Introduction

Mexico is a mega-diverse country, and it is considered among the top five in the world in terms of species richness and endemism. Worldwide, it has a high diversity of flora and fauna and, therefore, one should expect to find also a great diversity of macromycetes; however, not enough studies exist of some regions of Mexico, in particular, in the state of Chiapas. This state has about 8000 species of vascular plants, whereas only about 440 species of fungi (Andrade-Gallegos & Sánchez-Vázquez, 2005) are known, out of the 20 000 estimated species (Chanona-Gómez, Andrade-Gallegos, Castellanos-Albores & Sánchez, 2007), representing only 2.2% of the estimated total. Recent research has found that most studies have been conducted in areas of the Lacandon Jungle, the Soconusco Coastal Plain, and Chiapas highlands in the municipalities of San Cristobal, Oxchuc, Zinacantan, and Chamula (Andrade-Gallegos & Sánchez-Vázquez, 2005). The San Jose (SJ) educational park is in the municipality of Zinacantan, Chiapas, with an altitude of 2350 MASL. Two species have been recently reported in this area, Agaricus silvaticus Schaeff and Auriscalpium vulgare (L.) Kuntze (Robles-Porras, Ishiki-Ishihara & Valenzuela, 2006). This study aims to create an inventory of the mycodiversity of San José educational park, in the municipality of Zinacantan, Chiapas.

Materials and Methods

Study area

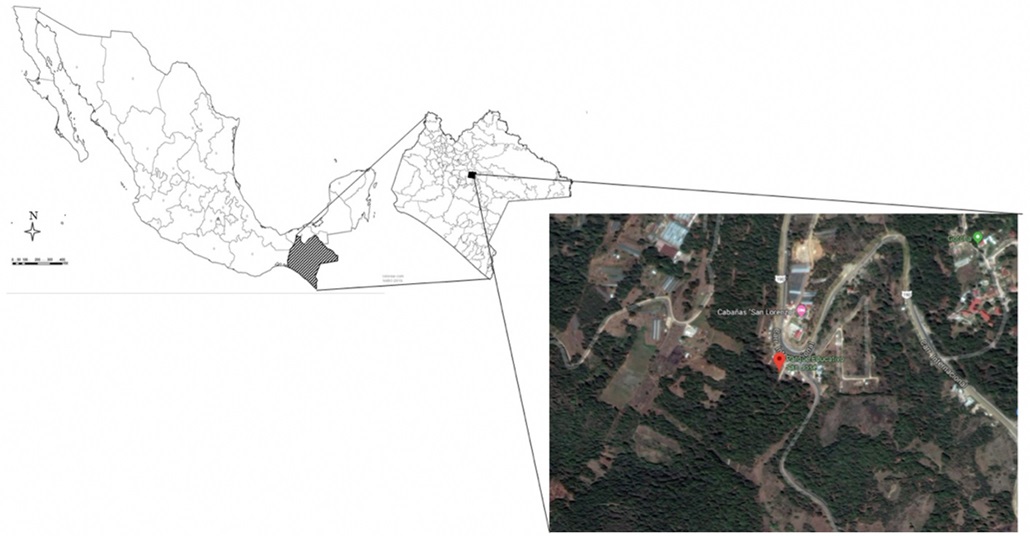

It was located at the San Jose educational park, which is bordered on the north by the foothills of the natural protected area Huitepec (Instituto de Historia Natural y Ecología[IHN], 2004) and is located at 9 km southwest of the city of San Cristobal de las Casas, Chiapas (Figure 1). Its predominant vegetation is the pine-oak forest and oak-pine, overhanging the following tree species: Pinus ayacahuite, P. strobus, P. teocote, P. montezumae, P. oocarpa, Quercus oleoides, Q. lancifolia and Q. chartacea (Álvarez-Espinoza, 2006). There is no permanent surface water on the site, and it is only temporarily crossed by the runoff of rainwater from the higher surrounding areas (IHN, 2004).

Sample collection and determination

The sample collection was performed on 12 mycological paths over the five years of the study, in order to explore and determine the macrofungal diversity of the studied area. Sampling was conducted through random walks crossing points throughout the area. This work consisted of listing the species collected in the SJ macromycetes park between the months of May and November, during the years 2009 to 2013. The collected specimens were identified according to their morphological characters with dichotomous keys and herborization. The macroscopic characteristics for determination were color, size, type of hymenium, presence/absence of volva, ring and other ornaments. The microscopic characteristics for determination were spore form and size. Data collection and data field recording were carried out according to Guzmán (1977) and screened for macromycetes growing on different substrates. Following the determination, the studied specimens were deposited in the Herbarium at the Institute of Natural History of the State of Chiapas. The identification was made using a macro and microscopic analysis based on the concept of morphospecies. In cuts for microscopic analysis of the fruiting body with spores, color changes were observed when adding 5% potassium hidroxide (KOH), methylene blue, and Congo red. Such determination was made using dichotomous keys and consulting specialized literature (Díaz-Barriga, 1992; Gilbertson, 1979; Gilbertson & Ryvarden, 1986; 1987; Guzman, 1977; 1979; Moser, 1978).

Results

A total of 380 specimens of macromycetes were collected at SJ park, and 148 species were determined (Figure 2); twenty-one (14.28%) of them belong to Ascomycotina (Table 1) and 126 (85.71%) to Basidiomycotina (Table 2). Of the total specimens, 71.42% were determined as species and the rest as genus, due to the lack of identification keys in the specialized literature. Twenty-seven new specimens were recorded for Chiapas (Table 3). Eighteen percent of the total new registrations correspond to Ascomycotina and 82% to Basidiomycotina. Seventy-eight new records for SJ park. The taxa with species more often found were Helvellaceae, with six species for Ascomycotina; while for Basidiomycotina, there were Amanitaceae (16 species, 10.88%), Tricholomataceae (15 species, 10.20%), Boletaceae (12 species, 8.16%) and Russulaceae (8 species, 5.4%).

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

Figure 2 Representative macrofungi found in PESJ. A. Boletellus betula Schewein; B. Clitocybe clavipes (Pers.:Fr) Kumm; C. Crucibulum laeve (Huds. Ex Relh) Kambly; D. Tremella foliacea Pers; E. Craterellus cornucopioides (L.) Pers; F. Gyromitra infula (Schaeff.) Quél; G. Geoglossum fallax E. J. Durand; H. Amanita vaginata (Bull.: Fr.) Vitt; I. Cortinarius violaceus (L.:Fr.) Gray; J. Amanita vittadini (Moretti) Vittadini.

Table 1 List of Ascomycetes (Division Ascomycota, Class Ascoycotina) of the San Jose Park, Zinacantan, Chiapas.

| Order | Family | Substrate | Importance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heliotiales | Leotiaceae | Leotia lubrica Fries SJ, Ch | H | M; E; ME |

| Leotia viscosa Fr. | H | M | ||

| Hypocreales | Cordycipitaceae | Cordyceps capitata (Hamski:Fr.) Link SJ, Ch | P | R |

| Pezizales | Geoglosaceae | Geoglossum fallax E. J. Durand SJ, Ch | H | NE |

| Helvellaceae | Helvella lacunosa ex Fries SJ | H | M; E | |

| Helvella sp. | H | M | ||

| Helvella crispa Scop.Fr. | H | M; E | ||

| Macropodia macropus (Pers.) Fuckel SJ | H | S; E | ||

| Paxina acetabulum (L. ex Amans) Kuntz SJ, Ch | H | S; E | ||

| Gyromitra ínfula (Schaeff.) Quél SJ | H | M; E | ||

| Humariaceae | Aleuria aurantia (Fr.) Fuck SJ, Ch | H | E | |

| Otideaceae | Otidea alutacea (Pers.) Massee | H | S; NE | |

| Otidea onotica (Pers.) Fuckel | H | S; NE | ||

| Scutellinia scutellata (L.) Lambs SJ | L | S | ||

| Pezizaceae | Peziza hemisphaerica Hoffm SJ, Ch | H | NE | |

| Peziza leucomelas (Pers.) Kuntze SJ, Ch | H | NE | ||

| Peziza sp. | H | NE | ||

| Sarcoscyphaceae | Sarcosphaera eximia (Durieu & Lév.) Maire SJ, Ch | L | S; D | |

| Sarcoscypha coccínea (Scop.:Fr.) Lamb SJ, Ch | H | NE | ||

| Xylariales | Xylariaceae | Hypoxylon thouarsianum (Lév.) Lloyd | L | S; NE |

| Xylaria hypoxylon (L.:Fr.) Grev | L | S; NE |

SJ New records for San José park

Ch New records for Chiapas

Substrate: H: humus; L: Lignicola;

Importance: S: Saprobe; M: Mycorrizic; P: Parasite; C: Edible; T: Toxic; NC: Non-edible; ME: Medicinal; R: Ritual; I: Insecticide; D: Dye; S: Special protection

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

Table 2 List of Basidiomycetes (Division Basidiomycota, Class Basidiomycotina) of San Jose Park, Zinacantan, Chiapas.

| Order | Family | Substrate | Importance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agaricales | Agaricaceae | Agaricus silvaticus Schaeff Fr. SJ | H | M; C |

| Chlorophyllum molybdites (G. Mey.: Fr.) Massee SJ | H | S; T | ||

| Leucocoprinus fragilissimus (Ravenel ex Berk M.A. Curtis) Pat SJ, Ch | H | NC | ||

| Macrolepiota procera (Scop.:Fr.): Singer SJ | H | C | ||

| Amanitaceae | Amanita caesarea (Scop.: Fr.) Grev SJ | H | M; C; SPE | |

| Amanita codinae (Maire) Bertault SJ, Ch | H | M; T | ||

| Amanita flavoconia G.K. Atk | H | M; T | ||

| Amanita fulva (Schaeff.) Fr. SJ | H | M; C | ||

| Amanita gemmata (Fr.) Bertill SJ | H | M; T | ||

| Amanita hemibapha (Berk & Broome) Sacc SJ, Ch | H | M; T | ||

| Amanita citrina (Schaeff) Pers. SJ, Ch | H | M; T | ||

| Amanita perpasta Corner & Bas SJ, Ch | H | M | ||

| Amanita muscaria (L.:Fr.) Lam | H | M; ME; I; T | ||

| Amanita rubescens (Pers. Ex Fr.) Gray | H | M; C | ||

| Amanita vaginata (Bull.: Fr.) Vitt | H | M; C | ||

| Amanita sp. 1 | H | M | ||

| Amanita sp. 2 | H | M | ||

| Amanita pantherina (Dc.:Fr.) Krembt SJ | H | M; T | ||

| Amanita virosa (Fr.) Bertault SJ | H | M; T; LRPV | ||

| Amanita vittadini (Moretti) Vittadini SJ, Ch | H | M; C: LRPV | ||

| Bolbitiaceae | Conocybe sp. | H | S | |

| Coprinaceae | Coprinus sp. | L | S | |

| Coprinus atramentarius (Bulliards.:Fries) Fries SJ, Ch | H | C; ME | ||

| Panaeolus semiovatus (Sow.:Fr.) Lundell & Nannf SJ | E | S; T | ||

| Psilocybe sp. | E | S; R; T | ||

| Cortinariaceae | Cortinarius sp. | H | S | |

| Cortinarius violaceus (L.:Fr.) Gray SJ | H | C; TI | ||

| Rozites caperatus SJ, Ch | H | S; C | ||

| Inocybe sp. 1 | H | M; T | ||

| Inocybe sp. 2 | H | M; T | ||

| Crepidotaceae | Crepidotus mollis (Schaeff.) Staude | L | S | |

| Hygrophoraceae | Hygrophorus sp. 1 | H | S | |

| Hygrophorus sp. 2 | H | S | ||

| Hygrophorus psittacinus (Schaeff.) Fr. SJ, Ch | H | S | ||

| Lepiotaceae | Lepiota sp. | H | S | |

| Mycenaceae | Mycena acicula (Schaeff.) Kummer SJ, Ch | H | S | |

| Mycena sp. | H | S | ||

| Strophariaceae | Pholiota squarrosa (Vahl.) P. Kumm SJ, Ch | L | S; T | |

| Hebeloma sp. SJ | H | S | ||

| Hypholoma fasciculare (Fr.) SJ, Ch | L | S; T | ||

| Naematoloma dispersum (Quél) P. Karst | H | S | ||

| Naematolomma sp. 1 | H | S | ||

| Tricholomataceae | Armillariella mellea (Vahl.) P. umm SJ | P | C | |

| Clitocybe clavipes (Pers.:Fr.) Kumm SJ, Ch | H | S; C | ||

| Clitocybe gibba (Pers.:Fr.) Kummer SJ | H | M; C; ME | ||

| Clitocybe sp. | H | S | ||

| Collybia alkalivirens Singer SJ, Ch | H | S | ||

| Tricholoma equestre (L.) P. Kumm SJ, Ch | H | S; T | ||

| Collybia dryophila (Bull.:Fr.) Murrill | H | C | ||

| Collybia sp. 1 | H | S | ||

| Collybia sp. 2 | H | S | ||

| Laccaria amethistina (Bolton: Hook.) Murrill | H | M; C | ||

| Laccaria laccata (Scop.:Fr.) Berk & Boome | H | M; C | ||

| Lentinellus sp. | H | S | ||

| Lyophyllum decastes (Fr.) Singer SJ, Ch | H | C | ||

| Marasmius sp. | H | NC | ||

| Omphalotus olearius (D.C.) SJ, Ch | P | T | ||

| Psathyrellaceae | Psathyrella sp. | H | S | |

| Pterulaceae | Ptreula sp. | H | S | |

| Phallaceae | Phallus impudicus L. | H | M; C | |

| Phallus ravenelii Berk & M. A. Curtis SJ, Ch | H | M | ||

| Schizophyllaceae | Schizophyllum commune Fr. SJ | L | S; C; ME | |

| Physalacriaceae | Oudemansiella canarii (Jungh.) Höhn SJ | L | S; C | |

| Auriculariales | Auriculariaceae | Auricularia auricula (Bull.:Fr) Wettit SJ | L | C; S |

| Boletales | Boletaceae | Austroboletus gracilis (Corner) Wolfe | H | M |

| Boletus griseus Frost SJ | H | M; LRPV | ||

| Boletellus betula Schwein SJ | H | M; C | ||

| Boletellus obscurococcineus (Höhn.) Singer SJ, Ch | H | M | ||

| Boletus sp. 1 | H | M | ||

| Boletus sp. 2 | H | M | ||

| Boletus sp. 3 | H | M | ||

| Boletus sp. 4 | H | M | ||

| Porphyrellus porphyrosporus (Fr.) Gilbert SJ, Ch | H | M; LRPV | ||

| Suillus tomentosus (Kauffman) Singer SJ, Ch | H | M | ||

| Suillus sp. | H | M | ||

| Xerocomus sp. | H | M | ||

| Hygrophoropsidaceae | Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca (Wulfen) Maire SJ, Ch | H | C; S | |

| Cantharellales | Cantharellaceae | Craterellus cornucopioides (L.) Pers. SJ, Ch | H | M; C |

| Craterellus lutescens (Fr.) Fr. SJ | H | M; C | ||

| Cantharellus cibarius Fr. SJ | H | M; C; SPE | ||

| Cantharellus tubaeformis Fr. | H | C | ||

| Clavariadelphaceae | Clavariadelphus pistillaris L. ex Fr. SJ, Ch | H | S; C | |

| Clavariaceae | Clavaria vermicularis Fries SJ | H | S | |

| Ramariopsis sp. | H | NC | ||

| Hydnaceae | Hydnum repandum (L.) Fr. | H | M; C; ME | |

| Sparassidaceae | Sparassis crispa (Wulfen) Fr. | L; P | S; C; ME | |

| Ganodermatales | Ganodermataceae | Ganoderma lucidum (Leyss ex Fr.) Karst SJ | L | S; ME; P |

| Gomphales | Ramariaceae | Ramaria sp. 1 | CP | S |

| Ramaria sp. 2 | L | S | ||

| Ramaria sp. 3 | H | S | ||

| Ramaria sp. 4 | H | S | ||

| Ramaria stricta (Pers.) Quél | H | M; C | ||

| Hericiales | Auriscalpiaceae | Auriscalpium villipes (Lloyd) Snell & EA Dick | CP | S |

| Auriscalpium vulgare Gray | L | S; NC | ||

| Clavicorona sp. | H | NC | ||

| Hymenochaetales | Hymenochaetaceae | Phellinus sp. | L | S |

| Lycoperdales | Geastraceae | Geastrum triplex Jungh SJ | H | M; ME |

| Lycoperdaceae | Lycoperdon perlatum SJ | H | M | |

| Bovista sp. | H | NC | ||

| Nidulariales | Nidulariaceae | Crucibulum laeve (Huds. Ex Relh) Kambly SJ, Ch | L | S; NC |

| Thelephorales | Thelephoraceae | Thelephora terrestris Ehrenb SJ, Ch | H | S; NC |

| Bankeraceae | Phellodon niger (Fr.) P. Karst | H | T | |

| Hydnellum peckii (Banker) Sacc SJ, Ch | H | M; LRPV | ||

| Poriales | Coriolaceae | Fomes sp. | L | S |

| Perenniporia piophilia SJ | L | S | ||

| Trametes versicolor (L.) Pil SJ | L | S; ME | ||

| Lentinaceae | Pleurotus djamor (Rumphius:Fr.) Boed | L | S; C | |

| Polyporaceae | Polyporus sp. 1 | L | S | |

| Polyporus sp. 2 | L | S | ||

| Polyporus sp. 3 | L | S | ||

| Meruliporia incrassata (Berk. & M.A. Curtis) Murrill SJ, Ch | L | S | ||

| Favolus brasiliensis (Fr.) Fr. SJ | L | S | ||

| Coltricia perennis (L:Fr.) Murr SJ | L | S; C | ||

| Meruliaceae | Steccherinum ochraceum (Persoon.:Fries) S.F. Gray SJ, Ch | L | S | |

| Russulales | Russulaceae | Lactarius deliciosus (Fries) S.F. Gray | H | M; C; ME |

| Russula mexicana Burl.SJ | H | M; T | ||

| Russula brevipes Peck | H | M; C | ||

| Russula cyanoxantha (Schaeff ex Schwein) Fr SJ | H | M; C | ||

| Russula heterophylla (Fr.:Fr.) Fr. SJ, Ch | H | M | ||

| Russula subfoetens W. G. Smith SJ | H | M; T | ||

| Russula sp. 1 | H | M | ||

| Russula sp. 2 | H | M | ||

| Sclerodermatales | Sclerodermataceae | Scleroderma areolatum Ehrenb SJ | H | M; ME; T |

| Stereales | Stereaceae | Stereum hirsutum (Willdenow: Fries) S.F. Gray SJ | L | S; NC |

| Tremellales | Exidiaceae | Exidia alba (Lloyd) Burt SJ, Ch | H | S |

| Tremella foliacea Pers. | L | S | ||

| Tremella mesenterica Retz SJ, Ch | L | S; NC |

SJ New records for San José park

Ch New records for Chiapas

Substrate: H: humus; L: Lignicola;

Importance: S: Saprobe; M: Mycorrizic; P: Parasite; C: Edible; T: Toxic; NC: Non-edible; ME: Medicinal; R: Ritual; I: Insecticide; D: Dye; S: Special protection

Source: Author’s own elaboration.

Table 3 New records of macromycetes for Chiapas San José park, Zinacantan, Chiapas.

| Order | Family | |

|---|---|---|

| Hypocreales | Cordycipitaceae | Cordyceps capitata (Hamski.:Fr.) Link |

| Pezizales | Helvellaceae | Paxina acetabulum (L. ex Amans) Kuntz |

| Humariaceae | Aleuria aurantia (Fr.) Fuck | |

| Sarcosphaera eximia (Durieu & Lév) Maire | ||

| Sarcoscyphaceae | Sarcoscypha coccínea (Scop.:Fr.) Lamb | |

| Agaricales | Amanitaceae | Amanita codinae (Maire) Bertault |

| Amanita hemibapha (Berk & Broome) Sacc | ||

| Amanita citrina (Schaeff) Pers | ||

| Amanita perpasta Corner & Bas | ||

| Coprinaceae | Coprinus atramentarius (Bulliards.:Fries) Fries | |

| Cortinariaceae | Rozites caperatus | |

| Hygrophoraceae | Hygrophorus psittacinus (Schaeff.) Fr. | |

| Strophariaceae | Pholiota squarrosa (Vahl.) P. Kumm | |

| Tricholomataceae | Clitocybe clavipes (Pers.:Fr) Kumm | |

| Collybia alkalivirens Singer | ||

| Lyophyllum decastes (Fr.) Singer | ||

| Omphalotus olearius (D.C.) | ||

| Phallaceae | Phallus ravenelii Berk & M. A. Curtis | |

| Boletales | Boletaceae | Boletellus obscurococcineus (Höhn.) Singer |

| Porphyrellus porphyrosporus (Fr.) Gilbert | ||

| Hygrophoropsidaceae | Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca (Wulfen) Maire | |

| Cantharellales | Cantharellaceae | Craterellus cornucopioides (L.) Pers. |

| Clavariadelphaceae | Clavariadelphus pistillaris L. ex Fr. | |

| Poriales | Meruliaceae | Steccherinum ochraceum (Persoon.:Fries) S.F. Gray |

| Russulales | Russulaceae | Russula heterophylla (Fr.:Fr.) Fr. |

| Tremellales | Exidiaceae | Exidia alba (Lloyd) Burt |

| Tremella mesenterica Retz |

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

Substrates

Macromycetes on humus (110 species) and on wood (32 species) were the most common. This is probably correlated with the type of vegetation, that is, pine-oak and oak-pine which constantly shed fascicles (pine needles) and broad leaves of Quercus, thereby, creating acid soil and high humidity which, along with the variety of microhabitat, produce the development of fungi on humus (Lodge & Cantrell, 1995). This is consistent with those reported by Guzmán-Dávalos & Guzmán (1979), who claim there are more lignicolous fungi in the tropics than in coniferous forests due to weather factors that promote the formation of humus.

Saprobes and ectomycorrhizal species

In addition, the results indicate that the group of saprobe fungi were the most common (68 species, 46.25%), followed by the ectomycorrhizal species (59 species, 40.13%). This is probably due to the fact that mycorrhizae develop in greater proportion in coniferous forests, compared to forests or rainforests, probably because weather conditions are generally not the most adequate; therefore, trees need to partner with other living organisms and other agents in order to properly absorb nutrients (Guzmán-Dávalos & Guzmán, 1979). Based on the results obtained, the families Amanitaceae (16 species, 10.88%), Tricholomataceae (15 species, 10.20%), and Boletaceae (12 species, 8.16%) were the most abundant within the group of mycorrhizae, which play a role in developing ecological forest populations and ecological succession, as well as in the promotion and alteration of the functions of niches (Kadowaki et al., 2018). According to the findings by Garza, García & Castillo (1985), the genus Amanita is closely linked to productivity and the maintenance of a healthy forest. Some ectomycorrhizae, like Amanita and Russula, can use vegetable cellulose and polymers for degradation by joining broadleaf trees such as oaks, hence the importance of the study area where some species of Quercus sp. are dominant (Deacon, 1993).

The most common genera of ectomycorrhizal fungi observed were Amanita, Boletus, Cantharellus, Clavariadelphus, Clitocybe, Gyromytra, Helvella, Inocybe, Laccaria, Lactarius, Ramaria, Russula, Scleroderma and Suillus; therefore, it can be concluded that these taxonomic groups are abundant in Quercus forests (López-Eustaquio, Portugal, Bautista & Venegas, 2010; Pérez-Silva, Esqueda, Herrera & Coronado, 2006). Guzmán-Dávalos & Guzmán (1979) and Landeros, Castillo, Guzmán & Cifuentes (2006) also found abundant ectomicorrizogen species in these type of forests.

Edible fungi

A total of 43 (31.29%) edible species were found: Agaricus silvaticus, Aleuria aurantia, Amanita vaginata, Amanita caesarea, Amanita fulva, Amanita rubescens, Amanita vittadini, Armillariella mellea, Auricularia auricula, Boletellus betula, Cantharellus cibarius, Cantharellus tubaeformis, Clavariadelphus pistillaris, Clitocybe clavipes, Clitocybe gibba, Collybia dryophilus, Coltricia perennis, Coprinus atramentarius, Cortinarius violaceus, Craterellus cornucopioides, Craterellus lutescens, Gyromitra infula, Helvella crispa, Helvella lacunose, Hydnum repandum, Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca, Laccaria amethystina, Laccaria laccata, Lactarius deliciosus, Leotia lubrica, Lyophyllum decastes, Macrolepiota procera, Macropodia macropus, Oudemansiella canarii, Paxina acetabulum, Phallus impudicus, Pleurotus djamor, Ramaria stricta, Rozites caperatus, Russula brevipes, Russula cyanoxantha, Schizophyllum commune and Sparassis crispa. These species might be a sustainable food alternative for residents near the SJ park, as they could be used sustainably with biotechnological processes through cultivation; therefore, they can be considered as non-timber forest resources to contribute to the forest conservation and form a fundamental part of the structure and operation thereof, aiding in the capture of water, the conservation of diversity and as a source of income through alternative tourism or ecotourism (Pilz, Norvell, Danell & Molina, 2003).

Toxic fungi

Twenty-two (14.96%) taxa of toxic and hallucinogen fungi were found: Amanita citrina, A. codinae, A. flavoconia, A. gemmata, A. hemibapha, A. muscaria, A. pantherina, A. virosa, Chlorophyllum molybdites, Hypholoma fasciculare, Inocybe sp. 1, Inocybe sp. 2, Omphalotus olearius, Panaeolus semiovatus, Phellodon niger, Pholiota squarrosa, Psilocybe sp., Russula mexicana, Russula subfoetens, Sarcosphaera eximia, Scleroderma areolatum and Tricholoma equestre. The most abundant genera were Amanita; some of them may cause mycetism due to their toxicity (Díaz-Barriga, Guevara, Ferer & Valenzuela, 1988; Garza et al., 1985). Chlorophyllum molybdites and Scleroderma areolatum produce gastrointestinal mycetism, characterized by headache, fatigue, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea (Ott, Guzmán, Romano & Díaz, 1975). Gyromitra esculenta, although it is considered edible in some regions of Mexico, can have a neurotoxic effect (Carod-Artal, 2005). Coprinus atramentarius causes Coprinic syndrome, or disulfiram reaction (Pérez-Silva et al., 2006), while some species of Amanita, Clitocybe y Omphalotus contain muscarin and, therefore, may cause muscarinic syndrome. Amanita muscaria is one of the most toxic species known in Mexico, and it is considered toxic, hallucinogenic, medicinal and is even used as an insecticide. Some species of Helvella and Gyromitra can be eaten boiled, and the boiling water should be discarded, because they are toxic when consumed raw. According to Madrid (2005), Schizophyllum commune causes sinusitis, bronchopulmonary fungal infections, meningitis and lesions of the palate, although in Chiapas it is considered an edible mushroom. Only two fungi species (hallucinogens) growing on dung were found (1.36%), indicating that despite the fact of the area having moderate or latent disturbances, the incidence of free wild animals and/or livestock within the park is low. The zoo cages were not sampled due to security reasons. These results agree with Heredia (1989) at the Reserva El Cielo; both are protected areas. The ratio toxic: edible fungi was 1:2.3, which means that edible mushrooms are more abundant than toxic fungi.

Fungi with biotechnological and medical applications

Inside the SJ park, some fungi were found to have biotechnological and medical applications. Cortinarius violaceus, according to local knowledge, is a fungus used for the extraction of dyes which produce a stained purple-violet color. The dye can be extracted with a 70% ethanol solution. In Mexico, and specifically in Chiapas, some species are considered to have medicinal properties, such as: Amanita muscaria, Clitocybe gibba, Coprinus atramentarius, Ganoderma lucidum, Geastrum triplex, Hydnum repandum, Lactarius deliciosus, Leotia lubrica, Schizophyllum commune, Scleroderma areolatum, Sparassis crispa and Trametes versicolor. According to Ceballos et al. (2009), in México, Amanita muscaria and Lactarius indigo are used as purgatives; Amanita caesarea is used as an anti-inflammatory, and Lactarius deliciosus is used for asthma and intestinal pains. According to the results of this study, the mycological value of SJ park is higher than that of the Parque Educativo Laguna Bélgica, another park in Chiapas (Chanona-Gómez et al., 2007).

Discussion

In this study, and in former ones by the authors (Chanona-Gómez et al., 2007), it was observed that in the pine forests the soil is thinner and has less organic matter incorporated, compared with oak forest. The mulch in the oak forest is thicker and deeper, less acidic, and it has high levels of phosphorus, potassium and magnesium. This contributes to different nutrients’ cycle of matter and energy, as well as to the diversity in ecotones, where both types of vegetation coexist. The amount of decomposed wood is lower than in other tropical zones; therefore, the species growing on wood tend to be less than those growing on humus. Deacon (1993) reports that some trees produce phenolic compounds that inhibit the growth of some species which are probably found in diverse proportion and abundance; so, the species that grow on decaying wood are highly specialized. The most abundant fungi that had grown on organic matter belong to the Polyporaceae family, while the Amanitaceae family was predominant for humus growing fungi (16 species, 10.88%).

Meanwhile, the saprobes and mycorrhizae fungi are important organisms for the ecological balance of the forest, because they decompose organic matter and degrade cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin in ecosystems, and contribute to form the humus and the process of remineralization of the soil (Zamora-Martínez, 1999). However, saprobe fungi can cause economic loses for rational forest exploitation, because they reduce production levels and wood quality (López-Eustaquio et al., 2010).

The results of the macrofungal diversity obtained may be due to the types of vegetation in the area, coverage, and/or tree density, successional forest condition, relative humidity, texture and soil compaction (due to humans and animals) as well as chemical composition and abundance of existing litter on the forest floor, which can be strongly influenced by environmental pollutants (Villanueva-Jiménez, Villegas-Ríos, Cifuentes-Blanco & León-Avedaño, 2006). According to Rydin, Diekmann & Hallingbäck (1997), the alteration of forest systems is based on the relation of the percentage of micorrizogenic species relative to the percentage of the total macromycetes. Based on this, it can be said that SJ park has an alteration or transformation known as latent type, because the percentage of the mycorrhizal fungi is higher than 40% and the lignicolous is less than 30%. This can be confirmed by observing the surrounding forest where the number of pedestrians, cars, buildings, crops and houses is growing by the day, which indicates a latent anthropogenic pressure and possible alteration of the environment.

Álvarez-Espinosa (2006) reported 80 species of macromycetes for SJ park, while the present research reports 148 species, 54.42% higher than those found in previous years. This may be due to several factors, such as seasonality of phenology and fructification of various species, relative humidity caused by the amount of rain and dew, effort (time and amount) of collection, which result in a significant loss of species identified and analyzed (Gazis, 2007; Lodge, 1997). Consequently, the results show fungal families that were never reported for SJ park before, such as Cortinariaceae and Hygrophoraceae, and new records for Chiapas and for the area. Thus, this study contributes significantly to the knowledge of the microbiota of SJ park and Chiapas.

According to Lodge (2001), Agaricales and Polyporales can adapt to changing conditions of temperature, humidity and rainfall through diverse dispersal strategies adapted to rain and wind, while Coprinus, Hydnum, Lycoperdon and Marasmius are primary colonizers in the process of succession, indicating that they are better suited to environments with moderate disturbance (Ortíz-Moreno, 2010). Also, the SJ park has successional linked to developmental processes, so that the mycorrhizal community can vary with the age of the trees and, therefore, the age of the forest. Both mycorrhizal fungal communities and saprobe fungi also exist in successional stages (Martínez-Peña 2008), so the number of species might increase the new collections made in the study site.

The study area is 15 ha, approximately, which corresponds to the 0.0198% of the Chiapas area, and this study has reported a total of 148 species, meaning a high fungal richness. Based on these results, and according to the Hawskorth index, it can be used to extrapolate the fungal diversity for the SJ park, so it is expected that area could have about 800 species of fungi, which means that it is still possible to find a greater number of species at the area. Thus, it is important to make new collections for longer periods, because the phenology of species is very variable. A greater effort of sampling, and a superior taxonomic study for identification are recommended. Currently, the area is protected by the Instituto de Historia Natural del Estado de Chiapas (Institute of Natural History of the State of Chiapas), and some studies have been conducted in Chiapas, like Álvarez-Gutiérrez, Chanona-Gómez & Pérez-Luna (2014), but the number of taxonomic and ecological studies is limited.

Most of the SJ park specimens studied are species that have been described in forests of pine, oak and conifers of Mexico (Pardavé-Díaz, Flores-Pardavé, Ruíz-Esparza & Castañeda-Romo, 2012). For example, Schizophyllum commune is very common in tropical areas (Guzmán, 1979), and it is used as an indicator of disturbance (Díaz-Barriga et al., 1988), because it grows in sunny areas. Other common species of tropical zones were found, such as Favolus brasiliensis, Ganoderma aplannatum, G. lucidum, which usually develop in low densities in the forests of pine-oak forest transition to tropical rainforest (Guzmán-Dávalos & Guzmán, 1979). Chlorophyllum molybdites is a typical kind in paddocks of disturbed human areas and it was found near the limits of the park, which indicates that it is a latent disturbance area (Guzmán-Dávalos & Guzmán, 1979).

Studies conducted by López-Eustaquio et al. (2010), Guzmán (1979) and Guzmán-Dávalos & Guzmán (1979) reported that the characteristic species of pine-oak forests are Amanita caesarea, A. muscaria, A. vaginata, Clitocybe claviceps, Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca, Laccaria laccata, Lactarius indigo, Lyophyllum decastes, Macropodia macropus, Naematoloma fasciculare, Suillus tomentossus and Omphalotus olearius, which were found in SJ park. Also, Agaricus silvicola, Clitocybe gibba, Laccaria laccata, Lactarius deliciosus, Porphyrellus porphyrosporus, Russula brevipes and Xeromphalina campanella can be observed in pine-oak and fir forests.

A few species, such as Amanita caesarea, A. hemibapha, A. muscaria and Cantharellus cibarius are included in the category of vulnerable, according to the Official Mexican Standard NOM-059-ECOL-2001 (Diario Oficial de la Federación[DOF], 2002), while Amanita virosa, Amanita vittadini, Boletus griseus, Hydnellum peckii and Porphyrellus porphyrosporus are registered in the red list of the País Vasco (España) (Sociedad Pública de Gestión Ambiental, 2011).

Conclusion

Highlander regions of Chiapas have a wide biodiversity of macromycetes, in particular, conserved areas such as San José park at the municipality of Zinacantan, which according to the results of this study, the area has a wide micodiversity, with 148 species of macromycetes, 27 of them are new records for Chiapas.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)