Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

Print version ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.7 n.34 México Mar./Apr. 2016

Article

Potential distribution of Prosopis laevigata (Humb. et Bonpl. ex Willd) M. C. Johnston based on an ecological niche modelc d

1 Instituto de Ciencias Básicas e Ingenierías. Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo.

2Instituto de Ciencias Agropecuarias. Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo.

Prosopis laevigata is a widely distributed species in arid zones of northern and central Mexico. It is very useful from the environmental point of view, as it prevents desertification and erosion processes due to its high soil-holding capacity, as well as its capacity to improve fertility and to stabilize salinity levels. It is a source of food and provides shelter to wildlife; furthermore, various goods for consumption by human beings are produced from this species, so it has been overexploited for decades in Mexico. Therefore, it has become necessary to determine potential areas for its establishment. For this purpose, the potential distribution of this species in three physiographic provinces was studied. Spatial data on sightings recorded in the World Network of Information on Biodiversity (REMIB, for its acronym in Spanish), and with the BIOCLIM ecological niche model were selected and applied with the DIVA-GIS 7.5 software. They were validated with an analysis of the area under the ROC curve and using the Kappa estimator. The results suggest that P. laevigata can grow optimally in 15 % of the provinces (70 632.08 km2), and that the most limiting factors it faces are the seasonality of precipitation (9.25 %) and the temperature (11.43 %). Both the ROC analysis and Kappa indicate that the utilized model has an excellent performance and a high probability of accuracy (ROC = 0.973; Kappa = 0.915); therefore, these formulas are adequate to determine potential areas for the development of this species.

Key words: BIOCLIM; spatial distribution; mesquite; ecological niche; Prosopis laevigata (Humb. et Bonpl. ex Willd) M. C. Johnston; reforestation

Prosopis laevigata es una especie con amplia distribución en zonas áridas del norte y centro de México; desde el punto de vista ambiental es muy útil pues previene los procesos de desertificación y erosión por su alta capacidad de retención del suelo, de mejoramiento de la fertilidad y de estabilizar la salinidad. Es fuente de alimento y refugio para la fauna silvestre y produce diversos bienes para el ser humano, por lo que ha sido sobreexplotada desde hace décadas en el país; por lo tanto, es ya necesario determinar zonas potenciales para su establecimiento. Para ello, se trabajó con la distribución potencial de esta especie en tres provincias fisiográficas. Se recabaron datos espaciales de avistamientos registrados en la Red Mundial de Información sobre Biodiversidad (REMIB) y se seleccionó el modelo de nicho ecológico BIOCLIM, que fue aplicado en el programa DIVA-GIS ver. 7.5. Se le validó con un análisis de área bajo la curva (ROC) y el estimador Kappa. Los resultados sugieren que P. laevigata puede crecer de manera óptima en 15 % de las provincias (70 632.08 km2) y los factores más limitantes que enfrenta son la estacionalidad de precipitación (9.25 %) y la temperatura (11.43 %). Los análisis ROC y Kappa indican que el modelo utilizado tiene un excelente desempeño y una alta probabilidad de acierto (ROC = 0.973; Kappa = 0.915), por lo que estas fórmulas son adecuadas para determinar áreas potenciales para el desarrollo de la especie.

Palabras clave: BIOCLIM; distribución espacial; mezquite; nicho ecológico; Prosopis laevigata (Humb. et Bonpl. ex Willd) M. C. Johnston; reforestación

Introduction

At word level, there is a concern due to the changes that are being produced in the structure and vegetal composition of ecosystems as a result of anthropic activities (FAO, 2011). Furthermore, the overexploitation and misuse of forest ecosystems is causing a loss of quality in such environmental services as the setting of limits to greenhouse gas emissions, the reduction of the water quality, soil erosion and desertification, among other things that put at risk the livelihood and cultural integrity of those populations that depend directly on forests (López, 2012).

A reduction of 155 thousand has of forests and rainforests is estimated to occur in Mexico every year (UANL, 2009a). If reduction of these ecosystems continues at the same rate, by 2050 all of the forest areas will have been eliminated (Cortesi, 2002). Several programs are in place to prevent this scenario (Semarnat, 2004; UANL, 2009b; UACh, 2010).

A valuable tool utilized in research on biological conservation is the estimation of the potential species distribution areas in order to establish forest plantations (Austin, 2007; Soberón and Nakamura, 2009).

The spatial distribution of species depends on their ecological amplitude (tolerance to environmental factors like temperature, precipitation, humidity, topographic position and altitude) (Finch et al., 2006). Based on this amplitude, it is possible to measure the probability of their presence in a specific geographical space (Plamen and Stoyanov, 2005).

Certain analysis methods allow determining distribution areas of species of environmental interest (Hijmans et al., 2005). These predictive models simplify the concept of ecological niche by taking into account environmental factors of the harvest locations of the species in order to reproduce it (Finch et al., 2006).

Prosopis laevigata Humb. et Bonpl. ex Willd) M. C. Johnston is an arboreal species with a wide distribution in arid and semi-arid areas of the north and center of Mexico (Villanueva et al., 2004). Its roots may be over 50 m deep and extend laterally up to 15 m (Ríos et al., 201). It works as a source of food and provides shelter for wildlife. Human communities have used it both as food and as fuel. From the environmental point of view, it is a very useful species because it prevents desertification and erosion processes due to its high soil-holding capacity and because it improves fertility and helps stabilize salinity levels (Rodríguez et al., 2014).

As a result of the exploitation to which this species has been subjected through the years due to the large variety of its current and potential uses, this species presents a reduction rate in its surface area in several states of the Mexican Republic, which is particularly notorious in the states of Coahuila (5 054 ha-1 year), Durango (500 ha-1 year) and Chihuahua (340 ha-1 year) (Ríos et al., 2011). In order to counteract this, proposals are being made to establish plantations of this species, for which there is a risk of failure at the site of final residence of the plants (Reséndez et al., 2013). It is therefore necessary to determine places where favorable climatic conditions prevail.

Materials and Methods

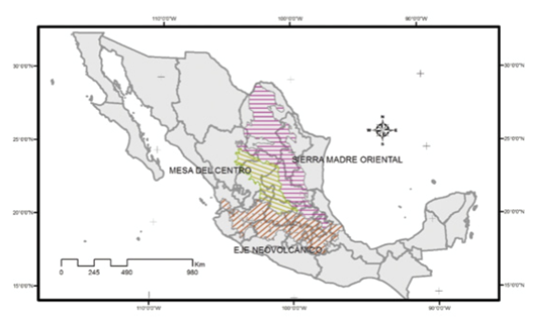

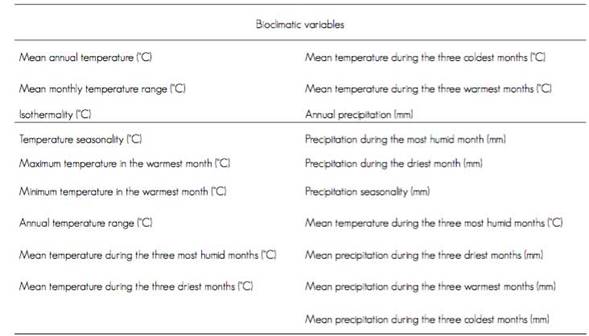

The potential distribution of P. laevigata in three physiographic provinces of the Mexican republic (Figure 1) was determined using the BIOCLIM algorithm with the DIVA GIS 7.5 software (Higmans et al., 2012), which generate an ecological interval for the species according to the predictive variables, by means of an analysis of the distribution of records of presence for each environmental variable. Locations of the species were included in the model as georeferenced input data obtained from the World Network of Information on Biodiversity (REMIB, for its acronym in Spanish), an interinstitutional network sharing biological information and consisting of research centers that host scientific collections around the world. Also added were several layers of climatic variables taken from the WorldClim’s climate database for the years 1950-2000, at a 2.5 minute resolution (Table 1).

The output data of the classic BIOCLIM model and the more limiting BIOCLIM factor were utilized to define the potential distribution and the main climatic variables associated with the species. They were validated by means of an analysis of the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (ROC AUC) and an estimation using the Kappa algorithm (López and Fernández, 1998).

These analyses are tests frequently used in potential distribution models to show the discrimination capacity of the model; the closer to 1 the results are, the more accurate the model (Anderson, 2003; García, 2008). The output data were mapped in an ASCIIGRID file, and the percentages of optimal area and the surface area (km2) of the physiographic provinces were determined using the ArcGis 10 software.

Results and Discussion

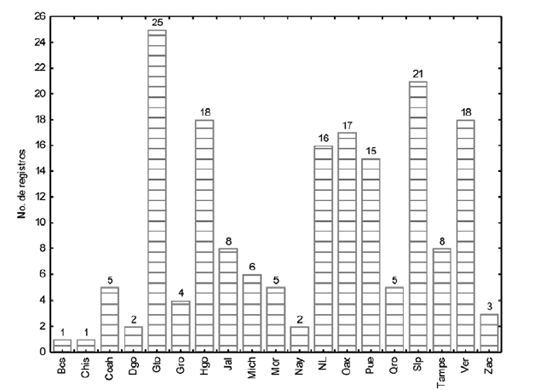

Prosopis laevigata has a wide natural distribution in Mexico (Figure 2). It has been identified in various states, including Guanajuato, Hidalgo, Nuevo León, Oaxaca, Puebla, San Luis Potosí and Veracruz, which stand out for having the highest records for this species (Figure 3).

Figure 3 States with the highest number of georeferenced records for Prosopis laevigata (Humb. et Bonpl. ex Willd) M. C. Johnston in Mexico.

The wide geographical distribution of P. laevigata indicates that this species can be established in areas with varying temperature and humidity levels, as referred by Rzedowski (1988), who recognizes the presence of Prosopis in many regions of the American continent, particularly in arid and semi-arid zones (Table 2).

Table 2 Bioclimatic intervals in the areas in which the presence of Prosopis laevigata (Humb. et Bonpl. ex Willd) M. C. Johnston has been recorded.

T. = Temperature; PP = Pluvial precipitation.

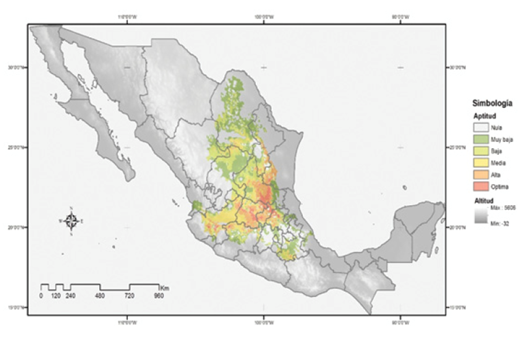

The final potential distribution map for mesquite shows-in red-the areas where the species can be optimally established; these are concentrated mostly in central Mexico, a region that includes the states with the highest records. Similar locations exist to the west of the Transversal Neovolcanic Axis, as well as to the east of the Eastern Sierra Madre (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Potential distribution of Prosopis laevigata (Humb. et Bonpl. ex Willd) M. C. Johnston in Mexico.

These results confirm the findings of Gómez et al. (2008), as they all recognize the same areas of Nuevo León and Tamaulipas as appropriate for Prosopis laevigata. Likewise, similarities are found in the eastern region of the Transversal Volcanic System, considered to be moderately suitable, and in the eastern and central zones, regarded as unsuitable; this coincides with the results obtained using the BIOCLIM algorithm. Nevertheless, there are disagreements as to the optimal zone, as, according to the model of the said authors, the territories with this condition are much more limited and are located mainly in the Eastern Sierra Madre and in the Western Sierra Madre. This disparity may be due to the fact that the sampling points of central Mexico were omitted from that research, and therefore it was impossible to correctly determine the location based on the model.

The results obtained with BIOCLIM agree with those reported by Guevara et al. (2008), according to whom P. laevigata is identified as a species that thrives in arid and semi-arid zones; however, its ecological affinities are not a uniform entity and may even be more specific than those of other bush species-a fact that accounts for its limited optimal potential distribution.

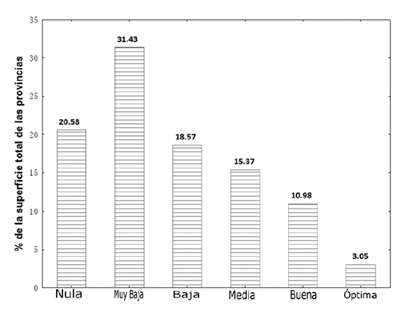

According to the model, 15 % of the territory of the three physiographic provinces is suitable for the establishment of this species (Figure 5) and is equivalent to 70 632.08 km2, distributed mainly in the states of Guanajuato, Hidalgo, Jalisco, Michoacán, Querétaro, San Luis Potosí and Tamaulipas.

When comparing the degrees of suitability by state, we observe that Nuevo León and Puebla possess only one good condition for the species; yet, this is not optimal as in the case of Guanajuato and San Luis Potosí, which have the largest surface area with the bioclimatic requirements of mesquite; this agrees with the results of comparing the georeferenced records of REMIB (Figure 6).

Gto. = Guanajuato; Hgo. = Hidalgo; Jal. = Jalisco; Mich. = Michoacán; NL. = Nuevo León; Pue. = Puebla; Qro. = Querétaro; SLP. = San Luis Potosí; Tamps. = Tamaulipas.

Figure 6 Surface area, in km2, with good and optimal suitability for the establishment of Prosopis laevigata (Humb. et Bonpl. ex Willd) M. C. Johnston.

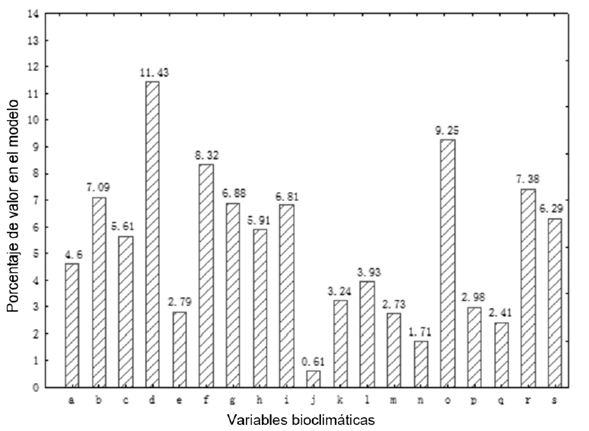

According to the model, the factors that had an impact on the establishment of the species were temperature and precipitation seasonality (1.43 % and 9.25 %, respectively), which implies that P. laevigata is mainly affected by the monthly differences in these variables (Figure 7); these results agree with the findings of Ávila et al. (2014) for wide distribution species, which confirm this assumption.

a = Annual temperature; b = Monthly temperature interval; c = Isothermality; d = Temperature seasonality; e = Maximum temperature during the warmest month; f = Minimal temperature during the warmest month; g = Annual temperature interval; h = Temperature in the most humid quartile; i = Temperature in the driest quartile; j = Temperature in the coldest quartile; k = Temperature in the warmest quartile; l = Annual pluvial precipitation; m = Pluvial precipitation during the most humid month; n = Pluvial precipitation during the driest month; o = Pluvial precipitation seasonality; p = Pluvial precipitation in the most humid quartile; q = Pluvial precipitation in the driest quartile; r = Pluvial precipitation in the warmest quartile; s = Pluvial precipitation in the coldest quartile.

Figure 7 The most limiting factors in the ecological niche model.

The analysis of the area under the ROC curve and using the Kappa estimator yielded results of 0.973 and 0.915. Consequently, it is inferred that the model has an excellent predictive capacity, for if the result for both estimators is closer to 1, the model will have a higher probability of accuracy, and therefore give better predictions for the areas (Figure 8)- an indication of its excellent performance. This behavior has been verified by Ávila et al. (2014) and Contreras et al. (2010), who registered AUC values of 0.997 and 0.971 for Taxus globosa Schltdl. and Pinus herrerae Martínez, respectively; in both cases, the authors concluded that they had obtained accurate results.

Conclusions

The Transversal Neovolcanic Axis region, the Southern High Plateau and the Eastern Sierra Madre all cover a surface area of 70 632.08 km2, in which the temperature and pluvial precipitation seasonality are the most limiting factors (1.43 % and 9.25 %, respectively) for the optimal development of Prosopis laevigata.

This type of studies allows the definition of better parameters for the development of management plans and plantations of this species, as it helps to identify the potential areas for the establishment of the species, and thus, to ensure a high survival rate.

REFERENCES

Anderson, R. P., D. Lew and P. Townsend. 2003. Evaluating predictive models of species’ distributions: criteria for selecting optimal models. Ecological Modelling 162 (3): 21-232. [ Links ]

Austin, M. P. 2007. Species distribution models and ecological theory: A critical assessment and some possible new approaches. Ecological Modelling 200 (1-2):1-19. [ Links ]

Ávila, R., R. Villavicencio y J. A. Ruíz. 2014. Distribución potencial de Pinus herrerae Martínez en el occidente del estado de Jalisco. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 5 (24): 92-109. [ Links ]

Contreras, M. R., V. I. Luna y M. C. A. Ríos. 2010. Distribución de Taxus globosa (Taxaceae) en México: modelos ecológicos de nicho, efectos del cambio del uso de suelo y conservación. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 83: 421-433. [ Links ]

Cortesi, A. 2002. La pérdida de biodiversidad en nuestro mundo. In: Conferencia Anual de la The World Future Society. Philadelphia, PA, USA. 8 p. [ Links ]

Villanueva D., J., R. J. Ibarra, E. H. Cornejo O. y C. Potisenek T. 2004. El mezquite en la Comarca Lagunera. Su dinámica, volumen maderable y tasas de crecimiento anual. Agrofaz 4 (2): 633-648. [ Links ]

Finch, J. M., M. J. Samways, T. R. Hill, S. E. Piper and S. Taylor. 2006. Application of predictive distribution modelling to invertebrates: Odonata in South Africa. Biodiversity and Conservation 15 (13): 4239-4251. [ Links ]

García M., M. R. 2008. Modelos predictivos de riqueza de diversidad vegetal. Comparación y optimización de métodos de modelado ecológico. Tesis Doctoral. Departamento de Biología Vegetal I. Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Madrid, España 186 p. [ Links ]

Gómez D., J. D., A. I. Monterroso R., J. A. Tinoco R. y M. L. Toledo M. 2008. Impactos del cambio climático en el sector forestal a nivel país. Instituto Nacional de Ecología. México, D. F., México. 93 p. [ Links ]

Guevara E., A., E. González S., H. Suzán A., G. Malda B., M. Martínez D., M. Gómez S., L. Hernández S., Y. Pantoja H. y D. Olvera V. 2008. Distribución potencial de algunas leguminosas arbustivas en el altiplano central de México. Agrociencia 42 (6): 703-716. [ Links ]

Hijmans, R. J., S. E. Cameron, J. L. Parra, P. G. Jones and A. Jarvis. 2005. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology 25(15): 1965-1978. DOI: 10.1002/joc.1276. [ Links ]

Hijmans, R. J., L. Guarino and P. Mathur. 2012. DIVA-GIS Version 7.5 Manual. 71 p. http://www.diva-gis.org/docs/DIVA-GIS_manual_7.pdf (12 de julio de 2013). [ Links ]

López, A. 2012. Deforestación en México: un análisis preliminar. Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas A. C. México, D. F., México. 40 p. [ Links ]

López de U., G. I. y. P. Fernández S. 1998. Curvas ROC. Cuadernos de Atención Primaria 5 (4): 229-235. [ Links ]

Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura (FAO). 2011. Situación de los bosques del mundo. Roma, Italia. 716 p. [ Links ]

Plamen, G., M. and I. L. Stoyanov. 2005. Ecological profiles of harvestmen (Arachnida, Opiliones) from Vitosha Mountain (Bulgaria): a mixed modelling approach using gams. Journal of Arachnology 33 (2): 256-268. [ Links ]

Reséndez V., K. L., M. P. González C., I. Chairez H. y O. Díaz M. 2013. Aspectos biológicos, ecológicos y usos del mezquite. Vid supra, Visión Científica 5 (1): 35-38 [ Links ]

Ríos S., J. C., R. Tracios C., L. M. Valenzuela N., G. Sosa P. y R. Rosales S. 2011. Importancia de las poblaciones de mezquite en el norte-centro de México. CENID-RASPA. Durango, Dgo., México 220 p. [ Links ]

Rodríguez S., E. N., G. E. Rojo M., B. Ramírez V., R. Martínez R., M. de la C. Conga H., S. M. Medina T., H. H. Piña R. 2014. Análisis técnico del árbol del mezquite (Prosopis laevigata Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd.) en México. Ra Ximhai 10 (3): 173-193. [ Links ]

Rzedowski, J. 1988. Análisis de la distribución geográfica del complejo Prosopis (Leguminosae, Mimosoideae) en Norteamérica. Acta Botánica Mexicana 3: 7-19. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Semarnat). 2004. Anexos de la Evaluación del Programa Nacional de Reforestación Pronare 2003. Semarnat. México, D. F., México. 42 p. [ Links ]

Soberón, J. and M. Nakamura. 2009. Niches and distributional areas: concepts, methods, and assumptions. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Washington, DC, USA. Num. 106. pp. 19644-19650. [ Links ]

Universidad Autónoma Chapingo (UACh). 2010. Informe de evaluación externa de los apoyos de reforestación ejercicio fiscal 2009. Conafor. México, D. F., México. 140 p. [ Links ]

Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León (UANL). 2009a. Reforestación: evaluación externa ejercicio fiscal 2008, Informe de Entidades Federativas, Resultados, Aciertos y Áreas de Oportunidad. Conafor. México, D. F., México. 388 p. [ Links ]

Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León (UANL). 2009b. Reforestación: evaluación externa ejercicio fiscal 2008, Informe de Entidades Federativas, Resultados, Aciertos y Áreas de Oportunidad. 2008. Conafor. México, D. F., México. 197 p. [ Links ]

d Contribution by author. Abraham Palacios Romero: research conception and approach, experimental development and results analysis; María de la Luz Hernández Flores: research conception and approach, experimental development and mapping; Rodrigo Rodríguez Laguna: results analysis and revision of the manuscript; Edith Jiménez Muñoz: drafting of the manuscript; David Tirado Torres: revision of the manuscript.

Received: October 05, 2015; Accepted: January 01, 2016

text in

text in