Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

Print version ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.8 n.39 México Jan./Feb. 2017

Articles

Energetic characterization of the wood of Acacia pennatula Schltdl. & Cham. and Trema micrantha (L.) Blume

1Campo Experimental San Martinito, Centro de Investigación Regional Golfo Centro, INIFAP. México. Correo-e: honorato.amador@inifap.gob.mx

Tree biomass is used primarily as solid fuel in the rural communities for purposes of cooking and heating, but it can also be used to produce fluid and gaseous fuel. Studies on the energetic properties of the wood as raw material for fuel are still limited in Mexico; therefore, the objective of the present work was to characterize the wood of Acacia pennatula and Trema micrantha energetically in terms of heat value, moisture content, basic density and proximal analysis, according to the ASTM norms. The data of the various assessments were subjected to a variance analysis, followed by a mean comparison with the t test (α = 0.05). The wood of these species showed significant differences (p < 0.05) in all the assessed energetic characteristics. In average, the wood of Acacia pennatula had a heat value of 18.54 KJ g-1 cal g-1, a moisture content of 9.15 %, a basic density of 0.571 gcm-3, 86.56 % of volatile matter, 1.07 % ashes and 12.37 % fixed carbon, while the wood of Trema micrantha had a heat value of 17.76 KJg-1, a moisture content of 8.25 %, a basic density of 0.243 g cm-3 of volatile matter, 0.79 % ashes and 16.31 % fixed carbon. The fuel value index was 10 814 for A. pennatula and 9 345 for T. micrantha. Because of its heat value and its proximal analysis, the wood of both taxa can be considered as raw material for the production of energy, although, due to its basic density, the wood of A. pennatula can be more appropriately used as fuel.

Key words: Fixed carbon; ashes; basic density; fuel value index; broadleaves; firewood

La biomasa de los árboles es utilizada, principalmente, como combustible sólido en las comunidades rurales para cocinar y calentar, pero también puede ser usada para producir combustible líquido y gaseoso. En México, los estudios de propiedades energéticas de la madera, como materia prima para combustible, aún son limitados; por lo cual, el objetivo de este trabajo fue caracterizar energéticamente la madera de Acacia pennatula y Trema micrantha en términos de su poder calorífico, contenido de humedad, densidad básica y análisis proximal, con base en las normas ASTM. A los datos de las diferentes determinaciones se les realizó un análisis de varianza, seguido de una comparación de medias con la prueba de t (α = 0.05). La madera de las especies mostró diferencias significativas (p < 0.05) en todas las características energéticas determinadas. En promedio, la de Acacia pennatula tuvo un poder calorífico de 18.54 KJ g-1 cal g-1, un contenido de humedad de 9.15 %, densidad básica de 0.571 g cm-3, 86.56 % de material volátil, 1.07 % de cenizas y 12.37 % de carbono fijo; y la madera de Trema micrantha registró un poder calorífico de 17.76 KJ g-1, un contenido de humedad de 8.25 %, densidad básica de 0.243 g cm-3, 82.90 % de material volátil, 0.79 % de cenizas y 16.31 % de carbono fijo. El índice de valor de combustible fue de 10 814 para A. pennatula y de 9 345 para T. micrantha. El valor de poder calorífico y el análisis proximal de la madera de ambos taxa permite considerlo como materia prima para la producción de energía, aunque por la densidad básica, la de A. pennatula puede ser más idónea para su uso como combustible.

Palabras clave: Carbono fijo; cenizas; densidad básica; índice de valor de combustible; latifoliadas; leña

Introduction

The energetic consumption and environmental preservation needs have led to seek sources of renewable energies. In this regard, the use of wood has gained importance at world level and has stimulated further research, as it is an essential raw material for supplying energy to many sectors in the world, including the industrial, commercial, transportation and family sectors; this last sector is particularly important in rural communities of those developing countries that use the biomass of forests as a source of energy for cooking and heating food (FAO, 2008).

The wood is used to produce various types of fuels: solid, fluid and gaseous (Trossero, 2002), and has applications in thermal (hot water or air, steam) and electric energy, the cogeneration of heat, and even mechanical energy (Nogués and Herrer, 2002).

The rational, appropriate use of wood as a source of energy must be guided by the growth and development of the species and by its energetic properties. The heat value is one of the most widely studied variables for the assessment of the energy and energetic potential of the species, primarily as firewood (Shanavas and Kumar, 2003; Nirmal et al., 2011). However, other properties --basic density, moisture contents, ashes, volatile materials and fixed carbon-- must be considered when assessing and determining the suitability of a particular wood for use as fuel (Nirmal et al., 2011; Sotelo et al., 2012). Some of these properties have been taken into account to assess the wood of the branches of a wide variety of tree and shrub taxa used as firewood in India, where most of the research on wood for household use (Chettri and Sharma, 2007; Bhatt et al., 2010; Nirmal et al., 2011; Sahoo et al., 2014; Sedai et al., 2016; Bhatt et al., 2017).

The average heat values of the wood in an anhydrous base range between 18.0 and 20.72 KJ g-1; the highest value corresponds to conifers, due to their resin content, and the lowest, to broadleaves (Vignote and Martínez, 2006).

Although the heat value in weight is higher in the wood of conifers, due to the presence of resin acids, at the volumetric level, the energy density of the biomass from highly dense broadleaves is more significant and quantitatively relevant than the registered differences in heat value, since the energy per volume unit is higher and the combustion is slower (Sotelo et al., 2012; Ortiz, 2013).

The mean heat values cited for different Acacia taxa are 19.41 ± 1.53 KJg-1, with a variation of 7.9 %. These values depend on the species, the height, the conditions for growth, the part and the position of the tree from which the sample was taken, its age and spacing (Espinoza et al.,1989; Farfán et al., 1989; Vale et al., 2000; Kataki and Konwer, 2002; Shanavas and Kumar, 2003; Quirino et al., 2004; Manrique et al., 2009; Kumar et al., 2011; Nirmal et al., 2011; Barros, S. V. dos S. et al., 2012; Agostinho-Da Silva et al., 2014; Nasser and Aref, 2014; Eloy et al., 2015; Ngangyo-Heya et al., 2016).

Wood as a source of energy, primarily as firewood or charcoal, contributes 80 % of the energy used in the rural households of Mexico (Díaz and Masera, 2003), and certain municipalities of the country have critical areas due to their firewood priority index, which relates the consumption to the availability of forest resources. In the state of Veracruz, the municipalities of Zongolica and Naranjal are a high priority, and their annual consumption of firewood from forest areas is 27.7 and 2.72 Mg year-1, respectively (Masera et al., 2004). In the Zongolica region, approximately 25 species are the most commonly used as firewood in rural areas, among which Acacia pennatula Schltdl. & Cham. and Trema micrantha (L.) Blume are prevalent (Honorato, 2010).

Despite the importance of the species used as fuel in Mexico, particularly in the Zongolica region, there is little information regarding the energetic properties of the timber used as firewood; yet, these are important for choosing the taxa that will produce the highest quality firewood. Therefore, the purpose of this work was to determine the energetic characteristics of the wood of Acacia pennatula and Trema micrantha from Zongolica and Naranjal, in the state of Veracruz, as well as to compare between the values for the two species, in order to provide technical data that may allow a better selection of the species to be used as fuel.

Materials and Methods

Five to seven branches of Acacia pennatula and Trema micrantha trees were selected. A. pennatula individuals were collected in the municipality of Zongolica, Veracruz, while T. micrantha specimens were collected in the municipalities of Zongolica and Naranjal, Veracruz. The coordinates of the collection sites are shown in Table 1.

The climate in the sampling areas of the collection sites corresponds is semi-warm humid (A) C (m, with a mean annual temperature above 18 °C, and a temperature below 18 °C during the coldest month and above 22 °C during the warmest month (Inegi, 2008); secondary tree vegetation in high deciduous rainforest (Conafor, 2014); chromic Luvisol with a fine texture as the dominant soil type at T. micrantha site 3, and fine Dystric regosol at the remaining sites (Inegi, 2014).

The selected trees had a height of 5 to 10 m and were healthy and ramified. The chosen branches were 5 to 10 cm thick. Three branches with a larger diameter were cut at a length of 1.0 m from the base and were debarked in order to obtain a cross-section at 10 cm of the ends, with which the basic density was determined using the immersion method, according to the procedures of the norm ASTM D2395 (ASTM, 2009a). The rest of the branches were planed down with a Mizutti twin-blade edger in order to obtain shavings; these were dried at room temperature (20 °C) and mixed and ground in a Thomas Wiley type mill. The ground wood was sieved using No. 40 (0.425 mm) and No.60 (0.250 MM) meshes.

The heat value was estimated using 0.9 to 1 g compressed ground wood tablets, in a pump calorimeter (Isoperibol, Parr 1266), based on the norm ASTM E71 (ASTM, 2000), and on the operation instructions of the calorimeter (Parr, 1999), at a temperature of 30 ± 0.5 °C. At the same time, the moisture content (M. C.) of the samples was registered in a previously calibrated Ohaus MB45TM moisture scale.

The ground material retained in the No. 60 mesh was used for the proximal analysis (volatile matter, ashes and fixed carbon); four repetitions were carried out per assessment for each tree. The proximal analysis was performed based on the ASTM norms: norm E871 for the moisture content (ASTM, 2012b); E872 for the volatile material (ASTM, 2012c); D102 for the ashes (ASTM, 2009b), and E870 for fixed carbon (ASTM, 2012a).

The fuel value index (FVI) was estimated using the following equation (Deka et al., 2007):

The analysis of variance was followed by a t test (α = 0.05) using the SAS software (SAS, 2000).

Results

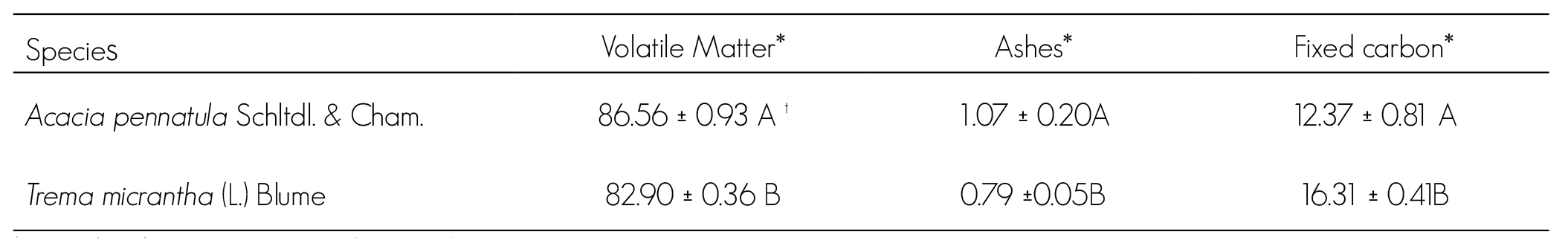

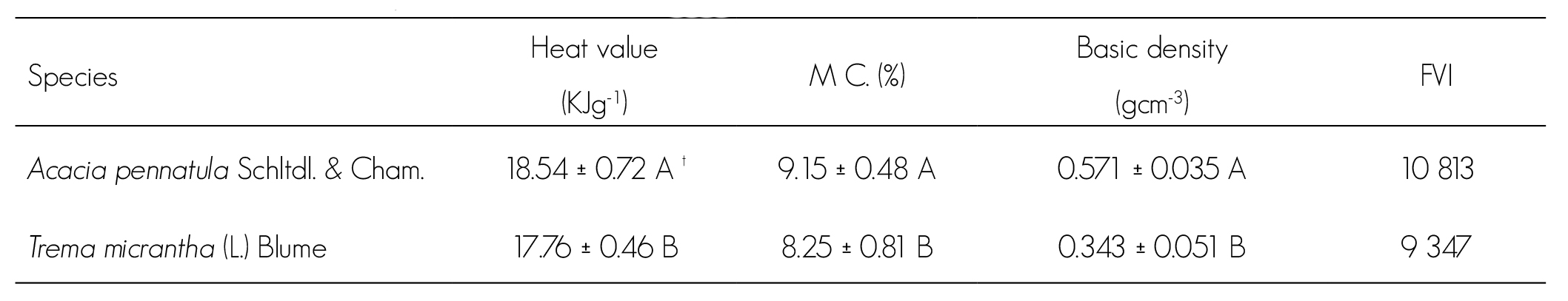

Table 2 summarizes the statistics of the analysis of variance. There were significant differences (p<0.05) for each one of the determinations for the wood of Acacia pennatula and Trema micrantha.

Table 2 Summarized variance analysis of the various determinations performed in the wood of Acacia pennatula Schltdl. & Cham. and Trema micrantha (L.) Blume.

Higher values of basic density, heat value, moisture content, FVI, volatile material and amount of ashes were found in the wood of Acacia pennatula (Tables 3 and 4). However, the wood of Trema micrantha had a higher content of fixed carbon (Table 4)

† = Values with the same latter do not differ significantly (p ≤ 0.05).

Table 3 Heat value, basic density and fuel value index of the wood

Discussion

The heat power of a material is a measure of its energetic content or the value of the heat released when the material is burnt in the air, and it is indicative of its heating potential when used as fuel (McKendry, 2002; Carbon Trust, 2009). In this work, the heat value of the wood of A. pennatula was 18.54 KJ g-1, which is higher the 17.38 KJ g-1 estimated by Farfán (1989) for branches of the same species. The value for Acacia taxa in Mexico is also higher than those obtained for the stem (17.38 KJ g-1) of Acacia cochliacantha (Farfán, 1989), as well as for the stem and branches of Acacia berlandieri (17.64 KJ g-1 and 7.22 KJ g-1) and for Acacia wrightii (17.93 KJ g-1 and 17.89 KJ g-1) (Ngangyo-Heya et al., 2016).

According to Espinoza et al. (1989), the heat value for Acacia retinoides ranges between 19.23 and 20.20 KJ g-1; these values are higher than those cited for A. pennatula. This also agrees with the values (16.92 to 26.63 KJ g-1) estimated for the wood of the stem and branches of Acacia spp. of other countries (Vale et al., 2000; Kataki and Konwer, 2002; Shanavas and Kumar, 2003; Quirino et al., 2004; Manrique et al., 2009; Kumar et al., 2011; Nirmal et al., 2011; Barros, S. V. dos S. et al., 2012; Agostinho-Da Silva et al., 2014; Nasser and Aref, 2014; Eloy et al., 2015).

Costa (2011) registers a heat value of 18.93 KJ g-1 for the wood of the stem of T. micrantha. This value is lower than the one estimated in the present study (17.76 KJ g-1); however, it is higher than 16.07 KJ g-1 and 15.45 KJ g-1, cited for the wood of the stem of the same species and of T. orientalis, respectively (Moreno and Garay, 1989; Shanavas and Kumar, 2003).

The moisture content of the wood affects the heat value negatively because of the amount of energy required to evaporate the water. The higher this amount is, the less efficient the wood is as fuel, for its net heat value decreases (Bhatt et al., 2010). In the assessment of the wood of the above species as fuel, the moisture content must not be regarded as part of the intrinsic value of a given species, because the moisture content varies according to the dimensions of the wood, the part of the tree, the season of the year and the environmental conditions (Bhatt et al., 2010; 2017).

In order to avoid the effect of moisture, in the present research the moisture content was determined in samples dried under similar conditions; however, some differences could still be observed. The moisture content of the wood of Acacia pennatula (9.15 %) was higher than that of Trema micrantha (8.25 %); this may be due to the differences in their basic density and in their anatomic structure (Rowell, 2005).

Basic density is a physical property utilized to evaluate the wood as fuel, and, along with the heat value, it determines its energetic density --a measure of the energy stored per unit of volume (Carbon Trust, 2009). Its value in the wood of Acacia pennatula, 0.571 g cm-3, was higher than the value quoted by Espinoza et al. (1989) for the stem of Acacia retinoides (0.530 g cm-3), but lower than that determined for the branches of Acacia auriculiformis (0.850 g cm-3) (Kataki and Konwer, 2002), Acacia leucophloea (0.932 g cm-3) (Nirmal et al., 2011) and 0.900-0.966g cm-3) (Kataki and Konwer, 2002; Nirmal et al., 2011). However, it is within the interval of 0.405 to 0.990 g cm-3 registered for the stem of various Acacia species (Vale et al., 2000; Shanavas and Kumar, 2003; Quirino et al., 2004; Manrique et al., 2009; Nirmal et al., 2009; Kumar et al., 2011; Barros et al., 2012; Agostinho-Da Silva, 2014; Nasser and Aref, 2014; Eloy et al., 2015).

The wood of Trema micrantha had a basic density of 0.343 g cm-3, above the value (0.239 g cm-3) registered by Moreno and Garay (1989), but lower than that (0.364 g cm-3) estimated by Costa (2011); Shanavas and Kumar (2003) also point out a value above for T. orientalis.

Different fuel value indices are used to quantify and compare between the qualities of wood as fuel (Deka et al., 2007); however, the most commonly utilized is the one indicated in the expression (1). The fuel value index (FVI) of the Acacia pennatula wood was 10 813, and that of Trema micrantha was 9 347. The estimated values are above those indicated (597-1 999) by Manrique et al. (2009) and Shanavas and Kumar (2003) for certain Acacia spp., and by Shanavas and Kumar (2003) for Trema orientalis (975). However, they are within the higher interval (5 403 - 1 596) documented for other broadleaf species (Chettri and Sharma, 2007). The differences in this index are due to the fact that it is affected by the moisture and ash contents (Deka et al., 2007).

The proximal analysis is used to characterize the biomass as fuel, and it determines the content of volatile material (VM), ashes (As) and fixed carbon (FC) expressed according to the anhydrous weight. Whenever the fresh weight is used as a reference, the moisture content is included (Jameel et al., 2010).

The volatile material of a fuel is the portion of condensable and non-condensable vapors released when the fuel is heated at a specific temperature during a given amount of time (Basu, 2013). The value for the wood of Acacia pennatula was 86.56 %, i.e. higher than that registered for A. mearnsii (75.3-82.3 %) (Agostinho-Da Silva et al., 2014; Eloy et al., 2015) and for A. auriculaeformis (81.3-84.8 %) (Kumar et al., 2011). As for the wood of Trema micrantha, no information is contained in literature. However, the estimated values are within the ranges of 79. 1 to 85.8 % registered for other broadleaves (Kumar et al., 2011; Agostinho-Da Silva et al., 2014).

Ashes are the inorganic solid residue that results from totally burning the fuel; it contains alkaline metals, silica and other inorganic materials (Basu, 2013). The ash content in the wood of Acaciapennatula(1.07%)washigherthanthe0.30-0.74%and 0.33-0.66 % registered for A. auriculaeformis and A. mearnsii, respectively (Kumar et al., 2011; Eloy et al., 2015), but lower than the value indicated for other Acacia species (Manrique et al., 2009; Agostinho-Da Silva et al., 2014; Nasser and Aref, 2014). The ash content registered for Trema micrantha was 1.92 % (Costa, 2011), and that estimated for T. orientalis was 1.20 % (Shanavas and Kumar, 2003), i.e. higher than the value determined in the present study for Trema micrantha (0.79 %).

Fixed carbon is the solid carbonaceous residue from the release of the volatile materials of the biomass; it excludes the ashes and the moisture (McKendry, 2002). The amount of fixed carbon for the wood of Acacia pennatula was 12.37 %, a lower value than those of 14.4 % cited for A. auriculaeformis (Kumar et al., 2011); of 20.9 %, for A. mangium (Barros et al., 2012), and of 16.9 to 23.2 %, for A. mearnsii (Agostinho-Da Silva et al., 2014; Eloy et al., 2015). The value of fixed carbon determined in Trema micrantha was 16.31 %; this is within the values of 13.7 to 19.7 % obtained for the wood of other broadleaves (Kumar et al., 2011; Agostinho-Da Silva et al., 2014).

Conclusions

The wood of Acacia pennatula and that of Trema micrantha differ in their energetic properties.

Due to their heat value, the contents of ashes, volatile material and fixed carbon in the wood of the studied species, these may be regarded as sources of raw materials for the obtainment of fuels. Their energetic values and the fuel value index correspond to the intervals registered by other authors for the wood of broadleaves.

Its basic density and heat value render the wood of Acacia pennatula the most appropriate for use as a domestic fuel, because it provides the largest amount of energy per cubic meter

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the Conafor-Conacyt and Conacyt-Sener-Sustentabilidad Energética Sectorial Funds for the financial support they provided to this study through projects 4201 and 151370

REFERENCES

Agostinho-Da Silva, D., B. Otomar-Caron, C. R. Sanquetta, A. Behling, D. Scmidt, R. Bamberg, E. Eloy y A. P. Dalla-Corte. 2014. Ecuaciones para estimar el poder calorífico de la madera de cuatro especies de árboles. Revista Chapingo, Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente 20(2): 177-86. [ Links ]

American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM). 2000. Standard test method for gross calorific value of refuse-derived fuel by the bomb calorimeter. ASTM E71, Annual Book of ASTM Standards, Volume 1.04. West Conshohocken, PA, USA. pp. 265-271. [ Links ]

American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM). 2009a. Standard Test Methods for specific gravity of wood and wood-Based Materials. ASMT D2395, Annual Book of ASMT Standards, Vol. 4.10. West Conshohocken, PA, USA. pp. 357-364. [ Links ]

American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM). 2009b. Standard test method for ash in wood. ASTM D102, Annual Book of ASTM Standards, Volume 04.10. West Conshohocken, PA, USA. pp. 174-175. [ Links ]

American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM). 2012a. Standard test methods for analysis of wood fuels. ASTM E870, Annual Book of ASTM Standards, Volume 1.16. West Conshohocken, PA, USA. pp. 96-97. [ Links ]

American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM). 2012b. Standard test method for moisture analysis of particulate wood fuels. ASTM E871, Annual Book of ASTM Standards, Volume 1.16. West Conshohocken, PA, USA. pp. 98-99. [ Links ]

American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM). 2012c. Standard test method for volatile matter in the analysis of particulate wood fuels. ASTM E872, Annual Book of ASTM Standards, Volume 1.16. West Conshohocken, PA, USA. pp. 100-02. [ Links ]

Barros, S. V. dos S., C. C. do Nascimento e C. P. de Azevedo. 2012. Caracterização tecnológica da madeira de três espécies florestais cultivadas no amazonas: alternativa para produção de lenha. FLORESTA 42(4): 725-732. [ Links ]

Basu, P. 2013. Biomass Gasification and Pyrolysis Practical Design and Theory. Academic Press. Burlington, MA, USA. pp. 27-63. [ Links ]

Bhatt, B. P., S. K. Sarangi and L. C. De. 2010. Fuelwood characteristics of some firewood trees and shrubs of Eastern Himalaya, India. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects 32(5): 469-474. [ Links ]

Bhatt, B. P., M. Lemtur, S. Changkija y B. Sarkar. 2017. Fuelwood characteristics of important trees and shrubs of Eastern Himalaya. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects 39(1): 47-50. [ Links ]

Carbon Trust. 2009. Biomass heating: A practical guide for potential users. In- depth guide; CTG012. The Carbon Trust. London, UK. 90 p. https:// www.carbontrust.com/media/31667/ctg012 _ biomass _ heating.pdf (28 de octubre de 2016) [ Links ]

Chettri, N. and E. Sharma. 2007. Firewood value assessment: A comparison on local preference and wood constituent properties of species from a trekking corridor, West Sikkim, India. Current Science 92(12): 1744-1747. [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional Forestal (Conafor). 2014. Carta de recursos forestales del estado de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave. Datos vectoriales escala 1:250,000. Coordinación General de Planeación e Información de la Comisión Nacional Forestal. http://187.178.171.22/OpenData/ Inventario/Carta _ Recursos _ Forestales _ 201-2012/ (2 de agosto de 2015). [ Links ]

Costa, T. G. 2011. Propriedades da madeira de espécies do cerrado mineiro e sua potencialidade para geração de energia. Dissertação de Mestrado. Universidade Federal de Lavras. Lavras, Minas Gerais, Brasil. 75 p. [ Links ]

Deka, D., P. Saikia and D. Konwer. 2007. Ranking of fuelwood species by fuel value index. Energy sources, Part A. 29:1499-1506. [ Links ]

Díaz, J. R. y O. Masera C. 2003. Uso de la leña en México: situación actual, retos y oportunidades. In: Secretaría de Energía, Subsecretaría de Política Energética y Desarrollo Tecnológico (ed.). Balance nacional de energía 2002. SENER, México, D. F., México. pp. 99-109. [ Links ]

Eloy, E., D. A. da Silva, B. Otomar C. e V. Q. de Souza. 2015. Capacidade energética da madeira e da casca de acácia-negra em diferentes espaçamentos. Pesquisa Florestal Brasileira 35(82): 163-167. [ Links ]

Espinoza, A. J., Vera, C. G., Carrillo, A. F. y C. Rodríguez F. 1989. Evaluación de plantaciones de Acacia retinoides Schlecht. con fines de producción de leña combustible In: Zavala, C. F. (comp.). Memorias de la Primera Reunión Nacional Sobre Dendroenergía. 8 y 9 de noviembre de 1989. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo, Chapingo, Edo. de Méx., México. pp. 27-39. [ Links ]

Farfán V., E., A. Sánchez V. y M. Moreno S. 1989. Estudio de cuatro especies de valor dendroenergético del Alto Balsas Poblano. In: Zavala, C. F. (comp.). Memorias de la Primera Reunión Nacional Sobre Dendroenergía. 8 y 9 de noviembre de 1989. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Chapingo, Edo. de Méx., México. pp. 391-397. [ Links ]

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2008. Bosques y energía. Cuestiones clave. Estudio FAO: Montes 154. Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación. Roma, Italia. 69 p. [ Links ]

Honorato S., J. A. 2010. Evaluación de especies nativas con fines dendroenergéticos en la Sierra de Zongolica, Veracruz. Informe Técnico Final del proyecto CONAFOR-2006-4201. INIFAP. San Martinito, Pue., México. 40 p. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (Inegi). 2008. Unidades climáticas. Conjunto de datos vectoriales, escala 1:1 000 000. http://www. inegi.org.mx/geo/contenidos/recnat/clima/ (23 de marzo de 2016). [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (Inegi). 2014. Conjunto de datos vectorial Edafológico escala 1: 250 000 Serie II (Continuo Nacional). http://www.inegi.org.mx/geo/contenidos/recnat/ edafologia/vectorial _ serieii.aspx (24 de junio de 2016). [ Links ]

Jameel, H., D. R. Keshwani, S. F. Carter and T. H. Treasure. 2010. Thermochemical conversion of biomass to power and fuels. In: Cheng, J. (ed.). Biomass to renewable energy processes. Taylor and Francis Group, LLC, Boca Raton, FL, USA. pp. 437-489. [ Links ]

Kataki, R. and D. Konwer. 2002. Fuelwood characteristics of indigenous tree species of North-East India. Biomass and Bioenergy 22: 433 - 437 [ Links ]

Kumar, R., K. K. Pandey, N. Chandrashekar and S. Mohan. 2011. Study of age and height wise variability on calorific value and other fuel properties of Eucalyptus hybrid, Acacia auriculaeformis and Casuarina equisetifolia. Biomass and Bioenergy 35: 1339-1344. [ Links ]

Manrique, S., J. Franco, V. Núñez, y L. Seghezzo. 2009. Índice de valor combustible de arbustales naturales y su potencialidad como cultivos energéticos. Avances en Energías Renovables y Medio Ambiente 13: 47-56. [ Links ]

Masera, O. R., G. Guerrero, A. Ghilardi, A. Velázquez, J. F. Mas, M. J. Ordóñez, R. Drigo and Miguel A. Trossero. 2004. Fuelwood “hot spots” in Mexico: a case study using wisdom - woodfuel integrated supply-demand overview mapping. UNAM-FAO Wood Energy Programme. Rome, Italy. 89 p. [ Links ]

McKendry, P. 2002. Energy production from biomass (part 1): overview of biomass. Bioresource Technology 83: 37-46. [ Links ]

Moreno C., A. M. y M. S. Garay M. 1989. Uso de plantas para combustible en dos comunidades nahuas: Santa Maria Cuauhtapanaloyan y Santiago Yancuictlalpan, Municipio de Cuentzalán, Puebla. In: Zavala, C. F . (comp.). Memorias de la Primera Reunión Nacional Sobre Dendroenergía. 8 y 9 de noviembre de 1989. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Chapingo, Edo. de Méx., México. pp. 8-15. [ Links ]

Nasser, R. A.-S. and I. M. Aref. 2014. Fuelwood characteristics of six acacia species growing wild in the southwest of Saudi Arabia as affected by geographical location. BioResources 9(1):1212-1224. [ Links ]

Ngangyo-Heya, M., R. Foroughbahchk-Pournavab, A. Carrillo-Parra, J. G. Rutiaga-Quiñones, V. Zelinski and L. F. Pintor-Ibarra. 2016. Calorific Value and Chemical Composition of Five Semi-Arid Mexican Tree Species. Forests 7(3): 58. doi:10.3390/f7030058. [ Links ]

Nirmal K., J. I., K. Patel, R. N. Kumar and R. Kumar B. 2009. An assessment of Indian fuelwood with regards to properties and environmental impact. Asian Journal on Energy and Environment 10(02): 99-107. [ Links ]

Nirmal, K. J. I., K. Patel, R. N. Kumar and R. Kumar B. 2011. An evaluation of fuelwood properties of some Aravally mountain tree and shrub species of Western India. Biomass and Bioenergy 35: 41-414. [ Links ]

Nogués, F. S. y J. R. Herrer. 2002. Generalidades, ciclo energías renovables, jornadas de biomasa. Fundación CIRCE. Zaragoza, España. 17 p. [ Links ]

Ortiz, T. L. 2013. Estudio de caracterización de las biomasas forestales de interés energético existentes en el sur de Galicia y norte de Portugal. Universidad de Vigo. Vigo, España.12 p. [ Links ]

Parr. 1999. 1266 Isoperibol Bomb Calorimeter. Operating Instruction Manual. Technical Note No. 367M. Parr Instrument Company. Moline, IL, USA. 1 p. [ Links ]

Quirino, W. F., A. T. Vale, A. P. A. Andrade, V. L. S. Abreu y A. C. S. Azevedo. 2004. Poder calorífico da madeira e de resíduos lignocelulósicos. Biomassa and Energia 1(2): 173-182. [ Links ]

Rowell, R. M. 2005. Moisture Properties. In: Rowell, R. M. (ed.) Handbook of wood chemistry and wood composites. CRC Press. Boca Raton, FL, USA. pp. 77-98. [ Links ]

K., J. Lalremruata and H. Lalramnghinglova. 2014. Assessment of fuelwood based on community preference and wood constituent properties of tree species in Mizoram, North-East India. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods 23(4): 280-288. [ Links ]

Statistical Analysis System (SAS). 2000. The SAS system for windows (Version 8.0 for Windows). SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC. USA. n/p. [ Links ]

Sedai, P., D. Kalita and D. Deka. 2016. Assessment of the fuel wood of India: A case study based on fuel characteristics of some indigenous species of Arunachal Pradesh. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects 38(7): 891-897. [ Links ]

Shanavas, A. and B. M. Kumar. 2003. Fuelwood characteristics of tree species in homegardens of Kerala, India. Agroforestry Systems 58: 1-24. [ Links ]

Sotelo M., C., J. C. Weber, D. A. Silva, C. Andrade, G. I. B. Muñiz, R. A. Garcia and A. Kalinganire. 2012. Effects of region, soil, land use, and terrain type on fuelwood properties of five tree/shrub species in the Sahelian and Sudanian ecozones of Mali. Annals of Forest Science 69: 747-756. [ Links ]

Trossero, M. A. 2002. Dendroenergía: perspectivas de futuro. Unasylva 21(53): 3-12. [ Links ]

Vale, A. T., M. A. M. Brasil., C. M. Carvalho y R. A. A. Veiga, 2000. Produção de energia do fuste de Eucalyptus grandis Hill Ex-Maiden e Acacia mangium Willd em diferentes níveis de adubação. CERNE 6(1): 83-88. [ Links ]

Vignote, P. S. y R. I. Martínez. 2006. Tecnología de la madera. Ediciones Mundi-Presa. 3a Ed. Madrid, España. 678 p [ Links ]

Received: October 14, 2015; Accepted: December 10, 2016

text in

text in