Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death globally and is an increasing contributor to disability and rising health care costs1,2. Hypertension and dyslipidemia are key risk factors of CVD. The risk of CVD complications associated with co-existing hypertension and dyslipidemia are generally greater than the sum of the individual risk factors3. Worldwide, hypertension is estimated to cause 10.4 million deaths/year4, while dyslipidemia, especially high cholesterol levels, causes an average of 2.6 million deaths and 29.7 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYS)5. In Latin America (LATAM), CVDs contribute almost a million deaths annually6. Out of the estimated 1.13 billion people worldwide living with hypertension, most (two-thirds) live in low- and middle-income countries including the ones in LATAM7.

Dyslipidemia based on triglyceride levels in LATAM has been reported to range from 25.5% to 31.2%8, while hypertension ranges from 9% to 29% in select cities of South America9. The World Health Organization targets to reduce the prevalence of hypertension by 25% by 2025 (baseline 2010)7.

Hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes have common pathophysiology related with overweight and obesity; hence, when co-existing in a person, they have a synergistic and negative effect on the cardiovascular health10. Hypertension and dyslipidemia co-exist in almost 15-31% of cases causing more than an additive adverse impact resulting into enhanced risk for atherosclerosis and CVDs11. To reduce the combined burden of the two conditions, it is vital to comprehend local health system challenges and the prevalent country-specific issues which contribute to the current state of poor control of these two conditions. Appropriate strategies for detection, diagnosis, treatment, and control are needed based on country-specific data to tackle these diseases together, which can compound into a major economic and social problem in a middle-income country like Mexico10.

Despite the government’s attempts to provide healthcare access to everyone, CVDs are the leading cause of death in Mexico12. In spite of more than two decades of healthcare reform projects in Mexico, the universal coverage of care for non-communicable diseases such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes suffers from large disparities and inequality in access13,14. The percentage of people who have received plasma lipid measurement at least once and those who have received measurement of fasting lipids remains low. Many of the dyslipidemias are never enrolled in treatment programs14. The Mexican government has addressed non-communicable diseases through prevention plans, regulations, and policies (PRPs) that seek to address social and environmental factors. PRPs face a variety of challenges in terms of efficacy, the majority of which are linked to resources, implementation, and adherence. PRPs have also failed to adequately address the integration of individual, medical, social, pharmaceutical, and environmental approaches such as access to physical activity and healthy diet15. Unlike the multiple government and private systems in other countries, the government health system in Mexico is fragmented into multiple, parallel, and redundant health systems for different population groups (such as Health Maintenance Organizations, indemnity health plans, and the like) which ends up creating incentives that maintain or increase inequity rather than channeling public resources to the most pressing needs16.

There is a scarcity of country-specific data with respect to hypertension and dyslipidemia in LATAM countries including Mexico, owing to lack of updated situational analysis to understand the current scenario and related issues9. To overcome this shortcoming and to reflect current status of healthcare provision, the authors adopted a patient journey approach based on the Mapping the Patient Journey Towards Actionable Beyond the Pill Solutions for Non-communicable Diseases (MAPS) methodology17. The current semi-systematic review aimed to synthesize country-specific data for hypertension and dyslipidemia in various stages of the patient disease journey including, awareness, screening, diagnosis, treatment, adherence, and control of these conditions in Mexico. The study also aimed to identify data gaps across patient journey touchpoints that can help mitigate cardiovascular risk and subsequent mortality in patients. This would give a ground for making recommendations for a better management of patients with hypertension and dyslipidemia.

Materials and methods

The current study was a semi-systematic review conducted for published articles describing patient journey stages for hypertension and dyslipidemia. The definitions used in the review are described in table 1. Six steps were used to construct the evidence map: (1) developing a comprehensive search strategy; (2) establishing the inclusion and exclusion criteria; (3) screening and shortlisting; (4) supplementing with additional and/or local data; (5) data extraction and synthesis; and (6) evidence mapping.

Table 1 Definitions of the terms used in the study

| Criteria | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Hypertension | Hypertension was defined as % of respondents having average systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 ≥mmHg and/or average diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90 ≥mmHg |

| Hypercholesterolemia | Hypercholesterolemia was defined as total cholesterol (TC) of ≥ 5.0 mmol/L OR ≥ 200.0 mg/dL |

| Awareness | Self-reported or any prior diagnosis of high total serum cholesterol or hypertension by a healthcare professional |

| Screening | Proportion of respondents who had their cholesterol levels or blood pressure (BP) measured by a doctor or any other health worker |

| Diagnosis | Patients diagnosed with hypercholesterolemia disorder or hypertension by a healthcare professional |

| Treatment | Use of medications for management of the respondent’s high cholesterol or high BP |

| Adherence | Proportion of respondents indicating adherence and/or compliance to the prescribed cholesterol lowering medications or BP medications |

| Control | Proportion of patients achieving a target cholesterol of ≤ 5.0 mmol/L OR ≤ 200 mg/dL with treatment or a target BP of ≤ 140/90 mmHg with treatment |

Search strategy

A structured search was conducted on EMBASE and MEDLINE using OVID access for articles concerning the Mexico region published in English from 2010 till 2019, whose full text was available, except for conference abstracts. All types of articles were included except thesis abstracts, letters to the editor, and editorials.

Keywords used for the search included:

– Hypertension OR blood pressure (BP) OR hypertensives AND epidemiology OR prevalence OR incidence OR national OR survey OR registry AND awareness OR knowledge OR health literacy OR screening diagnosis OR diagnosed OR undiagnosed OR treatment OR treated OR untreated OR control OR controlled OR uncontrolled OR adherence OR compliance OR adhere OR therapy OR non-adherence AND Mexico.

– Dyslipidemia OR hypercholesterolemia OR cholesterol OR triglycerides OR LDL AND epidemiology OR prevalence OR incidence OR national OR survey OR registry OR Statistics AND health literacy OR screening OR awareness OR knowledge OR treated OR treatment OR diagnosis OR undiagnosed OR diagnosed OR therapy OR controlled OR control OR uncontrolled OR adherence OR adhere OR compliance AND Mexico OR Brazil OR Argentina OR Latin America.

To address data gaps in the structure search, an unstructured literature search was conducted without any restrictions, on the websites of Incidence and Prevalence Database (IPD), World Health Organization (WHO), Mexican Ministry of Health, and Google. Last search was run on 28 August 2020 for hypertension and 12 November 2019 for dyslipidemia.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria and screening of articles:

Articles identified from the semi-systematic database search were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria were: (1) systematic review and/or meta-analysis, randomized controlled study, observational study, narrative reviews (both full-text articles published and conference abstracts), (2) concerning adult populations with the age of ≥ 18 years old, (3) reporting quantitative data from patients’ journey touchpoints for hypertension and dyslipidemia, including awareness, screening, diagnosis, treatment, adherence and control, and (4) conducted on patient populations focusing exclusively on hypertension and dyslipidemia.

Articles related to specific patient subgroups, without nationally representative populations, thesis abstract, letters to the editor, editorials, or case studies were initially excluded from the review. In case patient journey data was not available from included articles, articles representative of the entire region and belonging to patient subgroups were included in the review. Furthermore, any identified data gaps were supplemented with publications in local languages and anecdotal data from authors who were also the local clinical experts.

An independent reviewer conducted the semi-systematic literature search to extract data from both structured and unstructured search. The titles and abstracts of the retrieved publications were screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A second independent reviewer assessed these search results based on study title, article citation, author names, year of publication, abstract, study design, study participants, and study setting of the retrieved search publications and excluded the non-relevant publications. Any disagreements were reconciled by discussions among the reviewers and co-authors.

Data extraction and analysis

Relevant data from the included articles were exported to Microsoft Excel by the reviewers and was verified by the co-authors to maintain consistency. The synthesized evidence was represented as an evidence gap map followed by synthesis. Anecdotal data was considered for adherence for the prescription of hypertension.

Data from the included articles with respect to the patient journey touchpoint such as prevalence, awareness, screening, diagnosis, treatment, adherence, and control of hypertension and dyslipidemia were pooled and synthesized by weighted or simple means to minimize bias arising from the methodological limitations of different studies. A summary of outcomes is visually presented in the form of a tabular summary of outcome results.

Results

Overview of the included studies

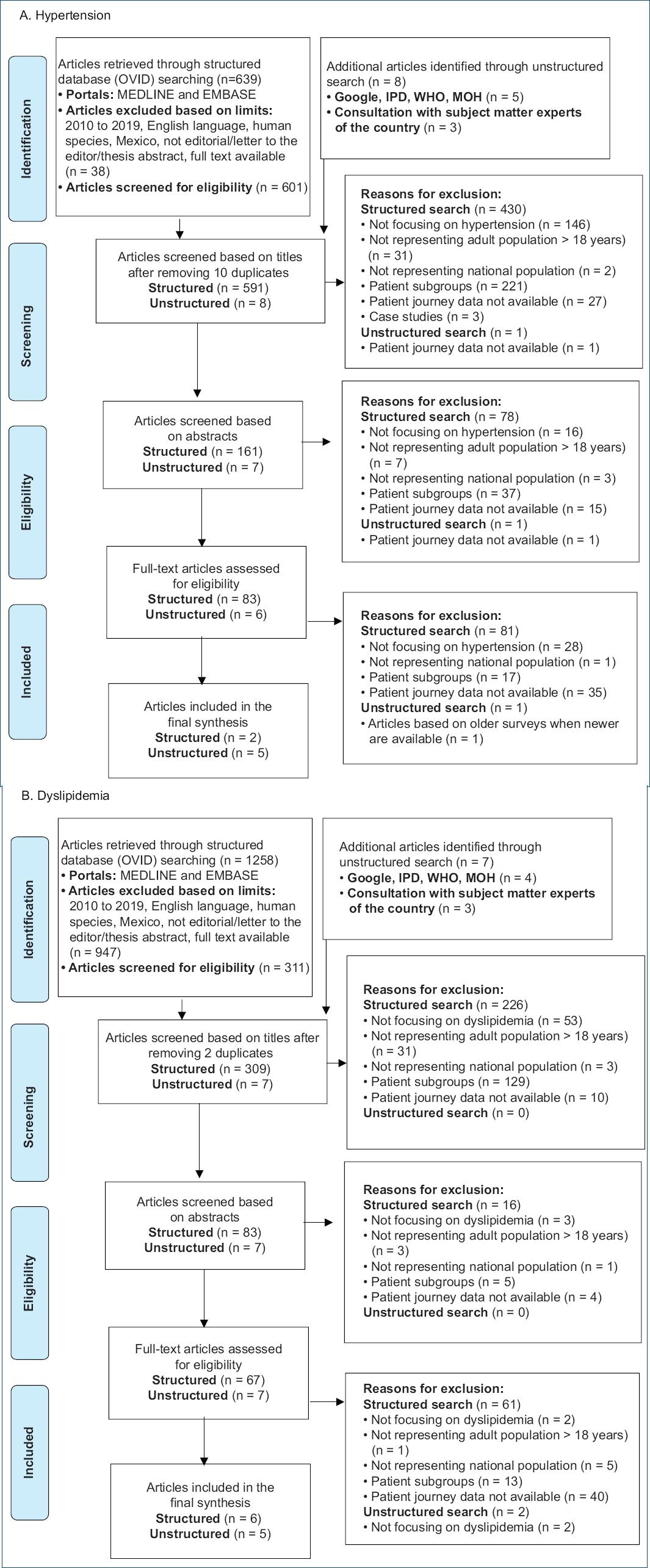

For hypertension, 639 articles from structured search and eight articles from unstructured search were retrieved, including three articles suggested by authors of this review who are key opinion leaders or experts of the subject in the country. Two articles from structured and five articles from unstructured searches were included in the final data synthesis including two articles suggested by authors. These articles included three reports, one secondary data analysis, one position paper, one cross-sectional study, and one comparative analysis of national surveys.

For dyslipidemia, 1258 articles from structured search and seven articles from unstructured search, including three articles suggested by authors, were retrieved. Six articles from structured and five records from unstructured searches were included in the final data synthesis; including three articles suggested by authors. These articles included four reports, four secondary data analyses of surveys, one secondary data analysis of registry data, one cross-sectional study, and one visualization tool.

The flow of the articles through the review is depicted in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart is presented in figure 1 and table 2.

Figure 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram showing flow of articles. IPD: incidence and prevalence database; WHO: World Health Organization; MOH: Ministry of Health.

Table 2 Description of the included studies

| S.No. | Author/title | Year | Sample size | Patient journey touchpoints |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | ||||

| 1 | Nayu Ikeda et al.20 | 2014 | 11,406/21,230 | Prevalence (14.8%/29.5%) Diagnosis (49.4%/55.8%) Treatment (40.9%/49.5%) Control (27.1%/28%) |

| 2 | Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 201432 | 2014 | 12,03,55,000 | Prevalence (20%) |

| 3 | ENSANUT 201610,20 | 2016 | 8,352 | Prevalence (25.5%) Awareness (60%) Diagnosis (59.6%) Treatment (79.3%) Control (45.6%) |

| 4 | ENSANUT 201810,20 | 2018 | 8,27,00,000 | Diagnosis (18.4%) |

| 5 | Lloyd-Sherlock et al.22 | 2014 | 2,281 | Prevalence (58.2%) Awareness (44.6%) Control (11.8%) |

| 6 | Hernandez-Hernandez et al.23 | 2010 | 1,722 | Prevalence (11.7%) Screening (97.5%) Diagnosis (24.3%) Treatment (65.7%) Control (41%) |

| 7 | Alcocer et al.10 | 2019 | 8,50,00,000 | Prevalence (30%) Awareness (60%) Treatment (50%) Control (50%) |

| 8 | Anecdotal data (na) | Adherence (50%) | ||

| Dyslipidemia | ||||

| 1 | WHO GHO Visualizations Tool5 | 2008 | 11,08,15,000 | Prevalence (49.5%) |

| 2 | Aguilar-Salinas et al.2,24 | 2010 | 4,040 | Prevalence (43.6%) Awareness (8.6%) |

| 3 | Gaxiola et al.26 | 2010 | 837 | Prevalence (57.8%) |

| 4 | Incidence and Prevalence database5 | 2019 | 1,179/96,031 | Prevalence (48.7%/30.6%) |

| 5 | Gomez-Perez et al.2,24 | 2010 | 4,040 | Awareness (8.6%) Control (30%) |

| 6 | ENSANUT 201810,20 | 2018 | 8,27,00,000 | Prevalence (19.5%) |

| 7 | Vinueza et al.27 | 2010 | 1,722 | Prevalence (16.4%) Treatment (22%) |

| 8 | Gakidou et al.4 | 2011 | 45,446 | Prevalence (35%) |

| 9 | Rivera-Hernandez et al.12 | 2015 | 11,405 | Screening (34.92%) |

| 10 | ENSANUT 201610,20 | 2016 | 8,412 | Screening (44.5%) Diagnosis (28%) |

| 11 | ENSANUT 201210,20 | 2012 | 96,031 | Screening (49.9%) Treatment (69.8%) |

ENSANUT: National Health and Nutrition Survey; WHO: World Health Organization; GHO: Global Health Observatory.

Mapping the evidence

The total population of Mexico was estimated to be 127,576,000. Health literacy in Mexico, as assessed in a subset of adults aged ≥ 20 years old, was reported to be 18%. Pooled estimates for hypertension and dyslipidemia prevalence were 24.1% and 36.7%, respectively. The synthesized evidence (Table 3) indicated that 97.5% underwent screening, 59.9% of patients had awareness of hypertension, 18.4% had hypertension diagnosis, 50% received treatment, 50% were adherent to treatment, and 49.9% had disease control. Similarly, the prevalence of dyslipidemia was estimated as 36.7%, while 48.1% underwent screening, 8.6% of patients had awareness, 28% had dyslipidemia diagnosis, 68.9% received treatment, 50% were adherent to treatment, and 30% had disease control (30%). No data was available for adherence in the published literature. As per the co-authors opinion and anecdotal evidence, adherence was estimated to be 50% for both conditions.

Table 3 Pooled data of included articles for patient journey stages for hypertension and dyslipidemia

| Condition | Prevalence | Awareness | Screening | Diagnosis | Treatment | Adherence | Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 24.1%*a | 59.9%*a | 97.5%a | 18.4%*a | 50.0%*a | 50%b | 49.9%*a |

| Dyslipidemia | 36.7%*a | 8.6%a | 48%*a | 28%a | 69%*a | No data | 30%a |

*Weighted Average;

aPublished Data;

bExpert Opinion Only.

This table shows a high Hypertension and Dyslipidemia prevalence. However, the awareness and screening are higher for Hypertension opening an opportunity window to increase screening and in consequence awareness for Dyslipidemia. This table also shows insufficient data about adherence, Hypertension adherence data is extrapolated of expert opinion and Dyslipidemia adherence is unknown; both are relevant opportunity areas for research.

Discussion

Lack of actionable data is a cause of concern for deriving meaningful conclusions. For hypertension as well as dyslipidemia, screening, awareness, diagnosis, and treatment were quantified as low. Despite the high screening rate for hypertension, the diagnosis was not always established. This may be due to underreporting of hypertension in Mexico due to lack of standardized definitions and cut-offs for both the conditions. According to the Mexican Norm of Hypertension (“Proyecto para la Norma Oficial Mexicana” NOM-030-SSA2-2016), ≥ 140/≥ 90 mmHg is defined as hypertension. Recently the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines defined hypertension if BP is ≥ 130/≥ 80 mmHg, while the 2018 European Society of Cardiology and European Society of Hypertension guidelines preserve the ≥140/≥90 mmHg criteria for the hypertension diagnosis10,18,19. The multitude of definitions of high BP which healthcare practitioners use for hypertension in Mexico leads to inconsistencies in diagnosis10. For example, in the 2012 National Health and Nutrition Survey (ENSANUT or “Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición” 2012), the criteria for hypertension was ≥ 135/≥ 85 mmHg (criteria used for metabolic syndrome) whereas it was ≥ 140/≥ 90 mmHg in the 2018 National Health and Nutrition Survey (ENSANUT 2018)10,20. Further, the heterogeneity in the measuring devices like oscilometric and mercury sphygmomanometer leads alto to significant variations in diagnosis and prevalence.

Moreover, diagnostic criteria for hypercholesterolemia, which was taken as a proxy for dyslipidemia, have varied heavily from 200 mg/dL to 220 or 240 mg/dL and need standard and updated criteria for diagnosis. There is a strong need for a standardized protocol to measure BP and total cholesterol and fractions levels even in surveys20. Heterogeneity and low knowledge and compliance to the practicing guidelines by practitioners is another matter of concern; “Official Mexican Norms” (Normas Oficiales Mexicanas) for hypertension and dyslipidemia have not been revised for a long time and are currently under review21.

The review noted that the prevalence of hypertension increased sharply with age, was associated with the poorer sections of the society, and in women22,23. Southern Mexico has high prevalence of hypertensive adults who are untreated whereas northern Mexico has high prevalence of dyslipidemia. Hence, region-specific strategies are needed to counter CVD risk24. Recently an increasing rural awareness was also reported, which may be a consequence of an effective intervention like Mexico’s Popular Health Insurance Program22.

Cardiovascular risk due to combined effect of hypertension and dyslipidemia

The synergistic action of more than one risk factor in an individual, such as including hypertension and dyslipidemia, leads to atherosclerotic disease (detected via ultrasonography of carotids and femoral arteries) correlating it to cardiac or cerebrovascular damage23, such as myocardial infarction, stroke, and other CVDs, and causes subsequent high mortality in Mexico10. Cardiovascular risk stratification indicates that most of the hypertensive population have concomitant risk factors23. The risk scales utilized in Mexico are SCORE, Framingham Risk Score, and more recently introduced Pooled Cohort Equation. Other algorithms as Globorisk and Interheart methods are not used uniformly and usually utilized for patient subgroups only25. This necessitates the uniform use of cardiovascular risk scales which may enable stratification of the patients based on combined risk from multiple variables.

Although articles report that patients receive cardiovascular risk management, the 1-year cardiovascular event rate remains high, indicating a need for adherence and persistence to evidence-based treatment of cardiovascular risk factors and disease26. In spite of vast evidence on the effectiveness of cholesterol reduction in cardiovascular risk reduction, reports show low rates of prescription of lipid-lowering therapy27, that poses a major challenge. Despite CVDs being the leading cause of mortality in Mexico, it is estimated that only 4% of total health expenditure was spent on CVDs in 201524. Around 7.9 million people need long-life treatment with statins in Mexico, which might prove to be a major economic load28.

Estimates suggest that 11.9 million adults need a physician and a dietitian for pharmacologic and nutrition therapy, respectively, while the current number of patients availing diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia is inadequate28. Unclear position about non-pharmacological interventions in this regard remains another challenge29.

Mexican public health institutions aid in providing diagnostic tests and treatment for hypertension and dyslipidemia. Most of the population has access to public health insurance (formerly Seguro Popular, currently Instituto de Salud para el Bienestar or INSABI or Institute of Health for the Well-Being). Even then, reports show a significant usage of preventive and screening services with respect to cholesterol and hypertension in this insurance12. However, low level of adherence among the Mexicans coupled with unhealthy nutrition, sedentary lifestyle and obesity negates the impetus achieved24.

Poor quality and access to care in the public health institutions results due to difficulty in fixing appointments, distance to clinics, as well as dearth of medical personnel and facilities12. This leads the population to private care and out-of-pocket spending for hypertension and dyslipidemia treatment30. Around 25% of patients acquire the treatment in pharmacy and medical offices, and another 25% reach out to private practitioners or specialists. Overall, 80% of the Mexicans are treated by general practitioners and 20% by specialists10,30.

Suggested interventions for reducing cardiovascular risk

The high prevalence of co-morbid factors like hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes in Mexicans highlights the need for aggressive cardiovascular risk reduction through pharmacologic therapy and lifestyle modifications26. There is a huge benefit of providing integrated, evidence-guided, long-term, and oversighted care of multiple cardiovascular risk factors. The need to detect, treat and control optimally all of the risk factors at the same time through innovative solutions is recommended31. Strategies aimed at early intervention with an inclusive assessment of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and other comorbidities are crucial in curtailing CVD effectively10,27. Good quality and combination therapies in line with updated guidelines to treat hypertension and dyslipidemia will improve the acceptance, adherence, persistence, and in consequence control of these risk factors10.

The benefits of early diagnosis and free services offered by the government through public health insurance need highlighting12. Importantly, the Mexican healthcare system should incorporate methods to ensure adherence and persistence to the therapy28. Government media advertisements are needed to reach people with low adherence and persistence levels. Brief and campaign-based government initiatives may not be as effective as new initiatives with an extensive, sustained, and oversighted population reach vision. These will also help to alleviate the social aspect of medical issues like CVDs. Mexican Institute of the Social Security (IMSS) has implemented a preventive model for non-communicable chronic diseases. It has educational programs for adult risk factors and is implementing an educational model in children for lifestyle modification31. Effective lifestyle modifications such as healthy diet and physical activity help to alleviate the ripple effect of high BP and dyslipidemia on the overall body mass index22. Mexicans must be educated and empowered on their responsibility about their health status and the importance of non-pharmacological measures to counter cardiovascular risk, such as wholesome nutrition and adequate physical activity10.

Accuracy in data can be achieved by considering nationally representative surveys in which BP and lipid levels were measured and not self-reported32. There is a strong need to have standardized modules to measure BP and blood lipids. These should include guidelines for training personnel on technique and equipment10. Devices used to measure BP and lipids should be checked for standard certifications to aid in effective diagnosis and management10.

Medical education should extensively teach treatment of hypertension and dyslipidemia. As patients’ first contacts, primary care physicians and specialists should provide preventive therapy also28. There is a need for training physicians for early categorization and stratification of cardiovascular risk based on established scales like atherosclerotic CVD risk score. Ideally, Mexican Government should initiate population-based research in order to have a national scale for risk stratification of risk (cerebral, cardiac, and renal). Continuing medical education programs for the first contact physicians and private practitioners on the end-to-end management of hypertension and dyslipidemia need to provide more comprehensive information and need to be conducted more frequently10.

Study limitations

Limited data were available for patient journey touchpoints despite a comprehensive search. The review was unable to find data on adherence of both hypertension and dyslipidemia. This study tries to talk about patient journey in the two indications, and basis the gap, it is recommended that both are addressed individually. However, we also need to be cognizant of the fact that many patients with hypertension may have underlying dyslipidemia too.

Conclusions

Quantification of patient journey stages revealed sub-optimal status of care for hypertension and dyslipidemia in Mexico. An early, integrated, evidence-based, long-term, and oversighted approach to counter cardiovascular risk is urgently required for dealing with the synergistic effect of cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and dyslipidemia. Solutions should be drawn, keeping in mind the net-benefit concept, economic and social background of a middle-income country like Mexico.

Authors contributions

Enrique Morales contributed in conceptualization, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing the original draft, reviewing and editing manuscript, visualization, and supervision. Carlos Yarleque contributed in conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing the original draft, reviewing and editing the manuscript, visualization, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. Maria L. Almeida contributed in conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing the original draft, reviewing and editing the manuscript, visualization, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)