Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

Print version ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.6 n.spe11 Texcoco May./Jun. 2015

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v0i11.798

Investigation notes

Foliage composition and digestibility of some tropical forage trees of Campeche, Mexico

1Campo Experimental La Posta-Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias. Carretera Veracruz-Córdoba, km 22.5, Medellín, Paso del Toro, Veracruz. México.

2Colegio de Posgraduados, Carretera. México-Texcoco km 36.5. Texcoco, Estado de México. México.

3Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán. Departamento de Nutrición Animal. México, D. F. México.

In order to evaluate their potential as an alternative foraging resource, the chemical composition, digestibility and antinutritional factors of Lysiloma latisiliquum, Senna racemosa , Bauhinia divaricata, Senna pendula, Albizia lebbeck, Piscidia piscipula, and Lonchocarpus rugosus, were determined. Plant material was collected from different, previously selected sites during the dry and rainy seasons. A. lebbeck showed the greatest crude protein (CP) content in the dry season (24%), while in the rainy season it was for S. pendula (21.8%). The greatest percentages of NDF (66.8) and ADF (46.2) were found in A. lebbeck in both seasons. The greatest lignin fraction was found in L. latisiliquum in the dry season (12.8%) and in L. rugosus in the rainy season (25.4%). The trypsin inhibitor was found in all species, and hemagglutinins in L. latisiliquum and L. rugosus, but not at toxic levels. There were differences (p< 0.05) regarding in situ digestibility among the legumes in both seasons. The greatest digestibility of DM was for S. pendula (89.1 and 85.0%), and the lowest for L. rugosus (40.1 and 48%), in both seasons. It is concluded that the dry season is the better period to use these shrub legumes given nutrient availability and management strategies must be suitable for plant survival.

Keywords: antinutritional factors; Campeche; in situ digestibility; legume trees

Con la finalidad de evaluar su potencial como una alternativa de recurso forrajero, se determinó la composición química, digestibilidad y factores antinutricionales de Lysiloma latisiliquum, Senna racemosa, Bauhinia divaricata, Senna pendula, Albizia lebbeck, Piscidia piscipula y Lonchocarpus rugosus. El material vegetal fue recolectado de diferentes sitios previamente seleccionados durante las estaciones seca y lluviosa. A. lebbeck mostró la mayor cantidad de proteína cruda (PC) en la estación seca (24%), mientras que en la estación lluviosa fue S. pendula (21.8%). Las mayores porcentajes de FND (66.8%) y FAD (46.2) se encontraron en A. lebbeck en las dos estaciones, en tanto que el mayor contenido de lignina se observó en L. latisiliquum en la estación seca (12.8%) y en L. rugosus en la lluviosa (25.4%). El inhibidor de tripsina se encontró en todas las especies y hemaglutininas en L. latisiliquum y L. rugosus, pero no en niveles tóxicos. Se encontraron diferencias (p < 0.05) en la digestibilidad in situ entre las leguminosas en las dos estaciones. La mayor digestibilidad de DM se observó en S. pendula (89.1 y 85%) y la menor en L. rugosus (40.1 y 48%), en las dos estaciones. Se concluye que la estación seca es el mejor periodo para el uso de leguminosas arbustivas por su disponibilidad de nutrientes y estrategias de manejo que deben ser apropiados para la supervivencia de las plantas.

Palabras clave: Campeche; digestibilidad in situ; factores antinutricionales; leguminosas arbustivas

In Mexico, the Fabaceae family is represented by 92 genera and three sub-families: Leguminosoideae, Papilionoideae, and Caesalpinoideae, in Campeche this family has a high number of species (Zamora et al., 2011) which might be used as animal feed. To be viable as a foraging resource, the legumes need to have nutritional characteristics that equal, or surpass protein content, and digestibility of other plants traditionally used as forage. The objective of this work was to determine the chemical composition, antinutritional factors and in situ digestibility of seven tree legumes of Campeche, Mexico.

Plant material was collected in the state of Campeche, in the municipalities of Edzna, China, Nueva Esperanza, and Campeche. The collection time of the material was the same for all species: rainy season (June-October) and dry season (March-May).

The studied species included: Lysiloma latisiliquum (L.) Benth., Bauhinia divaricata L., Senna racemosa (P. Mill.) Irwin et Barneby, S. pendula (Willd.), Albizia lebbeck (L.) Benth, Piscidia piscipula (L.) Sarg. and Lonchocarpus rugosus Benth. subsp. rugosus. Crude protein (CP), ash (AOAC, 2005), neutral detergent fiber (NDF), acid detergent fiber (ADF), and lignin (Van Soest et al., 1991), were determined. The following antinutritional factors were also analyzed: trypsin inhibitor (Kakade et al., 1974), saponins (Monroe et al., 1952), hemagglutinins, through the dilution technique (Jaffe et al., 1974), and ureasic activity (AOAC, 2002).

In situ digestibility of dry matter was evaluated (Orskov and McDonald, 1979), using nylon bags (10 x 20 cm) with porosity 52 ± 10 mm, in which were placed 5 g of the sample (DM). Three cannulated Holstein cows, mean body weight of 450 kg, were used. Incubation times were 0, 4, 8, 16, 24, 48, and 72 h. The bags were later rinsed five times with running water for one minute until water was clear and dried in an air stove at 55 °C. In situ digestibility was calculated as the amount of disappeared DM.

Data were analyzed as repeated measurements using the PROC MIXED procedure of SAS (SAS, 2002) for a completely randomized design. Means were compared by Tukey test (p< 0.05).

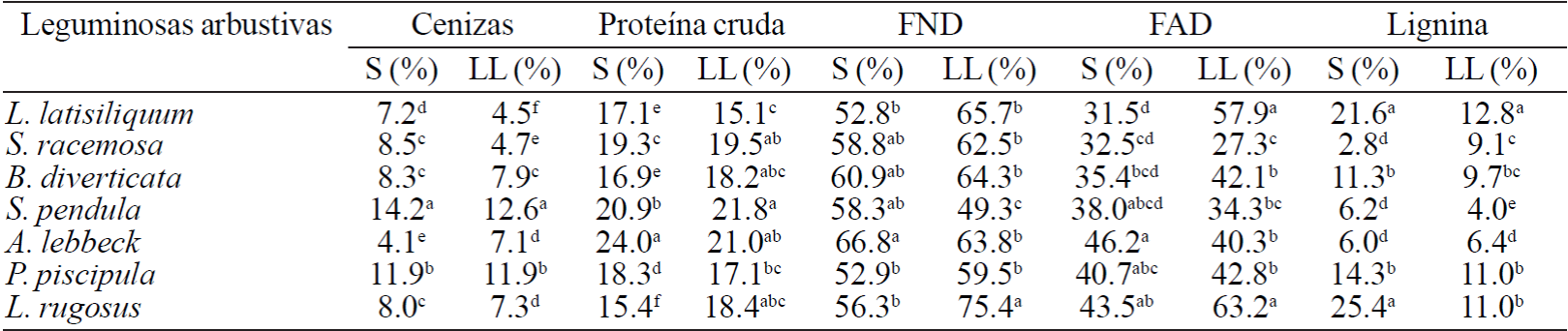

Differences (p ˂ 0.05) were seen among the studied legumes regarding ash content in the dry season. The greatest values were observed in S. pendula and P. piscipula (14.2 and 11.9%); these species also showed the highest concentrations in the rainy season (Table 1). A. lebbeck and S. pendula showed the highest percentages of CP (p˂ 0.05) in the dry and rainy seasons. The highest NDF value in the dry season was for A. lebbeck (66.8%), followed by B. divaricate (60.9%), S. racemosa (58.8%), and S. pendula (58.3%). In the rainy season, the highest was for L. rugosus (75.4%). On the other hand, the highest ADF value in the dry season was for A. lebbeck (46.2%) followed by L. rugosus (43.5%) and P. piscipula (40.7%). In the rainy season, L. rugosus and L. latisiliquum showed the highest values (63.2 and 57.9%, respectively), while S. racemosa had the lowest value (27.3%).

Table 1 Composition of tree legumes collected in Campeche, Mexico during the dry and rainy season in DM basis.

S= estación seca; LL= estación lluviosa. Los valores en la misma columna con diferente letra son las diferencias entre ellos (p< 0.05).

The highest lignin content (p˂ 0.05) in the dry season was for L. rugosus (25.4%), while in the rainy season was for L. latisiliquum (12.8%). The results in this study for A. lebbeck are similar to those obtained by Rodriguez et al. (2005) for ash, ADF and NDF, with slight variations, possibly because of the different re-budding ages used. López et al. (2008) have reported the following values for P. piscipula harvested in Quintana Roo: 12.6% CP; 50% FDN; 34.6% FDA and 17.2 for lignin. With the exception of the lower concentration of CP observed by these researchers, the values are similar to those found in the present study. The lignin content of the plants in this study is within the normal values for tropical shrub legume species, as mentioned by Camero et al. (2001).

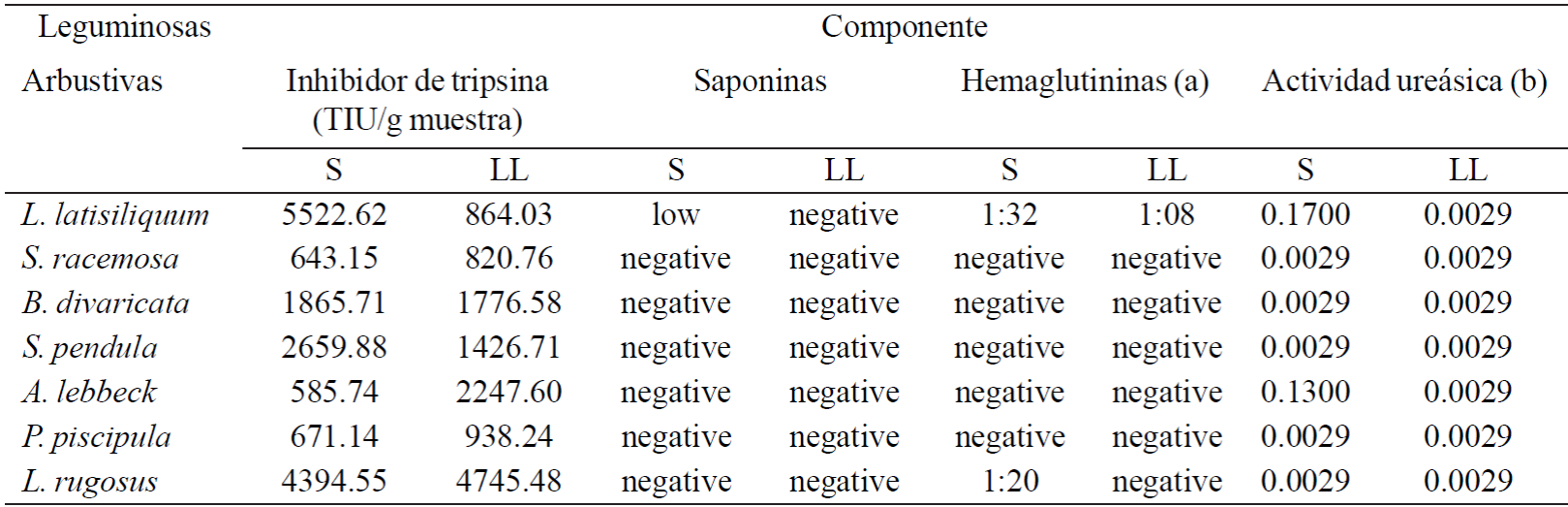

In the rainy season, most of the evaluated species showed a variation in the concentration of the trypsin inhibitor, with high values in L. rugosus, S. pendula and B. divaricata, and the lowest in S. racemosa. In the dry season, they were surpassed by L. latisiliquum, L. rugosus, and S. pendula; on the other hand, the lowest values were observed in A. lebbeck and S. racemosa (Table 2). This compound results in the decrease of the trypsin activity, causing growth problems and pancreas hypertrophy. However, ruminants are less affected than non-ruminants because trypsin inhibitors are degraded slowly in the rumen (Fuller, 2004).

Table 2 Antinutritional factors in tree legumes collected in Campeche, Mexico.

S= estación seca; LL= estación lluviosa. TIU= unidades de inhibidor de tripsina, a= maxima dilución que produce aglutinación en 1 h, b= aumento en unidades de pH.

Saponin was not present in the legumes studied, with the exception of L. latisiliquum which content was low in the dry season however this concentration is not harmful for ruminants. Hemagglutinins were present in L. latisiliquum in both rainy and dry season and in L. rugosus in the dry season. The ureasic activity can be harmful, since it produces ammonia when urea is used as a supplement values of 0.11 units or less are considered aceptable (Arelovich, 2008). The values observed in this study were lower to this amount, except for L. latisiliquum and A. leebeck in the dry season.

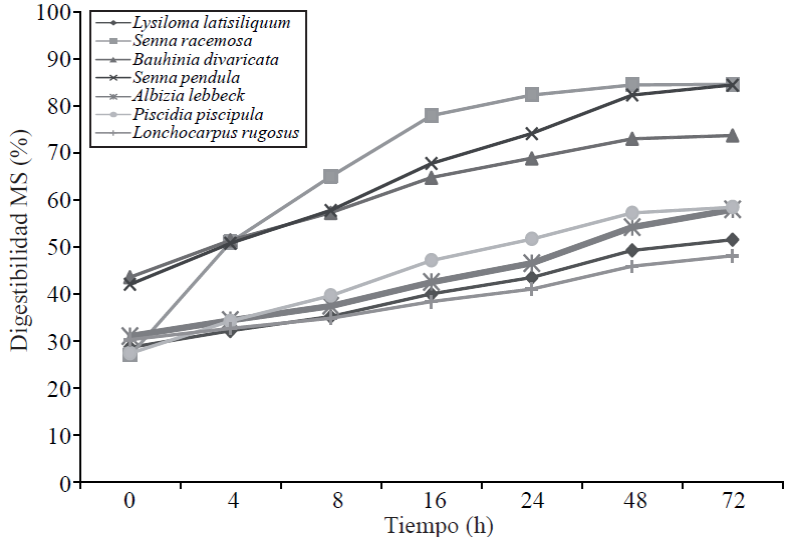

In situ digestibility of the forage sampled in the rainy season showed significant differences (p< 0.05) among species in the first four hours of incubation, with the highest values for S. pendula (59.1%) and S. racemosa (46.2%), while L. rugosus showed the lowest value (32.1%; Figure 1).

Figure 1 In situ DM digestibility of tree legumes collected in the rainy season in Campeche, Mexico.

S.pendulaandS.racemosabehavedsimilarlyduringincubation, with higher values at 72 h (89.1 and 88%, respectively), followed by B. divaricata and P. piscipula (67.1 and 60.2%, respectively). The specie with the lowest digestibility was L. rugosus with 32.0 and 40.1% at 4 and 72 h incubation.

Forage collected in the dry season showed differences (p< 0.05) among species, being S. racemosa, B. divaricata, and S. pendula statistically similar with 51.1% at 4 h incubation, but different to A. lebbeck and P. piscipula with 34% and these last ones similar to L. rugosus and L. latisiliquum (Figure 2). As incubation time passed, the first three species kept the highest digestibility, up to 72 h. In both the dry and rainy seasons, the lowest value was for L. rugosus, with 48.1% digestibility of DM at 72 h.

In situ digestibility of guacimo (Guazuma ulmifolia Lam.) has been reported as 77.7% (Pinto et al., 2004). It is considered a forage species because of both its acceptability and its high digestibility. Its digestibility value is near to those found in this study for S. pendula and B. divaricata at 24 h incubation. Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit is a legume used in animal production systems, which has shown, in the rainy season, a digestibility at 48 h of 66.2% and at 72 h, 68.0% (Sánchez et al., 2008). These values are similar to those obtained for B. divaricata at 48 and 72 h, as well as for P. piscipula at 72 h.

Values above 60% after 20 h of incubation have been reported for Leucaena leucocephala (Razz et al., 2004). This value is comparable with the results obtained for B. divaricata and S. pendula. The digestibility reported for Gliricidia sepium (Olivares et al., 2005) was 36, 50, and 70% at 12, 24, and 48 h, similar to L. rugosus, mainly at 16 and 24 h (36.1 and 43% digestibility), respectively.

Conclusions

A high in situ DM digestibility was found for S. racemosa, S. pendula, B. divaricata, and P. piscipula, regardless of the season, being a greater availability of nutrients in the dry season. Among the determined antinutritional factors, trypsin inhibitor was the one found in greater proportion, but not at levels which might be toxic, while the concentration of other antinutritional factors analyzed was less or not existent. Therefore, the legumes evaluated can be used in grazing systems with moderate intake or as protein banks.

Literatura citada

AOAC (Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC). 2005. International. 18th Ed. AOAC International, Gaithersburg, Maryland. [ Links ]

AOAC (Official Methods of Analysis). 2002. 17th Ed. Association of Agricultural Chemists, Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Arelovich, H. M. 2008. Elementos minerales. Su impacto en la fermentación ruminal. Rev. Argent. Prod. Anim. 28:235-253. [ Links ]

Camero, A.; Ibrahim, M. and Kass, M. 2001. Improving rumen fermentation and milk production with legume-tree fodder in the tropics. Agroforest. Syst. 51:157-166. [ Links ]

Fuller, M. F. 2004. The encyclopedia of farm animal nutrition. CABI, Wallingford, UK. [ Links ]

Jaffé, L. A.; Werner, G. and González, I. D. 1974. Isolation and partial characterization of bean phytohemaglutinins. Phytochem. 13:2685-2693. [ Links ]

Kakade, M. L.; Rackis, J. J.; McGhee, J. E. and Puski, G. 1974. Determination of trypsin inhibitors activity of soy-products. A collaborative analysis of an improved procedure. Cereal Chem. 51:376-382. [ Links ]

López, H. M. A.; Rivera, L. J. A.; Ortega, R. L.; Escobedo, M. J. G.; Magaña, M. M. A.; Sanginés, G. R. y Sierra, V. A. C. 2008. Contenido nutritivo y factores antinutricionales de plantas nativas forrajeras del Norte de Quintana Roo. Téc. Pec. Méx. 46:205-215. [ Links ]

Monroe, E. E.; Wall, E. and Rolland, M. L. 1952. Detection and estimation of steroidal sapogenins in plant tissue. Anal. Chem. 8:1337-1341. [ Links ]

Olivares, P. J.; Jiménez, G. R.; Rojas, H. S. y Martínez, H. P. A. 2005. Uso de las leguminosas arbustivas en los sistemas de producción animal del trópico. Revista Electrónica de Veterinaria. 6(5)234-243. http://www.veterinaria.org/revistas/redvet/n050505.html. [ Links ]

Orskov, E. R. and McDonalds, I. 1979. The estimation of protein degradability in the rumen from incubation measurements weighted according to rate of passage. J. Agric. Sci. Camb. 92:499-503. [ Links ]

Pinto, R.; Gómez, H.; Martínez, B.; Hernández, A.; Medina, F.; Ortega, L. y Ramírez, L. 2004. Especies forrajeras utilizadas bajo silvo-pastoreo en el centro de Chiapas. AIA. 8:1-11. [ Links ]

Razz, R.; Clavero, T. y Vergara, J. 2004. Cinética de degradación in situ de la Leucaena leucocephala y Panicum maximum. Rev. Cient. FCV-LUZ. 14:424-430. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, Y.; Chongo, B.; La O, O.; Oramas, A.; Scull, I. y Achang, G. 2005. Características químicas de Albizia lebbeck y determinación de su potencial nutritivo mediante la técnica de producción de gas in vitro. Rev. Cubana Cienc. Agri. 39:313-318. [ Links ]

SAS (Statystical Analysis Systems). 2002. SAS Proceeding Guide: Versión 9.0. SAS Inst. Inc. Cary, NC, USA. [ Links ]

Sánchez, T.; Orskov, R. E.; Lamela, L.; Pedraza, R. y López, O. 2008. Valor nutritivo de los componentes forrajeros de una asociación de gramíneas mejoradas y Leucaena leucocephala. Pastos y Forrajes 31:271-281. [ Links ]

Van Soest, P. J.; Robertson, J. B. and Lewis, B. A. 1991. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. In: Symposium carbohidrate methodology, metabolism, and nutritional implication in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 74:3585-3597. [ Links ]

Zamora, C. P.; Domínguez, C. M. R.; Villegas, P.; Gutiérrez, B. C.; Manzanero, A. L. A.; Ortega, H. J. J.; Hernández, M. S.; Puc, G. E. C. y Puch, C. R. 2011. Composición florística y estructura de la vegetación secundaria en el norte del estado de Campeche, México. Bol. Soc. Bót. Méx. 89:27-35. [ Links ]

Received: January 01, 2015; Accepted: April 01, 2015

text in

text in