Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Agricultura, sociedad y desarrollo

Print version ISSN 1870-5472

agric. soc. desarro vol.13 n.2 Texcoco Apr./Jun. 2016

Articles

Potential and restrictions of backyard poultry production for food security in Guerrero, México

1 Centro de Investigaciones Económicas, Sociales y Tecnológicas de la Agroindustria y la Agricultura Mundial (CIESTAAM) de la Universidad Autónoma Chapingo (UACh). km 38.5 carretera México-Texcoco, Chapingo, Estado de México. México. 56230. (bcruz@ciestaam.edu.mx) (manrrubio@ciestaam.edu.mx) (hsantoyo@ciestaam.edu.mx) (enriquemartinez@ciestaam.edu.mx) (naguilar@ciestaam.edu.mx).

The potential and restrictions of poultry production supports promoted by the Strategic Food Security Program (Programa Estratégico para la Seguridad Alimentaria, PESA) were analyzed, in regions of high marginalization in Guerrero, México. In the year 2010, 107 Family Poultry Production Units (Unidades Avícolas de Producción Familiar, UAPF) with at least one year of operation were surveyed, from a registry of 2268 projects. The results showed that after 18 and 30 months of operation, only 6 % of the UAPFs ceased to operate, although close to 47 % decreased significantly and continued functioning because PESA granted additional supports of up to three years if they did not abandon the activity. Later, in 2012, information was collected from 51 of these UAPFs. It was found that after 48 months of operation, 39 % of the UAPFs had stopped poultry production, 32 % had decreased, and only 29 % of these showed viability. These results suggest avoiding massive public policies for food production under backyard conditions, and considering the restrictions which families face to guarantee the sustainability of the projects.

Keywords: family agriculture; backyard poultry; development of abilities; rural poverty; public policies

Se analizó el potencial y las restricciones de apoyos avícolas promovidos por el Programa Estratégico para la Seguridad Alimentaria (PESA) en regiones de alta marginación en Guerrero, México. En el año 2010 se encuestó a 107 Unidades Avícolas de Producción Familiar (UAPF) con al menos un año de operación, provenientes de un padrón de 2268 proyectos. Los resultados mostraron que después de 18 y 30 meses de operación, sólo 6 % de las UAPF dejaron de operar, y aunque cerca de 47 % decrecían significativamente y seguían funcionando porque el PESA otorgaba apoyos adicionales hasta por tres años si no abandonaban la actividad. Posteriormente, en 2012 se recabó información de 51 de estas UAPF. Se encontró que después de 48 meses de operación, 39 % de las UAPF habían dejado la avicultura, 32 % decrecían, y sólo 29 % de ellas mostraban viabilidad. Estos resultados sugieren evitar políticas públicas masivas para la producción de alimentos en condiciones de traspatio, y considerar las restricciones a las que se enfrentan las familias para garantizar la sostenibilidad de los proyectos.

Palabras clave: agricultura familiar; aves de traspatio; desarrollo de capacidades; pobreza rural; políticas públicas

Introduction

Food security regained relevance as a result of the volatility of food prices (Dorward, 2013). According to FAO (2014), the real prices of foods were the highest in nearly 30 years. This rise in prices provoked serious privation, suffering and social protest, particularly among the poorest population (FAO, 2014), for they direct the greatest part of their earnings to purchasing food (Dorward, 2013).

In the evaluation report of the social development policy (CONEVAL, 2011), the incidence of population with shortage of access to food was the only one of social character that increased. And this is because poor families face price increases by consuming less expensive and less nutritious foods, which can have lifelong effects on the physical, social and mental welfare of people, particularly children and young people.

Although the prices of agricultural products have decreased since their maximum figures, food prices continue to be high and they are not expected to decrease to the levels recorded in 2007-2008 during the next decade. In fact, OCDE/FAO (2013) foresee that in the next 10 years the average prices of cereals will be 50 % higher in real terms than the mean value of the 1998-2002 period. The same report warns that in the coming years episodes of extreme volatility cannot be dismissed, similar to the increase experienced in 2008, especially because the prices of basic products depend increasingly more on the costs of energy and petroleum, and the experts warn about a higher variability in climate conditions. The economic recovery, a greater demand for food in developed countries, and the market growth of biofuels are key elements to strengthen the prices and the markets of basic agricultural products in the medium term.

Facing a situation as the one described, it is necessary to take public policy measures to improve food security, particularly that of poor rural families, more so when an increase in food prices would affect negatively poor families to a greater extent than rich ones (Dorward, 2013); for example, simulations made by Levin and Vimefall (2015), regarding the price of maize in Kenya, indicate that the effect on the level of poverty would be up to double in rural areas. Facing this scenario, two large policy approaches are identified: providing access to food to the most vulnerable people or helping small-scale producers to raise their production and obtain higher income. These approaches that are conceptually complementary can actually compete, particularly when they are designed and implemented with the same target population and in the same territory.

Under the first approach, the best policy is to transfer money in cash to the poor in a conditioned manner, because it allows them to adjust their diet to the relative prices and does not limit the income of those who supply foods to the poor. In the long run, these transferences offer the correct incentives to food producers to increase their production (Levy and Rodríguez, 2005; BID, 2008; Mayer-Foulkes and Larrea, 2007). A clear example of this approach is “Oportunidades”, a Mexican program that combats poverty through which money is delivered to the poor households in exchange for them sending their children to school, increasing their body weight, being up to date with the vaccination calendars, and attending health clinics1. The idea behind a conditioned monetary transfer is that it mitigates the current poverty (through complementary income), at the same time that it prevents future poverty (by creating incentives for families to invest in human capital).

Under the second approach, it is considered that conditioned transferences can be insufficient to overcome dietary and patrimonial poverty, particularly in rural areas, because they do not impact the development of the families’ abilities to produce their own foods, undertake productive projects to generate income, or improve the conditions of the households and the environment (Alvarado Bahena, 2010). By virtue of this, SAGARPA implemented the Strategic Food Security Program (Programa Estratégico de Seguridad Alimentaria, PESA) in rural municipalities and communities of high and very high marginalization. This program launched its pilot phase in 2002 and has the technical and methodological support of the FAO. The objective of “contributing to the development of abilities of people and to their family agriculture in rural communities of high and very high marginalization, to increase agricultural and livestock production, innovate production systems, develop local markets, promote the use of foods and the generation of employment, in order to achieve their food security and an increase of income”, has been set out (Gobierno de México, 2010).

The PESA methodology emphasizes participative promotion and planning, with the purpose of identifying, formulating, managing, implementing and following-up family projects that allow contributing to improve the health in the household (through the establishment of firewood-saving stoves, silos to store grains and rain water capture systems), producing foods of agricultural or livestock origin for auto-consumption, and generating income. Therefore, the objective of “developing abilities” is established, in the populations that reside in communities of high marginalization through Rural Development Agencies (Agencias de Desarrollo Rural, ADR),2 which promote, in a participative manner, the micro-regional development through local projects and management.

To finance these projects, PESA has received growing public resources, going from 561 million pesos in 2007 to three billion pesos in 2013, with Guerrero, together with Oaxaca and Chiapas, as the states that year after year absorb more than 40 % of the total budget that is distributed beween 16 states of the Republic. Around 60 % of the public resources are destined to subsidizing up to 90 % of the value of the investments in infrastructure and equipment that productive projects require.

According to figures from UTN-FAO (2013), at the end of 2012, PESA had 295 thousand 162 valid projects3 distributed between 16 states, 40 % of which corresponded to the backyard production of eggs and poultry meat. In this regard, according to the same source, in the 2007-2012 period, approximately 117 thousand 500 projects were implemented for the production of eggs and poultry meat at the national level. Of this total, 24 % are located in Chiapas and 14 % in Guerrero.

For the case of Guerrero, up until 2011, at least one fourth of the projects implemented were directed at the production of eggs and poultry meat. And this is because, after maize and bean, these foods are the ones that families produce more in the marginalized regions of Guerrero (around 89 % produces these). However, between 50 and 60 % of the families manifest purchasing these foods during the whole year, which reflects the insufficiency of local production and suggests the need to improve the productive capacity of the backyard systems or else to incorporate new families into the production. In addition, it is important to consider that an increase in maize prices has negative impacts for the net grain purchasers (Levin and Vimefall, 2015), which is why these consumers are more vulnerable in the current scenarios of price volatility.

In this sense, the supports for raising animals have been quite utilized, since it is considered that small-scale livestock production represents an effective alternative to reach food security (FAO, 2011; FAO, 2013). For the poor rural population, farm animals constitute an important element of subsistence, since they perform multiple functions such as producing foods and fertilizers, generating income, as a source of traction, in addition to constituting a financial asset. In particular, small animals like poultry require a minimum investment by poor producers, they can be raised near the household, and they can be fed with “residues” from agricultural production (Reist et al., 2007).

In this context, the objective of this research was to analyze the situation of backyard poultry production projects implemented in the state of Guerrero after 18, 30 and 48 months of their implementation and the relation that they have with the family abilities and assets, with the aim of verifying the factors that determine their sustainability and formulating recommendations about the guidelines that a public policy should consider to foster the production of foods at the level of poor families in the rural environment.

Materials and methods

Study zone

The state of Guerrero is located in the south of the Mexican Republic. It is made up of seven economic regions with a variety of climates like warm sub-humid, semi-warm, temperate and temperate sub-humid. Of the population, 58 % is urban, 42 % rural, and 15 out of 100 people who are older than five years old are speakers of some indigenous language (INEGI, 2011).

After Chiapas, Guerrero is the state with the highest proportion of inhabitants under conditions of poverty (69.7 %) and extreme poverty (31.7 %) in all of México. By 2012, of the 3.5 million inhabitants in the state, 39.4 % showed scarcity over access to food (CONEVAL, 2013).

Sources of information and collection instruments

Between 2007 and 2009, 6,909 poultry production projects were supported with resources from PESA. Of the 2,268 that corresponded to the 2009 exercise, a random sample of 329 Family Poultry Production Units (UAPF) was selected, with 95 % reliability and 5 % precision, through sampling of proportions with maximum variance. From this sample only 107 projects had at least one year of having been implemented and they were the ones that the first survey was applied to in December 2010. In this first sample, 39 UAPFs were found with 18 months of operation and 68 others with 30 months.

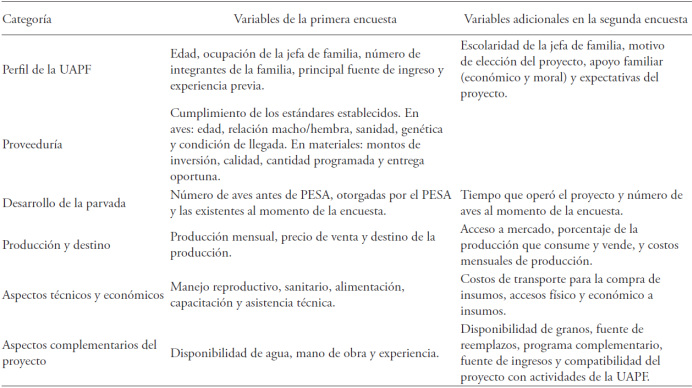

With the aim of following up on these UAPFs, in June 2012 a second questionnaire was applied to 51 units located in the localities and regions with highest number of poultry production projects from the original sample. Ten projects were found that had 36 months of operation and 41 with 48 months. The structure of the questionnaires applied is shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Structure of the questionnaires used to collect information.

Source: authors’ elaboration with elements from the surveys applied.

The availability of the grain was calculated as the percentage of requirements of the UAPF that could be supplied with the grain production by the family; therefore, it is zero for those who do not produce grain and depend totally on the purchase and 100 % for those who are self-sufficient throughout the year.

The qualitative variables were categorized with values of 0 and 1, forming two groups; group 1 for the UAPFs that presented the attribute of interest and 0 when it was another option.

Analysis of information

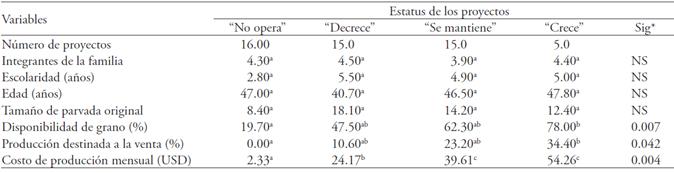

The UAPFs were grouped according to their statuses, which were defined by considering the percentage change of the initial flock (sum of the existing flock before PESA, plus the birds granted by the program) compared to the moment of application of the second survey (Table 2). In some analysis, the two first statuses were grouped as UAPFs with “undesirable” status, while the two remaining ones were grouped as UAPFs with “desirable” status.

For the comparative analysis of seasonal changes, statistical descriptors were used with the quantitative variables of study, while for the impact of each one of the variables on the status of the UAPFs, a variance analysis (VA) was performed, and later Scheffé tests for means comparison. The information of economic character was transformed into US Dollars, considering the average exchange rate during the period of execution of the projects (1 USD was equal to 12.06 Mexican pesos). SAS was used for the analysis (SAS, 2004).

Results and discussion

Profile of the families who operate the UAPFs

The families which participate in the program are made up of four members, whose head of household is 45 years old in average, 20 % of whom are younger than 30 years and 14 % older than 60. The average schooling is four years of effective study. Their predominant activity is agriculture and livestock production in 46 % of the cases. In the second place, there are families whose main source of income is workdays, representing 19 %.

Before the intervention by PESA, poultry production was an activity practiced by 89 % of the families, with an average of 13 Creole birds, but with broad variation, since 46 % had 10 or less and only 17 % had a flock of 25 or more birds. The production was directed fundamentally at auto-consumption and occasionally the excess was sold. Management of the birds was done under a traditional system with Creole birds, in the household’s courtyard and outdoors, which exposed the flock to predators. The diet was based on kitchen scraps, a situation similar to what was reported by Reist et al. (2007); also vegetables and insects that the birds collected on the field, without sanitary control, but without relevant problems of disease due to the resistance and adaptation of the birds to the local conditions.

A production system of these characteristics does not demand much time and work from the family, or significant monetary disbursements, since it is developed with materials and inputs available in the locality, taking advantage of the work of women and children. Bird breeding was performed with the aim of obtaining eggs to be incubated, for consumption and occasionally for their sale.

This production system is common in marginalized rural regions of the world, where family poultry production also does not represent an important source of income. The broad diffusion of the system is due to its low cost and small demands in management, its low contribution to the income is the result of not having important scales of production, for in general the families have less than 20 birds, which does not allow having production excesses to allocate to the market (Khieu, 1999; Kyvsgaard et al., 1999; Dolberg, 2003). In addition, limited productive parameters are achieved, such as periods of 180 to 210 days to begin egg-laying (Castañeda Naranjo, 2000; Centeno et al., 2007) and short productive cycles that barely allow obtaining between 60 and 65 eggs per year (Castañeda Naranjo, 2000; Mengesha, 2013).

The intervention approach by PESA

PESA public subsidies in Guerrero consisted in the delivery of materials for the construction of a gallery or henhouse made of sheet, mesh, concrete and cement blocks, as well as improved-breed birds for the production of egg and meat. The families contributed local materials for the construction and workforce. In contrast with other programs, the correct application and use of these resources is supervised in PESA by the ADRs. The intention was to significantly transform the production system, increasing its scale and improving the intensity. The program fixed the incentive of granting annual supports for poultry production or a different productive activity for the families that could maintain the projects in operation for three years, situation that was also supervised by the ADRs, but once the period concluded the supports would be stopped and the technical-operative accompaniment by the agencies interrupted.

This intervention is different from other international experiences, where the promotion of backyard poultry production rests in the provision of technical services, micro-financing, accessibility to medicine and vaccines, and only exceptionally, improved-breed birds are delivered to the families (Huq and Mallik, 1999; Kumtakar, 1999).

Supplying the birds was carried out by two companies, which, at the time of the delivery, did not have the sufficient production capacity and delivered birds that were even only one week old, when the age agreed upon and recommended to reduce risks of mortality was at least six weeks of age. This caused for families to have to wait up to seven months for the birds to begin laying eggs, which translated into a reduction of the original size of the flock from mortality and from difficulties to feed them with the resources available.

In the first survey, at least 40 % of the families reported having received sick birds, although the delivery of vaccinated birds was stipulated to prevent the most common diseases such as Newcastle and avian flu. This problem was also detected by Yúnez Naude and Taylor (2009), who in the results from their evaluation mention that in some localities the households received animals in bad conditions which died before providing any benefit to the families.

In addition, uneven flocks were delivered in terms of the male/female rate4, situation that could only be verified once the birds grew, since at the time of receiving them they were too young and it was not possible to differentiate them based on sex.

The average investment in the first year for each UAPF was 699.90 USD, of which 583.70 USD were allotted for infrastructure and 116.20 USD to acquire birds. Some families received subsidies for the same project in a second and up to a third year as long as they participated in the program, so the total amounts of government support could be higher. Each UAPF received 32 birds in average, although there was variation depending on the region of study; for example, in the Mountain the average flock was 20 birds, while in the Costa Chica the average was 45.

Evolution of the status of UAPFs

Figure 1 shows that the “undesirable” status of the UAPFs registered a growing trend from the very moment when the intervention begins. However, most of the projects stayed in operation during the first 30 months in face of the incentive of receiving more subsidies, but once the three years of support have been accumulated, the status of “not operating” shows a drastic increase in face of the certainty that there will be no more subsidies. Only those UAPFs which are truly attractive from the economic point of view, and which provide relevant benefits to the families “remain” and “grow”.

Source: authors’ elaboration from data collected on the field in 2010 and 2012.

Figure 1 Change in status of the UAPFs with operation time.

This situation was also analyzed by Martínez-González et al. (2013) in goat production units, and they found that facing the incentive of receiving infrastructure or animals anew, the families kept the goat flocks stable or slowly decreasing, despite operating with little or no economic benefit.

Explicative factors of the change in status of the UAPFs

In addition to external factors, such as the environmental conditions in each region, the intervention strategy by PESA and the quality of the supply of goods and services, there are internal factors in the UAPFs that also explain the statuses (Table 3). In this sense, the age and schooling of the head of the household, the number of family members and the size of the flock present before the intervention were not determinant of the status, while the grain availability and the percentage of production allotted to sales do explain the differences in statuses; this does not agree with Emaikwu et al. (2011), who reported that in Kaduna, Nigeria, variables such as experience and schooling are related directly with the size of the flock, while variables like age of the producers and size of the family were inversely related. Previously, Adebayo and Adeola (2005) had found that access to financing and level of schooling had a positive relation with poultry production, and that access to extension services was a limiting factor of production.

Table 3 Characteristics of the UAPFs and their relation with the status of poultry production projects in 2012.

Source: authors’ elaboration with field information 2012.

Sig*: Level of significance according to Scheffé’s test; NS: Non-significant at < 0.05 of probability.

For example, the “not operating” status presents average grain availability below 20 % of the annual requirements by the UAPFs, while the statuses “desirable” (“remains” and “grows”) have average grain availability above 60 %. This evidence suggests that in order to achieve satisfactory results in a strategy of promotion of family poultry production, it is essential to guarantee the grain availability above 60 % of the flock’s requirements, since when there is a reliance on purchasing food, it is unviable and unsustainable to produce egg and meat under backyard conditions, which agrees with other findings reported in various studies (Centeno et al., 2007; Morales, 2010; Zaragoza et al., 2011; Oladunni and Fatuase, 2014); also, they are more vulnerable when there is an increase in food prices (Dorward, 2013; Levin and Vimefall, 2015).

On the other hand, although in the PESA strategy poultry production claims to contribute to family self-sufficiency, the results suggest that the “desirable” statuses are associated to UAPFs that assign greater volumes of their production to selling. That is, the incentive of generating income is fundamental for the family for the projects to remain.

A third factor associated to this that influences the statuses in a determinant manner is the demand for liquid money to sustain the expenses for medicines and in particularly for bird food, in the case of not producing enough maize. Thus, the UAPFs with status “remain” demand in average 39.60 USD per month and this amount increases in those with “growing” status up to 54.30 USD, which explains the relevance of selling a part of the production.

It is at this level where families face the dilemma of guaranteeing the birds’ diet, allotting part of their meagre income in cash, or channeling the income available to support the family. Facing this dilemma, they generally opt for the second and attention towards the birds decreases or the project is abandoned because of the high cost of opportunity. In this regard Khieu (1999), estimates that providing balanced meals to a flock of between 10 and 15 birds per year could be equivalent to feeding a person for six months. This only considers the costs of feeding a flock, without including the possible benefits that could be obtained from producing meat and eggs to feed the family.

Effectivity of the intervention by PESA

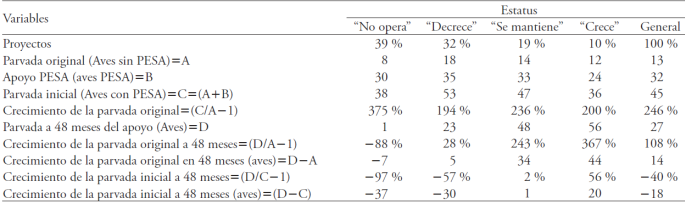

To estimate the effectiveness of the intervention, Table 4 shows the dynamics of the average flock for all the UAPFS and for the different statuses. The results obtained reveal that the average size of the existing flock at 48 months after the beginning of the PESA intervention was 108 % higher than the one without PESA. This suggests that it is possible to duplicate the productive capacity in eggs and poultry meat after four years of intervention in poor families, through a strategy of investment that considers the delivery of improved-breed birds, infrastructure for lodging and training.

Table 4 Dynamics of the average flock for the different statuses at 48 months since their implementation.

Source: authors’ elaboration with field information 2012.

However, when analyzing the dynamics of the flock taking into consideration the four statuses formed for this study, it is observed that this growth above 100 % from the original flock is shown by only 29 % of the families supported by the program, since the remaining 71 % of the UAPFs show a decrease in the flock with a clear tendency to disappear or else it had already disappeared completely 48 months after the PESA intervention began.

These findings suggest that an approach of massive promotion is not justified, and that better focalization of the intervention is needed, taking as priority those families that fulfill a profile that transcends simple eligibility criteria as families: “those who want”, which are in conditions of poverty, or which already have birds. The minimum desirable profile that families must fulfill to guarantee the effectiveness of a strategy for promotion of backyard poultry production would be: 1) to produce at least 60 % of the annual grain needs of the flock; 2) to have family support consisting in workforce and at least 40 USD per month for the purchase of inputs; and 3) have possibilities for the sale of part of the production, which implies producing above the requirements for auto-consumption and having conditions for access to local markets.

In addition to the waste of public resources, the lack of focalization translates into an even greater impoverishment of the families in terms of income, for they incur in higher production costs than the net benefits obtained or of the prices at which the same product could be purchased in the open market. This implies that when a public policy is directed at the poor, the issue of production should be considered, in addition to taking seriously into account the operative restrictions that families face to produce their own foods, and not only valuation criteria linked to the deficit in foods, patterns of food consumption, or the prior existence of some birds in the backyard. Failing to consider these types of findings contravenes the objective by which small-scale livestock production has been widely used, for as has been indicated (FAO, 2011; FAO 2013), these projects represent an option to reach food security.

In this regard, De Janvry and Sadoulet (2000) point out that, among the pathways to overcome rural poverty, agricultural and livestock production have viability only for those who have enough natural capital, and under market, institutional and policy contexts that allow the profitable use of this productive asset. On the other hand, Ashley and Carney (1999) mention that according to the experience generated by programs of productive promotion in Kenya, it is necessary to involve only the families interested and that have the necessary resource endowment for the projects and not all the families in conditions of poverty. Likewise, according to the South Asia Pro Poor Livestock Policy Programme, delivering improved-breed birds to families that live in marginalized zones is a good decision if what is sought is to increase the egg and meat production in a short time, but this pathway is not an option for most of the small-scale producers, when what is sought is to foster self-sustainable poultry production systems (SAPPLPP, 2010). That is, in order to be successful in the promotion of backyard poultry production projects; social, commercial, credit, and cultural factors should be considered, and naturally also technical aspects (Riise et al., 2005).

These recommendations and the findings of this study contrast with the conclusions from various evaluations practiced on PESA in Guerrero. In fact, Yúnez and Taylor (2009) point out that the population supported by PESA had a mean production, sale and auto-consumption of eggs higher than the families that were not supported by the program, and that the most consistent positive impact of PESA was the one that corresponds to the diet from consumption of poultry meat. In turn, Serna Hidalgo and Ordaz (2011) reported that the program increased the income of families supported by 14 % compared to those that were not beneficiaries of the program. On the other hand, Pastrana Peláez (2011) mentioned that around 42 % of the production units with operating projects manifested improvements in their food situation, in addition to receiving income from the sale of excess product.

What these evaluations overlook is that, although families supported by PESA could have registered higher production and income than the families that are not beneficiaries, this situation is only present in a third of the families, since in the rest the bird flock completely disappears or decreases drastically after 48 months of the intervention. Likewise, given that the prior evaluations were practiced at a time when the families were still in their first and second year of backing, of the three years considered, they had incentives to maintain the operation of the projects even when they were not sustainable.

In addition to this, Banerjee et al. (2015) conclude that it is possible to improve the income and welfare of poor families in a sustainable manner by using a multifaceted intervention approach. The authors systematize evidences from projects implemented in 10 495 households in six countries, where before the families received the support assets they had training and practice in technical (management, nutrition and health of the livestock) and administrative (business management) matters. In addition to the assets (primarily goats, chickens and sheep), they also received assistance in savings and credit schemes, as well as public health services for members of the family.

Conclusions

The “new normalcy” of volatile food prices affects poor families to a greater extent, since they assign nearly half their income to purchasing food. Therefore, in diverse developing countries public policies have been designed that tend to contribute to the food security of the poorest rural population. In the case of México, PESA has widely promoted backyard poultry production, but the results obtained in this study show that only the statuses with “desirable” dynamics would manage to produce these foods in a sustainable manner. This signals a poor performance in terms of contribution to the achievement of food security and an inefficient use of public resources.

The restrictions found for family poultry production in marginalized rural zones were grain availability, liquidity to purchase inputs, and access to local markets. Therefore, the issue of substance is that PESA must transcend the traditional vision that the provision of goods and services to specific segments of the population is enough to develop a productive activity like backyard poultry production, and it must consider the total of restrictions that limit the development of such an activity.

Indeed, the analysis of the restrictions must place the focus not only on the determinants of the abilities of rural households, which give viability to the productive activity that is being promoted (technical abilities and resource endowment, for example), but rather also to the equally determinant variables in decision making by rural families that do not depend on the productive activity (such as the opportunity cost of the family workforce or the life aspirations of its members).

This is particularly relevant because poverty and inequality are not only determined by access to goods and services, but also by the aspirations and the effective capacity of people to impact their reality with the aim of reaching the objectives and commitments that they consider important based on their values.

An aspect that was not considered but which is important to research to complete the analysis of restrictions is related to the role of agents with the ability to influence the political system, who promote a spoils system, bureaucratization, and the corruption of programs like PESA, since this is another factor that determines the possibilities of reaching the aspirations and effective capacity of rural poor families to impact their reality.

REFERENCES

Adebayo, O. O., and R. G. Adeola. 2005. Socio-Economic factors affecting poultry farmers in Ejigbo local government area of Osun state. Journal of Human Ecology, 18(1), 39-41. [ Links ]

Alvarado Bahena, Liliana. 2010. Mitos y verdades sobre el programa oportunidades: alternativas para el futuro. Avance-Análisis, Investigación y estudios para el desarrollo, A. C. Ethos Fundación. México, D. F. 119 p. [ Links ]

Ashley, Caroline, and Diana Carney. 1999. Sustainable livelihoods: Lessons from early experience. Department for International Development. London, UK. 55 p. [ Links ]

Banerjee, Abhijit, Esther Duflo, Nathanael Goldberg, Dean Karlan, Robert Osei, William Parienté, Jeremy Shapiro, Bram Thuysbaert, and Cristopher Udry. 2015. A multifaceted program causes lasting progress for the very poor: Evidence from six countries. Science. 348 (6236):1260799. DOI: 10.1126/science.1260799. [ Links ]

BID (Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo). 2008. Países necesitan invertir más para prevenir que la crisis alimentaria profundice la pobreza. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.iadb.org/es/noticias/articulos/2008-08-12/paises-necesitan-invertir-mas-para-prevenir-que-la-crisis-alimentaria-profundice-la-pobreza,4718.html Consultado el 15 de abril de 2014. [ Links ]

Castañeda Naranjo, Nora Elena. 2000. Capacitación en huerta familiar y especies menores, dirigida a mujeres campesinas del municipio de Pinillos. Cartilla cuatro. La gallina criolla. Ministerio de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural. Magangué Bolivar Colombia. 73 p. [ Links ]

Centeno Bautista, Sinaí Betzabé, Carlos Antonio López Díaz, y Marco Antonio Juárez Estrada. 2007. Producción avícola familiar en una comunidad del municipio de Ixtacamaxtitlán, Puebla. Téc. Pecu. Méx. 45(1):41-60. [ Links ]

CONEVAL (Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de desarrollo Social). 2011. Informe de evaluación de la política de desarrollo social en México 2011. México, D. F. 152 p. Disponible In: Disponible In: http://web.coneval.gob.mx/Informes/Evaluaci%C3%B3n%202011/Informe%20de%20Evaluaci%C3%B3n%20de%20la%20Pol%C3%ADtica%20de%20Desarrollo%20Social%20 2011/Informe_de_evaluacion_de_politica_social_2011.pdf Consultado el 10 de diciembre de 2013. [ Links ]

CONEVAL (Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de desarrollo Social). 2013. Informe de pobreza en México 2012. México, D. F. 123 p. Disponible In: Disponible In: http://www.coneval.gob.mx/Informes/Pobreza/Informe%20de%20Pobreza%20en%20Mexico%202012/Informe%20de%20pobreza%20en%20M%C3%A9xico%202012_131025.pdf Consultado el 15 de mayo de 2014. [ Links ]

De Janvry, Alain, and Elizabeth Sadoulet. 2000. Rural poverty in Latin America: determinants and exit paths. Food Policy. 25(4):389-409. [ Links ]

Dolberg, Frands. 2003. Review of household poultry production as a tool in poverty reduction with focus on Bangladesh and India. Pro-Poor Livestock Policy Initiative (PPLPI). Workimg Paper No. 6. Rome Italia. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/23762/1/wp030006.pdf . Consultado el 12 de enero de 2014 [ Links ]

Dorward, Andrew. 2013. Agricultural labour productivity, food prices and sustainable development impacts and indicators. Food Policy. 39:40-50 DOI:10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.12.003. [ Links ]

Emaikwu, K. K, D. O. Chikwendu, and A. S. Sani. 2011. Determinants of flock size in broiler production in Kaduna State of Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development. 3(11): 202-211. [ Links ]

FAO (Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación). 2011. World livestock 2011 - livestock in food security. Roma, Italia. In: In: http://www.fao.org/docrep/014/i2373e/i2373e.pdf Consultado el 10 de mayo de 2014. 151 p. [ Links ]

FAO (Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación). 2013. El estado mundial de la agricultura y la alimentación 2013. Sistemas alimentarios para alcanzar una mejor nutrición. Roma, Italia. In: In: http://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3300s/i3300s.pdf . Consultado el 5 de mayo de 2014. 109 p. [ Links ]

FAO (Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación). 2014. Panorama de la seguridad alimentaria y nutricional en América Latina y el Caribe 2013. Hambre en América Latina y el Caribe: acercándose a los objetivos del milenio. In: In: http://www.fao.org/docrep/019/i3520s/i3520s.pdf Consultado el 20 de mayo de 2014. 56 p. [ Links ]

Gobierno de México. 2010. Reglas de operación de los programas de la Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación. Diario Oficial de la Federación México, 31 de diciembre de 2010, quinta y sexta sección. México, D.F. pp: 1- 244. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez, J. P., J. Rivera-Dommarco, T. Shamah-Levy, S. Villalpando-Hernández, A. Franco, L. Cuevas-Nasu, M. Romero-Martínez, y M. Hernández-Ávila. 2013. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2012. Resultados nacionales. 2a. ed. Cuernavaca, México: Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública. In: In: http://ensanut.insp.mx/informes/ENSANUT2012ResultadosNacionales2Ed.pdf . Consultado el 20 de abril de 2014. 190 p. [ Links ]

Huq, Fazlul, and Kabir Mallik. 1999. The Role of Women in Poultry Development: Proshika Experiences. Dhaka, Bangladesh. In: In: http://www.fao.org/docrep/004/ac154e/AC154E04.htm Consultado el 10 de febrero de 2014. [ Links ]

INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). 2011. Cuéntame. Información por entidad, estado de Guerrero. Disponible In: Disponible In: http://cuentame.inegi.org.mx/monografias/informacion/gro/default.aspx?tema=me&e=12 Consultado el 22 de febrero de 2014. [ Links ]

Khieu, Borin. 1999. Chicken Production, Food Security and Renovative Extension Methodology in the SPFS Cambodia. University of Tropical Agriculture Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Royal University of Agriculture. Kingdom of Cambodia. In: In: http://www.fao.org/docrep/004/ac154e/AC154E09.htm Consultado el 30 de abril de 2014. [ Links ]

Kumtakar, Prema. 1999. Scope for Backyard Poultry (BYP) Development under the Special Training Program of the Madhya Pradesh Women in Agriculture (MAPWA) Project. Madhya Pradesh, India. In: In: http://www.fao.org/docrep/004/ac154e/AC154E04.htm#ch3.1 Consultado el 10 de abril de 2014. [ Links ]

Kyvsgaard, Niels Chr., Luz Adilia Luna, and Peter Nansen. 1999. Analysis of a Traditional Grain and Scavenge-Based Poultry System in Nicaragua. In: In: http://www.fao.org/docrep/004/ac154e/AC154E04.htm Consultado el 19 de mayo de 2014. [ Links ]

Levin, Jörgen, and Elin Vimefall. 2015. Welfare impact of higher maize prices when allowing for heterogeneous price increases. Food Policy. 57:1-12. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2015.08.004. [ Links ]

Levy, Santiago, y Evelyne Rodríguez. 2005. Sin herencia de pobreza. El programa Progresa - Oportunidades de México. Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo. Editorial Planeta; México, D. F. 236 p. [ Links ]

Martínez-González, Enrique G., Manrrubio Muñoz-Rodríguez, Vinicio H. Santoyo-Cortés, Dolores Gómez-Pérez, y J. Reyes Altamirano-Cárdenas. 2013. Lecciones de la promoción de proyectos caprinos a través del Programa Estratégico de Seguridad Alimentaria en Guerrero, México. Agricultura, Sociedad y Desarrollo. 10(2): 177-193. [ Links ]

Mayer-Foulkes, David, y Carlos Larrea. 2007. Racial and Ethnic Health Inequities: Bolivia, Brazil, Guatemala, and Peru. Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económica, Ciudad de México. In: In: http://www.cide.edu/investigador/documentos/david.mayer/RacialInequitiesMayerLarrea5.pdf Consultado el 20 de febrero de 2014. 42 p. [ Links ]

Mengesha, Mammo. 2013. Biophysical and the socio-economics of chicken production. African Journal of Agricultural Research. 8 (18):1828-1836. DOI: 10.5897/AJAR11.1746. [ Links ]

Morales Florián, Heilhard Alain. 2010. Estudio comparativo del estado de viabilidad de la pequeña avicultura en cuatro micro regiones de Colombia. Tesis de maestría. Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Bogotá Colombia. 112 p. [ Links ]

OCDE/FAO (Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos/ Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación). 2013. Perspectivas agrícolas 2013-2022. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Texcoco, Estado de México. 338 p. DOI: 10.1787/agr_outlook-2013-es. [ Links ]

Oladunni, F. E., and A. I. Fatuase. 2014. Economic analysis of backyard poultry farming in Akoko North West local government area of Ondo State, Nigeria. Global Journal of Biology, Agriculture & Health Sciences. 3(1):141-147. [ Links ]

Pastrana Peláez, Sergio Alejandro. 2011. Informe de evaluación de la sustentabilidad de las Unidades de Producción Familiar del PESA. Guerrero, México. 77 p. Disponible In: Disponible In: http://www.sagarpa.gob.mx/Delegaciones/guerrero/Documents/Comit%C3%A9%20T%C3%A9cnico%20Estatal%20de%20Evaluaci%C3%B3n/Evaluaci%C3%B3n%202011/INFORME%20PESA.pdf Consultado el 5 de enero de 2014. [ Links ]

Reist, Sabine, Felix Hintermann, and Rosmarie Sommer. 2007. La revolución ganadera: ¿Una oportunidad para los productores pobres? Zollikofen, Suiza. Agencia Suiza para el Desarrollo y la Cooperación. InfoResources Focus no. 1/07. In: In: http://www.inforesources.ch/pdf/focus07_1_s.pdf Consultado el 10 de febrero de 2014. 16 p. [ Links ]

Riise, J. C., A. Permin, and K. N. Kryger. 2005. Strategies for developing family poultry production at village level - Experiences from West Africa and Asia. World’s Poultry Science Journal. 61 (March):15-22. DOI: 10.1079/WPS200437. [ Links ]

SAPPLPP (South Asia Pro Poor Livestock Policy Programme). 2010. Small-scale poultry farming and poverty reduction in South Asia. From good practices to good policies in Bangladesh, Bhutan and India. In: In: http://sapplpp.org/lessonslearnt/small-holder-poultry/smallscale-poultry-farming-and-poverty-reduction-in-southasia#.U4Sbv_l5OkE Consultado el 13 de octubre de 2013. 46 p. [ Links ]

SAS (Statistical Analysis System Inst. Inc.). 2004. SAS/STAT® User’s Guide: Statistics; Version 9.1. Cary; NC, USA. pp: 1 - 480. [ Links ]

SEDESOL (Secretaría de Desarrollo Social). 2012. Oportunidades, 15 años de resultados. Programa de Desarrollo Humano Oportunidades. México, D. F. Disponible In: Disponible In: http://www.oportunidades.gob.mx/Portal/work/sites/Web/resources/ArchivoContent/2107/BAJA%20Oportunidades%2015%20anos%20de%20resultados.pdf Consultado el 20 de mayo de 2014. 54 p. [ Links ]

Serna Hidalgo, Braulio, y Juan Luis Ordaz. 2011. Evaluación del proyecto estratégico para la seguridad alimentaria Guerrero sin hambre (PESA-GSH). Evaluación de impacto. Volumen I. Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe. Naciones Unidas, México. Distrito Federal, México. 81 p. [ Links ]

UTN-FAO (Unidad Técnica Nacional - Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación). 2013. Producción de carne de ave y huevo de traspatio en el PESA. Ponencia presentada en el tercer foro internacional sobre ga nadería de traspatio y seguridad alimentaria, realizado del 29 al 31 de octubre del 2012, en Veracruz, México. Colegio de Postgraduados- Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. [ Links ]

Yúnez Naude, Antonio, y J. Edward Taylor. 2009. Evaluación externa del Programa de Atención a Productores de Menores Ingresos (PAPMI/Guerrero sin Hambre). Colegio de México. Programa de Estudios del Cambio Económico y la Sustenta bilidad del Agro Mexicano. Distrito Federal, México. 78. [ Links ]

Zaragoza, L., B. Martínez, A. Méndez, V. Rodríguez, J. S. Hernández, G. Rodríguez, y R. Perezgrovas. 2011. Avicultura familiar en comunidades indígenas de Chiapas, México. Actas Iberoamericanas de Conservación Animal. 1:411-415. [ Links ]

1According to Gutiérrez et al. (2013), 40 % of the Mexican households receive at least one program for dietary support, with Oportunidades being the one with greatest coverage, reaching 18.8 % of the population, mostly rural, since for each family that receives the support from this program in urban zones, five receive it in rural areas. Because poverty is concentrated in marginalized rural zones, seven out of 10 beneficiaries of Oportunidades live in localities of under 2500 inhabitants, many of them indigenous (SEDESOL, 2012).

2A Rural Development Agency (Agencias de Desarrollo Rural, ADR) is a private organization made up of a base nucleus of professionals, mostly agronomists and veterinaries, who are hired by the government to identify, formulate, manage, implement and follow-up family projects. This organization receives technical and methodological training by FAO.

3“Current Project” refers to the productive projects that at the end of 2012 still had technical accompaniment by the ADRs.

Received: June 2014; Accepted: December 2015

text in

text in