Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Journal of the Mexican Chemical Society

Print version ISSN 1870-249X

J. Mex. Chem. Soc vol.57 n.3 Ciudad de México Jul./Sep. 2013

Article

A Therapeutic System of 177Lu-labeled Gold Nanoparticles-RGD Internalized in Breast Cancer Cells

Myrna Luna-Gutiérrez,1,2 Guillermina Ferro-Flores,1* Blanca E. Ocampo-García,1 Clara L. Santos-Cuevas,1 Nallely Jiménez-Mancilla,1,2 De León-Rodríguez L.M.,3 Erika Azorín-Vega,1 and Keila Isaac-Olivé2

1 Departamento de Materiales Radiactivos, Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Nucleares, Estado de México, México. ferro_flores@yahoo.com.mx; guillermina.ferro@inin.gob.mx

2 Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, Estado de México, México.

3 Departamento de Química, Universidad de Guanajuato, Guanajuato, México.

Received March 21, 2013

Accepted June 10, 2013

Abstract

The aim of this research was to evaluate the in vitro potential of 177Lu-labeled gold nanoparticles conjugated to cyclo-[RGDfK(C)] peptides (177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)]) as a plasmonic photothermal therapy and targeted radiotherapy system in MCF7 breast cancer cells. Peptides were conjugated to AuNPs (20 nm) by spontaneous reaction with the thiol group of cysteine (C). After laser irradiation, the presence of c[RGDfK(C)]-AuNP in cells caused a significant increase in the temperature of the medium (50.5 °C, compared to 40.3 °C without AuNPs) resulting in a significant decrease in MCF7 cell viability down to 9 %. After treatment with 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)], the MCF7 cell proliferation was significantly inhibited.

Key words: gold nanoparticles; radiolabeled nanoparticles; radio-gold nanoparticles; radiolabeled peptides; nanoparticle-peptide; RGD peptide; lutetium-177.

Resumen

El objetivo de esta investigación fue evaluar el potencial in vitro de las nanopartículas de oro marcadas con 177Lu y conjugadas al péptido ciclo-[RGDfK(C)] (177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)]) como un sistema de terapia fototérmica plasmónica y radioterapia dirigida en células de cáncer de mama MCF7. Los péptidos se conjugaron por reacción espontánea de los grupos tiol de la cisteína (C) con la superficie de las AuNPs (20 nm). Después de la irradiación láser, la presencia de c[RGDfK(C)]-AuNP en las células causó un incremento significativo en la temperatura del medio (50.5 °C, comparado con 40.3 °C de las células sin AuNPs), lo que resultó en una disminución significativa en la viabilidad de las células MCF7 hasta el 9 %. Después del tratamiento con 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)], la proliferación de las células MCF7 fue inhibida significativamente.

Palabras clave: nanopartículas de oro; nanopartículas radiomarcadas; radio-nanopartículas; péptidos radiomarcados; nanopartículas-péptidos; péptido RGD; lutecio-177.

Introduction

Target-specific radiopharmaceuticals are unique in their ability to monitor receptor binding sites in vivo for diagnostic or therapeutic applications [1]. Radiolabeled peptides based on the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) sequence have been reported as radiopharmaceuticals with high affinity and selectivity for α(ν)β(3) and α(ν)β(5) integrins. These peptides are thus useful in the non-invasive monitoring of tumor angiogenesis by molecular imaging techniques [2-4].

In breast cancer, α(ν)β(3) and/or α(ν)β(5) integrins are over-expressed in both endothelial and tumor cells [5, 6]. Monomeric RGD radiopharmaceuticals tend to have fast blood clearance but relatively good tumor uptake and rapid tumor washout, whereas dimeric, tetrameric, and octameric cyclic-RGD peptides exhibit increased affinity and enhanced adhesion to target integrins due to an increase in multivalent sites [7-10].

Radiolabeled gold nanoparticles can be used to prepare multivalent radiopharmaceuticals [4, 8]. Large numbers of peptides can be conjugated to one gold nanoparticle (AuNP) by a spontaneous reaction of the AuNP surface with a thiol (cysteine) or an N-terminal primary amine [10-13]. The thiol group is considered to be the most important type of molecule for stabilizing any AuNP size by forming a "staple" motif model of two thiol groups interacting with three gold atoms in a bridge conformation [14]. AuNPs coated with peptides exhibit increased stability and biocompatibility, allowing them to be directed to the desired target [15, 16].

Gold nanoparticles undergo plasmon resonance when exposed to light. In this process, the electrons of gold resonate in response to incoming radiation, causing them both to absorb and scatter light. Generally, AuNPs release heat following the absorption of non-ionizing energy. Once attached to their receptors, AuNPs can be heated with ultraviolet-visible/infrared or radiofrequency pulses, thus heating the surrounding area of the cell and inducing irreversible thermal cellular destruction [17-19].

177Lu is a radionuclide with a half-life of 6.71 d, a βmax emission of 0.497 MeV (78%) and γ radiation of 0.208 MeV (11%) and forms a stable coordination complex with the 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-N,N',N'',N'''-tetraacetic acid (DOTA). 177Lu has been used successfully for radiopeptide therapy with an efficient cross-fire effect in cancer cells [20].

A radiopharmaceutical of the type 177Lu-DOTA-Gly-Gly-Cys-AuNP (177Lu-AuNP) conjugated to hundreds of cyclo[Arg-Gly-Asp-Phe-Lys(Cys)] peptides (c[RGDfK(C)]), may function simultaneously as both a radiotherapy system (i.e., high β-particle energy delivered per unit of targeted mass) and a thermal ablation system (i.e., localized heating after laser irradiation) in cancer cells over-expressing the α(ν)β(3) and/or α(ν)β(5) integrins. An injection of the multifunctional system into an artery of the affected organ would allow for high uptake to a tumor, possible micrometastases or individual cancer cells.

The aim of this research was to evaluate the in vitro potential of 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] as a plasmonic photothermal therapy and targeted radiotherapy system in MCF7 breast cancer cells.

Results and discussion

Chemical characterization

The synthesis and chemical characterization of DOTA-GGC and c[RGDfK(C)] were previously reported as well as the preparation and dosimetry of 177Lu-DOTA-GGC-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] [8,10]. The results related to the chemical characterization of the conjugate DOTA-GGC-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] (Fig. 1A) used in this research are briefly discussed in this section.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The images of DOTA-GGC-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] showed monodispersed solutions. The increase in the hydrodynamic diameter of the particle by the peptide conjugation-effect was observed by TEM as a low electronic density around the gold nanoparticle due to the poor interaction of the electron beam with the peptide molecules (low electron density), in contrast to the strong scattering of the electron beam when it interacted with the metallic nanoparticles (Fig. 1B).

Particle size and zeta potential. The average particle hydrodynamic diameter determined by light scattering was 21.22 ± 7.21 nm (Fig. 1B). The Z potential of the DOTA-GGC-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] was -72 ± 3.8 mV versus -63±2.7mV for the AuNP, indicating that the peptide functionalization confers a high colloidal stability to the nanosystem [21].

XP spectroscopy. The AuNP spectrum (Fig. 1C) showed two main peaks corresponding to the binding energies (B.E., eV) of the electrons in Au 4f orbitals at 87.5 eV (Au 4f5/2) and 83.8 eV (Au 4f7/2), with a characteristic difference of 3.7 eV and an intensity ratio of 3:4 between the two peaks [22]. The c[RGDfK(C)]-AuNP spectrum (Fig. 1C) showed two additional peaks at 89.2 eV and 84.1 eV, with a positive shift due to atoms with different oxidation states. The orbital energies of Au-Au or Au-citrate (Au0) and Au-S- (Au+1) bonds are related to changes in the oxidation states (Au0 to Au+1), so the shift of electron binding energies to higher values is an intrinsic property of the interaction between gold core electrons and peptides [22]. In the XP-spectrum of DOTA-GGC-AuNP, the shift of electron binding energies to higher values while having low intensity indicates that more than one type of interaction may occur between NH2 (which belongs to the amide group) and the Au-surface, as the NH2 groups could also form hydrogen bonds.

Raman spectra. AuNPs that were functionalized with c[RGDfK(C)] yielded a structured Raman spectrum in the 1800-600 cm-1 region. Several well-defined bands were observed that had vibrational frequencies in the regions of those associated with the main functional groups observed in the c[RGDfK(C)] spectrum, but they were characteristic of c[RGDfK(C)]-AuNP and DOTA-GGC-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] because of the shifts to lower or higher energies and similar increases in the band intensities (Table 1).

Far-infrared spectroscopy. Both c[RGDfK(C)]-AuNP and DOTA-GGC-AuNP showed a characteristic band at 279 ± 1 cm-1, which was assigned to the Au-S bond (Fig. 1D) [23]. However, the DOTA-GGC-AuNP band at 278 cm-1 is of low resolution, corroborating that the Au-S bond in the DOTA-GGC-AuNP conjugate is not the only form of interaction. In agreement with Petroski et al. [23], the group vibrations occurring in the far-IR region, such as the Au-S stretch as well as the C-S stretch and CC-C- or S-C-C deformations. The multiple peaks of the νAu-S (in the range of 200-280 cm-1) may reflect the local heterogeneities for different types of binding sites on the particle surface. Heterogeneity can be attributed to the fact that a nanoparticle surface contains various types of defect sites, which can include edge, ledge, step, or kink sites, among others.

UV-Vis spectroscopy. The AuNP spectrum showed a surface plasmon resonance at 520 nm (Fig. 1E). A red-shift to 522 nm was observed in the c[RGDfK(C)]-AuNP and DOTA-GGC-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] spectra due to changes in the refraction index and the surrounding dielectric medium, which occurred as consequence of the interaction between the peptide and the AuNP surface [24].

Preparation of the 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] and 177Lu-AuNP

After the labeling procedure, the radiochemical purity of 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] and 177Lu-AuNP was 96 ± 2 % (n = 20) without post-labeling purification. In both radiopharmaceuticals, the specific activity was 50 kBq/pmol. Previously, we had prepared 177Lu-labeled gold nanoparticles with specific activities that were 350 times higher than that reported in this study; however, for in vitro studies, it was calculated that from 3 to 5 Bq of 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] internalized in the cytoplasm of each MCF7 cell would be sufficient to produce a radiation-absorbed dose of 100 Gy to the nucleus [8,16,25] within 3 days. For in vitro comparative purposes, 177Lu-DOTA-E-[c(RGDfK)]2 (177Lu-RGD) without AuNP was obtained with a radiochemical purity of 98 ± 1%, following the procedure described in the experimental section.

Human serum stability

177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] diluted in human serum was stable for 24 h because at this time the radiochemical purity was 92.0 ± 1.1%. The 522 nm surface plasmon resonance, which is characteristic of gold nanoparticles, remained stable and was slightly shifted to higher energy (524 nm) because of the protein interactions.

Solid-phase α(v)β(3) binding assay: in vitro affinity

The in vitro affinity, which was determined by a competitive binding assay, indicated that the concentration of c(RGDfK) required to displace 50% of the 177Lu-AuNP- c[RGDfK(C)] (IC50 = 10.2 ± 1.1 nM) or 177Lu-RGD (IC50 = 5.3 ± 0.4 nM) from the receptor was the same order of magnitude for both, demonstrating high in vitro affinity for the α(v)β(3) integrin for both conjugates. However, the amount of c(RGDfK) required to displace 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] from the α(v)β(3) protein was twice to that necessary to displace the 177Lu-RGD, which may be attributed to the multivalent effect of the AuNP system [4, 7].

Internalization assay and non-specific binding

As shown in Table 2, 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] had specific recognition because the integrin receptor positive cell internalization was 2 times higher than that of 177Lu-AuNP (p < 0.05), and its specificity was confirmed with the receptor blocking study (Table 2). The 177Lu-AuNP accumulation (15.72 ± 2.13%) in MCF7 cells could have been related to passive uptake because gold nanoparticles can be taken up by all mammalian cells due to the particle nanometric size (20 nm) [26]. However, with the conjugation of c[RGDfK(C)] to the AuNPs, the tumor cell internalization was significantly increased (32.31 ± 4.08%). The significant difference in cell binding results (32.31% in comparison to 15.72%) was due to active targeting, i.e., specific integrin receptor recognition. The 177Lu-RGD binding was specific, although it was significantly lower than that of 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] (p < 0.05), which can be attributed to the multivalent effect of the AuNP system [4, 7].

Cell viability after laser irradiation

As shown in Fig. 2, the presence of the gold nanoparticles caused the temperature of the medium to increase significantly under the laser irradiated conditions described below (50.5 °C, compared to 40.3 °C without AuNP, p < 0.05). As expected, the increase in temperature was similar for AuNP and c[RGDfK(C)]-AuNP, which indicates that changes in temperature are only determined by the size and concentration of gold nanoparticles in the medium [19].

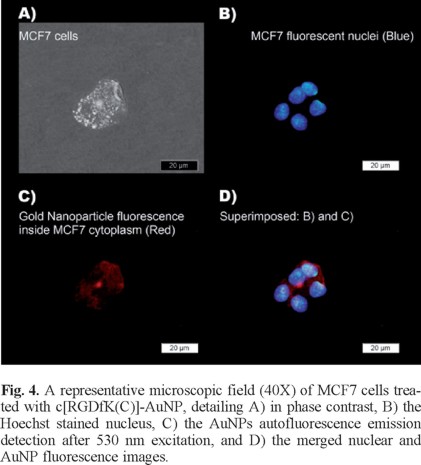

AuNP and c[RGDfK(C)]-AuNP significantly reduced MCF7 cell viability with respect to the laser irradiated cells treated without nanoparticles (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3). However, the c[RGDfK(C)]-AuNP system caused a significant decrease in cell viability (p < 0.05) down to 9% by the end of treatment (6 min) while the AuNP decreased to 18.5% (Fig. 3).If more AuNPs would have been used, cell death could be expected, which is in agreement with other studies [27, 28]. When MCF7 cells were incubated in a heating plate at 50 °C for 6 min, cell viability was 92 ± 2%. This result corroborated that the release of heat (the expected temperature around each nanoparticle is 727 °C [19]) in the cytoplasm of MCF7 cells (due to the interaction between c[RGDfK(C)]-AuNP and integrins with the consequent internalization) is the reason of the significant reduction in cell viability, not just the temperature increase in the medium during those few minutes. Moreover, the fluorescence microscopy images presented in Fig. 4 demonstrate that 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] was internalized in the cytoplasm of the MCF7 cells.

Several trials have demonstrated a significant improvement in the clinical outcome when radiotherapy was conducted under hyperthermic conditions in patients [29, 30]. Hyperthermia increases the efficacy of radiotherapy by improving tumor oxygenation and interfering with the DNA repair mechanisms [29]. However, the current techniques for hyperthermia induction display low spatial selectivity for the tissues that are heated. Lasers have been used to induce hyperthermia, and spatial selectivity can be improved by adding gold nanoparticles to the tissue to be treated [31]. By exposing nanoparticles to laser irradiation, it is possible to heat a localized area in the tumor without any harmful heating of the surrounding healthy tissues. The previous studies using AuNPs for hyperthermia have demonstrated that the functionalization of gold nanoparticles with probe molecules improves significantly the particle accumulation in cell models [31-33]. In this study, we have demonstrated that the conjugation of c[RGDfK(C)] to gold nanoparticles significantly reduces MCF7 breast cancer cell viability in comparison to AuNPs after laser irradiation.

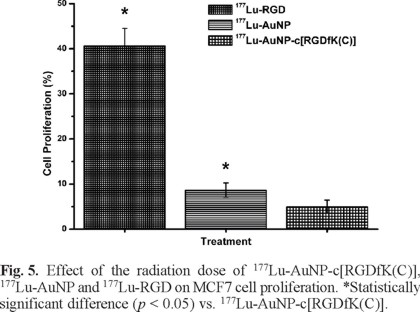

Cell proliferation after 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)], 177Lu-AuNP and 177Lu-RGD treatments.

As shown in Fig. 5, 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] significantly inhibited MCF7 cell proliferation with respect to that of 177Lu-AuNP and177Lu-RGD (p < 0.05), which was attributed to the greater MCF7 cell internalization as a result of multivalency. An important benefit of receptor-specific radiopharmaceuticals is their use for targeted radiotherapy. Multiple specific c[RGDfK(C)] peptides to target integrins that are overexpressed in breast cancer cells, appended to one gold nanoparticle and radiolabeled with an imaging and β-particle-emitting radionuclide (177Lu), act as a multifunctional system that might be useful in identifying malignant tumors and metastatic sites (by single photon emission computed tomography imaging, SPECT), for targeted radiotherapy (high β-particle-energy delivered per unit of targeted mass) and for thermal therapy (localized heating after laser irradiation). However, for therapeutic purposes, NPs should be administered by intratumoral injection or into a selective artery to avoid high uptake by organs of the reticulo-endothelial system due to the colloidal nature of NPs [33]. Injection into a breast tumor would allow for high uptake to a tumor, possible micrometastases or individual cancer cells. Therefore, 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] has potential application in medical diagnosis and therapeutic treatments due to its unique combination of radioactive, optical and thermoablative properties. This study demonstrated that the nanosystem exhibited properties that are suitable for plasmonic photothermal therapy and targeted radiotherapy in the treatment of breast cancer.

Experimental

Synthesis of gold nanoparticles (AuNP solution)

AuNPs were prepared by the conventional citrate reduction of tetrachloroauric acid [24]. Before the reduction process, all glassware was cleaned in "aqua regia" (i.e., 3 parts HCl, 1 part HNO3), rinsed with deionized water and placed in a dry heat sterilizer (Felisa(R), Mexico City, Mexico). The AuNP preparation was carried out under aseptic conditions in a Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP)certified facility. An aqueous solution (100 mL, injectable-grade water) of 1.7 mM trisodium citrate dehydrate (Sigma-Aldrich) was heated to boiling and stirred continuously. Next, 0.87 mL of 1% tetrachloroauric acid (HAuCl4.3H2O, Sigma-Aldrich) was added quickly, resulting in a change in the solution color from pale yellow to black to deep red. The AuNP solution was dialyzed against injectable-grade water (2 times with 0.5 L) for 6 h, reduced to 1/5 of the original volume under vacuum and sterilized by membrane filtration (Millipore, 0.22 µm).

Absorption spectra in the range of 400-800 nm were obtained with a Perkin-Elmer Lambda-Bio spectrometer using a 1 cm quartz cuvette to monitor the characteristic AuNP surface plasmon band at 522 nm (3.5 × 1012 particles/mL, ODλ=522 = 0.9 diluted 1/5). For the radiolabeling procedure, the concentration of gold nanoparticles was 6.99 × 1011 particles/mL (1.1 nM).

Conjugation of peptides to AuNPs

Previously we reported the synthesis of DOTA-GGC (1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-N',N",N"'-tetraacetic-Gly-Gly-Cys) and cyclo[Arg-Gly-Asp-Phe-Lys(Cys)] (c[RGDfK(C)]) with a purity of > 98%, as analyzed by reversed-phase HPLC (RP-HPLC) and mass spectroscopy [8,10]. In the c[RGDfK(C)] molecule, the sequence -Arg-Gly-Asp- (-RGD-) acts as the active biological site, the D-Phe (f) and Lys (K) residues completed the cyclic and pentapeptide structure, and Cys (C) is the spacer and active thiol group that interacts with the gold nanoparticle surface (Fig. 1A). In the DOTA-GGC molecule, the sequence GG is the spacer, cysteine (active thiol group) is used to interact with the gold nanoparticle surface and DOTA is used as the lutetium-177 chelator (Fig. 1A).

For the conjugates preparation, a 50 µM solution of either c[RGDfK(C)] or DOTA-GGC was prepared using injectable-grade water. Then, 0.02 mL of solution (6.023×1014molecules/mL) was added to 1 mL of the AuNP solution (20 nm, 3.5 × 1012 particles/mL) followed by stirring for 5 min. Under these conditions, an average of 172 molecules of c[RGDfK(C)] or DOTA-GGC were attached per nanoparticle (20 nm, surface area = 1260 nm2, 37,000 surface Au atoms). No further purification was required since we have evaluated that the maximum number of peptides that can be bound to one AuNP (20 nm) is from 520 to 1701 depending of the peptide structure [10].The number of peptides per nanoparticle was calculated by UV-Vis titration of peptides (8 µM) using increasing gold nanoparticle concentration (from 0 to 1 nM) [10]. Both peptides were added simultaneously for the preparation of DOTA-GGC-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)].

Chemical characterization

TEM. The peptide-conjugated gold nanoparticles were characterized in size and shape by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) using a JEOL JEM 2010 HT microscope operated at 200 kV. The samples were prepared for analysis by evaporating a drop of the aqueous product onto a carbon-coated TEM copper grid.

Particle size and zeta potential. Measurements of the AuNP or DOTA-GGC-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] consisted of 5 repeats of each solution using a particle size (dynamic light scattering) and Z potential analyzer (Nanotrac Wave, Model MN401, Microtract, FL, USA).

Far-infrared, UV-Vis, Raman and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy of the AuNPs and AuNP-peptides were performed according to the methods described by Luna-Gutiérrez et al [8].

Preparation of the 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)], 177Lu-AuNP and 177Lu-RGD

177LuCl3 preparation. 177Lu was produced by neutron capture of the highly enriched 176Lu2O3 target (176Lu, 64.3%; Isoflex, USA). The irradiations were performed in the central thimble of the TRIGA Mark III reactor (Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Nucleares, Mexico) at a neutron flux of 3 × 1013 n⋅s -1·cm -2. Typically, 1 mg of 176Lu2O3 was irradiated for 20 h. The target was allowed to decay for 5 h, at which time 0.1 mL of 12 M HCl was added and the solution was stirred for 2 h. Next, 1.9 mL of injectable-grade water was added to the solution. The average specific activity of the 177Lu chloride solution was 1.7 GBq/µmol, which was diluted to 0.25 mM using injectable water.

Preparation of 177Lu-DOTA-GGC. A 15-μL aliquot of DOTA-GGC (1 mg/mL) was diluted with 50 μL of 1 M acetate buffer at pH 5, followed by the addition of 7 μL (3 MBq) of the 177LuCl3 solution. The mixture was incubated at 90 °C in a block heater for 30 min. The solution was diluted to 1.5 mL with injectable water. A radiochemical purity >98% was verified by TLC silica gel plates (aluminum backing, Merck); 10 cm strips were used as the stationary phase, and ammonium hydroxide:methanol:water (1:5:10) was used as the mobile phase to determine the amount of free 177Lu (Rf = 0) and 177Lu-DOTA-GGC (Rf = 0.4-0.5). The radiochemical purity was determined by reversed phase HPLC on a C-18 column (µ-Bondapack C-18, Waters) using a Waters Empower system with an in-line radioactivity detector and a gradient of water/acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA from 95/5 to 20/80 in 35 min at 1 mL/min (177LuCl3 tR = 3 min; 177Lu-DOTA-GGC tR = 16 min).

Preparation of 177Lu-labeled AuNPs. To 1 mL of AuNP (20 nm), 0.025 mL of c[RGDfK(C)] (5 µM; 108 molecules per 20 nm nanoparticle) was added, followed by 0.025 mL (50 kBq) of 177Lu-DOTA-GGC (1.89 × 1014 molecules; 270 molecules per 20 nm AuNP), and the mixture was stirred for 5 min to form the 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] system. No further purification was performed. The same procedure was performed for the preparation of 177Lu-AuNP but with the addition of 0.025 mL of water instead of the c[RGDfK(C)] solution.

The radiochemical purity was evaluated by size-exclusion chromatography and ultrafiltration. A 0.1 mL sample of 177LuAuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] was loaded into a PD-10 column, and injectable water was used as the eluent. The first radioactive and red eluted peak (3.0-4.0 mL) corresponded to the radiolabeled c[RGDfK(C)]-AuNP. The free radiolabeled peptide (177Lu-DOTAGGC) appeared in the 5.0-7.0 mL eluted fraction, and 177LuCl3 remained trapped in the column matrix. Using ultrafiltration (Centicron YM-30 Regenerated cellulose 30,000 MW cut off, Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA), the 177Lu-labeled nanoparticles remained in the filter, while free 177Lu-DOTA-GGC and 177LuCl3 passed through the filter. In the radio-HPLC size exclusion system (ProteinPak 300SW, Waters, 1 mL/min, injectable water), the tRs for the 177Lu-labeled AuNPs and 177Lu-DOTA-GGC were 4.0-4.5 and 8 min, respectively.

Preparation of 177Lu-RGD. For comparative in vitro studies, DOTA-E-c(RGDfK)2 was synthesized by Peptide International Inc. (Kentucky, USA) with a purity that was >98%, as analyzed by reversed phase HPLC (RP-HPLC) and mass spectroscopy. A 5-μL aliquot of DOTA-E[c(RGDfK)2 (1 mg/mL) was diluted with 50 μL of 1 M acetate buffer at pH 5, followed by the addition of 7 μL of the 177LuCl3 solution. The mixture was incubated at 90 °C in a block heater for 30 min and diluted to 50 kBq/mL with injectable-grade water. A radiochemical purity >98% was verified by TLC and HPLC, as described above for 177Lu-DOTA-GGC.

In vitro stability assay of 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] in human serum

To determine the stability of 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] in serum, 200 μL of radiolabeled gold nanoparticles was diluted at a ratio of 1:5 with fresh human serum and incubated at 37 °C. The chemical stability was determined by UV-Vis analysis to monitor the AuNP surface plasmon resonance band (520 nm) at 1 h and 24 h after dilution. The radiochemical stability was determined by taking samples of 0.01 mL at 1 h and 24 h for ultrafiltration, as described above.

Cell culture

The MCF7 cell line was originally obtained from ATCC (Atlanta, GA, USA). The cells were routinely grown at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and 85% humidity in minimum essential medium eagle (MEM, Sigma-Aldrich Co., Saint Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 µL of estradiol (1 µM) and antibiotics (100 units/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin).

Solid-phase α(v)β(3) binding assay

Microtiter 96-well vinyl assay plates (Corning, NY, USA) were coated with 100 μL/well of purified human integrin α(v)β(3) solution (150 ng/mL, Chemicon-Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA) in coating buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM MnCl2) for 17 h at 4 °C. The plates were washed twice with binding buffer (0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in coating buffer). The wells were blocked for 2 h with 200 μL of blocking buffer (1% BSA in coating buffer). The plates were washed twice with binding buffer. Then, 100 μL of binding buffer containing 10 kBq of 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] or 177Lu-RGD and appropriate dilutions (from 10,000 nM to 0.001 nM of c(RGDfK), Bachem-USA) in binding buffer were incubated in the wells at 37 °C for 1 h. After incubation, the plates were washed three times with binding buffer. The wells were cut out and counted in a gamma counter. The IC50 values of the RGD peptides were calculated by nonlinear regression analysis (n = 5).

Internalization assay and non-specific binding

MCF7 cells supplied in fresh medium were diluted to 1 x 106 cells/tube (0.5 mL) and incubated with approximately 200,000 cpm of either 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)], 177Lu-AuNP or 177Lu-RGD (10 µL, 0.3 nmol total peptide) in triplicate at 37 °C for 2 h. The test tubes were centrifuged (3 min, 500 g) and washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The radioactivity in the cell pellet represents both the externalized radiomolecule (surface-bound) and internalized radiomolecule (internal membrane-bound radioactivity). The externalized peptide activity was removed with 1 mL of 0.2 M acetic acid/0.5 M NaCl solution added to the resuspended cell pellet. The test tubes were centrifuged, washed with PBS, and re-centrifuged. The pellet activity, as determined in a crystal scintillation well-type detector, was considered as internalization. An aliquot with the initial activity was taken to represent 100 %, and the cell uptake activity with respect to this value was then calculated. The non-specific binding was determined in parallel, using 0.05 mM c(RGDfK) (Bachem-USA), which blocked the cell receptors.

Laser irradiation

All experiments were conducted using a Nd:YAG laser (Minilite, Continuum®, Photonic Solutions, Edinburgh, U.K.) pulsed for 5 ns at 532 nm (energy = 25 mJ/pulse) with a repetition rate of 10 Hz. The per-pulse laser power was measured using a Dual-Channel Joulemeter/Power Meter (Molectron EPM 2000, Coherent). A diverging lens was used in the path of the laser beam such that the well plate was fully covered by the laser (diameter = 7 mm, area = 0.38 cm2). The irradiance at the well plate was then calculated as the laser power per pulse divided by the laser spot area. Irradiation was performed for 6 min while delivering 0.65 W/cm2 of average irradiance.

MCF7 cells (two different cultures) supplied with fresh medium were incubated in a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 103cells/well. The cells were cultured for 24 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and 85 % humidity. The growth medium was removed, the well plate was placed in a dry block heater at 37 °C, and the cells were exposed to one of the following treatments (n = 6): a) 100 µL of AuNP and 100 µL of PBS, pH 7 with irradiation (0.65 W/cm2), b) 100 µL of c[RGDfK(C)]-AuNP and 100 µL of PBS pH 7 with irradiation (0.65 W/cm2), c) 100 µL of distilled water (without nanoparticles) and 100 µL of PBS pH 7 with irradiation (0.65 W/cm2), d) no treatment or e) placed for 6 min in a plate heated to 50 °C without laser irradiation (Microplate Thermo Shaker, Human Lab MB100-2A, Hangzhou Zhejia, China). During laser irradiation, the temperature increase was measured using a type k thermocouple (model TP-01) of immediate reaction that had been previously calibrated (probe diameter = 0.8 mm). The thermocouple was introduced into the well, and the temperature was registered each second using a digital multimeter connected to a computer. After irradiation, the solution of each well was removed and replaced with fresh growth medium. The percentage of surviving cells in each well was evaluated by the spectrophotometric measurement of cell viability as a function of mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity, which involves the cleavage of the tetrazolium ring of XTT (sodium 3'-[1-[phenylaminocarbonyl]3,4-tetrazolium]-bis[4-methoxy-6-nitro]benzene sulfonic acid hydrate) in viable cells to yield orange formazan crystals that are dissolved in acidified isopropanol (XTT kit, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The resulting absorbance of the orange solution was measured at 480 nm in a microplate absorbance reader (EpochTM, BioTek, VT, USA). The absorbance of the untreated cells was considered to be 100% of the MCF7 cell viability.

Radiotherapeutic treatment

MCF7 cells supplied with fresh medium were incubated in a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 103 cells/well. The cells were cultured for 24 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and 85% humidity. The growth medium was removed, and the cells were exposed for 2 h (at 37 °C, with 5% CO2 and 85% humidity) to one of the following treatments (n = 6): a) 100 µL of 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] (5 kBq) and 100 µL of PBS, pH 7, b) 100 µL of 177Lu-AuNP (5 kBq) and 100 µL of PBS, pH 7, c) 100 µL of 177Lu-RGD (5 kBq) and 100 µL of PBS, pH 7, or d) no treatment. After 2 h, the solution in each well was removed and replaced with fresh growth medium. The cells were cultured for 3 days (at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and 85% humidity). After that, the percentage of cell proliferation in each well was evaluated using the XTT kit method, as described above. The absorbance of the untreated cells was considered to be 100 % MCF7 cell viability.

Fluorescence microscopy images

MCF7 cells were incubated with 0.25 mL of 177Lu-AuNP-c[RGDfK(C)] and 0.25 mL of PBS at pH 7 for 2 h. After treatment, the cells were immediately rinsed with ice cold PBS, fixed in acetone and washed twice with PBS. After the addition of 250 µL (1 µg/mL) of Hoechst (DNA stain), cells were incubated for 1 min at room temperature and rinsed with PBS before being mounted onto slides (ProLong Gold; Molecular Probes, Invitrogen Life Technologies, California, USA). Images of fluorescent gold nanoparticles internalized in the MCF7 cytoplasm were taken using an epi-fluorescent microscope (Meiji Techno MT6200, Saitama, Japan) with an excitation filter of 330-385 nm and an emission filter of 420 nm to visualize the Hoechst dye inside the nuclei and an excitation filter of 530-550 nm and an emission filter of 590 nm to detect the fluorescence of the AuNPs.

Statistical analysis

Differences between the in vitro cell data were evaluated with Student's t-test (significance was defined as p<0.05).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the support of the Mexican National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT-SEP-CB-201001-150942).

References

1. Ferro-Flores, G.; Murphy, C.A.; Melendez-Alafort, L. Curr. Pharm. Anal. 2006, 2, 339-352. [ Links ]

2. Hynes, R.O.J. Thromb. Haemost. 2007, 5 (Suppl. 1), 32-40. [ Links ]

3. Haubner, R.; Decristoforo, C. Front.Biosci. 2009,14, 872. [ Links ]

4. Montet, X.; Funovics, M.; Montet-Abou, K.; Weissleder, R.; Lee, J. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 6087-6093. [ Links ]

5. Taherian, A.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. ; Haas, T.A. BMC Cancer. 2011, 11:293,doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-293. [ Links ]

6. Pointer, S.M.; Muller, W.J. J. Cell Sci. 2009, 122, 207-214. [ Links ]

7. Z. Li, W. Cai, Q. Cao, K. Chen, Z. Wu, X. Chen, J. Nucl. Med. 2007, 48, 1162-1171. [ Links ]

8. Luna-Gutierrez, M.; Ferro-Flores, G.; Ocampo-Garcia, B.E.; Jimenez-Mancilla, N.P.; Morales-Avila, E.; De Leon-Rodriguez, L.M.; Isaac-Olive, K. J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm. 2012, 50, 140-148. [ Links ]

9. Kubas, H.; Schäfer, M.; Bauder-Wüst, U.; Eder, M.; Oltmanns, D.; Haberkorn, U.; Mier, W.;Eisenhut, M. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2010, 37, 885-891. [ Links ]

10. Morales-Avila, E.; Ferro-Flores, G.; Ocampo-Garcia, B.E.; Leon-Rodriguez, L.M.; Santos-Cuevas, C.L.; Medina, L.A. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011, 22, 913-922. [ Links ]

11. Levy, R.; Thanh, N.T.K.; Doty, R.C.; Hussain, I.; Nichols, R.J.; Schiffrin, D.J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 10076-10084. [ Links ]

12. Mendoza-Sanchez, A.N.; Ferro-Flores, G.; Ocampo-Garcia, B.E.; Morales-Avila, E.; Ramirez, F.deM.; Leon-Rodriguez, L.M. J. Biomed. Nanotech. 2010, 6, 375-384. [ Links ]

13. Porta, F.; Speranza, G.; Krpetic, Z.;Santo, V.D.; Francescato, P.; Scari, G. Mater. Sci. Eng. B. 2007, 140, 187-194. [ Links ]

14. Jadzinsky, P.D.; Calero, G.; Ackerson, C.J.; Bushnell, D.A.; Komberg, R.D. Science. 2007, 318, 430-433. [ Links ]

15. Ocampo-Garcia, B.E.; Ramirez, F. de M.; Ferro-Flores, G.; Leon-Rodriguez, L.M.; Santos-Cuevas, C.L.; Morales-Avila, E.; Murphy, C.A.; Pedraza-Lopez, M.; Medina, L.A., Camacho-Lopez, M.A. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2011, 38, 1-11. [ Links ]

16. Jimenez-Mancilla, N.P.; Ferro-Flores, G.; Ocampo-Garcia, B.E.; Luna-Gutierrez M.A.; Ramirez F. de M.; Pedraza-Lopez, M.; Torres-Garcia, E. Curr. Nanosci. 2012, 18, 193-201. [ Links ]

17. Curley, S.A.; Cherukuri, P.; Briggs, K.; Patra, C.R.; Upton, M.; Dolson, E.; Mukherjee, P. J. Exp. Ther. Oncol. 2008, 7, 313-326. [ Links ]

18. Glazer, E.S.; Zhu, C.; Massey, K.L.; Thompson, C.S.; Kaluarachchi, W.D.; Hamir, A.N.; Curley, S.A. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 5712-5721. [ Links ]

19. Letfullin, R.R.; Iversen, C.B.; George, T.F. Nanomedicine. 2011, 7, 137-145. [ Links ]

20. Bodei, L.; Cremonesi, M.; Ferrari, M.; Pacifici, M.; Grana, C.M.; Bartolomei, M.; Baio, S.M.; Sansovini, M.; Paganelli, G. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008, 35, 1847-1856. [ Links ]

21. Olmedo, I.; Araya, E.; Sanz, F.; Medina, E.; Arbiol, J.; Toledo, P.; Alvarez-Lueje, A.; Giralt, E.; Kogan, M.J. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008, 19, 1154-1163. [ Links ]

22. Joseph, Y.; Besnard, I.; Rosenberger, M.; Guse, B.; Nothofer, H.G.; Wessels, J.M.; Wild, U.; Knop-Gericke, A.; Su, D.; Schögl, R.; Yasuda, A.; Vossmeyer, T. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2003, 107, 7406-7413. [ Links ]

23. Petroski, J.; Chou, M.; Creutz, C. J. Organ. Chem. 2009, 694, 1138-1143. [ Links ]

24. Daniel, C.; Astruc, D. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 293-346. [ Links ]

25. Goddu, S.M.; Howell, R.W.; Bouchet, L.G.; Bolch, W.E.; Rao, D.V. MIRD cellular S values. Ed. Society of Nuclear Medicine, Virginia US, 1997. [ Links ]

26. Chithrani, B.D.; Ghazani, A.A.; Chan, W.C.W. Nano Lett. 2006, 6, 662-668. [ Links ]

27. Pitsillides, C.M.; Joe, E.K.; Wei, X.; Anderson, R.R.; Lin, C.P. Biophys J. 2003, 84, 4023-4032. [ Links ]

28. Elbialy, N.; Abdelhamid, M.; Youssef, T. J. Biomed. Nanotech. 2010, 6, 687-693. [ Links ]

29. Franckena, M.; van der Zee, J. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 22, 9-14. [ Links ]

30. Franckena, M.; Fatehi, D.; de Bruijne, M.; Canters, R.A.; van Norden, Y.; Mens, J.W.; van Rhoon, G.C.; van der Zee, J. Eur. J. Cancer. 2009, 45, 1969-1978. [ Links ]

31. Huang, X.; El-Sayed, I.H.; El-Sayed MA. Methods Mol. Biol.2010, 624, 343-357. [ Links ]

32. Huang, X.; Peng, X.; Wang, Y.;Shin, D.M.; El-Sayed, M.A.; Nie, S. ACS Nano. 2010, 4, 5887-5896. [ Links ]

33. Mendoza-Nava, H.; Ferro-Flores, G.; Ocampo-Garcia, B.E.; Serment-Guerrero, J.; Santos-Cuevas, C.; Jimenez-Mancilla, N.; Luna-Gutierrez, M.; Camacho-Lopez, M.A. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2013, 31, 17-22. [ Links ]

34. Chanda, N.; Kattumuri, V.; Shukla, R.; Zambre, A.; Katti, K.; Upendran, A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010, 107, 8760 8765. [ Links ]