Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Convergencia

versão On-line ISSN 2448-5799versão impressa ISSN 1405-1435

Convergencia vol.23 no.70 Toluca Jan./Abr. 2016

Scientific Articles

Measurement and graphic representation of cultural distances between Latin American countries

1Universidad de Chile, Chile. pfarias@fen.uchile.cl

Despite the central role of cultural distances in social sciences, literature is surprisingly scarce in quantitatively measuring and graphically representing this concept in Latin America. This study addresses this issue calculating a cultural distance index using the nine cultural dimensions measured by House et al. (2004) for ten Latin American countries: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico and Venezuela. Also, this study graphically presents the cultural distances calculated. The relevance of this study is the ability to incorporate cultural indicators that allow comparing the current situation and prospects in Latin America. In order to illustrate the implications of this study, the case of cultural distances of Mexico with other nine Latin American countries is analyzed.

Key words: national culture; cultural distances; cultural dimensions; Latin America

Pese al rol central que tienen las distancias culturales en las ciencias sociales, la literatura es sorprendentemente escasa en la medición cuantitativa y representación gráfica de este concepto en América Latina. El presente estudio aborda esta cuestión al mostrar un índice de distancia cultural usando las nueve dimensiones culturales medidas por House et al. (2004) para diez países latinoamericanos: Argentina, Bolivia, Brasil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, México y Venezuela. También se representa gráficamente las distancias culturales calculadas. La relevancia de esta investigación radica en la posibilidad de incorporar indicadores culturales que permiten la comparación de la situación actual y perspectivas en América Latina. Con el propósito de ilustrar las implicancias de este estudio, se analiza el caso de las distancias culturales de México con los otros nueve países latinoamericanos.

Palabras clave: cultura nacional; distancias culturales; dimensiones culturales; América Latina

Introduction

The differences found in people from different countries in their ways of thinking, acting and reacting has a great impact in the different areas of the social sciences; it is because of this that the fact of being able to recognize, quantitatively measure and interpret the cultural differences among countries is of the utmost importance. The concept of cultural distance among these has been applied to a variety of research projects, including the effect of the cultural distance among countries in the behavior of immigrants and expatriate, international agreements between nations, social changes, foreign investment, international expansion, management of foreign subsidiaries, organizational transformation, consumer preferences, publicity formats effectiveness, use of the media and distribution channels, organizational learning, technology transferences, etc., (Shenkar, 2001; Manzur et al., 2012; Meunier and Medeiros, 2013; Olavarrieta et al., 2013; Farías, 2015).

Despite the main role cultural differences among countries play in the social sciences, the literature in regards to the quantitative measurement and graphic representation of this concept in Latin America is scarce. This study deals with this subject using nine cultural dimension measured by House et al. (2004) for ten Latin American countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, México and Venezuela) and using the methodologies suggested by Kogut and Singh (1988) and Fernández et al. (2003) to measure quantitatively and graphically represent the cultural differences among countries in Latin America.

This study presents a methodology to measure quantitatively and graphically represent the cultural differences among countries and project possible changes in the cultural distances among the ten Latin American countries included in the House et al. (2004) study. The relevance of this paper is the possibility of incorporating cultural indicators that allows the comparison of the current situation and the perspectives in Latin America. The paper is organized as follows: The second section describes the conceptual framework. Section three formally presents the methodology and the research results. In the fourth section, in order to illustrate the implications of this study, the case of the cultural differences in Mexico with the other nine Latin American countries is analyzed. Finally, in the fifth section, we present the conclusions and implications of this study for researchers and administrators.

Conceptual Framework

National Culture

Hofstede (1980) carried out, in the 1970s, one of the most complete studies that had been made to that date on the cultural differences between countries. The research was of great impact in several spheres of sociology and administration, especially in negotiation, management of international teams, and in the configuration of international marketing strategies (Hofstede, 2001; Hidalgo et al., 2007; Manzur et al., 2012). Hofstede (1980) analyzed 70 countries and simplified complex cultural behavior patterns in only four dimension (although currently Hofstede uses six cultural dimensions). The Hofstede's study has shown that there are cultural grouping at a national level that affect the behavior of societies and organizations.

According to Hofstede (1991: 4) , culture is always a collective phenomenon since it is shared with people who live, or lived, in the same social environment where such culture is acquired. Culture is acquired not inherited. This is derived from a social environment, not from genes. Culture can be differentiated from the human nature on one hand, and from the individual's personality on the other (see Figure 1 1). Hofstede (1991: 5) defines "culture" as the collective mental programming that distinguish members of a group, or category of people, from another.

Hofstede (2001: 2) mentions that the mental programs can be inherited (transferred through our genes) or that these can be learned after being born; similarly, he defines three levels of mental programming: individual, collective and universal. Hofstede mentions that at an individual level, at least one part of the programming must be inherited; otherwise, it is difficult to explain differences in the abilities and temperament between the children from the same family and environment. At a collective level, Hofstede (2001: 3) mentions that most of our mental programming is learned; this is exemplified with the Americans, who are a multitude of genetic variations, but nonetheless, they show a collective mental programming which is clearly perceived by foreigners. Hofstede (2001: 3) indicates that the universal level of the mental programming is shared by all human beings and it is related to the human nature. This is inherited through the genes, determining our basic physical and psychological functioning. The human capacity of feeling fear, anger, love, pleasure, hatred, etcetera, belong to this level of mental programming.

Hofstede (1991: 5) refers to group as the ensemble of people who are in contact with one another. A category of people consists on people who share something without being necessarily in contact. For instance, all executives, sportspeople, vegetarians, writers, philosophers, etc. This definition of culture refers more tangibly to consider the personal characteristics that are common and standard of a given society. Since there is a wide variety of individual personalities in any society, the one that is more frequently observed (statistically speaking) has been used to get closer to the national culture (Clark, 1990; Nakata and Sivakumar, 1996). The term "culture", in this sense, can be applied to nations, organizations, occupations and professions, religious and ethnic groups, etc.

The concept of culture is more applicable to societies than to nations. However, historically, many nations have developed themselves together, even if this consists on clearly differentiated groups, and even if there are less integrated minorities. Moreover, there are also "forces" that make integration difficult. For instance, there are religious or ethnic groups that strive to achieve their own identity. Nonetheless, inside the nations there have been "forces" that make integration possible; a dominant national language, common mass media, national educational system, national army, national political system, national representations in sports events, national markets of products and services, etc.

According to Hofstede (2001: 12) , the origin of the cultural distances between two nations is rooted in the universal history; he mentions that in some cases, the explanations of the causes of these cultural distances can be possible. In many other cases, one could simply assume that small differences that occurred hundreds and thousands of years ago, and which were transferred from generation to generation, gave way, after growing and growing, to the current cultural distances among countries.

House et al. (2004) study

House et al. (2004: 12) , incorporating the cultural dimensions of Hofstede (1980; 2001) and using qualitative methods, identified and measured nine cultural dimensions for 62 countries. House et al. (2004) work is also known as the GLOBE (Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness Research) project or study. In this paper, in order to present a methodology to measure quantitatively and graphically represent the cultural distances among the Latin American countries, the scores of the aforementioned countries in the nine cultural dimensions measured by House et al. (2004). In the ten Latin American countries included in House et al. (2004) study, a total of 1.527 medium level managers were surveyed (no Presidents nor vicepresidents and from two levels above workers). The interviewees were part of three business sectors: telecommunications, finance and the food processing industry.

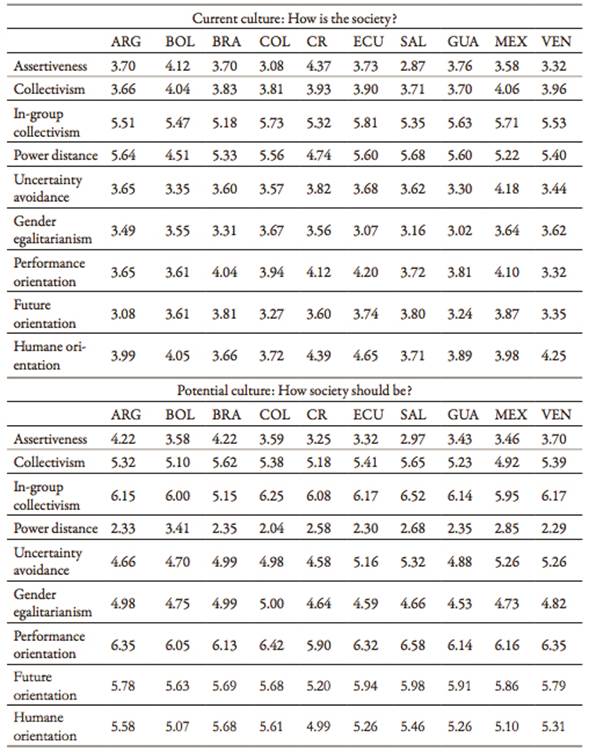

The ten Latin American countries included and the total surveys applied by House et al. (2004) are the following: Argentina (153), Bolivia (99), Brazil (265), Colombia (302), Costa Rica (114), Ecuador (49), El Salvador (25), Guatemala (110), México (260) and Venezuela (150). House et al. (2004: 11) measured nine dimensions of the national culture through the answers from the Latin American managers on how they wanted their culture to be in each one of the nine cultural dimensions (see Table 1).

The use of a relatively homogeneous sample (i.e. managers from middle level from three different business sectors) allows capturing the cultural dimensions more clearly in comparison to using a more heterogeneous sample in the different countries. The cultural dimensions measured proved to be unidimensional, with an adequate Cronbach alpha coefficient and with a strong capacity of social aggregation (House et al., 2004).

Cultural dimensions measured by House et al. (2004)

The House et al. (2004: 11) measured nine dimensions of the national culture: assertiveness, power distance, humane orientation, future orientation, in-group collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, gender egalitarianism, institutional collectivism and performance orientation. Here are each of these nine dimensions briefly described:

Assertiveness. House et al. (2004) made a difference between societies where people are quite aggressive, affirmative, of strong opinions, dominant and that uses physical force to settle their differences, from other less aggressive societies. For the traditional values of the world, this has to do with male and female cultures (Hofstede, 1980): being affectionate, soft, not aggressive is identified with the "feminine" temperament, and, on the other hand, more aggressiveness, dominant, physically present, opinionated, are identified with the "masculine" temperament.

Institutional Collectivism. This refers to the degree to which a society values group loyalty, the commitment to group regulations and collective activities, social cohesion and intense sociabilization above personal objectives, autonomy and privacy (Hofstede, 2001; Triandis, 2004).

In-group collectivism. This dimension tries to identify the orientation toward collective values in the relation of parents and children, and the importance of the family within the society.

Power distance. This dimension is defined as the degree to which a society accepts unequal distribution of power in institutions and organizations (De Mooij and Hofstede, 2002; Hodgetts and Luthans, 1993; Ryan et al., 1999). "Institutions", such as family, school and the community, are basic elements of a society. "Organizations" are social groups composed by people, tasks and administration that form a systematic structure of interaction relationships which usually produce goods or services or norms to satisfy a community's needs within an environment, and thus, achieve a distinctive purpose which is its mission (Hofstede, 2001).

Uncertainty avoidance. This refers to the degree to which members of a society feel uncomfortable in non-structured situations (Hofstede, 2001). Hofstede (1991) mentions that this dimension can also be defined as the degree in which people from a country prefer structured situations over non-structured situations. A society oriented to the reduction of uncertainty creates norms, laws, regulations and control measurements in order to decrease the amount of uncertainty (De Mooij and Hofstede, 2002; Lu et al., 1999; Shane, 1995). These rules could be written rules, but they can also be unwritten and imposed through tradition (Stohl, 1993). In these cultures, people strive for more structured situations, they want to know precisely what is going to happen, and therefore, forecasting of events is greatly valued (Ryan et al., 1999; Triandis, 2004).

Gender egalitarianism. This cultural dimension tries to identify to which point people from a country prefer to minimize the role and status differences between men and women.

Performance orientation. It is about identifying the degree to which people are oriented towards excellence, continuous betterment, to the obtaining of outstanding performance and the achievement of results.

Future orientation. This cultural dimension tries to identify whether individuals are oriented towards the future, or if the criteria and values are centered in the present or in the past.

Humane orientation. This dimension tries to identify the degree to which a country's cultural values support and reward this country's population for altruist, just, compassionate, friendly and sensible acts towards their fellow countrymen.

Study

Quantitative measurement of the cultural distances

In order to quantitatively measure the culture distances among the ten Latin American countries included in House et al. (2004) , in this study the methodology proposed by Kogut and Singh (1988) was used. They developed a cultural distance index for the cultural dimensions measured by Hofstede (1980) . Kogut and Singh (1988) combined the cultural dimensions of Hofstede (1980) in an added cultural distances among countries measure. Such measure has been widely used in other research projects in different areas of the social sciences (e.g., Agarwal, 1993; Barkema et al., 1996; Roth and O'Donnel, 1996). This index is created from the deviations average of the indexes (I) between country "X" and country "Y" in each one of the cultural dimensions "i", corrected by the variance "V" of each cultural dimension "i" (Kogut and Singh, 1988: 422). Algebraically, the index of "cultural distance" between country "X" and country "Y" (Cultural Distance - CDxy) for the House et al., (2004) nine cultural dimensions study, it can be calculated with the following equation 1:

Table 2 shows the matrices of the cultural distances calculated in this study for the ten Latin American countries included in House et al., (2004) study. The cultural distances currently present in the ten Latin American countries are presented (matrix of current cultural distances) and also the cultural distances that these ten countries may have in the future (matrix of potential cultural distances).

Distancing- closeness of the national cultures

The differential of how people live and how they would like to live is a dissatisfaction factor, and therefore, of cultural change. Given the difference between how people live (matrix of current cultural distances) and how they would like to live (matrix of potential cultural distances) in Latin America, the efforts to decrease this differential will be an important cultural changes trend in the future (House et al., 2004). Table 3 indicates the percentage of potential increment in the cultural distance among the ten Latin American countries. Positive values (negatives) indicate the existence of a potential cultural distancing (closeness) among the countries. For example, Brazil and El Salvador show a relevant cultural distancing potential (the cultural distance would increase in 421.3%, since Brazilians and Salvadorians differ in the national culture they would like to achieve in the future. On the other hand, the Ecuadorian and Venezuelan national cultures present a relevant potential closeness in the upcoming decades (the cultural distance would be reduced in 85.1%). As a consequence, it can be projected which national cultures will become more distant and which will become closer, this for each of the ten Latin American countries.

Graphic representation of the cultural distances

Using as entry variables the cultural distances calculated among the ten Latin American countries (current and potential cultural distances matrices; see Table 2), two multi-dimensional escalations were created (MDE) in order to represent graphically these cultural distances in maps. Figure 2 (MDE; Stress = .09417; RSQ = .95240; acceptable adjustment indices, Malhotra, 2004; Hair et al., 2006) presents the map of the current cultural distances among the ten Latin American countries, using data from the current cultural distances matrix.

Stress measures the maladjustment or the proportion of the data variance of an optimal scale that the MDE does not explain. A 0.20, or higher, Stress is considered as bad, 0.05 is considered as good, and 0.025 is seen as excellent. (Malhotra, 2004: 617-618) . RSQ (square R) shows the proportion of the variance of the data of an optimal scale that can be explain using the MDE. Values of 0.60 and higher are considered acceptable (Malhotra, 2004: 617). Figure 3 (MDE; Stress = .06359; RSQ = .97679; acceptable adjustments indices, Malhotra, 2004; Hair et al., 2006) present the map of the potential cultural distances found among the ten Latin American Countries, using the data from the potential cultural distances matrix.

In both cultural distances maps it can be observed that Brazil shows a small cultural difference with Argentina and Colombia. On the other hand, Brazil presents a great cultural distance with Mexico and Ecuador. In both cultural distances maps it can be observed that Mexico shows a small cultural difference with Ecuador. In contrast; Mexico shows a great cultural distance with Argentina and Brazil (see Figures 2 and 3).

Interpretation of the dimensions of the cultural distances maps

Later, the methodology suggested by Fernández et al. (2003) was followed to interpret the dimensions of the maps obtained in the MDE. As a consequence, a linear regression was done for each of the nine cultural dimensions, this is, the dependent variable is the index value (I) of the cultural dimension ("i") for each country "X" and the independent variables are the MDE (Dim1, Dim2) for each country "X" (see equation 2). According to Fernández et al. (2003), the condition for a satisfactory interpretation lies in the fact that the coefficients (beta) are statistically significant (value -p < 0.01) and a square R of 0.70 is considered as acceptable.

For the current cultural distances MDE, the results of Table 4 indicate with a statistical significance that dimension 1 is explained mainly by the collectivism variables (negatively) and power distance, and dimension 2 is explained, principally, by the power distance variable (negatively). Therefore, it is possible to observe that the current cultural distance Costa Rica and Bolivia present in comparison to the rest of the Latin American countries can be explained by the little power distance as well as by the high collectivisms shown.

For the potential cultural dimensions MDE, the results of Table 5 indicate with a statistical significance that dimension 1 is explained mainly by the human orientation, future orientation and performance orientation, and dimension 2 is explained, above all, by the human orientation and genre egalitarianism. The adjustments for the future orientation (value-p = 0.012) were considered as acceptable and genre egalitarianism (R square = 0.697) when it was observed that these values are very close to the acceptable values (value-p < 0.01 and R square > 0.7), according to Fernández et al. (2003). Then, it is possible to observe that the individuals from Argentina, Brazil and Colombia present a stronger desire of having a human orientation and more genre egalitarianism, which would take these countries, in the future, to a potential cultural distancing from the rest of the Latin American countries.

Analysis of Mexico's case

In this section the case of Mexico is analyzed in order to illustrate the implications of this study for the ten Latin American countries. Figure 4 shows the Mexico's current and potential cultural distances in relation to the other 9 Latin American countries. This work shows that nowadays Mexico portraits a large cultural distance with Argentina, Guatemala and El Salvador. In contrast, currently Mexico presents a small cultural difference with Costa Rica and Ecuador. Moreover, it is possible to observe that Mexico a potential cultural distancing with Brazil (the cultural distance would increase to 66.2%) and a potential cultural closeness with Guatemala (the cultural distance would decrease to 76.3%).

Current and potential cultural distances with other countries have implications in the development of Latin America and particularly of Mexico. For instance, it has been observed that the cultural distance may have an influence on commercial exchange between countries (Lee, 1998). More similar cultures may generate more agreements, relations, common behavior this facilitating the commercial exchange between countries. Using information from the SE (2005), the association between the current social distance and the growth in the exports from Mexico to the nine Latin American countries in the last ten years (2004-2014).

Figure 5 shows that the countries that currently have a shorter cultural distance with Mexico (e.g. Brazil, Colombia) present higher growth in the exports from Mexico during the last ten years. On the other hand, countries with more cultural distance (e.g. Argentina, Guatemala, El Salvador, Venezuela) register a lower increase in exports from Mexico during the last decade.

A shorter cultural distance between countries can also facilitate immigration between countries (Tadesse and White, 2010). Using information from the INEDI (2015) (National Institute of Statistics and Geography) the association between the current cultural distance and growth in the period between 1970 and 2010 in the number of immigrants arriving in Mexico from the other nine Latin American countries. Figure 6 shows that the countries which currently have a shorter cultural distance with Mexico (e.g. Colombia) present a higher growth rate in the number of immigrants arriving in Mexico between 1970 and 2010. In contrast, countries with more cultural distance (e.g. Guatemala) present a lower growth rate of immigrants arriving in Mexico during the same period.

Since culture does have an influence on research teams (Kedia et al., 1992), which are characterized by having a long-term scope when working and defining research lines, the potential cultural distance between countries can have an influence the number of scientific co-publications among research groups from different countries. Research teams from countries with a more pronounced potential cultural distance may be more attractive given the potential cultural differences for the research groups from a certain country due to the difference among researchers, test units, contexts, etc.

With information from Lozano et al. (2006) , the association between the potential cultural distance and the number of scientific co-publications among research groups from Mexico with research groups from the other nine Latin American countries. Figure 7 shows that those countries with a more pronounces cultural distance with Mexico (e.g. Brazil) present a larger number of scientific co-publications in Mexico. In contrast, those countries closer in terms of the cultural distance to Mexico (e.g. Bolivia, Guatemala) have a smaller number of scientific co-publications in Mexico.

It is important to mention that in this section, the associations between variables are described, this in order to illustrate the implications of this research project. Future research in Latin America may incorporate control variables that allow draw a conclusion on the causality of the analyzed variables or other variables the researcher may want to examine.

Conclusions and implications

This research deals with the quantitative measurement and graphic representation of the cultural distances among ten Latin American countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, México and Venezuela), using the nine cultural dimensions measured by House et al. (2004) for these ten Latin American countries and using the methodologies proposed by Kogut and Singh (1988) and Fernández et al. (2003) , to measure quantitatively, graphically represent and interpret the cultural distances among countries in Latin America.

This study will allow working quantitatively the cultural distance variable among Latin American countries, which a large number of international research projects has been traditionally tackled qualitatively (for a revision of the mentioned projects see Alasuutari, 1995). This will make it possible to have a different approach to future research in Latin America, where the cultural distance among countries may be included in the analysis. Therefore, the implications of this work are numerous for the researchers from different areas of the social sciences: a methodology to quantitatively measure and graphically represent the cultural distances and project possible changes in the cultural distances among the ten Latin American countries included in House et al. (2004) .

Researchers from a wide diversity of areas of the social sciences can use the cultural distances calculated as entry variables in models that incorporate this concept, whether as a dependent variable, independent variable or control variable, in future research projects in Latin America. The quantitative measurement and graphic representation of the cultural distances among the ten Latin American countries could be used not only in quantitative approaches, but also in qualitative ones by using the results of this study as secondary data for the elaboration of research questions, understand the results of a research, etc.

Regulators, managers and administrators can also use this tool to make a decision taking into account the cultural distances among Latin American countries. It is expected that in the future, both decision-makers and researchers have studies at hand which, using comparable methodologies, incorporate in their analysis a larger number of Latin American countries (i.e. not only the ones included in House et al., 2004) , in order to evaluate the evolution of the cultural distances among Latin American countries and their potential impact in different areas of the social sciences.

REFERENCES

Alasuutari, Pertti (1995), Researching culture: Qualitative method and cultural studies, London: Sage. [ Links ]

Agarwal, Sanjeev (1993), "Influence of formalization on role stress, organizational commitment, and work alienation of salespersons: A cross-national comparative study", en Journal of International Business Studies, vol. 24, núm. 4, England. [ Links ]

Barkema, Harry et al. (1996), "Foreign Entry, Cultural Barriers and Learning", en Strategic Management Journal, vol. 17, núm. 1, Holland. [ Links ]

Clark, Terry (1990), "International Marketing and National Character: A review and proposal for an integrative theory", en Journal of Marketing, vol. 54, núm. 4, USA. [ Links ]

De Mooij, Marieke y Geert Hofstede (2002), "Convergence and divergence in consumer behaviour: implications for international retailing", en Journal of Retailing, vol. 78, núm. 1, USA. [ Links ]

Farías, Pablo (2015), "Determinants of the success of global and local brands in Latin America", en RAE, vol. 55, núm. 5, Brazil. [ Links ]

Fernández, Pedro et al. (2003), "Mapas Perceptuales: Interpretación de Ejes del MDS Usando Regresión", en Documento de trabajo, Chile: Universidad Técnica Federico Santa María. [ Links ]

Hair, Joseph et al. (2006), Multivariate data analysis, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Hidalgo, Pedro et al. (2007), "La cultura nacional y su impacto en los negocios: El caso chileno", en Estudios Gerenciales, vol. 23, núm. 105, Colombia. [ Links ]

Hodgetts, Richard y Fred Luthans (1993), "U.S. multinationals' compensation strategies for local management: Cross-cultural implications", en Compensation & Benefits Review, vol. 25, núm. 2, USA: California. [ Links ]

Hofstede, Geert (1980), Culture´s Consequences: International Differences in work-related values, Beverly Hills, USA, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Hofstede, Geert (1991), Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, USA, CA: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Hofstede, Geert (2001), Culture´s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations, USA, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

House, Robert J. et al. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies, USA, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Kedia, Ben, Robert Keller y Scott D. Jullan (1992), "Dimensions of national culture and the productivity of R&D units", en The Journal of High Technology Management Research, vol. 3, núm. 1, Holland. [ Links ]

Kogut, Bruce y Harbir Singh (1988), "The effect of national culture on the choice of entry mode", en Journal of International Business Studies, vol. 19, núm. 3, England. [ Links ]

Lee, Dong-Jin (1998), "The effect of cultural distance on the relational exchange between exporters and importers: the case of Australian exporters", en Journal of Global Marketing, vol. 11, núm. 4, England. [ Links ]

Lozano, Rosa et al. (2006), "Indicadores de colaboración científica inter-centros en los países de América Latina", en Interciencia: Revista de Ciencia y Tecnología de América, vol. 31, núm. 4, Venezuela. [ Links ]

Lu, Long-Chuan, Gregory M. Rose y Jeffrey G. Blodgett (1999), "The effects of cultural dimensions on ethical decision making in marketing: An exploratory study", en Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 18, núm. 1, Germany. [ Links ]

Malhotra, Naresh K. (2004), Investigación de Mercados. Un Enfoque Aplicado, México: Pearson Educación. [ Links ]

Manzur, Enrique et al. (2012), "Comparative Advertising Effectiveness in Latin America: Evidence from Chile", en International Marketing Review, vol. 29, núm. 3, England. [ Links ]

Meunier, Isabel y Marcelo de Almeida Medeiros (2013), "Construindo a América do Sul: identidades e interesses na formação discursiva da Unasul", en Dados, vol. 56, núm. 3, Brazil. [ Links ]

Nakata, Cheryl y Kumar Sivakumar (1996), "National culture and new product development: An integrative review", en Journal of Marketing, vol. 60, núm. 1, USA. [ Links ]

Olavarrieta, Sergio et al. (2013), "Store Price Promotion Strategies, Price Perceptions, Search and Purchase Intentions", en Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, vol. 26, núm. 3, Colombia. [ Links ]

Roth, Kendall y Sharon O'Donnel (1996), "Foreign Subsidiary Compensation Strategy: An Agency Theory Perspective", en Academy of Management Journal, vol. 39, núm. 3, USA. [ Links ]

Ryan, Ann Marie et al. (1999), "An international look at selection practices: Nation and culture as explanations for variability in practice", en Personnel Psychology, vol. 52, núm. 2, USA. [ Links ]

Shane, Scott (1995), "Uncertainty avoidance and the preference for innovation championing roles", en Journal of International Business Studies, vol. 26, núm. 1, England. [ Links ]

Shenkar, Oded (2001), "Cultural Distance Revisited: Towards a More Rigorous Conceptualization and Measurement of Cultural Differences", en Journal of International Business Studies, vol. 32, núm. 3, England. [ Links ]

Stohl, Cynthia (1993), "European managers' interpretations of participation: A semantic network analysis", en Human Communication Research, vol. 21, núm. 1, USA. [ Links ]

Tadesse, Bedassa y Roger White (2010), "Cultural distance as a determinant of bilateral trade flows: do immigrants counter the effect of cultural differences?", en Applied Economics Letters, vol. 17, núm. 2, England. [ Links ]

Triandis, Harry C. (2004), "The many dimensions of culture", en Academy of management executive, vol. 18, núm. 1, USA. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

INEDI (2015), "Nacidos en otro país". Disponible en Disponible en http://www.inegi.org.mx/inegi/contenidos/espanol/prensa/contenidos/Articulos/sociodemograficas/nacidosenotropais.pdf [30 de agosto de 2015]. [ Links ]

SE (2015), "Información Estadística y Arancelaria". Disponible en Disponible en http://www.economia.gob.mx/comunidad-negocios/comercio-exterior/informacion-estadistica-y-arancelaria [1 de septiembre de 2015]. [ Links ]

Annex

Table 3: Potential Growth of Cultural Distance

Source: Own elaboration

Note: Positive values (negative) indicate that there is a potential cultural distancing (closeness) between both countries.

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 4: Potential and Current distances of Mexico in relation to 9 Latin American countries.

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 5: Current cultural distances and the growth of exports from Mexico to the 9 countries.

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 6: Current cultural distances and the number of immigrants from the 9 countries to Mexico

2All Figures and Tables are included in the Annex, at the end of this paper (Editor's note).

Received: October 11, 2014; Accepted: September 05, 2015

texto em

texto em