Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Comunicación y sociedad

Print version ISSN 0188-252X

Comun. soc n.29 Guadalajara May./Aug. 2017

Articles

Election Campaigns, the Media and their Impact on Civic Engagement of Mexicans in the 2012 Presidential Election

1Departamento de Estudios Políticos y de Gobierno, Universidad de Guanajuato, México.

This article analyzes the impact of media and campaign exposure on civic engagement in the 2012 Mexican presidential election, by carrying out multivariate statistical analyses of data from a national post-election survey on political culture and citizen practices. The results of the study are more consistent with the mobilisation theories than with theories of media malaise.

Keywords: Political communication; election campaigns; media and campaign impact; civic engagement

Este artículo analiza el impacto de la exposición a los medios y las campañas sobre el compromiso cívico en la elección presidencial mexicana de 2012 mediante análisis estadísticos multivariados con datos de una encuesta postelectoral sobre cultura política y prácticas ciudadanas con representatividad nacional. Los resultados son más consistentes con las teorías de la movilización, que con las teorías del malestar mediático.

Palabras clave: Comunicación política; campañas electorales; impacto de los medios y las campañas; compromiso cívico

Introduction

One of the problems of contemporary democracies is the decline of civic engagement of citizens. Although several structural changes contribute to such a process, including large scale economic and socio-cultural transformations, the media and modern mediated political communication may also have an important role (Dahlgren, 2009). The issue of the effects of exposure to media and campaigns messages in civic engagement have generated an intense theoretical debate. While theories of media malaise argue that the impact of expossure to media and campaign messages on political involvement is negative, theories of mobilization contend that media and campaign effects are rather positive. The aim of this study is to assess the impact of consumption of political information through the media on civic engagement during the Mexican presidential election of 2012. The study is based on quantitative multivariate analysis of data from the 2012 Encuesta Nacional sobre Cultura Política y Practicas Ciudadanas (National Survey on Political Culture and Citizen Practices) published by the Secretaría de Gobernación (Ministry of the Interior, SEGOB, 2012).

The analysis of the impact of media and campaign messages on civic engagement in Mexico is a relevant case study because it provides empirical evidence on an emerging democracy, in a field mainly based on advanced democracies, which tend to be characterized by considerable partisan loyalties among the electorate, plurality of channels of political communication, and sometimes strong sectors of print and public broadcast media, or at least relevant as sources of political information for the population, among other factors limiting the impact of media and media-intensive campaigns on political engagement.

In contrast, Mexico is a country with structural factors that may favor negative effects of mediatized political communication on political involvement; including a party system with limited levels of party identification (Díaz Jiménez & Vivero Ávila, 2015); and a television-centric, predominantly private, and highly concentrated media system (particularly in the broadcast television sector) (Huerta-Wong & Gómez García, 2013), which offers a limited plurality of sources of political information to audiences, whose patterns of media consumption are primarily entertainment-oriented (Jara Elías & Garnica Andrade, 2009), to the detriment of news consumption in electronic and print media.

Theories on media and campaign impact on civic engagement

Theories of media malaise

The media malaise approach argues that exposure to the general media, especially to television entertainment and campaign communications involving negativity (in both: political advertising and election news coverage) has a harmful impact on civic engagement, since it limits substantive learning about politics and promotes citizen cynicism, apathy, and political disaffection, which in turn reduces civic engagement (García Luengo, 2009).

Studies using this approach are diverse. Some analyze the effects of strategic game framing and negativity in news coverage on political trust (Cappella & Jamieson, 1997; Fallows, 1997; Kerbel, 1995; Patterson, 1993; Robinson, 1976; Sabato, 1993). And the consequences of negative images of politics and government, which are predominant in media entertainment (Lichter, Litcher & Amundson, 1999, 2000); other researchers focus on the impact of negative advertising on voter turnout (Ansolabehere & Iyengar, 1995), and some other analyze the negative effects of TV entertainment on social capital (Putnam, 1995, 2000) (for a literature review see Delli Carpini 2004)2.

Theories of mobilization

In contrast to the media malaise approach, mobilization theories argue that media and campaign messages contribute to increasing the levels of civic engagement of citizens. One of the most important mobilization theories is the theory of a “virtuous circle”, which contends that, when people are exposed to campaign communications through the media and new media technologies, they tend to increase their levels of political interest and knowledge, their feelings of subjective political efficacy and political and social trust, as well as their involvement in communal and campaign activity (Norris 2000a, Norris 2000b).

From this theoretical perspective, the relationship between political communication and civic engagement functions as a circular mechanism, in which the more active people, with higher levels of political interest and information, and greater sense of political efficacy and political trust, will be those most exposed to political messages from parties and candidates' campaign teams, as well as to political information flowing through the print and electronic media, Internet and social media. In turn, those who are more exposed to the media and campaign communications become more politically engaged. Several studies conducted with data from advanced democracies of Western Europe and the United States (Newton, 2000; Norris, 2000b, 2002a, 2002b), as well as from new democracies of Central and Eastern Europe and Latin America, tend to support this theory (Curran et al., 2014; Schmitt-Beck & Voltmer, 2007; Voltmer & Schmitt-Beck, 2006).

The impact of media channel and media content

Other studies show that media and campaign effects may depend on the type of media (usually distinguishing between electronic and print media), and the type of media content (whether news or entertainment) to which people are exposed. For example, Putnam (1995, 2000) argues that exposure to newspapers tends to increase social capital and political mobilization of citizens, in contrast to the negative consequences of watching entertainment programs on television. According to Putnam (1995), the decline of civic activism in North America is in part due to the increase in the number of hours that individuals watch television, as this reduces time to interact with others. Exposure to television programs has also made people less trusting of others because such programs tend to overestimate the negative aspects of reality.

The analysis of Holtz-Bacha (1990) on the German case concluded that political disaffection occurred mainly among individuals who were exposed to entertainment in the print and electronic media. In contrast, the consumption of news programs on television and reading the political section in newspapers fostered civic engagement. Similarly, the study of Newton (2000) on the United Kingdom shows that reading newspapers was strongly associated with higher levels of political knowledge, interest, and understanding. However, while television news tended to inform and mobilize; exposure to general television showed a weak association with indicators of political disaffection.

Also, Shah, Mcleod & Yoon (2001) found that while some entertainment content may cause a decrease in civic involvement, the use of news media is positively associated with it. Recent research confirms that television news has a positive impact on civic engagement. However, it is the exposure to news and political information on public television, rather than private commercial television, which is most effective in promoting the political engagement of citizens (Aarts & Semetko, 2003; Curran et al., 2014; Strömbäck & Shehata, 2010).

The impact of the internet and social media

Studies on the impact of Internet use on political involvement shed mixed results. While for Putnam (2000) the effect of the Internet is similar to television in that it erodes rather than promotes civic engagement. Other analyses consider that communicative interactions through Internet are a complement of face-to-face interactions and generate greater political participation (Wellman, Haase, Witte & Hampton, 2001). More recently, research has found that there are positive and significant relationships between the use of digital media/Web 2.0 technologies and political knowledge and involvement (Boulianne, 2009; Dalrymple & Scheufele, 2007; Dimitrova, Shehata, Strömbäck & Nord, 2014; Tolbert & McNeal, 2003).

Studies on Mexico

Research on Mexico has found mixed evidence that primarily supports mobilization theories. Most analyses have focused on media impact on different aspects of political engagement of certain sectors of the Mexican population, such as young pre-citizens in the city of Monterrey, Nuevo León (Muñiz & Maldonado, 2011; Muñiz et al.2011; Saldierna & Muniz, 2014)3 and urban youth nationwide during the presidential election of 2012 (Díaz Jiménez & Muñiz, 2017). Only a few studies have examined media effects on civic engagement using nationwide surveys among the general population, during non-election periods (Corduneanu & Muñiz, 2011; Aruguete & Muñiz, 2012).

An example is the study of Corduneanu and Muñiz (2011) which provided evidence of media impact, mainly mobilization effects, by finding a positive and significant association between consumption of television, radio, the print media and Internet as sources of political information, and relevant political attitudes such as political interest, and satisfaction with democracy, feelings of political efficacy, and trust in institutions, based on data from a nationally representative telephone survey. Those who were informed through the radio, newspapers or the Internet, as their primary source of political information showed greater interest in public affairs with respect to those informed through television. However, the impact of television did not turn out to be negative. Similarly, the results of the analysis on the impact of media consumption on internal efficacy suggest that the Internet is the medium that most strongly foster a sense of political efficacy, followed by television, radio and the print press.

Aruguete and Muñiz (2011) also provide evidence supporting the mobilization approach, to the detriment of the media malaise theories. They found that media consumption contributes positively to increase political interest, political trust, and civic participation using regression analysis with data from the ENCUP (2008)4.

Hypothesis

Drawing on the literature review, the following competing hypotheses are examined in this study:

Impact of exposure to political information through the media: H1: Mobilization: Exposure to political information through the mass media (radio, television, and print media), the Internet and social media will have a positive impact on the scale indicators of civic engagement included in the study (political information, political efficacy and trust, social capital, political discussion and campaign activity). H2: Media malaise: Exposure to political information through the mass media, the Internet, and social media will have an adverse impact on indicators of civic engagement. H3: Media type: Exposure to political information through print media, will have a positive impact on indicators of civic engagement. In contrast, exposure to political information through television, Internet and social media, will have a negative impact on such indicators.

Impact of exposure to news and current affairs programs in broadcast and print media: H4: Mobilization: Exposure to news and current affairs programs in broadcast and print media will have a positive impact on indicators of civic engagement. H5: Media Malaise: Exposure to news and current affairs programs in broadcast and print media will have a negative impact on indicators of civic engagement. H6: Type of Media: Exposure to news in print media will have a positive impact on indicators of civic engagement. In contrast, exposure to news and current affairs programs in broadcast media will have a negative effect on such indicators.

Mass media and campaigns in the 2012 mexican presidential election

As in previous presidential contests, in the electoral process of 2012, Mexican political parties and their candidates made intensive use of electronic and print media, as well as the Internet and social media to get their messages across to the electorate (Meyer Rodríguez, Ríos Calleja, Sánchez Nuevo & Bañuelos Ramírez, 2013). However, some studies show an over-exposure of the electorate to political campaigns. Parties in 2012 had a total number of television spots, seven times higher than in the presidential elections of 2000 and 2006 (Delphos, 2013). Although the allocation of TV ads, according to the new regulatory framework of campaigns established in the 2007-2008 electoral reform, do ensure that each political party reached virtually the entire electorate, such distribution was excessive and has often been criticized as a “spotization” of political communication. Political ads “exceeded the number of spots placed by conventional commercial brands by more than 3,000 percent” (Delphos, 2013, p.329). However, the large amount and excessive repetition of the spots, as well as their lack of creativity, led to a high degree of saturation and weariness among voters (Martínez, Cárdenas & Barrueta, 2013).

Other studies show significant levels of negativity and strategic game framing in political advertising (Arellano Toledo & Jara Elías, 2013; Juárez Gámiz & Brambila, 2013). For instance, Juárez Gámiz and Brambila (2013) found that most versions of spots produced by parties during the election followed an “electoral strategies” framing (55.5%) to the detriment of issue framing relating to public security (14.6 %), social policy (13.6%), and the economy (13%). Regarding negative advertising, the Delphos Group analysis shows that “the total number of negative spots during the campaign was 12,186, equivalent to 17.3% of total spots broadcast during the 90 days of the campaign. Negative spots reached 35.2 million people, which implies 95.7% of people aged 18 or more” (2013, p. 350). However, as well as the positive spots, they caused a high degree of weariness and rejection among voters (Martínez, Cárdenas & Barrueta, 2013).

Regarding television news coverage received by all candidates, this was very limited and superficial (Martinez Garza & Godínez Garza, 2013), although predominantly positive and balanced (Juárez Gamíz, 2013; Martínez Garza and Godínez Garza, 2013). In contrast, campaign coverage in the press and, above all, on the talk radio, turned out to be more negative (Juárez Gamíz, 2013). Regarding the digital press, Muñiz (2015) study on the online versions of five national newspapers5 shows a predominance of strategic game frames over issue frames in media coverage of the campaign period. Other studies show low levels of attention (and recall) by citizens regarding news about campaign events. Overall, news about proselytism and campaign events, as well as on the electoral process were those that had the highest percentage of recall among the population, followed by news on attacks or scandals (Maldonado Sánchez & Ortega de la Roquette, 2013).

Some of these analyses argue that such trends had a negative impact on the levels of political involvement of citizens. According to Jara Elias, of the Delphos Group, “the “spotization” seems to serve little to encourage the involvement of citizens in campaigns, which does not benefit the democratic system” (Garnica, 2013, p. 28). Other studies (Meyer Rodríguez et al., 2013) argue that both campaign communication channels, spots and newscasts on radio and television, “constituted indistinct elements of a presidential campaign that matched with the political culture of the population and contributed little to civic engagement and the democratization of the country” (p.45).

Method

The aim of this section is to test the assumptions of the mobilization and media malaise theories and evaluate whether exposure to media and campaign messages promoted or eroded civic engagement of Mexicans in the 2012 presidential election. Multivariate linear regression analyses were carried out in order to assess the direction of statistically significant associations between indicators of exposure to different sources of political information during campaigns and indicator scales of different components of civic engagement of the Mexican electorate, with data from the National Survey on Political Culture and Citizen Practices, ENCUP, 2012 (SEGOB, 2012).

The ENCUP was conducted between the 17th and 28th of August 2012 in urban and rural areas of the country. The sample design was probabilistic, multistage, stratified and, based on the electoral sections set by the Instituto Federal Electoral (IFE) in 2009.The aim of the study population were adult men and women 18 years or older, living in households. The sample size was 3,750 individuals, yielding a margin of error of +/-2.26% at the 95% level of confidence, nationwide. The refusal rate was 84%. The following section describes the scales of dependent and independent variables used in multiple linear regression models, their construction and validation.

Variables

The dependent variable: Civic engagement

Civic (or political) engagement is not an easy phenomenon to define, nor does it lack criticism (see Berger, 2011). For Putnam (1993, p. 86-91) this consists of the “active involvement in public affairs” and includes aspects such as the development of attitudes of political equality, tolerance, solidarity, and trust, as well as voter turnout and participation in voluntary associations, etc. However, here we will use a more operational definition, based on Norris (2002a), who defines it as a multidimensional set of attitudes and forms of citizen participation that include:

“…what people know about politics, their bonds of social capital (measured by social trust and organizational membership), their support for the political system (including attitudes such as political efficacy and trust in government), and the most common types of political activism (including political discussion, voting turnout, and campaign activism)” (p.3).

It should be noted that other authors prefer the term democratic engagement to refer to this multidimensional set, drawing a distinction between the two subtypes that constitutes it: civic engagement and political engagement (Delli Carpini, 2004). This distinction is based on the forms of activism that characterize them. So, while civic engagement refers to "participation-as an individual or a member of a group-intended to address public concerns directly through methods that are outside of elections and government" (Delli Carpini, 2004, p 397); political engagement is defined as "activities intended directly or indirectly to affect the selection of elected representatives and/or the development, implementation, or enforcement of public policy through government" (Delli Carpini, 2004, p. 397)6. However, both political and civic participation require a set of skills and resources, including values, opinions, and attitudes (such as political interest and knowledge) that make them possible. Therefore, “a democratically engaged citizen is one who participates in civic and political life, and who has the values, attitudes, opinions, skills, and resources to do so effectively” (Delli Carpini, 2004, p. 397)7.

Dependent variables: In order to reduce the volume of data and increase the validity and reliability of the various indicators of civic engagement included in the 2012 ENCUP, a principal components factor analysis (not reproduced here) was run on the survey items. The value of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was .89, and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant with a value of 39247.163 (p <0.000), indicating that the items are suitable for this type of statistical analysis. The results revealed that items were grouped into nine dimensions: 1) political trust; 2) participation in (political) associations; 3) participation in (social) associations; 4) campaign activity; 5) political knowledge; 6) political efficacy; 7) social trust; 8) political discussion; and 9) political understanding. I then proceeded to build and validate scales of each dimension as described below:

Political Trust: an additive scale based on a set of questions about the degree of trust in a number of political actors and institutions, using a scale ranging from 0 (no confidence) to 10 (very confident). In order to assess the internal consistency of the scale and confirm whether the items that comprise it are satisfactorily related to each other, we proceeded to calculate the Cronbach's alpha statistic. The result was .93, a high value that confirms the validity of the scale.

Communal Activity (in political and social associations/organizations): an additive index based on the number of social and political organizations to which respondents said they belong or participate in. The value of Cronbach's alpha statistic was .75, indicating that the items are suitable for the scale.

Campaign Activity: an additive scale was built based on survey questions about the degree of involvement of citizens in electoral campaigns. The Cronbach's alpha test yielded a result of .70.

Political knowledge: an additive index was built based on four survey items designed to measure the level of information of citizens about political authorities, institutions, and campaign events during the election. Alpha for the scale was .59.

Political Efficacy: an additive scale was constructed based on survey questions measuring subjective feelings of political efficacy of people and the degree of influence of citizens on government. Alpha for the scale was .74.

Social Trust: a scale was built using survey items about the level of solidarity and interpersonal trust of Mexicans. Despite the Cronbach's alpha test did not indicate high internal consistency (a = .36.), the items were maintained in one scale based on the comparative literature on social trust (see Montero, Zmerli & Newton, 2008) and the factor analysis results.

Political Discussion: an additive index of two items based on questions about the frequency and habits of interpersonal discussion on political issues of respondents was built. Despite the Cronbach's alpha test yielded a low value (a = .40), we decided to keep the two items that make up the scale, because the factor analysis results united them as one component.

Political comprehension: a scale based on the survey question: P1. How complicated is politics for you?

Independent and control variables

Independent variables: Exposure to broadcast and print media, the internet and social media as sources of political information/Exposure to news and information about public affairs in broadcast and print media. The variables were measured by scales on the frequency of exposure to each media as the main source of political information and through scales that measure the frequency of exposure to news and information on public affairs in electronic and print media. Control variables: sex, age, education, socioeconomic status (AMAI), ideology and party identification. The variables age, education, socioeconomic status, and ideology (right) were treated as continuous variables, where higher values represent higher levels of the variable in question.

Analysis and results

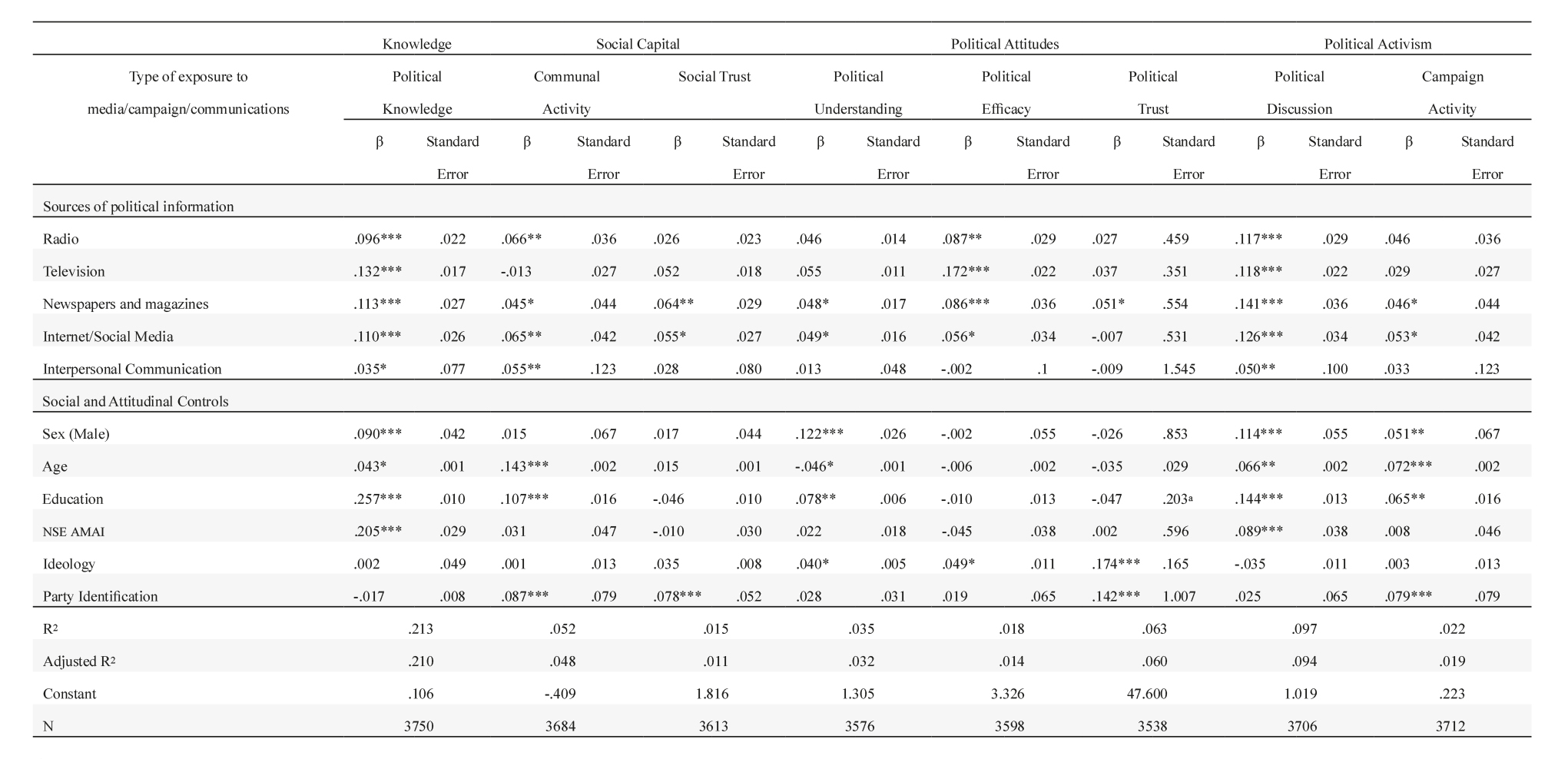

Table 1 shows the results of a series of multiple linear regression models, with the indicator scales of civic engagement as dependent variables and indicators of exposure to different campaign information sources as independent variables. All models include socio-demographic and attitudinal controls. In general, standardized (or beta) coefficients in regression models show that, even after introducing prior control variables, indicators of exposure to political communications are significantly and positively associated with the indicator scales of civic engagement. Contrary to media malaise theories, beta coefficients in regression models reveal statistically significant and positive associations between exposure to the different channels of political communication and the multiple indicators of political involvement. Of the various sources of political information analyzed, reading print media (newspapers and magazines) had the most consistent impact as it proved to be a significant predictor across all eight separate indicators of civic engagement. The use of the Internet and social media for political information also proved significant and positive across all indicators of political engagement, except for political trust.

Table 1 Multiple linear regression models of civic engagement indicators by type of exposure to media and campaign communications.

Note: The table report the values of the standardized (β) beta coefficients of regression models and their p values of statistical significance (***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05, a p= 0.057). Source: 2012 ENCUP.

Exposure to talk radio turned out to have a significant and positive association with four out of the eight indicators of political involvement (political knowledge, communal activity, political efficacy, and political discussion). In contrast to the assumptions of theories of media malaise, television exposure showed no negative effect on any of the indicators of political involvement. In contrast, watching TV was positively related to indicators of political knowledge, political discussion, and feelings of political efficacy. In sum, the results of multiple regression analyses suggest that campaign information flowing through the media strengthen rather than erode civic engagement of Mexicans.

However, in most cases, the values of beta coefficients suggest that associations between exposure to campaign communications and civic engagement indicators were weak or moderate (values lower than .10 in the coefficients are considered as indicators of weak relationships, values between .10 and .20, as indicators of moderate relationships and values greater than .20 as evidence of strong relationships). It should also be noted that, except for the regression model predicting the index of political knowledge, the adjusted r-squared values of regressions were rather low. Which suggests a limited explanatory capacity of the models. Nevertheless, they allow us to assess the positive or negative impact of exposure to campaign communications on civic engagement. The adjusted r-squared value for the regression equation predicting political knowledge was 21 per cent of the explained variance, and the adjusted r-squared of the regression predicting political discussion was almost 10 per cent.

Table 2 shows the results of regression models of indicator scales of civic engagement with exposure to news and information on public affairs in print and electronic media as explanatory variables, with prior social and attitudinal controls. The beta coefficients from the models offer additional evidence mainly supporting mobilization theories, since exposure to newscasts and current affairs programs on the electronic media, as well as to news in newspapers and magazines, has a positive and statistically significant impact in most scales of civic engagement, even after controlling for socio-demographic and attitudinal variables. The models also indicate that attitudinal socio-demographic factors (such as education, age, and socioeconomic status) and attitudinal factors (such as partisanship and ideology) were significant predictors of political involvement of citizens.

Discussion and conclusions

Several studies on political communication have analyzed the role of media and media-intensive campaigns on the decline of civic engagement in contemporary democracies. Although some analysis argue that media and campaigns messages can erode civic engagement (theories of media malaise), other studies claim that the association between exposure to such messages and political engagement is rather positive (theories of mobilization).

However, most research is based on evidence of established democracies rather than emerging democracies such as Mexico, characterized by several structural factors that may favour the negative impact of political messages from the media and media intensive-campaigns on civic engagement, such as a party system with low levels of party identification, a predominantly private and highly concentrated media system, limited levels of political information consumption through the print and electronic media and high levels of primarily entertainment-oriented television consumption among the public, as well as a regulatory framework of campaigns and political advertising which promotes trends such as “spotization”, negativity and strategic game-framing in political advertising and election news coverage.

In this regard, the analysis of the Mexican case can be considered a crucial case study, a most-likely case for theories of media malaise (and a less-likely case for mobilization theories). In order to test both theories and assess the (positive or negative) impact of exposure to diverse campaign information sources on separate scale indicators of civic engagement of Mexicans during the 2012 presidential election, we proceeded to carry out multivariate statistical analyses of the 2012 ENCUP data.

The results of the analyses suggest that, despite the existence of structural factors that might favor negative associations between indicators of exposure to political communication and indicators of civic engagement of Mexicans in the 2012 election, this was not necessarily the case. In contrast to assumptions of media malaise theories, the standarized regression coefficients show that, even after including sociodemographic and attitudinal prior controls, exposure to campaign information through newspapers, radio, television, and the Internet/social media, does not prove any statistically significant negative impact on the different dimensions of civic engagement in Mexico. On the contrary, statistically significant associations between indicators of exposure to different campaign communication channels and civic engagement were always positive. Therefore, the study results suggest that exposure to media messages and campaigns tended to reinforce, rather than erode, civic engagement of Mexicans in 2012. The findings are thus more consistent with mobilization theories in general, particularly with the virtuous circle theory

REFERENCES

Aarts, K. & Semetko, H. (2003) The divided electorate: Media use and political involvement. Journal of Politics, 65 (3), 759-784. [ Links ]

Ansolabehere, S. & Iyengar, S. (1995). Going negative: How attack ads shrink and polarize the electorate. Nueva York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Arellano Toledo, M. & Jara Elías, J. R. (2013). Estrategias de spoteo en el contexto de una nueva reforma. En J. R. Jara Elías & A. Garnica Andrade (Eds.), Audiencias saturadas, comunicación fallida: el impacto de los spots y las noticias en la campaña presidencial 2012 (pp. 31-140). Ciudad de México: Delphi. [ Links ]

Aruguete, N. & Muñiz, C. (2012). Medios de comunicación y actitudes políticas. Un análisis de los efectos del consumo mediático en la población mexicana. Revista Anagramas, 10 (20), 129-146. [ Links ]

Avery, J. M. (2009). Videomalaise or virtuous circle?: The influence of the news media on political trust. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 14 (4), 410-433. [ Links ]

Bennett, S. E., Rhine, S. L., Flickinger, R. S. & Bennett, L. L. M. (1999). “Video Malaise” revisited: Public trust in the media and government. International Journal of Press/Politics, 4 (4), 8-23. [ Links ]

Berger, B. (2011). Attention deficit democracy: The paradox of civic engagement. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Boulianne, S. (2009). Does Internet use affect engagement? A meta-analysis of research. Political Communication, 26 (2), 193-211. [ Links ]

Cappella, J. N. & Jamieson, K. H. (1997). Spiral of cynicism: The press and the public good. Nueva York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Corduneanu, I. & Muñiz, C. (2011). ¿Autoritarismo superado? Medios y actitudes políticas en el contexto mexicano. En C. Muñiz (Coord.), Comunicación, política y ciudadanía. Aportaciones actuales al estudio de la comunicación política (pp. 283-307). Ciudad de México: Fontamara. [ Links ]

Curran, J. et al. (2014). Reconsidering “virtuous circle” and “media malaise” theories of the media: An 11-nation study. Journalism, 15 (7), 815-833. [ Links ]

Dahlgren, P. (2009). Media and political engagement: Citizens, communication, and democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Dalrymple, K. E. & Scheufele, D. A. (2007). Finally informing the electorate? How the Internet got people thinking about presidential politics in 2004. The Harvard International Journal Of Press/Politics, 12 (3), 96-111. [ Links ]

De Vreese, C. H. (2005). The spiral of cynicism reconsidered. European Journal of Communication, 20 (3), 283-301. [ Links ]

De Vreese, C. H. & Elenbaas, M. (2008). Media in the Game of Politics: Effects of Strategic Metacoverage on Political Cynicism. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 13 (3), 285-309. [ Links ]

Delli Carpini, M. X. (2004). Mediating democratic engagement: The impact of communications on citizens’ involvement in political and civic life. En L. L. Kaid (Ed.), Handbook of political communication research (pp. 395-434). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Díaz Jiménez, O. F. & Muñiz Muriel, C. (2017). Los efectos de la comunicación política en el compromiso político de los jóvenes en la elección presidencial mexicana de 2012. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales, LXII (229), 181-222. [ Links ]

Díaz Jiménez, O. F. & Vivero Ávila, I. (2015). Las dimensiones de la competencia en el sistema de partidos mexicano (1979-2012). Convergencia. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 22 (68), 13-49. [ Links ]

Dimitrova, D. V., Shehata, A., Strömbäck, J. & Nord, L. W. (2014). The effects of digital media on political knowledge and participation in election campaigns: Evidence from panel data. Communication Research, 41 (1), 95-118. doi: 10.1177/0093650211426004 [ Links ]

Elenbaas, M. & De Vreese, C. H. (2008). The effects of strategic news on political cynicism and vote choice among young voters. Journal of Communication, 58 (3), 550-567. [ Links ]

Equipo Delphos (2013). Balance 2012 y prospectiva de la comunicación electoral. En J. R. Jara Elías & A. Garnica Andrade (Eds.), Audiencias saturadas, comunicación fallida: el impacto de los spots y las noticias en la campaña presidencial 2012 (pp. 321-362). Ciudad de México: Delphi . [ Links ]

Fallows, J. M. (1997). Breaking the news: How the media undermine American democracy. Nueva York: Vintage Books. [ Links ]

García Luengo, O. (2009). ¿Comunicando desafección? La influencia de los medios en la cultura política. Ciudad de México: Fontamara . [ Links ]

Garnica, A. (2013). Introducción. En J. R. Jara Elías & A. Garnica Andrade (Eds.), Audiencias saturadas, comunicación fallida: el impacto de los spots y las noticias en la campaña presidencial 2012 (pp. 17-30). Ciudad de México: Delphi . [ Links ]

Hanson, G., Haridakis, P. M., Cunningham, A. W., Sharma, R. & Ponder, J. D. (2010). The 2008 presidential campaign: Political cynicism in the age of Facebook, MySpace, and YouTube. Mass Communication and Society, 13 (5), 584-607. [ Links ]

Holtz-Bacha, C. (1990). Videomalaise revisited: Media exposure and Political alienation in West Germany. European Journal of Communication, 5 (1), 73-85. [ Links ]

Huerta-Wong, J. E. & Gómez García, R. (2013). Concentración y diversidad de los medios de comunicación y las telecomunicaciones en México. Comunicación y sociedad, 19, 113-152. [ Links ]

Jackson, D. (2011). Strategic media, cynical public? Examining the contingent effects of strategic news frames on political cynicism in the United Kingdom. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 16 (1), 75-101. [ Links ]

Jara Elías, R. & Garnica Andrade, A. (2009). Medición de Audiencias de Televisión en México. México: Grupo Editorial Patria. [ Links ]

Juárez Gámiz, J. (2013). Índice de cobertura informativa: un análisis de contenido de las notas en los medios sobre los candidatos a la presidencia en 2012. En J. R. Jara Elías & A. Garnica Andrade (Eds.), Audiencias saturadas, comunicación fallida: el impacto de los spots y las noticias en la campaña presidencial 2012 (pp. 142-192). Ciudad de México: Delphi . [ Links ]

Juárez Gámiz, J. & Brambila, J. A. (2013). La publicidad televisiva en el proceso electoral federal de 2012 en Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Derecho Electoral, 4, 303-319. [ Links ]

Kerbel, M. R. (1995). Remote & controlled: Media politics in a cynical age. Oxford: Westview Press. [ Links ]

Lichter, S. R., Lichter, L. S. & Amundson, D. (1999). Images of government in TV entertainment. Washington: Center for Media and Public Affairs. [ Links ]

Lichter, S. R., Lichter, L. S. & Amundson, D. (2000). Government goes down the tube: Images of government in TV entertainment, 1955-1998. The Harvard International Journal Of Press/Politics, 5 (2), 96-103. [ Links ]

Maldonado Sánchez, J. & Ortega de la Roquette, C. (2013). La recepción de los ciudadanos a las noticias de los candidatos. En J. R. Jara Elías & A. Garnica Andrade (Eds.), Audiencias saturadas, comunicación fallida: el impacto de los spots y las noticias en la campaña presidencial 2012 (pp. 249-319). Ciudad de México: Delphi. [ Links ]

Martínez, M., Cárdenas, I. & Barrueta, R. (2013). Recepción e impacto de los spots y la mercadotecnia electoral en los votantes. En J. R. Jara Elías & A. Garnica Andrade (Eds.), Audiencias saturadas, comunicación fallida: el impacto de los spots y las noticias en la campaña presidencial 2012 (pp. 193-247). Ciudad de México: Delphi . [ Links ]

Martínez Garza, F. J. & Godínez Garza, F. A. (2013). La agenda de los telediarios en la contienda del 2012. Derecho a Comunicar, 7, 59-75. [ Links ]

Meyer Rodríguez, J. A., Ríos Calleja, C. I., Sánchez Nuevo, L. A. & Bañuelos Ramírez, R. M. (2013). Significación y efecto de la comunicación mediática en la campaña presidencial de 2012. Revista Mexicana de Opinión Pública, 14, 30-47. [ Links ]

Montero, J. R., Zmerli, S. & Newton, K. (2008). Confianza social, confianza política y satisfacción con la democracia. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 122, 11-54. Recuperado de http://www.reis.cis.es/REIS/PDF/REIS_122_011238570387245.pdf [ Links ]

Muñiz, C. (2015). La política como debate temático o estratégico. Framing de la campaña electoral mexicana de 2012 en la prensa digital. Comunicación y Sociedad, 23, 67-95. Recuperado de http://revistascientificas.udg.mx/index.php/comsoc/article/view/64 [ Links ]

Muñiz, C. & Maldonado, L. (2011). Entre la movilización y el malestar mediático. Impacto de las prácticas comunicativas en las actitudes políticas de los jóvenes. Perspectivas de la Comunicación, 4(2), 32-54. [ Links ]

Muñiz, C., Maldonado, L., Leyva, O., López, R. E., Saldierna, A. R., Hernández, T. & Rodríguez, E. (2011). Hábitos comunicativos y sofisticación política. En C. Muñiz (Coord.), Comunicación, política y ciudadanía. Aportaciones actuales al estudio de la comunicación política (pp. 237-253). Ciudad de México: Fontamara . [ Links ]

Newton, K. (2000). Mass media effects: Mobilization or media malaise? British Journal of Political Science, 29 (4), 577-599. [ Links ]

Norris, P. (2000a). The impact of television on civic malaise. En S. J. Pharr & R. D. Putnam (Eds.), Disaffected democracies: What's troubling the trilateral countries? (pp. 231-252). Princeton: Princeton University Press . [ Links ]

Norris, P. (2000b). A virtuous circle: Political communications in postindustrial societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press . [ Links ]

Norris, P. (2002a). Tuned Out Voters? Media Impact on Campaign Learning, Politeia Conference. Brussels. Recuperado de https://www.hks.harvard.edu/fs/pnorris/Acrobat/Tuned%20Out.pdf [ Links ]

Norris, P. (2002b). Do campaign communications matter for civic engagement? American elections from Eisenhower to George W. Bush. En D. M. Farrell & R. Schmitt-Beck (Eds.), Do political campaigns matter?: Campaign effects in elections and referendums (pp. 127-144). Londres: Routledge. [ Links ]

Patterson, T. E. (1993). Out of order. Nueva York: A. Knopf. [ Links ]

Pedersen, R. T. (2012). The game frame and political efficacy: Beyond the spiral of cynicism. European Journal of Communication, 27 (3), 225-240. [ Links ]

Putnam, R. D. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press . [ Links ]

Putnam, R. D. (1995). Tuning in, tuning out: The strange disappearance of social capital in America. PS: Political Science and Politics, 28 (4), 664-683. [ Links ]

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American Community. Nueva York: Simon & Schuster. [ Links ]

Robinson, M. J. (1976). Public affairs television and the growth of political malaise: The case of “The Selling of the Pentagon”. American Political Science Review, 70 (2), 409-432. [ Links ]

Sabato, L. (1993). Feeding frenzy: How attack journalism has transformed American politics. Nueva York: Free Press . [ Links ]

Saldierna, A. R. y Muñiz, C. (2014). Impacto del consumo de medios de comunicación en las actitudes políticas, experiencias entre estudiantes de bachillerato de Monterrey. En E. Pastor Seller, G. Tamez González & K. A. Saenz López (Eds.), Gobernabilidad, ciudadanía y democracia participativa. Análisis comparado España-México (pp. 209-228). Madrid: Dykinson. [ Links ]

Schmitt-Beck, R. & Voltmer, K. (2007). The mass media in third-wave democracies: Gravediggers or seedsmen of democratic consolidation? En R. Gunther & J. R. Montero (Eds.), Democracy, intermediation, and voting on four continents (pp. 75-134). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Gobernación-SEGOB. (2012). Quinta Encuesta Nacional sobre Cultura Política y Prácticas Ciudadanas (ENCUP). Mexico: Autor. Disponible en http://www.encup.gob.mx/ [ Links ]

Shah, D. V., Mcleod, J. M. & Yoon, S. H. (2001). Communication, context, and community: An exploration of print, broadcast, and Internet influences. Communication Research, 28 (4), 464-506. [ Links ]

Strömbäck, J. & Shehata, A. (2010). Media malaise or a virtuous circle? Exploring the causal relationships between media exposure, political news attention and political interest. European Journal of Political Research, 49 (5), 575-597. [ Links ]

Tolbert, C. J. & Mcneal, R. S. (2003). Unraveling the effects of the Internet on political participation? Political Research Quarterly, 56 (2), 175-185. [ Links ]

Valentino, N. A., Beckmann, M. N. & Buhr, T. A. (2001). A spiral of cynicism for some: The contingent effects of campaign news frames on participation and confidence in government. Political Communication, 18 (4), 347-367. [ Links ]

Voltmer, K. & Schmitt-Beck, R. (2006). New democracies without citizens? Mass media and democratic orientations- a four country comparison. En K. Voltmer (Ed.), Mass media and political communication in new democracies (pp. 199-214). Londres: Routledge . [ Links ]

Wellman, B., Haase, A. Q., Witte, J. & Hampton, K. (2001). Does the Internet increase, decrease, or supplement social capital?: Social networks, participation, and community commitment. American Behavioral Scientist, 45 (3), 436-455 [ Links ]

2Although this theoretical approach has been developed mainly in the United States (Avery, 2009; Bennett, Rhine, Flickinger & Bennet, 1999; Hanson, Haridakis, Cunningham, Sharma & Ponder, 2010; Valentino, Beckmann & Buhr, 2001) it has also been tested in the context of Western European democracies (De Vreese, 2005; De Vreese & Elenbaas, 2008; Elenbaas & De Vreese, 2008; Holtz-Bacha, 1990; Jackson, 2011; Newton, 2000; Pedersen, 2012) and in some new democracies (Voltmer & Schmitt-Beck, 2006).

3The study by Muniz et al. (2011) shows that exposure to the media, especially the press, is positively associated with political sophistication (a composite variable including political interest and knowledge indicators). Similarly, Saldierna and Muñiz (2014) show that exposure to different types of media increases political interest and knowledge. However, their analysis reveal that media exposure also increases the levels of political cynicism. In a more disaggregated analysis, Muñiz & Maldonado (2011) confirmed that exposure to the press was associated with political knowledge, but also with indicators of political cynicism. Meanwhile, exposure to magazines increased political interest and efficacy, and Internet consumption was correlated only with political interest. By contrast, the analysis concluded that exposure to television was negatively associated with higher levels of political knowledge. Regarding the effects of media content, the research found that attention to political content was positively associated with political knowledge, interest in politics and feelings of internal political efficacy. However, attention to entertainment showed mixed results, because it was also positively and significantly associated with political knowledge, but negatively correlated with feelings of external political efficacy.

4It should be noted that the three indicators of exposure to political information via the media, included in the study (exposure to newspapers, radio and television news) had statistically significant effects on political interest. On the contrary, only consumption of radio news had a significant but slight impact on trust in political institutions. Regarding civic participation, consumption of newspapers and radio news had a significant impact on this dimension. By contrast, exposure to television had no significant effect.

6 Berger (2011) also distinguishes between social (or civic) engagement and political engagement. The former refers to the attention and involvement of citizens in activities relating to norms, dynamics and social groups, including diverse forms of activism in voluntary associations; and the later relates to the participation of citizens in government, political processes and institutions, such as voting, political activism and, in general, any kind of engagement whose aim is to influence political decisions of state actors.

7In a similar vein, Dahlgren (2009) argues that democratic participation has as prerequisite civic culture, which consists of six interrelated dimensions: knowledge, values, trust, spaces, practices, and identities.

Received: November 08, 2016; Accepted: January 24, 2017

text in

text in