Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Agricultura, sociedad y desarrollo

Print version ISSN 1870-5472

agric. soc. desarro vol.14 n.4 Texcoco Oct./Dec. 2017

Articles

Impact of payment for hydrological environmental services in forests from three ejidos in Texcoco, México

1 Campus Montecillo, Colegio de Postgraduados. Km.36.5 Carretera México-Texcoco. Montecillo, Texcoco, Estado de México. 56230. México. (evaltier@colpos.mx)

The objective of this study is to analyze the situation of ejido forest properties after having participated in the Program for Hydrological Environmental Services (PSAH) of the National Forest Commission (CONAFOR) from 2005 to 2010. At the beginning the three forest properties were classified as “Resting”; that is, that they were not used for timber extraction. During this period, the condition of the forest in the three properties participating in the PSAH improved, due to the soil conservation and reforestation works, and because during the five years there was no timber extraction. In 2011, the ejidos decided to restart timber exploitation in two of the properties benefitted when the payment for environmental services ended. However, the third property was preserved as a conservation area. This means that the payment made by the CONAFOR through the PSAH does not guarantee the conservation of forests or the provision of environmental services in the long term.

Key words: forest conservation; forest properties; timber extraction; reforestation; conservation works

El objetivo del estudio es analizar la situación de los predios forestales ejidales después de haber participado en el Programa de Servicios Ambientales Hidrológicos (PSAH) de la Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR) de 2005 a 2010. Al inicio los tres predios forestales estaban clasificados como “En reposo”; esto es, que no se les hacía aprovechamiento de la madera. Durante este período, la condición del bosque de los tres predios participantes en el PSAH mejoraron por las obras de conservación de suelos y reforestación, y porque durante los cinco años no se hicieron aprovechamientos maderables. En 2011, los ejidos decidieron reiniciar el aprovechamiento maderable en dos de los predios beneficiados cuando finalizó el pago por servicios ambientales. Sin embargo, el tercer predio fue preservado como área de conservación. Esto significa que el pago hecho por la CONAFOR a través del PSAH no garantiza la conservación de los bosques ni la provisión de servicios ambientales en el largo plazo.

Palabras clave: conservación de bosques; predios forestales; aprovechamientos maderables; reforestación; obras de conservación

Introduction

Fresh water in the world constitutes an increasingly scarce resource, threatened and at risk of being contaminated. Underground water is a source of fresh water of high quality and represents a third of all the fresh water deposits in the world. More than 40 % of this water is used for agriculture, followed by domestic use (more than 30o%), and industry use (more than 20 %) (Taylor et al., 2013).

Underground water performs a fundamental role in the maintenance of ecosystems. Water is intercepted by forest vegetation, the quality and quantity of water depends on different factors, such as age of the vegetation, species, phytosanitary state of the forest, and forestry activities carried out with the vegetation; therefore, the loss of forest surface affects the quantity and quality of water (González-Guillén et al., 2006).

The population increase, the strong competition over spaces for agriculture and the growing demand for timber have unchained a vertiginous process of deforestation that continues to affect about 13 million hectares per year (Montes and Sala, 2007). From 1990 to 2000 an average of 354 thousand hectares was deforested annually, and from 2005 to 2010 the deforestation rate was reduced to 155 thousand hectares annually (CONAFOR, 2011).

Deforestation is one of the main factors that accentuate climate change, which can gravely impact the fresh water reload in the subsoil. Some studies (Allan and Soden, 2008; Bates et al., 2008) point out that the future effects of climate change on the fresh water reload can be quite serious because the drought periods may be longer, while the rainfall less frequent, but of higher intensity (causing flooding and less water infiltration to the subsoil).

One of the measures implemented since the 1990s for the conservation of forests and to maintain the water supply destined to human consumption and to productive activities was payment for hydrological environmental services to the owners of the forests and rainforests. Porras et al. (2008) performed a study that included 287 cases of payment plans for hydrological environmental services in developing countries.

Programs of payment for environmental services promoted by national or local governments seek to be temporary payment mechanisms that the State makes to owners of the forests and rainforests while a market for environmental services is formed where water consumers pay some amount of money to the forest owners for their conservation, allowing to maintain underground water infiltration and runoffs toward superficial channels.

López-Morales (2012) points out that, according to official statistics from the National Water Commission (Comisión Nacional del Agua) in 2011, up to 2.3 times the volume of renewable flow (superficial and underground) is used in the central zone of the country, which generates the highest regional water stress indicators in the country. In particular, the annual extraction of underground water, which provides around 70 % of the water used in the region, is equivalent to about two times the reload volume of the aquifer system, generating a group of problems that includes sinking, decrease of water table levels, loss of quality, or increases in the cost of extraction.

Therefore, and with the objective of protecting the supply capacity of hydrological environmental services, in 2003 the Mexican Government implemented the Program for Hydrological Environmental Services (Programa de Servicios Ambientales Hidrológicos, PSAH) (SEMARNAT, 2003). Some of these environmental services are: maintenance of the reload capacity of aquifer tables and maintenance of the quality of water, conservation of water sources, among others (Ruiz-Pérez et al., 2007).

The main objective of the PSAH is to guarantee the permanence and conservation of forest ecosystems, through economic compensation that CONAFOR grants the owners and holders of forests and rainforests who decide to conserve their tree-covered forest areas to provide hydrological services to society (SEMARNAT, 2003).

The assumption that CONAFOR starts from is that the vegetation coverage in México cannot only be conserved, but rather it can be increased by paying the land owners for the environmental services (positive externality) they provide, whether by using sustainable production systems, reforesting and/or conserving forests.

Based on the Soil and Vegetation Use Charts elaborated by INEGI, the analysis by CONAFOR shows that the rate of net forest loss has decreased in half between 2005 and 2010 in México (CONAFOR, 2011).

However, one of the main problems that the PSAH faces is the lack of alternatives for the forest owners, once the program has reached its end. There are very few cases where local schemes for payment of environmental services have been generated or where access to voluntary payment plans for environmental services has been facilitated. This indicates that, after the five years of backing from the program, there is no guarantee that producers will continue to conserve the properties supported, and that the conditions present before participating in the program will not return, or else, that they will begin performing timber extraction.

The PSAH must mark the difference in the conservation of the properties benefitted and in the provision of hydrological environmental services; on the contrary, this program will be functioning only as another program for temporary subsidy and will not guarantee forest conservation once the producer ceases to receive the financial support.

The main objective of this study is to understand what happened to ejido forest properties after having participated in the Program for Hydrological Environmental Services (PSAH) of the National Forest Commission (Comisión Nacional Forestal, CONAFOR) from 2005 to 2010. This study’s hypothesis is that backing from the PSAH improves the conditions of forests, but does not guarantee that the forests benefitted with the subsidies will maintain the provision of environmental services in the medium and long term, once the flow of subsidies ends.

Methodology

Study area

The research was carried out in three ejidos of the municipality of Texcoco, Estado de México: Ejido San Miguel Tlaixpan, Ejido San Pablo Ixayoc and Ejido Tequexquinahuac. The three ejidos are located in the forest area known as “mountainous zone”, which is the highest part of the municipality and where most of the forest ejidos and communities are located.

This municipality is located in the eastern foothills of the endorheic basin called “Valle de México”, at a distance of 25 km from Mexico City, between geographic coordinates: Longitude 98° 39’ 28” W and 99° 01’ 45” W; Minimum Latitude: 19° 23’ 40” N and 19° 33’ 41”. The territorial extension is 418.69 square kilometers and located in eastern Estado de México, at an approximate distance of 25 kilometers from Mexico City1.

This study was performed in the municipality of Texcoco which has, according to the INEGI (2010) census, a population of 235 151 people; however, it shares the aquifer with Chicoloapan, Chimalhuacan and Nezahualcoyotl, which are among the municipalities with highest population number and density in the country. This situation makes the aquifer on which Texcoco is settled one of the most overexploited in the whole county. According to the National Water Commission (CONAGUA), Texcoco is located in the Water Extraction Zone 9-01 Valle de México, whose hydrological condition is of extreme overexploitation, which is why it has been declared as a closed zone for the opening of new wells. Escobar and Palacios (2012) calculated the rate of aquifer overexploitation in -67.61 hm3 year-1, which translates into an average annual reduction of the water table of 1.20 meters during the period 1969-2009.

For this reason, this aquifer was selected by CONAFOR and PROBOSQUE as a zone to support actions for the recharge of aquifers through environmental services.

Case study method

The study was performed in 2012, based on the case study method. This has a qualitative and descriptive character, primarily, even when both qualitative (flexible structured interviews, observation and others) and quantitative (archives, field measurements, and others) information is gathered. The results from this method cannot be inferred for a larger population, but they allow an examination and in-depth scrutiny from the gathering of a large amount of detailed data, allowing a complete image of a social phenomenon (Salkind, 1999).

Rodríguez (1996) mentions that a study of multiple cases presents more convincing evidences and, therefore, the study is more robust; because of this, three cases were selected.

Sampling

The selection of the three ejidos was made based on three common characteristics: 1) they are located in the same forest zone of the municipality of Texcoco; 2) they were benefitted by the Federal Program for Hydrological Environmental Services during the 2005-2010 period; and 3) the five years of backing from this program had already concluded.

Non-probabilistic directed sampling was carried out because the PSAH beneficiaries are the ejidos and not the individual ejidatarios, which is why most of them did not understand the process of negotiating the backing and many didn’t even receive payments for their workdays because they did not work in the tasks carried out on the properties benefitted. Therefore, the greatest part of the information came from key informants who functioned as ejido representatives in the management of PSAH supports and were the ones who organized the conservation works in the properties benefitted by the program.

A quota sample was taken of five ejidatarios per ejido (15 in total) who had participated in the construction of conservation works and tasks in the properties benefitted. The ejidatarios were asked only a few questions to corroborate aspects that they knew about, such as, for example, accountability of the PSAH resources, or else, about information that would interest them, such as payment of workdays that they received for their work in the conservation tasks. Therefore, this sample of ejidatarios cannot be considered representative and only had the function of detecting inconsistencies, imprecisions, or explanations given by the key informant. In the end, no significant discrepancies were found between the leaders and the ejidatarios.

Lastly, an interview was performed with the Forest Technical Services Provider (Prestador de Servicios Técnicos Forestales, PSTF) from each ejido. A questionnaire was designed with a much more technical approach, but also repeating some points to verify the information obtained with the key informants and ejidatarios chosen randomly.

Research instruments

Structured interviews: Three questionnaires were designed that served to gather information through direct interviews with the social actors: key informants, ejidatarios and technical advisory staff.

Field visits: Field visits were carried out in the three ejidos, visiting the forest properties that participated in the PSAH program with the aim of understanding the different conservation practices and tasks that were performed in the forest during the period of backing, as well as understanding their current state once the support from the program ended. In the three cases a commission was designated, integrated by two or more people from each ejido who knew the place perfectly well and who had been fully involved in the PSAH activities.

Participant observation: It is a research and learning method through which the researcher is exposed and becomes involved in the day-to-day life or routine activities of the participants (Kawulich, 2005). The information was obtained during several visits to the ejidos where activities of the ejidatarios were observed, performing activities related to the forest.

Results

Condition of the properties benefitted, before participating in the PSAH program

The predominant forest species in the three ejidos was Abies religiosa (sacred fir), occupying more than 60 % of the total surface of each one of the properties. This was due to the altitudinal characteristics of these properties (above 2500 masl). The second predominant species was pine (Pinus hartwegii, Pinus pseudostrobus, Pinus montezumae (ocote) and in a lower percentage, oak (Quercus spp.).

At the beginning of their participation in the program, the three properties were contemplated within the forest management program of each ejido, except under status of “in recovery or rest”. This means that during the five years of backing they could not be exploited to allow the forest tree cover to become stronger. In 2005 the properties in the ejidos of Tequexquinahuac and San Pablo Ixayoc were waiting to be exploited, and in the case of the ejido of San Miguel Tlaixpan the property had just been exploited.

According to the information obtained, one of the main reasons to participate in the PSAH was not only to continue caring for and conserving the forest, but also because the participating property was resting at that moment.

In the three cases the surface backed was 200 hectares located in a single property or polygon. This coincidence is because in 2005 the area in recovery or rest did not have to exceed 200 hectares per beneficiary. Therefore, each ejido could not aspire to participate with a larger surface.

In the three cases the participating properties were not the areas with highest risk of deforestation, nor were they abandoned areas, but rather they were included within the ejido’s Forest Management Program. Even in the ejido of San Miguel Tlaixpan, the participating property was the best conserved zone of the forest.

Payments for hydrological environmental services

The main mechanism for backing from the PSAH toward the ejidos was the transference of economic resources in exchange of two principal conditions: 1) not to perform forest extraction in the properties benefitted; and 2) to carry out conservation works and tasks to improve the ecological conditions of the properties to maintain the plant coverage.

In 2005, the PSAH paid a fee of $300.00 ha-1, which meant an amount of $60 000.00 annually for the 200 ha in each property benefitted. The money had to be destined to paying for workdays, services and materials necessary to perform conservation works and activities. When asking the ejidatarios what they invested the resources in, the ejido of Tequexquinahuac and San Pablo Ixayoc pointed out that they were destined entirely to the forest conservation actions and in the ejido of San Miguel Tlaixpan, 60 % was destined to conservation actions and 40 % to building the ejido hall.

None of the ejidos destined the money to distribute to ejidatarios, which is why the only form of economic benefit was payment for workdays to carry out conservation works. In the interviews they key informants and the ejidatarios agreed that the fee paid by the PSAH is too low and that it doesn’t even cover the costs of giving good maintenance to the forest. The majority agreed that the fee should be at least $1500.00, in addition to paying for the whole surface of the ejido and not only for 200 ha. Even so, the interview respondents appreciated the backing received from the PSAH because they considered that the conditions of the forest improved.

According to Porras et al. (2008), the payment from programs for environmental services promoted by the national or local governments seek to be temporary payment mechanisms that the State makes to owners of forests and rainforests, while a market for environmental services is formed where water consumers pay a certain amount of money to the forest owners for their conservation that allows maintaining the infiltration of underground water and runoffs toward superficial channels.

Key informants pointed out that CONAFOR never suggested the possibility of creating a permanent market mechanism where consumers of water extracted from the aquifer would pay the ejidatarios a certain amount for payment of hydrological environmental services provided by their forests. This meant that at the end of the five years of backing granted by the PSAH the ejidos ceased to obtain income for environmental services.

Conservation works, of soil and water, carried out during the backing period

In 2005 the operation rules of the PSAH did not contemplate the implementation of the Better Management Practices Program (Programa de Mejores Prácticas de Manejo, PMPM). Within the rights and obligations of the PSAH beneficiaries, it was only considered to “maintain as minimum vigilance of the property”, with the aim of ensuring the conservation of the same forest cover that the property had at the beginning of the backing.

Backing of the PSAH to the three ejidos began in 2005, which is why none of them had the commitment or obligation of performing activities of conservation or restoration in their properties. However, in the three cases several activities were carried out to improve the conditions of the forest.

Some of the works performed were: reforestations, opening ditch trenches, dams with branches, andirons and arranged stones, opening firebreak trails, arrangement of dead plant material, placing signs, pruning and chaponeo, among others.

Reforestations: Reforestation was an activity carried out in the three ejidos; although there was a variation in the number of hectares reforested, this difference was not significant. The ejido with smallest surface reforested was San Pablo Ixayoc (15 ha) and the largest was San Miguel Tlaixpan (30 ha).

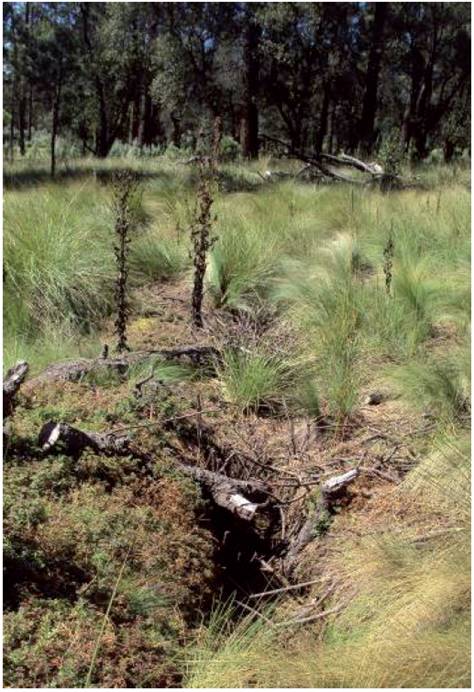

Blind tubs or ditch trenches: They were made in the ejidos of San Miguel Tlaixpan and Tequexquinahuac. In the first these works covered a surface of two hectares. The size of the ditches was two meters long by 0.5 m deep, and 0.4 wide. In Tequexquinahuac a total surface of three hectares was covered, with presence of ditches of two different sizes, two and five meters long (Figure 1).

Branch dams: They were built only in the ejidos of Tequexquinahuac and San Pablo Ixayoc, with the objective of retaining sediments, as well as reducing the speed of runoff. In total, four works of this type were identified in the ejido of San Pablo Ixayoc and three in Tequexquinahuac (Figure 2).

Andiron dams: The ejidos of Tequexquinahuac and San Pablo Ixayoc were the only ones that carried out this type of works for soil conservation. In Tequexquinahuac, three dams of this type were found, and five in San Pablo Ixayoc.

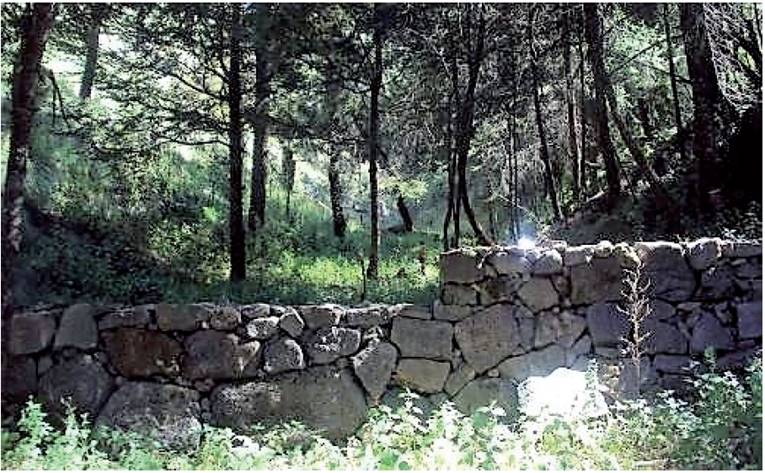

Arranged stone dams: This type of works was only performed in the ejido of Tequexquinahuac, building in total three dams (Figure 3).

Repair and maintenance of paths: The three ejidos invested resources in this type of works. They joined efforts and resources to repair, together, part of the main access road to the forest, since the benefit was collective. However, San Pablo Ixayoc invested more resources in the repair of secondary roads (Figure 4).

Vigilance: The vigilance activities were covered totally by the three ejidos, without the support of the PSAH, although the ejido of San Pablo Ixayoc is the one that stood out most in this activity.

Firefighting brigades: None of the three ejidos has a permanent firefighting brigade; however, both Tequexquinahuac and San Pablo Ixayoc are very well organized to combat the fires when they happen. In its turn, San Miguel Tlaixpan does not have a defined strategy where each brigade member executes a function to combat this type of disasters, which is why they have asked for support from neighboring ejidos when a fire has taken place.

Opening and maintaining firebreak trails: The three ejidos already have a Forest Management Program, including the properties supported. This means that the firebreak trails had been traced prior to the PSAH and they only gave them maintenance. Only the ejido of San Miguel Tlaixpan opened a new trail (50 meters long) (Figure 5).

Placing signs: Although it was not mandatory, the three ejidos placed more than two signs in each property supported (5 to 20 signs) (Figure 6).

Condition of the forest properties once backing from the PSAH concluded

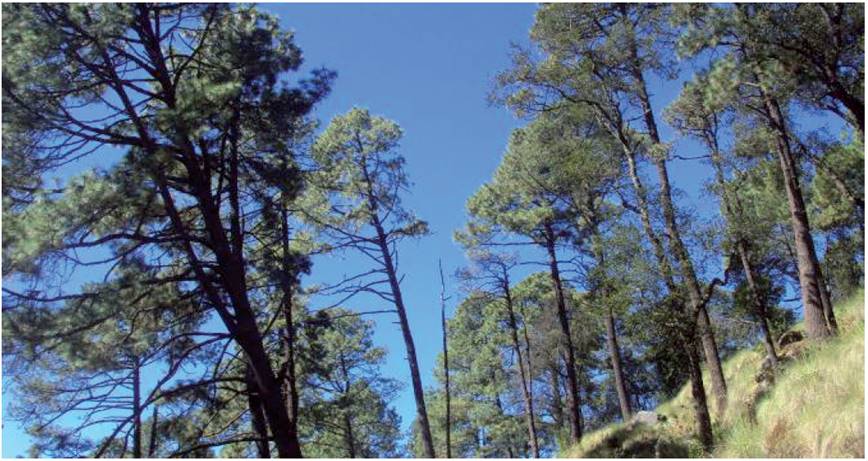

In the interviews, the ejidatarios and the key informants manifested that the properties benefitted by the PSAH are in better conditions today than at the beginning of the program backing because works to improve the forest were carried out with resources from the program. In the field visits it was observed that the forests in the three ejido properties have a vigorous, healthy and pleasant appearance as a result of the good care and management that ejidatarios have performed. Therefore, the properties fulfill adequately the provision of hydrological environmental services (Figure 7).

All the interview respondents agreed that the forest properties supported by the PSAH are in better conditions than before receiving the backing and they pointed to three reasons: 1) in the properties benefitted no timber extraction was done for five years; 2) the ejidos fulfilled the commitments acquired through operation rules of the PSAH because they carried out conservation works and activities to improve the forest conditions (reforestations, works for soil and water conservation, prevention of fires, among others) with the PSAH resources; and 3) no serious disasters took place (such as the presence of fires, pests or diseases), or problems with clandestine felling in the three periods supported.

Two years after having concluded with the payments for environmental services from CONAFOR to the three ejidos, the ejidatarios continue to perform some improvement activities. For example, it was observed in the field that in Tequexquinahuac chaponeos and pruning were performed; in San Miguel Tlaixpan, reforestations and maintenance of firebreak trails; and in San Pablo Ixayoc constant vigilance is still being performed.

After concluding their participation in the PSAH, currently only one of the ejidos continues to receive backing from CONAFOR and the other two participate in the Payment for Hydrological Environmental Services of the Estado de México government. However, the three are participating with properties different from the ones backed by the PSAH from 2005 to 2010. This indicates that they have been able to take advantage of the backing available in different levels of government (federal and state), which is motivated because the payments for environmental services that the PSAH grants were very scarce.

The properties from the three forest ejidos that participated in the PSAH (2005-2010) currently have the following use:

The property in the ejido of Tequexquinahuac is being exploited under the Forest Management Program because its “resting” time has concluded, as well as its participation in the program. Today’s interest in the ejido is to carry out timber extraction.

The property in the ejido of San Miguel Tlaixpan was declared “reserve area”, with the aim of conserving it and not making timber extractions. The decision of the ejido was based on the fact that this property is located at a distance far from the ejido nucleus, which is why it has always been one of the areas of the forest best conserved and is found on the perimeter of the Izta-Popo National Park, which is a Natural Protected Area. The property is currently in closed season and is being watched by the ejidatarios, although extraction of moss and lama has been authorized.

Lastly, the property in the ejido of San Pablo Ixayoc is waiting to be exploited, once the new Management Plan in the ejido is approved, because the last one’s validity ended in 2010.

Discussion

The public policy line of the program for payment of environmental services was to find, during the first stage, the federal resources where it can make a greater difference. That is, in forest areas that do not generate income for their owners and which for that reason are considered to be in greater danger of deforestation from change of land use (González-Guillén et al., 2006). In the ejidos studied this premise was not fulfilled since in the three cases the participating properties were not the areas at higher risk of deforestation, nor were they abandoned areas.

The PSAN stems from the assumption that non-intervention with the aim of timber extraction in forest areas is always a sufficient strategy to ensure their conservation. Under this premise the operation rules of the PSAH do not consider backing for properties with timber extraction, but rather only consider those that are within a management program that are “areas in recovery or rest”. This approach is called “Passive Conservation”, because it is considered that the forest will be conserved without touching it or, in the best case scenario, by performing some conservation works and tasks.

The national forest policy does not support the idea that “a forest or property that is being exploited is capable of providing the same environmental benefits that one that is not touched”. That is, “Active Conservation” or good management is not acceptable for the CONAFOR’s PSAH.

Taylor (2013) indicates that deforestation is a factor that promotes climate change. The impact of these effects on the aquifer reload is not entirely understood; however, prior evidence (Tague and Grant, 2009; Sultana and Coulibaly, 2011) indicate that changes in the ice thawing regime tend to reduce the duration and magnitude of the reload. A considerable decrease in the water table levels in Texcoco can result in insufficient water to satisfy the domestic and agricultural requirements, and to maintain the basic ecological functions in a medium term.

A well-managed forest should not belittle the quality and quantity of provision of water and other environmental services. In a study carried out by Návar-Cháidez (2011) it was found that the forest management for their conservation and restoration through various forestry practices that tend to increase biological diversity and the structural diversity allow increasing the productivity of the temperate communities from forest ecosystems and making them more apt for the offer of environmental services, such as the provision of the water resource.

However, even when in many regions of the country forest exploitation is associated directly to the most successful experiences of conservation and development of forests, combining the provision of environmental services with forest exploitation is not something for which México is yet prepared. Therefore, the three ejido properties studied were accepted to participate in the PSAH because their status was “recovery or rest” in the ejidos’ management plan.

According to the information obtained in the research, one of the main reasons to participate in the PSAH was not only “to care and conserve the forest”, but rather the ejidos accepted to stop timber extraction during the five years of participation; they were only going to be kept at rest. This gave them the option of income for the ejidos for properties that they did not want to or could not extract timber from.

The current operation rules contemplate that for properties with timber-yielding forest management programs in place, only the polygons that are outside the areas with authorized felling would be eligible. The felling areas are only eligible when the petitioner demonstrates that he has the certification of good forest management (SEMARNAT, 2011).

This implies more requirements for the forest owners, since it is not enough to have just a forest management plan, but rather they must be in a CONAFOR registry where good forest management has been certified. This indicates that for CONAFOR the exploitation and the provision of environmental services are not entirely compatible, forcing the forest owners to conserve it only for the period when they receive backing from the program, and to opt to returning to timber extraction when they do not have commitments for conservation and permanence.

The researchers who have studied the PSA plans (Porras et al., 2008) currently designed, have found a clear trend toward eliminating the prohibition schemes for the use of resources and in their place generating others that compensate good management (Madrid-Ramírez, 2011); that is, there is an intention to promote the approach of “Active Conservation” and the payment of environmental services for good forest management.

Without a doubt, the future trend and best option of PSA plans is to compensate good management (active conservation) and not to just pay for conserving or reforesting (passive conservation), without making use of the natural resources available, since these are the inputs of any economic activity developed by humans and it is nearly impossible to leave them without using.

With regard to the works carried out in the field to conserve and improve the forest conditions, in the field visits it was verified that the conservation works were of good quality and fulfilled the specific objectives for which they were designed, such as control of hydric erosion, sediment control, moisture retention, protection, etc. As a whole, they also fulfilled the main objective, which was to improve the forest conditions even if in a limited way.

The field visits were a valuable tool to complement the information obtained in the interviews. Thanks to them, much of the information provided by the ejidatarios and the technical staff about the conditions of the properties backed by the PSAH could be confirmed.

In the case study, the PSTF and the ejidatarios interviewed agreed that the current conditions of the properties supported are better than before participating in the program. These improvements are based on three fundamental reasons: 1) in the properties benefitted no timber extractions were made during the time of the PSAH backing; 2) the ejidos complied with the commitments acquired through the operation rules of the PSAH because they performed conservation works and activities to improve the conditions of the forest (reforestations, conservation works for soil and water, prevention of fires, among others) with the PSAH resources; and 3) no serious disasters took place (such as the presence of fires, pests or diseases) or problems with clandestine felling.

The ejidos decided to take advantage again of their properties because the money they received from the PSAH is very little and they can only pay for some conservation activities and works that are not sufficient to give the forest the necessary care and maintenance. None of the resources granted by the PSAH were forked out directly to the ejidatarios. They only received payment for workdays to carry out the conservation tasks in the properties benefitted. Here the dilemma of the ejidatarios is to conserve without receiving significant economic benefits or to use these properties with forestry use to extract timber and receive incomes.

Regretfully there is no precise information, or photographic evidence, of how the properties were before participating in the program. There is only the information gathered by the PSTF and the ejidatarios regarding the conditions and what was observed in the field visits. However, it is undeniable that performing some of the conservation works for soil and water, reforestations, or some other activity impacts favorably in benefit of the forest.

An important piece of data that reveals the PSAH 2003-2007 evaluation is that 36 % of the beneficiaries agree that if the PSAH did not exist, they would use their land for agricultural and livestock purposes, and only a third of them would keep its forest use (González-Guillén et al., 2008).

The areas benefitted are at risk of being deforested because of a decision based on market factors and economic needs, despite the legal restrictions in place. The current situation of the properties benefitted by the PSAH in the three ejidos studies is the following: 1) The property in Ejido de Tequexquinahuac is being exploited under the Ejido’s Management Plan; 2) the property in Ejido de San Pablo Ixayoc is waiting to be exploited once the ejido’s Management Program is approved; and 3) the property in Ejido San Miguel Tlaixpan was declared a reserve area in closed season, and only small-scale extraction of moss, lama, and diseased wood is allowed. The latter is one of the areas that are best conserved within the Izta-Popo National Park.

After understanding the current state that the properties supported have, it can be concluded that the problem is not so serious, compared with the predictions there were regarding the future of forests: abandonment, deforestation, or change in land use. This did not happen in any of the three cases.

Conclusions

In 2005 the PSAH had an approach of “passive conservation”, which is why it only admitted properties considered “at rest” in the Management Plan of the three ejidos studied, even when they were not the ones at highest risk of being deforested. It has been shown in other studies that a well-managed forest property can provide the same or greater quantity and quality of environmental services that a property at rest.

The properties studied are in better conditions after having participated in the PSAH from 2005 to 2010, because of three reasons: 1) they were properties that were not exploited because they had the status of “at rest” in the ejido’s management plan; 2) the ejidos complied to a high degree with the commitments made with the PSAH when performing conservation works and activities with resources from the PSAH; and 3) there were no serious disasters in the period (pests, fires, or other problems).

The payments for environmental services granted by the PSAH were very small, which turned out to be unattractive for the ejidos, especially after having invested an important part in conservation works and not directing anything to benefitting the ejidatarios economically.

It is urgent that the PSAH becomes a profitable plan for the producers and that beyond the five years of backing, it assures continuing to receive income for the conservation of their forests; on the contrary, there is no guarantee that these properties will continue to provide the environmental services that they do now.

The participation of ejido properties in the PSAH does not guarantee that they will be conserved in the long term because the PSAH did not contribute to creating a permanent local mechanism for payments of environmental services. Despite this, the ejidos continue to perform conservation activities in the properties.

REFERENCES

Allan, Richard P., y Brian J. Soden. 2008. Atmospheric warming and the amplification of precipitation extremes. Science. Vol. 321. September 2008. pp: 1481-1484. [ Links ]

Bates, Bryson, Zbigniew W. Kundzewicz, Shaohong Wu, y Jean Palutikof. 2008. Climate Change and Water. Technical Paper of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC Secretariat. United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP). Ginebra, Suiza. 220 p. [ Links ]

CONAFOR. 2011. Panorámica sobre REDD+ en México. Taller sobre estimación de los costos de oportunidad y costos de implementación para el proceso de planificación nacional. Comisión Nacional Forestal. Unidad de Asuntos Internacionales y Fomento Financiero. [En línea] < [En línea] http://www.forestcarbonpartnership.org/fcp/sites/forestcarbonpartnership.org/files/Documents/PDF/July2012/04-REDD%2B%20en%20Mexico%20-%20J.A.Alanis%20et%20al.pdf > [Consultado el 15 de enero de 2013]. [ Links ]

Escobar, Samuel, y Oscar Palacios. 2012. Análisis de la sobreexplotación del acuífero Texcoco, México. Tecnología y Ciencias del Agua. ART-2012-02-05. Abril-junio 2012. [ Links ]

González-Guillén, Manuel. 2006. Evaluación del Programa de Pago de Servicios Ambientales Hidrológicos (PSAH): Ejercicio fiscal 2005. Colegio de Postgraduados y Comisión Nacional Forestal. México. 170 p. [ Links ]

González Guillén, Manuel. 2008. Evaluación externa de los apoyos de los servicios ambientales: Ejercicio fiscal 2007. Evaluación de impactos. Colegio de Postgraduados y Comisión Nacional Forestal. México. 231 p. [ Links ]

Kawulich, Barbara B. 2005. La observación participante como método de recolección de datos. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research [On-line Journal], 6(2), Art. 43, Disponible en: <Disponible en: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0502430 >. [Consultado el 26 de enero de 2012]. [ Links ]

López-Morales, C. 2012. Valoración de servicios hidrológicos por costo de reemplazo: Análisis de escenarios para el Bosque de Agua. Dirección General de Investigación en Ordenamiento Ecológico y Conservación de Ecosistemas, Instituto Nacional de Ecología. México, D.F. Disponible en: <Disponible en: http://ine.gob.mx/descargas/dgioece/doc_bosque_de_agua.pdf >. [Consultado el 10 de enero de 2013]. [ Links ]

Madrid-Ramírez, Lucia. 2011. Los pagos pos servicios Ambientales Hidrológicos: más allá de la conservación pasiva de los bosques. Conservación Ambiental. Vol. 3. Núm. 2. pp: 52-58. [ Links ]

Montes, C., y O. Sala. 2007. La Evaluación de los Ecosistemas del Milenio. Las relaciones entre el funcionamiento de los ecosistemas y el bienestar humano. Ecosistemas, 16 (3). pp: 137-147. [ Links ]

Návar-Chaídez, José de Jesús. 2011. Los bosques templados del estado de Nuevo León: el manejo sustentable para bienes y servicios ambientales. Madera y Bosques. 16 (1), 2010. pp: 51-69. [ Links ]

Porras, Ina, Maryanne Grieg-Gran, y Nanete Neves. 2008. All that glitters: A review of payments for watershed services in developing countries. Natural Resource Issues No. 11. International Institute for Environment and Development. London. 129 p. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, G. 1996. Metodología de la investigación cualitativa. Ed. Aljiba. Barcelona, España. 378 p. [ Links ]

Ruiz-Pérez, M., C. García-Fernández, y J. A. Sayer, 2007. Los servicios ambientales de los bosques. Ecosistemas. Vol.16. Número 3. pp: 81-90. [ Links ]

Salkind, Neil J. 1999. Métodos de investigación. 3ra edición. Ed. Prentice Hall. México, D.F. 380 p. [ Links ]

SEMARNAT. 2003. Acuerdo que establece las reglas de operación para el otorgamiento de pagos del Programa de Servicios Ambientales Hidrológicos. Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. Diario Oficial de la Federación. 3 de octubre de 2003. México. [ Links ]

SEMARNAT. 2011. Reglas de Operación del Programa ProArbol 2012. Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. Diario Oficial de la Federación. 21 de diciembre de 2011. México, D. F. 89 p. [ Links ]

Sultana, Zakia, y Paulin Coulibaly. 2011. Distributed modelling of future changes in hydrological processes of Spencer Creek watershed. Hydrological Processes. Vol. 25. Issue 8. April 2011. pp: 1254-1270. [ Links ]

Tague, Christina, y Gordon E. Grant. 2009. Groundwater dynamics mediate low-flow response to global warming in snow-dominated alpine regions. Water Resources Research. Vol. 45. W07421. 12 p. [ Links ]

Taylor, Richard G. 2013. Ground water and climate change. Nature Climate Change. Vol. 3. April 2013. pp: 322-328. [ Links ]

Received: November 2013; Accepted: November 2016

text in

text in