 1998), the Use Value Index (UVI) (Zambrano-Intriago et al., 2015), and the Fidelity Index (FI) (López-Gutiérrez et al., 2014); the first two range between 0 and 1. The first expresses the result in an interval of 0-1, values closer to 0 indicate that the plants were chosen randomly or that there is no exchange of information about the use of the plants, while values close to 1 mean that few taxa are used by most informants to treat diseases grouped into the same category. The lower the calculated value, the greater the disagreement between informants regarding the use (Estrada-Castillón et al., 2022). The ICF is calculated using the following Equation:

Where:

nur = Number of plants used for each category

nt = Number of uses cited in each category

The UVI analyzes the local relevance of each of the species (Camou-Guerrero et al., 2008; Estrada-Castillón et al., 2022) and is calculated using the following formula:

Where:

Ui = Number of uses known by each informant for the species i

n = Total number of people interviewed

The Fidelity Index (FI) (Albuquerque et al., 2014; Estrada-Castillón et al., 2022) estimates the relative importance of each medicinal species according to the degree of consensus among the informants within a category of use, i.e., it refers to the consensus among informants regarding the therapeutic use of certain plant species to treat different categories of diseases and their medicinal efficacy. If a species shows greater consensus among respondents, it suggests that it is more effective because it has undergone trial-and-error selection over time. The FI is expressed in percentages and is calculated with this Equation:

Where:

Ip = Number of informants who independently indicated the use of a plant for the same particular condition

Iu = Number of informants who mentioned the species for a particular disease within a category of use

Results

Relationship between age and ethnobotanical knowledge

Pearson’s test showed no significant correlation (r=-0.026, n=180, p=0.729) between the age of individuals and the number of species with ethnobotanical use. The ANOVA test also showed no significant statistical differences between age classes and the number of species with ethnobotanical use (F=0.926, g.l.=179, p=0.496).

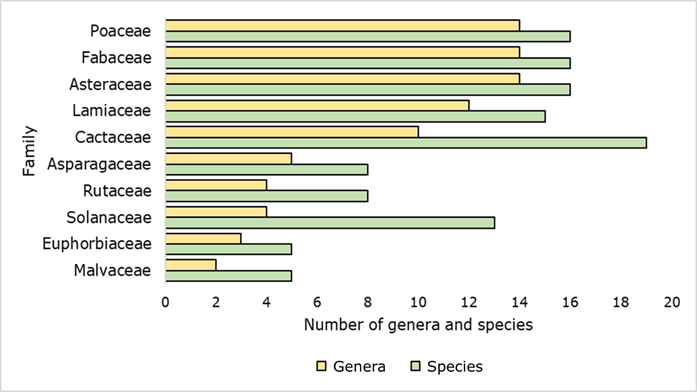

Diversity of families, genera, and species

A total of 253 plant species mentioned by the informants were recorded, included in 75 families and 194 genera. Figure 2 illustrates the families with the largest number of genera and species with ethnobotanical use. Of these, 47 % were native, and the remaining 53 % were exotic.

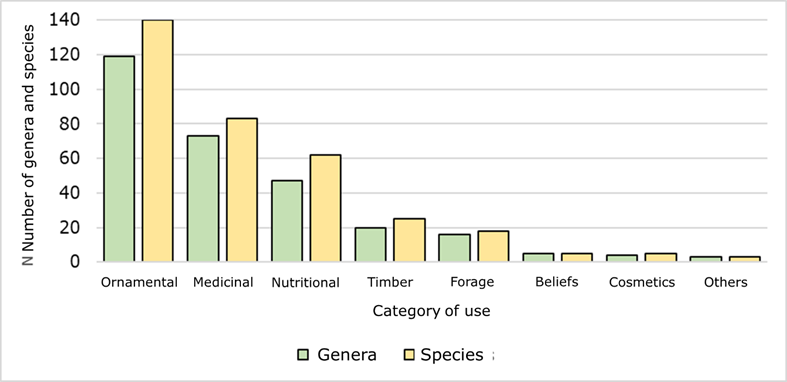

Category of use

According to the number of mentions, eight categories of uses were recorded, including ornamental, medicinal and food (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Main ethnobotanical use categories, number of genera and species in the rural areas of Linares municipality, Nuevo León, Mexico.

Ornamental

139 species with ornamental use belonging to 51 families and 105 genera were identified. The most representative families in terms of number of genera and species they include were Asparagaceae, Cactaceae, Crassulaceae, Fabaceae, and Lamiaceae. The most important characteristics for the selection of ornamentals were the color and scent of the flowers, the shape and size of the plant, as well as the amount of shade it provides. Ornamental shrubs were the most abundant (59), followed by herbaceous (51) and arboreal (29) species. Native herbaceous (33) and shrub taxa (18) outnumbered herbaceous and shrub exotics (31 and 28, respectively), while a higher number of tree exotics (21) than of natives (8) was recorded. The species with the highest number of mentions were: Rosa gallica L., Euphorbia milii Des Moul., Vinca minor L. and Hibiscus rosa-sinensis L.

Medicinal

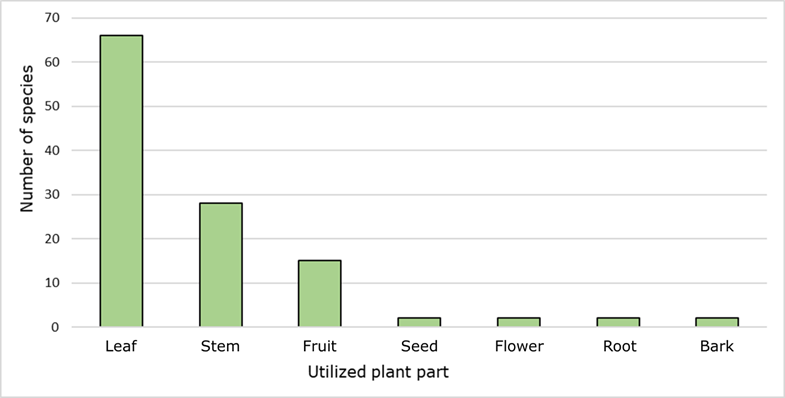

A total of 83 species with medicinal use, included in 36 families and 73 genera, were recorded. The body systems in which the treatments with these plants were applied were 13: digestive (34 species), respiratory (16), tegumentary (16), circulatory (13), endocrine (13), nervous (13), reproductory (8), urinary (8), sensory (5), osseous (4), muscular (3), lymphatic (3), and immunological (3). The main parts of the plant used were the leaves, the stems, and the fruits (Figure 4). The most common form of preparation was boiled in an infusion or tea (68 species), raw (23), anointed (13), cooked (3), and liquefied (3). The most important families in terms of genera and species used were Lamiaceae, Asteraceae and Rutaceae (Figure 5).

Figure 4 Main plant parts with medicinal use in the rural areas of Linares municipality, Nuevo León, Mexico.

Figure 5 Main families in relation to number of genera and species with medicinal ethnobotanical use in the rural areas of Linares municipality, Nuevo León, Mexico.

48 native and 35 exotic medicinal species were identified; native herbaceous species (21) were more commonly utilized than the 20 exotic herbaceous species; likewise, native shrubs (14 species) were more commonly utilized than exotics (2), while the numbers of medicinal trees utilized were similar: 13 native and 12 exotic. The medicinal plants with the highest number of mentions were: Croton suaveolens Torr., Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf, Bougainvillea glabra Choisy, Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt. y Mentha spicata L.

Nutritional

The food species recorded were 62, distributed among 47 genera. The best-represented families corresponded to Solanaceae (12 species), Apiaceae (five species), Rutaceae, Lauraceae, and Lamiaceae, each with three species. Of these, the main parts used were the fruits, the leaves, and the stems (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Number of mentions of the plant parts used as food in the rural area of Linares municipality, Nuevo León, Mexico.

The most frequent forms of use of the food plants were boiled (41 %), cooked (31 %), in infusion (12 %), fried (11 %), and ground (5 %). Of the total number of species, 34 are herbaceous, 12 are shrubs, and 16 are trees. The taxa with the highest number of mentions were: Solanum tuberosum L., Lycopersicon esculentum Mill., Cucurbita pepo L., Opuntia engelmannii Salm-Dyck ex Engelm., Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill., Yucca filifera Chabaud and Dysphania ambrosioides (L.) Mosyakin & Clemants.

Quantitative ethnobotanical indexes

Medicinal

The plant species that are used and the importance of their medicinal properties for the people, determine the ethnobotanical value of the regional flora (Packer et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2020). The highest ICF values were obtained for the respiratory (0.93), genitourinary (0.91), circulatory (0.91), and digestive systems (0.90). Table 1 shows the values for the rest of the systems. These systems represent the main health issues recognized both by the World Health Organization (OMS, 2010) and in studies on traditional medicine (Singh et al., 2020; Bhat et al., 2021).

Table 1 Classification of the 11 categories of systems to obtain the ICF.

| System | Number of species mentioned (nt) |

Total number of mentions (nur) |

ICF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory | 16 | 231 | 0.93 |

| Reproductory | 8 | 84 | 0.91 |

| Circulatory | 13 | 138 | 0.91 |

| Digestive | 34 | 339 | 0.90 |

| Nervous | 13 | 118 | 0.89 |

| Sensory | 5 | 36 | 0.88 |

| Tegumentary | 16 | 125 | 0.87 |

| Muscular | 3 | 16 | 0.86 |

| Endocrine | 13 | 73 | 0.83 |

| Immunolgical | 3 | 10 | 0.77 |

| Osseous | 4 | 10 | 0.66 |

nt = Number of species mentioned; nur = Total number of mentions; ICF = Informant Consensus Factor.

The Use Value Index (UVI) is interpreted as the potential use of a particular species that is utilized to cure or counteract a specific ailment. Therefore, high values determine the frequency of medicinal species (Estrada-Castillón et al., 2021). Table 2 shows the medicinal species with the highest UVI values. According to the information provided by the respondents, a total of 13 species had a 100 % FI, indicating that they are well-known for their healing properties (Table 3). The taxa with the highest number of mentions were Turnera diffusa Willd., Artemisia ludoviciana, Cymbopogon citratus y Croton suaveolens.

Table 2 Plant species of ethnobotanical medicinal use with the highest UVI values in the rural areas of Linares, Nuevo León, Mexico.

| Scientific name | UVI | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| Dysphania ambrosioides (L.) Mosyakin & Clemants | 1 | N |

| Allium cepa L. | 1 | E |

| Allium sativum L. | 1 | E |

| Teucrium cubense Jacq. | 0.91 | N |

| Aloe vera (L.) Burm. f. | 0.91 | E |

| Mentha spicata L. | 0.88 | E |

| Moringa oleifera Lam. | 0.87 | E |

| Litsea glaucescens Kunth | 0.5 | N |

| Ruta graveolens L. | 0.46 | E |

UVI = Use Value Index; N = Native; E = Exotic.

Table 3 Species with the highest FI values (%) recorded in the rural areas of Linares municipality, Nuevo León, Mexico.

| Species | System | Ip | Iu | FI (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt. | Digestive | 49 | 49 | 100 |

| Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf | Respiratory | 49 | 49 | 100 |

| Hedeoma drummondii Benth. | Nervous | 35 | 35 | 100 |

| Hedeoma palmeri Hemsl. | Nervous | 35 | 35 | 100 |

| Croton suaveolens Torr. | Circulatory | 46 | 46 | 100 |

| Galphimia angustifolia Benth. | Urinary | 33 | 33 | 100 |

| Turnera diffusa Willd. | Reproductory | 73 | 73 | 100 |

| Allium sativum L. | Lymphatic | 4 | 4 | 100 |

| Equisetum laevigatum A. Braun | Lymphatic | 26 | 26 | 100 |

| Ocimum tenuiflorum Burm. f. | Lymphatic | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| Cannabis sativa L. | Muscular | 6 | 6 | 100 |

| Jatropha dioica Sessé ex Cerv. | Tegumentary | 26 | 26 | 100 |

| Matricaria recutita L. | Sensory | 43 | 43 | 100 |

| Cordia boissieri A. DC. | Osseous | 26 | 61 | 43 |

| Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck | Immunological | 16 | 84 | 19 |

*Ip = Number of informants who independently indicated the use of a plant for the same particular condition; **Iu = Number of informants who mentioned the species for a particular disease within a category of use. FI = Fidelity Index.

Timber

The main uses of timber species were for the construction of tools, bridges, houses, fences, furniture, fuel, and charcoal. The most important families used were Fabaceae (3 species), Pinaceae (3), Rutaceae (2), Boraginaceae (2), and Juglandaceae (2). The following taxa stand out: Ebenopsis ebano (Berland.) Barneby & J. W. Grimes, Baccharis neglecta Britton, Cordia boissieri A. DC., Ehretia anacua (Terán & Berland.) I. M. Johnst., Taxodium huegelii C. Lawson, Prosopis laevigata (Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd.) M. C. Johnst., Vachellia rigidula (Benth.) Seigler & Ebinger, V. farnesiana (L.) Wight & Arn., Havardia pallens (Benth.) Britton & Rose, Quercus polymorpha Schltdl. & Cham., Carya illinoinensis (Wangenh.) K. Koch, C. myristiciformis (F. Michx.) Nutt., Pinus teocote Schltdl. & Cham., P. cembroides Zucc., Condalia hookeri M. C. Johnst., Helietta parvifolia (A. Gray ex Hemsl.) Benth. and Zanthoxylum fagara (L.) Sarg. Of the 25 timber species, 18 are trees and eight are shrubs. The three taxa with the highest number of mentions were: Prosopis laevigata (142 mentions), Vachellia farnesiana (137 mentions) and Ebenopsis ebano (130 mentions).

Forage

29 species with ethnobotanical forage use were recorded, among which the most prominent families were Fabaceae, Poaceae, and Cactaceae. The most commonly utilized plant parts were the fruits, the leaves, and the whole plant; among of the taxa with the largest number of mentions were Rhus virens Lindh. ex A. Gray, Parthenium hysterophorus L., Cordia boissieri, Opuntia engelmannii, O. ficus-indica, Ebenopsis ebano, Eysenhardtia texana Scheele, Prosopis laevigata, Vachellia rigidula, Havardia pallens, Leucaena leucocephala (Benth.) Seigler & Ebinger, Medicago sativa L., Phaseolus vulgaris L., Vachellia constricta (Benth.) Seigler & Ebinger, Quercus polymorpha, Guilandina moringa L., Avena sativa L., Cenchrus ciliaris L., C. echinatus L., Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers., Dichanthium annulatum (Forssk.) Stapf, Hordeum vulgare L., Melinis repens (Willd.) Zizka, Panicum coloratum L., Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench, S. halepense (L.) Pers., Zea mays L. and Dioon edule Lindl.

Discussion

Both native and exotic plant species are used in the rural area of the municipality of Linares. Much the same diversity is found in nearby areas with similar vegetation, climate, and relief within the state of Nuevo León (Estrada-Castillón et al., 2014; Estrada-Castillón et al., 2017; Estrada-Castillón et al., 2021), in the northeastern area (Lara et al., 2018), and in the northern macro-region (Camou-Guerrero et al., 2008). Like in Linares, the most important families with ethnobotanical use in Oaxaca are Fabaceae, Asteraceae, Poaceae, Lamiaceae, and Cactaceae (Martínez-López et al., 2021). Regarding the uses of the plants, there are many similarities between what is recorded in Linares and what is cited for some areas of northern and southern Mexico.

Ornamental taxa play an important role in the beauty of the landscape and are relevant for the conservation of species and of the cultural heritage (Siviero et al., 2014); also, they contribute to stress reduction and improve human emotional well-being (Pauli et al., 2016). In Puebla, the main uses documented for useful flora are medicinal, nutritional, and timber (Martínez et al., 2007). In Tabasco State, Villarreal-Ibarra et al. (2014) declare the main conditions treated with plants those associated to the digestive, genitourinary, endocrine, circulatory and respiratory systems, which coincides with what was recorded in the present study. The plant parts most commonly used by the survey respondents were the leaves, the stems, and the fruits, which is also the case in Guerrero (Mendoza et al., 2020). The leaves of herbaceous plants contributed the highest percentages to the cure of ailments, in accord with the findings by Lara et al. (2018) in a research conducted in Zacatecas.

Because of its durability, the wood of Acacia farnesiana (L.) Willd., Ebenopsis ebano, Parkinsonia aculeata L. and Prosopis glandulosa Torr. is used in Linares for construction and fuel. Several taxa of Quercus, Pinus, Cupressus and Juniperus have the same use in Pakistan (Amjad y Arshad, 2014) and in Cameroon (Focho et al., 2009).

The main native and exotic food species recorded in this study are sold for the same purposes in markets in southern Mexico (Martínez et al., 2021).

The ethnobotanical indices presented relatively high values. The ICF ranged from 0.91 to 0.93, indicating that most informants use few species to cure diseases. The above coincides with the findings for the state of Hidalgo, where the values for the digestive and circulatory systems are prominent (López-Gutiérrez et al., 2014), as well as in certain areas of the state of Puebla (Vargas-Vizuet et al., 2022).

The UVI expresses the importance of a given species for all the informants interviewed, thus, if it is mentioned by many informants, it will have a high UVI. In Linares, species with a high UVI were Dysphania ambrosioides, Allium sativum L. and Aloe vera (L.) Burm. f., these have also been cited in Chiapas (Lara et al., 2019), although with lower UVI values; in Tabasco, Mentha piperita L. has been found to have a lower UVI (Gómez et al., 2016).

The FI suggests that a species has undergone selection over time; thus, a high FI value indicates a higher probability that it will prove effective. The taxa with the highest FI in Linares were Artemisia ludoviciana, Cymbopogon citratus, Hedeoma drummondii Benth., Croton torreyanus Müll. Arg., Turnera diffusa, Allium sativum and Equisetum hyemale L., several of them have been reported with high FI values in arid and semi-arid regions of Nuevo León (Estrada et al., 2015; Estrada-Castillón et al., 2017; Estrada-Castillón et al., 2021). In Morelos, Ortega-Cala et al. (2019) registers relatively high FI for Matricaria chamomilla L. (2.56), and Mentha piperita (2.56), medium FI for Psidium guajava L. (1), or low FI for Ruta gravelones L. (0.16); these species were also identified in Linares.

Conclusions

Based on the knowledge of the use of the flora in Linares, it is concluded that there is a strong cultural attachment, with many of the species playing a multifunctional role; among the ethnobotanical uses recorded are ornamental, medicinal, food, forage, and timber. This study contributes to enrich the knowledge of the ethnobotanical biocultural diversity existing in Nuevo León, in northern and northeastern Mexico. Medicinal and food plants are relevant to primary human functions, they continue to be used to cure diseases, and together with exotic species, promote cultural changes in order to meet the new health needs of local residents. As for the edible plants, many are seasonal and are used to the present day in local and regional gastronomy.

The shrub and tree flora, especially composed of native species, has various uses for timber, particularly in construction, and as a source of firewood and charcoal. In Linares, according to the respondents and to the statistical analysis conducted, traditional knowledge with its adaptations continues to prevail and to be transmitted from generation to generation, remaining relatively constant among the different age classes of the population.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the inhabitants of the various ejidos of Linares where the surveys and collection of botanical material were carried out; Jesús Alberto Cuéllar Loera, for editing the map, and the Program for the Support of Scientific and Technological Research (Programa de Apoyo a la Investigación Científica y Tecnológica, Paicyt) of the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León for the financial support provided for the present work.

REFERENCES

Albuquerque, U. P., L. V. Fernandes C. da C., R. Farias P. de L. and R. R. Nobrega A. (Edits.) 2014. Methods and Techniques in Ethnobiology and Ethnoecology. Humana Press. New York, NY, United States of America. 480 p. [ Links ]

Amjad, M. S. and M. Arshad. 2014. Ethnobotanical inventory and medicinal uses of some important woody plant species of Kotli, Azad Kashmir, Pakistan. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine 4(12):952-958. Doi: 10.12980/APJTB.4.201414B381. [ Links ]

Bhat, M. N., B. Singh, O. Surmal, B. Singh , V. Shivgotra and C. M. Musarella. 2021. Ethnobotany of the Himalayas: Safeguarding Medical Practices and Traditional Uses of Kashmir Regions. Biology 10(9):851. Doi: 10.3390/biology10090851. [ Links ]

Camou-Guerrero, A., V. Reyes-García, M. Martínez-Ramos and A. Casas. 2008. Knowledge and use value of plant species in a Rarámuri Community: A gender perspective for conservation. Human Ecology 36(2):259-272. Doi: 10.1007/s10745-007-9152-3. [ Links ]

Casas, A., A. Camou, A. Otero-Arnaíz, S. Rangel-Landa, … y E. Pérez-Negrón. 2014. Manejo tradicional de biodiversidad y ecosistemas en Mesoamérica: El Valle de Tehuacán. Investigación Ambiental 6(2):23-44. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314090302_Manejo_tradicional_de_biodiversidad_y_ecosistemas_en_Mesoamerica_el_Valle_de_Tehuacan . (26 de junio de 2022). [ Links ]

Estrada C., E., J. R. Arévalo, J. Á. Villarreal Q., M. M. Salinas R., … and C. M. Cantú A. 2015. Classification and ordination of main plant communities along an altitudinal gradient in the arid and temperate climates of northeastern Mexico. The Science of Nature 102(9-10): 59-70. Doi: 10.1007/s00114-015-1306-3. [ Links ]

Estrada, E., J. A. Villarreal, C. Cantú, I. Cabral, L. Scott and C. Yen. 2007. Ethnobotany in the Cumbres de Monterrey National Park, Nuevo León, México. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 3:8. Doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-3-8. [ Links ]

Estrada-Castillón, E., B. E. Soto-Mata, M. Garza-López, J. Á. Villarreal-Quintanilla, … and M. Cotera-Correa. 2012. Medicinal plants in the southern region of the State of Nuevo León, México. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 8:45. Doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-8-45. [ Links ]

Estrada-Castillón, E. , J. Á. Villarreal-Quintanilla, J. A. Encina-Domínguez, E. Jurado-Ybarra, … and T. V. Gutiérrez-Santillán. 2021. Ethnobotanical biocultural diversity by rural communities in the Cuatrociénegas Valley, Coahuila; Mexico. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 17:21. Doi: 10.1186/s13002-021-00445-0. [ Links ]

Estrada-Castillón, E. , J. Á. Villarreal-Quintanilla , L. G. Cuéllar-Rodríguez, M. March-Salas, … and T. V. Gutiérrez-Santillán . 2022. Ethnobotany in Iturbide, Nuevo León: The traditional knowledge on plants used in the semiarid mountains of northeastern Mexico. Sustainability 14(19):12751. Doi: 10.3390/su141912751. [ Links ]

Estrada-Castillón, E. , J. Á. Villarreal-Quintanilla , M. M. Rodríguez-Salinas, J. A. Encinas-Domínguez, … and J. R. Arévalo. 2017. Ethnobotanical survey of useful species in Bustamante, Nuevo León, Mexico. Human Ecology 46(12):117-132. Doi: 10.1007/S10745-017-9962-X. [ Links ]

Estrada-Castillón, E. , M. Garza-López , J. Á. Villarreal-Quintanilla , M. M. Salinas-Rodríguez, … and C. Cantú-Ayala. 2014. Ethnobotany in Rayones, Nuevo León, México. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 10:62. Doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-62. [ Links ]

Focho, D. A., M. C. Newu, M. G. Anjah, F. A. Nwana and F. B. Ambo. 2009. Ethnobotanical survey of trees in Fundong, northwest region, Cameroon. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 5:17. Doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-17. [ Links ]

Gómez G., E., Á. S. Sánchez, E. García L. y A. Pérez V. 2016. Valor de uso de la flora del Ejido Sinaloa 1a sección, Cárdenas, Tabasco, México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas (14):2683-2694. https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/remexca/v7nspe14/2007-0934-remexca-7-spe14-2683.pdf . (28 de junio de 2023). [ Links ]

Hammer, Ø., D. A. T. Harper and P. D. Ryan. 2001. PAST: Paleontological Statistics Software package for education and data analysis. Paleontología Electrónica 4(1):1-9. https://palaeo-electronica.org/2001_1/past/past.pdf . (19 de julio de 2022). [ Links ]

Heinrich, M., A. Ankli, B. Frei, C. Weimann and O. Sticher. 1998. Medicinal plants in Mexico: healers’ consensus and cultural importance. Social Science & Medicine 47(11):1859-1871. Doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00181-6. [ Links ]

Hurtado R., N. E., C. Rodríguez J. y A. Aguilar C. 2006. Estudio cualitativo y cuantitativo de la flora medicinal del municipio de Copándaro de Galeana, Michoacán, México. Polibotánica (22):21-50. https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/polib/n22/1405-2768-polib-22-21.pdf . (27 de junio de 2022). [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI). 1986. Síntesis geográfica del Estado de Nuevo León. INEGI. Benito Juárez, México D. F., México. 17 p. https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/productos/prod_serv/contenidos/espanol/bvinegi/productos/historicos/2104/702825220747/702825220747_1.pdf . (17 de mayo de 2022). [ Links ]

International Society of Ethnobiology (ISE). 2006. Código de Ética. ISE. Gainesville, FL, United States of America. 20 p. https://www.ethnobiology.net/wp-content/uploads/ISECodeofEthics_Spanish.pdf . (13 de noviembre de 2022). [ Links ]

Lara R., E. A., E. Fernández C., E. A. Lara R., J. M. Zepeda del V., Z. Polesny and L. Pawera. 2018. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used in Zacatecas state, Mexico. Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae 87(2):3581. Doi: 10.5586/asbp.3581. [ Links ]

Lara, E. A., E. Fernández, J. M. Zepeda-del Valle, D. J. Lara, A. Aguilar y P. Van Damme. 2019. Etnomedicina en Los Altos de Chiapas, México. Boletín Latinoamericano y del Caribe de Plantas Medicinales y Aromáticas 18(1):42-57. Doi: 10.35588/blacpma.19.18.1.04. [ Links ]

Lira, R., A. Casas and J. Blancas (Edits.). 2016. Ethnobotany of Mexico, Interactions of People and Plants in Mesoamerica. Springer. New York, NY, United States of America. 560 p. [ Links ]

López-Gutiérrez, B. N., B. E. Pérez-Escandón y M. Á. Villavicencio N. 2014. Aprovechamiento sostenible y conservación de plantas medicinales en Cantarranas, Huehuetla, Hidalgo, México, como un medio para mejorar la calidad de vida en la comunidad. Botanical Sciences 92(3):389-404. Doi: 10.17129/botsci.106. [ Links ]

Martin, G. J. 1995. Ethnobotany. A methods manual. Springer. New York, NY, United States of America. 296 p. [ Links ]

Martínez A., M. A. 1994. Estado actual de las investigaciones etnobotánicas en México. Boletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México 55:65-74. Doi: 10.17129/botsci.1450. [ Links ]

Martínez M., D., J. Reyes M., A. L. López P. y F. Basurto P. 2021. Importancia relativa de frutos y verduras comercializadas en el Mercado de Izúcar de Matamoros, Puebla, México. Polibotánica 51(26):229-248. Doi: 10.18387/polibotanica.51.15. [ Links ]

Martínez, M. Á., V. Evangelista, F. Basurto, M. Mendoza y A. Cruz-Rivas. 2007. Flora útil de los cafetales en la Sierra Norte de Puebla, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 78(1):15-40. Doi: 10.22201/ib.20078706e.2007.001.457. [ Links ]

Martínez-López, G., M. I. Palacios-Rangel, E. Guízar N. y A. Villanueva M. 2021. Usos locales y tradición: estudio etnobotánico de plantas útiles en San Pablo Cuatro Venados (Valles Centrales, Oaxaca). Polibotánica 52(26):192-212. Doi: 10.18387/polibotanica.52.13. [ Links ]

Mendoza M., A., M. Silva A. y A. E. Castro-Ramírez. 2020. Etnobotánica medicinal de comunidades Ñuu Savi de la Montaña de Guerrero, México. Revista Etnobiología 18(2):78-94. https://www.revistaetnobiologia.mx/index.php/etno/article/view/367/370 . (25 de julio de 2022). [ Links ]

New York Botanical Garden (NYBG). 2021. Index herbariorum, NYBG Steere Herbarium. https://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/ih/ . (17 de agosto de 2022). [ Links ]

Ochoa, J. J. y A. H. Ladio. 2015. Plantas silvestres con órganos subterráneos comestibles: transmisión cultural sobre recursos subutilizados en la Patagonia (Argentina). Boletín Latinoamericano y del Caribe de Plantas Medicinales y Aromáticas 14(4):287-300. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=85641104004 . (28 de junio de 2023). [ Links ]

Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). 2010. ICD-10 Version:2010 International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. https://icd.who.int/browse10/2010/en . (28 de junio de 2023). [ Links ]

Ortega-Cala, L. L., C. Monroy-Ortiz, R. Monroy-Martínez, H. Colín-Bahena, … y R. Monroy-Ortiz. 2019. Plantas medicinales utilizadas para enfermedades del sistema digestivo en Tetela del Volcán, Estado de Morelos, México. Boletín Latinoamericano y del Caribe de Plantas Medicinales y Aromáticas 18(2):106-129. Doi: 10.37360/blacpma.19.18.2.9. [ Links ]

Packer, J., G. Turpin, E. Ens, B. Venkataya, … and J. Hunter. 2019. Building partnerships for linking biomedical science with traditional knowledge of customary medicines: a case study with two Australian Indigenous communities. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 15:69. Doi: 10.1186/s13002-019-0348-6. [ Links ]

Pauli, N., L. K. Abbott, S. Negrete-Yankelevich and P. Andrés. 2016. Farmes´ knowledge and use of soil fauna in agriculture: a worldwide review. Ecology and Society 21(3):19. Doi: 10.5751/ES-08597-210319. [ Links ]

Rzedowski, J. 2006. Vegetación de México. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (Conabio). Tlalpan, México D. F., México. 505 p. https://www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/publicaciones/librosDig/pdf/VegetacionMx_Cont.pdf . (18 agosto de 2022). [ Links ]

Santos G., P. H., U. P. Albuquerque and P. Muniz de M. 2016. The most commonly available woody plant species are the most useful for human populations: a meta-analysis. Ecological Applications 26(7):2238-2253. Doi: 10.1002/eap.1364. [ Links ]

Singh, B., B. Singh , A. Kishor, S. Singh, M. N. Bhat, O. Surmal and C. M. Musarella . 2020. Exploring plant-based Ethnomedicine and cuantitative Ethnopharmacology: Medicinal plants utilized by the population of Jasrota Hill in Western Himalaya. Sustainability 12(18):7526. Doi: 10.3390/su12187526. [ Links ]

Siviero, A., T. A. Delunardo, M. Haverroth, L. C. de Oliveira, A. L. C. Roman e A. M. da Silva M. 2014. Plantas ornamentais em quintais urbanos de Rio Branco, Brasil. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Ciências Humanas 9(3):797-813. Doi: 10.1590/1981-81222014000300015. [ Links ]

Thomas, E., I. Vandebroek and P. Van Damme. 2009. Valuation of forest and plant species in indigenous territory and National Park Isiboro-Sécure, Bolivia. Economic Botany 63:229-241. Doi: 10.1007/s12231-009-9084-5. [ Links ]

Vargas-Vizuet, A. L., C. A. Lobato-Tapia, J. R. Tobar-Reyes, M. T. Solano-De la Cruz, A. Ibañez M. y A. Romero F. 2022. Plantas medicinales utilizadas en la región de Teziutlán, Puebla, México. Boletín Latinoamericano y del Caribe de Plantas Medicinales y Aromáticas 21(2):224-241. Doi: 10.37360/blacpma.22.21.2.14. [ Links ]

Villarreal Q., J. Á. y E. Estrada C. 2008. Listados Florísticos de México XXIV. Flora de Nuevo León. Instituto de Biología de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Coyoacán, México D. F., México. 153 p. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263280015_Listados_floristicos_de_Mexico_Fllora_de_Nuevo_Leon#fullTextFileContent . (19 de octubre de 2022). [ Links ]

Villarreal-Ibarra, E. C., E. García-López, P. A. López, D. J. Palma-López, … y A. Oranday-Cárdenas. 2014. Plantas útiles en la medicina tradicional de Malpasito-Huimanguillo, Tabasco, México. Polibotánica 37:109-134. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/621/62129967007.pdf . (28 de junio de 2023). [ Links ]

Zambrano-Intriago, L. F., M. P. Buenaño-Allauca, N. J. Mancera-Rodríguez y E. Jiménez-Romero. 2015. Estudio etnobotánico de plantas medicinales utilizadas por los habitantes del área rural de la Parroquia San Carlos, Quevedo, Ecuador. Universidad y Salud 17(1):97-111. http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0124-71072015000100009&lng=en&tlng=es . (15 de septiembre de 2022). [ Links ]

Zar, J. H. 2010. Biostatistical Analysis. Prentice Hall Inc. Upper Saddle River, NJ, United States of America. 944 p. [ Links ]

Received: March 09, 2023; Accepted: June 29, 2023

text in

text in