Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

Print version ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.12 n.65 México May./Jun. 2021 Epub Aug 30, 2021

https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v12i65.856

Scientific article

Allometric equations, biomass and carbon in tropical forest plantations in the coast of Jalisco

1Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias. Centro de Investigación Regional Pacífico Centro. Campo Experimental Uruapan. México.

2Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias. Centro de Investigación Regional Pacífico Centro. Campo Experimental Centro Altos de Jalisco. México.

3Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias. Centro de Investigación Regional Noreste. Campo Experimental Saltillo. México.

4Instituto de Investigaciones en Ecosistemas y Sustentabilidad. UNAM Campus Morelia. México.

Estimation of the aerial biomass is a key tool to determine the carbon stock potential of a species. Tropical-species plantations have been established in western Mexico, but their content and distribution of biomass and carbon storage are unknown. In this study, the content and distribution of aerial biomass and carbon storage of the native species Enterolobium cyclocarpum and Tabebuia rosea, and the exotic species Gmelina arborea and Tectona grandis in 12-year plantations in the state of Jalisco were estimated. Also, the relation between aerial biomass and normal diameter was adjusted with linear, potential, and polynomial models. In the four species, most of the proportion of aerial biomass (58-67 %) was found in the stem. The normal diameter was confirmed as a good predictor of total aerial biomass since two species were adjusted to potential models, and two were adjusted to polynomial models, with which it is possible to estimate aerial biomass fast, easily, and at lower cost than with the destructive method. T. grandis, G. arborea, and E. cyclocarpum were the species with the greatest biomass (161 kg ha-1, 134 kg ha-1 and 130 kg ha-1) and carbon storage potential (144.6 Mg ha-1, 120.8 Mg ha-1 and 117.5 Mg ha-1). Forest plantations with these species may contribute to long-term carbon sequestration and global warming mitigation.

Keywords: Carbon stock; biomass; normal diameter; allometric models; tropical plantations; silviculture

La estimación de la biomasa aérea es una herramienta clave para determinar el potencial de almacenamiento de carbono de un taxón. En el occidente de México, se han establecido plantaciones forestales con especies tropicales, pero se desconoce el contenido y distribución de biomasa aérea seca, así como el almacenamiento de carbono. En este estudio se estimaron estos en plantaciones de 12 años de edad con los taxa nativos: Enterolobium cyclocarpum y Tabebuia rosea, e introducidas: Gmelina arborea y Tectona grandis, ubicadas en la Costa de Jalisco. Además, se ajustaron modelos lineales, potenciales y polinomiales de la relación de la biomasa aérea seca con respecto al diámetro normal. En las cuatro especies, la mayor proporción de la biomasa aérea seca (58-67 %) se obtuvo en el fuste. El diámetro normal resultó ser un buen predictor de la biomasa aérea seca total de las especies estudiadas, de las cuales dos se ajustaron a modelos potenciales y dos a modelos polinomiales, con los cuales es posible estimar dicho atributo de forma rápida, sencilla y a menor costo en comparación al método destructivo. T. grandis, G. arborea y E. cyclocarpum presentaron tanto el contenido de biomasa más alto (161 kg ha-1, 134 kg ha-1 y 130 kg ha-1), como el mayor potencial de almacenamiento de carbono: 144.6 Mg ha-1, 120.8 Mg ha-1 y 117.5 Mg ha-1, respectivamente. Las plantaciones forestales con estas especies pueden contribuir a la captura de carbono y mitigación del calentamiento global a largo plazo.

Palabras clave: Almacén de carbono; biomasa; diámetro normal; modelos alométricos; plantaciones tropicales; silvicultura

Introduction

The establishment of forest plantations is recognized as an alternative to mitigate global warming by capturing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through photosynthesis (Raven and Karley, 2006). The carbon assimilated by the trees is stored in plant tissues, including aerial biomass (stem, branches and foliage) and belowground biomass (roots); therefore, plantations can function as carbon reservoirs for decades (Rytter, 2012).

The carbon content varies among forest species, due to different population ages, growth rates, maximum heights and thicknesses, as well as climatic and topographic conditions of the site where they grow (Casiano-Domínguez et al., 2018). Therefore, the estimation of aerial biomass has become a key procedure for assessing the capacity of forest taxa to store carbon (Soriano-Luna et al., 2015).

The use of allometric equations allows the calculation of the biomass of a forest species in a non-destructive way that can be extrapolated to similar growth situations, with relatively easy to measure parameters such as diameter and height (Montero and Montaguiri, 2005; Hernández-Ramos et al., 2017). Normal diameter is the variable that has shown the highest correlation with biomass content in various forest taxa (Rueda et al., 2014; Méndez-González et al., 2016).

Among the allometric models used to estimate biomass are linear and non-linear (exponential and polynomial) regressions (Pacheco et al., 2007; López-Reyes et al., 2016). At the local and species scale, it is essential to develop allometric models that integrate the local variability of climatic conditions, soil type, individual growth rates and forestry management (Cole and Ewel, 2006).

Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. and Tabebuia rosea (Bertol.) DC. are widely distributed in the tropical zones of Mexico, they are located in sites with secondary vegetation and are used for timber, food, fodder, ornamental and medicinal purposes (Pineda-Herrera et al., 2016; Viveros-Viveros et al., 2017). In the states of Jalisco and Michoacán, forest plantations have been established with both native and exotic taxa, such as Gmelina arborea Roxb., and Tectona grandis L. f., that have proved ample potential for establishment in commercial forestry plantations (Muñoz et al., 2009).

However, at present, the biomass content in reforestations or commercial forest plantations of these four species is unknown; thus, it is necessary to generate or adjust allometric models through easy-measure dasometric variables. The determination of biomass, in turn, would allow estimating its carbon storage potential, as an alternative to mitigate climate change. Within this context, the objectives of the present study were: 1) to estimate the aboveground dry biomass and carbon content in forest plantations of E. cyclocarpum, T. rosea, G. arborea and T. grandis; and 2) to adjust allometric equations for estimating both variables with respect to the normal diameter.

Materials and Methods

Study area

E. cyclocarpum, T. rosea, G. arborea and T. grandis forest plantations are located in La Huerta municipality, Jalisco ―which belongs to the Instituto de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP)―, at 19°31´15” N and 104°32 00” W, and at an altitude of 298 m. These are experimental monospecific 12 -year old plantations and a density of 1 111 trees ha-1 for each species and are subject to pruning. The study site has rainfall in summer, an average annual rainfall of 1 100 mm, a maximum of 34 °C, and a minimum of 12 °C; the climate corresponds to a warm sub-humid climate, and phaeozem haplic soil with a pH of 6.7 (Rueda et al., 2014).

Tree selection and felling

A total of 15 trees per species were randomly selected, including all the diameter categories present in the plantations. The height of each tree was measured with a Pm5/360pc Suunto clinometer, and the normal diameter (height at 1.30 m from the ground), with a Jackson MS Forestry Suppliers Inc. model diameter tape. Subsequently, they were felled and cut into 0.60 m long sections of the shaft, from which 5 cm thick slices were cut. The ramifications were separated from the foliage and classified as branches (diameter larger than 5 cm) and twigs (diameter of less than or equal to 5 cm). The fresh weight of each component (log, limb, branch, foliage) was determined with a 20 kg Thor clock scale. Table 1 shows the number of samples per component and total of all trees sampled per species, to determine their dry weight.

Table 1 Number of samples and distribution by structural component for four tropical forest species.

| Species | Stem | Twigs | Branches | Foliage | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. | 84 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 126 |

| Tabebuia rosea (Bertol.) DC. | 55 | 15 | 15 | 19 | 104 |

| Gmelina arborea Roxb. | 84 | 19 | 16 | 23 | 142 |

| Tectona grandis L. f. | 68 | 20 | 31 | 31 | 139 |

Sample processing

Samples of each structural component were exposed to the sun for 30 days to prevent fungal attack and rotting. Afterwards, they were placed in an ORL S-343 electric drying oven at a temperature of 70 °C for 12 days, except for the foliage, which was dried for 5 days at a temperature ranging between 35-40 °C. The weight of the dried samples was obtained with a L-Pcr-40 Torrey digital scale with accuracy in grams and with an Advance Baple-400 scale.

Determination of the dry aerial biomass per tree

The dry biomass of each structural component (stem, twigs, branches and foliage) was determined by multiplying the factor resulting from the wet weight/dry weight ratio of each sample per component. The total dry aerial biomass per tree is the sum of the dry biomass of the stem (logs) and the crown (twigs, branches and foliage). An analysis of variance (aov function) was performed to evaluate differences in aboveground dry biomass between species, as well as a Tukey's mean comparison test, both with a 95 % confidence level, with the R program, version 3.4.3 (R Core Team, 2017).

Determination of carbon per tree

The carbon content in each component was estimated by applying to the four species a carbon content percentage factor of 46.2 % for the foliage component, 46-6 % for branches and twigs, and 48.4 % for the stem, determined for T. grandis in plantations in the state of Nayarit (Ruiz et al., 2019). The total carbon content per tree was obtained from the sum of carbon in the stem, twigs, branches, and foliage of each species.

Allometric model fitting

Once the above-ground dry biomass and average carbon per tree were estimated for each species, a linear [1], potential [2] and polynomial [3] regression was performed, in which the model with the highest coefficient of determination (R2), the lowest root mean square error (RCME) and Akaike information criterion (AIC) values was chosen for each species. The fitted models are described by the equations:

Linear model:

Potential model:

Polynomial model:

Where:

B = Biomass (kg)

D = Normal diameter (cm)

a, b, c = Regression parameters

Results

Dasometric variables

The average normal diameter was statistically higher in E. cyclocarpum (gl.=3, F=9.881, P < 0.05); G. arborea and T. grandis had similar average values, while the lowest value was recorded in T. rosea. The average height also differed between species (gl.=3, F= 18.25, P < 0.05), with the highest values in T. grandis and G. arborea, and the lowest, in E. cyclocarpum. The trees of the latter species had a large diameter, but with a low height; the individuals of T. rosea were thin and low in height (Table 2).

Table 2 Normal diameter (cm) and total height (m) of four tropical species in forest plantations on the coast of Jalisco.

| Species | Normal diameter (cm) | Total height (m) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Mean | SD | |

| Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. | 21.5 | 56.8 | 33.6* | 9.2 | 7.8 | 16.5 | 11.8* | 2.3 |

| Tabebuia rosea (Bertol.) DC. | 8.2 | 29.2 | 19.3 | 6.1 | 7.9 | 16.2 | 12.7* | 2.3 |

| Gmelina arborea Roxb. | 12.8 | 35.5 | 25.4 | 6.8 | 9 | 21 | 17.1 | 3.5 |

| Tectona grandis L. f. | 14.8 | 35 | 25.3 | 6.3 | 13.7 | 20 | 17.3 | 1.9 |

Min = Minimum; Max = Maximum; Mean= Average; SD= Standard deviation; *=Statistically different species according to Tukey’s test.

Estimation of the dry aerial biomass per tree

Significant differences were obtained in the average dry aerial biomass content per tree between species (gl.= 3, F=3.382, P < 0.05). T. grandis exhibited the highest biomass, followed by G. arborea, E. cyclocarpum and T. rosea, which differed statistically compared to the others. In E. cyclocarpum, 67.2 % of biomass was found in the stem, 17.2 % in the twigs, 11.3 % in branches, and 4.3 % in the foliage; in T. rosea, 58 % corresponded to the stem, 15 % to the twigs, 17 % to branches and 10 % to the foliage. In the case of G. arborea, the distribution was 63.7 % in the stem, 17.9 % in the twigs, 11.7 % in branches, and 6.7 % in the foliage. Finally, in T. grandis, 60.7 % was registered in the stem, 14.7 % in the twigs, 18.1 % in the branches, and 6.5 % in the foliage (Table 3).

Table 3 Average aerial dry biomass per tree component of four tropical species in plantations on the coast of Jalisco.

| Species | Stem kg |

Twigs kg |

Branches kg |

Foliage kg |

Dry biomass kg tree-1 |

Standard deviation kg tree-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. | 133.5 | 50.4 | 28.9 | 8.9 | 221.0 | 160 |

| Tabebuia rosea (Bertol.) DC. | 59.0 | 19.6 | 26.9 | 10.2 | 115.8* | 144.5 |

| Gmelina arborea Roxb. | 145.3 | 41.0 | 26.8 | 14.7 | 227.9 | 66.6 |

| Tectona grandis L. f. | 165.9 | 40.3 | 49.5 | 17.5 | 273.2 | 133.3 |

*=Statistically different species according to Tukey's test.

Carbon estimate per tree

The carbon content followed the same pattern as biomass. The species with the highest record was T. grandis, followed by G. arborea and E. cyclocarpum; while T. rosea exhibited the lowest carbon value, 58 % lower than T. grandis. Table 4 shows the estimate of carbon sequestration by taxon.

Table 4 Carbon content in trees of four tropical species in plantations on the coast of Jalisco.

| Species | Minimum kg tree-1 |

Maximum kg tree1 |

Standard deviation kg tree-1 |

Average kg tree-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. | 35.3 | 325.9 | 76.5 | 105.7 |

| Tabebuia rosea (Bertol.) DC. | 6.6 | 125.2 | 31.7 | 54.9* |

| Gmelina arborea Roxb. | 24.1 | 248.9 | 69.1 | 108.7 |

| Tectona grandis L. f. | 33.4 | 229.4 | 63.6 | 130.2 |

*= Statistically different species according to Tukey's test.

Adjustment of allometric equations

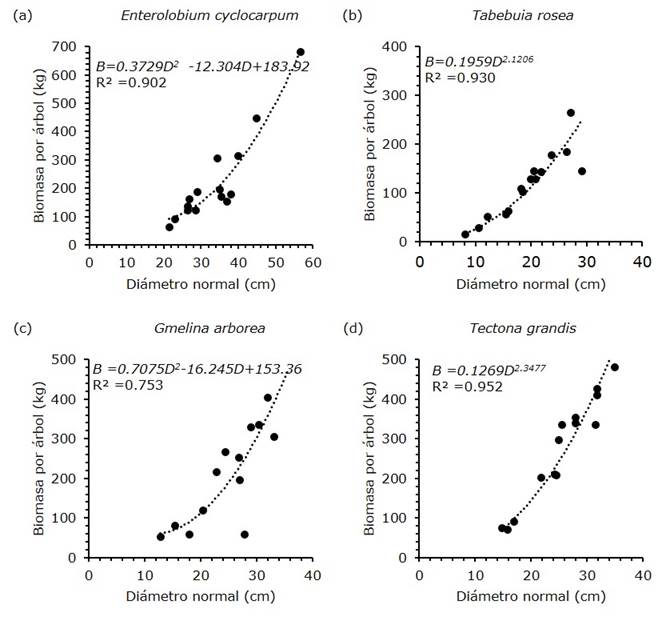

The potential model exhibited the best fit for the relationship between normal diameter and biomass of both T. rosea (R 2=0.930) and Tectona grandis (R 2=0.952), while the polynomial model fitted better for E. cyclocarpum (R 2=0.902) and G. arborea (R 2=0.753), the latter of which had the lowest coefficient of determination. The linear model was satisfactory for none of the species, since in general it had the lowest R 2 values and higher RMSE and AIC values (Table 5).

Table 5 Models for estimating the aerial dry biomass in trees of four tropical species in plantations, from normal diameter.

| Species | Model | R² | RMSE | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. | Linear | 0.837 | 62.686 | 172.712 |

| Potential | 0.898 | 49.570 | 165.670 | |

| Polynomial* | 0.902 | 48.642 | 167.102 | |

| Tabebuia rosea (Bertol.) DC. | Linear | 0.816 | 27.551 | 148.050 |

| Potential | 0.930 | 29.069 | 149.658 | |

| Polynomial* | 0.819 | 27.380 | 149.86 | |

| Gmelina arborea Roxb. | Linear | 0.705 | 75.593 | 166.840 |

| Potential | 0.658 | 69.487 | 164.482 | |

| Polynomial* | 0.753 | 69.225 | 166.376 | |

| Tectona grandis L. f. | Linear | 0.932 | 32.084 | 142.844 |

| Potential | 0.952 | 35.689 | 145.826 | |

| Polynomial* | 0.937 | 32.084 | 144.844 |

R 2 = Coefficient of determination; RMSE = Root mean square error; AIC= Akaike information criterion; * = Selected model.

Table 6 shows the equations for aboveground dry biomass and carbon content with the model selected for the best fit to the data.

Table 6 Models used to estimate carbon in aerial dry biomass of trees in forest plantations, based on normal diameter.

| Species | Type | Variable | Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. | Polynomial | Biomass | B=0.3729D 2 -12.3D+183.92 |

| Carbon | C=0.186D 2 -6.583D+101.24 | ||

| Tabebuia rosea (Bertol.) DC. | Potential | Biomass | B=0.1959D 2.1206 |

| Carbon | C=0.0904D 2.1299 | ||

| Gmelina arborea Roxb. | Polynomial | Biomass | B=0.7075D 2 -16.24D+153.36 |

| Carbon | C=0.339D 2 -7.84D+73.879 | ||

| Tectona grandis L. f. | Potential | Biomass | B=0.1269D 2.3477 |

| Carbon | C= 0.0593D 2.3536 |

B = Biomass; C = Carbon; D = Normal diameter

The relationship between normal diameter and dry aerial biomass was of potential form (Figure 1). In the case of E. cyclocarpum (Figure 1a), biomass increase accelerated from 40 cm of normal diameter onwards, a pattern that contrasted with T. rosea (Figure 1b), where the increase was slower. In the case of the introduced species (G. arborea and T. grandis), the increase in dry aerial biomass accelerated from a 20 cm normal diameter onwards (Figures 1c and 1d).

Diámetro normal = Normal diameter; Biomasa por árbol = Biomas per tree.

Figure 1 Relationship between normal diameter and dry aerial biomass in trees of Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. (a), Tabebuia rosea (Bertol.) DC. (b), Gmelina arborea Roxb. (c), and Tectona grandis L. f. (d), in plantations on the coast of Jalisco.

Determination of dry aerial biomass and carbon per hectare

Dry aerial biomass and carbon content per unit area were higher in the T. grandis plantation, followed by G. arborea, E. cyclocarpum, and T. rosea (Table 7).

Table 7 Estimation of dry aerial biomass and carbon of four tropical species in forest plantations on the coast of Jalisco.

| Species | Average biomass Mg ha-1 | Standard deviation Mg ha-1 | Average carbón Mg ha-1 | Standard deviation Mg ha-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. | 246.4 | 177.7 | 117.5 | 85.0 |

| Tabebuia rosea (Bertol.) DC. | 128.6 | 74.0 | 61.1 | 35.2 |

| Gmelina arborea Roxb. | 253.1 | 160.5 | 120.8 | 76.8 |

| Tectona grandis L. f. | 303.4 | 148.1 | 144.6 | 70.7 |

Discussion

The dry aerial biomass content was higher in the introduced species (T. grandis and G. arborea), although the native E. cyclocarpum also showed a high biomass content, which indicates that the three taxa have a great capacity for adaptation and development in the soil and climatic conditions that prevail in the tropical study area (Muñoz et al., 2009). T. rosea may have a lower growth rate due to its physiology, compared to the other taxa, at least during the first 12 years, with thin and low trees that may be related to limited nutrients or suboptimal conditions, to which it is very sensitive (Pacheco et al., 2007).

The four species assessed in this study exhibited dry aerial biomass values 90 % higher than those estimated in tropical plantations of the same age, planted with Cedrela odorata L. (34 kg tree-1) and Swietenia macrophylla King (26 kg tree-1) (Rueda et al., 2014). In addition, these records were higher than those reported for species of the mesophyll forest, such as Alnus glabrata Fernald, (48.4 kg tree-1), Quercus peduncularis Neé. (72.7 kg tree-1), and Liquidambar macrophylla Oerst. (77 kg tree-1) (Acosta-Mireles et al., 2002).

The highest proportion of the dry aerial biomass of the four taxa evaluated was determined in the stem, between 58 and 67 %, a pattern similar to that cited for C. odorata (74.7 %) and S. macrophylla (47.6 %) (Rueda et al., 2014), but lower than in Quercus laurina Humb. et. Bonpl. (83 %), Q. crassifolia Humb. et. Bonpl. (82 %), and Pinus patula Schltdl. et Cham. (89 %), mild-weather species, generally with fewer ramifications (Díaz-Franco et al., 2007; Ruiz-Aquino et al., 2014). The effect of pruning can increase the percentage of biomass in the stem and can reach up to 90 %, as was observed in T. grandis (López et al., 2018); therefore, the management of the plantations in this study may have had an effect on the distribution of biomass.

The relationship between dry aerial biomass and normal diameter was fitted to potential (T. rosea and T. grandis) and polynomial models (E. cyclocarpum and G. arborea), which is common in tropical species (Rueda et al., 2014; Aquino-Ramírez et al., 2015) and temperate species (Ruiz-Aquino et al., 2014). The first three exhibited an R 2 above 0.9, and values similar to those of the first three E. cyclocarpum (r 2= 0.96) in Tamaulipas (Foroughbakhch et al., 2006), T. grandis (r 2= 0.99) in Nayarit (Ruiz et al., 2019), and T. rosea (r 2= 0.95) in Panama (Mayoral et al., 2017). For G. arborea, was lower than that documented in plantations in Costa Rica (r 2= 0.82) (Rodríguez et al., 2018). The measurement of the normal diameter represents a reliable indicator for estimating the dry aerial biomass content and dispensing with the destructive method to obtain this information (Méndez-González et al., 2016).

The results of this study suggest that the introduced exotic species T. grandis and G. arborea have a high carbon storage potential, like E. cyclocarpum (native). The carbon stored was higher than that of tropical deciduous forest taxa (94 Mg ha-1) (Rodríguez-Laguna et al., 2008), but less than that of a coniferous forest (376 Mg ha-1) (Bolaños et al., 2017). Therefore, the establishment of commercial forestry plantations of G. arborea, T. grandis and E. cyclocarpum (also of restoration) in the tropical zone of Mexico represents an important alternative for carbon storage, thus contributing to the mitigation of global warming.

Further research on the adaptation of the introduced species to the different agro-climatic conditions and on aspects related to the detection of pests and diseases that may occur during the shift is needed.

Conclusions

Dry aerial biomass content varies among the species evaluated at 12 years. T. grandis, G. arborea and E. cyclocarpum are the best performing. The highest biomass content is found in the stem, which is characteristic of tropical and temperate climate trees. The adjusted allometric equations can be applied to similar species, especially for the estimation of carbon stocks. This study confirms that the measurement of normal diameter is an easy and reliable option for estimating aerial biomass and carbon content through polynomial and potential models. The four species are an important alternative to contribute to carbon sequestration in a significant way. It is important to research the potential for carbon storage in other tropical or temperate forest plantations in order to contribute to long-term global warming mitigation.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the staff of the Costa de Jalisco, Experimental Site of the Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP), and the Graduate Program in Biological Sciences of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

REFERENCES

Acosta-Mireles, M., J. Vargas-Hernández, A. Velázquez-Martínez y J. D. Etchevers-Barra. 2002. Estimación de la biomasa aérea mediante el uso de relaciones alométricas en seis especies arbóreas en Oaxaca, México. Agrociencia 36(6): 725-736. https://agrociencia-colpos.mx/index.php/agrociencia/article/view/225 (2 de agosto de 2020). [ Links ]

Aquino-Ramírez, M., A. Velázquez-Martínez, J. F. Castellanos-Bolaños, H. De Los Santos-Posadas y J. D. Etchevers-Barra. 2015. Partición de la biomasa aérea en tres especies arbóreas tropicales. Agrociencia 49(3): 299-314. https://agrociencia-colpos.mx/index.php/agrociencia/article/view/1148 (6 de julio de 2020). [ Links ]

Bolaños G., Y., M. A. Bolaños G., F. Paz P. y J. I. Ponce P. 2017. Estimación de carbono almacenado en bosques de oyamel y ciprés en Texcoco, Estado de México. Terra Latinoamericana 35(1): 73-86. Doi: 10.28940/terra.v35i1.243. [ Links ]

Casiano-Domínguez, M., F. Paz-Pellat, M. Rojo-Martínez, S. Covaleda-Ocon. y D. R. Aryal. 2018. El carbono de la biomasa aérea medido en cronosecuencias: primera estimación en México. Madera y Bosques 24: e2401894. Doi:10.21829/myb.2018.2401894. [ Links ]

Cole, T. G. and J. J. Ewel. 2006. Allometric equations for four valuable tropical tree species. Forest Ecology and Management 229(1-3):351-360. Doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2006.04.017. [ Links ]

Díaz-Franco, R., M. Acosta-Mireles, F. Carrillo-Anzures, E. Buendía-Rodríguez, E. Flores-Ayala y J. D. Etchevers-Barra. 2007. Determinación de ecuaciones alométricas para estimar biomasa y carbono en Pinus patula Schl. et Cham. Madera y Bosques 13(1):25-34. Doi:10.21829/myb.2007.1311233. [ Links ]

Foroughbakhch, R., M. A. Alvarado-Vázquez, J. L. Hernández-Piñero, A. Rocha-Estrada, M. A. Guzmán-Lucio and E. J. Treviño-Garza. 2006. Establishment, growth and biomass production of 10 tree Woody species introduced for reforestation and ecological restoration in northeastern Mexico. Forest Ecology and Management 235(1-3):191-201. Doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2006.08.012. [ Links ]

Hernández-Ramos, J., H. M. De los Santos-Posadas, J. R. Valdez-Lazalde, C. Tamarit-Urias, G. Ángeles-Pérez, A. Hernández-Ramos, A. Peduzzi y O. Carrero. 2017. Biomasa aérea y factores de expansión en plantaciones forestales comerciales de Eucalyptus urophylla S. T. Blake. Agrociencia 51(8):921-938. https://agrociencia-colpos.mx/index.php/agrociencia/article/view/1336 (2 de agosto de 2020). [ Links ]

López-Reyes, L. Y., M. Domínguez-Domínguez, P. Martínez-Zurimendi, J. Zavala-Cruz, A. Gómez-Guerero y S. Posada-Cruz. 2016. Carbono almacenado en la biomasa de plantaciones de hule (Hevea brasiliensis Müell. Arg.) de diferentes edades. Madera y Bosques 22(3):49-60. Doi:10.21829/myb.2016.2231456. [ Links ]

López, H. G., E. E. Vaides y A. Alvarado. 2018. Evaluación de carbono fijado en la biomasa aérea de teca en Chahal, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. Agronomía Costarricense 42(1):137-153. Doi:10.15517/RAC.V42I1.32201. [ Links ]

Mayoral, C., M. van Breugel, A. Cerezo and J. S. Hall. 2017. Survival and growth of five Neotropical timber species in monocultures and mixtures. Forest Ecology and Management 403:1-11. Doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2017.08.002. [ Links ]

Méndez-González, J., S. L. Luckie-Navarrte, M. A. Capó-Arteaga y J. A. Nájera-Luna. 2016. Ecuaciones alométricas y estimación de incrementos en biomasa aérea y carbono en una plantación mixta de Pinus devoniana Lindl. y P. pseudostrobus Lindl. en Guanajuato, México. Agrociencia 45(4):479-491. https://agrociencia-colpos.mx/index.php/agrociencia/article/view/894 (2 de agosto de 2020). [ Links ]

Montero M., M. y F. Montagnini. 2005. Modelos alométricos para la estimación de biomasa de diez especies nativas en plantaciones en la región Atlántica de Costa Rica. Recursos Naturales y Ambiente 45:112-119 Recursos Naturales y Ambiente 45:112-119 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284401254_Modelos_alometricos_para_la_estimacion_de_biomasa_de_diez_especies_nativas_en_plantaciones_en_la_region_Atlantica_de_Costa_Rica/link/59e6506caca2721fc227a595/download (16 noviembre de 2020). [ Links ]

Muñoz F., H. J., V. M. Coria Á., J. J. García S. y M. Balam C. 2009. Evaluación de una plantación de tres especies tropicales de rápido crecimiento en Nuevo Urecho, Michoacán. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 34(106):61-87. http://cienciasforestales.inifap.gob.mx/editorial/index.php/forestales/article/view/684 (5 de julio de 2020). [ Links ]

Pacheco E., F. C., A. Aldrete, A. Gómez G., A. M. Fierros G., V. M. Cetina-Alcalá y H. Vaquera H. 2007. Almacenamiento de carbono en la biomasa aérea de una plantación joven de Pinus greggii Engelm. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana 30(3):251-254. https://www.revistafitotecniamexicana.org/documentos/30-3/5a.pdf (3 de julio de 2020). [ Links ]

Pineda-Herrera, E., J. I. Valdez-Hernández y C. P. Pérez-Olvera. 2016. Crecimiento en diámetro y fenología de Tabebuia rosea (Bertol.) DC. en Costa Grande, Guerrero, México. Acta Universitaria 26(4):19-28. Doi: 10.15174/au.2016.914. [ Links ]

R Core Team. 2017. R project 4.3.4. https://www.rproject.org/ (16 de febrero de 2019). [ Links ]

Raven, J. A. and A. J. Karley. 2006. Carbon sequestration: Photosynthesis and subsequent processes. Current Biology 16(5):165-167. Doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.02.041. [ Links ]

Rodríguez-Laguna, R., J. Jiménez-Pérez, J. Meza-Rangel, O. Aguirre-Calderón y R. Razo-Zarate. 2008. Carbono contenido en un bosque tropical subcaducifolio en la reserva de la biosfera El Cielo, Tamaulipas, México. Revista Latinoamericana de Recursos Naturales 4(2):215-222. https://www.uaeh.edu.mx/investigacion/icap/LI_IntGenAmb/Rodri_Laguna/5.pdf (3 de julio de 2020). [ Links ]

Rodríguez, M., D. Arias, J. C. Valverde y D. Camacho. 2018. Ecuaciones alométricas para la estimación de la biomasa arbórea a partir de residuos de plantaciones de Gmelina arborea Roxb. y Tectona grandis L. f. en Guanacaste, Costa Rica. Revista Forestal Mesoamericana 15(1):61-68. Doi: 10.18845/rfmk.v15i1.3723. [ Links ]

Rueda S., A., A. Gallegos R., D. González E., J. A. Ruiz C., J. D. Benavides S., E. López A. y M. Acosta M. 2014. Estimación de biomasa aérea en plantaciones de Cedrela odorata L. y Swietenia macrophylla King. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 5(25):8-17. Doi: 10.29298/rmcf.v5i25.300. [ Links ]

Ruiz-Aquino, F., J. I. Valdez-Hernández, F. Manzano-Méndez, G. Rodríguez-Ortiz, A. Romero-Manzanares y M. E. Fuentes-López. 2014. Ecuaciones de biomasa aérea para Quercus laurina y Q. crassifolia en Oaxaca. Madera y Bosques 20(2):33-48. Doi: 10.21829/myb.2014.202162. [ Links ]

Ruiz B., B. A., E. Hernández Á., E. Salcedo P., R. Rodríguez M., A. Gallegos R., E. Valdés V. y R. Sánchez H. 2019. Almacenamiento de carbono y caracterización lignocelulósica de plantaciones comerciales de Tectona grandis L. f. en México. Colombia forestal 22(2):15-29. Doi: 10.14483/2256201X.13874. [ Links ]

Rytter, R. 2012. The potential of willow and poplar plantations as carbon sinks in Sweden. Biomass and Bioenergy 36:86-95. Doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2011.10.012. [ Links ]

Soriano-Luna, M. Á., G. Ángeles-Pérez, T. Martínez-Trinidad, F. O. Plascencia-Escalante y R. Razo-Zárate. 2015. Estimación de biomasa aérea por componente estructural en Zacualtipán, Hidalgo, México. Agrociencia 49(4): 423-438. https://www.colpos.mx/agrocien/Bimestral/2015/may-jun/art-6.pdf (5 de julio de 2020). [ Links ]

Viveros-Viveros, H., K. Quino-Pascual, M. V. Velasco-García, G. Sánchez-Viveros y E. Velasco B. 2017. Variación geográfica de la germinación en Enterolobium cyclocarpum en la costa de Oaxaca, México. Bosque 38(2):317-316. Doi: 10.4067/S0717-92002017000200009. [ Links ]

Received: September 12, 2020; Accepted: November 25, 2020

text in

text in