Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Agricultura, sociedad y desarrollo

Print version ISSN 1870-5472

agric. soc. desarro vol.13 n.4 Texcoco Oct./Dec. 2016

Articles

Pension program for the elderly in two rural communities: Santa María Tecuanulco and San Jerónimo Amanalco, Texcoco, México

1Colegio de Posgraduados. Campus Montecillo. Desarrollo Rural. Carretera México-Texcoco, Km. 36.5. Montecillo, Texcoco, Estado de México. 56230. (eduardo.delao@colpos.mx) (ljs@ colpos.mx) (mjimenez@colpos.mx).

2Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Preparatoria. km 38.5 carretera. México-Texcoco. Chapingo, Estado de México. 56230. (hiperbóreo_jorge@hotmail.com)

The federal Pension Program for the Elderly is analyzed in two rural communities of the municipality of Texcoco, Estado de México: Santa María Tecuanulco and San Jerónimo Amanalco. The senior citizen (SC) and his/her physical, social and economic condition are studied, and the difficulties of the program are identified, as well as their causes and consequences. The main problems for the SC are that he/she doesn’t have a pension and is incapable of attaining sufficient income for a dignified life, expressed in low income and health deterioration. These factors are manifested in a limited exercise of his/her social rights, economic and functional dependence on third parties, and low self-esteem (depression). The research uses the mixed method: qualitative and quantitative; techniques of social research, observation and participant observation are applied; the information was obtained through a questionnaire with 58 questions, interviewing 78 SCs. The results show that the federal program provides income to improve their quality of life, but does not fulfill the needs and expectations of the SC. The lack of documents requested to be considered part of the program is frequent; most SCs do not have a birth certificate, and the program rejects them without offering a different alternative, so they are not incorporated, and there is scarce empathy when catering to this population.

Key words: senior citizen; quality of life; rural community; pension

El programa federal Pensión para Adultos Mayores se analiza en dos comunidades rurales del municipio de Texcoco, Estado de México: Santa María Tecuanulco y San Jerónimo Amanalco. Se indaga sobre el adulto mayor (AM), su condición física, social y económica, y se identifica la problemática del programa, sus causas y consecuencias. Los principales problemas del AM son que no cuenta con pensión y su incapacidad de conseguir ingresos suficientes para tener una vida digna, expresada en bajos ingresos y deterioro de su salud. Estos factores se manifiestan en un limitado ejercicio de sus derechos sociales, dependencia económica y funcional de terceros, y una baja autoestima (depresión). La investigación utiliza el método mixto: cualitativo y cuantitativo; se aplican técnicas de investigación social, observación y observación participativa; la información se obtuvo a través de un cuestionario con 58 preguntas, entrevistando a 78 AM. Los resultados muestran que el programa federal proporciona un ingreso para mejorar su calidad de vida, pero no cumple con necesidades y expectativas del AM. La falta de documentos solicitados para ser considerado parte del programa es fecuente; la mayoría no tiene acta de nacimiento, el programa los rechaza sin ofrecer otra alternativa y no son incorporados, hay poca empatía al atender a esta población.

Palabras clave: adulto mayor; calidad de vida; comunidad rural; pensión

Introduction

Same as other nations, México is in the process of ageing based on demographic projections, and it is anticipated that the number and proportion of elderly people will increase with regards to other younger groups of population, representing a challenge for the policies of social and economic development, as well as for the programs of poverty reduction. The factors that contribute to this process are the reduction of mortality rates and the decrease in the fertility rate; technological and medical advancements influence life expectancy (Rubio and Garfias, 2010; Cervantes, 2013).

Demographic ageing is understood as the absolute and percentage growth of the population in advanced ages and it is a dynamic process through time and space that acquires social, economic, political and institutional dimensions. In various studies 65 years old is considered as the age limit for the stage of seniority or old age (Jasso-Salas et al., 2011).

The vulnerability of senior citizens should be mitigated with access to social security. However, the pensions that are instruments for savings linked to the individual’s salary throughout their work life contribute to containing the decrease of income in old age, but they do not reach all of this population; of seven million SCs, only 1.3 are pensioned or retired, and 5.7 million do not get any income (INEGI, 2010).

Nevertheless, in México there is a complex multiplicity of pension systems, which include special systems for private workers and employees of federal and state governments, and public enterprises, as well as special regimes for public universities, development banks and municipalities. This situation is present in the formal labor market, contrasting with broad sectors of the population who work informally.

The International Labour Organization reports the participation of SC people in 39 %. The rates of participation of older workers in countries of the OECD averaged 63 % (2008) and report differences between countries, including Japan and the United States. The main reason why this group is active in the market is the growth of women’s participation in the workforce, even if there is still a large difference between the sexes (OCDE, 2012).

According to demographic indicators, the population’s ageing decreases in rural zones, while the SC (2000) increases in the urban area, 26 % and 74 %, respectively. Therefore, projections (2030) show that in rural regions this population will be reduced to 18 % and in the urban scope it will reach 82 % (CONAPO, 2012). In face of this situation, the Mexican government through policies of social development establishes programs for attention to this specific group, through diverse actions, among them the promotion of employment, established by the National Institute of the Elderly (Instituto Nacional de las Personas Adultos Mayores, INAPAM), Training Program for Work and Free Time Occupation, Old Age and the Pension Program for the Elderly.

A direct consequence of this ageing is the gradual increase of the average age of the Mexican population from 28 years in 2005 to 30 years in 2010; based on projections, the tendency will be 42.7 years in 2050 (CONAPO, 2012). It is also expected that by 2030 the percentage of elderly people will be 12.5%, increasing to 22.6 % by 2050 (Cervantes, 2013) Table 1 and 2.

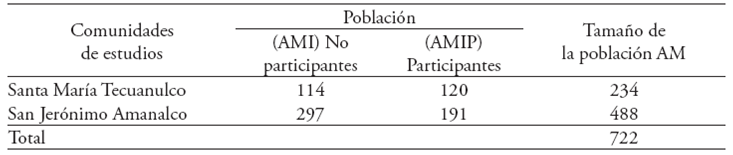

Table 1 Base population of SCs per community.

Source: Based on the Delegation and municipal DIF, INEGI (2010).

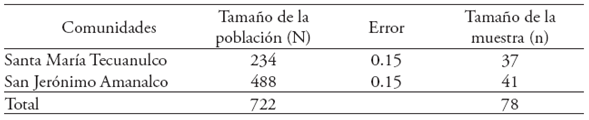

Table 2 Size of the sample: Santa María Tecuanulco and Amanalco.

Source: based on data from the Delegation, DIF municipal and INEGI (2010).

This situation is due in part to the decrease in mortality that originates a progressive increase in life expectancy; an increasingly larger number of people reach advanced age. On the other hand, fertility decreases which is reflected in the medium term, both in a lower number of births and in a systematic reduction of the proportion of children and youth in the total population. The combination of both trends leads to demographic ageing, a fact expressed in a narrowing of the base and widening of the point of the population pyramid (Rubio and Garfias, 2010).

According to population pyramids, there are more senior citizens in México each year; the growth is reflected more in the group of women (because they live longer than men). One of the most worrying risks of demographic ageing is accompanied by other phenomena of social character and related to impoverishment. The risk is associated to the reduction of work opportunities for people of old age, gradual loss of health, insufficient coverage of the national security system and greater dependence on their family members (Brambila, 2006).

The SC population is vulnerable because of the fall in economic income, at the end of their productive life along with health deterioration, resulting from chronic disease. The problem is worsened even further in rural and marginal communities, for the pension system leaves out an important number of SCs, who do not have access to the benefits granted by social security institutions (Rubio and Garfias, 2010).

The SC is a person who is characterized by belonging to the group of people older than 65 years of age; nowadays he/she plays a very important role in society, even if his/her relevance is not recognized. Because of this, the actions can be directed at addressing a specific need: healing and protecting the people who need attention from the government or private institutions that complement the work of the State (Chossudovsky, 2002).

When considered a SC, a person who may offer his/her knowledge to society or to the human group that composes it, whether child, young person or elderly in activity, the tasks that are organized in function of the senior citizen acquire a different sense.

According to Linton (1992), the task that the SCs play inside the family and in the daily social interaction represents all the age and sex groups which have rather many limitations inside the family and society, so these are not the exception.

Within this context the following question is set out: What is the quality of life that SCs seek? Thus, when we refer to their condition, we are not only referring to providing services, but also to understanding the high level of wellbeing, satisfaction and self-esteem, and at the same time, to promoting their independence and personal development. The concept “quality of life” takes on special relevance when referring the SC, because the services received are limited to welfare levels, only covering the basic necessities instead of considering the person as an integral being, and to having the rights of access to resources in their search for their own wellbeing (Sen, 1992).

Because of this situation, the main problem of the person who does not have a pension is in his/ her inability to attain greater benefits to cover his/ her basic needs and to have a dignified life. In turn, these factors are manifested in a limited exercise of his/her social rights, economic dependency, and low self-esteem and depression (Fierro, 1999).

The Ministry of Social Development (Secretaría de Desarrollo Social, SEDESOL) instituted the Pension Program for the Elderly (formerly 70 y más). One of its purposes is to grant financial help to those who do not have a pension or retirement fund; however, the practice indicates that this support does not reach those who need it or is insufficient to cover the basic needs of the SC. The program considers a SC of 65 to 75 years and people older than 76 years, since it cannot be considered that the working, physical, social and health capacities are the same than those of a person who is 65 years old (SEDESOL, 2014).

Study area: localities of the municipality of Texcoco, Estado de México

The municipality of Texcoco is part of Estado de México, state of the Mexican Republic that has the highest number of people 60 years and older (7.7 % of the total population, 2010), situation which can entail, approximately, that one to four households in the entity have a senior citizen (INEGI, 2010).

The communities under study are part of the 54 localities that make up the municipality and they are located in its mountainous area. They were chosen due to a series of reasons, primarily because of their concrete characteristics of geographical location (mountain towns), because they share agricultural techniques (terraces), and are devoted to sowing agricultural products (flowers, fruits and basic grains); in addition, they share traditions and social and communal activities (tasks or mutual help), among other considerations (Sokolosky, 2010). They also have social programs at the federal level, which is the Pension Program for the Elderly, state-wide and municipal; the latter supplies food stamps.

The SC population in the two communities increases following the national, state and municipal trend. In both localities, the growth of this population sector doubled in only one decade, from 2020 to 2030 (INEGI, 2010). The study sets out the objective of analyzing the Federal Pension Program for the Elderly in the communities of Santa María Tecuanulco and San Jerónimo Amanalco, in the municipality of Texcoco, Estado de México. During the research process, residents from both towns agreed to participate, responding with friendly and cordial manners.

In the communities, the rate of SCs with a pension plan is very low, even lower than the national mean (8 %), showing that there are rural zones that are economically marginalized in eastern Estado de México (Gemeren, 2010).

When dividing by gender, the survey shows that 29 % are men and 71 % are men; the information reflects that for every man there are 2.25 women, and the national trend is that the female population is higher because women outlive men, so there is a feminization of the population taking place.

Methodology

The study uses a mixed method: qualitative and quantitative. In the qualitative, social research techniques are applied: observation and participant observation; it is descriptive because it was carried out through the analysis of field information (Hernández et al., 2010). It begins with a documentary revision: bibliographic material, newspaper material, internet consults, administrative operative data and statistics from SEDESOL’s Pension Program for the Elderly, with the purpose of understanding the physical, economic and social state of the SCs in the two communities. A comparative analysis of the people who have support from the program and those who are not registered in it was also performed.

For the quantitative approach a 58-question questionnaire was designed, distributed into six sections that incorporate: social-demographic aspects, physical state of the senior citizen, financial state, Pension Program for the Elderly, characteristics of their household, and recreational activities. The information was obtained by interviewing 78 senior citizens.

With authorization from local and municipal authorities in the communities of study and the DIF from the municipality of Texcoco, Estado de México, the participant research was carried out. In terms of the incorporation that integrates rural senior citizens, the researcher as participant observer was included in meetings and workshops that the municipal DIF authorizes.

The SC population that resides in the two communities, according to the Delegation from each community and the municipal DIF includes 722 people, taking into consideration those registered (AMIP) and not registered (AMI) into the Pension Program for the Elderly. (Table 1).

The sample to gather field information was carried out through simple random sampling. After defining the sample, the survey was applied to obtain data and estimate the parameters for their interpretation. The following hypothesis was set out: rural communities in the study area follow the national demographic tendency of the population ageing; there are increasingly more SCs, so the social programs devoted to this sector of the population are necessary for those who do not have any pension or retirement fund.

The values from the sample were obtained with the information provided by the active listing of the Pension Program for the Elderly, as well as the census of SCs in the two communities and the electoral roll of the Electoral Institute of Estado de México (IEEM, 2010). The sample or population size (N) is 722 senior citizens who reside in Santa María Tecuanulco and San Jerónimo Amanalco, municipality of Texcoco, Estado de México.

The last part corresponds to the creation of a database, analysis of information, and presentation of results by using graphs and tables elaborated with Microsoft Excel 2010; these include descriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation, mode, frequency distribution and graphs (Infante and Zarate, 2005).

Results and dIscussIon

According to the information obtained in the field, the average age of those interviewed is 74 years and the standard deviation is 5, which means that most of the ages are within the interval (69, 79).

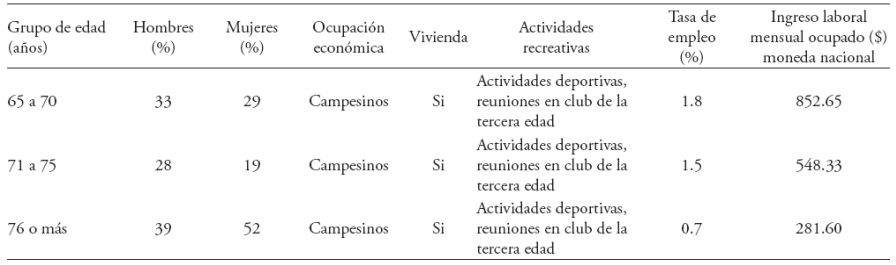

Therefore, the most repetitive is 76 years; likewise, the lowest age of SCs is 65 years, while the highest reached is 90 years. (Table 3).

Table 3 Characteristics of Senior Citizens in the communities studied.

Source: direct research, summer of 2014.

Most of the interviewees from the two communities are small-scale producers for auto-consumption, poor peasants and they are the oldest; however, through the Old Age Club, jointly they carry out various recreational activities in the local delegation; among them, physical exercise according to their age stands out, as well as manual activities and social meetings where they share meals, music and dance; what stands out most is the harmonious coexistence, with cordiality and cooperation within the group.

According to the population per gender, there are more senior women 71 years and older in comparison to men; they represent 71 % of those interviewed, which indicates that the feminine population is more than double compared to the masculine population and which have a longer life expectancy. Elderly women in this group of SCs do not receive income. Due to traditional gender roles, destined to the house chores and to contributing to the family domestic support, women have less probability of working to generate income and savings to allow them to sustain their financial needs in old age.

The historical background of the two communities of study is of Pre-Hispanic origin. Therefore, the native language is taken into account: 82 % of senior citizens speak Náhuatl in addition to Spanish, while 18 % only speak Spanish, situation that indicates that for each SC who only speaks Spanish there are 4.6 SCs who speak Spanish and Náhuatl. This indicates the transmission of language; they still conserve some traditions from their ancestors such as speaking in their native language (Sokolosky, 2010).

On the other hand, in Santa María Tecuanulco there is a bilingual primary school; its purpose is the transmission and conservation of the Náhuatl language. The scope of attention extends to other towns of the region and the largest group of Náhuatl speakers resides in San Jerónimo Amanalco. It is important to highlight that these localities in the mountain have a musical tradition; an important group of young and middle-aged people are devoted to playing wind instruments and participate in musical groups, orchestras and symphonies in Mexico City and in regional festivities.

When considering the degree of schooling reached, it is incomplete education; they report that they learned the basic contents because they had to go work to help sustain the family. There are 72 % of senior citizens who know how to read and write; in contrast, 28 % do not know how to read. Therefore, out of each SC who cannot read, 2.5 people manifest that they can.

Concerning the marital status of the population interviewed, 51 % reported that they are widowers, 37 % are married, 8 % live in domestic partnership, 3 % are divorced and there is one single man (1 %). In senior women, widows predominate because they have a longer life expectancy than men and they quickly tend to adapt to their situation of living alone, accompanied by grandchildren or other family members. In some cases this situation can imply abuse, violence, other types of threats and risks for their health and wellbeing. In contrast, men live married in comparison to women in the group of senior citizens of middle and advanced age (Wong and González, 2011).

With regards to housing, there is an average of four people per family interviewed, and it was found that most people live in a single household with a frequency of 16 cases. Likewise, SCs who live alone were also found; however, others live with their families, they report up to 10 members (extended family) in the same household and they coexist with young people, children and adults, forming what is known as multi-generational households. It is relevant to mention that in both communities, the SCs have houses of their ownership.

The main sources of income of the SCs are generated by activities carried out in the countryside, based on auto-supply and complementing their income with non-agricultural activities. They are still peasant families, they own a plot and have experience in farm tasks where they work for family consumption (Magdaleno et al., 2014); they grow basic grains (49%): white maize (Zea mays L.) and bean (Phaseolus vulgaris, Lin). The older peasants who are devoted to cultivating their land sometimes have received some backing from the state government to cultivate their land (Zarazúa, 2011).

Other activities are commerce (17 %), domestic employees (5 %), maquila workers (3 %), and construction (1 %). The interviewees who do not have work (26 %) request financial support and provision from family members and friends. The characteristics of these occupations allow a gradual retirement from work or to extend it until their health allows, conserving control of their productive resources. However, for those devoted to agriculture the land represents their patrimony and its production contributes to the family food supply.

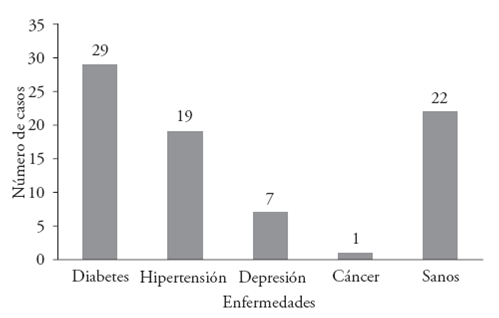

Based on the most frequent illnesses of people in the study zone, it is important to consider health because with time a gradual deterioration in the physiological state of people takes place. In the communities of study there are SCs with diabetes (29), high blood pressure (19), depression (7), cancer (1), and there are also healthy people (22). Of the total people ill, 87 % receive medical treatment, compared to 13 % who do not. Diabetes is the chronic illness that occupies the first place, and this piece of data coincides with the national trend (Ham-Chande, 2011). (Figure 1).

Source: direct research, summer of 2014. (No se menciona en el texto)

Figure 1 Most frequent chronic illnesses.

Some of the physical limitations found in the SCs interviewed are: they do not walk (6 %), they cannot see (1 %) and have hearing problems (5 %); most of them (87 %) do not present physical limitations. In the field, it was observed that in the case of elderly peasants in the two communities, retirement from their activity is not marked by age (old age) in chronological terms. They remain active, as long as there are no physical limitations that prevent their independence.

With regards to social security, most of the SCs have Seguro Popular; 88 % correspond to the population of study, only 5 % have IMSS and 6 % of those interviewed do not have any type of social security. These data indicate that most SCs at the community level do not have social security, situation that is reflected more in rural localities. In their working phase, this population does not have formal employment, but rather they are devoted more to agriculture, small-scale commerce and selfemployment.

From the study population, only 5 % have a retirement plan that the IMSS offers, while 95 % does not have a pension or retirement plan, so they have to attain income through their own means. Most of the SCs in the communities of study are registered in the Pension Program for the Elderly, 77 persons; only one case of those interviewed is not registered, because he is pensioned through IMSS with a monthly amount over that allowed ($1090.00).

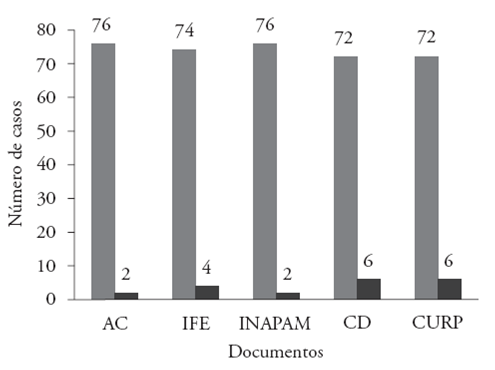

When considering the integration of documents for the Pension Program for the Elderly, 95 % SCs from the communities of study have the necessary official documents to become incorporated into the program; the other 5 % does not have these papers. This situation indicates that when a senior citizen is not registered to the program, it is mainly because he/she is not eligible as a result of some inefficiency in the operation system or from being registered to another valid program (PROSPERA, food stamps, others). (Figure 2).

Notes: AC: birth certificate; IFE: electoral identity card; INAPAM: senior citizen identity card; CD: proof of address; CURP: population registry identity card.

Source: direct research, summer of 2014.

Figure 2 Integration of documents for the Pension Program for the Elderly.

The SCs (96 %) destine the help granted by the program to food and to purchase medicine; this means that they don’t make ill use of the resource received because they invest it in basic needs. The amount of the Pension Program for the Elderly is $1160 per two months; that is, $580 monthly, which corresponds to 29 % of the monthly general minimum wage ($2019) or $19.3 daily, which proves that this amount is insufficient to support the SC.

The program can barely cover part of the basic needs of the SC, such as purchasing food; when the support does not arrive they resort to sowing crops for auto-consumption. Thus, many of them do not have a balanced diet and it is frequent for them to eat only twice a day.

Concerning satisfaction with the program, 92o% of the senior citizens are not satisfied with the program; the main reasons reported are: a) the first support took at least six months to arrive; b) there are many delays in the payments; c) reactivations must be processed as the first time registration; d) instructions about payment card management are not clear; and e) the amount paid is insufficient to cover their basic needs.

ConclusIons

The characteristics of the senior citizens interviewed, considering the sociodemographic information obtained in the two communities are the following:

The average age of the SCs is 74 years. When dividing by gender, 29 % are men and 71 % are women. This situation reflects that there are 2.25 women per each man, which shows the national tendency that highlights the feminization of the population.

The SCs (82 %) speak Náhuatl, and only a smaller group speaks Spanish (18 %). Therefore, it can be seen that for each older person who speaks this language, 4.6 SC can communicate in both languages. The degree of schooling is incomplete primary: 72 % SCs know how to read and write, and 28 % cannot read; 2.5 people say they can read, for each one who does not.

With regards to the marital status, 51 % of those interviewed are widowers, 37 % are married and the remaining percentage is in domestic partnerships or they are divorced. The women tend to be widows because their life expectancy is greater than that of men.

The home ownership of the SCs stands out; most of them live with family, with an average of four members. There are also households with extended families where grandparents, parents, children, daughters-in-law, grandchildren and greatgrandchildren coexist, and they are solidary and collaborative with the SC. Because of these causes, the family continues to be the main institution responsible for the care and integration of the SC.

In relation to the pension or retirement program:

At the community level, most of the SCs do not have social security, but they have attention from Seguro Popular (88 %) and IMSS (6 %); other elderly people do not have these services (6 %).

Most of the interviewees (95 %) do not have any type of retirement plan, but they are registered with the Pension Program for the Elderly; some (5 %) have a pension plan offered by IMSS.

The SCs registered to the Program have the official documents necessary for their attention; the ones not registered are due to the inefficiency in the program’s operation, they lack official documents, or else, they are registered to other backing, among them PROSPERA, food stamps and others.

Of the support received from the Program, 96o% of the SCs destine it to their diet or to purchase medicine. When the support does not arrive, they frequently resort to satisfying the family diet with production that is generated from agriculture.

The SCs (92 %) report not being satisfied with the program because the help comes with delays, the management of payment cards is complicated, and the amount received is insufficient to cover their basic needs; in addition to despotism and indifference from the public servants, the SCs invest up to two hours in clarifications or questions about the program.

The program corresponds to planning and design from a desk, in order to gain popularity; however, this does not help to improve the quality of life of the SCs in the rural scope.

Regardless of their age and of their being ill, they must continue working for their sustenance, and for most of the SCs from the communities their main source of income is agriculture.

The rural communities studied follow the national demographic tendency in terms of population ageing. Therefore, the social programs devoted to this sector are necessary for those who do not have any pension or retirement plan, although they require significant changes for their proper functioning.

The social programs in México contribute what the government dictates (public policies), without carrying out a study of the population’s needs, and without attaining the objectives of the social programs, which is the social and economic development of one of the most vulnerable sectors.

Literatura citada

Aguilar, Luis F. 1996. La hechura de las políticas. México, Miguel Ángel Porrúa. pp: 15-84. [ Links ]

Brambila, José Luis. 2006. En el umbral de una agricultura nueva. México, Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. pp: 20-65. [ Links ]

Cervantes, Lilian. 2013. Apoyos en hogares con al menos un adulto en el Estado de México. In: Papeles de Población, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. Toluca. Vol. 19, núm 75, enero- marzo. pp: 1-30. [ Links ]

CONAPO (Consejo Nacional de Población). 2012. Proyecciones de Población 2010-2050. México. [ Links ]

CONAPO (Consejo Nacional de Población). 2012. Dinámica demográfica 1990-2010. Proyecciones de la población 20102030; y Programa Nacional de Población (PNP) 2014-1018 en: www.conapo.gob.es/conapopublicaciones. [ Links ]

Chossudovsky, Michel. 2002. Globalización de la pobreza y nuevo orden mundial. México, Siglo XXI. pp: 10-50. [ Links ]

Fierro, Alfredo. 1999. El desarrollo de la personalidad en la adultez y la vejez. In: Desarrollo Psicológico y Educación, Vol. 1. Psicología Evolutiva. Madrid, Alianza editorial. [ Links ]

Gemeren, Edwin Van E. 2010. La Participación de los Adultos Mayores: Problemas de México. México. El Colegio de México. pp: 258-306. [ Links ]

Ham-Chande, Roberto. El envejecimiento en México: el siguiente reto de la transición demográfica. Tijuana, B.C, El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, 2011 [ Links ]

Hernández S, Roberto, Carlos Fernández C., y Pilar Baptista. 2010. Metodología de la Investigación (5ª. edición), México, Mc Graw Hill. pp: 24 -30. [ Links ]

Infante, Said, y G. Zarate. 2010. Métodos Estadísticos (8ª reimpresión) México, Editorial Trillas. pp: 11-16. [ Links ]

IEEM (Instituto Electoral del Estado de México). 2010. México. [ Links ]

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática). 2010. Censo Nacional de Población y vivienda 2010. México. [ Links ]

Jasso-Salas, Pablo. Cadena-Vargas, Edel. Montoya-Arce, y B. Jaciel. 2011. Los adultos mayores en las zonas metropolitanas de México: desigualdad socioeconómica y distribución espacial, 1990-2005. In: Papeles de Población, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. Vol. 17, núm. 70, octubre-diciembre. pp: 81-124. [ Links ]

Linton, Ralph. Status y rol. In: Antropología. Lecturas (2ª. edición). España, Mc. Graw Hill. 280 p. [ Links ]

Magdaleno-Hernández, Edgar. Mercedes A. Jiménez Velázquez, Tomás Martínez Saldaña, y Bartolomé Cruz Galindo. 2014. Estrategias de las familias campesinas en Pueblo Nuevo, Municipio de Acambay, Estado de México. In: Agricultura, Sociedad y Desarrollo. México, Colegio de Postgraduados, Vol. 11, Núm. 2. pp: 167-179. [ Links ]

OCDE. 2012. Panorama de las Pensiones 2011. Sistemas de Ingresos al retiro en los países de la OCDE Y DEL G20. Santiago de Chile-Paris, OCDE, Corporación de Investigación, Estudio y Desarrollo de la Seguridad Social CIEDESS. pp: 57-61. [ Links ]

Rubio M, Gloria y Francisco Garfias. 2010. Análisis comparativo sobre los programas para adultos mayores en México. Naciones Unidas. Santiago de Chile. pp: 16-22. [ Links ]

Sen, Amartya. 1992. Nuevo examen de la desigualdad. Madrid, Alianza Editorial. pp: 7-69. [ Links ]

SEDESOL (Secretaría de Desarrollo Social). 2014. Programa Pensión para Adultos Mayores, México. www.sedesol.gob.mx [ Links ]

Sokolovsky Jay. 2010. La respuesta social y económica a la globalización en una comunidad indígena de la sierra texcocana. In: Texcoco en el nuevo milenio. Magazine, R y Martínez S.T (coord) México. Universidad Iberoamericana. 360 p. [ Links ]

Wong, Rebeca, y César González G. 2011. Envejecimiento demográfico en México: consecuencias en la discapacidad. In: Coyuntura Demográfica. México, Núm. 1, noviembre. www.somede.org/coyunturademográfica/número1/. pp: 40-43. [ Links ]

Zarazúa Escobar, y J. Alberto. 2011. El Programa de Apoyos Directos al Campo (PROCAMPO) y su Impacto sobre la Gestión del Conocimiento Productivo y Comercial de la Agricultura del Estado de México. In: Agricultura, Sociedad y Desarrollo, Volumen 8, Nº 1. pp: 88-105. [ Links ]

Received: February 01, 2015; Accepted: February 01, 2016

text in

text in