Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

Print version ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.8 n.3 Texcoco Apr./May. 2017

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v8i3.36

Articles

Flowering and fruiting of litchi under different agroecological conditions in Veracruz, Mexico

1Instituto Tecnológico Superior de Zongolica. Carretera a la Compañía S/N, Tepetlitlanapa, km 4. Zongolica, Veracruz. CP. 95005. (elaguas2@hotmail.com).

2Colegio de Postgraduados-Campus Veracruz. Carretera Federal Xalapa-Veracruz, km 88.5. Predio Tepetates, Mpio. de Manlio F. Altamirano, Veracruz. CP. 91674. (geliseo@colpos.mx; octavior@colpos.mx).

The litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) in Mexico, has had a significant increase in plantations in the last two decades, settled in warm regions in several cases, where there is a very marked alternation of production. The objective was to evaluate the flowering and fruiting of litchi, in orchards with different agroecological conditions and management, in the central and northern regions of the state of Veracruz in the 2010 year. Six contrasting orchards were selected, five with cv. Mauritius and one with 'Brewster', and in each one maximum and minimum temperature thermometers were placed. In order to follow the sprout length, inflorescences, berthing of fruits and harvested fruits, four sprout were marked per cardinal point, in 10 trees per orchard. The floral and vegetative sprouts were counted per m2 of tree top, in the middle part of the tree. A physical-chemical analysis of the soil was carried out in each orchard. In order to know the management, a questionnaire was applied to the producers. The altitude of the orchards was between 7 and 732 m, minimum temperatures ranged from 13.5 to 18.1 °C, which influenced the flowering response, where the Tuxpan 71.63% and Yecuatla orchards stood out with 66.28%. The fruiting and yield presented variation according to the cultivar, temperatures and management practices; for ‘Mauritius’, the outstanding orchards were Tuxpan with 7.4 t ha-1 and Yecuatla with 3.6 t ha-1. For ‘Brewster’ the yield was 4.1 t ha-1, in the Tolome orchard.

Keywords: Litchi chinensis; flowering; minimum temperature; orchard management; production

El litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) en México, ha tenido un incremento significativo en plantaciones en las últimas dos décadas, en varios casos se estableció en regiones cálidas, donde presenta marcada alternancia de producción. El objetivo fue evaluar la floración y fructificación de litchi, en huertas con diferentes condiciones agroecológicas y manejo, en las regiones centro y norte del estado de Veracruz en el año 2010. Se seleccionaron seis huertas contrastantes, cinco con el cv Mauritius y una con ‘Brewster’, y en cada una se colocaron termómetros de máximas y mínimas para el registro de temperaturas. Para dar seguimiento a la longitud de brotes, inflorescencias, amarre de frutos y frutos cosechados, se marcaron cuatro brotes por punto cardinal, en 10 árboles por huerta. Se contabilizaron los brotes florales y vegetativos por m2 de copa, en la parte media del árbol. Se realizó un análisis físico-químico del suelo, en cada huerta. Para conocer el manejo, se aplicó un cuestionario a los productores. La altitud de las huertas estuvo entre 7 y 732 m, las temperaturas mínimas variaron de 13.5 a 18.1 ºC, lo que influyó en el respuesta en floración, donde destacaron las huertas de Tuxpan 71.63% y Yecuatla con 66.28%. La fructificación y rendimiento presentó variación acorde al cultivar, temperaturas y prácticas de manejo; para ‘Mauritius’, las huertas sobresalientes fueron Tuxpan con 7.4 t ha-1 y Yecuatla con 3.6 t ha-1. Para ‘Brewster’ el rendimiento fue de 4.1 t ha-1, en la huerta Tolome.

Palabras claves: Litchi chinensis; floración; manejo de huertas; producción; temperatura mínima

Introduction

The litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) is a fruit tree of the Sapindaceae family, a subtropical evergreen tree that is cultivated throughout Southeast Asia, particularly in China (Zhou et al., 2008; Sung et al., 2012). It is characterized by the production of intense red fruits of pleasant taste (Galán, 1987). This species is popular in Asia, but is less well known in Africa, Europe and Latin America (Menzel and Wait, 2005). Litchi cultivation was introduced in Mexico at the beginning of the 20th century, in the state of Sinaloa; but it was not until the decades of the 70 and 80’s that the first commercial plantations were established. At national level in the last 15 years there has been a significant increase in litchi litter, from 748 ha in 2000 to 3 738 ha in 2013 (SIAP, 2015). The states that excel in the production of the licthi crop are Veracruz, Oaxaca, San Luis Potosí, Hidalgo and Puebla (De la Garza, 2003).

This is due to the interest of some Mexican producers on the demand for this fruit in the United States, Canada and the European Union. As well as the growing national market (Osuna et al., 2008). The problem presented by this crop is the alternation of production; there are cultivars with different levels of alternation and others with strong interaction with the elements of the climate that accentuate the problem; on the other hand, there is evidence that management practices such as ring-banding and root pruning favor flowering in litchi trees (Smit et al., 2005; García-Pérez and Martins, 2006). The state of Veracruz has an area of 1 659 hectares and a production of 8 491.99 tons, with a yield in the last six years of 3.15 to 5.64 t ha-1 (SIAP, 2015). There are plantations in 24 municipalities, mainly in Tihuatlán, Coatzintla, Tlapacoyan, Papantla, Córdoba and Paso de Ovejas; where the two predominant cultivars are Mauritius and Brewster.

The litchi plantations in Veracruz are in areas with hot humid and subhumid climates, where high temperatures occur frequently in autumn and winter, which in several years has limited flowering, accentuating the problem of alternation of production. Due to the orographic heterogeneity of the state of Veracruz, there is a wide range of climates; in some of these, litchi cultivation has been established; some sites are adequate and favor flowering and crop yield.

There are no studies of agroecological zoning for litchi cultivation in Mexico, so that farmers establish their plantations without having sufficient information of crop requirements, such as dry winters, with cool temperatures, free of frost and relative humidity around 75% (Zhou et al., 2008). Therefore, the objective was to evaluate the flowering and fruiting of litchi ‘Mauritius and Brewster’, in orchards with different agroecological conditions and management in the central and northern regions of the state of Veracruz, Mexico.

Materials and methods

Description of the studied area

The research was carried out in five municipalities in the central and northern regions of the state of Veracruz. The municipalities are located between the coordinates 20° 54’58.4” north latitude, 97° 25’ 29.2” west longitude and 18° 50’ 47.7” north latitude, 96° 23’ 08.9” west longitude, and are in the climates group of: Aw (tropical with summer rains, Aw0 and Aw2 subtypes), Af (tropical with year-round rainfall) and Am (tropical monsoon) (Soto, 1986). The study gardens are located at different altitude between the range of 7 to 732 m.

Sample size

For the orchards selection, a tour was made in the central and northern regions of the state of Veracruz and six litchi orchards with contrasting agroecological conditions were selected. Specific characteristics such as age of trees, between 8 and 12 years, types of cultivars (Mauritius and Brewster) and geographic location were considered. A systematic randomized probabilistic method (MASIS), in the form of a zigzag, was used to select 10 trees in the orchards, adding a total of 53 trees (43 were from ‘Mauritius’ and 10 from ‘Brewster’) where variables of flowering and yield were recorded.

Temperature measurement

For temperature recording (ºC), four TFA® thermometers of maximum and minimum were placed in each cardinal orientation, in the outer middle part of the tree top by orchard, during three months (November to January). Considering 1.5 months prior to flowering to the end of it. The maximum and minimum temperature data were recorded at nine o’clock each day.

Characteristics of sprouts

One month before the beginning of flowering, four sprouts were randomly marked in each cardinal orientation, adding a total of 16 sprouts per tree. These were measured in length (cm), basal diameter (mm) and number of leaves. Follow-up was made to see if the new sprouts were vegetative or floral.

Flowering

The number of floral and vegetative sprouts per square meter was recorded in 10 trees per orchard during the flowering stage. For this, a wooden frame of 1 m2 of area was used, which was placed in the middle part of the tree cup in each cardinal orientation. The information obtained was registeder in Microsoft Excel® v.7 program and the percentage of floral and vegetative sprouts per tree was calculated.

Fructification

In order to measure tree fruit yield and estimate the yield of litchi t ha-1, 16 sprouts per tree were monitored. The fruits per cluster were counted 30 days after the banding and 15 days before harvest.

Soil analysis

Soil sampling by orchard was done in a zig-zag with five sampling points at two depths: one sample (M1) of 0-20 cm and sample two (M2) of 20-40 cm, which were analyzed in the Laboratory of Plant Nutrition of the College of Postgraduates, Campillo Montecillo, and physical and chemical characteristics of the soil were determined.

Cultivation management

In order to know the management of the orchards; an interview was conducted with each producer, with the support of a questionnaire with open and closed questions. Considering different aspects: cultivars, management practices, crop phenology, factors and elements of the climate, harvest indicators, postharvest management, yield, marketing and technical advice.

Data analysis

The data were integrated in an Excel spreadsheet Version 2010® and then in the Statistica®v.7 program, descriptive graphs were made corresponding to floral and vegetative sprouts, as well as temperature and number of fruits per cluster. An analysis of variance was performed with the proc Anova procedure and test of means (Tukey, α≤ 0.05), with the SAS v. 9.3 for Windows (Statistical System Inc., 2004).

Results and discussion

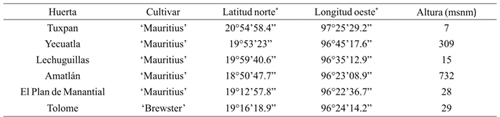

Table 1 shows the latitude, longitude, and altitude of the evaluated orchards. The extreme latitude and altitude varied from 18° 50’ 47.7” north latitude and 732 m (Amatlán orchard) to 20° 54’ 58.4” west longitude and 7 m (Tuxpan orchard), these differences are reflected in the flowering season, December For Amatlán and January for Tuxpan and intensity of flowering, both orchards with the cultivar Mauritius. The other orchards, with average values presented different responses, which evidences the influence of the geographic location and altitude, on the temperatures and the flowering response. Plantations closer to the subtropical fringe, where temperatures are more extreme (e) or intermediate altitude (in this case 309 m), will have a better flowering response (Mitra and Pathak, 2010).

Table 1 Geographic location and altitude in six litchi orchards in the state of Veracruz.

*= Datos obtenidos GPS Garmin map76csx®.

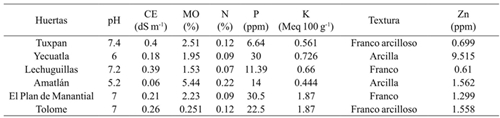

Soil analysis

Table 2 shows the results of soil analysis, pH was found close to neutral in five of the six orchards, this is within the requirement for litchi, according to Galán (2003). The Amatlán orchard presented the lowest pH (5.2), an acidic soil characterized by availability problems of some nutrients (Marschner, 2002). This orchard with the cultivar Mauritius was the one with the lowest flowering percentage (39.44%) and the lowest number of fruits per cluster 2.1.

Table 2 Principal physical and chemical characteristics of the soil, in six litchi orchards in the state of Veracruz.

The MO content ranged from 0.225% (Tolome) to 5.44% (Amatlán), this is related to the differences in soil management and undoubtedly has an effect on tree response. Nitrogen (N) was between 0.07% (Lechuguillas) and 0.22% (Amatlán), this difference is expressed in the length of vegetative sprouts and in the percentage of vegetative sprouts, which was 60.56 ± 25.4% for the Amatlán orchard, it is pointed out that an excess in nitrogen concentration causes an increase of vegetative sprouts and decrease of flowering Li et al. (2001). Potassium (K) an important nutrient for fruit development, presented a wide range, the Amatlán orchard with 0.14 Meq 100 g-1 had the lowest value, which can be associated to the initial and final lower berthing of fruits per cluster. This is consistent with the literature saying that the lack of potassium (K) and water limit fruit development, which is reflected in the final yield (Menzel et al., 1992; Mitra and Pathak, 2010).

The electrical conductivity ranged from 0.06 to 0.4 dS m-1. This means that they are soils low in salts, and that according to Vázquez (1996), soils with electrical conductivity less than 2 dSm-1 are considered non-saline and suitable for the cultivation of fruit trees. In relation to texture, loamy and sandy soils were determined. The above agrees with what is reported in the literature, that the most suitable soils for the litchi are silts, acids or silts of vega river (Baker, 2002).

Management practices in the crop

There are important differences in the management of the orchards (Table 3), among which the cultivar Mauritius, Lechuguillas stands out with complete organic management, after Tuxpan and Plan de Manantial with an intermediate management and finally Yecuatla and Amatlán only with weed control; this condition, coupled with the geographical location and soil characteristics, was reflected in the flowering and fruit yield per unit area, where the Tuxpan orchard (71.63% and 7.4 t ha-1) stood out, followed by the Yecuatla orchard (66.28% and 3.6 t ha-1).

Table 3 Main management practices, flowering and yield of litchi orchards, in the state of Veracruz in the 2010 year.

In contrast, the Tolome orchard with the Brewster cultivar, located in an agroecological condition that was not favorable to the crop, but with complete conventional management, presented a very acceptable response in flowering and yield (73.8% and 4.1 t ha-1), this coincides with what is reporte don the literature, which indicates that an adequate application of nutrients and other management practices in trees, favor the flower buds (Mitra and Pathak, 2010).

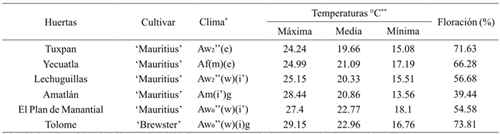

Temperatures and flowering

The temperatures recorded from November 2009 to January 2010, which were the months of the flowering process in the orchards evaluated, are presented in Table 2. The minimum temperatures ranged from 13.5 to 18.1 °C and the maximum temperatures from 24.2 to 29.1 °C. For ‘Mauritius’the orchard that had the greatest flowering was Tuxpan with 71.63%. In contrast, the orchard with lower flowering was Amatlán with 39.44%, this last recorded a minimum temperature of 13.5 °C, and is located at 732 msnm. Of the six orchards, Tolome registered the highest maximum temperature with 29.15 °C, it is located at 29 msnm, in this orchard predominates Brewster cultivar and presented 73.8% of flowering, it should be noted that in this one ringing of main branches is performed, as a practice to promote flowering. The best responses in flowering are similar to those reported for litchi, cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions of the world Zhou et al. (2008); the geographical location of these are between 19° and 24° north latitude (Mitra and Pathak 2010). Therefore, the greater flowering presented by the orchard of Tuxpan, can be associated to its location at 20º 53’ west longitude.

Table 4 Temperatures and flowering percentage in six litchi orchards in the 2009 and 2010 cycle in the state of Veracruz.

*= Localidades y climas del estado de Veracruz (Soto, 1986). **= temperaturas obtenidas de termómetros de máximas y mínimas TFA®.

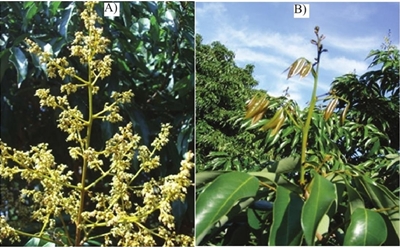

When comparing the response of the El Plan de Manantial orchard with the Mauritius cultivar and the Tolome orchard with ‘Brewster’, that are only 7 km of distance away so they have very similar characteristics in latitude and altitude, but the flowering was 54.58% for ‘Mauritius’ and 73.81% for ‘Brewster’. In addition to the cultivar factor, there are management differences between these orchards; in the Tolome orchard main branches ringing is performed to promote flowering, it has an annual fertilization program and has a micro sprinkler irrigation system, which due to the age of the trees is more efficien than the drip system used in El Plan de Manantial; which undoubtedly helps explaining the different flowering response (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Flowering litchi trees of the cultivars Mauritius (A) and Brewster (B) in the 2009-2010 cycle.

In Figure 2, a relationship between the flowering percentage and the minimum temperature means (°C) is presented. The highest percentage of flowering was in the Tolome orchard with the Brewster cultivar and among orchards of the cultivar Mauritius, Tuxpan presented the highest flowering, and had a minimum temperature of 15.08 °C, followed by the Yecuatla orchard, although the latter one has a minimum management, but with acceptable agroecological conditions for the crop. This is in agreement with the literature on the favorable effect of flowering when there are minimum temperatures around 15 °C (Menzel and Simpson, 1993; Chen and Huang, 2001).

Characteristics of vegetative sprouts, inflorescences and flowering percentage

In the orchards with the cultivar Mauritius, significant differences (p≤ 0.05) were found in all evaluated variables (Table 5). For the Brewster cultivar, only the mean and standard deviation of each variable are presented, with values lower than those of the cultivar Mauritius, except for the variable of floral sprouts that had the highest percentage with 73.8 ±11.9. According to the test of means (Tukey, α≤ 0.05); for the cultivar Mauritius, the Tuxpan orchard is superior in diameter (mm), length of bud (cm), number of leaves and flowering (%), as indicated above, this orchard favors its location at a higher North latitude, deep soil with clay loam texture and intermediate handling. In contrast, the Lechuguillas orchard, which had the lowest values in diameter, length and number of leaves per shoot, presented an intermediate flowering (56.67%), this orchard is under an organic management system, and is the only one that when harvesting the fruits, the bunch is cut with a portion of the vegetative sprout, for protection of the fruits and control of the trees height.

Table 5 Temperatures and flowering percentage in six litchi orchards in the 2009 and 2010 cycle in the state of Veracruz.

†= Medias con letras iguales en una misma columna no son estadísticamente diferentes, según la prueba de Tukey (α≤ 0.05). DMS= diferencia mínima significativa.

Figure 3 shows a floral sprout and a vegetative spruot of the Mauritius cultivar in the Lechuguillas orchard, where it can be seen that the new bud is relatively small, due to the influence of the sprout pruning during the fruit harvest.

Figure 3 Characteristics of a floral sprout (A) and a vegetative sprout (B) in the Lechuguillas orchard, Veracruz 2010.

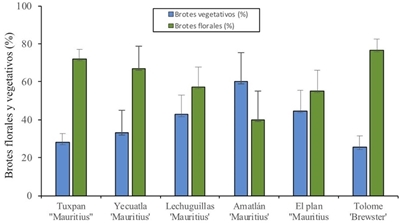

Figure 4 shows the percentage of floral and vegetative buds in each of the orchards for both cultivars, in general it is observed that a higher percentage of floral sprouts has a lower percentage of vegetative sprouts, which is in agreement with reported studies by O’Hare, (2004). For ‘Mauritius’, significant differences were found between orchards, the orchards of Tuxpan and Yecuatla stand out, which are characterized by the location of the northern latitude and the second by being at a medium altitude and minimum handling, this is indicative of the response in flowering, is closely related to the present agroecological conditions.

Figure 4 Percentage of floral and vegetative sprouts in six litchi orchards in the state of Veracruz, during the 2009-2010 cycle.

The orchards Lechuguillas and the Plan de Manantial that are in similar latitudes and altitudes presented a medium flowering, both have handling although in different level, reason why its answer is more associated to the handling. The Amatlán orchard, which is at a lower latitude and at a height outside the range recommended by Sotto (2002), and with a minimum handling, showed the lowest flowering, which shows that unfit conditions and poor management will affect the flowering response. In contrast, the Tolome orchard with ‘Brewster’, under non-favorable agroecological conditions, but with a complete conventional management, was the one that presented the highest percentage of floral sprouts (Figure 4).

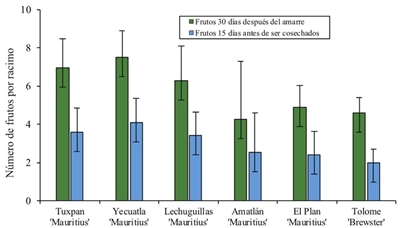

Number of fruits

In Figure 5, litchi fruit stockings per cluster are shown at 30 days post mooring and 15 days before harvest. There is a loss of litchi fruit that varies from 50 to 70%, between 30 and 70 days of fruit development. There is no statistical difference between orchards; the Tuxpan, Yecuatla and Lechuguillas orchards with ‘Mauritius’ presented more number of fruits per cluster in the two evaluation dates, and El Plan and Amatlán orchard had the lowest values. Tolome orchard with ‘Brewster’, presented the lowest number of fruits per cluster (1.9), although it had the highest percentage of floral shoots, but this is a characteristic of the cultivar, which is close to that reported by Crane et al. (1998) in litchi orchards with ‘Brewster’ in Florida, United States.

Figure 5 Mean value of litchi fruits per cluster, after mooring and pre-harvest in the cultivars Mauritius and Brewster.

The fruiting in ‘Mauritius’ is by bunch and has a reddish-pink color Figure 6A and ‘Brewster’ is characterized by lower fruit number per cluster, but the color is bright red Figure 6B (Sivakumar and Korsten, 2006).

Fruit yield per orchard ranged from 2.1 to 7.4 t ha-1. The Tuxpan orchard with 7.4 t ha-1 stands out, this orchard does not have irrigation, but it is located in a free soil in the margin of the river Tuxpan, and although it has an average handling, the conditions are favorable for the production; followed by the Yecuatla orchard with 3.6 t ha-1, with minimum management, but in agroecological conditions suitable for cultivation, the other three orchards presented lower yields, Lechuguillas 2.8 t ha-1, Amatlán 2.5 t ha-1 and El Plan 2.1 T ha-1. These results reinforce the importance of knowing the agroecological requirements of the crop since it is vital for its success. Otherwise, large investments in management practices have to be made in order to have acceptable yields, as reflected by the Tolome orchard with ‘Brewster’ yielding 4.1 t ha-1.

Conclusions

The contrasting conditions in latitude, altitude, temperatures, soil and management practices, between orchards, influenced the flowering and fruiting response of the litchi tres of Mauritius and Brewster cultivars. In flowering, the Tuxpan and Yecuatla orchards presented the highest percentages, the first one located at the highest northern latitude (LN) and the second in latitude and intermediate altitude (309 m), these conditions are favorable for the development of litchi trees. Fruiting showed significant variation among orchards, with the loss of 50 to 70% of the fruits harvested. However, the outstanding orchards were Tuxpan with 7.4 t ha-1 and Yecuatla with 5.6 t ha-1 with the cultivar Mauritius. The Tolome orchard with the Brewster cultivar had a yield of 4.1 t ha-1.

Literatura citada

Baker, S. A. 2002. Lychee production in Bangladesh. The lychee crop in Asia and the pacific. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, Bangkok, Thailand. 15-28 pp. [ Links ]

Chen, H. and Huang, H. 2001. China litchi industry: development, achievements and problems. Acta Horticulturae. 558: 31-39. [ Links ]

Crane, J. H.; Balerdi, C. F and Maguire, I. 1998. El litchi en Florida. Departamento de agricultura en la Universidad de Florida. http://hammock.ifas.ufl.edu. [ Links ]

De la Garza, A. 2003. El cultivo de litchi. Campo Experimental Huichihuayan. INIFAP. Huichihuayan, SLP. Folleto Técnico Núm. 1. 20 p. [ Links ]

Galán, S. V. 2003. Fruit: tropical and subtropical. In: Katz, S. H. and Weaver, W. W. (Eds). The encyclopedia of food and culture. Charles Scribners and Sons. New York, USA. 2:70-78. [ Links ]

Galán, S. V. y Menini, U. G. 1987. El litchi y su cultivo. Estudio FAO. Producción y Protección Vegetal 83. Roma Italia. 205 p. [ Links ]

García, P. E. e Martins, A. B. G. 2006. Florescimiento e frutificação de licheiras em função do anelamento de ramos. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 28(1):14-17. [ Links ]

Li, Y.; Davenport, T. L.; Rao, R. and Zheng, Q. 2001. Nitrogen, flowering and production of lychee in Florida. Acta Hortic. 558:221-224. [ Links ]

Marschner, H. 2002. Mineral nutrition of higher plants. 2da . (Ed.). Academic Press, London K. 389 p. [ Links ]

Menzel, C. M.; Carseldine, M. L.; Haydon, G. F. and Simpson, D. R. 1992. A review of existing and proposed new leaf nutrient standards for lychee. Scientia Hortic. 49:3-53. [ Links ]

Menzel C. M., and Simpson D. R. 1993. Fruits of tropical climate-fruits of sapindaceae. In: Encyclopedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. (Eds.). Macrae, R.; Robinson, R. K. and Sadler, M. J. Academic Press. Londres. 108 p. [ Links ]

Menzel, C. M. and Wait, G. K. 2005. Litchi and Longan botany, production and uses. CABI Publishing. British Library. London, UK. 297 p. [ Links ]

Mitra, S. K. and Pathak, P. K. 2010. Litchi production in the Asia-Pacific region. Acta Hortic. 863:29-36. [ Links ]

O’hare, T. J. 2004. Impact of root and shoot temperature on bud dormancy and floral induction in lychee (Litchi chinensis Sonn.). Sci. Hortic. 99(1):21-28. [ Links ]

Osuna, E. T.; Valenzuela, R. G.; Muy R. M. D.; Gardea, B. A. A. y Villareal, R. M. 2008. Expresión del sexo y anatomía floral del litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn). Rev. Fitotéc. Mex. 31(1):51-56. [ Links ]

Sivakumar, D. and Korsten, L. 2006. Influence of modified atmosphere packaging and postharvest treatments on quality retention of litchi cv. Mauritius. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 41(2):135-142. [ Links ]

Smit M.; Meintjes J. J.; Jacobs G.; Stassen, P. J. C. and Theron K. I. 2005. Shoot growth control of pear trees (Pyrus communis L.) with prohexadione calcium. Sci. Hortic. 106(4):515-529. [ Links ]

SIAP (Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera). 2015. Cierre de la producción agrícola por cultivo. http://www.siap.gob.mx. [ Links ]

Sotto, R. C. 2002. Lychee production in the Philippines. Lychee production in the Asia-Pacific Region. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, Bangkok, Thailand. 94-105 pp. [ Links ]

Soto, E. M. 1986. Localidades y climas del estado de Veracruz. Editorial Herb. Instituto nacional de investigaciones sobre recursos bióticos. Xalapa, Veracruz, México.137 p. [ Links ]

Vázquez, A. 1996. Guía para interpretar el análisis químico del agua y suelo. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo (UACH). Departamento de suelos. Segunda edición. México. 185 p. [ Links ]

Sung, Y. Y.; Yang, W. K. and Kin, H. K. 2012. Antiplatelet, anticoagulant and fibrinolytic effects of Litchi chinensis Sonn. Extract. Rep. Mol. Med. 5(3):721-724. [ Links ]

Zhou, B.; Chen, H.; Huang, X.; Li, N.; Hu, Z.; Gao, Z. and Lu, Y. 2008. Rudimentary leaf abortion with the development of panicle in litchi: changes in ultraestructure, antioxidant enzymes and phytohormones. Sci. Hortic. 117:288-292. [ Links ]

Received: January 2017; Accepted: March 2017

text in

text in