Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

Share

Agrociencia

On-line version ISSN 2521-9766Print version ISSN 1405-3195

Agrociencia vol.50 n.4 Texcoco May./Jun. 2016

Animal science

Puberty age in pelibuey ewes lambs, daughters of ewes with seasonal or continuous reproductive activity, born out of season

1 Departamentos de Reproducción; Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. 04510. Avenida Universidad 3000. Colonia Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, C. U.

2 Genética y Estadística, Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. 04510. Avenida Universidad 3000. Colonia Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, C. U.

Some Pelibuey sheep do not present a reproductive seasonality that is common in the species. The objective of this study was to determine whether the Pelibuey ewe lambs, daughters of ewes with continuous (C) reproductive activity, begin puberty before the daughters of seasonal ewes (S), when the births occurred outside of season (autumn or winter). The ewe lambs daughters of continuous ewes do not rely on the photoperiod and begin their puberty during the anestrus. To test this, 16 Pelibuey ewe lambs (8C and 8S) born in autumn (November) and 21 ewe lambs (11C and 10S) born in the winter (December-January) were studied. All of them were kept with their mothers and weaned at 90 d of age; they remained in an intensive system and were isolated from contact with males. Starting at four months of age, the weight and body condition were recorded weekly, and blood samples were taken to determine the plasma concentrations of progesterone and to identify the beginning of the ovary activity. Through a variance analysis, the differences in the presentation of puberty between daughters of continuous and seasonal ewes were studied, in each birthing season, through age, weight, body condition at first ovulation, and differential of weight at weaning-weight at first ovulation. The age and weight at puberty was 239.25± 10.96 d and 29.78± 4.39 kg in the ewe lambs born in autumn, and 230.28± 42.71 d and 25± 4.42 kg in ewe lambs born in winter. None of the variables of the daughters of continuous ewes were different from those of seasonal daughters in any of the lambing seasons (p> 0.05). The age at puberty in Pelibuey lambs is independent of the reproductive pattern, seasonal or continuous, of their mothers. Some ewe lambs only need to be exposed to long days for puberty to take place.

Key words: Puberty; lambs; Pelibuey; photoperiod; continuous reproductive activity; Ovis aries

Algunas ovejas Pelibuey no presentan la estacionalidad reproductiva común en la especie. El objetivo de este estudio fue determinar si las corderas Pelibuey, hijas de ovejas con actividad reproductiva continua (C), inician la pubertad antes que las hijas de ovejas estacionales (E), cuando los partos ocurrieron fuera de temporada (otoño o invierno). Las corderas hijas de hembras continuas no se basan en el fotoperiodo e inician su pubertad durante el anestro. Para probar esto, 16 corderas Pelibuey (8C y 8E) nacidas en otoño (noviembre) y 21 corderas (11C y 10E) nacidas en invierno (diciembre-enero) fueron estudiadas. Todas fueron mantenidas con sus madres y destetadas a los 90 d de edad, permanecieron en un sistema intensivo y fueron aisladas del contacto de machos. Desde los cuatro meses de edad, cada semana se registró el peso y la condición corporal y se tomaron muestras sanguíneas para determinar las concentraciones plasmáticas de progesterona e identificar el inicio de la actividad ovárica. Mediante análisis de varianza se estudiaron las diferencias en la presentación de la pubertad entre hijas de hembras continuas y estacionales, en cada época de parición, mediante edad, peso, condición corporal a la primera ovulación y el diferencial del peso al destete-peso a la primera ovulación. La edad y el peso a la pubertad fue 239.25±10.96 d y 29.78±4.39 kg en las corderas nacidas en otoño y 230.28±42.71 d y 25±4.42 kg en las corderas nacidas en invierno. Ninguna variable de las hijas de ovejas continuas fue diferente al de las hijas de estacionales en ninguna de las temporadas de parición (p>0.05). La edad a la pubertad en corderas Pelibuey es independiente del patrón reproductivo estacional o continuo de sus madres. Algunas corderas sólo necesitan exponerse a días largos para que la pubertad ocurra.

Palabras clave: Pubertad; corderas; Pelibuey; fotoperiodo; actividad reproductiva continua; Ovis atries

Introduction

In order to obtain the higher number of births in a ewe, it is convenient for it to begin its reproductive life at an early age (Valencia and Gonzalez-Padilla, 1983). Puberty is defined as the moment when the female has its first heat, but in ewes the first ovulation is considered, since it precedes two or three weeks to the first heat (Foster and Jackson, 2006).

In breeds of temperate origin, puberty is presented between 6 and 18 months of age, when ewes have 50 to 70 % of their adult weights and are in the reproductive season (Hafez, 1952; Dýrmundson, 1981). The breeds of tropical origin like Pelibuey reach puberty at between 6 and 8 months of age, when they are managed in intensive conditions (Cambellas, 1993). In Pelibuey, the lambs born in spring and which are supplemented, can begin to cycle at six months of age, with weights of around 21 kg. But the ewe lambs born in the same production unit during autumn begin to cycle at nine months of age or more, even when their diet has been adequate and they have reached 21 kg since months back. This is because ewes born in autumn and which are supplemented reach the age (6 months) and weight (21 kg) compatible with puberty during February to April. The decrease in reproductive activity was described for these months (Valencia and Gonzalez-Padilla, 1983), so that the ewes have to wait for the adequate season of the year to begin cycling.

In comparison to sheep breeds such as Suffolk, originally from Nordic countries, in which the reproductive seasonality is maintained in medium latitudes (19 °N) (De Lucas et al., 1997), in Pelibuey there are females that are capable of cycling throughout the year, so they are considered continuous (Valencia et al., 2006; Arroyo et al., 2007). These sheep were identified (Valencia et al., 2010; Roldán et al., 2014) through the protocol described by Hanocq et al. (1999): a ewe is considered continuous when it presents ovulation in April for three consecutive years, which correspond to deep anestrus, recently weaned and isolated from the male.

Given that there are ewes with continuous reproductive activity where the adverse photoperiod does not have an effect, the hypothesis of this study was that the daughters of continuous ewes are not based on the photoperiod and begin their puberty during the anestrus, before the daughters of the seasonal ones, when the births occur out of season. The objective was to determine the beginning of the ovary activity in Pelibuey ewes born in autumn and winter to prove whether the daughters of ewes with continuous reproductive activity begin puberty before the daughters of seasonal ewes.

Material and Methods

Localization

The study was carried out in a research center located in the Mexican highlands, at 19 °N, with climate c(w)b(ij), semi-cold, semi-humid, summer rains, with rainfall of 800 to 1200 mm annually and average temperature of 19 °C (García, 1987).

Animals

The Pelibuey ewe lambs were eight daughters of continuous ewes (C) and eight daughters of seasonal ewes (S) born in autumn (November) and 21 ewe lambs (11C and 10S) born in winter (December-January). The ewe lambs were kept all the time with their mothers and were weaned at 90 d of age. The ewe lambs were maintained in an intensive system, fed with oats hay, maize silage, alfalfa hay, and commercial feed and mineral salts, according to their nutritional requirements. The ewe lambs remained totally isolated from contact with the males. Each week the weight and body condition was recorded, assigning point fourths in the scale from 1 to 5 (1 for emaciated and 5 for obese), based on Russel et al. (1984).

Blood sample drawing and processing

To identify the age at puberty of the ewe lambs, the beginning of the reproductive activity was determined through progesterone measurements in plasma, weekly in 3 mL of blood, extracted by jugular puncture, in vacutainer tubes that contained heparin as anticoagulant. Before 1 h of having drawn them, the samples were centrifuged at 1000 x g for 10 min. The separated plasma was deposited in vials and kept at 20 。C until their analysis.

Progesterone was quantified in the blood plasma with the technique of radioimmunoassay in solid phase, validated in sheep (Padmanabhan et al., 1995), with a commercial kit (Coat-A-Count®, Siemens). The coefficients of intra-assay and inter-assay variation were 5.5 and 4.81 %. The analytical sensitivity was 0.2 ng mL-1 (0.06 nmol L-1). The sampling began when the ewe lambs were approximately 4 months of age. The first ovulation was considered when the progesterone concentration was equal or higher than 1 ng mL-1 in each sample (Light et al., 1994).

Statistical analysis

In the study the differences in the presentation of puberty between daughters of continuous ewes and seasonal ewes in each birthing season (autumn or winter) were evaluated, in the variables age, weight, body condition at first ovulation, and differential of weight at weaning-weight at first ovulation (DPDP1aov), understood as the weight gained since the weaning of ewe lambs until the first ovulation (weight at first ovulation, minus weight at weaning). SAS (2002) was used for the analysis of variance according to the following model:

where yijk is the study variable (age, weight, body condition and differential of weight at weaning-weight at first ovulation), µ is the general mean, τi is the activity (continuous or seasonal), Ej is the time of year (autumn or winter, with different number of observations), and εijk is the experimental error.

Results and Discussion

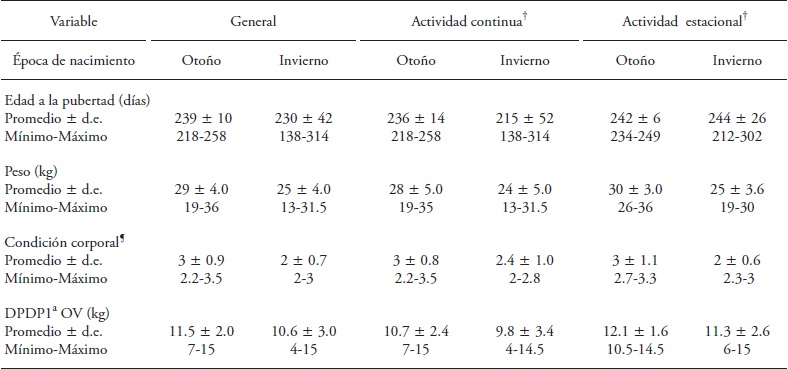

Among the ewe lambs, daughters of continuous ewes and seasonal ewes, there was no difference in the age at puberty, in any of the birthing seasons (p> 0.05; Table 1).

Table 1 Age, weight, body condition and differential of weight at weaning minus weight at first ovulation (DPDP1aOV), in Pelibuey ewe lambs born in autumn or winter, from mothers with seasonal or continuous reproduction.

† Reproductive pattern of the mother. ¶ Scale (1-5).

All the ewe lambs in the study were born out of season, so it was assumed that the daughters of ewes with continuous reproductive activity would reach puberty before the daughters of seasonal ewes, since these would not respond to the photoperiodical signals. Besides, the anestrus, which normally happens in the spring, and the season when they would be reaching puberty would not affect them. The results indicated that the age at which the Pelibuey ewe lambs would reach puberty, is independent of the capacity of their mothers to present seasonal or continuous reproductive activity, since there was no difference in this variable in the lamb groups or among those born in autumn and in winter. This is possibly because in both groups they responded similarly to the photoperiod. The characteristic of reproductive continuity is expressed mostly in adult ewes than in pre-lambing ewes (Valencia et al., 2006) and apparently is not expressed in the prepubescent.

It was relevant that in this study puberty came about at between 230 and 239 d, similar to what was documented in studies outside the reproductive season (239 days, Álvarez and Andrade, 2008; 231 days, Zavala et al., 2008), where the beginning of puberty was determined with the manifestation of heats and the help of males, which stimulate the females that have puberty ahead of time (Álvarez and Andrade, 2008).

Sheep of native breeds from temperate countries (Suffolk) reach puberty in the autumn of the same year when the ewe lambs are born in the spring (normal season of births), insofar as they have the adequate somatic development; those born in autumn wait for the short days in the following autumn for this to happen, even when they have reached the age and the adequate weight during the spring (Karsch et al., 1984). That is, ewe lambs have to be exposed first to long days (spring-summer) and then to short days for puberty to take place (Foster et al., 1985).

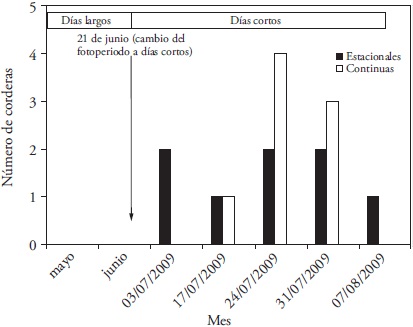

In this study, the ewes were exposed at 6 moths to an increase in the natural photoperiod (December 21 to June 21). An interesting finding is that the speed at which puberty presented itself starting in June 21, which is when the days become shorter, since most of the ewe lambs born in autumn (94 %) ovulated in July (Figure 1). Therefore, between 12 and 48 d, since the change in the photoperiod's direction, were enough for puberty to happen and in a notably synchronic manner. In fact, three of the ewe lambs born in winter ovulated before the summer solstice, so they only need exposure to long days (Figure 2). Something similar to what happens in Pelibuey lambs were present in D'man sheep (subtropical breed from Morocco), which do not require the change in the photoperiod of long days to short days for puberty to begin (Lahlou-Kassi' et al., 1989).

Figure 1 Relation of the number of ewe lambs with the date of the first ovulation (date at puberty), in ewe lambs that are daughters of ewes with continuous and seasonal reproductive activity, born in autumn.

Figure 2 Month from beginning of ovulation in ewe lambs born in winter, daughters of Pelibuey ewes with continuous and seasonal reproductive activity. Three ewe lambs cycled before the days began to shorten (June 21).

The results indicated that some Pelibuey lambs, such as the D'man sheep, did not require long days followed by short days to present puberty or react rapidly to the change in the photoperiod, from long days to short days, such as ewe lambs born in autumn (Figure 1). Álvarez and Andrade (2008) observed that Pelibuey ewe lambs reached the puberty in April and May, at an age similar to the one observed in our study, and they also didn't need to be exposed to short days.

It is possible for Pelibuey ewe lambs that do not respond to the change in photoperiod of the body weight to be the most important signal for puberty to begin. In contrast, other seasonal breeds require the stimuli of changes in the photoperiod and the body weight to attain puberty (Foster et al., 1985).

Conclusions

The age for puberty in Pelibuey ewe lambs is independent of the reproductive pattern (seasonal or continuous) of their mothers, both groups probably respond equally to the photoperiodic stimulus and the seasonal reproductive behavior is the characteristic that is expressed in the life of the adult sheep. There are Pelibuey ewe lambs capable of expressing puberty without the stimulus of a change from long days to short days being necessary for this.

Literatura Citada

Álvarez L., y S. Andrade. 2008. El efecto macho reduce la edad al primer estro y ovulación en corderas Pelibuey. Arch. Zootec. 57: 91-94. [ Links ]

Arroyo L., J., J. Gallegos S., A. Villa-Godoy, J. M. Berruecos, G. Perera, and J. Valencia. 2007. Reproductive activity of Pelibuey and Suffolk ewes at 19° north latitude. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 102: 24-30. [ Links ]

Cambellas J., B. 1993. Comportamiento reproductivo en ovinos tropicales. Rev. Cient. Luz. 3: 135-141. [ Links ]

De Lucas J., E. González-Padilla, y L. Martínez. 1997. Estacionalidad reproductiva de ovejas de cinco razas en el altiplano central mexicano. Téc. Pecu. Méx. 35: 25-31. [ Links ]

Dýrmundsson O., R. 1981. Natural factors affecting puberty and reproductive performance in ewe lambs: a review. Livest. Prod. Sci. 8: 55-65. [ Links ]

Foster D., L., and L. Jackson. 2006. Puberty in the sheep. In: Knobil, E., and J. D. Neill. (eds). The Physiology of Reproduction. 3rd Ed. Academic Press, New York. U.S.A. pp: 2127-2176. [ Links ]

Foster D., L., D. H. Olster, and S. M. Yellon. 1985. Neuroendocrine regulation of puberty by nutrition and photoperiod. In: Flamigni C., S. Venturoli, and J. R. Givens. (eds). Adolescence in females. Year Book Medical Publ. Chicago, III. U.S.A. pp: 1-21. [ Links ]

García E. 1987. Modificaciones al Sistema de Clasificación climática de Köppen. 4a ed. Instituto de Geografía, UNAM, México. 217 p. [ Links ]

Hafez E., S. E. 1952. Studies on the breeding season and reproduction on the ewe. J. Agric. Sci. 42: 189-265. [ Links ]

Hanocq E., L. Bodyn, J. Thimonier, J. Teyssier, B. Malpaux, and P. Chemineau. 1999. Genetic parameters of spontaneous spring ovulatory activity in Mérinos d'Arles sheep. Genet. Sel. Evol. 31: 77-90. [ Links ]

Karsch F., J., E. L. Bittman, D. L. Foster, R. L. Goodman, S. J. Legan, and J. E. Robinson. 1984. Neuroendocrine basis of seasonal reproduction. Rec. Prog. Hormone. Res. 40: 185-231. [ Links ]

Lahlou-Kassi' A., Y. M. Berger, G. E. Bradford, R. Boukhliq, A. Tibary, L. Derqaoup, and I. Boujenane. 1989. Performance of D'Man and Sardi sheep on accelerated lambing I. Fertility, litter size, postpartum anoestrus and puberty. Small Rumin. Res. 2: 225-239. [ Links ]

Light J., E., W. Silvia, and R. Reid. 1994. Luteolytic effect of prostaglandin F2 alpha and two metabolites in ewes. J. Anim. Sci. 72: 2718-2721. [ Links ]

Padmanabhan V., N. P. Evans, G. E. Dahl, K. L. McFadden, D. T. Mauger, and F. J. Karsch. 1995. Evidence for short or ultrashort loop negative feedback of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion. Neuroendocrinology 62: 248-58. [ Links ]

Roldán R., A., L. Zarco, J. M. Berruecos, y J. Valencia. 2014. Identificación de ovejas Pelibuey con actividad reproductiva continua. In: Memorias del XIV Congreso Panamericano de Ciencias Veterinarias. 6-9 de octubre. La Habana, Cuba. Archivo digital sin páginas. [ Links ]

Russel A. 1984. Body condition scoring of sheep. In Practice 6: 91-93. [ Links ]

SAS. Costumers support (computer program) versión 9.0 NC (USA): SAS Institute Inc., 2002. [ Links ]

Valencia J., J. M. Berruecos V., L. Zarco, H. Pérez R., y A. Roldán R. 2010. Métodos de selección de ovejas Pelibuey con actividad reproductiva continua. In: Memorias del XXXIV Congreso Nacional de Buiatría. Asociación de Médicos Veterinarios Especialistas en Bovinos. 6 de agosto. Monterrey, Nuevo León. pp: 220. [ Links ]

Valencia J., A. Porras, O. Mejía, J. M. Berruecos, y L. Zarco. 2006. Actividad reproductiva de ovejas Pelibuey durante los meses del anestro: influencia de la presencia del macho. Rev. Cient. Luz. 16: 136-141. [ Links ]

Valencia Z., M., and E. Gonzalez-Padilla. Pelibuey sheep in Mexico. 1983. In: Fitzhugh H., A., and G. E. Bradford (eds). Hair Sheep of Western Africa and the Americas. Westview Press, Boulder Colorado. pp. 55-73. [ Links ]

Zavala E., R., J. R. Ortiz O., J. P. Ugalde R., P. Montalvo M., A. Sierra V., y J. R. Sanginés G. 2008. Pubertad en hembras de cinco razas ovinas de pelo en condiciones de trópico seco. Zootecnia. Trop. 26: 465-473. [ Links ]

Received: February 2015; Accepted: November 2015

text in

text in