Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

Print version ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.9 n.46 México Mar./Apr. 2018

https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v9i46.115

Articles

Structure, richness and diversity of tree species in a tropical deciduous forest of Morelos

1Posgrado en Ciencias Forestales, Colegio de Postgraduados. Campus Montecillo. México.

2Centro Regional Universitario del Anáhuac, Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. México.

Because of its neighborhood to Mexico City, which is the nucleus with the largest population in the country, the state of Morelos has received considerable pressure on its forest resources; the tropical deciduous forest is one of the most impacted vegetation types. In order to know the state of conservation of this association, a study was conducted in which the structure, richness of species and diversity of tree species in the Tepalcingo municipality of said entity was described. All trees with a normal diameter ≥ 10 cm were counted in 34 sampling sites of 500 m2 with a minimum separation between them of 200 m. These sites were located using a georeferenced map, which was confirmed in the field; each of them was identified with stakes and a cross ditch in the center, to facilitate its location and subsequent remeasurement. Results indicate the presence of 883 individuals, belonging to 50 species and 20 families, of which Fabaceae stands out. The Importance Value Index (IVI), highlights as main species Lysiloma divaricatum (61.1), Amphipterygium adstringens (28.5), Conzattia multiflora (27.1), Mimosa benthami (21.5), Bursera copallifera (18.03), the index values of diversity indicate trends similar to those described for the number of species.

Key words: Biodiversity; tropical deciduous forest; Morelos State; Importance Value Index; diversity indices; Lysiloma divaricatum (Jacq.) J.F.Macbr

Por su vecindad con la Ciudad de México, que es el núcleo con mayor población del país, el estado de Morelos ha recibido una considerable presión sobre sus recursos forestales; el bosque tropical caducifolio es uno de los tipos de vegetación más impactados. A fin de conocer el estado de conservación de esta asociación, se realizó un estudio en el que se describe la estructura, riqueza y diversidad de especies de árboles en el municipio Tepalcingo de dicha entidad. Se censaron todos los árboles con un diámetro normal ≥ 10 cm en 34 sitios de muestreo de 500 m2 con una separación mínima entre ellos de 200 m, los cuales se ubicaron mediante un plano georreferenciado, que se cotejó en campo; cada uno de ellos fue identificado con estacas y una zanja en cruz en el centro, para facilitar su localización y remedición posterior. Los resultados indican la presencia de 883 individuos, pertenecientes a 50 especies y 20 familias, entre las cuales sobresale Fabaceae. Respecto al Índice de Valor de Importancia (IVI) destacan como taxa principales Lysiloma divaricatum (61.1), Amphipterygium adstringens (28.5), Conzattia multiflora (27.1), Mimosa benthami (21.5), Bursera copallifera (18.03); los valores de los índices de diversidad indican tendencias similares a las descritas para el número de especies.

Palabras clave: Biodiversidad; Bosque tropical caducifolio; estado de Morelos; Índice de Valor de Importancia; índices de diversidad; Lysiloma divaricatum (Jacq.) J.F.Macbr

Introduction

Tropical forests cover only 10 % of the Earth's surface, but they are of great global importance since they capture and process significant amounts of carbon and harbor between half and two thirds of the total species of the planet (Malhi and Grace, 2000). This vegetation located in seasonally dry tropical regions is heterogeneous and is influenced by a complex environmental and biogeographic history (Pérez et al., 2012).

Latin America is the region with the highest species richness in the world with nearly 120 thousand species of flowering plants (Zarco et al., 2010), but the one that has, in turn, the greatest intensity of destruction and from 60 to 65 % of total global deforestation (FAO, 2007).

Mexico, Brazil, Colombia and Indonesia are among the first places of species richness on the planet, which mainly gather in their tropical forests (Martínez and García, 2007); however, between 1976 and 2000 the rate of loss of these forests was 0.76 % year-1.

The state of Morelos, due to its nearness to the largest population center in the country, Mexico City, has received considerable pressure on its forest resources. Among the most impacted ecosystems are the deciduous tropical forest (BTC) and the temperate coniferous and broadleaved forest, both ecosystems with a wide territory in the country (Sagarpa, 2001).

In the southern area of the state is located the most important BTC, which includes the Sierra de Huautla Biosphere Reserve (REBIOSH), and it gathers the largest concentration of biodiversity of Morelos. Its actual condition of protected natural area does not guarantee its conservation, when it comes to areas populated by rural communities. The residents of the reserve have a close relationship with local biodiversity, and in some cases they depend directly on the environment for their survival, such as food, construction materials, medicinal plants, fuels, cultivation and grazing areas, among others. In the REBIOSH, more than 640 species of plants are used for these purposes (Conanp, 2005).

Therefore, this study aimed to describe the structure, composition and diversity of tree species in the BTC in an ejido of Morelos, Mexico. This basic information will contribute to a better understanding of the spatial and abundance patterns of vegetation for its management and conservation.

Materials and Methods

Study area

The study was carried out in the El Limón de Cuauchichinola ejido, in Tepalcingo de Hidalgo municipality, which is located in the southeast of the state of Morelos, Mexico, at 18°32' N and 98°56' W, at 1 220 m high. It has 4 236 ha, of which 1 970 ha are forested lands; It is part of the Sierra de Huautla Biosphere Reserve (Figure 1).

As it belongs to the Balsas River basin, the REBIOSH constitutes a rich reservoir of endemic Mexican species. The dominant soil types in the mountains of the reserve are Haplic phaeozem, Eutric regosol and Lithosol (INEGI, 1990). Erosion is moderate, although it tends to be severe in areas with disturbed vegetation and seasonal agriculture or on steep slopes > 15 % (Conanp, 2005).

The climatic formula Awo"(w) (i') g describes a subhumid warm climate, the driest of the subhumid, with a rainfall regime in summer, with an oscillation of the average monthly temperatures between 7 and 14 °C, and the highest temperature in May, between 26 and 27 °C (García, 2004), the precipitation of 900 mm per year, the maximum during July and September, with probable reductions or even total absence in August.

The main type of vegetation is the BTC; its main physiognomic characteristics are related to its marked climatic seasonality, which causes that most of the plant species lose their leaves for periods of five to seven months during the dry season of the year. The trees, in general, reach heights of 4 to 10 m and eventually up to 15 m (Dorado, 2001).

Sampling and measurement of variables

In order to include the greater heterogeneity of the arboreal component, 34 circular sites of 500 m2 were established and with a minimum separation between them of 200 m. These sites were initially located in a geo-referenced map, which was checked in the field through a Garmin eTrex 10 geopositioner. The sites or plots were identified with stakes and a ditch in the shape of a cross in the center, to facilitate its later location.

The trees within each of the sites ≥ 10 cm in diameter at breast height (DBH 1.30 m) were counted. To each individual was assigned a number and marked with an aluminum label, fastened with a nail, and tried to avoid damaging the trees. For each individual, their taxonomic identity was recorded and their diameter was measured with a Forestry Suppliers tape.

Vertical and horizontal structure

Height was obtained with a 5 m telescopic extension pole GEO-SURV. FGTS-5 (individuals ≤ 8 m) and a Suunto PM5/360PC clinometer (trees> 8 m). The maximum diameter (north and south) of the cup projection was also measured in each individual (Zarco et al., 2010) The horizontal structure of the forest was described from the distribution of the number of trees by diametric class; for the vertical structure of each site, frequency histograms by height category were elaborated (Zarco et al., 2010).

Importance Value Index (IVI)

This index allows to determine the dominance of the species and the degree of heterogeneity of the ecosystem. It also provides a global estimate of the importance of a species in a given community.

The IVI consists of the summation of the relative values of density, frequency and dominance. The Importance Value Index (IVI) was developed by Curtis and McIntosh (1951). It is a structural synthetic index, oriented mainly to rank the dominance of each species in mixed stands and is calculated as follows:

Relative dominance (estimator of the basimetric area) was obtained as follows:

Where:

The basimetric area (AB) of the trees through the formula:

The relative density was determined as:

Where:

The relative frequency was the result of:

Where:

Diversity

The richness of species (Dα) comes from Margalef’s index (1977), which is used to estimate the biodiversity of a community.

Where:

S = Number of species

N = Total number of individuals

As Dα has a higher value, there is a greater richness of species. Lower values than 2 are taken as zones of low biodiversity and over 5, of high biodiversity.

In order to know how homogeneous or heterogeneous were the plots (sites), the following diversity indexes were calculated (Magurran, 2004).

Shannon-Wiener (H´). This index measures the average degree of uncertainty to predict the species to which an individual taken at random within the plots belongs. This index assumes that individuals are selected at random and that all species are represented in the sample. The values that it produces are close to zero when there is only one species, and to the natural logarithm of S, when all species are represented by the same number of individuals.

Where:

S = Number of species

P i = Individuals of the i species ratio

At a higher value of H´, higher the diversity of species.

Simpson (S). It measures the probability that two individuals chosen at random in the plots belong to the same species.

Where:

n i = Number of individuals in the i eth species

N = Total number of individuals

At a higher value of S, lower the dominance of a species(s).

Diversity of Fisher. The Fisher index (Fisher et al., 1943) attempts to mitigate the problem of undervaluation or overvaluation of the previous indexes, so that one species is the intermediate result of the previous two; it calculates the Geometric Average:

Where:

S = Number of the species recorded in the sample

N = Total number of individuals in the sample = diversity index

This index could be used to compare this study with others, since it only considers the number of species (S) and the total number of individuals (N) in the samples studied (Berry, 2002); in addition, it does not depend on the size of the sampled area such as the Shannon and Simpson indexes.

Results

Structure

There were 883 individuals registered in the 34 sites (1.7 ha). No species was present in all of them, and the most frequent were Lysiloma divaricatum (Jacq.) J.F.Macbr. in 79.4 % of the sites; Conzattia multiflora (B. L. Rob.) Standl. in 70.6 %; Bursera copallifera (Sessé & Moc. ex DC.) Bullock (47.1 %); Amphipterygium adstringens (Schltdl.) Schiede ex Standl. and Malpighia mexicana A. Juss. at 44.1 %; these five species represent 10 %. A total of 35 species (70 %) appeared in five or fewer sites and 10 species (20 %) were recorded in only one. The density was 520 individuals ha-1, with 26 per site on average, with a standard deviation (SD) of ± 9, and a range of 13 to 48 (Table 1).

Table 1 Values of the structural and diversity features in 34 sites of the deciduous tropical forest at the El Limón ejido, Morelos State.

| Site | Density (individuals) | Basimetric area (m 2 ) | DBH (cm) | Height (m) | S | Shannon-Wiener (H) | Simpson D | Fisher α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22 | 0.041 | 21.5 | 10.0 | 10 | 1.9 | 5.4 | 7.1 |

| 2 | 21 | 0.045 | 21.1 | 8.4 | 7 | 1.5 | 3.8 | 3.7 |

| 3 | 23 | 0.042 | 19.7 | 9.5 | 9 | 1.7 | 4.1 | 5.4 |

| 4 | 28 | 0.019 | 14.8 | 8.3 | 11 | 2.0 | 6.1 | 6.7 |

| 5 | 16 | 0.027 | 16.9 | 7.1 | 6 | 1.5 | 4.6 | 3.5 |

| 6 | 33 | 0.025 | 17.3 | 6.2 | 7 | 1.4 | 3.0 | 2.7 |

| 7 | 26 | 0.023 | 15.8 | 4.1 | 6 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| 8 | 14 | 0.023 | 15.5 | 6.1 | 9 | 2.0 | 10.1 | 10.9 |

| 9 | 32 | 0.031 | 17.9 | 6.5 | 12 | 2.2 | 8.9 | 7.0 |

| 10 | 23 | 0.014 | 12.9 | 4.5 | 2 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.5 |

| 11 | 17 | 0.041 | 21.4 | 7.2 | 4 | 1.3 | 3.9 | 1.6 |

| 12 | 31 | 0.034 | 19.6 | 10.0 | 10 | 1.8 | 4.1 | 5.1 |

| 13 | 37 | 0.028 | 17.8 | 9.7 | 11 | 1.8 | 4.0 | 5.3 |

| 14 | 19 | 0.052 | 21.7 | 9.8 | 8 | 1.7 | 4.3 | 5.2 |

| 15 | 32 | 0.029 | 18.5 | 10.0 | 11 | 1.8 | 3.9 | 5.9 |

| 16 | 20 | 0.021 | 15.9 | 8.0 | 7 | 1.7 | 6.1 | 3.8 |

| 17 | 30 | 0.030 | 18.6 | 10.9 | 9 | 1.7 | 4.9 | 4.4 |

| 18 | 29 | 0.035 | 19.2 | 8.6 | 11 | 1.9 | 5.6 | 6.5 |

| 19 | 13 | 0.064 | 26.6 | 10.4 | 4 | 1.2 | 3.5 | 2.0 |

| 20 | 15 | 0.044 | 21.8 | 9.9 | 4 | 1.2 | 3.5 | 1.8 |

| 21 | 33 | 0.030 | 18.4 | 9.2 | 14 | 2.2 | 7.4 | 9.2 |

| 22 | 13 | 0.039 | 20.9 | 10.3 | 8 | 2.0 | 11.1 | 8.9 |

| 23 | 26 | 0.029 | 18.1 | 9.6 | 7 | 1.6 | 4.5 | 3.1 |

| 24 | 19 | 0.032 | 18.9 | 6.8 | 7 | 1.7 | 5.3 | 4.0 |

| 25 | 33 | 0.023 | 16.5 | 8.1 | 8 | 1.5 | 3.6 | 3.4 |

| 26 | 29 | 0.027 | 17.8 | 6.7 | 6 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 2.3 |

| 27 | 16 | 0.046 | 21.0 | 7.2 | 8 | 1.8 | 6.0 | 6.4 |

| 28 | 20 | 0.033 | 18.9 | 6.1 | 3 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 1.0 |

| 29 | 23 | 0.027 | 17.9 | 10.9 | 5 | 1.2 | 3.0 | 2.0 |

| 30 | 48 | 0.023 | 16.4 | 7.4 | 13 | 2.0 | 5.3 | 5.9 |

| 31 | 36 | 0.028 | 17.6 | 10.8 | 8 | 1.4 | 2.8 | 3.2 |

| 32 | 35 | 0.030 | 18.3 | 10.2 | 11 | 2.0 | 6.0 | 5.5 |

| 33 | 39 | 0.019 | 14.9 | 11.2 | 7 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 2.5 |

| 34 | 32 | 0.022 | 15.9 | 7.4 | 8 | 1.7 | 5.5 | 3.4 |

| Total | 883 | 1.075 | - | - | 50 | 2.9 | 9.02 | 11.5 |

| Mean | 26 | 0.032 | 18.4 | 8.4 | 8.0 | 1.6 | 4.7 | 4.5 |

| DE | 9 | 0.011 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 0.4 | 2.2 | 2.4 |

| CV (%) | 32.73 | 32.89 | 14.3 | 22.6 | 35.7 | 26.5 | 46.7 | 54.3 |

CV = Coefficient of variation; DN = Normal diameter; DE = Standard deviation; S = Number of species

Floristic composition

In the 34 registered sites, 50 species belonging to 36 genera and 20 families were counted. Fabaceae had the highest values by number of species (15) and individuals (517); Burseraceae occupied the second place with seven species and 88 individuals, Fabaceae together with Burseraceae, Convolvulaceae, Euphorbiaceae and Malpighiaceae, represented 60 % of the total richness obtained and 78.5 % of the number of individuals (Table 2).

Table 2 Five families with the highest values in number of species and individuals.

| Families | Species | Individuals |

|---|---|---|

| Fabaceae | 15 | 517 |

| Burseraceae | 7 | 88 |

| Convolvulaceae | 3 | 40 |

| Euphorbiaceae | 3 | 19 |

| Malpighiaceae | 2 | 29 |

| Subtotal* | 30 (60 %) | 693 (78.5 %) |

| Others(15) | 20 (40 %) | 190 (21.5 %) |

*Subtotal refers the contribution of these families as well as their percent of the total.

Vertical stratification

The average height in the total of the sites sampled in the El Limón ejido was 8.4 ± 1.9 m, with an interval of 4.1 to 11.2 m (Table 1); the species that reached greater height were Conzattia multiflora and Lysiloma acapulcensis (Kunth) Benth. (16 m), two strata were differentiated: the lower one was constituted by categories from 2 to 9 m (64.9 % of the individuals), and the superior comprised categories of 10 to 15 m (34.9 %); while only 0.2 % exceeded 15 m (Figure 2).

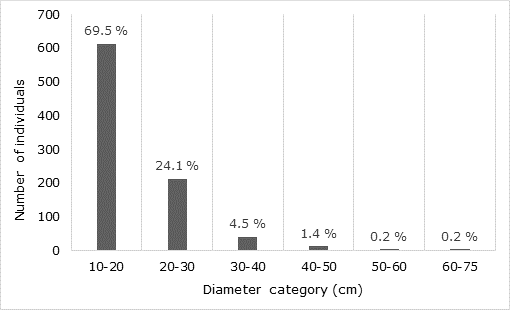

The mean DBH was 18.4 ± 2.6 cm, and the interval ranged between 10 and 74.3 cm (Table 1). The species with the most outstanding average values were Ficus cotinifolia Kunth (47.4 cm), Euphorbia fulva Stapf (37.2 cm) and Bursera schlechtendalii Engl. (29.3 cm). From 883 individuals, 93.6 % belong to the two smaller diameter categories (Figure 3).

Importance Value Index (IVI)

The five species with high IVI present in the 34 sites were, Lysiloma divaricatum, Amphipterygium adstringens, Conzattia multiflora, Mimosa benthami J.F.Macbr. and Bursera copallifera (Table 3).

Table 3 Species with the highest Importance Value Index (IVI) in the 34 sites of the El Limón ejido, Morelos State.

| Species | Dominance | Density | Frequency | IVI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABS | REL | ABS | REL | ABS | REL | |||

| 1- | Lysiloma divaricatum Jacq.) J.F.Macbr. | 6.71 | 23.44 | 245 | 27.74 | 27 | 9.96 | 61.16 |

| 2- | Amphipterygium adstringens (Schltdl.) Schiede ex Standl. | 4.15 | 14.49 | 75 | 8.49 | 15 | 5.53 | 28.52 |

| 3- | Conzattia multiflora (B. L. Rob.) Standl. | 2.93 | 10.21 | 71 | 8.04 | 24 | 8.85 | 27.11 |

| 4- | Mimosa benthami J. F. Macbr. | 2.02 | 7.06 | 89 | 10.07 | 12 | 4.42 | 21.57 |

| 5- | Bursera copallifera (Sessé & Moc. ex DC. Bullock) | 1.56 | 5.44 | 59 | 6.68 | 16 | 5.90 | 18.03 |

| Subtotal | 17.37 | 60.64 | 539 | 61.02 | 94 | 34.66 | 156.39 | |

| 45 resting species | 11.27 | 39.36 | 344 | 38.98 | 177 | 65.34 | 143.61 | |

| Total | 28.64 | 100 | 883 | 100 | 271 | 100 | 300 | |

ABS = Absolute; REL = Relative.

Diversity

The average richness in the sampled sites was 8 ± 2.9 with an interval between 2-14 species (Table 1). The Margalef index revealed a species richness of 7.2.

The total value for the Shannon-Wiener index was 2.9, the average of 1.6 ± 0.4, with values from 0.2 to 2.2 and a coefficient of variation of 26.5 %. The value of the Simpson index (9.02) and the average 4.7 ± 2.2, with a coefficient of variation of 47 %. The value obtained for the Fisher α -value was 11.5 and the average of 4.5 ± 2.4, with a variability of 54.3 % (Table 1).

Discussion

Structure

The average density for El Limón ejido is 26 individuals, which coincides with other previously documented experiences for this type of vegetation in Mexico (Trejo, 2005).

The comparison of density with other studies is limited, since they were considered other diametric categories, which depend on the objectives. In this particular work the DBH ≥ 10 cm was taken.

Floristic composition

In this study it was found that Fabaceae gathers the greatest number of species and individuals (Table 2), which agrees with descriptions of the dry forests of Mexico, Central and South America (Gillespie et al., 2000; Phillips and Miller, 2002; Trejo and Dirzo, 2002; Gallardo et al., 2005; Ruiz et al., 2005; Lott and Atkinson, 2006; Pineda et al., 2007; Pérez et al., 2010; Almazán-Núñez et al., 2012; Martínez et al., 2013). The review of Rzedowski and Calderón (2013), on the BTC, confirms the predominance of this family.

Also, Burseraceae, Convolvulaceae, Euphorbiaceae and Malpighiaceae occupy important positions for the number of species and individuals, as reported by Phillips and Miller (2002); Gallardo et al. (2005), Sousa (2010) and Almazán-Núñez et al. (2012).

It is not surprising to find that the Burseraceae family has high values in number of species and individuals (Table 2), since the Balsas basin has been recognized as a center of endemism and diversification of this taxon (De-Nova et al., 2012). It is postulated that its great diversity is due, in part, to geographic processes such as the uplift of the Western Sierra Madre and the Trans-Mexican Neovolcanic Axis, events that occurred during the Tertiary and Quaternary periods (Rzedowski et al., 2005) and that allowed its radiation, mainly along the Pacific slope and the Balsas basin.

Vertical stratification

The average tree height in the ejido was 8.44 m, which, when compared with other studies, is higher than the one obtained by Méndez et al. (2014) of 4.6 m and 4.1 m of Gallardo et al. (2005) in Cerro Verde, Oaxaca, but closer to that of 6 and 8 m recorded in different locations of Mexico and the Caribbean islands (Murphy and Lugo, 1986; Martínez et al., 1996; Salas, 2002; Segura et al., 2002; Gallardo et al., 2005; McLaren et al., 2005; Durán et al., 2006; Álvarez-Yépiz et al., 2008).

As mentioned before, heights have a direct relation with the diametric classes that were taken; Gallardo et al. (2005) included trees with diameters ≥ 5 cm and Méndez et al. (2014), ≥ 1 cm.

Importance Value Index (IVI)

The results obtained in the present study are consistent with those of Hernández et al. (2011) in three ejidos of the Sierra de Huautla, Morelos, in which Lysiloma divaricatum and Mimosa benthami registered a high IVI, which places them within the first ten species in this area. However, it is important to point out that they have taken censuses of species without considering the diameter.

Diversity

In the total sampling of the 1.7 ha, 50 species were counted from the ≥ 10 cm OF DBH tree population. The richness of species is similar to that recorded by Hernández et al. (2011), which found 54 species. Also, Méndez et al. (2014) counted 53 and 47 species, as they included all the individuals ≥ 1 and ≥ 2.5 cm of DBH, respectively; there have been results rather close in several localities of Mexico (Trejo and Dirzo, 2002; Pineda et al., 2007; Martínez et al., 2013). Richness is far from the highest values (> 100 species) documented for BTC in the Neotropics (Gentry, 1995) and worldwide (Phillips and Miller, 2002). In fact, the number of this diversity feature is more similar to those calculated by Pineda et al. (2007), Martínez et al. (2013) and to the other locations of the country studied by Trejo (2005). When compared to other sites located in America, the values of the diversity indexes (Table 1) follow trends similar to those described for the number of species.

Referencias

Almazán-Núñez, R. C., M. del C. Arizmendi, L. E. Eguiarte and P. Corcuera. 2012. Changes in composition, diversity and structure of woody plants in successional stages of tropical dry forest in southwest Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 83(4):1096-1109. [ Links ]

Álvarez-Yépiz, J. C., A. Martínez-Yrízar, A. Bórquez and C. Lindquist. 2008. Variation in vegetation structure and soil properties related to land use history of old-growth and secondary tropical dry forests in northwestern Mexico. Forest Ecology and Management 256(3):355-366. [ Links ]

Berry, P. E. 2002. Diversidad y endemismo en los bosques neotropicales de bajura. In: Guariguata, M. R. and G. H. Kattan (eds.). Ecología y Conservación de Bosques Neotropicales. Libro Universitario Regional (EULAC-GTZ). Cartago, Costa Rica. pp. 83-96. [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (Conanp). 2005 Programa de Conservación y Manejo Reserva de la Biosfera Sierra de Huautla, México. SEPRIM ed. México, D.F., México. 204 p. [ Links ]

Curtis, J. T. and R. P. McIntosh. 1951. An upland forest continuum in the prairie-forest border region of Wisconsin. Ecology 32(3):476-496. [ Links ]

De-Nova, J. A., R. Medina, J. C. Montero, A. Weeks, J. A. Rosell, M. E. Olson, L. E. Eguiarte and S. Magallón. 2012. Insights into the historical construction of species-rich Mesoamerican seasonally dry tropical forests: the diversification of Bursera (Burseraceae, Sapindales). New Phytologist 193(1):276-287. [ Links ]

Dorado R., O. R. 2001. Sierra de Huautla-Cerro Frío, Morelos: Proyecto de Reserva de la Biosfera. Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos. Centro de Investigación en Biodiversidad y Conservación. Informe final. SNIB-Conabio. Proyecto No. Q025. México D. F., México. 189 p. [ Links ]

Durán, E., J. A. Meave, E. J. Lott and G. Segura. 2006. Structure and tree diversity patterns at the landscape level in a Mexican tropical deciduous forest. Boletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México 79:43-60. [ Links ]

Fisher, R. A., A. S. Cobet and C. B. Williams. 1943. The relation between the number of species and the number of individuals in a random sample of an animal population. Journal of Animal Ecology 12(1):42-58. [ Links ]

Gallardo C., J. A., J. A. Meave y E. A. Pérez G. 2005. Estructura, composición y diversidad de la selva baja caducifolia del Cerro Verde, Nizanda (Oaxaca), México. Boletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México 76:19-35. [ Links ]

García, E. 2004. Modificaciones al Sistema de Clasificación Climática de Köppen, adaptado para las condiciones de la República Mexicana. 5ª ed. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México, D.F., México. 98 p. [ Links ]

Gentry, A. H. 1995. Diversity and floristic composition of neotropical dry forests. In: Gentry, A. H., H. A. Mooney and E. Medina (eds.). Seasonally dry tropical forests. Cambridge University Press. New York, NY, USA. pp. 146-194. [ Links ]

Gillespie, T., A. Grijalva and C. Farris. 2000. Diversity, composition, and structure of tropical dry forests in Central America. Plant Ecology 147(1):37-47. [ Links ]

Hernández S., D. A., E. Cortés D., J. L. Zaragoza R., P. A. Martínez H., G. T. González B., B. Rodríguez C. y D. A. Hernández S. 2011. Hábitat del venado cola blanca, en la Sierra de Huautla, Morelos, México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana 27(1):47-66. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI). 1990. Anuario Estadístico del Estado de Morelos. http://www.inegi.org.mx/lib/buscador/bibliotecas/busqueda.aspx?textoBus=industria&busxMetodo=1&CveBiblioteca=JEBIB&totDes=1&tipoRedIntExt=1&av=1 (8 de febrero de 2018). [ Links ]

Lott, E. J. and T. H. Atkinson. 2006. Mexican and Central American seasonally dry tropical forests: Chamela-Cuixmala, Jalisco, as a focal point for comparison. In: Pennington, R. T., G. P. Lewis and J. A. Ratters (eds.). Plant diversity, biogeography, and conservation. Taylor and Francis. Boca Raton, FL, USA. pp. 315-342. [ Links ]

Magurran, A. E. 2004. Measuring biological diversity. Blackwell, Oxford, UK. 256 p. [ Links ]

Malhi, Y. and J. Grace. 2000. Tropical forests and atmospheric carbon dioxide. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 15(8):332-337. [ Links ]

Margalef, R. 1977. Ecología. Ediciones Omega. Barcelona, España. 951 p. [ Links ]

Martínez C., J. M.,. M Méndez T., J. Cortés F., P. Coba y G. Ibarra M. 2013. Estructura y diversidad de los bosques estacionales desaparecidos por la construcción de la presa Gral. Francisco J. Múgica, en la Depresión del Balsas, Michoacán, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 84(4):1216-1234. [ Links ]

Martínez R., M. y X. García O. 2007. Sucesión ecológica y restauración de las selvas húmedas. Boletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México 80: 69-84. [ Links ]

Martínez Y., A., J. M. Maass, L. A. Pérez J. and J. Sarukhán. 1996. Net primary productivity of a tropical deciduous forest ecosystem in western Mexico. Journal of Tropical Ecology 12(1):169-175. [ Links ]

McLaren, K. P., M. A. McDonald, J. B. Hall and J. R. Healey. 2005. Predicting species response to disturbance from size class distributions of adults and saplings in a Jamaican tropical dry forest. Plant Ecology 181(1):69-84. [ Links ]

Méndez T., M., J. Martínez C., J. Cortés F., F. J. Rendón S. y G. Ibarra M. 2014. Composición, estructura y diversidad de la comunidad arbórea del bosque tropical caducifolio en Tziritzícuaro, Depresión del Balsas, Michoacán, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 85(4):1117-1128 [ Links ]

Murphy, P. G. and A. E. Lugo. 1986. Structure and biomass of a subtropical dry forest in Puerto Rico. Biotropica 18(2):89-96. [ Links ]

Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación (FAO). 2007. Situación de los bosques del mundo. Comité de Montes. Roma, Italia. 143 p. [ Links ]

Pérez G., E. A., J. A. Meave and S. R. S. Cevallos F. 2012. Flora and vegetation of the seasonally dry tropics in Mexico: origin and biogeographical implications. Acta Botánica Mexicana 100:149-193. [ Links ]

Pérez G., E. A., J. A. Meave, J. L. Villaseñor, J. A. Gallardo C. and E. E. Lebrija T. 2010. Vegetation heterogeneity and life-strategy diversity in the flora of the heterogeneous landscape of Nizanda, Oaxaca, Mexico. Folia Geobotánica 45(2):143-161. [ Links ]

Phillips, O. and J. S. Miller. 2002. Global patterns of plant diversity: Alwyn H. Gentry’s forest transect data set. Monographs in Systematic Botany from the Missouri Botanical Garden 89:1-319. [ Links ]

Pineda G., F., L. Arredondo A. y G. Ibarra M. 2007. Riqueza y diversidad de especies leñosas del bosque tropical caducifolio El Tarimo, Cuenca del Balsas, Guerrero. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 78(1):129-139. [ Links ]

Ruiz, J., M. C. Fandino and R. L. Chazdon. 2005. Vegetation structure, composition, and species richness across a 56-year chronosequence of dry tropical forest on Providencia Island, Colombia. Biotropica 37(4):520-530. [ Links ]

Rzedowski, J. y G. Calderón de R. 2013. Datos para la apreciación de la flora fanerogámica del bosque tropical caducifolio de México. Acta Botánica Mexicana 102:1-23. [ Links ]

Rzedowski, J., R. Medina L. y G. Calderón de R. 2005. Inventario del conocimiento taxonómico, así como de la diversidad y del endemismo regionales de las especies mexicanas de Bursera (Burseraceae). Acta Botánica Mexicana 70:85-111. [ Links ]

Secretaria de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación (Sagarpa). 2001. Diagnostico Forestal del Estado de Morelos. Publicación Especial No. 7. 2a Edición. Zacatepec, Mor., México. 181 p. [ Links ]

Salas M., S. H. 2002. Relaciones entre la heterogeneidad ambiental y la variabilidad estructural de las selvas tropicales secas de la costa de Oaxaca, México. Tesis de Maestría. Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México, D. F., México. 101 p. [ Links ]

Segura, G., P. Balvanera, E. Durán and A. Pérez. 2002. Tree community structure and stem mortality along a wáter availability gradient in a Mexican tropical dry forest. Plant Ecology 169(2):259-271. [ Links ]

Sousa, M. 2010. Centros de endemismo: las leguminosas. In: Ceballos, G., L. Martínez, A. García, E. Espinoza, J. Bezaury y R. Dirzo (eds.). Diversidad, amenazas y áreas prioritarias para la conservación de las selvas secas del Pacífico de México. Fondo de Cultura Económica. México, D. F., México. pp. 77-91. [ Links ]

Trejo, I. 2005. Análisis de la diversidad de la selva baja caducifolia en México. In: Halffter, G., J. Soberon, P. Koleff y A. Melic (eds.). Sobre diversidad biológica: el significado de las diversidades alfa, beta y gamma. Monografías Tercer milenio. Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa, Conabio, Grupo Diversitas, Conacyt. Zaragoza, España. pp. 111-122. [ Links ]

Trejo, I. andR. Dirzo . 2002. Floristic diversity of Mexican seasonally dry tropical forests. Biodiversity and Conservation 11(11):2063-2084. [ Links ]

Zarco E., V. M., J. I. Valdez H., G. Ángeles P. y O. Castillo A. 2010. Estructura y diversidad de la vegetación arbórea del Parque Estatal Agua Blanca, Macuspana, Tabasco. Universidad y Ciencia 26(1):1-17. [ Links ]

Received: October 18, 2017; Accepted: January 22, 2018

text in

text in