Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Migraciones internacionales

versão On-line ISSN 2594-0279versão impressa ISSN 1665-8906

Migr. Inter vol.14 Tijuana Jan./Dez. 2023 Epub 08-Set-2023

https://doi.org/10.33679/rmi.v1i1.2568

Papers

Social Representations of Migration Among Venezuelan Immigrants Residing in Metropolitan Lima, Peru

1 Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Perú, katherine.acuna@unmsm.edu.pe

2 Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Perú, benjamin.bazan@unmsm.edu.pe

3 Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Perú, emalvaceda@usil.edu.pe,

4 Universidad Autónoma de Coahuila, México, iris.monroy@uadec.edu.mx

This article aims at understanding the social representations of migration among Venezuelan immigrants residing in Metropolitan Lima during 2018. Based on a phenomenological design, 15 in-depth interviews and a hybrid content analysis were conducted. Several emerging categories were identified, such as the motivations (primarily political and economic) for migration, and its personal, psychosocial and familial consequences. Regarding the decision-making process, the journey and limitations for emigration from Venezuela to Peru were evidenced. Finally, the study revealed an empathetic attitude among migrants, evidenced in their assistance, concern and suggestions for improving the situation of migrants. In conclusion, the social representations of migration are shaped by motivations, consequences, decision-making processes, and an empathetic attitude, all of which are influenced by the social, cultural, and political characteristics of the receiving country.

Keywords: 1. social representations; 2. migration; 3. empathetic attitude; 4. Venezuela; 5. Peru.

Se busca conocer las representaciones sociales de la migración entre inmigrantes venezolanos residentes de Lima Metropolitana durante 2018. A partir de un diseño fenomenológico, se realizaron 15 entrevistas a profundidad y un análisis de contenido híbrido. Se identificaron categorías emergentes, como los motivos (políticos y económicos) y las consecuencias de la migración a nivel personal, psicosocial y familiar. En cuanto al proceso de toma de decisiones, se evidenciaron el trayecto y las limitaciones para la emigración de Venezuela a Perú. Finalmente, se encontró una actitud empática entre los migrantes, evidenciada en la ayuda, la preocupación y las sugerencias para mejorar la situación de los migrantes. Se concluye que las representaciones sociales de la migración se articulan en motivos, consecuencias, el proceso de la toma de decisiones y la actitud empática, los cuales se ven influenciados por las características sociales, culturales y políticas del país de recepción.

Palabras clave: 1. representaciones sociales; 2. migración; 3. actitud empática; 4. Venezuela; 5. Perú.

Introduction

Mass movements of citizens have been part of Latin American history, intensifying during the 20th century especially due to political and economic reasons (Solimano, 2008). From the year 2000 onwards, new migration policies were implemented in response to border security issues and transnational links, climate phenomena, gangs, economic crises, organized crime, and the visibility of violence (Martínez et al., 2015). In recent years, Venezuelan citizens (migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers) reached “the figure of 3.7 million in the world, of which 3.0 million resided in Latin American and Caribbean countries” (Gandini et al., 2019, p. 10), especially in Colombia, Peru and Ecuador (Mazuera-Arias et al., 2019). As of November 2020, 1 043 460 million Venezuelan migrants were recorded as living in Peru (Plataforma de Coordinación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela, 2020); of these, 90% had completed the procedure to obtain their Temporary Stay Permit (PTP, acronym in Spanish for Permiso Temporal de Permanencia), a document that accredits the regular migratory status for Venezuelan migrants in Peru, allowing them to (among other things) work formally (Organización Internacional para las Migraciones [OIM], 2020; Superintendencia Nacional de Migraciones, 2019).

The political and economic crisis in Venezuela is the main cause of the current migration wave in the country (Bermúdez et al., 2018), which was aggravated by the economic sanctions imposed by the United States, such as account closures, financial restrictions, and loss of credit, among others (Camilleri & Hampson, 2018; Doocy et al., 2019; Gedan, 2017; John, 2018; Weisbrot & Sachs, 2019).

Between September and October 2018, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) (OIM, 2018) surveyed 2 148 Venezuelan nationals in Peru. Of these, 53% were male; 56% were between 18 and 26 years old; 49% were married or cohabiting; and 53% had university degrees. These belong to what Pérez (quoted in Koechlin et al., 2018) calls “the fourth migratory wave,” made up of middle/lower class people in search of better income to survive and who, according to Páez (2016), meet the characteristic of being entrepreneurs, employees and/or students. In that sense, since 2015 the flow of migrants came mainly from that socioeconomic stratum, most of them having decided to move on foot for five to seven days in order to reach Peru (Koechlin et al., 2018), which caused them physical and psychological exhaustion, this coupled with the situations of violence of which they were victims due to their status as migrants, such as theft of belongings during their journey, verbal aggression, and acts of discrimination and xenophobia (Herrera, 2020; Plan Internacional, 2019). Migrants who sought to satisfy their immediate economic needs opted for street commerce or to work without a contract in establishments, often being victims of human trafficking, specifically sexual exploitation (Blouin, 2019; OIM, 2017; Sánchez Barrenechea et al., 2020).

Venezuelan immigrants being exposed to new situations, their need to adapt to new ways of living and to cope with the problems of the receiving country, leads to consider the social representations on migration held by Venezuelan immigrants residing in Metropolitan Lima in 2018.

Social Representations

Social representations are the set of systems, values and practices used to establish a social order and to make communication possible (Moscovici, 1979); in this sense, they enable the understanding of a shared social reality. Social representations can be seen as particular modalities of knowledge, of common sense, which are acquired and modified through the social interaction of individuals; the main functions of social representations are the understanding of reality in a clear and different way from other phenomena, the guiding of actions among individuals, and of their communication in relation to the social fact represented (Araya, 2002; Martínez, 2002; Wagner et al., 2011).

The construction of social representations takes place through two processes: 1) “objectification,” when abstract concepts are transformed into concrete experiences through the processes of selective construction of elements, such as the figurative schema (which captures the essence of the phenomenon) and the naturalization of the concept in everyday images, so that what was initially abstracted becomes concrete; and 2) “the anchoring process,” which allows the integration of different elements into pre-existing frames of reference (Jodelet, 1984).

There are different approaches to the study of social representations. For the practical purposes of this paper, we will start from the processual approach (Moscovici, 1979), which analyzes social representations within psychic dynamics-the product of individual cognitive processes-and social dynamics-formed by social interaction and contextual processes-. This is based on a hermeneutic approach to social representations focused on the discourses of individuals and groups where information is analyzed in different ways (Banchs, 2000).

The areas of study of social representations can be divided into:

Information, which implies the organization of knowledge possessed by a group with respect to a social object. In this sense, emphasis is placed on the quantity and quality of information possessed by the given group, as well as on the prejudices and stereotypes that may appear in such knowledge. It is worth mentioning that group memberships and social locations mediate the available information.

Field of representation, which expresses the organization and structure-the ordering and hierarchization-of the content of the representation in a systematized manner. This field is organized according to the figurative schema constructed in the process of objectification.

Attitude, which reflects the orientation of people’s behavior: positive, negative, or neutral, comprising affective, cognitive, and behavioral parts (Banchs, 1986; Martínez, 2002; Moscovici, 1979; Perera Pérez, 2003).

Migration as a Psychosocial Phenomenon

Migration is a process in which one or more individuals move from one political-administrative delimitation to another, for a long or definitive period of time, this resulting in changes at the social, political, economic, and cultural levels, both in the country of origin and in that of destination (Reyes, 2015). Migration studies have two approaches: 1) they can have a microanalytical scope, such as case studies;1 and 2) macrotheoretical analysis, which delves into the general, historical and structural aspects of migration (Herrera, 2006).

In relation to the migratory process, Tizón (1993) points out four moments to it: preparation, the migratory act, settlement (the period from the arrival of the migrant to the receiving country until he/she manages to satisfy his/her basic needs), and integration (which is understood as the incorporation of new cultural patterns in exchange for the loss of some of his/her own customs). On the other hand, Maldonado Valera et al. (2018) point out the following vulnerability factors of migrants: the stage they are at in their life cycle, their socioeconomic condition, their familial structure, and their ethnic and migratory conditions.

As for the reasons for migration, García (2004) proposes: inevitable migration due to lack, caused by the low purchasing power of the person in his or her country of origin, few job opportunities, and lack of security; inevitable migration due to dissatisfaction resulting from economic, social, legal, or environmental uncertainty, in which the person prefers to migrate in order to obtain higher income, professional recognition, or an independent life; and optional migration, in which case the person does not feel external pressure to migrate, rather doing so out of a desire to travel, learn, or specialize professionally, and does not idealize the receiving country or criticize his or her own country too heavily.

According to León (2005), the main reasons for migration are economic and political issues, as well as labor expectations and salary advantages in the receiving country (Pedone, 2002). Likewise, according to various research, the main reasons for Venezuelans to migrate were the search for new opportunities, the economic situation and personal, legal, and political insecurity in their country (Cabrerizo & Villacieros, 2020; Castillo & Reguant, 2017; García Arias & Restrepo Pineda, 2019; Koechlin et al., 2018); while the reasons for choosing the destination country were language and cultural closeness, having family previously living there, and the possibility of obtaining employment (Castillo & Reguant, 2017).

Although migrants tend to overvalue the positive characteristics of the destination country, these are subsequently contrasted with the subject's own experiences when facing socio-labor and adaptation difficulties in their new context, given that some migrants face intense culture shock and loneliness in the receiving country based on the resources they possess (Montero Izquierdo, 2006). In addition, the cultural representation of the immigrant as someone who successfully returns to their native country exerts considerable social pressure on them (Montero Izquierdo, 2006; Castillo & Reguant, 2017).

Migrants experience different psychosocial processes as they seek to adapt to their new life in the receiving country, such as migratory mourning, migratory resilience, and the acculturation process (Berry, 1997; Alvarado, 2008; Ungar, 2013). According to Achotegui (1999), migratory mourning is the feeling of losing valuable emotional ties that have influenced the construction of the migrant’s personality (family, friends, social position, etc.), which must be then re-established in the host country. Seven migratory duels can be differentiated: 1) for family and friends, 2) for language, 3) for culture, 4) for land, 5) for status, 6) for contact with the own ethnic group, and

due to physical risks (Loizate, 2017). In this regard, the symptom cluster of extreme grief due to chronic stress caused by loneliness, the failure of the migration project, and the struggle for survival is known as the Ulysses syndrome (Achotegui, 2008).

Migrant resilience is influenced by social networks, kinship groups, community and original cultural resources (Ungar, 2013), as well as by the sense of identity towards the migrants’ original roots, collectivism, spirituality, and life satisfaction (Sajquim & Lusk, 2018). On the other hand, migrant entrepreneurship and support networks are important as a form of personal enrichment due to the interaction of migrants with other cultural patterns (Saccani, 2013; Koechlin et al., 2018; Martínez & Martínez García, 2018). Other stress coping strategies include individual mobility, distraction, recategorization, and advantageous social comparisons (Urzúa et al., 2017). In this sense, the preference for strategies that demonstrate the individual’s agency is related to the internal conflict that reduces the likelihood that migrants seek help from public entities in the receiving country, when faced with challenging situations in their acculturation process (Rihm Bianchi & Sharim Kovalskys, 2017).

The acculturation process-which consists of the adoption of elements of the receiving culture, generating changes in the behaviors and attitudes towards, and cognitions, the culture of origin (OIM, 2006)-is influenced by factors such as racial similarities, religion, the human and social capital of the parents, the matching level of the expectations and the reality of the country, and generation and context of acceptance towards the migrant (Checa & Monserrat, 2015). In this regard, Berry (1997) suggests that the migrant can express four types of attitudes towards this phenomenon:

Integration, where the migrant keeps to his or her cultural patterns, while showing interest in the culture of the receiving country, without rejecting his or her original customs;

Assimilation, where the individual shows greater affinity for the receiving culture than for his/her own;

Separation, where the individual seeks to preserve his or her traditional customs and tries to keep away from the culture of the receiving country, even rejecting it; and

Marginalization, where the individual is distant from both cultures, as he/she does not maintain his/her own customs and does not show interest in those of the receiving culture.

According to the study by Zlobina et al. (2008) conducted in Spain with immigrants from Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Morocco, Eastern Europe (Ukraine and Russia), and sub-Saharan Africa (Senegal and Cameroon), separation and integration were the strategies most commonly deployed. The findings of this study were confirmed by Lara (2017).

The effects of the migration process in the receiving country may or may not be favorable. Some examples in the economic sphere are the increase in labor competition and poverty rate, loss of jobs, decrease in wages, increase in cases of discrimination at the psychosocial level, and racism or xenophobia-due to migrants being perceived as a danger to those living in the host country, even affecting the mental health of migrants-(Mesa, 2006; Aruj, 2008; Mera et al., 2017). The perception of the migrant as an “alien other” is reinforced by the actions or omissions of the State in the receiving culture (González & Tavernelli, 2018); digital media also influence this diffusion by stereotyping and generating prejudices about migrants (Ramírez Lasso, 2018). Thus, the main objective of this research is to learn about the social representations held by Venezuelan immigrants residing in Metropolitan Lima during 2018.

Methodology

Based on a qualitative approach of phenomenological design (Creswell & Poth, 2018), and by means of in-depth interviews, we sought to understand the social representations of migration from the frame of reference of those who experience it. Fifteen Venezuelan migrants participated in the study, selected under the following criteria: that they had the Temporary Stay Permit to reside in Peru-so as to explore the phenomenon in people formalized to work-, that they were between 18 and 45 years old, and that they had resided in Peru for at least one month. Those who were not working during the interviewing season were excluded. These criteria made it possible to homogenize the participants in accordance with the chosen analysis design (Robinson, 2014). Participants were selected intentionally and by the criterion of convenience.

Of the total number of participants, 10 were women and the rest were men. They ranged in age from 19 to 41 years (with a mean of 30 years). Fifty-three percent were adults aged 30 to 41 years, and the rest were young people aged 19 to 29 years. Fifty-three percent of the participants were single. Eighty percent had some college education. Fifty-three percent had a temporary job (they sold cell phone SMS cards, were security guards, kitchen assistants, among others), and the rest were underemployed (they worked as street vendors). Participants came from the states of Apure, Aragua, Caracas, Carabobo, Miranda and Zulia, all with a medium level Human Development Index (HDI) between 2013 and 2018 (Global Data Lab, 2021). In addition, 67% had resided more than six months in Peru (Table 1). All participants were found through references provided by other informants. So as to protect their privacy, pseudonyms chosen by them were used. Currently, only two of the participants (Yolimar and Douglas) live with their children in Peru.

Table 1 Characteristics of Interviewees

| Pseudonym | Sex | Age | Marital status | Educational level | Last job in Venezuela | Current job in Peru | State of origin | Time of residence in Peru |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilmer | Man | 41 | Married | Graduate degree | University professor | Cell phone accessories salesperson | Caracas | More than 6 months |

| José David | Man | 29 | Married | Graduate degree | Businessman: IT services | Sales | Zulia | More than 6 months |

| María B. | Mujer | 31 | Casada | Graduate degree | High school teacher | Cell phone accessories salesperson | Caracas | More than 6 months |

| Xiorangel | Mujer | 23 | Single | Some college | Sales Advisor | Street vendor | Carabobo | More than 6 months |

| Samuel | Man | 24 | Soltero | Some college | Project planning | Cell phone accessories salesperson | Aragua | 1 to 6 months |

| Yosilani | Mujer | 38 | Casada | Graduate degree | Insurance Broker | Street vendor | Maracaibo | 1 to 6 months |

| María J. | Mujer | 28 | Single | Graduate degree | Accountant for a company | Street vendor | Maracaibo | More than 6 months |

| María R. | Mujer | 30 | Single | Some college | Administration | Street vendor | Caracas | 1 to 6 months |

| Yaneín P. | Mujer | 26 | Single | Some college | Corporate marketing area | Street vendor | Caracas | 1 to 6 months |

| Alex | Man | 37 | Married | Graduate degree | Custody and transportation of securities | Watchman | Caracas | More than 6 months |

| Asarí | Mujer | 34 | Single | Graduate degree | Janitor | Cook | Miranda | More than 6 months |

| Flamber | Mujer | 20 | Single | Some college | Hotel trade | Street vendor | Apure | 1 to 6 months |

| Daniela | Mujer | 19 | Single | High school | School teacher | Cell phone accessories salesperson | Caracas | More than 6 months |

| Yolimar | Mujer | 35 | Casada | Some high school | Cleaning staff | Street vendor | Carabobo | More than 6 months |

| Douglas | Man | 35 | Married | Some high school | Master builder | Construction assistant | Carabobo | More than 6 months |

Source: Own elaboration based on data provided by participants (2021).

The semi-structured in-depth interview technique was made use of to collect the information (Brinkmann, 2013). For the construction of the interview script, a categorization matrix was elaborated according to the research objectives, breaking them down into topics for their due exploration (Castillo-Montoya, 2016). In this sense, the information, the field of representation, and the attitudes towards migration were noted in the interview script (Table 2). The interview script was tested by means of a pilot interview (Martínez, 2004) with a participant, according to which the wording of the questions on the given topic was modified, including the exploration of experiences. The interviews were conducted between May and November 2018, each lasting between 45 and 60 minutes (averaging 50 minutes).

Table 2 Semi-Structured Interview Script

| Topic | Questions |

|---|---|

| Information | What do you know about the migration of Venezuelans to Peru? |

| What are the reasons for Venezuelans to emigrate to Peru? | |

| What experiences have been relied to you of Venezuelan migrants in Peru? | |

| Field of representation | What do you think about Venezuelan people migrating to Peru? |

| How do you feel about Venezuelan people migrating to Peru? | |

| Attitudes | What is your opinion regarding the migration of Venezuelans to Peru? |

| What actions are you taking in response to the migration of Venezuelans to Peru? | |

| What would you suggest in relation to the migration of Venezuelans to Peru? |

Source: Own elaboration based on the theoretical-conceptual framework.

This research was approved by the ethics committee of the Autonomous University of Mexico State (UAEMéx, acronym in Spanish for Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México).2 In terms of this, the signing of an informed consent form was accounted for, which asserted the knowledge and voluntary acceptance of the participants regarding the conditions of data handling and respect for confidentiality (Parra Domínguez & Briceño Rodríguez, 2013). No interviewees were offered any compensation or incentive for their participation. It should also be noted that all interviews were conducted one to one, and were recorded on digital audio (with the consent of the participants). They were subsequently transcribed verbatim for processing, thus contributing to the confirmability of the information collected (Mertens, 2015). These transcripts were the corpus of data for our research.

For the analysis of the information, a hybrid content study was conducted (Swain, 2018) based on what Braun and Clarke (2013) proposed in terms of thematic analysis, complemented from an abductive logic (Tavory & Timmermans, 2014) that allowed for theorization. The analysis process consisted of the following stages: 1) an a priori categorization matrix was created, containing tentative codes obtained from the theoretical corpus; 2) familiarity with the data was established from the transcription of the interviews and the generation of initial quotes; 3) inductive codes were created based on the empirical data (first coding cycle), where quotes were classified based on relevant characteristics and data was compiled for each code; 4) potential themes or categories were detected from the collated codes, and memos or notes were created to deepen the analysis;

themes were reviewed, and a semantic map and code tables (primary documents) were created so as to initiate a second coding cycle (Saldaña, 2016); 6) themes were defined and delimited from an iterative analysis based on the constant comparative method; and 7) elaboration of results, wherein what was previously obtained was described.

For the analysis process, the specialized software ATLAS.ti 9.1 was employed to carry out comparative inter-case analyses for the groups of men and women, and adults and young people. It should be noted that two of the researchers coded all the interviews, which were then reviewed and supervised by the other researchers in the aforementioned processes. Divergences in the analysis were resolved through consensus between the coders and the review team.

Finally, the tactics deployed for the construction of meaning (Miles & Huberman, 2013) were:

frequency of categories, which shows the number of quotes that correspond to each category;

theoretical density, which represents the relationships between categories; both allowed us to attest for the breadth (substantiation) and semantic depth of the concepts (Martínez, 2004), and they are also indicated in parentheses after each category; and 3) representativeness, which shows the saturation of the categories, either in the total number of participants or in at least one subgroup.

Results

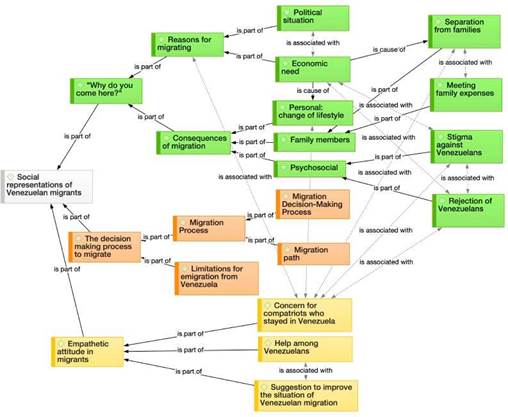

The social representations on Venezuelan migration to Peru in the eyes of those who undertake it can be divided into three emerging themes: on the one hand, the reasons to migrate and its consequences on migrants, represented in the category “Why are you here?,” followed by the decision-making process to migrate, and finally, the empathetic attitude among migrants (Figure 1).

Source: Own elaboration (2021).

Figure 1 Semantic network of social representations of Venezuelan immigration in Metropolitan Lima

“Why are you here?”: Reasons to Migrate and its Consequences on Migrants

As for the reasons to migrate, the participants pointed out economic necessity in the first place, characterized by facts such as hyperinflation, long lines to obtain food supplies, limitations in the purchase of clothing, impossibility of acquiring medicines, and problems in the supply of basic services. In this regard, it should be noted that such reasons are highly represented in the analysis of their representations.

You also don’t make enough to eat, the minimum wage is not enough for you to eat, let’s not talk about other things, but not even enough to eat, with a minimum wage you will buy a kilo of chicken and that's it, in a month (María B., personal communication, June 14, 2018).

Another reason to migrate was the political situation. The interviewees expressed their discomfort with the government, stating that it has been proven unable to deal with the economic, health and social crisis. “But one has to do these things because of this government that is killing people with hunger and everything, insecurity and all that. This is the government's fault, it is not our fault” (Asarí, personal communication, October 5, 2018).

The consequences of Venezuelan migration are evident at three levels: familial, personal and psychosocial. The consequences at the familial level involve the separation of families, and with it a sense of rupture and division, as well as of economic responsibility, which becomes a reason to assume their current position. This element was mainly pointed out by adult participants, who refer that migrants

Are risk-taking, daring people, because, hey, not everyone risks leaving their family, I at least left my children, I left my mom, I left my dad, I left everything, I left all my things there, I mean, it is not easy to emigrate (Asarí, personal communication, November 12, 2018).

Linked to this, they also pointed out that they have to pay for the expenses of their relatives in Venezuela by working in Peru, so they have to support themselves with the least possible and send the rest in remittances to their relatives. “We live in a way that we can subsist and support ourselves and our families in Venezuela. Many of us (...) will tell you the same, that we are here to work so we can help our families” (Flamber, personal communication, October 12, 2018). This factor is highly relevant for women who migrated with the purpose of sending money to their families in Venezuela.

On a personal level, the most important consequences include the change in lifestyle, which entails taking low-paying informal jobs or being subcontracted, which in turn leads to abstaining from their previous comforts, finding themselves in a country with a different culture and customs. In terms of this, it is worth mentioning that it was mostly young people who related this aspect. “Venezuelans who are professionals, who had years of experiences and had to come here to sell soda or sell [pastries], and they came from a totally different lifestyle. On top of that, it is a different culture” (Flamber, personal communication, October 12, 2018). Thus, the participants see themselves as coming from a more open culture, receptive to migrants, with other ways of getting along in the labor, affective and amicable spheres. At the same time, they relate the stereotypes or prejudices held about Venezuelan identity.

On the other hand, while they experience their change in lifestyle (especially in the workplace) as a critical situation, they perceive that such a situation is normalized in Peru.

There are coworkers who say: ‘No. They are slaves here’, [but] they are not slaves, it’s their culture. Here in Peru you work hard, here in Peru they are educated like that it’s like they

say: ‘here in Peru we do work’, they work hard (Douglas, personal communication, November 19, 2018).

At the psychosocial level, two consequences were identified: first, the stigmatization of Venezuelans, which implies the generalization of a stereotype that represents them as criminals. “Stigmatizing all [the] people who come here just because some are criminals is like saying that all Venezuelans are criminals, and that is a lie” (Wilmer, personal communication, May 15, 2018). This stereotype is associated with the second consequence, the rejection of Venezuelans by the Lima population, reflected in insults, offenses and mistreatment at work, in the street and other spaces.

“There are people [who say things] like ‘go to your country, you Venezuelan thief,’ ‘what are you doing here in Peru?’” (María R., personal communication, August 15, 2018). Both stigma and rejection were reported more frequently by women, due to vulnerability they experience (sexual harassment, human trafficking, pay differentials, precarious working conditions, and so on).

The Decision-Making Process

The decision to migrate involves the assessment of various factors; on the one hand, the migration process, which includes both the decision to migrate process and the migration journey. The decision to migrate refers to the factors that were taken into account to select Peru as a destination, influenced by the economic stability of the country, the recommendations and experiences of friends or relatives, the lack or presence of restrictions for entry at the border, as well as having the money pay for the trip; based on the above, migrants could choose a country as transitional (as Peru was for several participants) or as a final destination. This aspect was more representative among adults.

People mainly “were quite well-off” [had money] and went as far as Chile, Argentina and Panama, those countries were the most... we can say preferred, most sought after destinations; but time passed and it was much cheaper to get to Peru than to get to Chile for example, or to Argentina which is even farther away (María B., personal communication, June 14, 2018).

The migration journey describes the means of transportation used by Venezuelan migrants to reach Peru, and their difficulties, such as physical and mental fatigue, food shortages, etc. This factor was most frequently reported by young people. The route chosen was mainly by bus, due to the impossibility of affording other means. “There are people who come by road, the bus makes the trip a little more pleasant. But imagine those who come as backpackers, sometimes they arrive here without shoes after 15 days of walking” (Flamber, personal communication, October 12, 2018). In this regard, it is worth noting that this journey was more frequently related by men, which is attributed to the fact that men were more descriptive and explicit about their experience of moving to Peru; conversely, women focused more on the social and emotional reasons and consequences of migration.

The second category, called “limitations to emigrate from Venezuela,” highlights the difficulty to pay for their trip, the robberies carried out by their compatriots or the Venezuelan national guard at the border, and the difficulty in obtaining a passport (due to how long the process takes and its high cost). It should be noted that this factor is more prominent among adults in general, and men.

There are many people in Venezuela who do not have a passport, because of the situation they deny it or hide it from you, saying that it is not ready yet, that there are no materials. Now it costs good money, it costs a lot [...] and it takes you up to a year to get it, so that is also unfortunate (Alex, personal communication, October 9, 2018).

Empathetic Attitude

The attitudes related to migration collected in the interviews are divided into three categories. First, “concern for their compatriots who stayed in Venezuela,” which refers to the sadness, disappointment, and helplessness felt by the participants in view of the situation their country is going through, forcing them to emigrate to work abroad. According to the analysis carried out, it was found that this category is more highly represented among adults and women; it is estimated that the difference arises due to the management of the micropolitics of care in the home, and the traditional cultural roles of family care associated with women.

I feel sad because there were many people who, who had (...) Who were already professionals and were used to another lifestyle and then had to start from scratch, to sell whatever on the street, I imagine that they feel bad. (...) I imagine that they feel bad, with so many things achieved, obtained, and then just like that a government comes and tears your life apart (Daniela, personal communication, October 28, 2018).

Second, the category of “help among Venezuelans” frames the actions they carry out through affective, motivational, and cognitive mechanisms to support their compatriots. In this regard, migrants share their experiences about their stay and the procedures to be followed in the host country, both in the labor and legal areas, as well as emotionally. This factor was mainly reported by young people.

Of course, we advise them, we tell them, “Well, you have to do this to get your papers. Go and look for a job. Well, if you can’t get a job, well, go sell some pastries then.” So we motivate them, just as we arrived and went out to find people to guide us. We see Venezuelans arriving, and we guide them as well. There are some who despair because they can't get a job, or we see them crying on the street corners. Well, I went through that, I had that experience. [We tell them] “Be brave, go ahead,” that there are options, to sell pastries, let’s go sell some bombas, let’s look for a way to make a living (Yosilani, personal communication, September 27, 2018).

Finally, as part of an empathetic attitude towards future migrants, through the code “suggestions to improve the situation of Venezuelan migration,” various proposals and initiatives were put forward that the participants consider can help to ameliorate the problems faced by Venezuelan migrants in Peru. These strategies (aimed at both future migrants and the host country) include implementing criminal background checks at the border and speeding up legal residency procedures, campaigns and informative talks in the media urging Peruvians to avoid stereotyping Venezuelans, and finally, inviting both their compatriots and those planning to migrate to embrace Peru with its particular history, problems, customs and culture. This category was mainly reported by adults. “Well look, I consider as such that Peru should deploy information campaigns or talks aimed at Peruvians for them to get to know Venezuelans. And that they understand that this crisis is not only happening to Venezuela” (Flamber, personal communication, October 12, 2018).

It is worth mentioning that the three categories mentioned above, included within the empathetic attitude, also show the positive consequences of the migration experience. Thus, the conditions under which the migratory act unfolds lead to concern, help and suggestions for their fellow countrymen.

Discussion

This study aimed at understanding the social representations held by Venezuelan immigrants residing in Metropolitan Lima during 2018. Fifteen in-depth interviews were analyzed, the results of which allowed the construction of an intermediate-range theory (Green & Thorogood, 2004) contextualized in the analysis of the phenomenon of migration, in the specific reality of Lima, Peru, referencing the experiences of Venezuelan migrants, as well as the theoretical foundations of Moscovici (1979), León (2005), Castillo and Reguant (2017), Koechlin et al, (2018), García Arias and Restrepo Pineda (2019); and Cabrerizo and Villacieros (2020).

Regarding the information related to the migratory experience, the main reasons for migrating were referred as economic, caused by hyperinflation, shortages, and the difficulty of access to basic subsistence products. The above is complemented by the political situation endured by migrants, which is consistent with what has been pointed out by different research (Camilleri & Hampson, 2018; Doocy et al., 2019; Gedan, 2017; John, 2018; Weisbrot & Sachs, 2019; Cabrerizo & Villacieros, 2020). This allows us to categorize this phenomenon as a migration due to lack and, above all, dissatisfaction (García, 2004). Therefore, not only do people migrate to improve their quality of life, but, in this case, deprivation and extreme dissatisfaction are the main mediators of this desire to migrate. All this (linked to the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, belonging to a fourth wave of migration who, as indicated above, are mostly young, with university degrees, and of middle-class stratum) allows us to hypothesize that the loss of their class privileges, a product of the economic crisis, forced and motivated them to migrate, which has also been pointed out by Gedan (2017), and Camilleri and Hampson (2018).

On the other hand, the consequences of migration are evident at different levels. At the familiar level, separation is experienced; evidence suggests that separation has implications for the migrant’s health, such as experiencing loneliness, as stated by Montero Izquierdo (2006), or the likelihood of developing high levels of stress, as reported by Urzúa et al. (2018). Similarly, there is evidence of the possibility of supporting their family’s expenses in Venezuela, which is associated with the perception of Peru as a transition country and not a destination, where migrants could continue their studies, validate their degrees, and therefore get better jobs, which has been previously pointed out by other studies (Castillo & Reguant, 2017; García Arias & Restrepo Pineda, 2019). This is similar to the case in which migrants from the Northern Triangle of Central America see Mexico as a transit country into the United States, their final destination.

On a personal level, the change in lifestyle is consistent with the migrants’ adaptation to their new context and socio-labor difficulties. Thus, they move between informal jobs, underemployment, unemployment, and their assimilation to Peruvian culture, in parallel to the emotional pain of leaving behind plans and projects, family and housing, as referred to by Montero Izquierdo (2006).

At the psychosocial level, it is agreed with Mera et al. (2017) that migration brought socio- cognitive and cultural changes for migrants and residents of the receiving country. On the other hand, it was observed that the matching level between expectations and the reality of the host country, the generation to which the migrant belongs, and having access to social support, influence the choice of the acculturation strategy that the migrant will opt for, as referred by Checa and Monserrat (2015). Another of the psychosocial consequences is the stigma and rejection imposed on Venezuelan migrants due to the lack of formal and immediate recognition by the host country. It should be noted that this situation has also been reported in other studies (González & Tavernelli, 2018; Blouin, 2019).

Regarding the decision-making process to migrate (consistent with the field of representation), correspondence was observed between what was indicated in the decision-making process to migrate and what was found by Pedone (2002), since both the economic situation of the migrant and the socio-labor conditions of the destination country play an important role when choosing the country migrants will select to reside in. The migratory journey that the participants undertook (despite the physical and emotional repercussions) is consistent with that described by Koechlin et al. (2018), and Tizón and Salamero (1993). Likewise, the limitations for emigration from Venezuela demonstrate the different barriers or difficulties that the interviewees had to face in order to leave their country (such as overcoming official and unofficial controls, which consisted of checking belongings and paying money), this becoming a stressor for Venezuelan migrants, as stated by Cabrerizo and Villacieros (2020), Herrera (2020), and Plan Internacional (2019).

When it comes to the empathetic attitudes of migrants, the category of concern for their compatriots shows an empathetic attitude towards making changes for the common good of Venezuelan migrants, thus improving their quality of life. The source of this empathy is the fact of being affected by the same political-economic causes in their country, and the consequences that these brought about within the migration process. This is consistent with the findings of Saccani (2013), who refers that affective support is intended to avoid uprooting and maladjustment in the face of the new condition as a migrant.

The above is related to the category of “help among Venezuelans,” which is consistent with Koechlin et al. (2018) and Sajquim and Lusk (2018), who evidenced that the need for support networks, added to the cultural collectiveness characteristic of Venezuelans, generate informal groupings wherein migrants share their experiences in the host country and seek advice on procedures, job opportunities, or emotional support to counteract the effects of migratory grief. Both categories are related to social support among Venezuelan migrants, a strategy that allows them to cope with their new lifestyle (Cabrerizo & Villacieros, 2020).

Regarding the suggestions proposed to improve the situation of Venezuelan migration, these match with what was found by Blouin (2019): that Venezuelan migrants propose speeding up the processing of legal documents, the validation of their documents, and making the requirements for accessing job opportunities more flexible, as well as greater control and restrictions for entry at the border.

The participants reported being in the process of assimilating into the culture of the host country and accepting that they would not have the same living conditions as in their country of origin. This culture shock, taking into account that these are people from areas with medium HDI (Global Data Lab, 2021), results in differences between the migrant's expectations and the reality of the host country, this supporting what Checa and Monserrat (2015) already pointed out. Even with all this, migrants still accept these new lifestyles because they know these are better conditions than what their country can offer them at that moment.

The main strength of this research is that it allowed us to evidence the motivations and consequences of migration in the lives of migrants, followed by the process and limitations to migrate, as well as the empathetic attitude among compatriots. On the other hand, distinctive elements were also evidenced in terms of gender, where men in their narratives prioritized the migratory journey and the limitations to emigrate from Venezuela, while women prioritized the concern to pay for the expenses of their relatives in their country of origin, the causes and emotional consequences of migrating, and perceived with greater intensity the stigma and rejection faced by their compatriots, stating having greater concern for them. On the other hand, the adults mainly mentioned the consequences at the familial level, as well as the process of deciding to migrate, and the limitations to emigrate from Venezuela; while young people pointed out the change of lifestyle, the migratory journey, and the help provided by Venezuelans among themselves.

The limitations that stood out the most were the little availability of the participants to be interviewed, due to the fact that they were working most of the day, although this did not affect the questions asked, nor the number of people interviewed. On the other hand, there was a limitation in terms of the sex of the participants, more women than men having been interviewed. Finally, selecting only participants with PTP left out the experiences of people in more precarious situations.

Conclusions

The social representations held by Venezuelan immigrants about their migration to Peru are based on the reasons they have for leaving their country, economic necessity and the political situation being the most representative factors. Migration impacts the familial, personal and psychosocial levels.

Within the personal level, the decisions and/or motivations to migrate are framed as axes or starting points. On the other hand, with regard to the limitations for emigration from Venezuela, the administrative procedures stand out, and with them the bureaucratic and political barriers migrants have to face.

Finally, an empathetic attitude was observed among migrants, evident in the help, concern and suggestions for and towards their compatriots, who, like the participants were, are affected by similar causes in the migration process. This is manifested in affective support, support networks, and the collective nuance that the migratory experience acquires.

One of the main contributions of this study lies in its description of the social representations of migration to Peru, based on the discourses of immigrants themselves, especially with regard to decision-making processes and their empathetic attitude towards their fellow countrymen and women, which allowed us to understand these social representations beyond the merely cognitive, and to make visible the affective element present in the process.

Translation: Fernando Llanas.

Referencias

Achotegui, J. (1999). Los duelos de la migración: una perspectiva psicopatológica y psicosocial. En E. Perdiguero y J. Comelles (Edits.), Medicina y cultura (pp. 88-100). Bellaterra. [ Links ]

Achotegui, J. (2008). Duelo migratorio extremo: el síndrome del inmigrante con estrés crónico y múltiple (Síndrome de Ulises). Psicopatología y Salud Mental, (11), 15-5. [ Links ]

Alvarado, R. (2008). Salud mental en inmigrantes. Revista Chilena de Salud Pública, 12(1), 37-41. [ Links ]

Araya, S. (2002). Las representaciones sociales. Ejes teóricos para su discusión (Cuadernos de Ciencias Sociales, núm. 127). Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO). [ Links ]

Aruj, R. S. (2008). Causas, consecuencias, efectos e impacto de las migraciones en Latinoamérica. Papeles de Población, 14(55), 95-116. [ Links ]

Banchs, M. A. (1986). Concepto de representaciones sociales: análisis comparativo. Revista Costarricense de Psicología, 8-9, 27-40. [ Links ]

Banchs, M. A. (2000). Aproximaciones Procesuales y Estructurales al estudio de las Representaciones Sociales. Papers on Social Representations, 9, 3.1-3.15. [ Links ]

Bermúdez, Y., Mazuera-Arias, R., Albornoz-Arias, N., y Morffe Peraza, M. A. (2018). Informe sobre la movilidad humana venezolana. Realidades y perspectivas de quienes emigran (9 abril al 6 de mayo de 2018). Servicio Jesuita a Refugiados. [ Links ]

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 46(1), 5-34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x [ Links ]

Blouin, C. (Coord.). (2019). Estudio sobre el perfil socio económico de la población venezolana y sus comunidades de acogida: una mirada hacia la inclusión. Instituto de Democracia y Derechos Humanos de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú y PADF. [ Links ]

Braun, V., y Clarke, V. (2013). Successful Qualitative Research. A Practical Guide for Beginners. Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Brinkmann, S. (2013). Qualitative Interviewing. Understanding qualitative research. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Cabrerizo, P. y Villacieros, I. (2020). Trayectorias migratorias de refugiados y solicitantes de asilo de Venezuela: un análisis desde la perspectiva del estrés. En C. Blouin (Coord.), Después de la llegada: realidades de la migración venezolana (pp. 195-210). Idehpucp/Themis. [ Links ]

Camilleri, M., y Hampson, F. (2018). No Strangers at the Gate: Collective Responsibility and a Region’s Response to the Venezuelan Refugee and Migration Crisis. Centre for International Governance Innovation. [ Links ]

Castillo, T., y Reguant, M. (2017). Percepciones sobre la migración venezolana: causas, España como destino, expectativas de retorno. Migraciones. Revista del Instituto Universitario de Estudios Sobre Migraciones, (41), 133-163. https://doi.org/10.14422/mig.i41.y2017.006 [ Links ]

Castillo-Montoya, M. (2016). Preparing for Interview Research: The Interview Protocol Refinement Framework. The Qualitative Report (TQR), 21(5), 811-831. [ Links ]

Checa, J. C., y Monserrat, M. (2015). La integración social de los hijos de inmigrantes africanos, europeos del este y latinoamericanos: un estudio de caso en España. Universitas Psychologica, 14(2), 475-486. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy14-2.lish [ Links ]

Creswell, J. W., y Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Doocy, S., Page, K. R., de la Hoz, F., Spiegel, P., y Beyrer, C. (2019). Venezuelan Migration and the Border Health Crisis in Colombia and Brazil. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 7(3), 79- 91. https://doi.org/10.1177/2331502419860138 [ Links ]

Gandini, L., Lozano Asencio, F., y Prieto, V. (Coords.). (2019). Crisis y migración de población venezolana. Entre la desprotección y la seguridad jurídica en Latinoamérica. UNAM. [ Links ]

García, P. (2004). La migración de argentinos y ecuatorianos a España: representaciones sociales que condicionaron la migración. Amérique Latine. Histoire et Mémoire, (9). https://doi.org/10.4000/ALHIM.399 [ Links ]

García Arias, M. F., y Restrepo Pineda, J. E. (2019). Aproximación al proceso migratorio venezolano en el siglo XXI. Hallazgos, 16(32), 63-82. https://doi.org/10.15332/2422409x.5000 [ Links ]

Gedan, B. N. (2017). Venezuelan Migration: Is the Western Hemisphere Prepared for a Refugee Crisis? SAIS Review of International Affairs, 37(2), 57-64. https://doi.org/10.1353/sais.2017.0027 [ Links ]

Global Data Lab. (2021). Human Development Indices (5.0). Radboud University. https://globaldatalab.org/shdi/shdi/VEN/ [ Links ]

González, A., y Tavernelli, R. (2018). Leyes migratorias y representaciones sociales: el caso argentino. Autoctonía. Revista de Ciencias Sociales e Historia, 2(1), 74-91. https://doi.org/10.23854/autoc.v2i1.49 [ Links ]

Green, J., y Thorogood, N. (2004). Qualitative Methods for Health Research. Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Herrera, G. (Coord.). (2020). Voces y experiencias de la niñez y adolescencia venezolana migrante en Brasil, Colombia, Ecuador y Perú. CLACSO. [ Links ]

Herrera, R. (2006). La perspectiva teórica en el estudio de las migraciones. Siglo XXI Editores. [ Links ]

Jodelet, D. (1984). La representación social: fenómenos, conceptos y teoría. En S. Moscovici (Ed.), Psicología social II. Pensamiento y vida social (pp. 494-505). Paidós. [ Links ]

John, M. (2018). Venezuelan economic crisis: crossing Latin American and Caribbean borders. Migration and Development, 8(3), 437-447. https://doi.org/10.1080/21632324.2018.1502003 [ Links ]

Koechlin, J., Vega, E., y Solórzano, X. (2018). Migración venezolana al Perú: proyectos migratorios y respuesta del Estado. En J. Koechlin y J. Eguren (Edits.), El éxodo venezolano: entre el exilio y la emigración (pp. 47-96). Universidad Antonio Ruiz de Montoya/Konrad Adenauer Stiftung e.V./Organización Internacional para las Migraciones/Observatorio Iberoamericano sobre Movilidad Humana, Migraciones y Desarrollo (OBIMID) [ Links ]

Lara, L. (2017). Adolescentes latinoamericanos en España: Aculturación, autonomía conductual, conflictos familiares y bienestar subjetivo. Universitas Psychologica, 16(2), 26-36. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy16-2.alea [ Links ]

León, A. M. (2005). Teorías y conceptos asociados al estudio de las migraciones internacionales. Trabajo Social, (7), 59-76. [ Links ]

Loizate, J. A. (2017). El síndrome del inmigrante con estrés crónico y múltiple (síndrome de Ulises). Revista de Menorca, 96, 103-111. [ Links ]

Maldonado Valera, C., Martínez Pizarro, J., y Martínez, R. (2018). Protección social y migración. Una mirada desde las vulnerabilidades a lo largo del ciclo de la migración y de la vida de las personas. CEPAL. [ Links ]

Martínez, G., Cobo, S., y Narváez, J. (2015). Trazando rutas de la migración de tránsito irregular o no documentada por México. Perfiles Latinoamericanos, 23(45), 127-155. https://doi.org/10.18504/pl2345-127-2015 [ Links ]

Martínez, M., y Martínez García, J. (2018). Procesos migratorios e intervención psicosocial. Papeles Del Psicólogo, 39(2), 96-103. https://doi.org/10.23923/pap.psicol2018.2865 [ Links ]

Martínez, M. (2004). Ciencia y arte en la metodología cualitativa. Trillas Editorial. [ Links ]

Martínez, M. M. (2002). La teoría de las representaciones sociales de Serge Moscovici. Athenea Digital. Revista de Pensamiento e Investigación Social, (2). https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/athenead/v1n2.55 [ Links ]

Mazuera-Arias, R. (Coord.), Albornoz-Arias, N., Morffe Peraza, M. Á., Ramírez-Martínez, C., y Carreño-Paredes, M.-T. (2019). Informe sobre la movilidad humana venezolana II. Realidades y expectativas de quienes emigran (8 de abril al 5 de mayo de 2019). SJR (Venezuela)/Centro Gumilla/UCAT/IIES-UCAB. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12442/4621 [ Links ]

Mera, M. J., Martínez-Zelaya, G., Bilbao, M. A., y Garrido, A. (2017). Chilenos ante la inmigración: un estudio de las relaciones entre orientaciones de aculturación, percepción de amenaza y bienestar social en el Gran Concepción. Universitas Psychologica, 16(5), 33-46. https://doi.org/10.11144/javeriana.upsy16-5.cier [ Links ]

Mertens, D. (2015). Research and Evaluation in Education and Psychology: Integrating Diversity With Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methods. Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Mesa, R. E. (2006). El trabajo en exclusión social de médicos del mundo: inmigrantes. Trabajo Social Hoy, (2), 61-82. [ Links ]

Miles, M. B., y Huberman, A. M. (2013). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Montero Izquierdo, G. (2006). Las representaciones sociales de los emigrantes ecuatorianos en España sobre el proceso migratorio. Alternativas. Cuadernos de Trabajo Social, 14, 35-48. https://doi.org/10.14198/altern2006.14.3 [ Links ]

Moscovici, S. (1979). El psicoanálisis, su imagen y su público. Huemul. [ Links ]

Organización Internacional para las Migraciones (OIM). (2006). Glosario sobre migración. OIM. [ Links ]

Organización Internacional para las Migraciones (OIM). (2017). Matriz de seguimiento de desplazamiento (DTM)-OIM Perú Ronda 1 (octubre-noviembre 2017). OIM. [ Links ]

Organización Internacional para las Migraciones (OIM). (2018). Matriz de seguimiento de desplazamiento (DTM)-OIM Perú, Ronda 2 (diciembre 2017-enero 2018). OIM. [ Links ]

Organización Internacional para las Migraciones (OIM). (2020). Monitoreo de flujo la población venezolana en el Perú-DTM Reporte 7. OIM. Autor. [ Links ]

Páez, T. (Coord.). (2016). La voz de la diáspora venezolana. El Estilete. [ Links ]

Parra Domínguez, M. y Briceño Rodríguez, I. (2013). Aspectos éticos en la investigación cualitativa. Revista de Enfermería Neurológica, 12(3), 118-121. https://doi.org/10.37976/enfermeria.v12i3.167 [ Links ]

Pedone, C. (2002). Las representaciones sociales en torno a la inmigración ecuatoriana a España. Íconos. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, (14), 56-66. https://doi.org/10.17141/iconos.14.2002.584 [ Links ]

Perera Pérez, M. (2003). A propósito de las representaciones sociales: apuntes teóricos, trayectoria y actualidad. CD Caudales. CIPS. [ Links ]

Plan Internacional. (2019). Crisis migratoria venezolana, una crisis de protección. Plan Internacional. [ Links ]

Plataforma de Coordinación para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela. (2020). Evolución de las cifras en los 17 países R4V (noviembre, 2020). https://www.r4v.info/es/refugiadosymigrantes [ Links ]

Ramírez Lasso, L. M. (2018). Representaciones discursivas de las migrantes venezolanas en medios digitales. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios del Discurso, 18(2), 43-58. [ Links ]

Reyes, J. U. (2015). Evolución histórica de la Migración Internacional Contemporánea. Universidad Iberoamericana. [ Links ]

Rihm Bianchi, A. y Sharim Kovalskys, D. (2017). Migrantes colombianos en Chile: tensiones y oportunidades en la articulación de una historia personal. Universitas Psychologica, 16(5), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.11144/javeriana.upsy16-5.mcto [ Links ]

Robinson, O. C. (2014). Sampling in Interview-Based Qualitative Research: A Theoretical and Practical Guide. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 11(1), 25-41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2013.801543 [ Links ]

Saccani, R. C. (2013). Redes de apoyo social en contexto migratorio: decisión de emigrar, adaptación y mercado laboral: argentinos en Málaga (2005-2009) [Tesis de licenciatura]. Universidad Nacional de La Plata. [ Links ]

Sajquim, M. y Lusk, M. (2018). Factors promoting resilience among Mexican immigrant women in the United States: applying a positive deviance approach. Estudios Fronterizos, 19. https://doi.org/10.21670/ref.1805005 [ Links ]

Saldaña, J. (2016). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Sánchez Barrenechea, J., Blouin, C., Minaya Rojas, L. V. y Benites Alvarado, A. B. (2020). Las mujeres migrantes y refugiadas venezolanas y su inserción en el mercado laboral peruano: dificultades, expectativas y potencialidades. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. [ Links ]

Solimano, A. (Ed.). (2008). Migraciones internacionales en América Latina: booms, crisis y desarrollo. FCE. [ Links ]

Superintendencia Nacional de Migraciones. (2019). Solidaridad con acciones concretas, Revista Migraciones, (002), 2-3. https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/1274000/Revista%20Migraciones%20-%20Septiembre.pdf [ Links ]

Swain, J. (2018). A Hybrid Approach to Thematic Analysis in Qualitative Research: Using a Practical Example. Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526435477 [ Links ]

Tavory, I. y Timmermans, S. (2014). Abductive analysis: theorizing qualitative research. The University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Tizón, J. L. y Salamero, M. (1993). Migraciones y salud mental: un análisis psicopatológico tomando como punto de partida la inmigración asalariada a Catalunya. Promociones y Publicaciones Universitarias. [ Links ]

Ungar, M. (2013). Resilience, Trauma, Context, and Culture. Trauma, violence, and abuse, 14(3), 255-266. [ Links ]

Urzúa, A., Basabe, N., Pizarro, J. J. y Ferrer, R. (2017). Afrontamiento del estrés por aculturación: inmigrantes latinos en Chile. Universitas Psychologica, 16(5), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy16-5.aeai [ Links ]

Wagner, W., Hayes, N. y Flores Palacios, F. (Edits.). (2011). El discurso de lo cotidiano y el sentido común. La teoría de las representaciones sociales. Anthropos. [ Links ]

Weisbrot, M. y Sachs, J. (2019). Sanciones económicas como castigo colectivo: El caso de Venezuela. Center for Economic and Policy Research. [ Links ]

Zlobina, A., Basabe, N. y Páez, D. (2008). Las estrategias de aculturación de los inmigrantes: su significado psicológico. Revista de Psicología Social, 23(2), 143-150. https://doi.org/10.1174/021347408784135760 [ Links ]

Received: March 02, 2021; Accepted: February 21, 2022

texto em

texto em