Introduction1

Insecurity is a topic relevant to us all and, in particular, to Latin America where there are the highest homicide rates in the world and where we can find the most violent cities (Chioda et al., 2016) . Only in Mexico, 64.5 per cent of the population of 18 years of age and more manifest as their main concern the issue of insecurity and crime; 79.4 per cent believe that living in their state is unsafe and, in 2018, 35.6 per cent of households had a victim of crime among its members (INEGI, 2019). Internationally, in the academic literature, one of the most stable predictors of crime has been poverty and this link has been particularly strong in urban enclaves (McCall et al., 2010; Wilson, 2012) .

Cities are the places with higher prevalence of violent crime; therefore, they are also the places where, mainly, citizen security is defined and where strategies to prevent violence are usually implemented (Muggah et al., 2016) . Synthesis of the literature suggests that the most effective interventions to reduce community violence occur in selected urban environments and target groups of low-income youth who exhibit antisocial risk behaviours; and shows that, among the most effective strategies, there is the dissolution of poverty concentration (USAID, 2016). A large part of these interventions is directed toward the reduction of singular aspects of urban poverty, such as economic inequality, youth unemployment, lack of opportunities in young people, weakness of security institutions and participation in criminal groups financed by the organized crime (Muggah, 2015). Therefore, the relation between poverty, insecurity, and urbanization has been studied extensively and it is considered an almost indissoluble link (Massey, 2013) .

However, there is evidence that this link does not always appear, neither everywhere, nor under the same conditions. Although there are arguments that show the historical decline in violence in developed countries around the world (Pinker, 2011) , in Latin America the rates of economic growth in the first decade of this century were not accompanied by significant declines in crime and violence (Chioda et al., 2016) . Again, take Mexico as an example, where indigenous communities, mostly rural, more effectively resisted the onslaught of organized crime because of their governance structures (Ley et al., 2019) . Likewise, in cities such as Medellín, Colombia, while its urbanization increased, its homicide rates decreased by 85 per cent, without the causes being known with precision (Muggah et al., 2016) . Outside of Latin America, Amartya Sen (2008) also points out discrepancies in the link between these variables in his reflection on the low levels of crime in Calcutta, one of the poorest cities in India. In the USA, the historical decline in crime was more drastic in the poorest neighbourhoods, but it is in those same neighbourhoods where crime rates are still the highest (Friedson and Sharkey, 2015) . This implies that, even when poverty and violence diminish, both continue to concentrate more, but in fewer places (Stretesky et al., 2004) . Even when this link has been proven repeatedly and in different ways, urban poverty has other determinants, and poverty is not enough to explain the variations of the many crime indicators.

Urban poverty is both a determinant of crime and a consequence. Crime causes higher levels of poverty by decreasing household income and assets (Grogger, 1997; Huang et al., 2004; Carter and Barrett, 2006) . It also impoverishes contexts by restricting the school, social and economic dynamics of communities, which in turn concentrates disadvantages of its inhabitants, erodes opportunities for social mobility, and generates criminogenic environments where victims and perpetrators of violent crime are found (Sampson, 2012) . Dynamic longitudinal analyses of the relationship between crime and poverty indicate that there are reciprocal effects in which poverty increases crime, but crime also makes neighbourhoods less attractive —by driving stores away and attracting lower-income residents— and so poverty increases (Hipp, 2010) . Violent crime can reverse the gains in development achieved in other areas, such as education, health or employment, and this is how it helps perpetuating poverty traps (Diprose, 2007) . The difficulty of living secure implies inadequate development processes that lead to a restriction of people's abilities (Sen, 2001) while differentials in capacities limit their agency to exploit the possibilities of their environment (Samman and Santos, 2009).

Multidimensional poverty measurements are an effective instrument to reflect the experience of poverty —such as social deprivation which is not income based— therefore, their use has increased in various countries around the world, allowing better policy strategies to reduce it (Alkire et al., 2014) . At the same time, qualitative studies show that violence is a constant concern of the population and one of the reasons that make it difficult to escape from poverty, since it represents a reduction in the freedom of people to decide and effectively use the institutional resources of their environment (Naraya et al., 2000). However, violence is not usually a dimension in poverty measurements, despite some recommendations for incorporating it (Diprose, 2007) . In addition, measurements of multidimensional poverty tend to assume that the determinants of poverty are the same in urban and rural environments (Teruel, 2014) , which is unsustainable in the case of crime.

A systematic review of the literature on the mechanisms that link poverty and crime was conducted in order to show the multiple ways in which this relationship is expressed in urban environments. The results help to justify the utility of including crime in multidimensional measurements of urban poverty. The findings also show the difficulties for an adequate measurement and the limitations of empirical research to sustain it. Policy implications of its inclusion are discussed at the end.

Methodology

The means to study the link between urban poverty and crime was a systematic review of the literature (Khan et al., 2017) . The question that structured the selection of articles was “by which mechanisms does crime increase or maintain the lack of development or welfare in urban areas?”. The search strategy sought to identify empirical articles whose independent variable were crime and the dependent variable poverty. The binomial that structured the search was “poverty and crime”.2 The terms chosen could be in the title, the summary or within the keywords of academic articles published since 1997 and included in the Web of Science database.3

The search yielded an initial total of 1,505 articles. After two researchers and two research assistants reviewed the title and the summary of each one of them, 1,365 articles were excluded. The next step consisted in a thorough review and classification of the 140 articles selected and then eighty-one more were excluded because they did not help answer the research question. After both revisions, fifty-nine articles were selected because they identify some mechanism that linked poverty and crime, regardless of the direction of the link between these two terms. By extending the inclusion criteria we intend to show the complex and bidirectional relations between both variables.

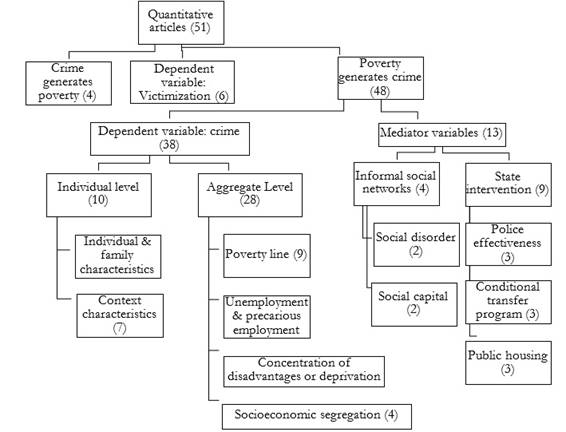

Once relevant information of the fifty-nine selected articles was classified, a thematic coding of the main findings was carried out. The numbers that appear in parentheses reflect the count of articles that subscribe to that argument, which can be interpreted as a sample of the saturation level of that topic in the present literature review. Please note that some articles examine several topics, so they can be counted more than once. Diagram 1 presents a summary of the process (See Annex at the end).

Results

The most common types of crime in the fifty-nine reviewed articles were homicide, violent assault, and property robbery. Some articles operationalize crime as antisocial behaviour, administrative offences or incivilities that do not become serious crimes (five). In contrast, studies that focus on crime rates sometimes studied more than one, either in isolation (eighteen) or with indices that group various types of crime (seventeen). Importantly, fifteen articles find differentiated effects by type of crime. Most of the literature was published in the United States of America (USA) (twenty-eight), Europe (nine) and Latin America (nine) and 86% of the articles used quantitative methods; see Diagram 2 at the end for the classification of quantitative articles. In quantitative articles, when the dependent variable was crime (thirty-eight), it was studied both at the individual level (ten) and at the aggregate level with crime rates (twenty-eight). An important heterogeneity was identified in the aggregate levels; researchers analysed relatively small areas or institutions, such as zip codes and census areas (four) or schools (four) and neighbourhoods (five), and larger areas using political demarcations, such as counties, municipalities (eight), cities, metropolitan zones (seven), and urban regions (five).

One of the most notable findings of the review was the order of the relationship between poverty and crime. Since the intention was to understand crime as a determinant of urban poverty, the research question sought crime as the independent variable. However, of the fifty-one quantitative articles —in which the order of the variables is explicit— only in four of them, the way in which crime generates poverty was studied. Among them, one of the articles that shows how violence impoverishes indicates —for Sweden— the most direct mechanism: that victimization reduces family income and therefore increases poverty (Nilsson and Estrada, 2003) . Another article explains that in the USA, a person with few economic resources is more likely to suffer an eviction from their home; but if this person also lives in a violent neighbourhood, then the probability of eviction is even greater than in peaceful neighbourhoods because some people intentionally stop paying rent as a savings strategy to move to a better neighbourhood (Desmond and Gershenson, 2017) . At the municipal level, in a province of Colombia, high homicide rates were associated with reductions in economic development; in 2005 alone, this reduction was equivalent to 7 per cent of gross domestic product (Cotte Poveda and Castro Rebolledo, 2014). Likewise, in Italy, high unemployment increases crime and this in turn reduces economic growth, causing a vicious circle that affects entire regions (Mauro and Carmeci, 2007) . A qualitative study complements these findings by highlighting that criminal participation leads to social stigmatization from official sanctions, which limits future opportunities, becoming a cumulative disadvantage (Nilsson et al., 2013).

The vast majority of selected quantitative articles use as a dependent variable an aspect associated with insecurity, but it is operationalized in two very different ways: as individual victimization (six) and as a crime (forty-eight). Surprisingly, only three articles studied the endogenous relationship between poverty and crime (Nilsson and Estrada, 2003; Mauro and Carmeci, 2007; Sachsida et al., 2010).

Among the reviewed articles, six of them have victimization as a dependent variable. In these articles, the main result was that being in a situation of poverty or disadvantage increases the probability of being a victim of crime, although one of the reviewed articles presents slightly different conclusions. A study from Finland shows that young people in poverty are more likely to suffer violent victimization (Aaltonen et al., 2016) . Likewise, another investigation that explored the effect of the 2008 economic crisis on victimization found that low-income people, as well as single mothers, are more likely to be victims of theft (Nilsson and Estrada, 2003) . Places of high concentration of poverty were also places of greater isolation, which facilitates theft (Griffiths and Tita, 2009) . A similar finding was made in metropolitan areas of Mexico in conditions of marginalization, in which households in poverty are more likely to be robbed (Caamal et al., 2012) . Even the “Moving to Opportunity” (MTO) experiment in Boston found that the relocation of young people living in poverty to higher-income neighbourhoods, exposed to less contextual violence, reduced their chances of victimization and improved their perception of security (Katz et al., 2001) . However, another study in Brazil found that the highest probability of victimization does not occur among the poorest, but in young people with medium income and higher education, who spend more time on public transport (Moura and Neto, 2015) .

Most of the selected quantitative articles focus on the ways in which poverty generates crime (forty-eight) —that is, they use poverty as an independent variable and crime as a dependent variable— and some of them emphasize the mediators of the association (thirteen). When the dependent variable referred to crime, it was studied both individually (ten) and at the aggregate level (twenty-eight).

Three of the ten articles that study crime as a dependent variable at the individual level sought to describe personal and family characteristics that, in association with environmental attributes, increase the probability of committing criminal behaviour and incivilities. An investigation explains that family characteristics such as low income, a family structure where the father is absent and describing himself as African American or Latino, restrict residential options. In turn, residing in communities of extreme poverty increases exposure to contexts of social disorder, reduces family social capital, and increases the likelihood that young people will commit a violent crime (De Coster et al., 2016) . Another study confirms that, when poor families have a perception of their community as inadequate for their children, if the community also has a high concentration of disadvantages, then, the probability of criminal involvement via incivilities is greater (Hay et al., 2016) . Another study details that individuals with low incomes and who live in places of low economic segregation are more likely to commit property crimes because they constantly interact with individuals with higher incomes, which allows them to observe their assets and to plan the theft. On the other hand, low-income individuals in places with high spatial segregation are more likely to commit violent assaults since they depend on the opportunity to commit a crime (Bjerk, 2010) .

Some articles directly estimated which characteristics of residential contexts increase the probability of incurring in criminal behaviour (seven). The characteristic of neighbourhoods that was most frequently associated with criminal involvement was the concentration of disadvantages4 (four) (Hannon, 2002; Hay and Evans, 2006; Weijters et al., 2009; Graif, 2015) . Another study pointed out that the disadvantages most associated with crime, at least in Germany, are unemployment and economic inequality (Entorf and Spengler, 2000) . A key finding of the MTO shows that the relocation of low-income individuals to higher-income neighbourhoods in multiple cities in the USA decreased the number of arrests for violent crime (Ludwig et al., 2001) . A more detailed study, also from the MTO, shows that ten years after relocating low-income women, arrest rates for violent crime fell by 33 per cent and property theft rates decreased by 32 per cent, with respect to a control group (Sciandra et al., 2013) . However, the trajectories of men were different. Two years after the relocation, arrests for violent crime in men fell by 34 per cent and property theft was equal to the control group, but ten years after the relocation the result was reversed and men increased arrests by 32 per cent for property crime and no differences were found with the control group regarding violent crime (Sciandra et al., 2013). A qualitative study highlighted that the internalization of the lack of opportunities and social mobility means that the inhabitants of marginalized areas prioritize individualism as a strategy to get ahead, which may explain criminal participation (Bryerton, 2016) .

The causal mechanism between poverty and crime was studied, mostly, at an aggregated level (twenty-eight). In this type of studies, the poverty independent variables were grouped into four categories according to their operationalization: poverty line (nine), unemployment or precarious employment (five), concentration of disadvantages or deprivation (ten) and socioeconomic segregation (four).

Six articles studied the ways in which a certain percentage of people below the poverty line were associated with increases in crime. It was identified that the combination of greater poverty and less police presence resulted in higher rates of property theft but not in violent crime; the latter is associated more with inequality and not with poverty (Kelly, 2000) . More specifically, a study in Colombia did not find a relationship between crime and inequality; rather, it identified that only part of the distribution of income is responsible for explaining the crime of property, since criminals are recruited from the lowest 20 per cent of the income distribution (Bourguignon et al., 2003) . However, for Brazil it was found that inequality affects crime measured in homicides, rather than poverty (Sachsida et al., 2010). The same mechanism, but in an inverse manner, shows that the increase in the income of the population reduces the crimes of robbery and homicides in the place of the increase, but the effect also reaches the surrounding neighbourhoods (Urrego et al., 2016) . These effects were found even when this mechanism was explored at the city level. When cities have an increase in their average income, a decline in crime is observed ten years later (Hipp and Kane, 2017) . Only one article proposes the opposite mechanism, that is, it poses an urban dilemma in Peru: economic growth was accompanied by an increase in robberies. The article points out that the increase in GDP meant greater urbanization, but also greater inequality, which caused an increase in the rates of property theft, but not in homicide rates (Hernández Breña, 2016) .

A subset of articles compiled under the poverty-line category deserves special attention, since the expression of urban poverty is considered through the evictions associated with the 2008 housing crisis in the USA (Desmond and Gershenson, 2017) . A longitudinal study found that, in neighbourhoods where evictions are concentrated, social and physical disorder tended to rise, while informal social controls weakened, which was associated with higher rates of property theft, but not with violent assault (Jones and Pridemore, 2016) . Hipp also finds that, in cities where there were higher eviction rates, robbery and assaults increased. However, this association does not appear in all cities, though the effect was greater in cities with more economic inequality and low socioeconomic segregation (Hipp and Chamberlain, 2015).

An additional expression of aggregate poverty was presented in five articles in the form of unemployment and precarious employment. For example, in Colombia and England, the youth unemployment rate was associated with greater property theft (Bourguignon et al., 2003; Han et al., 2013) . Another group of articles points out that the types of labour markets are associated with greater crime. Precarious work in marginalized areas, understood as a few hours of work with low wages and in secondary sectors, such as agriculture, is related to violent assaults (Lee and Slack, 2008) . Other research found that, in metropolitan areas where occupations in the low-skilled service sector outperform manufacturing occupations, levels of violent assault and property theft are higher (Weiss and Reid, 2005) . Similarly, a study shows that improvement in working conditions reduces property crime rates and the effect is greater in sectors that employ low-skilled labour (Doyle et al., 1999) .

The most common operationalization of poverty in this literature and the most frequent predictor of different forms of crime was the index of concentration of disadvantages —sometimes called social deprivation— with ten articles. The most common finding is that a higher concentration of disadvantages is related to higher homicide rates (four) (Kubrin and Herting, 2003; Nieuwbeerta et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2009; De Coster et al., 2016) , usually accompanied by a higher population density (Becker, 2016; McCall and Nieuwbeerta, 2016) . In fact, the effect of the concentration of disadvantages on homicides tends to spread to other nearby communities if the social characteristics are similar (Mears and Bhati, 2006) . Moreover, the effect is not linear or exponential, but its effects are more severe when the rate of concentration of disadvantages is between 20 per cent and 40 per cent, that is, communities where there is extreme poverty are not communities with greater homicide rates (Hipp and Yates, 2011) . Some studies also relate the concentration of disadvantages with higher rates of assault and robbery (Messner et al., 2013) , but others do not find effects in these crimes (Stretesky et al., 2004) .

An area where one of the most interesting heterogeneous effects occurs is with respect to the conditions in which socio-economic segregation increases crime or decreases it, as in the previous discussion of Bjerk's study (2010) . Gentrification is a major factor in the composition of the neighbourhood. On the one hand, when a neighbourhood increases the value of the square meter, but the surrounding neighbourhood does not, then crime increases in the recently gentrified neighbourhood (Boggess and Hipp, 2014) . On the other hand, when it is a set of neighbourhoods that is gentrified, then crime decreases in the centre of the group but increases in the neighbourhoods that are on the border (Boggess and Hipp, 2014). It was also important to study the neighbourhoods that surrounded those with a concentration of disadvantages. For example, in the case of men living next to a poor neighbourhood, there was an increase in risk taking and criminal behaviour, because it is associated with greater social disorder, greater stress, lower perception of access to legitimate opportunities for success, and a greater access to join to criminal networks; whereas in women only risk-taking increased (Graif, 2015) . From another perspective, the residential segregation of families with the same educational level was associated, in Chile, with higher crime rates in cities (Arriagada and Morales, 2006) . This segregation was important because it increased social distance, worsened inequality, reduced social mobility and eroded both social cohesion and future equity perspectives (Arriagada and Morales, 2006). Along the same lines, a qualitative article highlighted that the patterns of spatial distribution of poverty constitute a mechanism of reproduction of violence and poverty that is based on local integration structures (Ortega, 2014) .

As shown in Diagram 2, the last group includes research whose emphasis is on the mediating variables of the relationship between poverty and crime i.e. they examine variables that can reduce the effect of poverty on crime. One of these mediating variables is social disorder, which is theorized as an effect, first of all, of the concentration of disadvantages, but that later is a cause that explains the greater severity in the rates of criminal behaviour (Graif, 2015) and in violent assaults (Grubesic et al., 2012) . A reverse version of this mechanism is described with the variable of collective efficacy and similar concepts. The risk factors associated with criminal involvement are weakened in the presence of family social capital (De Coster et al., 2016) . At the aggregate level, greater social cohesion was also related to lower crime rates (Nieuwbeerta et al., 2008) .

A second grouping of mediator variables was related to government interventions that seek to break the connection between poverty and crime. The most evident is police effectiveness, which has been seen to reduce crime rates in general (Han et al., 2013) . An investigation shows that increased police activity decreases property crime but not violent assault (Kelly, 2000) . And another that studied the specific effect of the amount of raids (“clear-up rates”) confirmed that they reduce property theft and that the effect on assault is weak (Entorf and Spengler, 2000) . A qualitative study in Argentina emphasizes a reverse effect of the police, especially in places with violence, where the only presence of the state is the police apparatus. It shows how the treatment of the police contributes to increasing the environment of violence, which generates a vicious circle of confrontations, which in turn deteriorates the institutions that guarantee the rule of law, reduces access to the labour market and increases poverty (Auyero et al., 2013) .

The second effective intervention to reduce the connection between poverty and crime was conditional economic transfers. In the USA, a program that grants cash payments to families with children managed to reduce school dropouts, which was later associated with lower homicide rates (Hannon, 1997) . With the Bolsa Familia program in Brazil, an unexpected effect arose when, as conditional transfers increased, family income increased, which also caused a change in the formation of peer groups of young people and thus reduced crime (Chioda et al., 2016) . In Argentina, on the other hand, transfers in a program aimed at youth unemployment had a weak effect on crime; its effect was greater in property robbery, low in violent assaults and null in homicides (Meloni, 2014) .

The third government intervention is the concentration of public housing and has negative effects on crime. On the one hand, the residential relocation to poor neighbourhoods of the MTO increased the theft of property where there was a high residential concentration of vouchers owners, which suggests the advantages of the spatial dispersion of poverty (Hendey et al., 2016) . On the other hand, it was found that victimization is more likely in public housing due to isolation, the concentration of disadvantages and the ease of the opportunity for theft (Griffiths and Tita, 2009) . In Chicago, the destruction of public housing with high population density (“high rises”) reduced crime in those areas and in the surrounding ones. Although crime grew in the relocation sites, the increase was low, resulting in a cost-effective intervention (Aliprantis and Hartley, 2015) .

Discussion and policy implications

The systematic review shows multiple ways in which the connection between poverty and crime has been identified in the academic literature. Notably, only four quantitative articles explored the direction of crime toward poverty, but it is noteworthy that they coincide in their findings. The four affirm that crime has adverse economic implications, which are manifested in different ways —income and evictions— and at different levels —individual and regional—. This result complements the group with victimization as a dependent variable, whose main finding is that persons living in poverty, or amongst a concentration of disadvantages, have a higher likelihood of being a victim of a crime. Moreover, effective interventions aimed at reducing crime also focus on breaking its link with urban poverty; especially, the effect of conditional transfers evidences the existence of the connection (Chioda et al., 2016) , even if its effects may be weak (Meloni, 2014) . The triangulation of results, although still insufficient, shows key pathways on how crime might be a determinant of urban poverty.

A striking aspect of the systematic review was how little the term “urban” appeared. At best, the term population density was included as a statistical control to denote urban intensities, but these implications are rarely discussed directly. A superficial reading suggests that the urban environment is only the backdrop for the mechanisms described in the results section and that maybe the same would happen in rural settings. However, the omission of the urban has already been detected as a bias in Sociology as a discipline, in which it is only important to define rural sociology, since the rest is urban by default(Castells, 1976) . In the systematic review something similar happens because the urban is present in poverty by default in so far as it is not explicitly named; first, due to the selection of the articles themselves, but secondly, and more importantly, because the literature seeks to theorize the urban processes through which poverty is expressed in its links with insecurity. The urban is found in the form and implications of how poverty is operationalized. With the exception of studies based on poverty lines using only average income, the three urban poverty processes that, according to the results, are most associated with crime were the concentration of disadvantages, socioeconomic segregation, and social cohesion.

One of the clearest expressions of urban poverty, in its relation to crime, lies in the concentration of disadvantages —as Wilson (2012) already pointed out— which has clear interactions with other dimensions of poverty, such as low-quality schools, poor health, low salaries, and precarious employment in activities also associated with the city, such as those in the service sector. The concentration of disadvantages has eminently urban manifestations, such as the concentration of social housing, which generate unique dynamics of cities that result in criminogenic environments (Griffiths and Tita, 2009) . This mechanism is also closely linked to “social disorder” (Sampson and Raudenbush, 2004), which is another manifestation that only makes sense in urban environments and has been one of the main guides in the prevention of crime (Skogan, 2015) . The results reaffirm the axiom in criminology that high percentages of crime are concentrated in a few places, which has led to the most effective police intervention being focused on places of concentration of poverty and crime, commonly known as “hot spots” (Braga and Bond, 2008; Braga and Clarke, 2014).

A second urban process, directly related to the concentration of disadvantages, was residential segregation. Urbanization is also a process of allocation of resources that results in access to institutions of different quality, which questions the urban benefit over rural localities, as shown by the texts that discuss the role of police effectiveness (Auyero et al., 2013) . Residential segregation supposes, on the one hand, gentrification processes that concentrate resources and redistribute crime (Boggess and Hipp, 2014) and, on the other, mechanisms of social isolation that separate people from productive activities (Massey, 1990) and which in turn accelerate the impoverishment of neighbourhoods with higher eviction rates (Desmond and Gershenson, 2017) . Social isolation reduces opportunities for educational and labour mobility, increases economic inequality and facilitates the insertion in criminal networks. The spatial segregation of poverty could be one of the explanations behind the association between economic inequality and crime that have been found in multiple studies (Enamorado et al., 2016) . What relates the spatial segregation of poverty and the concentration of disadvantages is that violent crime is linked to opportunity structures characterized by the few institutional resources available to the inhabitants of these zones, suggesting the relationship is bidirectional (Elliott et al., 1996) .

Social cohesion —whether as social capital or as collective efficacy— is another urban process related to opportunity structures. The social cohesion of a bucolic rural community is very different from that of a dense megalopolis in which most of the interactions occur between anonymous people (Portes and Vickstrom, 2011). The way in which social (urban) capital is built has a direct link both in parental styles (Lösel and Farrington, 2012) , informal social controls (Sampson et al., 1997), and with the social norms of peer groups (Littman and Paluck, 2015) that originate criminal behaviour, especially among young people. Therefore, this can be a valuable path for crime prevention strategies.

The findings of the present literature review confirm the need of expanding research on the pathways between crime and poverty; if warranted, its inclusion in a multidimensional poverty measurement would be justified because crime implies an important restriction of freedom and abilities (Diprose, 2007) . The evidence is particularly strong at the community level, underscoring the bidirectional influence of crime and poverty in negatively shaping opportunity structures. This finding suggests that a spatial or territorial perspective could benefit poverty measurement by complementing individual and household approaches —levels for which the evidence is still scarce—. It is also worth noting that these results are not unidirectional nor absolute in a deterministic sense (i.e., criminogenic environments are not impoverishing to everybody in the community) and the ecological fallacy should always be a concern.

Among the measurement challenges, choosing a relevant measurement level is difficult because the community level is broadly defined. It matters because policy strategies and results differ depending on whether it is applied at the block, neighbourhood, or city level (Hipp, 2007) . Therefore, articles are not strictly comparable among themselves and depict different social dynamics that show the complexity of understanding the influence of poverty contexts and crime (Hipp and Steenbeek, 2016). The review revealed there is an empirical vacuum as to clarify the endogenous mechanisms that lead from crime to poverty (Hipp, 2010).

An additional measurement limitation is that the terms violence, insecurity and crime are used indistinctly, making it difficult to operationalize them. When searching the word “crime”, the low diversity of crimes that emerges is surprising. The results of the systematic review mainly identify as dependent variables homicides, violent assaults, and property robberies; that is, crimes with victims or predators, which are the ones that most concern the population, but are also the least frequent (Escalante, 2012) . Therefore, the present findings refer exclusively to violent and community crime, with victims, and not to the entire continuum of violence and illegality (Krug et al., 2002) . A second problem of the definition concerns the use of isolated crime indicators, such as the homicide rate, or an index, mixing robberies with violent assaults and homicides. The review shows that the determinants and mechanisms of one type of crime are not the same as those of another. Investigations that collapse multiple index crimes are likely to obscure these differences and, therefore, a poverty measure would have to select crimes or weigh them differently.

Lastly, the empirical literature has a strong bias towards high-income countries. It is striking that the regions with the highest levels of violence and poverty, such as Latin America, are not the places that generate the most literature. It may dispute the external validity of the findings for middle-income countries, where the types of violence and the institutional resources to confront it are very different. To this end, the recommendation is to prioritize research —especially rigorous qualitative studies— that explicitly sheds light on the multiple ways in which crime impoverishes people and urban contexts, especially in low and middle income countries. A key research agenda is to identify the exceptions to the general pathways described in the review, particularly the way crime created opportunity structures by providing jobs and infrastructure in some communities.

Conclusion

The review attests that the evidence of crime as a determinant of poverty in urban enclaves is insufficient and it would thus be premature to include crime as part of a multidimensional poverty measure. The academic literature on the field still needs to find a consensus on a definition of crime, the relevant measurement level, the key mechanisms that link them, and explanations for its exceptions.

Nonetheless, despite these significant challenges, the review shows that crime is a central aspect of the conditions and experience of poverty. The multidimensional paradigm assumes that the strategies for its reduction involve a better understanding of the concentration of social disadvantages, among which crime occupies a prominent place. For poverty measurement, it is promising to understand the economic consequences of victimization and of living in high crime environments. The complexity of harmonizing it with traditional ways of measuring poverty should not be a reason to avoid its inclusion but rather an incentive to improve the measurement of crime and to fill empirical gaps in the field. The results of this review aim to encourage novel and sophisticated poverty measurements that improve the identification of people and places whose living conditions require change to expand the population’s capabilities. Higher levels of poverty are not an attractive scenario for those responsible to end it, but it would better reflect the precarious living conditions of the population.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)