Introduction

The face of Canada has changed over the past several decades, and immigration from all over the world has been a contributing factor. Members of more than 200 ethnicities now call Canada their home (Statistics Canada, 2016), and roughly 300 000 immigrants arrive yearly. Immigrants can be a vital force in closing the demand gap in the labour force when a native citizen population is rapidly aging and has declining birth rates. In the Canadian context, realizing the full potential of this immigrant force will require that immigrants successfully integrate into Canadian society by ensuring access to affordable housing, a welcoming community environment, education and employment opportunities, an acceptable level of income, and social inclusion (Kaushik & Drolet, 2018; Kilbride, 2014; Lysenko & Wang, 2018; Vézina & Houle, 2017).

In the past, Canadian immigration policies tended to favour selected ethnicities. Before the 1960s, most immigrants to Canada came from Europe, but immigration selection policies were later modified to eliminate discrimination based on race or national origin (Iacovetta, Draper, & Ventresca, 1997; Teixeira, Li, & Kobayashi, 2012). By the 1990s, policymakers became aware of how having a diverse immigrant workforce contributes positively to the economy: a functioning society needs a contributing labour force with a wide range of skills, educational attainment, prior work experience, and inter-cultural skills that can be adapted to different geographic regions (Hou & Picot, 2016).

Recent immigration policies are configured to give preference to those with higher levels of so- called human capital factors. From 2011-2016, most immigrants came from the Philippines, China, India, and, more recently, from Latin America, including Mexico (Statistics Canada, 2017). Around 130 000 people of Mexican origin reside in Canada (63 000 of whom were born in Mexico) (Statistics Canada, 2016). Most immigrants tend to settle in larger metropolitan areas such as Toronto, Vancouver, and Montreal (Drolet & Robertson, 2011; Fong & Berry, 2017; King, 2009; Qadeer, 2016). In these major urban areas, and their suburbs, concentrations of racialized minorities (e.g., visible minorities) have increased in size and number. Simultaneously, the suburbanization of immigrants has continued apace (Kobayashi & Preston, 2020).

In 2016, Canada relaxed the visa requirements for Mexican travelers, leading to increasing numbers of Mexican asylum seekers and those overstaying their tourist visas. Within three months, more than 72 000 Mexicans entered Canada from Mexico or the United States (Bell, 2018; Chapman, 2017; Mehler Paperny, 2017; Samuels, 2017). Many coming from the United States felt they needed to leave the country as the Donald Trump presidency began. Overall, while the United States has historically received the largest number of Mexican immigrants, a new migration pattern has recently emerged between Mexico and Canada (Mehler Paperny, 2017; Perkel, 2017).

Vancouver, British Columbia, is a highly attractive destination and port of entry for immigrants. It provides high and low-skilled job opportunities in different sectors of the economy. Due to its affordable housing problems, many immigrants settle in the suburbs. These suburbs can serve as important ‘social laboratories’ (Hiebert, 2015; Tood, 2019; Qadeer, 2016) as immigrants ‘ethnically refashion’ the areas (Teixeira, 2017). The experiences, narratives, and decision-making patterns of new immigrants provide scholars in the urban planning, geography, and immigration fields with an excellent research opportunity. The suburbanization of immigration can yield rich data about the barriers and facilitators related to settlement, housing experiences, and integration.

When settling in a new country, many recently arrived immigrants prefer to live near others who speak their language. In Vancouver, many settled and concentrated in specific suburban neighbourhoods due to lower housing costs. They may also be under-employed relative to their education and experience (Lysenko & Wang, 2015; Pendakur & Pendakur, 2015). As a result, they are more likely to be restricted to lower-quality housing in neighbourhoods characterized by poverty and socio-spatial polarization (Ghosh, 2015; Grant, Walks, & Ramos, 2020; Ley & Lynch, 2020; Younglai & Wang, 2019).

Other immigrants, particularly those who are highly skilled, may arrive in Canada with a good knowledge of English or French. They may be willing to pay higher than market rent to obtain desirable housing to fit their class expectations; this further drives up rent prices. Over time, these diverse housing needs have shifted the real estate market and the landscape of major metropolitan areas and suburbs (Carter & Vitiello, 2012; Teixeira, 2014). This kind of diversity also means that service providers and policymakers cannot design ‘one size fits all’ programs to successfully integrate all immigrants into Canadian society (Alba, Logan, Stults, Marzan, & Zhang, 1999; Bunting, Walks, & Filion, 2004; Kilbride & Webber, 2006; Lo, Shalaby, & Alshalalfah, 2011; Murdie & Skop, 2012; Singer, Hardwick, & Brettell, 2008).

Throughout Canada, major cities and suburbs are being affected by significant demographic, socio-economic, and cultural changes. Immigration is leading to huge changes in residential mobility patterns and housing preferences (Hiebert, 2015; Kataure & Walton-Roberts, 2015; Moos & Skaburskis, 2010).

Vancouver has the most expensive real estate in Canada (Schmunk, 2019), and recent low- income immigrants and refugees settling in the city face linguistic, cultural, and ethnic challenges in finding housing. These challenges are exacerbated by their lack of economic opportunities and knowledge about public assistance programs (Teixeira, 2017; Teixeira & Li, 2015). With little or no monetary resources, they are often forced to live in substandard, poorly maintained, and crowded housing conditions with family, friends, or others with similar ethnicities (Hiebert, 2015; Fiedler, Hyndman, & Schuurman, 2006; Teixeira & Li, 2015; Teixeira, 2017).

In general, Canadian suburban areas are known to be poorly equipped to serve the physical and social needs of their rapidly growing and increasingly diversifying population (August & Walks, 2018; Novac, Darden, Hulchanski, & Seguin, 2004; Teixeira & Li, 2015). However, very few studies have explored specific settlement and integration experiences of Mexican immigrants in Canadian suburbs. This study addresses this research gap by examining the settlement of Mexican immigrants in three fast-growing suburban municipalities of Vancouver: Burnaby, Surrey, and Abbotsford. The housing crisis affecting these suburban cities of Vancouver-due to a limited supply of affordable rental housing and rising high housing costs-makes these three cities challenging regions of Vancouver for new immigrants (Ley & Lynch, 2020). Following a review of the literature and description of the methods used in this study, the results section explores the Mexican immigrant settlement in the suburbs and housing recommendations by key informants. A final summary concludes with suggestions for further research.

Literature review

Housing and Immigrants

Most immigrants to Canada, regardless of country of origin, ethnicity, or economic status, settle in major urban areas (Hiebert, 2009; Hou & Picot, 2016; Murdie & Skop, 2012). This has led to a marked demographic shift in the social and economic diversity of Canada’s urban areas and their suburbs, contributing to more demand for housing (Carter & Vitiello, 2012; Depner & Teixeira, 2012; Gordon, 2020; Grigoryeva & Ley, 2019; Hiebert, Mendez, & Wyly, 2008; Moos & Skaburskis, 2010). Access to affordable housing is one of the most important contributing factors to immigrants’ social, political, and economic integration in the receiving country. Other factors include income and steady employment, access to educational opportunities, and civic integration and public engagement (Hiebert, 2015; Moos & Skaburskis, 2010).

Research findings on the success of immigrants’ integration into Canadian society are mixed. Some studies have found that many immigrants and refugees can better their situation by increasing their income and moving to better housing conditions, sometimes even progressing to home ownership (Hiebert, 2015). Others have found that immigrants are more likely to remain renters than to become homeowners and that their income levels tend to decline over time (Carter & Vitiello, 2012; Fong & Berry, 2017). Several studies have reported that immigrants have higher levels of ‘core needs’ (a composite measure of adequacy, suitability, and affordability). In comparison to non-immigrants, racial minorities immigrants (e.g., those from African, Caribbean, and Latin American countries) are more likely to have an ‘acute housing need’ in expensive housing markets such as Toronto or Vancouver (Carter & Vitiello, 2012; Diaz McConnell & Redstone Akresh, 2008). Overall, the diversity among immigrants means that there is no such thing as a ‘typical’ experience related to housing (Carter & Vitiello, 2012). However, access to affordable housing remains the biggest barrier (Hiebert, 2009; Leone & Carroll, 2010; Murdie & Skop, 2012), and this is compounded by factors including racism and discrimination (Fong & Berry, 2017).

Immigrants to Canada have varying educational and work experiences, which is reflected in housing demand (Carter & Vitiello, 2012; Murdie & Skop, 2012). For example, those who are middle class, including immigrant entrepreneurs, generally have certain levels of income and are more likely to have the resources to purchase high-priced urban or suburban homes (Kataure & Walton-Roberts, 2015). Others may take low-paying jobs despite being overqualified (Lysenko & Wang, 2015), while low-income refugees and minorities, as well as those from poorer countries, may be left with no option but to live in low-quality housing in high-poverty neighbourhoods. Still, others may choose to avoid living there by straining their income such that they cannot accumulate any savings or may get into debt, either with institutions or support systems within their ethnic- social networks. These patterns further the class and race segregation that already exists in Canadian society (Carter & Vitiello, 2012; Ghosh, 2015; Francis & Hiebert, 2014; Grant, Walks, & Ramos, 2020; Ley, 2010; Ley & Lynch, 2020; Murdie & Skop, 2012; Walks & Bourne, 2006).

Some recent public programs and initiatives by non-profit advocacy and human rights groups have tried to foster integration and diversity, but immigrants in Canada continue to face discrimination based on skin colour, ethnicity, race, religion, and national origin (Mensah & Williams, 2017; Ray & Preston, 2009; Teixeira & Li, 2015). Demand for social services like affordable housing and settlement services far exceeds the supply (Moos & Skaburskis, 2010). Additionally, tight labour and housing markets contribute to the risk of being marginalized or excluded from affordable housing and becoming poor and homeless (Bunting et al., 2004; Leone & Carroll, 2010).

The Changing Suburbs of Vancouver

Since the 1990s, immigrants have settled in cities outside urban centres (Broadway, 2000; Abu- Laban & Garber, 2005), changing the historic patterns of immigrant settlement (Murdie & Skop, 2012; Qadeer, 2016). Metropolitan areas, including Toronto, Vancouver, and Montreal, are undergoing changes such as inner-city gentrification, job suburbanization, and increasing immigrant diversity contributing to the suburbanization of the immigrant social landscape (August & Walks, 2018; Fong & Berry, 2017; Hiebert, 2015; Moos & Skaburskis, 2010).

Vancouver and Toronto have the most expensive housing markets in Canada, making housing less affordable for recently arrived immigrants and leading to more segregation, poverty levels, ‘forced’ relocations, and especially suburbanization (Murdie & Skop, 2012; Teixeira & Li, 2015). Recent immigrants and refugees are increasingly settling and concentrating in specific suburban neighbourhoods (Abu-Laban & Garber, 2005; Alba et al., 1999; Fiedler et al., 2006; Murdie & Skop, 2012; Qadeer, 2016).

Burnaby, Surrey, and Abbotsford are considered important destinations for recent immigrants and this trend is expected to continue (City of Abbotsford, 2017; City of Surrey, 2017; Teixeira, 2017). Most of the homes in these Vancouver suburbs were built after 1971 and are expensive detached owner-occupied dwellings: more than two-thirds of residents in Burnaby, Surrey, and Abbotsford are homeowners (62% in Burnaby, 69% in Abbotsford, and 71% in Surrey). These rates are higher than in the City of Vancouver (47%) but similar to the provincial average (68%). In 2016, the average price of a home in Burnaby (961 174 Canadian dollars [CAD]) was higher than that in Surrey (757 863 CAD) or Abbotsford (516 858 CAD). However, it is much lower than in the City of Vancouver (1 414 191 CAD) (Statistics Canada, 2016). In the same year, the average monthly cost for rent was 1 171 CAD in Burnaby, 1 049 CAD in Surrey, and 968 CAD in Abbotsford (Statistics Canada, 2016). About one-third of renters (37.4% in Surrey and 38.5% in Abbotsford) spent 30% or more of their income on housing. In comparison to 24.5% of homeowners in Surrey and 18.8% of homeowners in Abbotsford. Burnaby is an exception: the high cost of housing means that 45% of homeowners pay more than 30% of their income on housing, compared with 28.7% of renters (Statistics Canada, 2016).

In most cities, immigrants with assets and high incomes can afford expensive detached houses. These populations include some Chinese in the suburbs of Vancouver (Richmond) or the periphery of Metro Toronto (Markham) and some South Asians in the City of Brampton (Kataure & Walton- Roberts, 2015; Qadeer, 2016). However, some refugees and low-income immigrant groups often share a housing unit with other families, such as Tamils living in the suburbs of Toronto (Ghosh, 2015). As a result, suburbs have become a mix of wealthy immigrants living in expensive detached homes as well as little pockets of poverty where some refugees, rent-stressed families, and low- income immigrants coexist with the homeless (Bunting et al., 2004; Gordon, 2020; Kobayashi & Preston, 2020; Ley & Lynch, 2020; Simich, Beiser, Stewart, & Mwakarimba, 2005).

These recent trends have countered the traditional assumption that immigrants begin their lives in Canada in inner-city neighbourhoods (Murdie & Skop, 2012). However, very few studies have investigated the geographic and social dimensions of this relatively new phenomenon. Bunting et al. (2004) found that newer (outer) suburbs (of Vancouver) are more likely to bar low-income residents. They noted that “housing in-affordability stress in the outer suburbs has been produced by hugely inflated housing markets that occurred in the 1980s when demand for housing far exceeded the supply that could be built” (p. 386).

Vancouver is a good example and helps illustrate how the housing crisis is a vicious cycle: rent- stressed households save less of their wages for other expenditures; less spending slows the economy, leading to wage freeze (Teixeira, 2014). Over time, the concentrations of poverty in affluent suburbs and more rent-stressed immigrant households have led to calls for better policies to prevent this trend. Effective policies will require understanding how immigrant renters integrate into Canadian society, their experiences, and narratives of how they navigate this path and why certain groups are more successful than others (Hulchanski, 2010). The subsequent section focuses specifically on Mexican immigrants.

Mexican Immigrants in Canada

Approximately half a million Latin Americans live in Canada. Most of them are from Mexico, Colombia, El Salvador, Peru, Chile, Venezuela, and Argentina (Armony, 2015). Currently, about 70 000 Latin Americans live in British Columbia, and about 23 000 are Mexicans of ethnic origin (Redacción NM, 2016; Statistics Canada, 2016).

In 2016, about 125 000 individuals of Mexican ethnic origin lived in Canada, mostly in Toronto, Vancouver, Montreal, Ottawa, Calgary, and Edmonton. This population is increasing rapidly in Canada, as is the number of Mexican-born immigrants.

Mexican Immigrants in British Columbia and the Suburbs of Vancouver

The Greater Vancouver area, with a population of approximately 2.4 million, is the third-largest urban area in Canada and the largest in Western Canada. Its population is expected to reach 3.5 million by 2041 (World Population Review, 2019).

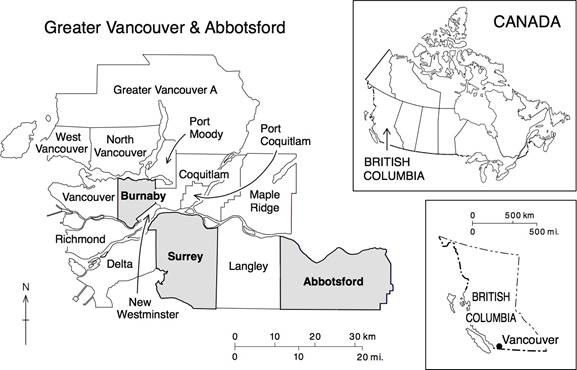

Immigration is a fundamental driver of the region’s population growth. In 2018, 28.3% of British Columbia’s population was born outside Canada, and about 30,000-40,000 international immigrants settle in Metro Vancouver annually (NewToBC, 2018; Statistics Canada, 2016). Of the 23 000 Mexicans of ethnic origin, most have settled in Metro Vancouver (about 5 000). Most Mexican immigrants in British Columbia want to live in Vancouver. However, the high cost of housing in the city has made the surrounding suburban areas important destinations, especially Surrey (about 2 000), Burnaby (about 1 500), and Abbotsford (about 600) (see Figure 1) (NewToBC, 2018; Statistics Canada, 2016). These three suburbs have experienced unprecedented population growth in the last few decades, mainly due to immigration from Asia and the Middle East (see Figure 2) (Statistics Canada, 2016). Immigrants and refugees tend to settle in specific areas in Burnaby (e.g., Metrotown) and Surrey (e.g., City Centre, Whalley, parts of Guildford, and central Newton). These concentrations are associated with areas of low-cost market rental housing and are well-served by public transportation routes (Fiedler et al., 2006; Tood, 2019).

Source: Elaborated by Carolyn King based on data from Statistics Canada (2016).

Figure 1 Greater Vancouver and Abbotsford

Source: Elaborated by Carolyn King based on data from Statistics Canada (2016).

Figure 2 Distribution of Immigrants as a Percentage of Total Population in Burnaby, Surrey, and Abbotsford

Methodology

This qualitative study focused on the Vancouver suburbs of Burnaby, Surrey, and Abbotsford (Figure 1), which have recently become increasingly important destinations for immigrants, including Mexicans. Informal semi-structured interviews were held with 60 key community/service leaders and providers from local organizations supporting Latin American immigrants (e.g., settlement organizations, community centres, churches) in each of the three suburbs. Open-ended questions explored issues such as the housing experiences and challenges faced by recently arrived immigrants in securing affordable housing, settlement programs and housing services provided to new immigrants, and ways to help them integrate and increase the supply of affordable housing.

Interviews lasted about 40-60 minutes and were conducted by telephone (48) or in person (12). They were audio-recorded with consent, transcribed, and analyzed through thematic analysis. Interviewees included social workers, public servants, housing specialists, and immigrant service experts. Participants were identified mainly from government directories, telephone directories, and local websites/community services. Purposive sampling was used to select participants with extensive knowledge about housing markets in Metro Vancouver and the settlement and housing experiences of immigrants in the suburbs.

The following sections present the results. While the findings are specific to the Vancouver area, they may have implications for other regions in Canada and beyond.

Results

Key informants identified several barriers that prevent Mexican immigrants living in the Vancouver suburbs from successfully integrating into Canadian society: access to affordable housing, lack of information about settlement services, language barriers, and access to gainful and sustained employment.

Barriers Encountered in the Suburbs of Vancouver

Housing

All key informants identified the lack of affordable housing as one of the biggest settlement challenges. One noted that the lack of stable housing adds to other problems:

Immigrants come with the idea that Canada is a first-world country, and everything will be easier here, but the first thing you need is a home. If you do not have a home, you do not have food or emotional stability to go out and look for work. Then, immigrants realize that they must live with another family, sometimes seven people in a space of two rooms, and this affects [them negatively] because when there are many people, there are also problems, and they feel annoyed or worried, and this affects even whether or not they find decent jobs (J. Álvarez, personal communication, February 9, 2019).

Unaffordable housing may leave many recent low-income immigrants with no choice but to rent in cheaper homes that have no heating, are overcrowded, may have infestations and are generally unhealthy for survival:

The only option for most recent migrants is to live in basements, including illegal basements, or in houses where sharing a bedroom with several people is normal. People who live in these conditions lose their privacy. In addition, sometimes people live in houses where there is no heating or where there is an infestation of cockroaches and mice (M. Benítez, personal communication, March 10, 2009).

Several interviewees noted how expensive the real estate market is in British Columbia, particularly in the Vancouver Metropolitan area, which provides very few options for future home ownership, especially for poor or low-income immigrants and refugees.

People cannot afford to live in a decent house, not because they are not working but because British Columbia is so expensive (J. Carrillo, personal communication, March 9, 2009).

The lower mainland [Vancouver] is the worst place to be a recent immigrant. If you live here, you must pay to live here. Here you pay for the weather (A. Juventino, personal communication, March 19, 2009).

High rental fees are not the sole problem: discrimination by landlords based on language, national origin, credit/employment history, or religion was identified as barriers encountered by newcomers. One interviewee noted that landlords prefer to rent to people with stable employment and credit history, which compounds struggles as immigrants seek accommodation:

The situation of newcomers is difficult. At least in Surrey, where I work, landlords prefer that whoever rents in their homes are people from India with secure employment, positive credit history, and who sign a contract of at least one year. All these requirements are difficult to have, especially when you are new to the city and still do not know where to go to find work (J. López, personal communication, March 30, 2009).

Another interview participant noted:

Landlords do not like to rent to people who are under government assistance. They are less likely to rent to refugee claimants because they do not have a permanent status in Canada yet and can leave the country anytime (M. Benítez, personal communication, March 12, 2009).

Social media platforms such as Facebook groups can provide support and settlement services to Mexican immigrants who have not yet entered the country. Yet, some fraudulent groups claiming to offer similar services have fleeced innocent victims:

Facebook groups of Mexicans in Vancouver or Latinos in Vancouver offer valuable information for newcomers and even for those who are about to arrive. Work, housing, and the sale of work equipment are offered. It is a great tool. However, I recommend verifying very well who is behind each publication (...) It is very sad to hear that there are people who have been victims of fraud. Sometimes they ask for a deposit in advance, and when people arrive in Canada, they find that they have been scammed because the person who made the deposit has disappeared from Facebook or WhatsApp (M. Benítez, personal communication, March 12, 2009).

As will be explored subsequently, lack of information and language barriers intersect with the settlements and housing needs of immigrants, based on interview findings.

Lack of Information About Settlement Services

Immigrant service organizations (ISOs) can help integrate newcomers living in Canada, but many Mexican immigrants prefer to rely on family, friends, and relatives. Those who arrive with assets, income, or family ties tend to be more successful. As one interviewee noted:

Those that can settle faster are the ones who bring money and/or have family and friends in Canada. They are already 80% ahead of the others. However, newcomers do not reach out to organizations because they do not know they exist. They go to Facebook and/or believe what other people tell them. In addition, they are not always informed about programs that can assist newcomers (M. Smith, personal communication, March 12, 2009).

Immigrants who do not seek the services of ISOs may not be aware of housing laws, and some landlords have taken advantage of such unawareness. For example, asking for large non- refundable deposits, even though this is not permitted:

An important problem facing the Latino community is the unawareness of laws such as the Tenancy Act. They do not know their rights and responsibilities, as well as the rights and responsibilities of the landlords. Sometimes the landlord takes advantage of them, and they do not know and think it is normal behavior because, in Latin America, the housing market is unregulated, and we are not used to rules and protection (M. Benítez, personal communication, March 12, 2009).

Other interviewees also noted that newly arrived immigrants do not reach out to ISOs or similar services and instead seek Facebook group suggestions or advice from friends or family. One commented on the importance of internet resources:

Technology has made it easier for immigrants now. They can easily get a lot of settlement information from people already established in Canada. They can even find jobs before arriving. Although, we need to be aware of fraud. We hear that people have been offered work permits and jobs through social media. [In some cases], people are asked to send money to process their applications, and after sending the money, it turns out to be a fraud. We always tell people that the only way to come legally is through Canada’s [Ministry of] Immigration and Citizenship (M. Buckley, personal communication, March 17, 2009).

Language Barriers

According to interviewees, many immigrants experience language barriers during settlement and integration in Canada. Although some ISOs offer free English classes, these may not be available at convenient times, or immigrants may not be aware of them. For newcomers, low levels of education and a lack of English proficiency are significant liabilities to entering the job market, even for highly qualified and skilled workers. An interviewee commented:

When an immigrant has limited English proficiency, even though they are professionals, they get fewer opportunities to advance in their careers. They have problems validating accreditations. Even doctors who cannot handle English receive little help from the government, even when there is a need for doctors throughout Canada (B. Carranza, personal communication, March 22, 2009).

Several interviewees noted that many newcomers are unaware of services because none exist in their countries of origin or that newcomers may have unfavourable opinions of such organizations based on their experiences back home.

Most newcomers do not know that there are resources to access settlement services. Newcomers often call with a lump in the throat, with the idea that if they open their mouths, the owner [landlord] will take them out, or they will no longer treat them well. We need more education; the tenant must understand that Canada is not like our countries, where the legal processes are different. Here we provide newcomers with letters, templates, and advice to quote the law and support the petition on living in a more decent place (M. Quito, personal communication, March 14, 2009).

Another interviewee commented:

Language barriers and not being able to find meaningful employment are enormous obstacles when trying to settle in a new country. Here in British Columbia, there is no channeling. Channeling resources can improve customer service where not only settlement companies follow their mandates because the results are not so significant and can limit the development of the settlement worker and, in general, of new immigrants. This does not reflect the real need of the immigrant since the worker has to fill his quota. The only thing they are doing is filling out the numbers, and the support to find housing for the new migrant is being neglected (M. Gurugh, personal communication, March 19, 2009).

Overall, communication and unawareness about settlement agencies (NGOs or government- sponsored) can be huge barriers for immigrants and can prevent them from successfully navigating social support systems.

Employment

Key informants also identified several challenges related to employment. They commented that many immigrants are shocked when they find their degrees and credentials are not recognized in Canada. As a result of this and their lack of Canadian work experience, many are forced into the ‘secondary’ labour market, which involves lower wages, poor working conditions, and little opportunity for promotion. Several interviewees also commented on how immigrant status and education level affect settlement and housing experiences and referred to the significant differences between two groups of Mexican immigrants:

We are talking about two types of Mexicans: those whom Canada has historically received and are qualified, and those who are recently arriving from Mexico or the United States-the refugees. Each one faces different difficulties. The first group adapts more quickly, but the second group needs more support and resources from civil organizations (M. Quito, personal communication, March 29, 2009).

Regarding the broader Latino community, another interviewee noted:

The Latino community is a changing community. On the one hand, Canada welcomes highly skilled Latinos with good English skills and less difficulty finding housing and settling easily. On the other hand, more recently arrived Latinos, including Mexicans, coming as refugees with no English skills, represent a challenge to immigrant integration (M. Benítez, personal communication, March 12, 2009).

In Canada, some professionals need a Canadian license or accreditation, depending on specific professions. This can take years, and even doctors, teachers, architects, and engineers can end up working in cleaning or construction jobs. Interviewees referred to the shock and disappointment associated with unmet expectations about employment:

I worked for many years in my country as a journalist, I thought that when I arrived in Canada, I could find a similar job, but when I recently arrived, I worked cleaning houses for a long time. After several years, I realized that I have not come to clean. I needed to achieve more than that. All this after 12 years where I was depressed, sometimes I thought it was better to return to my country, even if they killed me, than working for so long cleaning or in a factory. I had tendonitis problems. My body never got used to heavy physical work (A. Salinas, personal communication, February 12, 2009).

Recommendations for housing new canadians

Three main themes emerged related to reducing the challenges faced by immigrants: (a) access to affordable, suitable, and adequate housing, (b) access to more information, and (c) a more collaborative approach to housing and information-sharing between different levels of government, housing providers, and settlement agencies.

Access to Affordable, Suitable, and Adequate Housing

The lack of affordable housing is a significant issue for immigrants and their Canadian-born counterparts living in the Vancouver area. One key informant noted:

The government is addressing the housing problems of 10 years ago. They are no longer the same. Now they are providing subsidized housing to people who have been on the waiting lists for years. They may no longer need support, and for those who need it now, there is no support (P. García, personal communication, March 4, 2009).

Interviewees also referred to discrimination by property owners making the search for affordable housing even more difficult. Participants identified some of the strategies used, including refusal to rent because some immigrant groups’ norms for larger families may contribute to overcrowding. Also mentioned were immigrants’ customs (e.g., ongoing visits from compatriots and smelly cooking) and requiring newcomers to obtain a guarantor or pre-pay rent:

The owners of the houses (...) ask for a larger [than allowed by law] deposit. They want immigrants to show that they have enough money in the bank for a few months if they run out of work. In addition, the conditions of the houses are not always good. Some houses are cold in the winter, especially in the basements, and this causes health problems for those residing there that ultimately affect their work (A. Salinas, personal communication, February 12, 2009).

Some interviewees commented that this type of discrimination needs to be taken seriously by the local government. One noted that immigrant renters may not complain about discrimination or poor housing living conditions because their housing conditions may still be better than those they left in Mexico. However, silence can come at a cost, and some interviewees also spoke about mental health problems caused by perceived housing discrimination, such as stress and anxiety. Some key informants were critical of some provincial government agencies for their lack of accountability on housing issues. One felt that the functioning of BC Housing, a provincial institution which administers all subsidized housing in the province, is particularly problematic and pointed to the urgent need for better and more transparent accountability to avoid abuse:

The government needs to find a better way to supervise those families under BC Housing because there are families that have been living with subsidized housing for years and no longer need it. I know of at least three families with engineers working full-time and living in subsidized housing (S. Sanders, personal communication, February 12, 2009).

Interviewees felt that better regulation of the rental market is another aspect of government accountability that requires attention, specifically by enforcing housing standards to protect the well-being of tenants. Although they were aware that some measures have been taken (e.g., Housing Vancouver Strategy),1 they referred to the need for all three levels of government to adopt housing policies and strategies to address the housing needs of newcomers and British Columbians in general. They identified the need for more affordable housing (rental and homeownership). Most felt this could be done by incentivizing either the profit or non-profit sectors and referred to the importance of exploring cooperative and non-profit options to increase the supply of social housing.

Access to More Information

Key informants noted that due to the increasing Latino community in the Vancouver area, particularly Mexican immigrants, more orientation programs should be offered in Spanish. One commented:

Most settlement organizations in British Columbia did not offer services in Spanish to permanent residents. OPTIONS and Abbotsford Community Services have offered services in Spanish for many years because they also work with farm workers. Since Trump took office, the wave of refugee claimants has increased, making it necessary for settlement agencies to offer more services in Spanish (A. Smith, personal communication, February 19, 2009).

Others referred to the need to teach new immigrants about important things such as housing laws, housing costs, rights, obligations as tenants, etcetera. As noted above, some referred to newcomers paying huge deposits that may not be refunded because they are unaware of housing laws:

It is important to know your rights and responsibilities. However, our community is a busy one. Most recent immigrants have two jobs or low-paying ones. This gives them no time to educate themselves about the housing laws in British Columbia (A. García, personal communication, February 12, 2009).

One key informant said that landlords also need to be educated about laws so that they can help immigrants secure safe housing:

In my opinion, the government should incentivize those who rent to people who have arrived in the country in the last five years. This would allow more homeowners to offer more opportunities to people who have just arrived and still do not have stable jobs (A. Salinas, personal communication, February 12, 2009).

Some key informants also suggested that all levels of government, including local settlement agencies, should provide newcomers with more realistic information before and after arrival to Canada. Specifically, they felt newcomers should be made more aware of the high living costs in the Vancouver area, housing availability, rights, and obligations as tenants-and that they should receive more information about employment opportunities and the job market.

A More Collaborative Approach to Housing

All key informants suggested that various levels of government should share information and work together to address the housing needs of all British Columbians. One said:

Local governments must unite and act. Young people finish college, and there are no jobs, or [there’s] jobs that are poorly paid and a super-expensive life. This is forcing young people to leave Vancouver. Many of those [for example, affluent foreigners] who can afford houses here do not even live or work in Vancouver, so they evade taxes. If the government does not act, we will be left without young people in British Columbia (A. Smith, personal communication, February 19, 2009).

Some interviewees felt that settlement organizations, which are usually the first point of contact for newcomers, should do more about housing services by providing reliable information about affordable or subsidized housing (e.g., waiting times for subsidized housing, vacancy rates, and landlord and tenant rights). One said:

Nobody knows how BC Housing operates. When my clients come and we submit their application for BC Housing, they expect me to know how long it will take, and my answer always is: ‘We need to wait.’ It would be nice to have more information2 about BC Housing and its selection processes (M. Gonzalo, personal communication, February 28, 2009).

Overall, interviews revealed that more coordination is needed between housing support programs and immigrant service agencies. Also, accurate and realistic information about housing should be delivered before and after newcomers arrive; housing-support kiosks connecting newcomers with services at entry points could serve this purpose.

Conclusion

Canada attracts immigrants from around the world, but immigration from Mexico is a relatively recent phenomenon. Unlike the United States, where Mexican communities have been established and flourished over time, in Canada (including Vancouver and its suburbs), Mexicans do not have the benefit of well-established and institutionally complete ethnic enclaves to assist them in the settling and integration process.

Immigrants face barriers that can lead to poverty, homelessness, and exploitation. The interviews with key informants helped clarify some of the barriers faced by Mexican immigrants living in the suburbs of Vancouver (Abbotsford, Burnaby, and Surrey). Significant barriers we identified include lack of access to affordable housing in the rental and homeownership market and lack of information about settlement services and employment, including the non-recognition of employment experiences and foreign credentials. These barriers are congruent with the findings of previous Canadian studies (Carter & Vitiello, 2012; Drolet & Robertson, 2011; Fong & Berry, 2017; Pendakur & Pendakur, 2015; Teixeira, Li, & Kobayashi, 2012).

Access to affordable, adequate, and suitable housing is a key factor in the successful integration of immigrants. Housing throughout many regions of Canada, especially Vancouver and its suburbs, has become less affordable. This is a major problem for new immigrants, including some Mexicans, who tend to be under enormous financial stress. The limited supply of social housing in Burnaby, Surrey, and Abbotsford reflects this reality, and long wait lists make it difficult for low-income immigrants to access affordable, adequate, and suitable rental housing, let alone future homeownership.

Expensive, poor-quality housing can lead to social exclusion, segregation, and slower integration of recent immigrants into mainstream society. All key informants felt that the federal and provincial governments should provide more subsidized housing for low-income immigrants and develop better policies for renters and homeowners, including vulnerable low-income groups like immigrants and refugees. Other Canadian studies have also identified housing affordability as a major national issue and the need for better housing policies to accommodate the needs and preferences of Canada’s increasingly culturally diverse population (Carter & Vitiello, 2012; Fong & Berry, 2017; Hiebert, Mendez, & Wyly, 2008; Murdie & Skop, 2012; Teixeira, 2014).

The housing challenges faced by immigrants and outlined by our key informants are consistent with those of other vulnerable low-income groups (e.g., refugees, older seniors, single parents, and students) in large Canadian cities and suburbs with high housing costs. Competitive housing markets act as a hurdle to such groups in various ways (Carter & Vitiello, 2012; Hulchanski, 2010; Ley & Lynch, 2020; Teixeira, 2017). Federal policies on housing have been minimal in the past 25 years. It is not surprising then to know that Canada possesses the smallest housing sector in any Western nation outside the United States.

The absence of regular and fair regulation has led to rents increasing double the annual inflation rate and not many constructions of rental units in cities including Vancouver and Toronto. Only recently, the housing market in British Columbia is witnessing key legislative changes brought by the New Democratic Party (NDP), such as the Foreign Ownership Registry, Housing Vancouver, and other associated measures to improve housing affordability (Gordon, 2020; Younglai & Wang, 2019). Prime Minister Trudeau’s government started a national consultation process to develop better housing policies and action plans for renters and homeowners, including vulnerable low- income groups like immigrants and refugees. However, its progress so far is not significant (Rose, 2019).

Interviews revealed that Mexican immigrants in the Vancouver area rely extensively on their informal social networks (family members, friends, and social media) to assist with their initial settlement needs, including finding housing and jobs. They may even share accommodation with relatives or friends. Many hope to become homeowners but may be unaware of the numerous barriers they may encounter to achieve this significant goal.

Key informants also referred to discriminatory practices by landlords. The economic reality in Vancouver’s suburbs means landlords can decide who gets rental housing and at what price. Overall, discriminatory practices by landlords as well as other urban gatekeepers (e.g., housing agencies and real estate agents) need to be taken more seriously by local governments.

Another significant challenge for Mexican immigrants is employment. Interviewees noted that it is difficult for recently arrived immigrants to find appropriate employment that matches their education, work experience, and skills. Lack of work experience in Canada and the credential recognition process prevents even some skilled immigrants from finding appropriate employment. Governments, policymakers, and settlement service providers should develop and implement better social development policies to facilitate access to language training and accreditation processes that can give validity to education and work experience credentials. Previous Canadian studies have also identified job market barriers during the settlement and integration of immigrants in Canadian cities (Kaushik & Drolet, 2018; Qadeer, 2016; Pendakur & Pendakur, 2015).

Regarding settlement services, interviews revealed that different levels of government have diverse information and services available to support recently arrived immigrants. New immigrants need information about housing and other supports such as language and job training. Also, key informants stressed the need for more collaboration and coordination-not only between different levels of government but also with ISOs to provide comprehensive services at one location. Appropriate services and policies should also be based on input from immigrant groups (Drolet & Robertson, 2011; Simich et al., 2005; Teixeira, 2014).

The suburbs of Vancouver are gradually becoming important immigrant-receiving societies. They are becoming increasingly diverse and multicultural, and their varied immigrant populations are shaping the social, cultural, economic, and political landscape. Few comparative studies (Hulchanski, 2010; Teixeira, 2014) have explored Canada’s suburban multicultural context, even though it can serve as an excellent laboratory for the study of multiculturalism and how ethnic and racial diversity affects urban structures and processes. Including the functioning of local housing markets-a key factor in the successful integration of immigrants.

Previous studies (Murdie & Skop, 2012) have documented the recent trend of immigrants bypassing the inner city and settling directly in well-established or new suburbs. However, many of the intricacies of the settlement and the suburban housing experiences of new immigrants remain unclear. More comparative research is needed to explore the housing experiences of visible and non-visible minorities, including Canadian-born minorities, and identify why certain groups are more successful than others in finding affordable housing in the city/neighbourhood of their choice.

Also, more longitudinal research is needed to clarify immigrants’ housing trajectories over time. For example, how they adjust to the new realities of complex/expensive housing markets; how successful they are in attaining affordable, adequate, and suitable housing; and how they become more settled and integrated into new suburban societies. This kind of longitudinal research could be guided by questions such as do immigrants face fewer barriers/challenges in accessing affordable, adequate, and suitable housing over time as they become more settled into life in the suburbs? Do their cultural practices and coping strategies adjust to the new realities of increasingly complex and expensive housing markets in the suburbs? How successful are these culturally oriented strategies? How welcoming are ‘new’ suburbs, and are they prepared to accommodate the cultural needs and preferences of an increasingly diverse and economically disadvantaged population? How can immigrants achieve the goal of homeownership, and how does homeownership benefit immigrant families? Overall, the findings will help clarify the numerous barriers/challenges immigrants may encounter to achieve this important goal in one of North America’s most expensive housing markets.

Finally, further research is needed to explore the discriminatory practices of landlords. Discrimination and prejudice within Canada’s suburban markets remain largely understudied. The findings will help inform antiracist policies and practices.

text in

text in