Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

Print version ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.7 n.1 Texcoco Jan./Feb. 2016

Articles

Genetic resources of cotton in Mexico: ex situ and in situ conservation and use

1Centro Nacional de Recursos Genéticos-INIFAP. Blvd. de la Biodiversidad Núm. 400. Tepatitlán, Jalisco. C. P. 47600. Tel: 3781065020.

2INIFAP-Campo Experimental Valle de México, Estado de México. (tovar.rosario@inifap.gob.mx).

3Colegio de Estudios Superiores Agropecuarios del estado de Guerreo. (q.obispoglez@hotmail.com).

4Sitio Experimental Tlaxcala- INIFAP. (investigador hasta diciembre de 2011).

5Campo Experimental Centro Altos, Jalisco-INIFAP. (ruiz.ariel@inifap.gob.mx).

Mexico is the center of origin of Gossypium hirsutum cotton; 11 of the 13 wild species of Gossypium in the occidental hemisphere are endemic to Mexico. In 2009- 2011, different activities were carried out focused on the elaboration of the diagnosis of genetic resources of cotton in Mexico. The results obtained in this study showed that on several expeditions done by Mexican and foreign scientists in 1978-2006, 980 accessions were collected in Mexico, G. hirsutum being the species with the greatest amount of gathered data, while the species with less gathered data were: G. armourianum, G. shwendimanii, G. laxum and G. arboreum. These accessions are stored at germplasm banks in the United States, China and Russia. The most widely recollected species is G. hirsutum, followed by G. aridum, the arborescent diploid wild species. The Gossypium genus is distributed throughout Mexico with a high endemism level; the areas with more natural diversity are located mainly in the southern and coastal areas of the country.

Keywords: Gossypium; collection; genetic diversity; wild species

México es el centro de origen del algodón Gossypium hirsutum, 11 de las 13 especies silvestres de Gossypium en el hemisferio occidental son endémicas de nuestro país. Durante el periodo 2009-2011, se realizaron diferentes actividades enfocadas principalmente a la elaboración del diagnóstico de los recursos genéticos del algodón en México. Los resultados obtenidos en este estudio mostraron que en México se han recolectado en las diferentes expediciones realizadas por científicos mexicanos y del extranjero tan solo del periodo de 1978 a 2006, 980 accesiones siendo la especie con mayor recolección G. hirsutum mientras que las especies con menor recolección fueron: G. armourianum, G. shwendimanii, G. laxum y G. arboreum. Estas accesiones se encuentran resguardadas en los bancos de germoplasma de los Estados Unidos de América, China y Rusia por mencionar algunos. La especie con mayor recolección es G. hirsutum seguido de G. aridum es la especie silvestre diploide arborescente. El género Gossypium se distribuye en el país con un alto nivel de endemismo, las áreas con mayor diversidad se ubican principalmente al sur del territorio nacional y en las zonas costeras del país.

Palabras clave: Gossypium; diversidad genética; especies silvestres; recolección

Introduction

Genetic resources are the basis for the food safety and sovereignty of a country, and raw material for the development of new varieties with characteristics that allow resistance to plagues, illnesses, water shortages, climatic changes, etc. According to Griffon (2008), the Creole races and other varieties are the result of the co-evolution process of the human culture and corresponding environments. These organisms are indicators of cultural diversity; their preservation is therefore as important as languages and ancient traditions. This author mentions that small farmers are the guardians and the main users of such agricultural diversity.

Increasing human activity has caused a progressive deterioration of genetic diversity. According to data from the World Conservation Monitoring Center, 12.5% of a total of 250 thousand plant species are at risk of extinction and at the same time, only 10% of the plant species have been assessed due to their agronomic or medicinal potential, as the case may be (Iriondo, 2001).

An important factor that has increased the risk of extinction of the Creole varieties is the unreasonable cultural expansion of genetically modified organisms. Four industrial cultures (soy beans [63%], corn [19%], cotton [13%] and canola [5%]) represented 100% of the area sown with commercial transgenic cultures in 2001, which represents the greatest cause of genetic erosion in the world present day (Griffon, 2008). It is important to consider the foregoing, especially in countries that are centers of origin to plant species such as Mexico.

The Mexican Republic, more specifically the area known as Mesoamerica, is a region with a wealth of flora, identified as a center of origin and diversity of cultivated plants that have acquired great importance worldwide (FAO, 1996), among which corn, chile, beans, cotton, tobacco, cacao, avocado, etc. are present (Lepíz and Rodríguez, 2006).

Cotton (Gossypium) has a cultural, financial and biological relevance in the world. Ulloa et al. (2006) report that Mexico is the center of origin of the Gossypium genus with 11 of the 13 diploid species (G. armourianum, G. lobatum, G. gossypioides, G. aridum, G. laxum, G. shwendimanii, G. thurberi, G. trilobum, G. davisonii, G. turneri and G. harknesii) and one tetraploid (Gossypium hirsutum), which together constitute a genetic pool useful in the utilization and improvement of this genus (Ulloa et al., 2006; Feng et al., 2011; Ulloa et al., 2013). Currently, the G. hirsutum species is the main cultivated cotton and contributes with almost 90% of the world production due to the characteristics of the fiber that it produces (Poelham and Sleper, 2003; Tovar et al., 2013); in addition, cotton seed is also an important food source as oil for human consumption and cottonseed meal for animals are extracted from its seed (Sunilkumar et al., 2006).

In order to preserve and promote a sustainable use of cotton, it is necessary to know about the current state of this resource in Mexico. It is important to have this information in order to achieve the rescue success of the genetic diversity of the Gossypium genus. Based on the foregoing, the planned objective was to research the state of the genetic resources of cotton in Mexico and their relation to the ex situ and in situ conservation and their uses.

Materials and methods

The research was done from January 2009 to December 2011 and in order to carry out the research, herbaria from different national institutions were visited, and a bibliographic review was done in reference to their ex situ and in situ conservation and the use of the genetic resources of cotton in Mexico.

Information sources. The collection records of cotton from 1978 to 2006 were considered: G. hirsutum, G. armourianum, G. aridum, G. gossypioides, G. laxum, G. lobatum, G. shwendimanii, G. turneri, G. thurberi, G. trilobum, G. lanceolatum, G. harknesii, and G. davidsonii, the cotton species reported in Mexico.

The information contained in the labels of the Gossypium genus was collected; this information is stored in the herbaria, germplasm or seed banks at the Universidad Autónoma Chapingo (UACH), the Colegio de Postgraduados (COLPOS), the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), the Instituto Nacional de Ecología (INECOL), the Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán (CICY) and the Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán (UADY). Furthermore, internet research was done in the World Biodiversity Information Network (REMIB), which provides information on herborized cotton samples. Each herbaria specimens was revised and photographed in order to capture the information contained in the collection card.

Mapping of the current distribution of Gossypium sp. A matrix of georeferenced data was integrated in Microsoft® Excel (2007), concerning the points of each accession in the Mexican Republic of each one of the species of Gossypium in the study. The following information was included in the matrix for each accession: genus, species, state, latitude, longitude and altitude. The geographical location of each one of the collection sites was verified through topographic maps with a 1: 50000 scale (INEGI, 2003), the Gazetteer of the Síntesis Geográfica Estatal (SIGE) of the Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI; 2000) for several states and the Interactive Atlas of Microsoft Encarta® (2010). The current distribution of the Gossypium species was mapped using the geographic coordinates of all the accessions considered in this study. The foregoing was done through the ArcGis system (ESRI, 2006). INIFAP’s Sistema de Información Ambiental Nacional (SIAN) was used to characterize the environmental conditions of the collection sites. SIAN is compiled in the Idrisi system (Eastman, 2006) and is comprised of climatic and topographic images in raster format, on a monthly, seasonal and annual scale with a resolution of 180 m. The climatic information contained in this system corresponded to the 1961-2003 period.

Taxonomic nomenclature. In order to reduce a mistake due to possible synonyms and ensure the correct name of the species, Fryxell was used as a reference (1992). It was assumed that the determinations of the herborized samples deposited in the consulted herbaria were correctly done; every time they were performed by experts in the area.

Information that was not considered. The samples from herbaria with insufficient information were not taken into consideration; for example, when the genus was shown without the species definition (Gossypium sp.) or when it was suggested to compare with another race of the G. hirsutum species (identified by the “cf” abbreviation.), and those where there was a certain affinity with a hirsutum race (identified by the abbreviation “aff”).

Results and discussion

Considering the information consulted for this research, the results indicate that among the 31 states and Mexico City, 27 states have reported the existence of native cotton species; the states where there has not been any report of native cotton species are: Aguascalientes, Coahuila, Hidalgo, Tlaxcala and Mexico City. It is important to note that it should be verified if there are other native cotton species in these states. The state where the largest number of cotton accessions (210) has been collected is Yucatán, with G. hirsutum (167) and G. barbadense (40) standing out. The states that continue in order of importance by number of collected accessions were the following: Baja California Sur (111), Michoacán (75), Campeche (70), Sonora (51) and Colima (47) (Figure 1). Finally and according to the information obtained in the herbaria, the presence of species with fiber that were introduced in the Old World, such as G. arboreum in Yucatán and G. herbaceum in the state of Baja California Sur, has been reported.

In the study of the inventory on cotton, it was found that in the different consulted sources that 908 accessions have been collected in Mexico. The number of Gossypium samples collected by species in the Mexican Republic from 1978- 2006 is presented in Table 1. As it has been observed, the G. hirsutum species presents the highest number of collected accessions with 451, followed by the diploid wild species G. aridum with 111 and G. barbadense with 76 samples. It is important to mention that in the 90 reported accessions, the collected species is not specified (Table 1).

Table 1 Number of Gossypium accessions collected by species in the Mexican Republic. 1978-2006 period.

| Especie | Núm. accesiones | Especie | Núm. accesiones |

|---|---|---|---|

| arboreum | 1 | klotzschianum | 20 |

| aridum | 110 | lanceolatum | 20 |

| armourianum | 9 | laxum | 5 |

| barbadense | 76 | lobatum | 30 |

| davidsonii | 48 | shwendimanii | 7 |

| gossypioides | 15 | thurberi | 27 |

| harknesii | 43 | trilobum | 5 |

| herbaceum | 1 | turneri | 22 |

| hirsutum | 451 | sp. | 90 |

This amount of samples reported in the herbaria has been the product of the different expeditions done by Mexican, American, Chinese and Russian scientists, which are stored in the corresponding germplasm banks in these countries (Pérez et al., 2011).

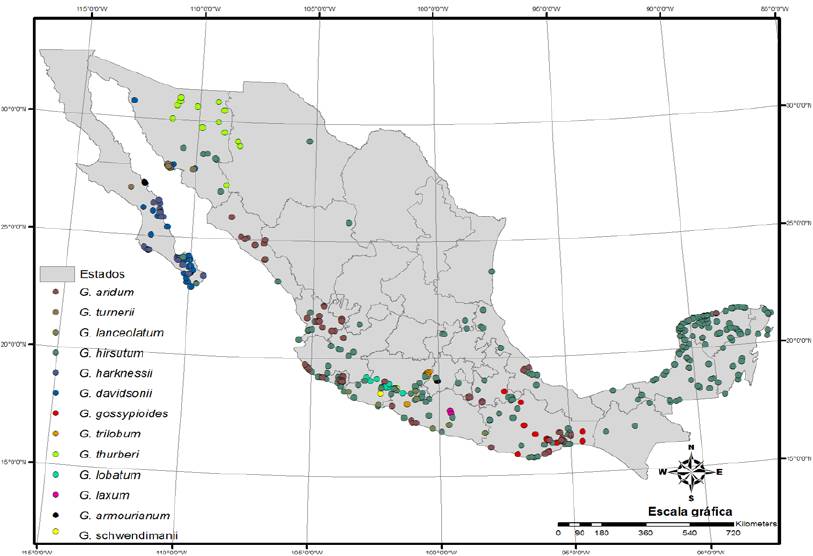

Distribution areas of the species. Figure 2 presents the geographic distribution of Gossypium, where it can be observed that its distribution is extensive, from the northeast of the country in the states of Sonora, Baja California Sur and Sinaloa, to the southeast and the Yucatán Peninsula. This indicates that the Gossypium genus can easily adapt to the weather and that it can develop under a diversity of environmnetal conditions, which coincides with what was indicated by Morrone (2005). It was reported that according to the classification of the biogeographic states of Mexico, the Gossypium genus is located in the biogeographic provinces of Baja California, Sonora, Mexican Pacific Coast, Gulf of Mexico, Yucatán Península, Chiapas and Balsis River, areas with weather conditions that go from arid to humid and semi-warm to warm (Medina et al., 1998), associated to one geological, edaphic diversity and of many vegetation and habitat types.

Figure 2 also shows that the G. aridum species is distributed from Sinaloa to Guerrero; G. trilobum in Michoacán and Guerrero; G. turneri and G. thurberi in Sonora and Chihuahua; and G. davidsonii and G. shwendimanii which have only been detected in the state of Michoacán; while G. laxum and G. gossypioides are endemic to Guerrero and Oaxaca, respectively. The G. armourianum species is located in Baja California Sur and in the State of Mexico, and G. lanceolatum is distributed in the states of Colima, Michoacán and Guerrero.

Geographically it can be observed that the most genetic diversity of this genus is concentrated in the southern part of the country. This coincides with what is reported by Prado et al. (1978) and Pérez and Ruiz (2010) who mention that the center of origin and the highest concentration of genetic diversity of the cultivated G. hirsutum species are located within the geographical limits of Mexico and that the native race known as “yucatanense” is located in the natural vegetation of the northern coastal area of the Yucatán Peninsula.

Endangered local species or races. According to reports by Ulloa et al. (2006) and Pérez and Hernández (1992), the wild Gossypium species that could be at risk of extinction are: G. thurberi, G. turneri, G. harknessi, G. davidsonii and G. lobatum which are located in the San Carlos Bay in Guayamas, Sonora, Los Cabos, Baja California Sur and in the state of Michoacán. The attributable reasons to this threat are, among others: vegetation removal for new touristic developments; unplanned urban growth; the replacement of natural areas by agricultural production zones; and, deforestation in favor of the establishment of other exploitations systems such as the cultivation of grassland.

In situ conservation. In situ conservation of semi-domesticated cotton (G. hirsutum) is done by ethnic groups. Several Huicholes indigenous groups are located in northeast Nayarit, in the mountains of the Sierra Madre, and they provide in situ conservation of some wild cotton plants of G. hirsutum which are used in religious ceremonies (Ulloa et al., 2006). Hernández et al. (1984) quoted by Pérez et al. (2011) reported that in the southern part of the coffee-growing region of Oaxaca, at an approximate altitude of 1 000 meters above sea level, inhabitants of that zone preserve G. barbadense, brasiliense race by in situ means. There are very few reports about the zones where the in situ conservation is done. It is therefore necessary to carry out activities of collection and preservation, not only of the hirsutum species, but of the Gossypium species in general, as well as an exhaustive ethnobotanical review, defining potential uses and generating new alternatives for their preservation.

Ex situ conservation. According to the information collected in different research institutions, it was found that the vegetable germplasm bank of the Universidad Autónoma Chapingo stores the seeds of six accessions of semi-domesticated cotton of the hirsutum species under adequate temperature and humidity conditions. It is important to point out that the information about the passport data of such accessions is limited.

Existing collections in botanical gardens. There are four botanical gardens that preserve a total of 126 accessions of the Gossypium genus; the majority of them are located in the southeastern region of Mexico. It is worth noting that the botanical garden of the Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas and Pecuarias (INIFAP), located in Iguala, Guerrero, is one with a formal collection of accessions of cotton germplasm native to Mexico, in addition to infrastructure and qualified personnel for the handling and preservation of the plants. The preservation of the cotton germplasm native to Mexico through the botanical garden thus guarantees the preservation and research of this natural resource which is a domesticated genetic patrimony, used and preserved since the pre-Hispanic era (Arias et al., 2010).

It is important to emphasize that the germplasm collected by scientists during the expeditions, along with the material obtained through donations and exchanges with other banks, constitute the germplasm collections (Wallace et al., 2009). In this contest, Campbell et al. (2010) carried out an exhaustive research with the purpose of knowing the global status of the genetic resources of the Gossypium genus. These authors reported a total of 60 118 accessions collected in the world, which are concentrated in eight countries: the United States, India, Brazil, Australia, China, France, Russia and Uzbekistan. It is important to mention that these authors indicate in their report that the germplasm banks of Russia and China, among their accessions, also have cotton germplasm with Mexican origins.

Presently, the United States has the largest collection of cotton germplasm in the world, which is stored in the Department of Agriculture (USDA) and is comprised of more than 10 000 accessions that come from all species of Gossypium (Campbell et al., 2010). The seed of these accessions has been accumulated for years and is a significant genetic capital from several countries, among which is Mexico. The individual samples of the seed represented in the bank were obtained by the collectors during exploratory expeditions to several parts of the world (Percival et al., 1999). The germplasm banks of global importance that have done exchanges with the USDA include the Botanical Garden of Cotton of the INIFAP; Institut de Recherche du Coton et des Textiles Exotique in France; Central Institute for Cotton Research in India; N. I. Vavilov Institute of Research in Russia; Germplasm Resources Research Division, People’s Republic of China; Centre de Coopération Internationale en Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement (CIRAD) in France; Empresa Brasileira de Investigación Agropecuaria (EMBRAPA) in Brazil, among others (Percival et al., 1999).

CIRAD is another research center that preserves one of the largest collections of genetic cotton resources. The center preserves more than 3 000 accessions of cotton that come from more than a hundred countries. CIRAD’s collection is a valuable tool for the stocking of genetic research programs, using the classic selection techniques, of specific hydration or of assisted selection with molecular markers (Dessauw and Hau, 2006a; Dessauw and Hau, 2006b).

Use of germplasm in genetic improvements. In Mexico, the development of improved varieties of conventional cotton (G. hirsutum) requires between 12 and 15 years of research using the wide genetic variability presented by the semi-wild cotton of this species (Hernández-Jasso, 2009; personal communication). It is worth mentioning that the collections of several semi-domesticated and wild cotton of the G. hirsutum species has been the basis for the formation of some varieties such as: Acala, Deltapine, Coker, among others (Ulloa et al., 2006; Tovar et al., 2013).

Research carried out between 1942 and 1985 by the Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Agrícolas (INIA), today INIFAP, about the genetic improvement of cotton was significant and contributed greatly to cotton producers in Mexico. During this period, the INIA released eight varieties (Table 2), among which stands out the first released and registered variety before the Servicio Nacional de Inspección y Certificación de Semillas (SNICS), with the name “CAERI-76”.

Table 2 Varieties of cotton obtained by the Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Agrícolas (INIA) from 1963 to 1985.

| Nombre de la variedad | Año obtenida | Condición humedad | Lugar de adaptación |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instituto-A | 1963 | Riego | Comarca Lagunera |

| Instituto-B | 1963 | Riego | Comarca Lagunera |

| México-910 | 1973 | Riego | Sonora |

| CAERI-76 | 1977 | Temporal | Región Soconusco, Chiapas |

| CIAPAC-77 (Apatzingán-812) | 1978 | Riego | Apatzingán, Michoacán |

| Apatzingán-81 | 1981 | Riego | Apatzingán, Michoacán |

| México RH-81 | 1981 | Riego | Tamaulipas, Michoacán, Baja California Norte y Sur |

| Nazas RCH | 1981 | Riego | Comarca Lagunera |

The name CAERI-76 means "Campo Agrícola Experimental Rosario Izapa" (Prado, 1983). This variety was obtained from the Acala 1517-C variety through the masal selection method and the repetition of progeny furrows. Their characteristics were: high fiber quality and slightly superior yield in comparison to the Detapine 16 variety. Due to the high fiber quality, there was a wide acceptance by the producers of the Soconusco region, sowing around 15 to 20 thousand hectares (Robles, 1982).

From 1985 to 2009, the INIFAP released 12 varieties with high yield and fiber quality for the cotton zones in the north of the country, the names of which are: Nazas 87, CIANO Cubachi-86, Laguna 89, CIAN 95, CIAN Precoz 2, CIAN Precoz 3, CIANO Álamos, CIANO Yaquimi-86, CIANO Tajimaroa, CIANO Cocorim-92 and Juárez 91 (Espinosa et al., 2004; SNICS, 2009; Arias et al., 2010). It is important to mention that the COCORIM-92 and CIANO YAQUIMI-86 varieties were not adopted by the producers of the state of Sonora due to the fact that they preferred to use the conventional varieties from the United States and those recommended by the seed companies, as well as the introduction of the first transgenic varieties in the experimental phase at the beginning of the 1990’s (Arturo Hernández-Jasso. Com. Pers, 2009).

Conclusions

27 states of the Mexican Republic have reported the existence of native cotton species.

The states with the highest number of Gossypium species collected are: Michoacán, Baja California Sur, Guerrero, Oaxaca, Sonora, Sinaloa, Veracruz and Yucatán.

G. hirsutum is the species that has been collected the most followed by G. aridum, the wild diploid arborescent species.

The Gossypium genus is distributed in the country with a high endemic level; the areas with the most diversity are mainly located in the southern and coastal areas of the country.

Literatura citada

Arias, M. A.; Mallén, C. R.; Garza, D. R.; Rentería, J. B A.; Reyes, L. M.; Zamora, P. M.; Tovar, M. R. G.; Vargas, S. M. y Gómez, T. H. 2010. 25 años contribuyendo al desarrollo rural sustentable. Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP). México, D. F. 136 p. [ Links ]

Campbell, B. T.; Saha, S.; Percy, R.; Frelichowski, J.; Jenkins, J. N.; Park, W.; Mayee, C. D.; Gotmare, V.; Dessauw, D.; Gband, M.; Du, X.; Jia, Y.; Constable, G.; Dillon, S.; Abdurakhmonov, I. Y.; Abdukarimov, A.; Rizaeva, S. M.;Abdullaev, A.A.; Barrose, P.A. V.; Padua, J. G.; Hoffman, L. V. and Podolnaya, L. 2010. Status of global cotton germplasm resources. Crop Sci. 50(4):1161-1179. [ Links ]

Dessauw, D. and Hau, B. 2006 a. Les resources génétiques du cotonnier au Cirad. Centre de coopération internationale en recherche agronomique pour le développement: http://www.cirad.fr. [ Links ]

Dessauw, D. and Hau, B. 2006 b. Inventory and history of the CIRAD cotton (Gossypium spp.) germplasm collection. Plant Genet. Resour. Newsl. 148:1-7. [ Links ]

Eastman, J. R. 2006. IDRISIAndes: guide to GIS and image processing. Clark Labs, Clark University. Worcester, Massachussets, USA. 327 p. [ Links ]

Espinosa, C. A.; Piña J. R.; Oliveira A. C. y Mora M. V. 2004. Listado de variedades liberadas por el INIFAP de 1980 a 2003. Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca yAlimentación (SAGARPA), Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP), Centro de Investigación Regional del Centro, Campo Experimental Valle de México. Chapingo, Estado de México. 28 p. [ Links ]

FAO. 2010. Agroecología. Sobre la extinción de variedades y razas criollas. ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep7fao/010/i0112s/i0112s11. [ Links ]

Fryxell, P. A. 1992. Juss. In: flora de Veracruz. Fascículo 68. Instituto de Ecología. 50 p. [ Links ]

Feng, Ch.; Ulloa, M.; Pérez, M. C. and Stewart, J. M. 2011. Distribution and molecular diversity of arborescent Gossypium Species. Botany. 89(9):615-624. [ Links ]

INEGI. 2003. Carta topográfica escala 1:50000 serie 3. Edición individual 2003, primera impresión. Dirección General de Geografía. Aguascalientes, Aguascalientes, México. [ Links ]

INEGI. 2000. Síntesis de información geográfica de los estados. Publicación única. Edición 1999. Aguascalientes, Aguascalientes, México. 100 p. [ Links ]

INIFAP. 1987. Listado de variedades liberadas por el INIA de 1942 a 1985. Secretaría de Agricultura y Recursos Hidráulicos (SARH). Publicación Esp. Núm. 22. 70 p. [ Links ]

Iriondo, A. 2001. Conservación de germoplasma de especies raras y amenazadas (revisión). Invest. Agr. Prod. Prot. Veg. 16(1):1-23. [ Links ]

Lépiz, I. R. y Rodríguez, E. G. 2006. Los recursos fitogenéticos de México. In: Informe Nacional 2006. Recursos Fitogenéticos en México para la Alimentación y la Agricultura. Secretaría de Agricultura Ganadería, Pesca y Alimentación (SAGARPA)- Sociedad Mexicana de Fitogenética, Servicio Nacional de Inspección y Certificación de Semillas (SNICS). 2-17 pp. [ Links ]

Medina, G. G.; Ruiz, C. J. A. y Martínez, P. R. A. 1998. Los climas de México: una estratificación ambiental basada en el componente climático. Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP)- Centro de Investigación Regional Pacífico Centro. Conexión Gráfica. Guadalajara, Jalisco, México. Libro Técnico Núm. 1. 103 p. [ Links ]

Microsoft. 2010. Encarta. Interactive World Atlas. Software y base de datos interactiva. London, England. 274 p. [ Links ]

Microsoft. 2007. Hoja de cálculo Excel para Office Vista. Manual del usuario. London, England. 274 p. [ Links ]

Morrone, J. J. 2005. Hacia una síntesis biogeográfica de México. Rev. Mex. Biod. 76:207-252. [ Links ]

Percival, A.E.; Wendel, J.E. and Stewart, J.M. 1999. Cotton: origin, history, technology, and production. John Wiley & Sons. 33-63 pp. [ Links ]

Pérez, S. L. y Hernández, A. J. 1992. Colecta de especies silvestres de Gossypium por los estados de Sonora, Baja California Sur y Sinaloa. Resumen. In: XIV Congreso Nacional Fitogenética. 474 p. [ Links ]

Pérez, M. C.; Tovar, M. R. G.; Obispo, Q. G.; Ruíz, J. A. C.; Tavitas, L. F. y Jolalpa, J. L. B. 2011. Los recursos genéticos del algodón en México. Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP). Libro Técnico Núm. 5. 120 p. [ Links ]

Pérez, M. C. y Ruiz, J. A. C. 2010. Diagnóstico de la situación actual de los recursos genéticos del algodón en México. Resumen. In: V Reunión Nacional de Investigación Agrícola. 204 p. [ Links ]

Poelham, J. M. y Sleper, D. A. 2003. Mejoramiento genético de las cosechas. Edit. Limusa. 385 p. [ Links ]

Prado, M. R. 1983. Logros y aportaciones de la investigación agrícola en el cultivo del algodón. Secretaría de Agricultura y Recursos Hidráulicos (SARH). Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Agrícolas (INIA). 42 p. [ Links ]

Prado, M. R.; Quintín, G. O. y Godoy, S. A. 1978. Algodón II. Panorama nacional. Análisis de los recursos genéticos disponibles a México. Soc. Mex. Fitog. 385-387 pp. [ Links ]

Robles, S. R. 1985. Capítulo II. Cultivo del algodón (Gossypium hirsutum L.). In: producción de oleaginosas y textiles. Segunda Edición. Ed. Limusa. México. 165-285 pp. [ Links ]

SNICS. 2012. Catálogo nacional de variedades vegetales. Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca yAlimentación (SAGARPA). México, D. F. 34 p. [ Links ]

Sunilkumar, G.; Campbell, M. L.; Puckhaber, L.; Stipanovic, D. R. and Rathore, S. K. 2006. Engineering cottonseed for use in human nutrition by tissue-specific reduction of toxic gossypol. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 103(48):18054-18059. [ Links ]

Tovar, G. M. R.; Pérez, C. M.; Obispo, Q. G.; Mijangos, J. C.; Pedraza, M. S.; Flores, M. Z.; Madrid, M. C.; Aragón, F. C.; Enríquez, J. F. Q.; Tavitas, L. F.; Tovar, B. G. y Bonilla, J. C. 2013. Logros de investigación en algodón nativo de México. Campo Experimental Valle de México. Centro de Investigación Regional del Centro. Desplegable Técnica Núm. 26. 6 p. [ Links ]

Ulloa, M.; Abdurakhmonov, I. Y.; Pérez, M. C.; Percy, R. and Stewart, J. 2013. Genetic diversity and population structure of cotton (Gossypium spp.) of the new world assessed by SSR Markers. Botany. 91(4):251-259. [ Links ]

Ulloa, M.; Stewart, J. McD.; García, E. A. C.; Godoy, S. A.; Gaytán, A. M. and Acosta, S. N. 2006. Cotton genetic resources in the western states of México: in situ conservation status and germplasm collection for ex situ preservation. Genetic Res. Crop Evol. 53:653-668. [ Links ]

Wallace, T. P.; Bowman, D.; Campbell, T. B.; Chee, P.; Gutierrez, A. O.; Kohel, J. R.; McCarty, J.; Myers, G.; Percy, R.; Robinson, F.; Smith, W.; Stelly, M. D.; Stewart, M. J.; Thaxton, P.; Ulloa, M. and Weaver, B. D. 2009. Status of the USA cotton and crop vulnerability. Genetic Res. Crop Evol. 56(4): 507-532. [ Links ]

Received: October 2015; Accepted: January 2016

text in

text in