Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Comunicación y sociedad

Print version ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc vol.20 Guadalajara 2023 Epub Mar 11, 2024

https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2023.8559

Articles

General theme

What Do Chilean Organizations Mean When They Claim to be Transparent?1

2Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile. pbravom@uc.cl

In Chile, transparency has become a prevalent topic in social and organizational discussions during a period of diminished institutional trust. This article identifies the meaning it carries for Chilean organizations through semi-structured interviews with 11 directors from public and private organizations. There are concentrated efforts to instrumentalize the concept from a legal perspective, as reflected in their communication strategies. However, this study suggests adding the relational dimension to contribute to the conceptualization of transparency from a communicational standpoint.

Keywords: Communication; transparency; organizations; Chile; relational perspective

El concepto de transparencia se instaló en el discurso social y organizacional en Chile en un contexto de bajos niveles de confianza institucional. El artículo identifica el significado que este tiene para las organizaciones chilenas, mediante entrevistas semiestructuradas a 11 directores de organizaciones públicas y privadas. Hay una concentración de esfuerzos por instrumentalizar el concepto desde lo legal, lo que se plasma en las estrategias comunicacionales. Sin embargo, este estudio plantea la dimensión relacional como aporte a su conceptualización desde la perspectiva comunicacional.

Palabras clave: Comunicación; transparencia; organizaciones; Chile; perspectiva relacional

O conceito de transparência foi instalado no discurso social e organizacional no Chile num contexto de baixos níveis de confiança institucional. O artigo identifica o significado que isto tem para as organizações chilenas, através de entrevistas semiestruturadas com 11 diretores de organizações públicas e privadas. Há uma concentração de esforços para instrumentalizar o conceito do ponto de vista jurídico, o que se reflete nas estratégias de comunicação. Contudo, este estudo levanta a dimensão relacional como contribuição para a sua conceituação na perspectiva da comunicação.

Palavras-chave: Comunicação; transparência; organizações; Chile; perspectiva relacional

Introduction

This article addresses the growing interest that the concept of transparency has sparked in Chilean organizations over the past two decades. It advocates expanding its comprehension beyond the present reductionist viewpoint, which is solely linked to complying with current regulations, towards a relational perspective, where organizational communication has a critical role. It is argued that, in Chile, institutions approach this construct with a functional objective, resulting in unidirectional communication strategies that reflect an unrestricted compliance to current regulations in the field. This sometimes leads to silencing what is relevant to citizens. There is a clear emphasis on the legal dimension of transparency, which prompts the instrumentalization of the construct through communication to demonstrate regulatory compliance and attain legitimacy, at the expense of directing its management based on the intrinsic value of the concept.

In light of the above, this article explores organizational understanding of transparency and what are the predominant dimensions of its conceptualization. The objective is to contribute from a Latin American case study to increase the understanding of the construct beyond the regulatory sphere, which by itself is not responding to citizens’ needs for transparency. Additionally, the aim is to highlight its close relationship with organizational communication from a relational perspective. Notably, the phenomenon of transparency in the field of communications has not been thoroughly studied (Wehmeier & Raaz, 2012), especially in Latin America (Cucciniello et al., 2016).

The article discusses two main topics: first, it explores the complicated nature of the concept, which has prevented experts from agreeing on a standard definition; second, it addresses the paradox that Chile has faced in terms of transparency. Despite making great progress in this area, the country still struggles with this issue facing growing citizen demands for greater institutional transparency. This is followed by a presentation of the methodology used and the results obtained. One of the notable findings is that the relational perspective is an articulator of communication and transparency management in organizations. Finally, the conclusion and limitations of the study are presented.

Transparency: a multidimensional and complex construct

The concept of transparency has now become firmly established in the global sociopolitical discourse (Albu & Flyverbom, 2016) and has acquired an unprecedented importance in the legitimacy of all types of organizations (Lehr-Lehnardt, 2005). It plays a central role in strengthening democracy and advancing countries’ progress towards development (Christensen & Cornelissen, 2015). Moreover, it has been the subject of growing academic interest since the beginning of the new century (Bauhr & Grimes, 2013; Cucciniello et al., 2016; Meijer, 2013; Schnackenberg & Tomlinson, 2016), as globalization, digitization, and economic integration have intensified social concern for higher levels of transparency (Baraibar-Diez et al., 2016). Nevertheless, there is a remarkable gap in the study of the phenomenon in Latin America (Cucciniello et al., 2016), particularly in the realm of communications (Wehmeier & Raaz, 2012).

The concept of transparency is intricate, multidimensional, interdisciplinary, and traces its historical roots back several centuries (Hood & Heald, 2006). Furthermore, there is no academic consensus on a singular definition or theoretical proposals that allow for an indepth understanding of it and that combine the various disciplinary perspectives of which it is the object of study (Florini, 2000; Lee & Boynton, 2017; Parris et al., 2016; Plaisance, 2007; Schnackenberg & Tomlinson, 2016).

Notably, the concept of transparency has evolved over time, adapting to societal changes that have revealed institutional crises linked to varying degrees with perceived serious lack of transparency, particularly in the last 20 years. Thus, the construct has become a widespread aspiration of society regarding the behavior of its organizations. This desire for a more transparent society reflects a wide range of social expectations (Baume & Papadoupoulus, 2018), as it is associated with various qualities and carries a strong moral component.

The historical analysis of transparency highlights five distinct dimensions of the concept. The first refers to the political dimension that emerged in the discourse of the late 18th century, when it was considered a moral, legal, and political project that manifested itself “against the ‘opacity’ of arbitrary acts” (Baume & Papadopoulos, 2018, p. 170). This led to social activism in pursuit of greater transparency, establishing it as a public value. This, in turn, resulted in the emergence of a moral dimension that relates to good governance practices3 (Berliner, 2014), among which ethical listening (Macnamara, 2016) plays a significant role.

Subsequently, administrative regulations were created, which gradually built their legal foundations. In line with this, Hood and Heald (2006) argued that certain ideas, approaches, and conceptualizations were shaping the current concept of transparency towards the 20th century. The authors observed the importance of the legal dimension in establishing a law-governed administration and avoiding discretionary practices, while emphasizing the necessity of transparent and honest communication, underscoring the intimate connection between transparency and communication. A fourth dimension is the technological aspect, emerging with the development of the Internet, which enables easier access to information and data storage. Similarly, the emergence of various media formats and digital platforms also contributed significantly to the expansion of the construct (Hallsby, 2020).

Finally, there is the presence of the societal dimension of transparency, closely related to concepts of openness (Ball, 2009; Edwards, 2020; Parris et al., 2016; Schauer, 2014), meaning that companies and governments maintain a policy of being open and tolerant; legitimacy, which refers to institutions operation within defined boundaries (Shocker & Sethi, 1973); and social accountability as an alternative control mechanism for governmental action through various initiatives set up by civil society and the media (Peruzzotti & Smulovitz, 2002).

In the context of the social dimension where the organization remains inserted, the relational dimension of communications becomes relevant. It is discussed in academic literature as a continuous interaction between organizations and their environments, with the goal of achieving balance to foster understanding and mutual benefit among all parties involved (Grunig & Hunt, 1984; Sadi & Mendez, 2015). Therefore, communication from this perspective either enables or prevents the phenomenon of transparency from materializing. In other words, transparency is not possible without communication (Camacho, 2016), which illustrates a close relationship where the presence of an interlocutor is essential, as it is this person who validates the information subject to transparency through the construction of meaning (Rodriguez & Opazo, 2007).

Chile: Facing citizen’s yearning for greater transparency

In Chile, transparency has also permeated the discourse of all types of organizations, especially as trust in institutions has declined systematically in recent years. This erosion of trust has undermined institutional credibility (Centro de Estudios Publicos [CEP], 2022). A series of cases show that the lack of transparency impacts both the public4 and private5 sectors, which has led to several crises with major repercussions for the country that even contributed to the social protests of October 2019 (Morales Quiroga, 2020). This article is framed in an unprecedented moment, not only for the country, for the reasons mentioned above, but also for Latin America in terms of its democratic development, where the transparency construct becomes relevant for citizens as an enabler and builder of institutional legitimacy (Berg & Feldner, 2017).

Chile is a country that has experienced undeniable progress in this area over the last three decades, as it has developed a robust legal and institutional framework for probity and transparency in accordance with international standards (Ministerio Secretaría General de la Presidencia, 2021). In 2008, the country enacted the Transparency of the Civil Service and Access to Information of the State Administration Law (Law 20.285). In this regard, it should be noted that a fundamental aspect for the proper implementation of regulatory frameworks lies in the establishment of a guarantor body whose function is to supervise both compliance with the legislation and the resolution of disputes in the disclosure and delivery of information. This task falls to the Consejo para la Transparencia (Council for Transparency), an institution established by law. It is an autonomous public corporation with legal personality and its own assets. It has received international recognition (Consejo para la Transparencia [CPLT], 2021) and has contributed to the institutional strength of Chile (Ministerio Secretaría General de la Presidencia, 2021).

However, the social context that has challenged the country in recent years has empowered citizens, who demand greater transparency and are skeptical of the institutional discourse (Consejo para la Transparencia, 2019). However, there is a discrepancy between institutional efforts toward transparency and the public’s perception of organizational transparency in Chile as they strongly report against institutional abuses (Consejo para la Transparencia, 2019). The crises of the last 20 years show that transparency approached solely from a legal dimension often fails to meet citizens’ needs (Tabuyo et al., 2019).

Conversely, the private sector exhibits a strong level of awareness regarding transparency. While private companies are not subject to this regulatory framework, they are still subject to regulations regarding the right of access to information, which are permanently supervised by the respective State institutions. As criminal liability of legal entities6 has been integrated into the legal system, the private sector has begun to incorporate compliance programs and crime prevention systems. In addition, many companies seek to comply with international self-regulation7 standards in order to have objective indicators of compliance with these requirements and thus provide assurance to their respective stakeholders of the highest level of corporate commitment to transparency. All of the above translates into systematic communication practices that seek a discourse of alignment embodied in a series of institutional reports (Hossain, 2017) to account for progress in the matter.

The combination of these three elements has contributed to the perception that organizations are highly vulnerable to the environment that surrounds them. Thus, the challenges of transparency are approached with fear and suspicion, which implies a cautious performance in the face of a phenomenon that demands more attention every day. In this context, the legal dimension of the construct is presented as a protective shield in the face of such adversity, helping to silence information that could make these organizations more vulnerable. In light of this, it is essential to advance in the understanding of the complexity of the phenomenon and how it is articulated with organizational communication. This will enable us to address transparency in a holistic manner and thus contribute to the regulatory frameworks.

Methodology

In order to determine the predominant dimensions in transparency conceptualization in Chilean organizations, a qualitative study with an intersubjective approach was conducted. This approach posits that knowledge is not merely the product of our individual minds, but rather that meaning and comprehension form a continuum of intelligibility (Given, 2008).

The study is based on semi-structured interviews with 11 directors of three organizations that were chosen on the basis of non-random sample criteria, since this technique is used in cases where the information is particularly relevant to answer specific questions (Teddlie & Yu, 2007). In line with the Huberman and Miles (1994) approach, organizations were selected that fulfilled one of three different reputational characteristics: exceptional organizations that had emerged stronger following a crisis, discrepant organizations that failed to recover from a devastating crisis, and organizations with a neutral nature. Based on these criteria, two organizations from the private sector and one from the public sector were selected.

It should be noted that the selection of organizations from both sectors is based on the search for common patterns, given that they are in different positions due to the Transparency Law and it is not the objective of this article to differentiate between them. The informants were defined according to criteria of adequacy and relevance (Sandoval, 1996), mainly considering two aspects; their position in the top management of the organization and their continuous interaction with the environment within their area of responsibility.

The 11 interviews were conducted and questions were developed according to Yin’s (2018) case study protocol. The recruitment strategy was based on an initial contact via e-mail, explaining the scope of the project and its absolute confidentiality. The interviews were recorded with the consent of the interviewees. Subsequently, a first transcription was made using the Amberscript software and then reviewed and corrected with the original audio.

The interviews were held between August 1st, 2021 and January 30th, 2022, with an average duration of 43 minutes. Due to the restrictions in force during the pandemic, the interviewees were given the possibility to conduct the interview remotely. As a result, nine of the 11 interviews were conducted online and two were conducted in person at the participants’ respective offices.

The analysis utilized descriptive, interpretative, and inferential coding (Huberman & Miles, 1994) to respond to the research questions. The iterative coding process developed allowed the construction of a conceptual map that identified four dimensions of transparency.

Results. Predominant dimensions in the conceptualization of transparency

There are four predominant perspectives in the interviewees’ conceptualization of transparency: legal, which alludes to compliance with current regulations and plays an instrumental role; moralethical, which considers transparency as an indisputable value; relational, referring to the capacity to connect with the various actors in society, and societal, which reflects the close dependence of organizations on their environment.

Legal Dimension: Transparency as a Synonym for Compliance with the Law and Information Control

The legal dimension emerges ipso facto when discussing transparency with the interviewees, and two main characteristics of this dimension are observed: the homologation of transparency with regulatory compliance and with information control. The first characteristic can be seen in the repeated mention of objective aspects (standards and laws) that are applied based on certain information and are manifested through processes that often involve the establishment of management indicators. The organizations allude to matters that make up the transparency law, which regulates the public sector, but there is also a discursive emphasis in both sectors (public and private) that transparency is synonymous with compliance with the legal framework in force, also alluding to other regulations that contain matters of access to information and probity issues.

The second characteristic of information control pertains to the legal dimension, which determines the status of public information that can be made transparent, while also facilitating alignment in communications and controlling perceived vulnerabilities in the face of threats. The control of information is the result of a clear interest in making the phenomenon of transparency tangible and showing society a growing evolution in this area by the organization in objective and unobjectionable terms.

The following are two quotes that illustrate this: “... I believe that ... it is transparent to disclose public information, but it is also transparent to say that this information is private and I am not going to disclose it” (01-04-13).8 This quote reflects a reductionist approach to the concept of transparency, since it is understood that only the disclosure of regulated subject matter is necessary to achieve transparency. It is understood that public information is that which is regulated and, therefore, the interviewee relies on the law to define what is disclosed. Furthermore, it is emphasized that the non-disclosure of information that is not public (information which is not regulated) is equally transparent. This reinforces that transparency, when solely viewed through a legal lens, represents a one-dimensional approach to the phenomenon, as it does not allow for a discussion regarding whether there are other factors that may influence the need to disclose particular information.

The following is the other interesting quote that exemplifies the way in which organizations use the regulatory framework to protect themselves from the adversity of the environment by controlling information: “Traditionally, one of the internal breaking points in any business organization is the legal management, because the legal management says it’s better not to disclose any information because any information can be used against you” (02-01-14). This quote captures a defensive attitude on the part of the interviewee, afraid of the consequences of providing certain information. Once again, transparency is conceived here as a rigid construct where only what is mandated by law should be disclosed, and anything else implies an unnecessary risk. Therefore, there is no room for interactive, two-way communication that would facilitate agreements between the parties involved.

Moral-Ethical Dimension: Transparency as an Undefinable Value

All the interviewees agree that the concept of transparency is an unquestionable or intrinsic value for the organization that allows them to guide their actions in an impeccable manner. However, this conceptualization is somewhat confusing when trying to explain how this value dimension is constructed for the organization. Transparency is related to “what is right, what ought to be”; however, its definition does not translate into practice beyond associating it with codes of ethics or good behavior. The following is an example of this:

By transparency, what I understand is that … I relate it to ethics … to comply not only with what is regulated by law, but it is a step beyond. It means being comfortable with the steps we take and how they align with the values the organization aims to convey. I believe that a fundamental part of every organization is its culture. I think that’s what makes them what they are, that they achieve their purpose … From my point of view, transparency comes with integrity. I believe that transparency transforms you into a trustworthy person and company (02-04-01).

In this quote, the interviewee associates transparency with a value that guides his actions beyond what is regulated. However, there is a lack of clarity and some difficulty in attempting to define transparency. It is first associated with compliance and then he digresses into concepts such as values, purpose, and integrity, finally concluding that transparency has a transformative effect. In other words, the organization regards it as a crucial value, without having much clarity as to how to define it or articulate it.

Relational Dimension: From Relational Conceptualization to Unidirectional Communication

All organizations frequently emphasize the importance of building networks with the various stakeholders that surround them. This is understood as the need to identify the key stakeholders with whom each organization is linked and its duty to interact with them. Such interaction should be proactive, collaborative and feedback should be integrated into their management, and some interviewees mentioned that it should be mediated by active listening. It should be noted that the discourse on this dimension is quite similar in all the organizations interviewed and shows conviction. Therefore, the conceptualization of the construct is based on the communicational logic of a relational and collaborative order.

However, when asked how much these organizations know about the management issues that matter to their stakeholders, the answers are vague and nonspecific. Organizations limit the process of getting to know their stakeholders to specific interactions established and related to certain areas of the organization and as reactive, segmented, and informative processes, where they are given information defined unilaterally by the organization. This dynamic is far from the dialogic nature and connection with the environment expressed by the interviewees. This is illustrated in the following quote:

How do I identify what my audiences are interested in? … Each area of the company has a target audience … and you have to know their interests and needs. When you know that, you know what you have to inform them. It is also what is managed, it’s not like everything for everyone and that’s it, I mean, there are some who are not interested in certain things … So, there is communication management in which each area has to manage its information to its audience. And there is a large audience, which is society, opinion leaders, and that’s more mediatic (01-03-05).

This quote reflects how the organization works to keep its stakeholder network unilaterally informed. The objective is to determine which predefined information is to be delivered to each stakeholder based on their specific needs, deviating from the collaborative approach originally proposed by the organization. There is no intention to offer responses on undefined topics but rather to engage in instrumental communication.

Societal Dimension: Transparency as a Link to Sustainability

The organizations report that there is a close relationship between them and their environment, in the sense that there are conditions beyond their control that affect their actions and may even threaten their sustainability. The organizations argue that today’s world requires institutions to move towards a social role, which is demanded by the context in which they are inserted. Thus, they conceive transparency in an organizationenvironment relationship, in the duty of organizations to be accountable to society (accountability), and thus achieve sustainability. However, it is observed that this conceptualization is mostly implemented at a basic level in terms of accountability, as it almost exclusively adheres to the guidelines stipulated by law or translates into very practical aspects. This is illustrated in the following quotes:

Transparency is transversal to the organization. We always say: “You have to be transparent” ... if you look at our mission, we have it mapped out and transparency is a fundamental part of our sustainability program that crosses the entire organization. For example, ... to make everyone feel more involved, you go to an aisle manager in one of our stores, and if he doesn’t tell you how much a certain department sells, it’s because he obviously can’t tell you, but he knows, and that’s information that other industries don’t share. You know what I mean? And it’s because we really believe that, in order to do management, you have to manage information. And transparency is a central axis in being able to summon these wills. Transparency is essential because without it the will of the stakeholders, in the broadest sense, is not summoned, and the organization ceases to exist (02-03-09).

In this context, the interviewee states his conviction regarding the value of transparency in fostering long-term relationships with stakeholders. He also underlines its undeniable value in the organization-environment relationship, as without it, the organization loses legitimacy, a key element for its sustainability.

This is another quote that illustrates what was stated above:

Our sustainability report adheres to the Global Reporting Initiative methodology, the gri, which is based in Holland. There they grade you on your level of transparency, to what extent are you providing certain information, and we have always from day one gone from less to more. Before, … we only reported the income statement and the annual report with financial data and little by little we started to add to this sustainability report, increasing this information following the guidelines that they are giving us (02-03-02).

This text shows how the organization defines the information that is subject to transparency in accordance with international guidelines, adjusting its accountability accordingly. The intention of a definition based on an interaction with the stakeholders is not observed.

Transparency and Communication from a Relational Perspective

The relational perspective of communications, as proposed in the literature, argues that the organization, in its ongoing interaction with the environment, must establish points of equilibrium to achieve understanding and mutual benefit for the parties involved in this interaction (Grunig, 1984; Sadi & Méndez, 2015). However, the interrelationship between communication and transparency at the organizational level in Chile could not be defined as relational. Two quotes illustrate this:

Transparency also means communicating the company’s strategy; conveying what we strive for as a company, communicating with passion and conviction … in other words, explaining why we want to do it, how we intend to do it, so there’s a sense of belonging and a greater involvement from our people … for them to understand why they are doing things and not just following instructions without understanding the purpose, and ultimately, so they feel a part of it. So … for me, transparency encompasses many areas. It includes the legal aspect, anticipating what they may scrutinize, being proactively transparent. But at the same time, it requires a special form of close, dedicated, demanding, yet also collaborative communication, so that everyone understands each other in this transatlantic ship, in the vessel we’re on, navigating through the sometimes very turbulent, sometimes very placid ocean (02-03-01).

The thing is, communication makes you more transparent, right? Now, how transparent do you want to be? Well, there is a strategic issue behind it because there are confidential issues... (03-03-11).

The first quote conveys a close relationship between transparency and communication since one is defined as a function of the other. Transparency is understood in its interrelation with a communication of very precise characteristics, but does not necessarily imply an integration of the receiver’s opinion in the decisions. It serves more as a strategic form of communication aimed at integrating internal stakeholders. The same happens with the second quote, where the allusion to the strategic role of communication is more evident.

Discussion and conclusions

Discrepancy Between the Dimensions of Transparency Prevalent in Chilean Organizations and those Suggested by the Literature

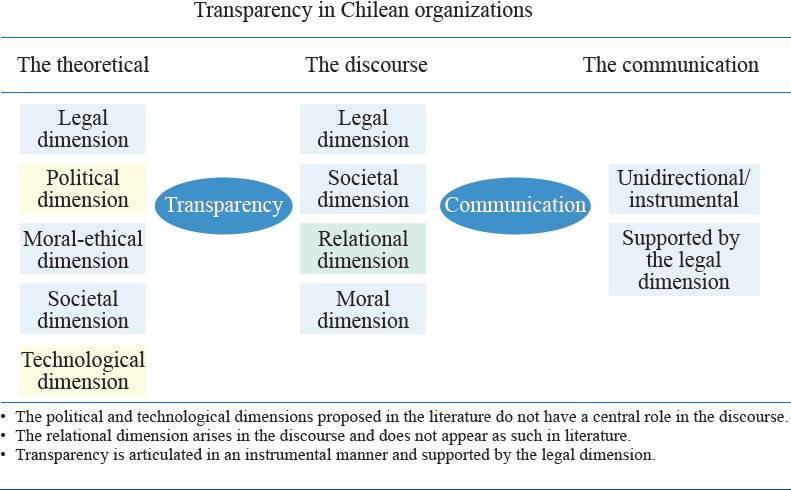

It is observed that organizations in Chile conceptualize transparency differently from the literature. Figure 1 shows that both the literature and the organizations agree on the existence of three dimensions: a strong legal dimension, a moral-ethical dimension, and a societal dimension. However, there are two dimensions in the literature that play an important role in the conceptualization of transparency and that appear with less emphasis in the discourse of the interviewees. These are the political and technological dimensions. On the other hand, in the discourse of the interviewees, a fourth dimension -the relational dimension- is quite prominent. While the literature does not explicitly state it as such, even though it could fall under the societal dimension due to the concepts of collaboration and participation associated with it, we find it relevant to propose it as an independent dimension, given the importance attributed to it by the interviewees.

The Relational Dimension of Transparency: A Contribution to its Conceptualization

The interviewees consistently assign a significant role to what is referred to in this study as the relational dimension. By this, we mean the need to identify key stakeholders with whom each organization is connected, and their duty to interact with them collaboratively, integrating their feedback into their management. This conceptualization highlights the important role of the information recipient in verifying if the transparent information meets their expectations, emphasizing the interdependence of transparency and communication from a relational point of view. Therefore, this dimension presents itself as an opportunity to broaden the view of the concept of transparency and thus approach it in a more comprehensive manner, incorporating the perspective of those who demand transparency.

Relational Dimension of Transparency in Response to Contextual Pressures

Based on Baume and Papadoupoulus’ (2018) statement about the construct of transparency reflecting various social expectations and evolving to adapt to societal changes, it is possible to argue that the relational dimension of transparency emerges in this process of adapting to citizens’ demands for greater transparency. This serves as a means to better respond to expectations in this matter, as the response given today is solely through the pathway determined by the legal dimension.

Instrumentalization of the Legal Dimension by Means of Unidirectional Communication

The legal dimension unquestionably takes precedence over the other dimensions. The focus is entirely on adhering to what is regulated, even if it may sometimes entail suppressing other issues that could be important to the public. This is evident in the tensions between the dimensions, especially when two values are in opposition, forcing the organization to decide which one to prioritize. Hence, the clash between the legal dimension and the moral-ethical or societal dimension of the construct is observed.

It should be noted that the fact that all organizations emphasize their unrestricted compliance to current regulations is not in question. However, it is relevant to note the tension that arises in the face of a regulatory framework that, in some way, provides room for the organization to take refuge in it and withhold other information (or to be less transparent) than what might be necessary. In these cases, confidentiality could be preferred based on this regulatory framework, as the legal dimension often prevails, to the detriment of what is required. In essence, utilizing the legal dimension in communication can serve as a means of shielding information from disclosure rather than revealing it.9

Challenges for Future Research

This study identifies the existence of four significant dimensions in the conceptualization of transparency for organizations in Chile. The legal dimension is argued to have more dominance over the other dimensions, demonstrating a reductionist approach to the construct and its utilization for organizational purposes. This perception of vulnerability experienced by organizations is partially due to increased demands for transparency from citizens. This understanding of a threatening environment may result in the suppression of issues that are indeed of public interest, prioritizing the disclosure of information solely bound by regulatory frameworks and strengthening one-way communication.

The conceptualization of the relational dimension of transparency is emphasized by organizations, which underscores the interaction between the organization and its network of stakeholders. It’s worth noting that this dimension is not explicitly stated in the literature, which is a valuable addition to the conceptualization of the construct, as it opens up the view towards incorporating other relevant dimensions for those who demand transparency.

The present paper raises some challenges to be covered by future research. This study is limited to analyzing three cases of organizations in Chile. Therefore, it would be interesting to expand this coverage and gain insight into how the construct is conceptualized in other countries at a regional level. It would be particularly valuable to understand the role that the relational dimension plays in them, as well as its impact on the communication of these organizations. Similarly, it would be useful to investigate potential differences on how the relational dimension of transparency operates in both the public and private sectors, a matter that was not addressed in this study.

REFERENCES

Albu, O. B. & Flyverbom, M. (2016). Organizational Transparency: Conceptualizations, Conditions, and Consequences. Business & Society, 58(2), 268-297. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650316659851 [ Links ]

Ball, C. (2009). What Is Transparency? Public Integrity, 11, 293-308. https://doi.org/10.2753/PIN1099-9922110400 [ Links ]

Baraibar-Diez, E., Odriozola, M. & Fernández Sánchez, J. L. (2016). Business Strategy and the Environment, 26(4), 480-489. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1931 [ Links ]

Bauhr, M. & Grimes, M. (2013). Indignation or Resignation: The Implications of Transparency for Societal Accountability. Governance, 27(2), 291-320. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12033 [ Links ]

Baume, S. & Papadopoulos, Y. (2018). Transparency: from Bentham’s inventory of virtuous effects to contemporary evidence-based scepticism. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 21(2), 169-192. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698230.2015.1092656 [ Links ]

Berg, K. & Feldner, S. (2017). Analyzing the Intersection of Transparency, Issue Management and Ethics: The Case of Big Soda. Journal of Media Ethics, 32(3), 154-167. https://doi.org/10.1080/23736992.2017.1329017 [ Links ]

Berliner, D. (2014). The Political Origins of Transparency. The Journal of Politics, 76(2), 479-491. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022381613001412 [ Links ]

Camacho, I. (2016). No hay transparencia sin comunicación: hacia un sitio web municipal que comunique. En L. Romero-Rodríguez & R. Mancinas-Chávez (Eds.), Comunicación institucional y cambio social. Claves para la comprensión de los factores relacionales de la comunicación estratégica y el nuevo ecosistema comunicacional (pp. 139-164). Egregius. [ Links ]

Centro de Estudios Públicos-CEP. (2022). Estudio Nacional de Opinión Pública, Encuesta CEP 86, abril-mayo. https://www.cepchile.cl/encuestaCEP [ Links ]

Christensen, L. T. & Cornelissen, J. (2015). Organizational transparency as myth and metaphor. European Journal of Social Theory, 18(2), 132-149. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431014555256 [ Links ]

Consejo para la Transparencia-CPLT. (2019). Estudio Nacional de Transparencia 2019. https://bit.ly/3LFnCI2 [ Links ]

Consejo para la Transparencia-CPLT. (2021, 19 de noviembre). Presidenta del CPLT es elegida presidenta de grupo de expertos en Integridad y Anticorrupción de la OECD. https://bit.ly/48simRJ [ Links ]

Cucciniello, M., Porumbescu, G. & Grimmelikhuijsen, S. (2016). 25 Years of Transparency Research: Evidence and Future Directions. Public Administration Review, 77(1), 32-44. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12685 [ Links ]

Edwards, L. (2020). Transparency, Publicity, Democracy, and Markets: Inhabiting Tensions Through Hybridity. American Behavioral Scientist, 64(11), 1545-1564. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764220945350 [ Links ]

Florini, A. (2000). Does the Invisible Hand Need a Transparent Glove? Research Collection School of Social Sciences. Paper 2092. https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/soss_research/2092 [ Links ]

Given, L. M. (2008). Context and contextuality. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412963909 [ Links ]

Grunig, J. E. & Hunt, T. (1984). Managing Public Relations. Rinehart and Winston. [ Links ]

Hallsby, A. (2020). Psychoanalysis against WikiLeaks: resisting the demand for transparency. Review of Communication, 20(1), 69-86. https://doi.org/10.1080/15358593.2019.1706761 [ Links ]

Hood, C. & Heald, D. (2006). Transparency: the key to better governance? Oxford University Press. http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0725/2007272628-d.html [ Links ]

Hossain, D. (2017). Discourse Analysis: An Emerging Trend in Corporate Narrative Research. Middle East Journal of Business, 12. https://doi.org/10.5742/mejb.2017.93084 [ Links ]

Huberman, A. M. & Miles, M. B. (1994). Data management and analysis methods. En N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 428-444). Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Lee, T. H. & Boynton, L. A. (2017). Conceptualizing transparency: Propositions for the integration of situational factors and stakeholders’ perspectives. Public Relations Inquiry, 6(3), 233-251. https://doi.org/10.1177/2046147X17694937 [ Links ]

Lehr-Lehnardt, R. (2005). NGO Legitimacy: Reassessing Democracy, Accountability and Transparency. Cornell Law School Inter-University Graduate Student Conference Papers, Paper 6. http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/lps_clacp/6 [ Links ]

Macnamara, J. (2016). Organizational listening: Addressing a major gap in public relations theory and practice. Journal of Public Relations Research, 28(3-4), 146-169. https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726x.2016.1228064 [ Links ]

Meijer, A. (2013). Understanding the Complex Dynamics of Transparency. Public Admin Review, 73(3), 429-439. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12032 [ Links ]

Ministerio de Hacienda. (2022, 27 de septiembre). Ley 20.393. Establece la Responsabilidad Penal de las Personas Jurídicas en los Delitos que Indica. Biblioteca del Congreso de Chile. https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1008668 [ Links ]

Ministerio Secretaría General de la Presidencia. (2021). Integridad, probidad y transparencia en Chile. Tres décadas de avances y desafíos. Ministerio Secretaría General de la Presidencia. https://www.integridadytransparencia.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/IN-TEGRIDAD-PROBIDAD.pdf [ Links ]

Morales Quiroga, M. (2020). Estallido social en chile 2019: participación, representación, confianza institucional y escándalos públicos. Análisis Político, 33(98), 3-25. https://doi.org/10.15446/anpol.v33n98.89407 [ Links ]

Parris, D., Dapko, J., Arnold, R. & Arnold, D. (2016). Exploring transparency: a new framework for responsible business management. Management Decision, 54(1), 222-247. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-07-2015-0279 [ Links ]

Peruzzotti, E. & Smulovitz, C. (2002). Accocuntability social: la otra cara del control. En E. Peruzzotti (Ed.), Controlando la Política. Ciudadanos y Medios en las Nuevas Democracias Latinoamericanas (pp. 23-52). https://controlatugobierno.com/archivos/bibliografia/PERUZZOTTIcontrolando_la_politica_caps_1_2_y_3.pdf [ Links ]

Plaisance, P. L. (2007). Transparency: An Assessment of the Kantian Roots of a Key Element in Media Ethics Practice. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 22(2-3), 187-207. https://doi.org/10.1080/08900520701315855 [ Links ]

Rodríguez, D. & Opazo, P. (2007). Comunicaciones de la organización. Ediciones UC. [ Links ]

Sadi, G. & Méndez, V. (2015). Una aproximación histórica al dominio intelectual de las Relaciones Públicas. Tensiones paradigmáticas en su construcción disciplinar. Revista Internacional de Relaciones Públicas, 5(10), 47-66. https://doi.org/10.5783/revrrpp.v5i10.353 [ Links ]

Sandoval, C. (1996). Investigación Cualitativa. Instituto Colombiano para el Fomento de la Educación Superior [ICFES]. https://www.academia.edu/15022941/Investigaci%C3%B3n_Cualitativa_Carlos_A_Sandoval_Casilimas [ Links ]

Schauer, F. (2014). Transparencia en tres dimensiones. Revista de Derecho (Valdivia), XXVII(1), 81-103. https://www.revistaderechovaldivia.cl/index.php/revde/article/view/440 [ Links ]

Schnackenberg, A. K. & Tomlinson, E. C. (2016). Organizational Transparency: A New Perspective on Managing Trust in Organization-Stakeholder Relationships. Journal of Management, 42(7), 1784-1810. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314525202 [ Links ]

Shocker, A. D. & Sethi, S. P. (1973). An Approach to Incorporating Societal Preferences in Developing Corporate Action Strategies. California Management Review, 15(4), 97-105. https://doi.org/10.2307/41164466 [ Links ]

Tabuyo, M. G., Sáez, A., Cañadas, J. A. & Saraite, L. (2019). Políticas públicas de transparencia en Sudamérica. ¿Regulación estricta o regulación laxa? Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 25(1), 224-235. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=28065583014 [ Links ]

Teddlie, C. & Yu, F. (2007). Mixed methods sampling: A typology with examples. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1), 77-100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689806292430 [ Links ]

Wehmeier, S. & Raaz, O. (2012). Transparency matters: The concept of organizational transparency in the academic discourse. Public Relations Inquiry , 1(3), 337-366. https://doi.org/10.1177/2046147X12448580 [ Links ]

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. Sixth edition. SAGE. [ Links ]

1This article is part of the doctoral dissertation entitled: Strategic Communication and Organizational Transparency: A Relational Perspective Approach to Public and Private Organizations in Chile. It is funded by the Chilean National Agency for Research and Development (ANID-Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo).

3This concept refers to the set of processes that allows for the efficient and sustainable governance of a country or institution.

5Some examples of private sector cases are: La Polar, the collusion of pharmacies, and the collusion in the sale price of toilet paper.

6Law 20.393 establishes that legal entities will be liable for crimes committed by their owners, controllers, managers, chief executives, representatives or personnel involved in management and supervision activities for the benefit or in the interest of the entity. See Ministerio de Hacienda (2022).

7In the last 20 years, a series of international standards have emerged that promote the development of sustainable practices for organizations in the environmental, social, and governance fields, such as: Global Reporting Initiative, Dow Jones Sustainability Index, Fairtrade Labeling, State of Sustainability Initiatives (SSI), among others.

8Quotes are accompanied by three numbers (two digits each) separated by dashes. The first refers to the organization, the second to the informant number and the third to the segment of the text analyzed.

9This approach does not refer to those cases that are settled by the Consejo para la Transparencia (CPLT), in its capacity as an autonomous body to settle matters of this nature. Notwithstanding the above, there is a broad spectrum of other matters that do not reach the CPLT, and whose inflection point is established by the legal dimension, leaving transparency needs out of this discussion.

How to cite: Bravo-Maggi, P. I. (2023). What Do Chilean Organizations Mean When They Claim to be Transparent? Comunicación y Sociedad, e8559. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2023.8559

Received: January 06, 2023; Accepted: August 31, 2023

text in

text in