Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

Share

Revista mexicana de biodiversidad

On-line version ISSN 2007-8706Print version ISSN 1870-3453

Rev. Mex. Biodiv. vol.83 n.2 México Jun. 2012

Manejo y aprovechamiento

Knowledge of the Yucatec Maya in seasonal tropical forest management: the forage plants

El conocimiento de los mayas yucatecos en el manejo del bosque tropical estacional: las plantas forrajeras

José Salvador Flores1 and Francisco Bautista2*

1 Departamento de Botánica, Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, Campus de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias, km 15.5 Carretera Mérida– Xmatkuil, 97000 Mérida, Yucatán, México.

2 Centro de Investigaciones en Geografía Ambiental, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Antigua Carretera a Pátzcuaro No. 8701, Col. Ex–Hacienda de San José de La Huerta, 58190 Morelia, Michoacán, México. *leptosol@ciga.unam.mx.

Recibido: 06 mayo 2011

Aceptado: 07 febrero 2012

Abstract

Indigenous knowledge and the millenary experience in management of natural vegetation on karstic landscapes are important aspects that should be considered in animal production in seasonal tropical environments. The aim of the present work was to make an inventory of native plants associated to soilscapes from seasonal tropical forests from the Yucatán Peninsula that are used as forage by Mayan people. The work was carried out in 27 Mayan communities on karst landscapes in the Yucatán Peninsula as a part of the "Ethnoflora Yucatanense" project of the Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán. Samples were taken of forage plants together with corresponding floristic and ethnobotanical information. Data were processed in EXCEL dynamic tables, grouped by plant family, geoforms and soils, life form and animal consumers. Results indicate that Mayan communities use 196 plant species as forage: 139 herbaceous, 17 shrubs, 35 trees and 2 palms. These plants are fed to cows, pigs, horses, lambs, turkeys, chickens, ducks and pigeons. The use of native forage plants may be an agricultural option both for rural communities and for intensive animal production on silvopastoral systems on karstic tropical landscapes from the Yucatán Peninsula.

Key words: forage trees, Maya culture, animal production, edible plants, legumes, tropical karst.

Resumen

El conocimiento indígena y la experiencia de milenios de años en el manejo de la vegetación natural en ambientes kársticos tropicales son aspectos importantes que deben ser considerados en la producción animal. El objetivo de este trabajo fue hacer un inventario de las plantas forrajeras nativas de los bosques tropicales estacionales de la península de Yucatán que son utilizadas por los mayas, incluyendo los paisajes edáficos en los que se encuentran las plantas, información que servirá de base para la planeación de las actividades agropecuarias. El trabajo se llevó al cabo en 27 comunidades indígenas mayas, como parte del proyecto "Etnoflora Yucatanense" de la Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán. Las muestras de plantas forrajeras se tomaron con información florística y etnobotánica. Los datos se manejaron mediante tablas dinámicas en Excel y fueron agrupados por familia florística, geoforma, forma de vida y por los animales que las consumen. Las comunidades mayas utilizan 196 especies de plantas para alimentar a los animales: 139 herbáceas, 17 arbustos, 35 árboles y dos palmeras. Las plantas forrajeras nativas son utilizadas para alimentar vacas, cerdos, caballos, corderos, pavos, pollos, patos y palomas. Las plantas forrajeras nativas pueden ser una opción de mejoramiento de la agricultura de temporal y también para la producción animal intensiva en sistemas silvopastoriles en los paisajes kársticos tropicales de la península de Yucatán.

Palabras clave: árboles forrajeros, cultura maya, producción animal, plantas comestibles, leguminosas, karst tropical.

Introduction

Mayan people have used their natural resources since the Preclassic period (approximately, between 2 000, some authors considering it could be 3 000, to 1 000 years B.C.) (Vargas, 2004). While studies about the Maya knowledge of plants (Barrera et al., 1976; Sosa et al., 1985; Flores et al., 2001; Arellano et al., 2003) and soils have been published (Bautista et al., 2003a; Bautista et al., 2005; Bautista and Zinck, 2010), studies made about forage plants are mainly focused on their chemical composition, animal consumption and plant productivity (Vargas et al., 1987; Mizrahi et al., 1998; Sosa et al., 2000; Solorio and Solorio, 2002; Sandoval et al., 2005; Zapata et al., 2009), without consideration of soils, geomorphic environments, geoforms and spatial aspects. For this reason, the Maya culture and its millenary knowledge provide an opportunity for studying the forage plants from seasonal tropical forest of karstic landscapes.

On the other hand, extensive cattle rising activities have been responsible for a large part of the deforestation of tropical and subtropical zones because of the conversion of forests in artificial grasslands. The gradual transformation of forests to pastures and agricultural lands has had negative ecological impacts, disturbing the functions of the karstic ecosystems, as well as altering and fragmenting the natural ecosystems (Harvey, 2001).

The expansion of pastures and the conservation of ecosystems are 2 incentives for the search of new forms of production in tropical karstic zones (Zapata et al., 2009; Castillo et al., 2010). Silvopastoral systems using wild plants are characterized by their biodiversity and by their amply demonstrated economic and environmental benefits, providing a possibility to improve the productivity and stability of land use systems (Giraldo et al., 1995; Solorio y Solorio, 2002; Llamas et al., 2004; Zapata et al., 2009). However, their establishment depends on availability of local knowledge and management of soils and plants, due to the fact that when exotic plants are used without any consideration for soils, the possibility of failure is increased.

Legume fodder trees are often planted, both within extensive grazing systems and in association with crops. However, the adoption of new agricultural systems has been slow because of the high costs of tree planting and management. Leptosols, Cambisols, Luvisols and Vertisols are the dominant soil groups in karstic areas, characterized by very fragmented soil–relief patterns and high spatial soil heterogeneity (Bautista et al., 2004b; Bautista et al., 2005; Bautista et al., 2011). In karstic areas with seasonal tropical climate, studies carried out on the identification of new forage plants other than grasses are commonly scarce, but highly relevant (Sosa et al., 2000), which makes it difficult to formulate appropriate planning strategies for agriculture, animal production and environmental preservation (NAS, 1979; NRC, 1989; Acosta et al., 1998; Flores, 2001; Flores, 2002).

The aim of the present work was to do an inventory of forage plants used by Mayan people from soilscapes in the Yucatán Peninsula, which could be used for designing silvopastoral systems for the karstic tropical zones.

Materials and methods

Study area. The Yucatán Peninsula is located in southeastern Mexico between 18° and 21°30' of northern latitude. It is a region of low relief with elevations generally being below 50 m a.s.l. (Bautista et al., 2005). The highest areas lay in the center of the peninsula, the elevation decreasing eastward and westward from there abruptly. The higher elevations correspond to the Ticul and Sayil hills located in the southern part of the state of Yucatán, with altitudes up to 250 m a.s.l. Four geomorphic environments with their respective soilscapes have been recognized in the Yucatán Peninsula, i.e. karstic (Leptosols, Cambisols, Luvisols, Vertisols), coastal (Arenosol, Regosols, Solonchacks, Histosols), fluvio–paludal (Gleysols, Solonchacks, Histosols), and tectono–karstic (Leptosols, Cambisols, Luvisols, Vertisols) with plains and hills as main geoforms (Bautista et al., 2011). The karstic environment can be subdivided in incipient, juvenile, mature with good drainage and mature with poor drainage. The northern coast is the driest area of the Yucatán Peninsula, with semi–arid climate of the subtypes BS1(h')w and BS0(h')w. On the island of Cozumel, the climate is of the warm humid subtype Am(f) with abundant winter rainfall. The rest of the Yucatán Peninsula has a warm subhumid climate with 3 subtypes of increasing moisture: Aw0, Aw1 and Aw2. The driest areas are located in the west and the wetter areas in the east (García, 2004). Forest cover includes various types from tropical deciduous forest to tropical evergreen forest. In coastal and other low–lying areas, vegetation includes savannah, petenes (i.e. tropical forests on residual hills), mangroves, coastal dune scrub, sedge, cattail marshes and tular (Flores and Espejel, 1994).

In the Yucatán Peninsula there are 3 large areas dedicated to cattle raising; 1), the eastern part of the state of Yucatán, with Leptosols having problems of effective depth, fertility, proliferation of weeds, besides the erratic midsummer rains (Bautista et al., 2011); 2), the southwestern part of the state of Campeche, with Leptosols, Vertisols and Gleysols presenting serious problems of internal drainage, and 3), the southwestern part of the state of Quintana Roo, with Leptosols, Gleysols and Vertisols with heavy soils with poor drainage. In these regions, the cattle density varies from 0.5 to 0.8 animals per hectare (Bautista et al., 2003b).

Plant collection and data management. During the 1989–1999 period, 20 interviews were carried out in each of the 27 studied Mayan communities as a part of the "Ethnoflora Yucatanense Project" (EYP) of the Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán (UADY). Samples of forage plants were collected together with associated floristic and ethnobotanical information. Based on a survey designed within the EYP, it was possible to explore several information entries (data fields) on the use of the plants (life cycle, life form and reproduction, parts used, forms of use and handling), as well as information on the interviewees and their economic activities. Each record contained the following fields: common names (Mayan and common Castilian name), types of use (35 fields), potential uses, part used (14 fields), in the case of being of alimentary use for humans and animals the form of preparation is described (16 fields), evaluation of the information (4 fields), form of reproduction (5 fields), flowering period (6 fields), period of leaf fall (6 fields), management degree (6 fields), management type (7 fields), source of material (11 fields), type of information source (9 fields), locality, municipality, state, interviewer, collection date and general observations (BADEPY–INIREB, 1985).

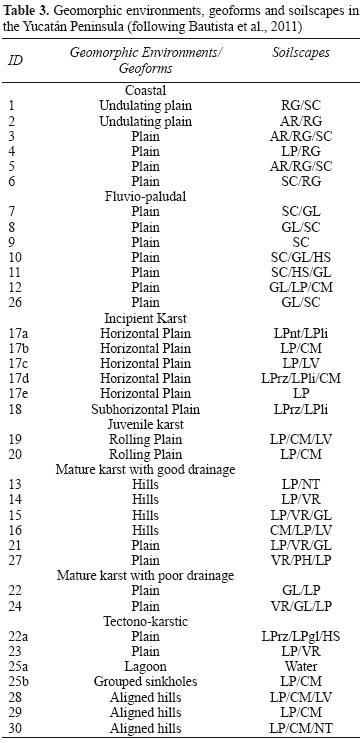

The information is completed with plant family, scientific name, life form (3 fields), the animal that consumes it (6 fields), geoforms and soilscapes in which the plant is located (Fig. 1) (Bautista et al., 2003b; Bautista et al., 2011), in accordance with the community in which the interview was carried out.

All the plants were collected during the 1989–1999 time period and were deposited in the herbarium of the Campus of Biological and Agricultural Sciences of the UADY. The botanical information was included in the "Ethnobotanical database of the Yucatán Peninsula" (BADEPY).

In addition, a bibliographic review was made in relation to the forage quality of native plants.

All plants were geographically located in the geomorphic environments, geoforms and soilscapes in which they were collected. Data on the scientific and Maya plant names, edible parts, life forms and consumption by domestic animals were managed in dynamic tables in EXCEL. Plant records may be grouped according to family, life form, geomorphic environment, geoforms, soilscapes or by animals consumption.

Results

A total of 196 plant species used as forage in the Yucatán Peninsula were detected, the families Fabaceae and Poaceae being the most represented (74 and 29 species respectively), followed by Convolvulaceae (8), Solanaceae (7), Asteraceae (6), Malphighiaceae (6), Malvaceae (6), Nyctaginaceae (5), Verbenaceae (5), Amaranthaceae (5) and other families with less than 5 species each (Fig. 2, Appendix 1).

The more widely distributed forage plants are: Amaranthus spinosus L., Carica papaya L., Viguiera dentata (Cav). Sprengel var. helianthoides (Kunth) Blake, Eleusine indica (L.) Gaertn, Panicum maximum Jacq., Paspalum notatum Alain ex Flügge., Leptochloa virgata (L.) P. Beauv., Celosia virgata Jacq., Olyra yucatana Chase, Acacia pennatula (Schltdl. and Cham.) Benth., Acacia riparia Kunth and Centrosema virginianum (L.) Benth. (Table 1).

From the total 196 species of fodder plants recorded, 140 (71%) are herbs, 19 (10%) shrubs, 35 (18%) trees and 2 (1%) are palms (Fig. 2). This fact is important since 73% of the species are herbaceous and therefore, of rapid growth (annual). Herbaceous forage plants have potential use in silvopastoral systems, more so considering that the majority belong to the legume family (Fabaceae).

The stem, leaves, buds and flowers of the arborescent and shrubby forage species have a potential as animal food sources. Moreover, 33 of these perennial plant species are multipurpose trees having uses such as wood, firewood, shade, live fences, medicinal, etc.

The comparison of our results with data from 3 cattle zones of the Yucatán Peninsula showed that in the latter only 7 species of African grasses are used as forage plants: Cynodon nlemfuensis (African bermudagrass), Hyparrhenia rufa (jaragua grass), Panicum maximun (Guinea grass), Pennisetum ciliare (buffelgrass), Pennisetum purpureum (elephant grass), Sorghum halepense (Jhonson grass), Stenotaphrum secundatum (St. Agustin grass). These plants represent only 3.6% of the total of forage plants recorded in the present study, while a great diversity of forage plants are used in the raising of backyard animals, especially in the north of the Yucatán Peninsula including part of the sisal, fruit tree and milpera zones (Barrera et al., 1976; Sánchez, 1993; Acosta et al., 1998; Flores, 2001; Flores, 2002).

Forage species used by Mayan communities. In the production of bovines, 25 arboreal species and 10 species of shrubs and 1 palm (Sabal mexicana) were found to have a potential for use in silvopastoral systems. Forage tree species are: Carica papaya, Pithecellobium dulce, Acacia gaumeri, Piscidia piscipula, Lysiloma latisiliquum, Acacia pennatula, Sesbania grandiflora, Brosimum alicastrum, Bursera simaruba, Colubrina arborescens, Leucaena leucocephala, Lonchocarpus guatemalensis, Diphysa carthagenensis, Ficus cotinifolia, Guazuma ulmifolia, Lonchocarpus hondurensis, Vitex gaumeri, Lonchocarpus yucatanensis, Byrsonima bucidaefolia, Colubrina greggii, Duranta repens, Jacaratia mexicana, Swartzia cubensis, Lonchocarpus rugosus and Pithecellobium saman. Forage shrub species are: Acacia riparia, Dalbergia glabra, Tithonia diversifolia, Acacia collinsii, Bunchosia glandulosa, Malpighia punicifolia, Neomillspaughia emarginata, Senna undulada, Tithonia rotundifolia and Calliandra houstoniana. Plants with a wider distribution are shown in figure 3. The chemical quality reported for some forage plants is presented in table 2.

The arboreal species with potential use as forage for porcine livestock are: Bursera simaruba, Leucaena leucocephala, Enterolobium cyclocarpum, Byrsonima crassifolia, Ficus yucatanenses, Psidium guajava, Simarouba glauca, Byrsonima bucidaefolia, Jacaratia mexicana, Swartzia cubensis, Ziziphus yucatanensis, Artocarpus communis and Pithecellobium saman. In addition, Bursera simaruba presents high ecological importance values in 12 and 26 year old fallows. Forage shrub species are: Bauhinia divaricada, Sesbania emerus, Piper auritum, Bunchosia glandulosa, Malpighia lundellii and Malpighia glabra. Bauhinia divaricata, Bunchosia glandulosa, Sesbania emerus and Piper auritum are woody forage plants consumed by pigs (Fig. 4).

Mayan knowledge includes 29 species of herbaceous and woody forage plants consumed by goats, of these species, those having a wider distribution (5 soilscapes o more) are: Acacia gaumeri, Leptochloa virgata, Olyra yucatana, Panicum maximum, Acacia riparia, Lasiacis divaricata, Gouinia guatemalensis, Panicum hirsutum, Wissadula amplissima, Gayoides crispa and Leucaena leucocephala. The preference displayed by goats for consumption of tree species is in the following order: Brosimum alicastrum> Lysiloma latisiliquum> Piscidia piscipula> Acacia pennatula (Alonso–Díaz et al., 2008).

The 5 most important plants used by the Maya communities for domestic animal consumption were: Carica papaya, Chloris virgata, Leptochloa virgata, Olyra yucatana, Desmodium procumbens, Rhynchosia yucatanensis and Byrsonima bucidaefolia with presence on 21, 9, 9, 9, 3, 2, and 2 soilscapes respectively.

The most important plants used by the Mayan people to feed rabbits are: Paspalum vaginatum, Boerhavia caribaea, Chaetocalyx scandens, Cracca greenmanii, Cracca panamensis and Crotalaria cajanifolia.

One hundred and twenty–seven species of plants were reported as appropriate for feeding equines, of these, the most widely distributed in the studied soilscapes are: Carica papaya, Pithecellobium dulce, Celosia virgata, Lysiloma latisiliquum, Piscidia piscipula, Chloris virgata, Leptochloa virgata, Olyra yucatana, Panicum maximum, Acacia riparia, Viguiera dentate, Eleusine indica, Lasiacis divaricata, Amaranthus dubius, Gouinia guatemalensis, Panicum hirsutum, Paspalum vaginatum, Senna occidentalis, Sida acuta, Sorghum halepense, Wissadula amplissima, Sesbania grandiflora, Brachiaria fasciculata, Gayoides crispa, Waltheria americana, Ximenia americana, Zea mays, Dalbergia glabra, Brosimum alicastrum, Bursera simaruba, Colubrina arborescens and Lonchocarpus guatemalensis (5 o more soilscapes)

The Mayan people use 39 forest plants for feeding poultry, of these, those found in 5 or more soilscapes studied are: Acacia gaumeri,Celosia virgata, Paspalum notatum, Amaranthus spinosus, Eleusine indica, Lasiacis divaricata, Amaranthus dubius, Hyptis suaveolens, Sida acuta, Amaranthus hybridus, Brachiaria fasciculata, Zea mays and Leucaena leucocephala.

Discussion

Arellano et al. (2003) estimated that the flora of the Yucatán Peninsula includes 2 200 species, based on that number, 8.6% of the flora is used by Mayan communities as forage, largely for feeding backyard animals including equine, bovine and porcine livestock and poultry.

Some authors such as Standley (1930), Sousa and Cabrera (1983) and Sosa et al. (1985) consider the Fabaceae to be the family having the most abundant number of species in the flora of the Yucatán Peninsula. It is noteworthy that legumes are amply recognized as being important forages for use to improve animal production (NAS, 1979; NRC, 1989).

López et al. (2008) found that some species such as Galactia multiflora, Psychotria nervosa, Macroptilium atropurpureum, Acalypha villosa, Cecropia obstusifolia, Piscidia piscipula, Trophis racemosa, Chaetocalyx scandens, Dalbergia glabra, Guazuma ulmifolia, Spondias mombin and Ampelocissus erdvendbergiana have potential as protein sources in tropical ruminant diets; however, these plants also have antinutritional compounds such as phenols. Currently, Mayan people use the non–legume species Brosimum alicastrum and Guazuma ulmifolia as forage sources for bovines (Sosa et al., 2004). Local producers in the study zone consider Bursera simaruba, Sesbania grandiflora, Lonchocarpus guatemalensis, Acacia pennatula, Lysiloma latisiliquum, Gliricidia sepium and Acacia gaumeri to be good quality forage plants (Ayala and Sandoval, 1995; Mizrahi et al., 1998; Solorio and Solorio, 2002; Llamas et al., 2004). In particular, Bauhinia divaricata and B. glandulosa are present in the natural vegetation in 12–year–old fallows, where they have high ecological importance values (Mizrahi et al., 1998). Bauhinia divaricata has the potential to be used in silvopastoral systems in seasonal tropical forests due to its coppicing capacity after pruning, thus forage can be produced during the dry season (Zapata et al., 2009). The recent karstic plain (ID 17) is dominated by Nudilithic Leptosols, Lithic Leptosols and Hyperskelethic Leptosols having low effective depth, low retention of humidity and a scarce amount of fine earth (Table 3). Leptosols present extreme restrictions for plant growth (Bautista et al., 2003a,b; Bautista et al., 2011), however, most of the recorded forage species (140 plants) are present in this karstic plain with Leptosols, which constitutes an opportunity for the design of silvopastoral systems under these particularly unfavorable conditions.

Goats select the quality of the forage they eat, preferentially consuming plants with the highest in vitro apparent dry matter (DM), digestibility (IVDMD) and in vitro gas production (IVGP) (Alonso–Díaz et al., 2008). However, further studies are required in order to evaluate the quality of the remaining 56 plants.

Considering that the state of Yucatán is the fourth largest pork producer in the country, and given the local relevance of the meat, the results of the present work could be used for the elaboration of nutritional supplements, thus diminishing the import of forage, principally by the use of Bursera simaruba, Jacaratia mexicana, Swartzia cubensis, Bunchosia glandulosa, Sesbania emerus and Piper auritum.

A large amount of herbaceous plant species is used for feeding livestock and poultry in the Mayan communities, which constitutes another opportunity for further research on the chemical, physical and biological characteristics of these plants, as well as their agronomic properties and their assimilation by animals. Also, since most herbaceous plants grow during the rainy season when forage is abundant, future studies must be focused on the conservation of the forage quality of these species in order to used during the dry season.

On the other hand, in the Yucatán Peninsula soils are highly heterogeneous, Leptosols, Cambisols, Luvisols, Vertisols and Gleysols being distributed in patches (Table 4) (Bautista et al., 2005; Zapata et al., 2009; Bautista et al., 2011). Therefore it is important to know soil distribution in order to design agricultural management practices that are appropriate for each soilscape for forage plants.

The design of silvopastoral systems considering forest management will allow for reducing tree establishment costs while also achieving meat and milk production from the beginning and in a continuous way.

The knowledge of Mayan people should be considered in the design of new agricultural programs of the region, especially in the cattle area. However, knowledge of the Mayan communities about the use of seasonal tropical forest plants as forage sources generates new research questions: What is the chemical quality of plants? What might be the problems generated by antinutritional compounds? What plants respond best to pruning? How does the quality and quantity of fodder vary in response to soil and climatic factors?

The present study is an example of the inclusion of the knowledge (corpus and praxis) of the Mayan people for the generation of natural resource productive strategies as new silvopastoral systems. However, to achieve sustainability goals it is also necessary to include the Maya cosmovision (kosmos), i.e., the respect for nature, and the concept that land occupants are not the "real" landowners.

The results of the present study allow for concluding that on the karstic tropical landscapes of the Yucatán Peninsula the Mayan people manage 196 forage plants, mostly from the Fabaceae and Poaceae families.

Mayan traditional knowledge on forage plants includes the edible parts and the consumption by domestic animals. This knowledge can be used to improve animal production systems. In this study we include geographic location, geomorphic environment, geoforms and soilscapes of the fodder plants.

Knowledge of the Mayan people about the use of tropical seasonal forest forage plant species provides us with valuable information that could be used to improve existing forms of livestock and poultry production, as well as the design of new practices suited for particular combinations of landscape components (e.g., relief, aquifers, soils and climate), such as those present in the karstic soilscapes of the Yucatán Peninsula.

Acknowledgements

The National Council for Science and Technology (CONACYT) supported the present research (Projects 0308P–B9506; R31624–B, 54–2003–2). The authors would like to thank Dra. Carmen Delgado–Carranza and the two anonymous referees for the important comments on the manuscript.

Literature cited

Acosta, B. L., J. S. Flores and A. Gómez–Pompa. 1998. Uso y manejo de plantas forrajeras para la cría de animales dentro del solar en una comunidad maya en Yucatán. Fascículo No. 14. Etnoflora Yucatanense. Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia. UADY. Yucatán, México. 128 p. [ Links ]

Aguilera, N. 1963. Los recursos naturales del sureste y su aprovechamiento: suelos. Revista de la Escuela Nacional de Agricultura Chapingo. 3 (Suppl 11–12):1–54. [ Links ]

Alonso–Díaz, M. A., J. F. J. Torres–Acosta, C. A. Sandoval, H. Hostec, A. J. Aguilar–Caballero, C. and M. Capetillo–Leal. 2008. Is goats' preference of forage trees affected by their tannin or fiber content when offered in cafeteria experiments? Animal Feed Science and Technology 141:36–48. [ Links ]

Alonso–Díaz, M. A., J. F. J. Torres–Acosta, C. A. Sandoval, H. Hostec, A. J. Aguilar–Caballero, C. and M. Capetillo–Leal. 2009. Sheep preference for different tanniniferous tree fodders and its relationship with in vitro gas production and digestibility. Animal Feed Science and Technology 151:75–85. [ Links ]

Arellano, R. J. S., J. S. Flores and J. Tun–Garrido. 2003. Nomenclatura forma de vida, uso, manejo y distribución de las especies vegetales de la península de Yucatán. Fascículo No. 20. Etnoflora Yucatanense. Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia. UADY. 320 p. [ Links ]

Ayala, A. and S. M. Sandoval. 1995. Establecimiento y producción temprana de forraje de ramón (Brosimum alicastrum Sw.) en plantaciones a altas densidades en el norte de Yucatán, México. Agroforestería de las Américas 7:10–21. [ Links ]

BADEPY–INIREB (Banco de datos etnobotánicos de la Península de Yucatán–Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones sobre Recursos Bióticos). 1985. Centro de los recursos bióticos de la Península de Yucatán. INIREB. Veracruz, México. [ Links ]

Barrera, A., A. Barrera–Vázquez and R. M. López–Franco. 1976. Nomenclatura Etnobotánica Maya. Una interpretación Taxonómica. Colección científica 36 Etnología, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. México, D. F. 537 p. [ Links ]

Bautista, F. and J. A. Zinck. 2010. Construction of an Yucatec Maya soil classification and comparison with the WRB framework. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 6:7doi:10.1186/1746–4269–6–7. [ Links ]

Bautista, F., J. Jiménez–Osornio, J. Navarro–Alberto, A. Manu and R. Lozano. 2003a. Microrelieve y color del suelo como propiedades de diagnóstico en Leptosoles cársticos. Terra 21:1–11. [ Links ]

Bautista, F., E. Batllori, M. A. Ortiz, G. Palacio and M. Castillo. 2003b. Geoformas, agua y suelo en la Península de Yucatán. In Naturaleza y sociedad en el área maya, P. Colunga and A. Larque (eds.). Academia Mexicana de Ciencias y Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán. Yucatán, México. p. 21–35. [ Links ]

Bautista, F., E. Batllori, M. A. Ortiz, G. Palacio and M. Castillo. 2004a. El origen y el manejo maya de las geoformas, suelos y aguas en la Península de Yucatán. In Caracterización y manejo de suelos de la Península de Yucatán: Implicaciones Agropecuarias, Forestales y Ambientales, F. Bautista and G. Palacio (eds.). Universidad Autónoma de Campeche y Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán. Campeche, México. p. 21–32. [ Links ]

Bautista, F., E. Batllori, M. A. Ortiz, G. Palacio and M. Castillo. 2004b. Integración del conocimiento actual sobre las geoformas de la Península de Yucatán. In Caracterización y manejo de los suelos de la Península de Yucatán: implicaciones agropecuarias, forestales y ambientales, F. Bautista and G. Palacio (eds.). Universidad Autónoma de Campeche y Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán. Campeche, México. p. 33–58. [ Links ]

Bautista, F., S. Díaz, M. Castillo and A. J. Zinck. 2005. Soil heterogeneity in karst zone: Mayan Nomenclature, WRB, multivariate analysis and geostatistics. Eurasian Soil Science 38(S1):80–87. [ Links ]

Bautista, F., G. Palacio, P. Quintana and J. A. Zinck. 2011. Spatial distribution and development of soils in tropical karst areas from Yucatán, Mexico. Geomorphology 135:308–321. [ Links ]

Castillo–Caamal, J. B., J. A. Caamal–Maldonado, J. J. M. Jiménez–Osornio, F. Bautista, M. J. Amaya–Castro and R. Rodríguez–Carrillo. 2010. Evaluación de tres leguminosas como coberturas asociadas con maíz en el trópico subhúmedo. Agronomía mesoamericana 21:39–50. [ Links ]

Duch, J. 1988. La conformación territorial del estado de Yucatán. Los componentes del medio físico Centro Regional de la Península de Yucatán (CRUPY), Universidad Autónoma de Chapingo, Edo. de México, México. 180 p. [ Links ]

Duch, J. 2005. La nomenclatura maya de los suelos: una aproximación a su diversidad y significado en el sur del estado de Yucatán. In Caracterización y manejo de suelos en la Península de Yucatán, F. Bautista and G. Palacio (eds.). México, D. F. UACAM–UADY–INE. p. 73–86. [ Links ]

Flores, J. S. and I. Espejel. 1994. Tipos de vegetación de la península de Yucatán, Etnoflora yucatanense. Fascículo 3. Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán. Yucatán, México. 136 p. [ Links ]

Flores, J. S. 2001. Leguminosae (Florística, Etnobotánica y Ecología). Fascículo No. 18. Etnoflora Yucatanense. Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia. UADY. 320 p. [ Links ]

Flores, J. S. 2002. Guía ilustrada de la flora costera representativa de la península de Yucatán. Programa Etnoflora Yucatanense. Fascículo 19. Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán. 133 p. [ Links ]

García, E. 2004. Modificaciones al sistema de clasificación climática de Köppen, Serie Libros num. 6, 5a. ed., Instituto de Geografía, UNAM, México, D. F. 90 p. [ Links ]

Giraldo, V., I. A. Botero, A. J. Saldarriaga and P. David. 1995. Efecto de tres densidades de árboles en el potencial forrajero de un sistema silvopastoril natural, en la región atlántica de Colombia. Agroforesteria de las Americas 8:14–19. [ Links ]

Harvey, C. 2001. La conservación de la biodiversidad en sistemas silvopastoriles. Simposio Internacional sobre Sistemas Silvopastoriles y Segundo Congreso sobre Agroforestería y Producción de Ganado en América Latina, San José, Costa Rica. 3 al 7 de abril. http://www.lead.virtualcentre.org/es/ele/conferencia3/articulo2.htm; 11.V.2012. [ Links ]

Llamas, E., J. Castillo, C. A. Sandoval and F. Bautista. 2004. Producción y calidad de follaje de árboles forrajeros establecidos en minas de cal abandonadas. In Caracterización y manejo de los suelos de la Península de Yucatán: implicaciones agropecuarias, forestales y ambientales, F. Bautista y G. Palacio (eds.). Universidad Autónoma de Campeche y Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán.Campeche, México. p. 247–257. [ Links ]

López, E., C. A. Sandoval and R. C. Montes. 2007. Intake and digestivity of tree fodders by white tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus yucatanensis). Journal of Animal and Veterinary Advances 6:39–41. [ Links ]

López, M. A, J. A. Rivera, L. Ortega, J. G. Escobedo, M. A. Magaña, J. R. Sanginés and A. Carmelo. 2008. Contenido nutritivo y factores antinutricionales de plantas nativas forrajeras del norte de Quintana Roo, Mexico. Técnica Pecuaria en México 46:205–215. [ Links ]

Mizrahi, P. A., L. Ramírez, J. Castillo and P. Pool. 1998. Sheep food assessing the nutrient content of fodders trees in Yucatán, México. Agroforestry today 10:11:13. [ Links ]

NAS (National Academic Science). 1979. Tropical legumes: resources for the future national. Academic Science. Washington D. C. 331 p. [ Links ]

Norton, B. W. 1994. The Nutritive Value of Tree Legumes. In ForageTree Legumes in Tropical Agriculture, R. Gutteridge and H. M. Shelton (eds.). CAB International, UK. p. 177–191. [ Links ]

NRC (National Research Council). 1989. Lost crops of the Incas. National Academy Press Washington D. C. 441 p. [ Links ]

Nsahlai, IV, N., N. Umunna and D. Negassa. 1995. The effect of multi–purpose tree digesta on in vitro gas production from napier grass or neutral–detergent fibre. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 69:519–528. [ Links ]

Ortega, L., J. E. Castillo and F. A. Rivas. 2009. Conducta ingestiva de bovinos Cebú adultos en leucaena manejada a dos alturas diferentes. Técnica Pecuaria en México 47:125–134. [ Links ]

Pool, L. and E. Hernández. 1987. Los contenidos de materia orgánica de suelos en áreas bajo el sistema agrícola de roza, tumba y quema: importancia del muestreo. Terra 5:81–92. [ Links ]

Ramírez, A. L. and F. J. Solorio. 1997. Leucena spp. En los sistemas de producción bovina: experiencias y oportunidades. In Alternativas para la identificación de sistemas ganaderos de doble propósito en el trópico, J. F. Santos (ed.). UADY. FMVZ. Mérida, México. p. 65–88. [ Links ]

Roshetko, J. M., D. O. Lantagne and M. A. Gold. 1998. In vitro digestibility and nutritive value of the leaves of native, naturalized, and recently introduced tree species in Jamaica. In Nitrogen fixing trees for fodder production, J. N. Daniel and J. M. Roshetko (eds.). Proceeding of an International workshop. Forest Farm and Community Tree Research Report. FACT Net. USA. p. 196–204. [ Links ]

Sánchez, C. 1993.Uso y manejo de la leña en X–uilub, Yucatán. Fascículo. No. 8. Etnoflora Yucatanense. Universidad autónoma de Yucatán. Yucatán, México. 117 p. [ Links ]

Sánchez, C. 1993. Uso y manejo de la leña en Xuilub, Yucatán. Etnoflora Yucatanense, Fascículo. No. 8. Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán. 117 p. [ Links ]

Sandoval, C. A., S. Anderson and J. D. Leaver. 1999. Influence of milking and restricted suckling regimes on milk production and calf growth in temperate and tropical enviroments. Animal Science 69:287–296. [ Links ]

Sandoval, C. A., H. L. Lizarraga and F. J. Solorio–Sánchez. 2005. Assessment of tree fodder preference by cattle using chemical composition, in vitro gas production and in situ degradability. Animal Feed Science and Technology 123–124:277–289. [ Links ]

Santos R. H. and J. E. Abreu. 1995. Evaluación nutricional de Leucaena leucocephala y Brosimun alicastrum y su empleo en la alimentación de cerdos. Veterinaria Mexico 26:51–57. [ Links ]

Solorio, F. J. and B. Solorio. 2002. Integrating fodder trees into animal production systems in the tropics. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems 1:1–11. [ Links ]

Solorio, J. F., I. R. Armendáriz and J. Ku. 2000. Chemical content and in vitro dry matter digestibility of some fooder trees from the south east México. Livestock Research and Rural Development 12(4). http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd12/4/cont124.htm; 11.V.2012. [ Links ]

Sosa, V., J. S. Flores, V. Rico, R. Lira and J. J. Ortiz. 1985. Lista florística y sinonimia maya. Fascículo. No.1 de Etnoflora Yucatanense, INIREB, XAL, Veracruz, México. 225 p. [ Links ]

Sosa, E. E., L. I. Sansores, G. J. Zapata and L. Ortega. 2000. Botanical composition and nutritive value of cattle diet in secondary vegetation in Quintana Roo. Técnica Pecuaria en México 38:105–117. [ Links ]

Sosa, E. E., D. Pérez, L. Ortega and G. J. Zapata. 2004. Tropical trees and shrubs forage potential for sheep feeding. Técnica Pecuaria en México 42:129–144. [ Links ]

Sousa, M. and C. Cabrera. 1983. Listado florístico de México II. Flora de Quintana Roo. Instituto de Biología, UNAM. México, D. F. 100 p. [ Links ]

Standley, P. C. 1930. Flora of Yucatan. Publication, Field Museum of Natural Hisory. Botanic Series 3:157–492. [ Links ]

Vargas, P. 2004. El misterio maya. Revista InterSedes 5:1–16 [ Links ]

Vargas, B., E. Hugo, G. Pablo and S. Elvira. 1987. Composición química, digestibilidad y consumo de Leucaena (Leucaena leucocephala). Madre de cacao (Gliricidia sepium) y caulote (Guazuma ulmifolia). In Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Walp.: Management and Improvement, D. Withington, N. Glover and J. L. Brewbaker (eds.). Proceedings of a workshop at CATIE, Turrialba Costa Rica. NFTA Special Publication 87–01. p. 217–222. [ Links ]

Yerana, F., H. M. Ferreiro, R. Elliot, R. Godoy and T. R. Preston. 1978. Digestibilidad del ramón (Brosimun alicastrum), Leucaena leucocephala, pasto buffel (Cenchrus ciliaris) y pulpa y bagazo de henequén (Agave fourcroydes). Producción Animal Tropical 3:70–73. [ Links ]

Zapata, G., F. Bautista and M. Astier. 2009. Caracterización forrajera de un sistema silvopastoril de vegetación secundaria con base en la aptitud de suelo. Técnica Pecuaria en México 47:257–270. [ Links ]