Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Comunicación y sociedad

Print version ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc vol.19 Guadalajara 2022 Epub Oct 03, 2022

https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2022.8130

Articles

Prácticas colaborativas de conocimiento y movimientos sociales

#ElOrgulloPermanece in the face of the pandemic. Mexican LGBT+ users, networks and content on Twitter

1 Universidad Tecnológica de México, Campus Online, México. raul.olmedo@politicas.unam.mx

A network product of the virtual march of LGBT+ Pride in Mexico City is analyzed in the context of COVID-19. Through the Social Networks Analysis (SNA), 7 558 nodes and 13 527 interactions were collected around the hashtag #ElOrgulloPermanece during June 2020. Among the results, it stands out that the users with the greatest relevance on the Internet are producers of LGBT+ content, who together with other users build a collective sense through the interaction and dissemination of said content. These communicative practices are part of contemporary activism.

Keywords: Activism; social movement; communicative practice; LGBT+; social networks

Se analiza una red producto de la marcha virtual del Orgullo LGBT+ de la Ciudad de México ante el contexto de la COVID-19. Mediante el Análisis de Redes Sociales (ARS) se recolectaron 7 558 nodos y 13 527 interacciones alrededor del hashtag #ElOrgulloPermanece durante junio de 2020. Entre los resultados destaca que los usuarios con mayor relevancia en la red son productores de contenido LGBT+, quienes junto a otros usuarios construyen un sentido colectivo a través de la interacción y difusión de dicho contenido. Estas son prácticas comunicativas que forman parte del activismo contemporáneo.

Palabras clave: Activismo; movimiento social; práctica comunicativa; LGBT+; redes sociales

Um produto de rede da marcha virtual do Orgulho LGBT+ na Cidade do México é analisado no contexto do COVID-19. Por meio da Análise de Redes Sociais (ARS), foram coletados 7 558 nós e 13 527 interações em torno da hashtag #ElOrgulloPermanece durante junho de 2020. Entre os resultados, destaca-se que os usuários com maior relevância na rede são produtores de conteúdo LGBT+, que junto com outros usuários constroem um sentido coletivo por meio da interação e disseminação do referido conteúdo. São práticas comunicativas que fazem parte do ativismo contemporâneo.

Palavras-chave: Ativismo; movimento social; prática comunicativa; LGBT+; redes sociais

Introduction

The context generated by COVID-19 was a crisis on daily life; this social and spatial dislocation reconfigured the society-technology relationship. For social movements, the pandemic context has forced them to rethink their actions in the public space, but especially to accelerate the process of incorporating socio-digital platforms2 with the aim of maintaining their visibility and not losing the spaces and actions they have historically built in society (Portillo & Beltrán, 2021).

For the Mexican Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans (LGBT+)3 movements, the pandemic meant rethinking the use of the Internet and socio-digital platforms as strategic sites to replicate their historic actions in the public space and thus denounce the ways in which stigma and symbolic violence materialized during the pandemic (Fuentes, 2021). In this sense, the digitalization of the Pride March in Mexico City is an action developed by LGBT+ populations to continue, within the pandemic context, with the cyclical and historical nature of the reappropriation of public space by a social movement.

Thus, the first digital march of Mexico City’s Pride acquires relevance both for the creativity and innovation implicit in a programming via streaming of approximately ten hours (Marcha LGBTI CDMX, 2020a), and for the explicit ways in which the attendees participated in this strategy of the repertoires of connective action. In fact, through platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, people challenged by the digital Pride March, members or not of the LGBT+ communities, became users who indirectly collaborated in their co-production by sharing the broadcast and adding their own content.

When analyzing this connective action (Reguillo, 2017), the concept of reticular co-production of content is proposed to refer to an emerging communicative practice4 that made greater sense in the pandemic context. Thus, a theoretical framework is structured from the paradigm of the network and daily life. Then, the Social Network Analysis (SNA) is used to study the interaction around the hashtag #ElOrgulloPermanece,5 whose creation and dissemination was a strategy of the organizers of the digital march, and finally the results are analyzed from the implications that result from this innovative and creative process. In general terms, individual action in the process of disseminating the event and its content allows us to speak of a collective construction of meaning and at the same time of an expanded form of activism located in the communicative and cultural field.

Theoretical framework

The network as a paradigm not only allows addressing the structural and operational phenomena developed on the Internet; on the contrary, its scope transcends the technological and is installed in everyday life and the production of knowledge (Deleuze & Guattari, 2010). Therefore, analyzing daily life during the pandemic is central because it is the place/moment where creativity, knowledge and innovation contributed to the construction of the new normal. Thus, the everyday should not only be thought of as a place of encounter and action, but as an object of study (Lefebvre, 1972).

The analysis of everyday life recognizes the dialectical character of the social sphere (Heller, 1985), as well as the preponderance of the production of meaning to individual and collective sociocultural practices (Ibáñez, 2014). According to Lefebvre (1972), everyday life is composed of repetitions inserted in work, family, individual activities, as well as in the creative activity itself. His analysis involves addressing how “the conditions in which the activities that produce objects or works reproduce themselves, restart, resume their constitutive relationships or, on the contrary, are transformed by gradual modifications by leaps” (Lefebvre, 1972, p. 39).

In this sense, COVID-19 not only came to dismantle the repetition of the everyday, but also deepened the use of technology and modified the lifestyles of LGBT+ populations. This was recognized by those who decided to digitize Mexico City’s Pride March, which led to two significant changes: 1) a new way of organizing and carrying out the march (creative activity); and 2) an expanded and unique way of participating in it. In this way, it is possible to observe that this meaning-creating activity did not develop in isolation but had a collective and collaborative character because of the cycle of content production developed by network-movements on the Internet (Castells, 2015; Hernandez, 2011; Peña, 2017; Reguillo, 2017).

Recent researchs (Olmedo, 2019; Poell & van Dijck, 2018; Reguillo, 2017; Rovira, 2012; Sola-Morales & Sabariego, 2020) identify in some of the current social movements a lattice structure that gives them “an autonomy to develop their advocacy and resistance activities without losing their ability to organize and work with other members at times of conjuncture” (Olmedo, 2021, p. 126).

Thus, thinking about the content generated in and by social movements with a lattice architecture forces us to transcend the logics and tree-like structures of their production. Therefore, the content generated by network-movements not only contributes to the construction of a collective identity that differs from the external (Melucci, 2010), but also has an intrinsic relationship with shared knowledge and collaborative creativity applied to its productive cycle.

Although the content generated by network-movements has a decentralized and ubiquitous nature, its purpose does not end with its materialization. On the contrary, every product must execute its use value to complete its production cycle and start a new one (Marx, 2008). Therefore, the content only fulfills its main function when it is consumed and appropriated by the individuals questioned by it. Hence, distribution, dissemination and consumption are constitutive parts of any productive cycle. If the content created by social movements is not disseminated or appropriated by their members and society, then it cannot contribute to social transformation.

Producing, editing, distributing and consuming digital content involves some knowledge to create, but also some knowledge to operate socio-digital platforms. Thus, the digitalization of Mexico City’s Pride March allows us to recognize the generation of content on the Internet as a communicative practice in the face of the uncertainty generated by the pandemic. Network movements generate and refine content created at the digital level through their expertise in everyday life and the appropriation of technology, i.e., they learn as they go and advance increasingly towards a strategic appropriation of technology and the Internet (Olmedo, 2021).

Hence, the organization and realization of the virtual march has not only been a creative action, but also involved a co-production of said content by the traditional attendees. Those who viewed the transmission or shared it in their respective profiles were individuals turned into user-operators (Morley, 2008) who shared basic notions to use these interfaces, becoming co-producers when participating: 1) in the distribution of scheduled content; 2) in the creation of own content along with the transmission; and 3) in the collective construction of a discursive and experiential sense when agreeing with said content referring to the achievements, agenda and visibility of the Mexican LGBT+ populations.

Therefore, this paper recognizes the role of the individual who disseminates and shares content through socio-digital platforms as a participant in the content production cycle. In addition to this, since such content is not alien to LGBT+ agendas, this type of participation represents at the same time a form of activism on the part of these emerging user-operators towards such movements.

The content produced and disseminated by a social movement aims to make the demands visible and show the grievance for which they are organized. The structure and meaning of the content developed by the members of a social movement has a counter-hegemonic character. It is created from those who mobilize, eliminating the intermediaries and reinterpretations that sustain the content produced by other actors such as the media. In this way, the process of mass self-communication is expanded (Castells, 2015), with the aim of reaching more people. Thus, the symbols, discourses, images and meanings articulated in a content “entail an extended socialization that configures a new type of interpersonal and mass communication” (Peña, 2017, p. 52).

In this way, thinking of content as a communicative practice developed by the members of a social movement is a way of expanding the notion of activism from its convergent nature with technology and the individual (Castells, 2015; Olmedo, 2019; Pleyers, 2018 ; Treré, 2020).

Thus, there is a collaborative nature in the production and co-production of the first digital march of Mexico City’s Pride. Both the production of content and its dissemination is the result of a communicative practice that demonstrates the innovative capacity (Innerarity, 2011) and the social affordance executed by the user/ operator on the Internet (Bucher & Heldmond, 2018). This participation implies a level of appropriation of socio-digital platforms and the strategic use of their operational logics to create and disseminate LGBT+ content.

Although the co-production of content acquires a lattice character by the network-movements that produce it, this characteristic is strengthened by the notion of network that gives operational sustenance to the Internet (Castells, 2010; Rovira, 2012; Trejo, 1996; van Dijck, 2016). Therefore, placing the digitalization of Mexico City’s Pride March as an activity that creates content and produces meaning in everyday life allows us to recognize that its production cycle and the meaning created by the users-operators are processes that strengthen the conceptual proposal of a reticular co-production of content.

Thinking about this process not only confirms what several authors already mention about the relevance of the network as a characteristic of contemporary society (Castells, 2010, 2015; Deleuze & Guatari, 2010), but also refers to an implicit structure on the Internet and their platforms (Trejo, 1996; van Dijck, 2016). Therefore, the reticular co-production of content is a contingent process by which individuals participate directly or indirectly in the production, editing, dissemination, and consumption of content related to a topic, consolidating their productive cycle and developing processes of socialization through communication. This communicative practice broadens the function of content because being disseminated gives visibility to the social movement and its agenda, while being consumed materializes the ability to articulate a collective sense from individual action. Finally, the analysis of the collaborative practices of network-movements allows us to identify the changes that suppose the flows of information and interaction among users through the content.

Methodology

Social Network Analysis (SNA) was used to collect Twitter interactions to the hashtag #ElOrgulloPermanece. Under this methodology, users are nodes and interactions are the links with which they connect, generating a network. The use of SNA to analyze digital phenomena carries methodological implications, which must be considered for the obtaining, systematization, debugging, visualization and analysis of these intertwined networks (Olmedo, 2020; Ricaurte & Vidal-Ramos, 2015; Torres, 2013). Together with the hashtag, which allows the interaction to be tracked, the following must be considered: a) the collection time; b) the network delimitation; and c) the indicators to be used. These factors were addressed as follows:

Collection time. The data were collected between June 1st and June 30th, 2020 (pride month in several parts of Mexico, including its capital). The NodeXL software and the Gephi software (for the visualization of data) were used.

Network delimitation. Two processes were carried out. First, users outside of Mexico were omitted and, second, the nodes with reflexive links were removed, i.e., links whose beginning and end is the same node. For research purposes, these links do not represent the relational dynamics generated in the lattice co-production of content.

Indicators. The indicators used in the structural analysis of the network were: network density, degree and betweenness. Its use allows analyzing not only the general character of the network, but also the attributes that the nodes acquire from their position in said structure (Aguilar et al., 2017; Paniagua, 2012; Wasserman & Faust, 2013). Table 1 defines the usefulness of these indicators.

Table 1 Usefulness of indicators

| Indicator | Usefulness |

| Network density | It allows recognizing the degree of cohesion between the nodes that have had contact with the hashtag and with other users involved with the content. |

| Degree | It makes it possible to identify the relevance of a node in the network from the number of links it has with others. These links are not enough to have a strategic role in the network if their directionality is not known. This is relevant to be able to know its role in the information flow. |

| In-degree | Links that a user receives or their content. On Twitter, retweets and tags generate these links. |

| Out-degree | Links that emanate from one user to another. On Twitter, tweets and comments to them materialize this type of link. |

| Betweenness | With this indicator it is feasible to recognize the nodes that have a greater diffusion capacity than others. This attribute is linked not only to the number of links it has, but to the directionality of them. Its role in the information flow is relevant because it can broaden or reduce the scope of a content and reorient the original sense/meaning fixation. |

Source: The author.

Based on the methodological delimitations on the data obtained, the network analyzed was composed of 7 558 nodes and 13 527 links. This data generated around #ElOrgulloPermanece made it possible to identify virtual communities and the preponderance of some nodes in the information flow within the network.

Results

Mexico City’s digital Pride March was a strategy developed in the pandemic context to continue and vindicate this historic mobilization of LGBT+ populations (Franco, 2019). The potential infection did not prevent a contingent made up of LGBT+ people and allies from making the journey on the historic route (Gómez, 2020).

The network generated through the hashtag is useful to represent part of the interaction with the (co)produced content. This was a directed network, which means that the directionality of the links within the lattice structure is known. The network density is very low, which indicates that the cohesion of its nodes is minimal. This does not mean that the linking and strengthening of this community is irrelevant for users-operators, but that what the hashtag seeks is to go viral and flood the networks to reach, along with the co-produced content, the largest number of people.

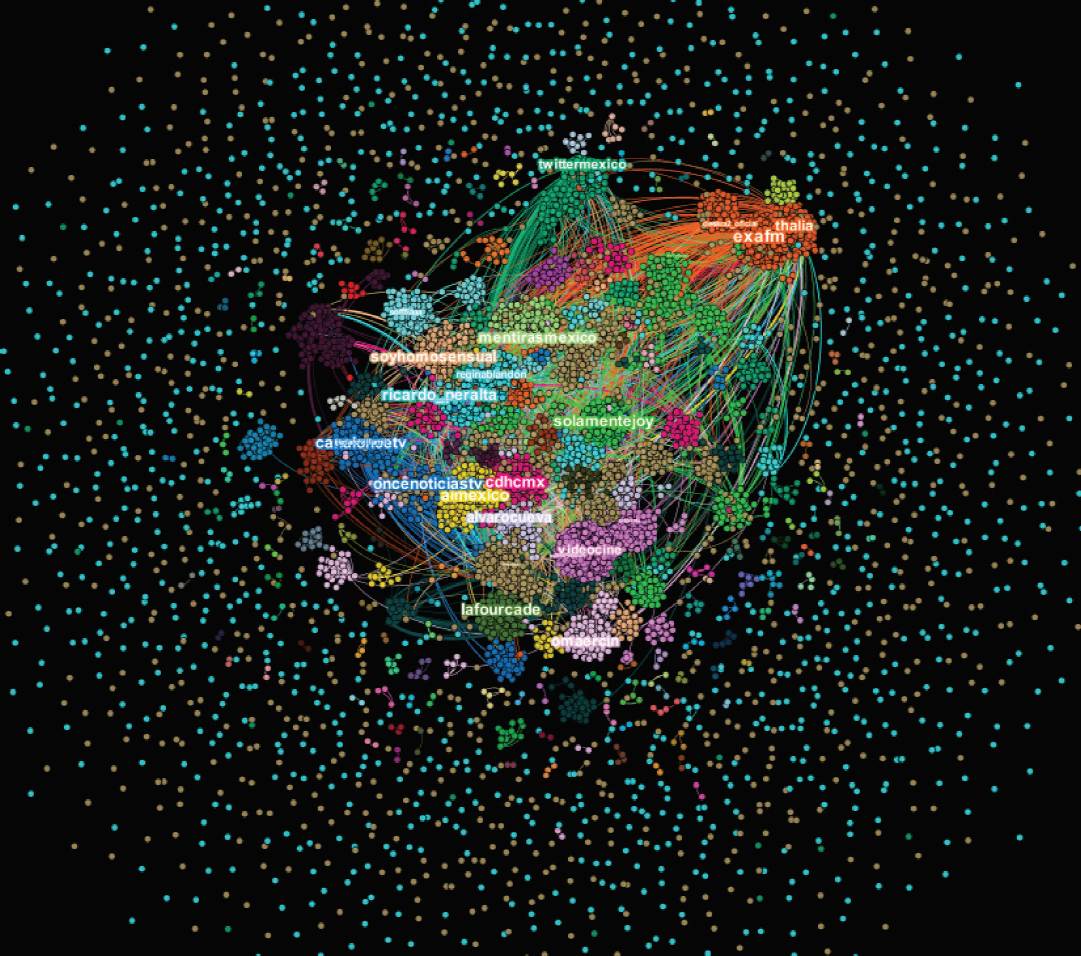

Through interactions, it is possible to recognize virtual communities around #ElOrgulloPermanece. All these subgraphs are linked to each other through the flow of content developed collaboratively alongside the hashtag. In Figure 1, it is possible to see the virtual communities that make up this network.

The presentation of this network is based on the modularity algorithm, with which it is possible to identify the subgraphs (communities) that are interrelated. Each color represents a set of nodes that: a) have a greater link with each other compared to others; or b) are linked to a single node that allows them to connect to the entire network. The names that appear in the graph represent the nodes that have a strategic position in those relevant communities within the lattice structure.

In each community, different users who exercise specific functions in the hybrid context are positioned: LGBT+ digital content creators (marchalgbtcdmx, pepeyteo, soyhomosensual), media (oncenoticiastv, exafm), cultural industries (videocine), activists/ members (rickdelrealoly, omaercin, solamentejoy), allies (thalia, lafourcade), institutions and non-governmental organizations (cdhcmx, iamexico), among others were appealed by the hashtag. Although their roles in the hybrid space are relevant to understand their position, their differentiation with the peripheral nodes is also the result of relational dynamics. The prestige and legitimacy granted by the other nodes contributes to these profiles acquiring a centrality in the network.

With the visualization of the network, it is possible to identify those nodes that fulfill a structural relevance not only for their existence, but for the links they have and their role in information flows. Hence, the selected indicators serve to recognize who is positioned in the network and what their function is. Therefore, Table 2 shows the five nodes with the highest level of degree and intermediation within the network, as well as the breakdown of input and output degrees.

Table 2 Nodes with higher level of degree and intermediation

| User | Role* | In-degree | Out-degree | Degree | Betweenness |

| Nodes with a higher degree level | |||||

| marchalgbtcdmx | LGBT+ content creator | 2 516 | 74 | 2 590 | 1 432 024 |

| pepeyteo | 1 531 | 9 | 1 540 | 335 207 | |

| videocine | Mexican film-producing company | 628 | 2 | 630 | 1 057 |

| exafm | Broadcast network digital account | 412 | 14 | 426 | 106 383 |

| reginablandon | Mexican actress | 374 | 5 | 379 | 69 233 |

| Nodes with a higher degree of intermediation | |||||

| marchalgbtcdmx | LGBT+ content creator | 2 516 | 74 | 2 590 | 1 432 024 |

| pepeyteo | 1 531 | 9 | 1 540 | 335 207 | |

| ososmusculososm | 35 | 44 | 79 | 179 796 | |

| rickdelrealoly | 74 | 35 | 109 | 121 620 | |

| johnnycarmona | 36 | 35 | 71 | 113 695 | |

* The role has been obtained from the public and presentation information that each profile has in Twitter.

Source: Elaborated with Gephi, data obtained by the author.

All content and interaction are linked to each other by the #ElOrgulloPermanence hashtag. In addition to the content that is articulated with the hashtag, the public nature of the users-operators and the platform where they interact before, during and after the event is evident. This parallelly increases the visibility of discourses emanated and co-produced by LGBT+ populations, questioning stigma and reaffirming their legitimacy in the public (digital) space.

On the other hand, the betweenness allows us to observe that some nodes become hubs (Barabási, 2011). These fulfill an amplifying function both for their links and for their ability to call in their followers and/or people they follow. In this way, the @marchalgbtcdmx account is consolidated as a node that has the largest number of links and a great centrality in the dissemination of information within the network formed around the hashtag #ElOrgulloPermanece. Figure 2 shows the publication of @marchalgbtcdmx with the highest interaction.

The relevance of hubs is structural and informative, i.e., without them many nodes would not quickly access the content, since they would have to wait for the information flow to arrive by another way. In the worst case, they would be isolated by the information dependence derived from their reduced interconnection. Figure 3 shows the reconfiguration of the network without the five nodes with the highest betweenness.

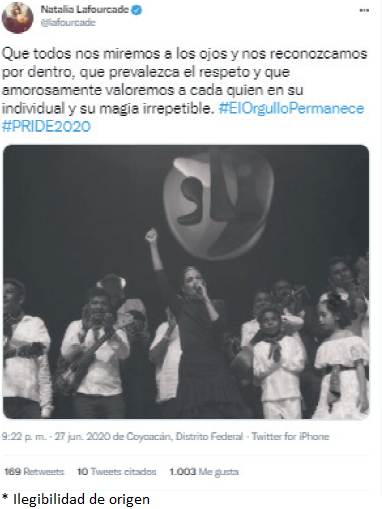

By omitting these hubs, the network reduces its links by 32.7%, which demonstrates the ability of connection and intervention of this type of nodes in a network of this nature. Of the nodes with a high degree of intermediation, the role they play in the digital space stands out. They are all content creators for Mexican LGBT+ populations, which also influences that their position is more creation-dissemination and that the amount of their input and output links tend to balance. Finally, it is important to show that publication with the most interaction that does not belong to the strategic nodes (Figure 4).

Its relevance lies not only in its scope, but in the own and original content that is added to the hashtag. Thus, the reticular co-production of content allows building a collective meaning that challenges other users, motivating their participation in the productive cycle and making them part of a collaborative action on the Internet.

Discussion and conclusions

The digital Pride March and the journey of its historic route shows that there is no contradiction between these contemporary forms of activism. On the contrary, the repertoires of connective action are complemented by actions in the public space. Both strategies derive from the objectives of the network movements and their context. Currently it is difficult to think of a repertoire of action that is not mediated by technology or mediated by the network paradigm (Pleyers, 2018; Reguillo, 2017; Rovira, 2012).

In fact, this form of communication and network action not only decentralizes the supply of the sphere and public opinion by mass media, but also turns the user-operator into a producer and receiver of the content (Morley, 2008).

Contrary to the forced idea of maintaining a border between offline and online strategies, it is necessary to think of contemporary activism with a hybrid character and as a product of the convergence of the subject’s skills, interests and technological appropriations (Sierra Caballero, 2020; Treré, 2020). This is manifested through contingent participation in the lattice co-production of LGBT+ content in Mexico City, during the pandemic.

There is research that provides concepts to understand online activism as a convergent and expanded way of participating in the public sphere and space (Hernández, 2011; Olmedo, 2021; Sierra, 2020). The reticular co-production of content and, in general, what is proposed here as soft activism are proposals that aim to account for a contemporary form of participation. These proposals transcend the political and tree-structured nature because they focus on the cultural and communicative field through the produced content and the individually and collectively articulated meaning.

In light of the perspective that questions the usefulness of this form of participation (Fuchs, 2015; Han, 2016), there is a view that restricts the empirical, and therefore conceptual, change that activism is suffering with network movements. It is therefore important to reinforce these two conceptual proposals.

On the one hand, it is important to note that the user who interacts with the content does not become an activist per se, but their participation in the content production cycle (creation, editing, dissemination or consumption) is a form of activism, specifically soft activism. This is a substantial difference with other conceptual proposals such as click activism (Hernández, 2011), and at the same time it represents an overcoming of the passive gaze that characterizes the pessimistic criticism of these forms of action (Han, 2016). The lattice co-production of content is not limited to the interaction of users mediated by the interface of the platforms, nor does it reduce the empirical nature to the passivity that interactivity with the content supposes. This conceptual proposal implies recognizing the collaborative work to produce the content, operational knowledge to use the Internet, the potential participation of users to spread the content with which they interact on socio-digital platforms, as well as the symbolic articulation that users can develop when creating content that reinforces or not the meanings that accompany a text, image, gif, meme or hashtag. In this way, the reticular co-production of content on the Internet integrates other users contingently to increase the visibility of communicative products by taking advantage of the decentralized structure of the platforms.

Parallel to the reticular co-production of content, it is necessary to propose that this participation mode is also the expression of an expanded form of contemporary activism. Sharing LGBT+ content also shows a potential positioning of the user-operator on this movement-network and its agenda. The creation of hubs and the participation of user-operators in the textual/(audio)visual or symbolic construction of a collective sense on the digital plane is the result of a different form of activism. It is not that content dissemination is equated with lobbying actions to modify or create laws with greater inclusion; on the contrary, it has a different purpose by focusing on the communicative, cultural and symbolic sphere.

Thus, in addition to activism focused on the political sphere and social impact, it is necessary to identify the other ways to transform daily life. From the cultural and communicative field, this change is materialized through the reticular co-production of contents and meanings that question the stigma and heteronomy metanarratives. Both types of activism are not in contradiction, they complement each other because they affect different spaces, making the actions of network-movements acquire a ubiquitous character inside and outside the Internet. Therefore, when the user participates in the dissemination or consumption of content, they not only show a use and appropriation of technology, but also express a form of soft activism. This means that the content created by a social movement and disseminated by a user through their profiles is an implicit sample of the positioning, usually positive, of the individual towards the symbols, meanings and, in general, the discourse that the social movement articulates through the content.

Based on what is observed in this work, soft activism is manifested through the reticular co-production of content generated by activists, organizations, media, allies, and LGBT+ populations. In fact, it can be said that the dissemination of content shows how individuals shed the stigma and position themselves, unintentionally, in an activism that undermines the discourse of discrimination through the visibility of alternative content. Therefore, soft activism is in the field of communication and culture since it is also a communicative practice that has an impact on the imaginary and social representations historically and culturally built by people. Content reticular co-production is a concrete form of soft activism. By contributing to the creation and distribution of content that vindicates LGBT+ populations, the user-operator shows a position about a set of sexual orientations and gender identities that have been invalidated from heterosexism and whose consequences have grown during the pandemic (Fuentes, 2021).

Thus, under the gaze of soft activism, each profile, wall and story acquire a new individual and collective meaning: individual because it is the bidirectional window of the subject that is presented and represented through that profile in the hybrid public space; and collective because said account is not isolated, on the contrary, it is situated in the permanent construction of a large network of interaction based on communication.

The analysis presented here adds to other research that identifies how social affordance materializes in social, cultural and communicative practices derived from technological appropriation, strategic recognition of internet network movements, and collaborative, decentralized and ubiquitous work that can be developed by the members of a social movement (Bucher & Heldmont, 2018). In this way, the Internet and socio-digital platforms become articulating spaces for new communicative practices with a sense of visibility of and for LGBT+ communities. The reticular co-production of content is a communicative practice that becomes more relevant from the disruption in everyday life (Lefebvre, 1972), so its study must be extended to the ways in which its repetition allows it to be placed as a daily activity for current social movements.

Hence, what is exposed in this work shows one more edge of the process of the sometimes imperceptible incorporation of technology in everyday life (Pisani & Piotet, 2009). Indeed, the daily use of the Internet and technology derives in communicative practices with which the individual satisfies certain needs. However, regardless of its purpose, a communicative practice is the maximum expression of creativity and innovation of the individual to produce and reproduce their daily lives, whether they are going through a pandemic or not. Thus, the first digital Pride March is a communicative practice that was developed both to reduce the uncertainty of the health contingency, and to experience it in a novel and creative way.

The users-operators’ participation in the co-production of Mexico City’s digital Pride March opens the door to rethink the collaborative role of the person in the action-network. In structural terms, for example, the virtual communities identified do not express the fragmentation of the network. This is to say that all users share an experiential core, which is manifested through the collaborative creation of meanings and discourses that claim the content they share next to the hashtag. On the other hand, sharing the march streaming and, where appropriate, generating content that accompanies it has important effects on the user and their different social networks (Olmedo, 2021). Future research could further explore these effects, especially the modification of social links. Some user-operators may question the content through stigma or discrimination towards those who share it. Regardless of the way content is displayed on socio-digital platforms, there is a potential effect on the user-operator and their social networks on and off the Internet.

Finally, most of those who position themselves strategically in this network are LGBT+ content creators, so its relevance is related to its communicative function, particularly to produce content of interest to these sectors of the population. Therefore, future research could accept these conceptual notions to address the connective action repertoires of network movements to deepen their communicative practices study and how this co-produced content expresses an expanded form of activism present in the 21st century.

REFERENCES

Aguilar, N., Martínez, E. G. & Aguilar, J. (2017). Análisis de Redes Sociales: Conceptos clave y cálculo de indicadores. UACh-CIESTAAM. [ Links ]

Barabási, A.-L. (2011). Introduction and Keynote to A Networked Self. En Z. Papacharissi (Ed.), A Networked Self (pp. 1-14). Routledge. [ Links ]

Bucher, T. & Heldmond, A. (2018). The affordances of social media platforms. En J. Burgess, A. Marwick & T. Poell (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Social Media (pp. 233-253). SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2010). Comunicación y poder. Alianza Editorial. [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2015). Redes de indignación y esperanza. Alianza Editorial. [ Links ]

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (2010). Mil mesetas. Capitalismo y esquizofrenia. Pre-Textos. [ Links ]

Franco, C. A. (2019). El movimiento LGBT en México. Revista Direitos Culturais, 14(34), 275-305. [ Links ]

Fuchs, C. (2015). Culture and economy in the age of social media. Routledge. [ Links ]

Fuentes, M. (2021). Informe: Impacto Diferenciado ante la COVID-19 en la comunidad LGBTI+ en México. COPRED-Yaaj México. [ Links ]

Gómez, C. (2020, 28 de junio). Marcha virtual del orgullo LGBT en tiempo del covid. La Jornada. https://www.jornada.com.mx/ultimas/sociedad/2020/06/28/marcha-virtual-del-orgullo-lgbt-en-tiempos-del-covid-6759.html [ Links ]

Han, B. (2016). En el enjambre. Herder. [ Links ]

Heller, A. (1985). Historia y vida cotidiana. Aportación a la sociología socialista. Grijalbo. [ Links ]

Hernández, M. (2011). Clic Activismo: redes virtuales, movimientos sociales y participación política. Revista Faro, (11), 29-41. [ Links ]

Ibáñez, J. (2014). Por una sociología de la vida cotidiana. Siglo XXI Editores. [ Links ]

Innerarity, D. (2011). La democracia del conocimiento. Por una sociedad inteligente. Paidós. [ Links ]

Lafourcade, N. (@lafourcade). (2020, 27 de junio). Que todos miremos a los ojos... [Tuit]. https://twitter.com/lafourcade/status/1277064924515139588 [ Links ]

Lefebvre, H. (1972). La vida cotidiana en el mundo moderno. Alianza Editorial. [ Links ]

Marcha LGBTI CDMX. (2020a, 27 de junio). 42 Marcha del Orgullo LGBTTTI+ CDMX. Marcha LGBTI CDMX. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HhYgVNcecLY [ Links ]

Marcha LGBTI CDMX. (@marchalgbtcdmx). (2020b , 27 de junio). Hoy hicimos HISTORIA [Tuit]. https://twitter.com/marchalgbtcd-mx/status/1277082107593003009 [ Links ]

Marx, K. (2008). El Capital. Libro I. El proceso de producción del capital. Siglo XXI Editores. [ Links ]

Melucci, A. (2010). Acción colectiva, vida cotidiana y democracia. Colegio de México. [ Links ]

Morley, D. (2008). Medios, modernidad y tecnología. Gedisa. [ Links ]

Olmedo, R. A. (2019). #AmorEsAmor como constructor de redes digitales en el movimiento LGBT en México. Virtualis, 10(10), 109-133. https://www.revistavirtualis.mx/index.php/virtualis/article/view/ [ Links ]

Olmedo, R. A. (2020). Implicaciones metodológicas en el Análisis de Redes Sociales en las redes sociodigitales. Quórum Académico, 17(2), 73-94. https://produccioncientificaluz.org/index.php/quorum/article/view/32758 [ Links ]

Olmedo, R. A. (2021). Cartografías conectivas: un acercamiento a la construcción de redes sociodigitales del movimiento LGBT+. Chasqui. Revista Latinoamericana de Comunicación, (147), 123-142. https://doi.org/10.16921/chasqui.v1i147.4456 [ Links ]

Paniagua, J. A. (2012). Curso de análisis de redes sociales. Metodología y estudios de caso. Universidad de Granada. [ Links ]

Peña, G. (2017). La caracterización tecnopolítica de los movimientos sociales en red. Revista Internacional de Pensamiento Político, 12, 51-75. https://doi.org/10.46661/revintpensampolit.3224 [ Links ]

Pisani, F. & Piotet, D. (2009). La alquimia de las multitudes. Paidós. [ Links ]

Pleyers, G. (2018). Movimientos sociales en el siglo XXI. CLACSO. [ Links ]

Poell, T. & Van Dijck, J. (2018). Social media and new protest movements. En J. Burgess, A. Marwick & T. Poell (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Social Media (pp. 546-561). SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

Portillo, M. & Beltrán D. E. (2021). Efectos de la pandemia por la Covid-19 en las movilizaciones feministas de la Ciudad de México. Revista Mexicana de Estudios de los Movimientos Sociales, 5(1), 6-36. http://www.revistamovimientos.mx/ojs/index.php/movimientos/article/view/250 [ Links ]

Reguillo, R. (2017). Paisajes Insurrectos. ITESO. [ Links ]

Ricaurte, P. & Ramos-Vidal, I. (2015). Investigación en redes sociales digitales: consideraciones metodológicas desde el paradigma estructural. Revista Virtualis, 6(11), 165-194. https://www.revistavirtualis.mx/index.php/virtualis/article/view/119 [ Links ]

Rovira, G. (2012). Movimientos sociales y comunicación: la red como paradigma. Análisis, 91-104. https://raco.cat/index.php/Analisi/article/view/258164 [ Links ]

Sierra, F. (2020). Ciberactivismo y nuevos movimientos urbanos: la producción del nuevo espacio público en la política contemporánea. Perspectivas de la Comunicación, 13(1), 177-202. https://www.scielo.cl/pdf/perspectcomun/v13n1/0718-4867-perspectcomun-13-01-177.pdf [ Links ]

Sola-Morales, S. & Sabariego, J. (2020). Tecnopolítica, recientes movimientos sociales globales e Internet. Una década de protestas ciudadanas. Teknokultura. Revista de Cultura Digital y Movimientos Sociales, 17(2), 195-208. https://doi.org/10.5209/tekn.66241 [ Links ]

Torres, L. C. (2013). Cómo analizar redes sociales en internet. El caso twitter en México. En O. Islas & P. Ricaurte (Coords.), Investigar las redes sociales. Comunicación total en la sociedad de la ubicuidad (pp. 158-169). Razón y Palabra. [ Links ]

Trejo, R. (1996). La nueva alfombra mágica. Usos y mitos de Internet, la red de redes. Editorial Diana. [ Links ]

Treré, E. (2020). Activismo mediático híbrido. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung [ Links ]

van Dijck, J. (2016). La cultura de la conectividad: Una historia crítica de las redes sociales. Siglo XXI Editores. [ Links ]

Wasserman, S. & Faust, K. (2013). Análisis de redes; sociales. Métodos y aplicaciones. Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. [ Links ]

2This term is used to refer to all those spaces of socialization mediated by the Internet and technology. These platforms have a lattice structure. Its operational logics and interfaces stimulate interaction between users and interactivity with content. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, VKontakte, RenRen are some examples. Through these platforms the individual or user-operator replicates, expands or creates links, which together constitute their social, digital and socio-digital networks. See Olmedo (2021).

3It is known that the LGBT+ community expresses itself in social movements that meet the needs of each population it represents. They are united by both the heteronormative grievance based on stigma and the struggle for their legal and cultural rights through hybrid actions on and off the Internet.

4The communicative practice is understood as a routine action that an individual or social group employs to achieve a goal in the field of culture, communication and socialization, and it has a deep subjective and operational nature: subjective because it helps to express interests and satisfy communicative, cultural, identity and daily needs of the individual; and operational because communicative practice is not only a skill, but also an appropriation and integration of technology to (re)produce a meaning or purpose within the framework of individual and collective experience.

6Translation: “We made HISTORY today (pride flag, stars, Mexican flag). #ElOrgulloPermanece #NoAlRetroceso”.

7Translation: “I wish that we would all look each other in the eye and recognize ourselves internally, that respect would prevail, and that we would lovely value each other in our own and unique individuality and magic. #ElOrgulloPermanece #Pride2020”.

How to cite:

Olmedo Neri, R. A. (2022). #ElOrgulloPermanece in the face of the pandemic. Mexican LGBT+ users, networks and content on Twitter. Comunicación y Sociedad, e8130. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v2022.8130

Received: May 10, 2021; Accepted: October 07, 2021; Published: July 06, 2022

text in

text in