Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Agricultura, sociedad y desarrollo

Print version ISSN 1870-5472

agric. soc. desarro vol.15 n.2 Texcoco Apr./Jun. 2018

Articles

Productive Capacity of Pleurotus Ostreatus Using Dehydrated Alfalfa as Supplement in Different Agricultural Substrates

1Centro de Agroecología, Instituto de Ciencias; Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. México. (damianhuato@hotmail.com).

2Maestria en Ciencias Ambientales, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. México.

3Centro de Investigaciones en Ciencias Microbiológicas, ICUAP-Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. México.

4Instituto de Ciencias Biológicas; Universidad Autónoma de Morelos. México.

5Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia-Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. México.

The study had the objective of supplementing with different proportions of dehydrated alfalfa (Medicago sativa L) the different agricultural substrates most frequently used in the production of the “oyster mushroom” fungus from the municipality of Tetela de Ocampo, Puebla, México. Seventeen treatments were performed, including 5 controls for each substrate used in a random experimental design in blocks, with a total of 85 production units. The substrates were inoculated and after 28 days of incubation, these presented 90 % of mycelium colonization of the CP-50 strain of Pleurotus ostreatus and after 121 days the experiment was finished by obtaining three harvests for each treatment. The best combination for the production of oyster mushrooms was the “PT-3Al” treatment with 17.94 kg, the treatment that obtained the lowest production was “Al” with 3.51 kg. The lowest biological efficiency (BE) is for bean hay residue with 46.84 %, in addition to the most abundant substrate of the region, “maize stubble”, increasing its BE from 64.30 to 120.91 % with a supplement of 3 kg of alfalfa and a biodegradation rate of 64 %. The use of dehydrated alfalfa as supplement in the conventional substrates increases the production of the CP-50 strain under controlled conditions.

Key words: oyster mushroom; production; agricultural residues; biological efficiency and biodegradation rate

La investigación tuvo como objetivo suplementar con distintas proporciones de alfalfa (Medicago sativa L) deshidratada los diferentes sustratos agrícolas más utilizados en la producción del hongo “seta” provenientes del Municipio de Tetela de Ocampo, Puebla-México. Se realizaron 17 tratamientos, incluyendo 5 testigos por cada sustrato empleado en un diseño experimental de bloques al azar, con un total de 85 unidades de producción. Los sustratos fueron inoculados y después de 28 días de incubación, éstos presentaron un 90 % de colonización del micelio de la cepa CP-50 de Pleurotus ostreatus y al término de 121 días se finalizó el experimento obteniendo tres cosechas por cada tratamiento. La mejor combinación para la producción de setas fue el tratamiento “PT-3Al” con 17.94 kg, el tratamiento que obtuvo la producción más baja fue “Al” con 3.51 kg. La menor Eficiencia biológica (EB) es para el residuo paja de frijol con 46.84 %, además el sustrato más abundante de la región “rastrojo de maíz” incrementó su EB de 64.30 a 120.91 % con un suplemento de 3 kg de alfalfa y una tasa de biodegradación de 64 %. La utilización de alfalfa deshidratada como suplemento en los sustratos convencionales, aumenta la producción de la cepa CP-50 en condiciones controladas.

Palabras claves: seta; producción; residuos agrícolas; eficiencia biológica y tasa de biodegradación

Introduction

The global production of cultivated edible mushrooms has increased more than 30 times since 1978; by 2012, more than 31 million tons were recorded, generating 20 000 million dollars, with a per capita consumption of mushrooms that exceeds the 4.70 kg annually (Chang and Wasser, 2012; FAO, 2014).

China is the main producer of cultivated mushrooms in the world; by the year 2013 it produced more than 30 000 million kg of fresh mushrooms, representing 87 % of total production, while the United States and other countries produced around 3 100 million kilos. It should be mentioned that in the United States production has increased around 11.7 % in the last 10 years, generating 423.2 million kg in 2015 (Wu et al., 2013; Cunha and Pardo, 2017).

México is the largest producer in Latin America, generating around 80.8 % of total production for the region, followed by Brazil (7.7 %) and Colombia (5.2 %), rating as number 13 globally (Romero-Arenas et al., 2015). It should be highlighted that by the year 2011, a production of 62 374 tons of fresh mushrooms was obtained, increasing every year (Martínez-Carrera et al., 2012). In addition, the production of oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus spp) in México has increased in the last 10 years; currently, it corresponds to a proportion of 4.76 % of total production (Martínez-Carrera et al., 2016). It should be mentioned that the Pleurotus genus is the second most cultivated mushroom; it constitutes approximately 19 % of the world production, while Auricularia contributes around 17 %. The other genera, Agaricus and Flammulina, are responsible for 15 and 11 % of the volume, respectively (Suárez and Nieto, 2013; Royse et al., 2016).

Oyster mushroom production represents an accessible alternative to increase food obtainment with high protein value; P. ostreatus represents a food with 350 calories compared to red meat, which only contains 150 calories or fish that contains 101 (Romero-Arenas et al., 2010). Currently, biotechnology applied to edible mushroom cultivation allows obtaining large productions in relatively small spaces, representing an agroindustry of great socioeconomic importance, due to the use of agroindustrial and agricultural residues, as well as an industry that generates employment (Romero-Arenas et al., 2010; Fanadzo et al., 2010; Adebayo and Martinez-Carrera, 2015). This is why more than 40 % of the municipalities of the state of Puebla produce edible mushrooms such as champignon (A. bisporus), shiitake (L. edodes) and oyster mushroom (P. ostreatus) [Medel et al., 2011].

The production of oyster mushrooms presents a promising biotechnological potential that covers a multitude of application fields (Andrino et al., 2011). During years, oyster mushroom cultivation has been considered important for the family economy; in addition, there is an interest to improve the cultivation technology, which has gained considerable attention in recent years (Akinyele et al., 2012). Therefore, new technologies need to be used to take advantage of the agricultural byproducts for the cultivation of P. ostreatus, knowing that more than 70 % of the agricultural residues are discarded into the environment, generating damages in the long term and being wasted in agricultural zones. In this sense, taking advantage of these wastes as inputs for the cultivation of oyster mushrooms represents an economic activity to generate a food rich in nutrients at low production costs, obtained from the fermentation of agricultural residues from rural regions (López et al., 2008; Romero-Arenas et al., 2010).

Alfalfa cultivation in México has used in the last 10 years an average of 376 182.26 annual hectares under irrigation conditions, while the rainfed modality reached 1 404.76 hectares, representing only 0.37 % of the total surface of this crop. The main producing states are: Guanajuato, Chihuahua, Hidalgo, Baja California, Coahuila, San Luis Potosí, Sonora and Puebla, representing as a whole 73 % of the total national surface sown, with a production in green of 20 359 316.08 million tons and a value of 5 707 422.75 million pesos for 2015. Puebla is one of the nine principal alfalfa producers in the whole country, with approximately 18 717.50 thousand hectares sown in the regions of Tehuacán, Tecamachalco, Libres and Cholula, contributing 88.33 %, with a yield of 5 126.5 ton/ha (SAGARPA-SIAP, 2015).

The strategy proposed by this study represents the potential for the cultivation of the P. ostreatus CP-50 strain, using residues from the region of Sierra Norte in the state of Puebla, such as: wheat, maize, barley and bean, complemented with different concentrations of dehydrated alfalfa, increasing the amount of raw protein and dry matter from the substrate (agricultural byproducts), thus increasing the biological efficiency of the crop, as well as the yield for the production of the oyster mushroom under controlled conditions.

Materials and Methods

The study was performed in the experimental plant for research in edible oyster mushroom production in the Agroecology Center, belonging to the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla (BUAP) in the municipality of Tetela de Ocampo, located on the Sierra Norte in the state of Puebla, México, whose geographic limits are: 19° 43’ 00” and 19° 57’ 06” of latitude North and 97° 38’ 42” and 97° 54’ 06” of longitude West. It borders north with Cuautempan and Tepetzintla, south with Ixtacamaxtitlán, west with Xochiapulco and Zautla, and east with Aquixtla, Zacatlán and Ixtacamaxtitlán (Enciclopedia de los municipios de Puebla, 2015).

The CP-50 strain of P. ostreatus (Jacq. ex Fr.) Kumm., used in the study, comes from the Genetic Resources Center of Edible Mushrooms (Centro de Recursos Genéticos de Hongos Comestibles, CREGENHC) of Colegio de Postgraduados and is deposited in the Edible Mushroom Strain Collection of the Puebla Campus. The strain is maintained in a medium made up of potato dextrose agar (PDA) Bioxon brand, at 28 °C (Sobal et al., 2007).

For the inoculation of the CP-50 strain, various agricultural residues were used, which were the following: wheat hay (Triticum aestivum L.), barley hay (Hordeum vulgare L.), bean straw (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), maize stubble (Zea mays L.) and alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.), which were obtained in the region of Tetela de Ocampo, Puebla, México. In the laboratory, the materials were fragmented mechanically into portions of 1 to 3 cm of length; in the case of alfalfa, it was dehydrated in a drying stove (50 °C) until reaching constant weight and water loss above 3% (Buswell et al., 1993).

The substrates were pasteurized in hot water at 80 °C/1 h.; after this time of pasteurization, they were transported to the sowing area to allow their cooling and dripping of excess moisture (approximately 30 minutes) [Romero-Arenas et al., 2010]. Later, sowing was performed (inoculation) and transparent plastic bags of 40x60 cm were prepared, with a capacity of 6 kg (humid weight) of each substrate used. The experiment was designed in random blocks, which had 17 treatments with five repetitions for each one and five control groups (Table 1).

Table 1 Treatments evaluated, as well as their corresponding description and code for their identification.

| Código | Descripción de los tratamientos |

|---|---|

| PT | |

| PC | |

| RM | Grupo Testigo (6 kg) sustrato |

| PF | |

| Al | |

| PT-2 Al | Paja de trigo (4 kg) + 2 kg de alfalfa deshidratada |

| PC-2 Al | Paja de cebada (4 kg) + 2 kg de alfalfa deshidratada |

| PF-2 Al | Pajilla de frijol (4 kg) + 2 kg de alfalfa deshidratada |

| RM-2 Al | Rastrojo de maíz (4 kg) + 2 kg de alfalfa deshidratada |

| PT-2.5 Al | Paja de trigo (3.5 kg) + 2.5 kg de alfalfa deshidratada |

| PC-2.5 Al | Paja de cebada (3.5 kg) + 2.5 kg de alfalfa deshidratada |

| PF-2.5 Al | Pajilla de frijol (3.5 kg) + 2.5 kg de alfalfa deshidratada |

| RM-2.5 Al | Rastrojo de maíz (3.5 kg) + 2.5 kg de alfalfa deshidratada |

| PT-3 Al | Paja de trigo (3 kg) + 3 kg de alfalfa deshidratada |

| PC-3 Al | Paja de cebada (3 kg) + 3 kg de alfalfa deshidratada |

| PF-3 Al | Pajilla de frijol (3 kg) + 3 kg de alfalfa deshidratada |

| RM-3 Al | Rastrojo de maíz (3 kg) + 3 kg de alfalfa deshidratada |

PT: Wheat, PC: Barley, RM: Maize PF: Bean, Al: Alfalfa.

The bags were sown homogenously with the “seed” previously prepared in a 1:10 rate. The samples sown were incubated at room temperature (26±2 °C); when the mycelium of the mushroom colonized the substrates completely and showed the appearance of primordia, the bags were transported to the fructification room where controlled conditions were promoted with regards to moisture (70 to 80 %), temperature (18 to 25 °C), indirect day light, and air extraction for 1 h, every 8 h (Garzón et al., 2008).

The production data that were recorded were: fresh weight of mushrooms collected per harvest, biological efficiency [BE=Fresh weight of the mushroom harvested (g)/Dry weight of the substrate (g)]x100 (Tchierpe and Hartman, 1977; Salmones et al., 1997), production rate (PR=BE/time that passed since inoculation until the last harvest) (Reyes et al., 2004) and biodegradation rate (BR=Dry weight of the initial substrate - Dry weight of the final substrate / Dry weight of the initial substratex100). In addition, the productivity was expressed in terms of grams of fresh mushrooms per production cycle (Romero-Arenas et al., 2010).

The SPSS Statistics package, version 17 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences), was used. The data obtained were processed with the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and later Tukey’s multiple comparison test (p≤0.05) was used to determine the differences between treatments.

To determine dry matter, raw protein, ash, ethereal extract, neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and acid detergent fiber (ADF), the official proximal chemical analysis methods were followed (A.O.A.C., 1980; Franco, 1990). The substrates were ground with the help of a mill using mesh No. 20; later, 1 and 2 g were used, depending on the substrate and the analysis to be performed.

Results and Discussion

Total production of CP-50

The production of the P. ostreatus CP-50 strain in the treatments evaluated was done according to the methodology described previously and lasted 121 days, since sowing of the mycelium in Petri dishes until obtaining the third harvest. Cedano et al. (1993) reported that P. ostreatoroseus began fructification after 31 days of incubation and 60 days of production; similar results to this research, where the CP-50 strain presented its first fructification between 38 days in most of the treatments and up until 73 days of production. Regarding the harvest period, Mora (2004) reported a harvest period of five weeks, using the strain (HEMIM-50) of P. ostreatus on wheat hay; Gómez (2004) mentions an average period of six weeks, with the same strain and in the same substrate. The harvesting period for the CP-50 strain in this study was between six and seven weeks, which agrees with what was reported by Gómez (2004).

The cultivation cycle of the P. ostreatus CP-50 strain ranged between 100 days and 121 days, with a mean of 38 days of colonization, plus 45 days of fructification. In his study, Aguirre (2000) reported a cultivation cycle of 119 days (32 days of colonization, plus 84 days of fructification); Gómez (2004) reported a cultivation cycle of 88 days for the strain (HEMIM-50) of P. ostreatus, 53 days of colonization, plus 35 days of fructification. Vernero et al. (2010) reported a cultivation cycle of 104 days for P. ostreatus in wheat hay substrate, similar results to those obtained in this research study (Table 2).

Table 2 Duration by stages of the cultivation cycle of the P. ostreatus CP-50 strain.

| Etapa | Duración en días |

|---|---|

| Crecimiento del micelio en cajas Petri | 10 |

| Crecimiento del micelio en los Masters | 18 |

| Obtención de la semilla | 20 |

| Colonización de la semilla en los diferentes tratamientos | 28 |

| Fructificación de la primera cosecha | 10 |

| Fructificación de la segunda cosecha | 15 |

| Fructificación de la tercera cosecha | 20 |

| Total | 121 |

To quantify the fresh weight of the sporocarps produced, three harvests were carried out in a lapse of 45 days. The highest yield in fresh weight was obtained in the first harvest and decreased in the next ones. In average, the first harvest obtained between 46 and 60 %; in the second cut, it was 15 to 36 %; lastly, 8 to 26 % of the total production obtained.

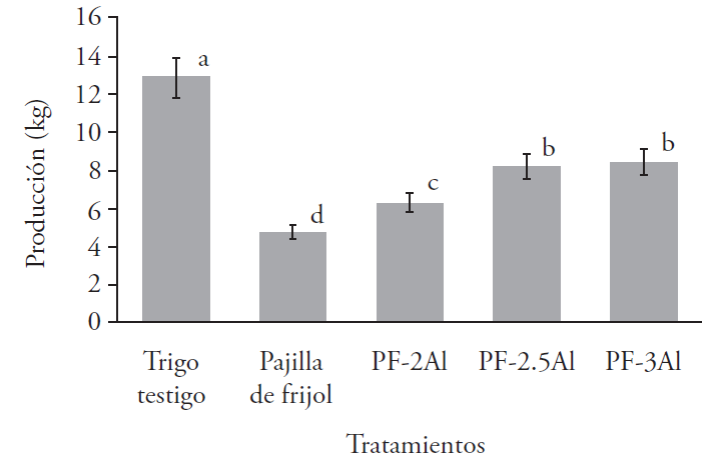

The total production in the control treatments is shown in Figure 1, where the wheat hay substrate TP reached the highest production, with a total of 12.87 kg, counting the three harvests carried out. It should be mentioned that wheat hay is the traditional substrate, on which this productive activity is carried out (Kumari and Achal, 2008). Barley hay was the one in second place with 10.22 kg, followed by maize stubble, with 6.43 kg; bean straw obtained 4.68 kg, and, lastly, dehydrated alfalfa, showing highly significant differences with the multiple range Tukey test (p≤0.05).

Different letters indicate significant differences with the multiple range Tukey test (p≤0.05).

Figure 1 Total production of the CP-50 strain of P. ostreatus in control treatments without dehydrated alfalfa.

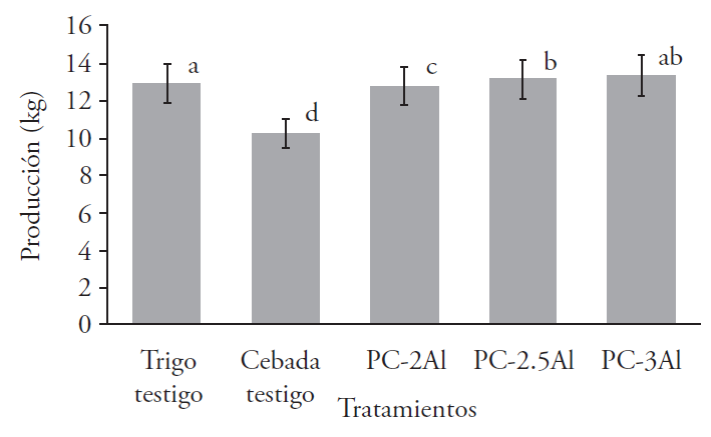

The total production obtained from the P. ostreatus CP-50 strain in barley hay supplemented with dehydrated alfalfa in different concentrations makes a comparison between the treatments and the traditional control (wheat hay). In this case, the highest production in fresh weight was obtained with the PC-3Al treatment that corresponds to barley hay supplemented with 3 kg of dehydrated alfalfa, giving us a total of 13.32 kg (Figure 2); the second best production presented the treatment PC-2.5Al barley supplemented with 2.5 kg of dehydrated alfalfa, with 13.11 kg. The treatment that presented the lowest production was barley without supplementation (PC), with a total production of 10.22 kg, reporting significant differences with the multiple range Tukey test (p≤0.05).

Different letters indicate significant differences with the multiple range Tukey test (p≤0.05).

Figure 2 Total production of the CP-50 strain of P. ostreatus in barley haw substrate supplemented with dehydrated alfalfa.

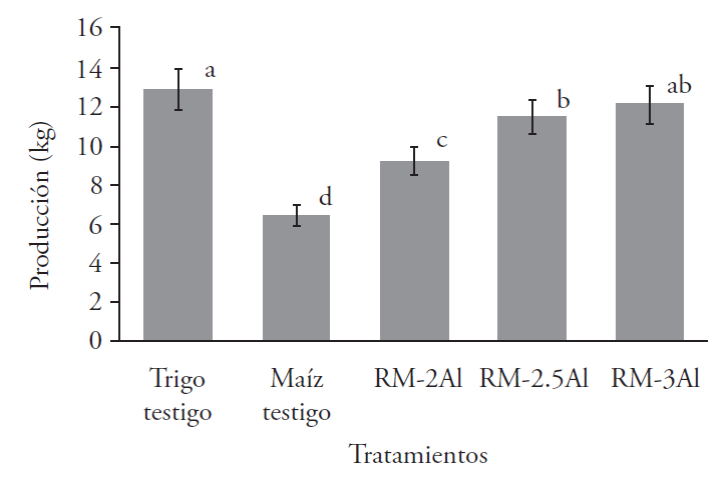

The total production obtained in the maize treatment supplemented with dehydrated alfalfa in different concentrations reported highly significant differences with the multiple range Tukey test (p≤0.05). The highest production in fresh weight was obtained with the RM-3Al treatment, which corresponds to maize stubble supplemented with 3okg of dehydrated alfalfa, obtaining a total production of 12.09 kg (Figure 3). The second best production was found with the “Wheat hay” control treatment, with 12.87 kg. The treatment that presented a lower production was maize stubble “RM”, with 6.43 kg. It should be mentioned that the treatments supplemented with dehydrated alfalfa outperformed maize stubble; in addition, it showed a similarity with wheat hay. A study performed by Flores (2012) mentions that the combination of yucca husk and wheat hay had a higher yield in comparison to the yucca husk alone. Similarly, Rajak et al. (2011) reported that with the combination of rice hay (substrate) and wild weeds from India (co-substrate), they obtained the highest yield in comparison to the wild weeds alone. This could be explained by the fact that the mixture of typical substrates contributes the nutrients necessary for the incubation and development of primordia and the formation of sporophores during colonization, while the co-substrates, whose decomposition is slower than that of substrates, provide the nutritional requirements necessary for the later phases of growth.

Different letters indicate significant differences with the multiple range Tukey test (p≤0.05).

Figure 3 Total production of the CP-50 strain of P. ostreatus in maize stubble supplemented with dehydrated alfalfa.

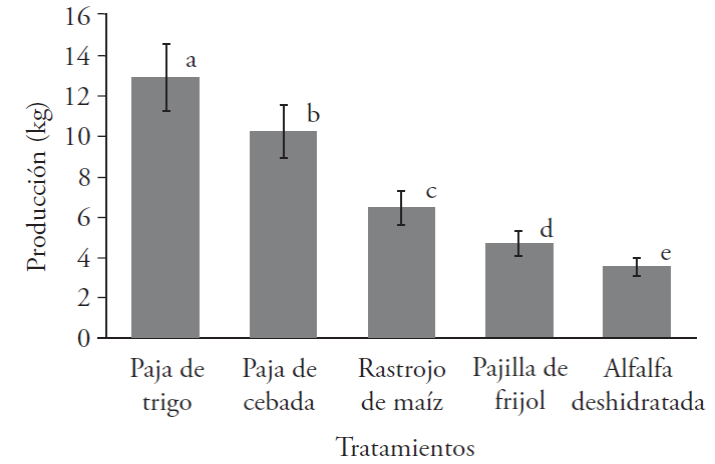

The total production obtained in the bean straw treatment supplemented with dehydrated alfalfa presented the highest production in fresh weight with the treatment (PT) that corresponds to wheat hay without supplementation, giving us a total of 12.87 kg (Figure 4); the second best production was presented by treatment PF-3Al, bean straw supplemented with three kilograms of dehydrated alfalfa with 8.41 kg. The treatment that presented the lowest production was the control bean straw (PF), with 4.68 kg, reporting significant differences (p≤0.05).

Quantification of BE, PR and BR for CP-50

The biological efficiency (BE) not only depends on the nutritional balance attained, but also on other environmental aspects, such as the capacity for water retention of the substrate, aeriation and relative moisture in several stages of cultivation (Mane et al., 2007). Mora and Martínez-Carrera (2007) reported biological efficiencies of 39 % to 162 % in wheat hay, with commercial strains of Pleurotus spp., results similar to this study. The PT-3Al treatment presented a BE of 179.40 %, similar to that found by Salmones et al. (1997) where they reported a BE of 75.6 to 68o% in 19 strains of Pleurotus spp., in a substrate of barley hay, lower values than those from this study (133.23 %). López et al. (2005) cite that maize stubble substrate presents a BE of 97 %, higher than those from the control group RM and RM-2Al in this research (64.30 and 91.85 %, respectively), although lower when being supplemented with dehydrated alfalfa at 2.5 and 3.0 kg, obtaining BE of 114.50 and 120.91 % (Table 3). The BE for bean straw residue without supplementing with dehydrated alfalfa is 46.84 %; when complementing this agricultural residue with dehydrated alfalfa, an increase of 60 % of its BE can be observed, higher than maize stubble (RM), but lower than the wheat hay (PT).

Table 3 Biological Efficiency (BE).

| Tratamientos | EB Testigos | EB % Suplementación de alfalfa deshidratada | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 | ||

| Paja de trigo | 128.70a | 154.08a | 157.27a | 179.40a |

| Paja de cebada | 102.20b | 127.66b | 131.11b | 133.23b |

| Rastrojo de maíz | 64.30c | 91.85c | 114.50c | 120.91c |

| Pajilla de frijol | 46.84d | 62.70d | 81.63d | 84.11d |

| Alfalfa deshidratada | 35.13e | |||

EB %: percentage of biological efficiency. *Means with different letters indicate significant differences with the Tukey test (P≤0.05).

The highest production rate (PR) was obtained in wheat hay supplemented with 3.0 kg of dehydrated alfalfa (1.48 %); the lowest PR, in the dehydrated alfalfa treatment (0.29 %). Mora (2004) reported a PR of 1.57 % in wheat hay; Gaitán-Hernández et al. (2009) reported a PR of 0.76 % in barley hay, similar results to those obtained in this study (Table 4).

Table 4 Production rate (PR).

| Tratamientos | TP % Testigos | TP (%) Suplementación de alfalfa deshidratada | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 | ||

| Paja de Trigo | 1.06a | 1.27a | 1.30a | 1.48a |

| Paja de Cebada | 0.84a | 1.06b | 1.08b | 1.10b |

| Rastrojo de Maíz | 0.53b | 0.76c | 0.95b | 1.00b |

| Pajilla de Frijol | 0.39c | 0.52d | 0.67c | 0.70c |

| lfa Deshidratada | 0.29c | |||

TP %: percentage of production rate. *Means with different letters indicate significant differences with the Tukey test (P≤0.05).

Likewise, the biodegradation rate (BR) presented by the P. ostreatus CP-50 strain showed that it is capable of converting up to 70 % of the substrate in food for human consumption, particularly in that of wheat hay supplemented at 3.0 kg of dehydrated alfalfa, which was the highest BR in comparison to the dehydrated alfalfa substrate, with 32 % and bean straw with 46 % (Table 5).

Table 5 Biodegradation rate (BR).

| Sustratos agrícolas | TB % Testigos | TB (%) Suplementación de alfalfa deshidratada | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 | ||

| Paja de trigo | 64a | 66a | 62a | 70a |

| Paja de cebada | 58b | 60a | 56b | 64a |

| Rastrojo de maíz | 52b | 54ba | 50b | 60ab |

| Pajilla de frijol | 46c | 48b | 68a | 52b |

| Alfalfa deshidratada | 32d | |||

TB %: percentage of biodegradation rate. *Means with different letters indicate significant differences with the Tukey test (P≤0.05).

The mean temperature inside the incubation area of the production units was 22.1 °C (minimum) and 28.16 °C (maximum) during the months of February to May, which was the period in which the production units remained inside the incubation area. Mora (2004) reported a weekly mean temperature of 20.3 °C to 27.7 °C, with a maximum of 27.2 and a minimum of 20.0 °C, and Gómez (2004) reported values that range from 23°C to 26.7 °C for the months of April to May, similar to those reported in this study. Regarding the fructification area, the mean temperature ranged between 18.4 °C (minimum) and 25.5 °C (maximum) during the months of June to September, where the last harvests were obtained. Gómez (2004) reported a mean temperature between 21 and 23.9 °C for the weeks of June to July; in addition, a relative humidity that ranged between 76.5 to 87.3 % for the months of May to June, similar results to those of this study, where the average relative humidity in the rustic module of production within the fructification area was 78.3 %. It should be mentioned that the temperatures of incubation and fructification that were present in the production module had higher values than those reported by Mora (2004) and Gómez (2004), due to the environmental conditions of location.

Proximal chemical analysis of substrates

The substrates used in this experiment presented a different chemical composition (Table 6). These differences make the productive capacity of the P. ostreatus CP-50 strain obtain higher yields in substrates rich in dry matter, such as the case of wheat hay, which presents a concentration of 90.10o%; raw protein, 3.34 %; ethereal extract, 0.22 %; ashes, 11.34 %; NDF, 85 %; and ADF, 51.14 %. Olavarría (2000) reports values of 1.7 % of ashes for barley hay, which are lower than those found in this study. Likewise, Beare et al. (2002) found 13.58 % of ashes for every 100 grams of dry substrate in maize stubble, values higher than those reported in this study. Yumi and Duchi (2007) report 2.5 % of protein in maize stubble, results that are lower in this study (4.9 % of protein without supplementing with dehydrated alfalfa and 8.93 % of raw protein when being supplemented with dehydrated alfalfa). Rivas (2005) mentions that alfalfa contains around 50 % of raw protein in the cell wall, as well as a balanced fiber composition, 8 % of pectin, 10 % of hemicellulose, 25 % of cellulose, and 7 % of lignin, which favors the development of sporocarps of the oyster mushrooms.

Table 6 Results of the Food Science Analysis of the substrates used in the production of P. ostreatus CP-50.

| % | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustratos | MS | PC | EE | Cenizas | FND | FAD | ||||||

| S/Al | C/Al | S/Al | C/Al | S/Al | C/Al | S/Al | C/Al | S/Al | C/Al | S/Al | C/Al | |

| PT | 90.10 | 98.45 | 3.34 | 7.12 | 0.22 | 0.67 | 11.04 | 14.02 | 85.0 | 92.04 | 51.14 | 58.67 |

| PC | 87.60 | 93,54 | 5.81 | 9.08 | 1.60 | 1.87 | 14.52 | 17.03 | 42.3 | 58.01 | 30.68 | 34.12 |

| RM | 93.82 | 98.35 | 4.90 | 8.93 | 1.23 | 1.64 | 6.83 | 9.05 | 72.45 | 89.02 | 46.75 | 49.31 |

| PF | 92.10 | 96.56 | 6.30 | 10.20 | 1.55 | 1.78 | 6.71 | 8.79 | 42.6 | 48.5 | 24.63 | 27.03 |

| AL | 21.90 | 12.51 | 2.13 | 9.08 | 34 | 27 | ||||||

PT: Wheat Hay, PC: Barley Hay, RM: Maize Stubble, PF: Bean Straw, AL: Dehydrated Alfalfa, *S/ AL: Without Alfalfa, C/Al: With Dehydrated Alfalfa (3 kg), M.S: Dry Matter, P.C: Raw Protein, E.E: Ethereal Extract, FND: Neutral Detergent Fiber and FAD: Acid Detergent Fiber.

Urbano and Dávila (2003) mention that the raw protein contribution is significant; alfalfa presents around 25 % of non-protein nitrogen, highly soluble and assimilable for saprophyte mushrooms, as shown by Danciang (1986), who studied the productivity of P. ostreatus in rice hay and sawdust, where they found that the first substrate produces a higher number of carpophores and of higher diameter than the ones developed in sawdust. The difference in the productivity of these substrates can be due to the differences in raw protein (15.10 %) and fat (0.35 %) for rice hay, versus 3.2 % of raw protein and 0.14 % of fat for the sawdust. In addition, Faner (2001) mentions that alfalfa is a good source of macrominerals (calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, potassium, chlorine), microminerals (zinc, copper, iron), vitamins (liposoluble, group B), and pigments.

Oyster mushrooms require substrates with a high amount of nutrients; in this sense, Amuneke et al. (2011) obtain 95 % of fructifications in substrates rich in protein. The increase in raw protein in the substrates indicates that P. ostreatus has a high capacity for synthesis, developing better (Sudiany et al., 2012).

In this research study, maize stubble presented a dry matter concentration of 93.82 %. When complemented with dehydrated alfalfa (3.0 kg), an increase in BE, PR and BR was found, since its content of dry matter increased to 98.35 %; raw protein, from 4.90 to 8.93 %; ethereal extract, 1.23 to 1.64 %; ashes, 6.83 to 9.05 %; NDF, 72.45 to 89.02 %; and ADF, 46.75 to 49.31 %, turning it from a low-yield substrate to a high-yield substrate in the production of oyster mushrooms. In addition, its availability in rural zones of the municipality of Tetela de Ocampo, Puebla, favors its production.

It should be clarified that the figures presented before are average values of the substrates from the municipality of Tetela de Ocampo, Puebla, but there is broad variation for the proximal chemical analysis; for example, the protein in barley fiber varied from 3.9 to 8.7 %; in wheat, from 2.4 to 5.8 %; in maize stubble, from 2.0 to 7.1%; and in bean straw, from 6.0 to 7.9 %. The variation comes primarily from the type of plant, although other factors are also important such as the variety, the degree of maturity, management, soil fertility, sowing season, frost events, etc., which influence the general development of plants and, consequently, their nutritional constitution (Romero-Arenas et al., 2010).

Conclusions

The production of the P. ostreatus CP-50 strain lasted 121 days, where the highest production in fresh weight was obtained with the PT-3Al treatment, which corresponds to wheat hay supplemented with 3 kg of dehydrated alfalfa, with 17.94 kg. The second was shown by PT-2.5Al, which corresponds to wheat hay supplemented with 2.5 kg of dehydrated alfalfa. The third was the treatment PC-2.5Al, which corresponds to barley hay supplemented with 2.5 kg of dehydrated alfalfa, while the lowest production was found in the “Dehydrated alfalfa” treatment, with a weight of 3.51 kg.

The use of dehydrated alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) as supplement in conventional substrates from Tetela de Ocampo, Puebla, increased the biological efficiency BE and biodegradation rate BR of the CP-50 strain of P. ostreatus. In addition, it obtained an excellent development in the maize stubble substrate supplemented with 2.5 and 3.0 kg of dehydrated alfalfa, obtaining a BE of up to 120.91 %. Thus, locally-produced residues can be used for oyster mushroom production.

Lastly, the controlled conditions of facilities where the incubation and harvest process were carried out are important for the crop, conserving a room temperature of 26±2 °C, moisture between 70 and 80 % for the good development of fructifying bodies and air extraction for 1 h, every 8 h; these considerations in the production of oyster mushrooms influence directly the development and quality of sporocarps.

Literatura Citada

A.O.A.C. (Association of Official Analytical Chemists) 1980. Official methods of analysis of association of official agricultural chemist. 13th ed. Washington, D. C. 978 p. [ Links ]

Adebayo, E. A., D. Martinez-Carrera. 2015. Oyster mushroom (Pleurotus) are useful for utilizing lignocel- lulosic biomass. Review African Journal of Biotechnology. 14(1): 52-67. [ Links ]

Aguirre, H. 2000. Aislamiento y caracterización de cepas de Pleurotus spp. nativas de Morelos y su cultivo en cuatro substratos. Tesis de Licenciatura, UAEM. [ Links ]

Akinyele, B., J. Fakoy., and C. Adetuyi. 2012. Anti-Growth Factors Associated with Pleurotus ostreatus in a Submerged Liquid Fermentation. Malaysian Journal of Microbiology. 8(3): 135-140. [ Links ]

Amuneke, E. H., K.S. Dike., and J. N. Ogbulie. 2011. Cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus: An edible mushroom from agro base waste products. Microbiol. Biotech. Res. 1(3):1-14. [ Links ]

Andrino, A., A. Morte., y M. Honrubia. 2011. Caracterización y cultivo de tres cepas de Pleurotus eryngii (Fries) Quélet sobre sustratos basados en residuos agroalimentarios. Anales de Biología. 33(1): 53-66. [ Links ]

Beare, M., P. Wilson., P. Fraser., and R. Butler. 2002. Management effects on barley straw decomposition, nitrogen release, and crop production. Soil Science Society of American Journal. 66(1): 848-856. [ Links ]

Buswell, A. J., J. Cai., and S. T. Chang. 1993. Fungal and substrate associated factors affecting the ability of individual mushroom species to utilize different lignocellulosic growth substrates. In: S.T. Chang, J.A. Buswell, S.W. Chiu (eds). Mushroom biology and mushroom products. The Chinese University Press, Hong Kong. pp: 141-150. [ Links ]

Cedano, M., M. Martínez., C. Soto-Velazco., and L. Guzmán-Dávalos. 1993. Pleurotus ostreatoroseus (Basidiomycotina, Agaricales) in México and its growth in agroindustrial wastes. Cryp. Bot. 3: 397-302. [ Links ]

Chang, S.T., and S. P. Wasser. 2012. The role of culinary medicinal mushrooms on human welfare with a pyramid model for human health. Int J Med Mushrooms. 1: 95-134. [ Links ]

Cunha, Z. D., and G. A. Pardo. 2017. Edible and Medicinal Mushrooms: Technology and Applications. Ed. John Wiley & Sons Ltd. U.S.A. 592 p. [ Links ]

Danciang, C. 1986. Culture of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus Florida) on five farms wastes at different levels of ammonium sulfate. Scientific Journal. 6(1): 64. [ Links ]

Enciclopedia de los municipios de Puebla 2013. Sistema estatal y municipal de base de datos. (Consulta: Julio 2016). http://sc.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/cobdem/contenido.jsp?rf=false&solicitud= [ Links ]

Fanadzo, M., D. T. Zireva., E. Dube, and A. B. Mashingaidze. 2010. Evaluation of various substrates and supplements for biological efficiency of Pleurotus sajor-caju and Pleurotus ostreatus. African Journal of Biotechnology. 19: 2756-2761. [ Links ]

Faner, C. 2001. Utilización de la pastura en alimentación porcina. Memoria de Fericedo. EEA INTA. México. pp: 2-7. [ Links ]

Flores, R. G. 2012. Aprovechamiento del bagazo residual de Yucca spp. como sustrato para la producción de Pleurotus spp. Tesis de Maestría. Unidad Profesional Interdisciplinaria de Biotecnología. Instituto Politécnico Nacional. México. 111 p. [ Links ]

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). 2014. Available online: Available online: http://faostat.fao.org/site/567/DesktopDefault.aspx?PageID=567#ancor (acesado el 10 de abril de 2016). [ Links ]

Franco, W. J. 1990. Métodos de análisis utilizados para la evaluación de proteína. CINVESTAV-IPN. México, D.F. [ Links ]

Gaitán-Hernández, R., P. Salmones., P. Dulce., R. Merlo., y G. Mata. 2009. Evaluación de la eficiencia biológica de cepas de Pleurotus pulmonarius en paja de cebada fermentada. Revista mexicana de micología. 30: 63-71. [ Links ]

Garzón, G., J. P. Leonardo., y C. Andrade. 2008. Producción de Pleurotus ostreatus sobre residuos sólidos lignocelulósicos de diferente procedencia. NOVA. 6(10): 101-236. [ Links ]

Gómez, A. 2004. Evaluación de la eficiencia biológica de dos cepas comerciales de Pleurotus ostreatus con relación al tamaño de bolsa sobre paja de trigo. Morelos, México. Tesis de Licenciatura, UAEM. [ Links ]

Kumari, D., V. Achal. 2008. Effect of different substrates on the production and nonenzymatic antioxidant activity of Pleurotus ostreatus (Oyster mushroom). Life Sciences Journal. 5: 73-76. [ Links ]

López, C., E. H. Ancona., y P. S. Medina. 2005. Cultivo de Pleurotus djamor en laboratorio y en una casa rural tropical. Revista mexicana de micología . 21: 93-97. [ Links ]

López, R., C. Hernández., C. R. Suárez., y F. C. Borrero. 2008. Evaluación del crecimiento y producción de Pleurotus ostreatus sobre diferentes residuos agroindustriales. Universitas Scientiarum. 13(2): 128-137. [ Links ]

Mane, V. P., S. S. Patil., A. A. Syed., and M. V. Baig. 2007. Bioconversion of low quality lignocellulosic agricultural waste into edible protein by Pleurotus sajor-caju (Fr.) Singer. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 8(10): 745-51. [ Links ]

Martínez-Carrera, D., A. Larqué-Saavedra., A. Tovar-Palacio., N. Torres., M. E. Meneses., M. Sobal-Cruz., P. Morales-Almora., M. Bonilla-Quintero., U. H. Escudero., I. Tello-Salgado., T. Bernabé-González., W. Martínez-Sánchez., e Y. Mayett. 2016. Contribución de los hongos comestibles funcionales y medicinales a la construcción de un paradigma sobre la producción, la dieta, la salud y la cultura en el sistema agroalimentario de México. In: Martínez-Carrera D., J. Ramírez Juárez (eds); Ciencia, tecnología e innovación en el sistema agroalimentario de México. Editorial del Colegio de Postgraduados-AMC-CONACYT-UPAEP-IMINAP, San Luis Huexotla, Texcoco, México, pp: 581-640. [ Links ]

Martínez-Carrera, D. , P. Morales., M. Sobal., M. Bonilla., W. Martínez., eY. Mayett . 2012. Los hongos comestibles, funcionales y medicinales: su contribución al desarrollo de las cadenas agroalimentarias y la seguridad alimentaria en México. In: Memorias Reunión General de la Academia Mexicana de Ciencias: Ciencia y Humanismo (Agrociencias). Academia Mexicana de Ciencias, México, D.F. pp: 449-474. [ Links ]

Martínez-Carrera, D. , P. Morales ., M. Sobal , M. Bonilla ., yW. Martínez . 2007. México ante la globalización en el siglo XXI: el sistema de producción consumo de los hongos comestibles. Capítulo 6.1, 20 p. [ Links ]

Medel, R., T. Espinosa., A. Sánchez., O. Romero-Arenas., y L. Reyes. 2011. Diversidad de Hongos Capítulo 4. Biodiversidad de Puebla Estudio de Estado. Edición: BUAP, CONABIO y Gobierno del estado de Puebla. ISBN: 978-607-7607-54-0. Puebla, México. 409 p. [ Links ]

Mora, V. 2004. Estudio comparativo de diferentes cepas comerciales que se cultivan en México de Pleurotus spp. Tesis de Maestría. UNAM. [ Links ]

Mora, V., y D. Martínez-Carrera. 2007. Investigaciones básicas, aplicadas y socioeconómicas sobre el cultivo de setas (Pleurotus) en México. Capítulo 1.1. In: El Cultivo de Setas Pleurotus spp. en México. J.E. Sánchez., D. Martínez-Carrera., G. Mata ., H. Leal (eds). ECOSUR-CONACYT. ISBN 978-970-9712-40-7.b. México, D.F. 230 p. [ Links ]

Rajak, S., S. C. Mahapatra., and M. Basu. 2011. Yield, Fruit Body Diameter and Cropping Duration of Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus sajor caju) Grown on Different Grasses and Paddy Straw as Substrates. Eur. J. Med. Plants. 1: 10-17. [ Links ]

Reyes, G.R., A.E., Abella, F., EguchI, T., Iijima, M., Higaki, and T.H., Quimio. 2004. Growing paddy straw mushroom. In: Mushroom grower´s handbook; Oyster mushroom cultivation. Mushroom World. Corea. pp: 262-269. [ Links ]

Rivas, J. M. A., C. C. López., G. A. Hernández., y P. J. Pérez. 2005. Efecto de tres regímenes de cosecha en el comportamiento productivo de cinco variedades comerciales de alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Téc Pecu Méx. 43(1): 79-92. [ Links ]

Romero-Arenas, O., M. Huerta., M. A. Damián., A. Macías., J. A. Rivera., F. C. Parraguirre., y J. Huerta. 2010. Evaluación de la capacidad productiva de Pleurotus ostreatus con el uso de hoja de plátano (Musa paradisiaca L., cv. Roatan) deshidratada, en relación con otros sustratos agrícolas. Agronomía Costarricense. 34(1): 53-63. [ Links ]

Romero-Arenas, O. , M. A. Martínez., M. A. Damián ., B. Ramírez., y J. López-Olguín. 2015. Producción de hongo Shiitake (Lentinula edodes Pegler) en bloques sintéticos utilizando residuos agroforestales. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. 6(6): 1229-1238. [ Links ]

Royse, D. J., J. Baars., and Q. Tan. 2016. Current overview of mushroom production in the world. In: Zied DC, editor. Edible and medicinal mushrooms: technology and applications. New York, Wiley. 462 p. [ Links ]

SAGARPA-SIAP (Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación-Servicio de Información Alimentaria y Pesquera). 2015. Situación actual y perspectivas de alfalfa verde en México 2010-2015. Consultado el 01/09/2017 en Consultado el 01/09/2017 en http://infosiap.siap.gob.mx/aagricola_siap_gb/icultivo/index.jsp . [ Links ]

Salmones, D., H. R. Gaytán., R. Pérez., y G. Guzmán. 1997. Estudios sobre el género Pleurotus VIII, Interacción entre crecimiento micelial y productividad. Rev. Iberoam Micol. 14: 173-176. [ Links ]

Sobal, M., D. Martínez-Carrera ., P. Morales ., and S. Roussos. 2007. Classical characterization of mushroom genetic resources from temperate and tropical regions of Mexico. Micología Aplicada International. 19(1): 15-23. [ Links ]

Received: June 01, 2014; Accepted: August 01, 2017

text in

text in