Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

Share

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

Print version ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.5 n.spe9 Texcoco Sep./Nov. 2014

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v0i9.1066

Investigation note

Characterization of white-alcatraz producers in La Perla, Veracruz

1 Colegio de Postgraduados-Campus San Luis Potosí. Iturbide 73. 78621. Salinas de Hidalgo, San Luis Potosí, S.L.P., México.

2 Colegio de Postgraduados-Campus Montecillo. km 36.5 Carretera México-Texcoco. 56230, Montecillo, Texcoco, Estado de México. México. (nadia.torres@colpos.mx; tlibia@colpos.mx).

In Mexico, the white alcatraz (Zantedeschia aethiopica (L) K. Spreng) is considered a minor crop of cut flowers grown in the central region of the state of Veracruz. The aim of this study was to determine the status of the producers of alcatraz in the town of La Perla, Veracruz. The research method consisted of a survey by a questionnaire sent to a representative sample of producers in this county alcatraz. The results show that 53% of producers are people who have low levels of schooling, see no need to belong to an association, more than 80% of farmers consider it a very profitable business; have become associated with other plants alcatraz to strengthen their economy. Ongoing training on agronomic crop management is recommended to provide a comprehensive management plants, focus to combat and eradicate "soft rot", the main phytosanitary problem, coupled with the traditional system of production, lack of investment and value addition.

Keywords: Zantedeschia aethiopica; agronomic management; production; soft rot

En México, el alcatraz blanco (Zantedeschia aethiopica (L) K. Spreng) es considerado como un cultivo menor de flores de corte, cultivada en la zona centro del estado de Veracruz. El objetivo de este trabajo fue determinar la situación de los productores de alcatraz en el municipio de La Perla, Veracruz. El método de investigación consistió en la aplicación de una encuesta mediante un cuestionario dirigido a una muestra representativa de productores de alcatraz en este municipio. Los resultados muestran que 53% de los productores son personas que tienen bajo nivel de escolaridad, no consideran necesario pertenecer a alguna asociación, más de 80% de los productores lo considera un negocio poco rentable; han ido asociando el alcatraz con otras plantas para fortalecer su economía familiar. Se recomienda capacitación permanente sobre el manejo agronómico del cultivo, dar un manejo integral a las plantas, enfocarse al combate y erradicación de la “pudrición blanda”, principal problema fitosanitario, aunado al sistema tradicional de producción, la falta de inversión y agregación de valor.

Palabras clave: Zantedeschia aethiopica; producción; manejo agronómico; pudrición blanda

Flower production is one of the most widespread productive activities in rural areas. It is without exception in all agro-ecological regions of Mexico. Existing megadiversity in Mexico, does that have a great potential for this activity due to favourable weather conditions in some regions and geographical proximity to the United States of America, second largest consumer of flowers in the world (ASERCA, 2008). Species of the genus Zantedeschia in Mexico is mainly grown, Z. aethiopica (L) K. Spreng (white alcatraz) being the most important. However, there is limited knowledge on the agronomic cultivation of other species (Cruz-Castillo et al., 2008). The white alcatraz is part of the list of commercially important crops in the municipality of La Perla in the state of Veracruz; and is part of a group of highly prized plants in the domestic market (Sefiplan, 2011). Currently, there are no studies that describe in detail the agronomic practices that perform alcatraz producers in this county.

In this study was used as a tool to gather information a survey, using a questionnaire focused on alcatraz producers. To select the locations where the surveys would apply, we consulted with the Office of Agricultural Development in the municipality of La Perla; the sample size based on a population of 1200 alcatraz producers was calculated. Finally, to determine the size of the sample the following equation, according to was used Trejo et al. (2011).

Where: n= number of surveys performed, N= size of the population d= desired accuracy.

The total number of polls producer was 41, using a precision of 0.15 and a margin of error of 5%. The questions included in the questionnaire were coded so that responses could be captured in a spreadsheet in Excel and well testing. This included questions concerning the characteristics of the informant, and the production system, production infrastructure, marketing, production costs, organization, financing, training and government support for the production of alcatraz.

The participation of rural agents involved in the production of alcatraz, shows that the gender ratio is equal to a ratio of 50:50 (Figure 1A). As far as education is concerned, the recorded profile (Figure 1B) indicated that just over half of the farmers studied for the primary level, and most of them not finished.

Figure 1 Proportion of gender (A) and profile of education (B) of the sample of producers of alcatraz at La Perla, Veracruz.

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO, 2013), considers the participation of women in agriculture and the closing of the gender-gap, as important benefits to society in order to increase agricultural productivity. Also, the UNESCO (2011) believes that education is a key to human development and poverty alleviation factor. The accumulated evidence and theories of development have shown that education is a powerful tool for economic, social and cultural change (Atchoarena and Gasperini, 2004). Complete at least 12 years of schooling (primary and secondary) in most countries, is the minimum educational capital to achieve wellness and associate to greater than 80% probability of getting a job with a better income (CEPAL, 2006). In Mexico, people aged 15 and older are 8.6 grades of schooling on average, which means a little bit more than second grade (INEGI, 2010).

An important indicator of progress in a country is the educational level of its population, according to UNESCO (2011), reached the highest level occurs in the population 25 years of age in Latin and Caribbean. La Perla, alcatraz producers have on average 41 years old, indicating that it is still an actively productive population that still is being devoted to agriculture. In addition, younger farmers are those with completed primary education (Figure 2).

UNESCO (2010) states that, the education is a key axis of population development. With it is possible to improve the social, economic and cultural conditions of the countries. Rising educational levels of the population is associated with improvement of other key factors of development and welfare, such as productivity, social mobility, poverty reduction, building citizenship and social identity and, ultimately, strengthening social cohesion; likewise, it is recognized that primary education is totally inadequate to fully participate in civic life and to enter the labour market.

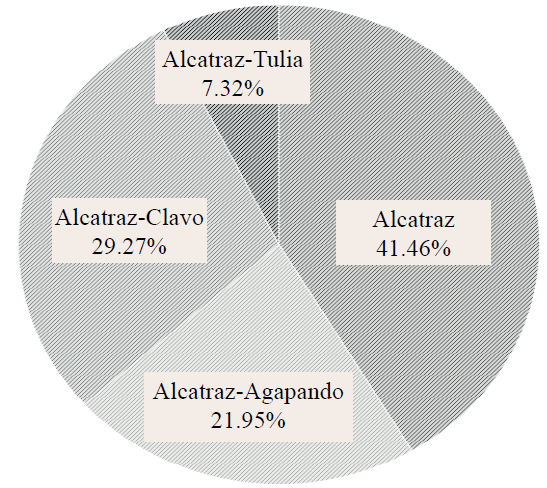

The production system of Alcatraz in this county is characterized by preserving the culture associated with other flowers (agapando, Agapanthus africamus); or foliage (clovo, Pittosporum sp.; tullia, Thuja occidentalis ); established exclusively open. The results show that the producers are looking for new options for income, while cultivating Alcatraz at the same time. In Figure 3, we show that over 50% of the cultivated surface alcatraz is mainly associated with foliage.

According Chahin (2012), the cultivation of ornamental foliage is now a new alternative business, as more and more different varieties of branches and leaves that provide a smoothing and contrast the effect arrangements are used. That is why, now this type of ornamental product is a real alternative to incorporate the production systems that complement the business of cut flowers. In addition, we add new species and thereby increase the range of supply in the market.

Of the surveyed sample, producers sowed alcatraz low temporal system; mainly during the months of May and June; so that maximum production is concentrated from October to November, making two cuts feasible on a week. However, only 60% of producers makes plant renovation, on average every 10 months. Other producers take up to two years to renew their land plants. Plants planted, mostly obtained from the same locality (93%) at a price of $2.00 pesos per plant.

The economic difficulties have a steady income; have caused different reactions in producing related directly or indirectly to the alcatraz, so that the producer has relegated cultivation and crop management associated with an issue of importance with consequent better decreased productivity and quality of the flower. A major recoverable in a policy of encouraging feature is that producers associated flowers (alcatraz) with foliage to increase income consider it an unprofitable activity. Despite the problems of low productivity, floriculture at the household level is an important matter. Relate it to family farming food production, is not thought to be the best in this case.

Regarding employment generation, only half (56.1%) of temporary workers during harvest contract manufacturers (October-November). On average during this period a worker receives a payment of $50.00 pesos per day, slightly below the minimum wage.

According to that reported by Soto et al. (2007), the United Nations (UN), suggests that the reduced land base and other private assets (including human, physical, financial capital and access to technology), which is generated in different environments (defined by based on natural resources and access to public goods and services), the optimal strategy of a given household, is that of self-employed in their own plot/ farm or engage in other (agricultural and non-agricultural) activities not related to their own plot.

In addition, producers do not make any fertilization in any stage of the crop, receive technical advice and do not have the infrastructure; only use hand tools such as machetes and hoes. Soto et al. (2007) emphasizes the importance of access to financial services as a strategy that provides opportunities to improve technologies and can be instrumental in the diversification of income-generating activities in the rural sector. If we have less access to agricultural extension services, access that is more difficult and use other resources (land, credit and fertilizers). These factors also impede adoption of new technologies (FAO, 2011).

One of the main problems of growing alcatraz is a disease caused by the bacterium Erwinia carotovora known as soft rot. This disease is favoured by excessive and permanent conditions of soil moisture. In contrast, water stress leads to uneven germination of bulbs, poor growth and flowering, short and weak flowering stems. Also, sudden fluctuations in soil moisture cause cracking of flowering stems (Gómez, 2009). In Figure 4, the damage causes soft rot during the crop cycle, which comes in three phenological stages (planting, growing and flowering). The lower severity occurs during planting, with 4.9% loss of the seeded plants; in the growth stage, the losses are 43.9% and finally the flowering stage, 51.2% of the total sown plants is lost, and in the latter stage is where the greatest loss occurs.

Figure 4 Damage caused by Erwinia carotovora, by phenological stage in Alcatraz cultivation in La Perla, Veracruz.

Ignorance about the agronomic management and rhizomes susceptibility to attack by Erwinia carotovora, coupled with high levels of soil moisture have become a barrier to the increase in cultivated areas (Gómez, 2009). As a result, production of alcatraz has been diminished, since on average seven per planted dozens of booby task are obtained (Table 1).

Table 1 Production of alcatraz obtained in 2011 in La Perla, Veracruz.

| (%) de productores | Decenas/tarea cosechada * | (%) de productores | Decenas/tarea cosechada |

| 9.76 | 2 | 4.88 | 8 |

| 14.63 | 3 | 4.88 | 10 |

| 17.07 | 4 | 2.44 | 12 |

| 19.51 | 5 | 2.44 | 15 |

| 12.2 | 6 | 7.32 | 20 |

| 2.44 | 7 | 2.44 | 25 |

* 625 m2.

Literatura citada

Apoyos y Servicios a la Comercialización Agropecuaria (ASERCA)-Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación (SAGARPA). Regional peninsular. La Floricultura. 2008. http://www.aserca.gob.mx/artman/uploads/boletin. [ Links ]

Atchoarena, D. y Gasperini, L. 2004. Educación para el desarrollo rural: hacia nuevas respuestas de política. Estudio conjunto realizado por la FAO y la UNESCO. Roma, Italia. 23 p. [ Links ]

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). 2006. Panorama social de América Latina. División de Desarrollo Social y División de Estadística y Proyecciones Económicas de la CEPAL. Naciones Unidas. Santiago de Chile. 430 p. [ Links ]

Chahin, A. G. 2012. Experiencia en la región de la Araucanía. Cultivo de follajes ornamentales: una alternativa para la floricultura del Sur. Instituto de Investigaciones Agropecuarias (INIA), Centro Regional Carillanca. Boletín técnico Núm. 238. 143 p. [ Links ]

Cruz-Castillo, J. G.; Torres, L. P.; Albores, G. M.; y González, M. L. 2008. Lombricompostas y apertura de la espata en postcosecha del alcatraz "Green Goddess" (Zantedeschia aethiopica (L) K. Spreng) en condiciones tropicales. Rev. Chap. Ser. Hort. 14(2):207-212. [ Links ]

Organización de la Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación (FAO). 2011. El estado de la agricultura y la alimentación. Roma, 2011. ISBN 978-92-5-306768-8. 171 p. [ Links ]

Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura (FAO). 2013. Política de igualdad de género de la FAO. Alcanzar las metas de seguridad alimentaria en la agricultura y el desarrollo rural. Roma, Italia. 36 p. [ Links ]

Gómez, P. S. 2009. Absorción de nutrientes de Zantedeschia elliottiana (calla lily) en diferentes estados fenológicos como punto de partida para la determinación de requerimientos nutricionales del cultivo en condiciones del eje cafetero Colombiano. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI). 2010. http://cuentame.inegi.org.mx/poblacion/escolaridad.aspx?tema=P. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Finanzas y Planeación (SEFIPLAN). 2011. Cuadernillos Municipales, Orizaba. Sistema de Información Municipal. Gobierno del estado de Veracruz. 11 p. [ Links ]

Soto, B. F.; Rodríguez, F. M. y Falconi, C. 2007. Políticas para la agricultura familiar en América Latina y el Caribe. Organización de las Naciones Unidad para la Agricultura y la alimentación. Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (BID). Oficina Regional de la FAO para América Latina y el Caribe. Santiago, Chile. 145 p. [ Links ]

Trejo T., B. I.; Ríos, C. I. y Figueroa, S. B. 2011. Análisis de la cadena de valor del sector ovino en Salinas, San Luis Potosí, México. Agric. Soc. Des. 8(2):249-260. [ Links ]

Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura (UNESCO). 2010. Educación, juventud y desarrollo. Acciones de la UNESCO en América Latina y el Caribe. Documento preparado para la conferencia Mundial de la Juventud. León, Guanajuato, México. 43 p. [ Links ]

Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura (UNESCO). 2011. Everyone has the right to education. 32 p. [ Links ]

Received: April 2014; Accepted: July 2014

![Seedlings growth rates of lulo (Solanum quitoense [Lamarck.]) In organic substrates](/img/en/prev.gif)

text in

text in