Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Frontera norte

On-line version ISSN 2594-0260Print version ISSN 0187-7372

Frontera norte vol.35 México Jan./Dec. 2023 Epub Sep 18, 2023

https://doi.org/10.33679/rfn.v1i1.2325

Article

Health Securitization and Immigration Border Control: Title 42 on the U.S.-Mexico Border

1El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, sede Tijuana, México

Title 42 is an old U.S. health policy implemented in the service of immigration control in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. This article aims to discuss the argument about the logic behind the migratory containment strategies involved in this provision. From a documentary and bibliographic review of official data and testimonies of migrants expelled under this policy, the effects of this rule are reviewed, especially towards the populations seeking international protection, who were expelled to territories where their lives were in danger. Three ways of understanding are proposed to critically reflect on how a health policy has been implemented as a migratory restriction: the bionecropolitical governance of migrations, the global regime of security and health immunization, and the securitization of borders through constructing external threats.

Keywords: securitization; migration policies; expulsions; pandemic; U.S.-Mexico border

El Título 42 es una vieja política sanitaria estadounidense instrumentada al servicio del control migratorio a raíz de la pandemia por el COVID-19. El objetivo de este artículo es ensayar una argumentación sobre las lógicas detrás de las estrategias de contención migratoria implicadas en esta disposición. A partir de una revisión documental y bibliográfica de datos oficiales y de testimonios de migrantes expulsados bajo este ordenamiento, se repasan los efectos que esta normativa ha tenido principalmente sobre las poblaciones solicitantes de protección internacional, mismas que fueron expulsadas a territorios donde su vida corría peligro. Para reflexionar de manera crítica en torno a cómo es que una política sanitaria ha podido ser instrumentada como restricción migratoria, se proponen tres vías de comprensión: la gobernanza bionecropolítica de las migraciones, el régimen global de seguridad e inmunización sanitaria y la securitización de las fronteras vía la construcción de amenazas externas.

Palabras clave: securitización; políticas migratorias; expulsiones; pandemia; frontera México-Estados Unidos

INTRODUCTION

Just after the COVID-19 pandemic was declared in March 2020, the U.S. government resorted to Title 42, a dusty health provision that, in practice, operated as another mechanism to reinforce the restrictive immigration regime and tighten the border apparatus between Mexico and the United States. This de facto migration policy had severe repercussions on those seeking international protection by increasing their risks and vulnerabilities, as they were returned to contexts with high criminal incidence. This provision was also selectively implemented, particularly affecting racialized individuals from southern countries, who were reaffirmed as a threat to U.S. security under the order activated by Title 42 (U. S. Code Title 42).

This article reflexively explores an argument about the nature of Title 42 and the cultural, normative, and structural logics behind the strategies of migratory containment that this provision implies. Through an essentially documentary and bibliographic review, three ways of understanding are presented to account for how a health procedure has been able to operate as a migration restriction: 1) the global biopolitical and necropolitical governance of migrations (which particularly affects racialized individuals from countries with colonial experience), 2) the global regime of health security and immunization (which has found its most elaborate expression in the COVID-19 pandemic), and 3) the growing securitization of borders (which relies on the performative and practical construction of external threats where the migrant figure becomes central).

Within this discussion, and drawing on both official data and testimonies from migrants expeditiously expelled under Title 42,2 the article reviews how, following the COVID-19 pandemic, a health policy supported by Title 42 was implemented to serve immigration control. Furthermore, it examines the practical effects that this regulation had on mobile populations and international protection seekers.

The three mentioned axes provide ways to understand how migration policy cooperates with the maintenance and bolstering of a globalized general order based on the functioning of contemporary forms of capitalism and the exclusion of its threats. Title 42 can be seen as a mechanism through which, in exceptional contexts such as the COVID-19 pandemic, these contemporary logics of migration policy have been put into operation. Ultimately, this article aims to shed light on how this policy has reflected that the protection of capital has prevailed over the protection of human rights when it comes to managing global mobilities.

TITLE 42: A HEALTH POLICY SERVING A HIGHLY RESTRICTIVE MIGRATION CONTROL AT THE MEXICO-UNITED STATES BORDER

The cities located in the northern border of Mexico have witnessed the transformations of migratory movements that have passed through them in the last 40 years, and consequently, they have also witnessed the management of population flows that transit through them, where the constant has been border restrictions (Del Monte Madrigal, 2021). Once considered transit cities during the migratory flows of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, they became cities of return and integration for those expelled by the U.S. government during the administrations of Bush, Obama, and Trump. Finally, these cities became spaces of containment where populations seeking international protection were held awaiting the processing of their request or were returned to Mexico under the prerogative of Title 42.

As a result of historical and circumstantial processes, in recent years—especially during the pandemic—these cities have been characterized by hosting diverse migratory profiles whose needs overlap, saturating the reception systems: migrants in transit, deportees, asylum seekers in the United States, refugees in Mexico, internally displaced persons, and unaccompanied minors, among other individuals in situations of mobility. The difficulty of providing assistance to these populations and the risks they face have been aggravated by the implementation of Title 42.

The United States Code compiles federal legislation in the United States and organizes it by subject into 53 titles, of which Title 42 is the compilation that governs matters related to civil rights, public health, and social welfare in the country. Within Title 42, the Public Health Service Act, issued in the mid 1944, is codified, which emerged in response to various epidemic outbreaks of yellow fever, cholera, and tuberculosis that occurred in the first half of the 20th century and is still in effect today. With the aim of preventing highly contagious diseases, Title 42 establishes regulations for implementing quarantines on the entry of any person into the country (U. S. Code Title 42).

In recent months, referring to Title 42 has meant alluding to that provision that restricts the entry of international protection seekers into the United States under the argument of protection against the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the provision invoked by the U.S. government is in Section 265 of that title, which states:

Whenever the Surgeon General determines that by reason of the existence of any communicable disease in a foreign country there is serious danger of the introduction of such disease into the United States, and that this danger is so increased by the introduction of persons or property from such country that a suspension of the right to introduce such persons and property is required in the interest of the public health, the Surgeon General, in accordance with regulations approved by the President, shall have the power to prohibit, in whole or in part, the introduction of persons and property from such countries or places as he shall designate in order to avert such danger, and for such period of time as he may deem necessary for such purpose (U. S. Code Title 42).

It is evident that Section 265 refers to individuals in general who may introduce contagious diseases into the country without specifying their citizenship. Precisely, in the legislative discussion of the Quarantine Act of 1893 (Vanderhook, 2002)—legislation that preceded the one in 1944—any reference to migrants was actively omitted, as even American citizens represented a potential danger of introducing contagious diseases (Guttentag, 2020). The Public Health Service Act of 1944, in effect under Title 42, granted the authorities in charge of health policy the power to quarantine anyone they deemed a source of contagion, regardless of their citizenship. At no point was it intended to provide an outlet for a specific foreign population.

On March 20, 2020, shortly after the declaration of COVID-19 as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and key players in the management of the COVID-19 pandemic, established a health regulation that invoked that section of Title 42 but operated in service of immigration control. The “Order Suspending the Right to Introduce Certain Persons from Countries Where a Quarantinable Communicable Disease Exists” directed its efforts towards any person congregating at federal customs or immigration facilities upon entry into the country. This order served as de facto authorization to suspend any attempts at undocumented entry through the land borders, as well as to request international protection:

This order applies to persons traveling from Canada or Mexico (regardless of their country of origin) who would otherwise be introduced into a congregate setting in a POE or U.S. Border Patrol station at or near the U.S. land and adjacent coastal borders subject to certain exceptions detailed below (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020).

The cornerstone of this order is the public health danger posed by the introduction of such individuals in areas of concentration at or near the borders.

This regulation, based on Title 42, excluded from entering the United States only those people who crossed the land border and who, consequently, would be overcrowded in U.S. federal facilities. However, the order explicitly states the objective of this regulation:

(...) would typically be aliens seeking to enter the United States at POEs who do not have proper travel documents, aliens whose entry is otherwise contrary to law, and aliens who are apprehended at or near the border seeking to unlawfully enter the United States between POEs. This Order is intended to cover all such aliens (CDC, 2020).

As can be observed, the order explicitly differentiates non-citizens as those to whom passage would be restricted.

To leave no doubt, under the protection of this regulation, the Border Patrol requested its agents to expeditiously return these individuals, depriving them of the opportunity to seek international protection, which goes against the provisions of U.S. regulations regarding asylum (Lind, 2020). It is clear that migrants and international protection seekers have been the target of this order.

Title 42 was a regulation that had already been explored during the Trump administration prior to the pandemic. Stephen Miller, Trump’s senior advisor on immigration, had already attempted to invoke this regulation when influenza outbreaks occurred in Border Patrol facilities (Human Rights Watch, 2021). According to Dickerson and Shear (2020), the origin of this policy that uses health regulations as a method of immigration control does not stem from health concerns but rather from xenophobic and exclusionary policies that the White House had at that time.

The call from a significant portion of the epidemiological community on both sides of the border has pointed out that the implementation of Title 42 has not been based on public scientific evidence but on the political attempt to expel populations considered undesirable by the administration (Dearen & Burke, 2020). There were many expressions that exposed the contradiction between a regulation based on a health argument that restricts the entry of specific individuals—international protection seekers at border ports—while allowing a large number of people to continue entering the country. In other words, the aim was not necessarily to stop the spread of the virus, as these actions were selectively applied. In fact, contrary to the claimed argument, their expulsion could potentially turn them into carriers of the virus that could be transmitted across the border (Columbia Public Health, 2020).3

The regulation that activates Title 42 has been amended three times by the Biden administration. In these modifications, unaccompanied children were exempted from expedited expulsion. There have also been several attempts to end this regulation; however, the discussion is currently mired in a legal dispute.4

The most notable consequence of the order to implement Title 42 has been the rejection of hundreds of international protection seekers, despite such action being in violation of the principle of non-refoulment, which is established in both the 1951 Convention of Refugee Statue and U.S. Refugee Act (CIDH, 2015). Those international protection seekers who were expelled under Title 42 had limited opportunities to present their fears of persecution upon being returned. During the pandemic emergency period, the Border Patrol restricted almost any possibility of making an argument to field officers and granted discretion and prerogative to its officers to determine the reasoned credibility of the arguments (Lind, 2020). Although expedited expulsion under Title 42 does not involve a deportation process, it has not been clear how the data collected by Customs and Border Protection on these individuals is being used (American Immigration Council, 2021).

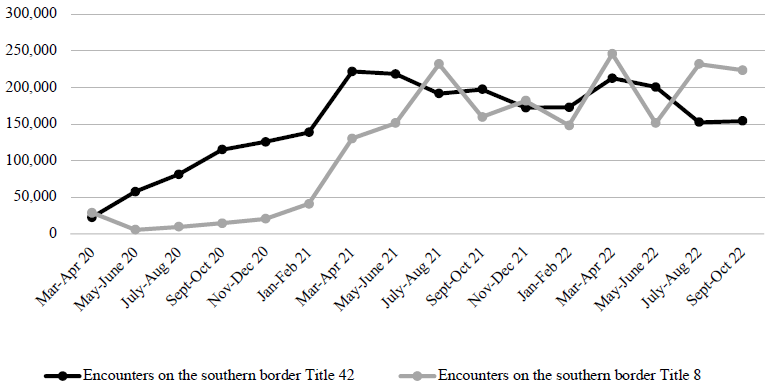

At the time of preparing this document, nearly three years after the pandemic was declared, U.S. Customs and Border Protection recorded over five million encounters—the way they refer to migrant apprehensions—at the southern border of the United States. Of these encounters, half were processed by the immigration authority, referred to as Title 8 in Graph 1, and the other half have occurred under Title 42.

Source: Del Monte Madrigal (2022) based on data from U. S. Custom and Border Protection (2020, 2021, 2022). Own bimonthly update until October 2022.

Graph 1. Apprehensions of Migrants at the Southern Border of the United States During the Pandemic, According to Title 8 and Title 42

Although the numbers have evened out three years into the pandemic, it is possible to observe in the graph that during the first two years of the health emergency (2020 and 2021), the number of migrants returned to Mexico under the provisions of Title 42 has been considerably higher than those carried out based on violations of Title 8 immigration law. This supports the argument that Title 42 has been used as a means of immigration control in the exceptional context of the pandemic at hand. It is in the second half of 2022 that it began to be noticed how returns based on Title 8 start to increase again compared to expulsions under Title 42, and yet the latter still amount to hundreds of thousands, unlike what was happening with those related to Title 8 at the beginning of the pandemic. In this sense, Title 42 has continued to be used as a de facto immigration policy alongside returns under Title 8.

To clarify, during 2020 and 2021, the high number of data associated with Title 42 does not directly refer to the quantity of migrants returned, but rather reflects the number of migrant apprehensions, which could imply that a person attempted to cross multiple times because under Title 42, they are not formally expelled through a deportation process. However, interpreted differently, the deterrent effect sought by Title 42, based on health arguments, has not only been ineffective but has also incentivized crossing attempts, thereby increasing the chances of contagion.

To understand the meaning of the implementation of Title 42 in the United States as a migratory restriction, it is necessary to consider three ways of understanding that, although interconnected, are analytically examined separately in order to provide a specific analysis of the operational mechanisms of this regulation: the global biopolitical and necropolitical governance of migrations, the global regime of health security and immunization, and the construction of threats within the framework of the securitization of national borders. Subsequently, some effects of this policy on the persistent vulnerability experienced by migrant individuals will be highlighted.

Biopolitics and Necropolitics in the Global Governance of Migrations

The international governance of migration refers to the global nature of the migratory phenomenon, where it is advocated that the management of human mobility goes beyond internal processing frameworks and is placed within a multilateral effort (Ghosh, 2000; Mármora, 2002; Castro Franco, 2016). The international migration regime is based on the idea of orderly mobility, driven since the 1990s by various international development agencies, and has found its expressive epitome in the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration adopted in 2018 by a majority of United Nations (UN) member states. The approach to migration management established in these efforts is based, in short, on the orderly and multilateral management and regulation of migrations, as well as the effective administration and channeling of migratory flows. In general, this approach emphasizes administrative processing and multilateral governance through a framework of legal devices, migration and border management infrastructures, as well as state and private actors implementing reception and processing practices.

However, critical readings of this global migration management regime point out the need to interpret these efforts in light of their linkage with neoliberal forms of control and governance of migration. This relationship encompasses technocratic, utilitarian, economic, disciplinary, biopolitical, and necropolitical connotations regarding the management of human mobility between countries, relegating the human rights of migrants to a secondary position, and which ultimately, becomes a global and violent regime of migration control (Overbeek, 2002; Mezzadra, 2005; Geiger & Pecoud, 2010; Estévez, 2020; Varela Huerta, 2020; Domenech, 2017; Ortega, 2022).

These critical poststructuralist-inspired perspectives are concerned with the exercise of power and control over migration and borders within the framework of a social system subordinate to the functioning of a global economic order. To a large extent, they emerge from a Foucauldian interpretative framework where power is exercised through the guidance and domination of behaviors. The analytical interest of these approaches focuses on regulation and control as central instruments of power, particularly in the regulatory mechanisms of the population’s biological processes by the State, which are driven by economic interests and violently exclude populations associated with certain phenotypic and social aspects, resulting in racist and classist management of the migrant population.

Migration regulation, established within the global governance of migrations, manages, controls, constructs, and expels individuals in mobile situations from certain countries based on biopolitical devices, serving the reproduction of the global capitalist economic system (Ortega, 2022). These devices find in national borders a sociopolitical framework where filtering, selection, entry, and stay of individuals in mobile situations and seeking international protection are implemented, constituting a border regime serving the global economic functioning led by developed countries, in which the legality or illegality of migrant individuals is constructed (Casas-Cortes et al., 2014). The externalization of borders, framed in the discourse of global migration governance as a “cooperation mechanism,” is perhaps the clearest expression of how a biopolitical regime of borders crystallizes. Through agreements that transfer unwanted migrants and asylum seekers to “first countries of arrival” or “safe third countries” such as Turkey, Greece, Malta, Mexico, Guatemala, or El Salvador, international protection responsibilities are evaded (Ortega, 2022). The Migrant Protection Protocols in Mexico and Title 42 implemented in the United States are examples of this type of migration management.

The violence in multiple dimensions (state, neoliberal, patriarchal, colonial) involved in the global regime of migration control, particularly in contexts associated with countries with colonial experience, has prompted reflection on how, alongside the regulatory mechanisms for controlling the lives of migrant populations, terror and death are also administered (Estévez, 2020; Varela Huerta, 2020).

The necropolitical perspective (Mbembe, 2011) indicates that, in addition to the regulation of life, the administration of death is used as a governing mechanism in maintaining the globalized neoliberal regime. It operates by constructing and recognizing the subjectivities of colonized peoples (and thus a significant portion of migrant populations) not only as docile, as Foucault argued, but also paradoxically as both productive and disposable. Migrant individuals are used for massive agricultural labor or for development megaprojects and infrastructure construction but are expelled once these projects are completed. Massacres and deaths of migrants occur in territories where para-state logics linked to organized crime operate, confinement spaces where practices of containment, surveillance, and exclusion are enforced, uninhabitable enclaves where the precarization of discarded and immobilized migrant populations intensifies, and so on.

The governmental migratory biopolitics, thus, is not opposed but constitutive of the necropolitical management of migration, since it refers to the way in which state institutions, laws and political norms, civil society organizations, judicial mechanisms, and various forms of bureaucracy collaborate in the administration of migrant individuals through different strategies of selective inclusion, but above all, widespread exclusion that, ultimately, by disregarding their responsibility for protection, they contribute to the precarization and abandonment of these populations, leading to their death (Estévez, 2020). In other words, on one hand, there are the biopolitical legal devices that are selectively operated judicially based on racial and social profiling, and on the other hand, there are the necropolitical devices in their multiple dimensions. These range from extreme acts such as massacres and femicides, to the criminalization of movement or the construction of detention centers with carceral practices, and even the legal disengagement from assumed responsibility for protection.

Title 42 can be understood as a biopolitical and necropolitical mechanism that, in the context of the pandemic, has operated in the multilateral management and exclusion of mobilities at the Mexico-U.S. border, by allowing border agents to selectively deny international protection processes and expel asylum seekers from U.S. territory to violent territories, while also collaborating with Mexico and other southern countries in their channeling and assistance. This is the case of Miriam, an internally displaced person who fled from Michoacán due to the confiscation of her belongings and threats from criminal groups. When she attempted to seek asylum, she was returned to Tijuana under Title 42. She shares her experience:

(…) we decided to stay there [in El Chaparral]—we bought a small camping tent—(…), it’s a mess in El Chaparral, they fight among themselves, it’s very ugly, it smells very bad, and one can't stand being there (…) we paid 100 or 200 pesos a day to use the bathroom. We paid because there are some bathrooms there—as support—but they weren’t clean, to be honest. (…) There is a lot of danger there [in El Chaparral]. Children are stolen, and there is a lot of danger (Miriam, personal communication, July 2021).

This testimony, along with others later collected, illustrates how the health argument was used as an instrument of migration control, as it highlights the health risks faced by people who remain on the southern side of the border. In this sense, there is a clear biopolitical and necropolitical disregard for international protection, as well as the lethal endangerment of the bodies of vulnerable populations in highly dangerous contexts.

Global Regime of Health Security and Immunization

The COVID-19 pandemic has aligned well with these biopolitical and necropolitical mechanisms of global migration management, not only because efforts to contain the SARS-CoV-2 virus have served as the missing pretext to build administrative walls against migration and asylum in the United States, but also because they are part of a history of medicalization of international relations and epidemiological surveillance driven by developed countries, activated through Title 42 as a form of health immunization against contemporary migratory flows.

The expulsion of migrant populations on health grounds in the United States is not something new or unique to this pandemic; it is a practice that has been carried out since the 19th century, selectively based on racial differentiations and moralizing nativist ideologies. The anti-Chinese campaigns in the late 19th century United States, driven by nativist ideologues who blamed Chinese migrants for epidemics such as leprosy, malaria, or chickenpox—migrants who faced harassment, segregation, violent coercion, and public ridicule—ultimately resulted in the expulsion of these populations not only from towns but from the country itself, as well as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (Shah, 2001). In the early 20th century, bolstering these nativist ideas, scientific discourses popularized the notion that racial and national group differences possessed innate biological characteristics. From this, the intersection of eugenics, public health, and migration led to the creation of inadmissible subjects deemed susceptible to carrying communicable diseases, and thus profiles of deportable individuals began to be delineated based on their biological characteristics (Goodman, 2020). Throughout the 20th century, Chinese, Irish, Jewish, Italian, Haitian, Mexican, and African migrants, among others, have been subjected to expulsion and/or containment policies, being linked as a threat associated with various epidemic diseases such as tuberculosis, diphtheria, chickenpox, yellow fever, Ebola, or HIV, among others. All of this has contributed to the fabrication of the migrant stigma as a health threat that carries germs, viruses, and bacteria unknown to Americans (Kraut, 1994).

In addition to recognizing these biopolitical, racializing, and exclusionary actions against migrant populations based on pseudo-sanitary arguments, it is possible to understand how an international epidemiological surveillance was organized from countries in the global North with the purpose of health immunization in these territories; resulting in a geopolitical organization of globalized health security, devised from specific countries. According to Aldis (2008), health is a concern in international politics that justifies global cooperation in sanitary matters, but with claims of security, it emerges as part of a historical development of 200 years, where global health policies have expanded based on locally rooted techno-scientific knowledge—product of Western hegemonic science—which has been universalized by international medical authorities. In this regard, King (2002) suggests that a racist and colonial medical hegemony that serves as the foundation for global health authorities to intervene locally within that established order.

The medicalization of international relations has developed through various channels such as diplomacy, medical and health cooperation, as well as military operations and so-called humanitarian interventions (De la Flor, 2018). It is through these avenues that the medicalization of security and the pursuit of health immunity have been shaped. This is achieved by framing and organizing contagious diseases (such as Ebola, HIV, COVID-19, among others) as threats to international security.

In the 1990s, U.S. health and security experts recovered the concept of “emerging infectious diseases,” a term coined by renowned virologist Stephen Morse in 1989 to acknowledge viral threats to U.S. public health and assess the risks posed by the emergence of relatively unknown viruses to national security and the country’s commercial interests. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which have played a crucial role in managing the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States and worldwide, have been at the forefront of institutionalizing the link between security and health. It was argued from there that these emerging viral diseases could pose a threat not only to the nation’s public health but also to its international commercial, political, and economic interests (King, 2002).

Once the concept of emerging infectious diseases was put to the test, the CDC incorporated health matters as a priority of U.S. national security. Efforts and resources from research centers and security agencies were focused on establishing a global surveillance procedure to address what was considered a threat to their security. “Thus, between 1995 and 2005, the two main strategies that make up the current Global Epidemiological Surveillance System were created: the GOARN (Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network) system and pandemic preparedness” (De la Flor, 2018, p. 52). These epidemiological surveillance strategies based on securitization tactics, proposed by the two economically most powerful North American governments, were adopted by the World Health Organization (Organización Mundial de la Salud [OMS], 2007), which defined global health security as:

the activities required, both proactive and reactive, to minimize the danger and impact of acute public health events that endanger people’s health across geographical regions and international boundaries (OMS, 2007, p. 9).

A regime of biopolitical governance was constructed in association with the narrative of global health security, and national borders gained greater importance in the securitization of health, thanks to the pressure exerted by the U.S. and Canadian governments on the WHO (Davis, 2008; Basile, 2020b). The use of the adjective global in this strategy is a way to universalize what hegemonic countries consider as health threats. Evidently, according to Davis (2008), global governance as a measure to address emerging infectious diseases has benefited the interests of countries in the so-called global North, as their priority is to protect their citizens through epidemiological surveillance that keeps epidemics outside their borders. In this sense, the global epidemiological surveillance apparatus would be more of a geopolitical instrument that, with the consent of the WHO, favors Western states (De la Flor, 2018).

If this regime of health security and immunization is globally oriented by the WHO but driven by the U.S. government, Pan-American health cooperation is no exception and can be seen as a regional mechanism to organize epidemiological surveillance and pandemic management, guided by the interest of maintaining U.S. political, military, and economic hegemony in the region. According to Basile (2020a), the idea of Pan-Americanism finds its correlation in epidemic statistics when referring to “The Americas” as a whole, but always guided from Washington, where vertical campaigns have been organized for disease control and elimination in the region.

The relationship between health and security presents collective health as a means of maintaining global security. Various authors, working from a critical epidemiology perspective, have argued that medical language converges with a military logic, and it is often the military who have been responsible for implementing security interventions in health matters5 by employing militaristic language, whether against opponents in a war or in response to the danger posed by a global infectious disease (Basile, 2020a; De la Flor, 2018; Breilh, 2010). In that sense, it is possible to consider a colonial, imperialistic, and militaristic logic in the construction of this regime, which continues to operate in the implementation of policies such as Title 42.

Parrini (2015) pointed out, based on ethnographic work in the southern border of Mexico, that medical devices function as surveillance mechanisms at the border to maintain social and health boundaries, segregating migrants who are constructed as potential carriers of dangers to the local society. This largely involves the health regulation of bodies, where medical science and the policing apparatus become indistinguishable. However, epidemiological surveillance necessarily involves the control of populations in mobility, considered as viral threats. This becomes a paradox of institutional action, as security corporations aim to exclude irregular migration from the territory, while medical institutions need to have sedentary control over it. The difference with Title 42 is that it managed to erase this paradox by becoming a biopolitical regulation that, in discourse and practice, both excludes populations in motion and maintains epidemiological surveillance over these bodies. According to Mbembe (2019), “this redistribution of life into distinguishable scales of healthiness and unhealthiness is a key dimension of contemporary migration regimes” (p. 11).

The arguments put forth to activate section 265 of Title 42 respond to this framework of securitization of health that equates health threats with threats to national security. This not only impacts the sensitive border region but also falls within the realm of a logic of biopolitical migration control. Thus, the deportations of migrants that have occurred over the course of two years of the pandemic under the restriction of Title 42 are not related to violations of immigration regulations but rather to the regime of health security and immunization, which paradoxically has served the purpose of migration control in the past two years.

It is important to mention that not all migrants and asylum seekers were expelled under Title 42, but only those considered susceptible to overcrowding at land-based migrant stations, specifically impoverished individuals from Central America, South America, the Caribbean, and Africa, according to the CDC (2020). For those traveling by air or sea with resources, this rule did not apply. The racialized difference has been notable regarding the preferential treatment received by asylum seekers from the Russo-Ukrainian war, where it has been observed in March 2022 how, while these populations from Ukraine are granted immediate access without being subject to Title 42, individuals from countries in the Global South have been denied entry under this prerogative. This can be interpreted within the immunization logic proposed by Roberto Esposito (2006), in which the body of the State is “immunized” with doses of migrants who are considered non- threatening, racially compatible, or simply suitable for the reproduction of the economic system. Those impoverished migrants have been deemed a security threat to the northern country and have been expelled despite the risks it entails.

The Construction of Threats and the Securitization of Borders

According to Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe (2019), at the same time an era of planetary entanglement is being experienced, where proximity and exposure to other bodies are more prevalent than ever due to globalizing processes that underpin contemporary forms of capitalism, strong processes of contraction are also being experienced, as well as containment, and enclosure, which result in the division of regions, the construction of walls, and the process of bordering. Through these mechanisms, certain spaces become impossible to cross for undesirable populations, who are often subjected to processes of racialization and come from countries with colonial experience.

According to Mbembe (2019), this is because the experience of proximity and closeness is seen not as a possibility or opportunity, but as an exacerbated risk to the reproduction of the social, political, economic, and cultural system. This has resulted in the construction of walls and enclaves of segregation whose function is to slow down and/or halt the movement of certain populations in order to manage the risk of proximity. National security, therefore, is the most commonly cited reason to justify the commitment of certain countries, such as the United States, to strengthening their borders.

The securitization of contemporary borders is a parallel project that supports and consolidates the functioning of a globalized neoliberal model driven by Western countries, which has generated and exacerbated scenarios of inequality throughout the world. According to Brown (2019), the neoliberal rationale that predominated in the last decades of the 20th century—cutting across multiple legal, social, political, and even cultural spheres—, served as a catalyst for acute developments of social inequality based on racial, colonial, sexual, and other criteria. In the same line of reasoning, Bigo (2002) states that the securitization of migration is based on a political-symbolic approach installed in specific territories subjected to the outcomes of the neoliberal management model: a structural discouragement shaped by personalized narratives in which freedom confronts anything that threatens its scope and, therefore, anything that is perceived as a risk to security: everything that is not from here, the unknown, the foreign and unfamiliar.

According to the Copenhagen School, securitization can be understood as an Austinian speech act. This means that the discourse of security should not be seen as separate from practice, as when something is discursively framed as a security issue, there is a parallel process of acting accordingly, especially if the contextual conditions are conducive to such action (Buzan et al., 1998; Vigneau, 2019). From this perspective, by naming a specific situation or dynamic as a security risk, it becomes insecure in practice, particularly when there is synchrony between the political ideology and the context in which this discourse unfolds. This approach provides analytical tools to consider how the implementation of Title 42 helped construct the perception of migrants as a threat to U.S. national security in the context of a pandemic. This has had direct consequences in strengthening border security and the biopolitical management of contemporary migration.

According to Buzan et al. (1998), prominent theorists of securitization, three characteristics of security can be identified: 1) the identification of a risk, 2) the sense of urgency to address it, and 3) the imperative of exceptional measures to confront the risk and threat. Securitization, in a political sense, operates through a perpetual and parallel framework of public actions, cultural narratives, social practices, and contextual elements—which, of course, do not unfold linearly and can be analyzed through various phases of reaffirmation, intensification, or relaxation— (Bourbeau, 2011). Additionally, securitization is also a relational process, according to a sociological conception (Balzacq, 2011; Vigneau, 2019), which means that the declaration of a threat, risk, or insecurity of an object is not inherent, universal, given, or immutable, but rather, as a relational process, it is elaborated through the interaction of various positions of power.

Securitization can be understood, then, as an

intersubjective process, whether intentional or not, through which an object is constituted as a security issue, through the combined effect of discourse, practices, and context, requiring the immediate use of defense or control mechanisms (Vigneau, 2019).

Consequently, the securitization of national borders refers to the interactive process through which certain external factors, such as migration or viral diseases—but also terrorism or drug trafficking—are constructed as a threat to the security of a country and its political and productive system, which activates processes of structural reinforcement of the border apparatus.

The history of the tightening and securitization of the borders between Mexico and the United States can be read in that sense, as it allows us to analyze the structural, social, and political processes that reinforced them,6 while also observing how the enemies, risks, or external threats that had to be combated or excluded from the territory were constructed in parallel: terrorists, drug traffickers, undocumented migrants, emerging infectious diseases, and so on (Del Monte Madrigal, 2021).

Of course, all these processes and strategies by the United States, as demonstrated by Leo Chavez (2013), have been underpinned by a narrative of the Latino threat that has been promoted in the public sphere throughout different stages. These discursive formations have constructed the image of migrants as illegal foreigners who refuse to integrate into the nation by maintaining their language and cultural practices even while on U.S. soil, making them perceived as an invading force.7 As can be observed, the reinforcement of borders is a nexus of political and discursive actions in constant flux, constructing its security based on the rejection of the foreign as dangerous.

Mbembe (2019) argues that one of the major contradictions of the liberal order is the tension between freedom and security. A society that prioritizes its security seeks to dissolve all uncertainties that would jeopardize its assumed freedom. Therefore, newcomers must be examined with the aim of exterminating any potential risk. This leads us to think, along with the Cameroonian philosopher, that “the objective of a securitarian society is not to affirm freedom but to control and govern modes of arrival” (Mbembe, p. 12). The proliferation of technologies to reinforce borders, as well as the normative provisions used for this purpose, such as Title 42, collaboratively contribute discursively, performatively, and practically to the reclassification of migrants into desirable or undesirable categories. Consequently, they establish themselves as biopolitical devices that construct external threats, leaving populations seeking international protection adrift in scenarios of terror and violence.

Necrosecuritization refers to the process in which the death of certain individuals—particularly racialized people—is promoted as a means to secure the lives of others (García Flores, 2021). In its conceptual development, necrosecurity is the counterpart of biosecurity, which focuses on ensuring life against biological threats by blurring the line between public health priorities and those of the armed forces. On the contrary, necrosecuritization implies the promotion of death to preempt other deaths; it aims to secure the lives of socially valued populations through a kind of counterfire involving the exposure to harm of expendable populations. In this sense, certain deaths signify better health for socially deemed deserving and normatively majority groups (Lincoln, 2021).

Although this concept could be seen as a conceptual derivation from the three axes mentioned earlier, it seems to me that the logic that instrumentalizes death—necrosecurity—does not fully align with the dynamics of Title 42. The fact that populations from the South are exposed to life- threatening risks through their expulsion is done under the pretext of safeguarding against the alleged biological threat, but it is ultimately driven by a political calculation to reinforce migratory control in times of pandemic exceptionalism. In any case, this policy can be considered on the threshold of both biosecurity and necrosecurity logics, as it adopts a war-like language and seeks to contain biological threats within the realm of political calculation, while also expelling populations to places where they are more vulnerable and thus exposed to greater threats, including death.

Consequences of Title 42 on Mobile Populations

One of the corollaries of the biosecuritarian and necrosecuritarian actions resulting from the expulsions authorized by Title 42 is related to the increased vulnerability of asylum seekers to risks associated with violence and criminality in Mexico. Despite documented evidence that the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) have left international protection seekers stranded at the border in a situation of vulnerability and hopelessness (Miranda & Silva Hernández, 2022), the organization Human Rights First (2021) reported, as of August 2021, more than 6 300 violent attacks against asylum seekers or individuals returned to Mexico under Title 42. This data is significant as it represents a four-fold increase in attacks compared to those reported during the years of MPP implementation.

In addition to these aggressions, migrants are unable to rely on the protection of security institutions. A migrant who returned to Mexico in February 2022 reported that as soon as they entered Mexico, they were approached and mistreated by the municipal police: “They turned me upside down (...), stole my money, and hit my knees and hands. I’m in pain, they threw me to the ground” (Humanizando la Deportación, 2022). Instead of providing certainty and protection, law enforcement agents have come to be perceived as a source of risk and violence by the migrants themselves.

On the other hand, the WOLA organization (Isacson, 2023) documented how in the last three months of 2022 and the first of 2023, migrant shelters in the city of Tijuana experienced an alarming increase in attacks, threats, and hostilities that not only endanger the security of the migrants trapped at the border (many of them as a result of expedited expulsions under Title 42), but also make them vulnerable to organized crime.

The implementation of Title 42 has also meant returning forcibly displaced individuals to dangerous contexts precisely because of the violence in their countries of origin, as described by Zoila, who, coming from Honduras, fled from Ojinaga to reach Tijuana, where she was mistreated again upon being returned to Mexico under Title 42.

In Ojinaga, they tried to kidnap my baby (...) they told me they were angry with me because a mother doesn’t abandon her children, even though I was pregnant. They didn’t kill me because they said they don’t kill in front of children (...) that’s why I came here to Tijuana (...) when we arrived, we were living in El Chaparral, but there I was assaulted and had my identification stolen. A woman told me to come to this shelter (Zoila, personal communication, July 2021).8

This testimony reinforces the fact that Title 42 has been a biopolitical and necropolitical mechanism for migration management. However, perhaps the case of Kenia best exemplifies the danger of staying or being returned to the Mexican side, as she has experienced aggression from both criminal groups and police officers.

I left Honduras due to extortion (...) they gave us two days to pay the fee (...) it was an organization over there, Maras and gangs (...) [during the journey] the problems started in Veracruz. We were waiting for a bus when some people arrived and grabbed us, blindfolded us (...) we were there for eight days (...) when we got out and were on the bus, we were grabbed again. We were apprehended by the federal police. I thought we were being deported. It was practically a kidnapping because they kept us for two days in the middle of the forest, enduring cold and sun (...) until my cousin sent them money (...) [after attempting to cross into the United States] We didn’t even know why we were expelled until my husband asked, “you were expelled under Title 42”. There at the border crossing, they gave us food and issued us a paper to move around here, a permit, they put us on a bus, and we arrived here (Kenia, personal communication, July 2021).

In the testimonies of individuals who were returned to Mexico under Title 42, it is evident that a consistent experience is confronting a wide spectrum of violence—from criminal groups, authorities, certain social sectors, and even within their own families—which they have had to navigate either in their places of expulsion or during their transit through Mexico. To a large extent, it is this violence that has compelled these individuals to undertake the migratory journey in search of international protection, and yet they are being returned and placed in a highly vulnerable situation.

As can be seen, Title 42 was established as a mechanism that exacerbated precarity and placed populations fleeing violence and terror at high risk of fatal consequences. In this regard, Human Rights Watch (HRW) provided insights into understanding the underlying motives behind the implementation of this order when it described Title 42 as “the most egregious example of how public health authorities have misused their authority to help create discriminatory migration policies” (Human Rights Watch, 2021).

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The implementation of Title 42 clearly targeted a specific group: those who sought to enter the United States without documentation, without even considering whether they were international protection seekers. Not every person presenting themselves at the country’s ports of entry would be expelled under this mandate, as American citizens or foreign nationals with valid visas were exempted from this directive. In this sense, Title 42 only deemed those entering without documentation—such as asylum seekers—as a public health threat, disregarding scientific evidence and reasonable political judgment regarding pandemic containment measures. This policy singled out these individuals as the sole vectors of SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

By expelling them, the policy individualized the responsibility of containing the virus transmission to the migrants themselves, a task that should have been taken up by a State respectful of basic human rights concerning international protection and non-refoulement. The United States prioritized self-containment over establishing proper migration processing mechanisms and asylum application procedures that would prevent virus transmission.

Stated in this way, it is not that migrants themselves pose a danger to Northern nations, but rather that a system constructs them as a threat based on global biopolitical and necropolitical migration processing systems, and in an epidemiological surveillance regime that has subsumed health under the logic of security. Therefore, border directives during times of pandemic, such as those established in Title 42, have helped clearly delineate what represents a risk for the United States. This has had a severe impact by further precariousizing the vulnerable lives of asylum seekers and, therefore, has served to reinforce the practice and discourse of what the United States must safeguard itself from.

However, the implementation of Title 42 was inconsistent with a transborder health policy, as while land crossing was prohibited for all essential travelers, the border remained open for American citizens, and air and sea arrivals were not banned for foreigners. This restriction on entry to the country, based on arguments of health protection, points to a political management of migration control rather than protection against health risks. In this sense, Title 42 has been a biopolitical and necropolitical implementation serving not sanitary immunization, but migratory immunization, which has expelled vulnerable individuals to violent territories where their lives are still at risk.

REFERENCES

Aldis, W. (2008). Health security as a public health concept: A critical analysis. Health Policy and Planning, 23(6), 369-375. [ Links ]

American Immigration Council [AIC]. (2021). A guide to Title 42 expulsions at the border. AIC. [ Links ]

Balzacq, T. (Ed.). (2011). Securitization theory. How security problems emerge and dissolve. Routledge. [ Links ]

Basile, G. (2020a). La triada de cuarentenas, neohigienismo y securitización en el SARS-CoV-2: matriz genética de la doctrina del panamericanismo sanitario. IDEP-FLACSO. [ Links ]

Basile, G. (2020b). SARS-CoV-2 en América Latina y el Caribe: Las tres encrucijadas para el pensamiento crítico en salud. Ciencia e Saude Colectiva, 25(9), 3557-3562. [ Links ]

Bigo, D. (2002). Security and immigration: Toward a critique of the governmentality of unease. Alternatives, 27 (1), 63-92. [ Links ]

Bourbeau, P. (2011). The securitization of migration: A study of movement and order. Routledge. [ Links ]

Breilh, J. (2010). Las tres “S” de la determinación de la vida: 10 tesis hacia una visión crítica de la determinación social de la vida y la salud. En R. Passos, Determinaçao Social de Saúde e Reforma Sanitária (pp. 87-125). Centro Brasileiro de Estudos de Saúde. [ Links ]

Brown, W. (2019). In the ruins of neoliberalism. The rise of antidemocratic politics in the West. Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Buzan B., Weaver O. y De Wilde J. (1998). Security: A new framework for analysis. Lynne Rienner Publishers. [ Links ]

Cartwright, T. (2022). ICE Air Flights January 2022 & Last 12 Months. Witness at the border. https://witnessattheborder.org/posts/21322 [ Links ]

Casas-Cortes, M., Covarrubias, S., De Genova, N. y Tienda, G. (2014). New keywords: Migration and borders. Cultural Studies, 29(1), 55-87. [ Links ]

Castro Franco, A. (2016). La gobernanza internacional de las migraciones: de la gestión migratoria a la protección de los migrantes. Universidad Externado de Colombia. [ Links ]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (16 de octubre de 2020). Order suspending introduction of persons from countries where a quarantinable communicable disease exists, Federal Register, 85(201), pp. 65806-65812. [ Links ]

Chavez, L. (2013). The Latino threat: Constructing immigrants, Latinos, and the nation. Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Columbia Public Health. (2020). Public health experts urge U.S. officials to withdraw order enabling mass expulsion of asylum seekers. Columbia University Irving Medical Center. https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/public-health-now/news/public-health-experts-urge-us-officials-withdraw-order-enabling-mass-expulsion-asylum-seekers [ Links ]

Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos [CIDH]. (2015). Derechos humanos de migrantes, refugiados, apátridas, víctimas de trata de personas y desplazados internos: normas y estándares del Sistema Interamericano de Derechos Humanos (OEA/Ser.L/V/II). CIDH/OEA. http://www.oas.org/es/cidh/informes/pdfs/movilidadhumana.pdf [ Links ]

Davis, S. E. (2008). Securitizing infectious disease. International Affairs, 84(2), 295-313. Dearen, J. y Burke, G. (2020). Pence ordered borders closed after CDC experts refused. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/virus-outbreak-pandemics-public-health-new-york-health-4ef0c6c5263815a26f8aa17f6ea490ae [ Links ]

De la Flor, J. L. (2018). La seguridad sanitaria global a debate. Lecciones críticas aprendidas de la 24ª EVE. Comillas Journal of International Relations, (13), 49-62. [ Links ]

Dearen, J. y Burke, G. . 2020. . Pence ordered borders closed after CDC experts refused. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/virus-outbreak-pandemics-public-health-new-york-health-4ef0c6c5263815a26f8aa17f6ea490ae [ Links ]

Del Monte Madrigal, J. A. (2021). La securitización de la frontera México-Estados Unidos en tiempos pre y pospandémicos. Nómadas, (54), 83-99. [ Links ]

Del Monte Madrigal, J. A. (2022). El Título 42. Dos años de una política sanitaria al servicio del control migratorio . Observatorio de Legislación y Política Migratoria/El Colegio de la Frontera Norte. http://observatoriocolef.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/PDF-Reporte_smallsize-v3.pdf [ Links ]

Dickerson, C. y Shear, M. D. (3 de mayo de 2020). Before COVID-19, Trump aide sought to use disease to close borders. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/03/us/coronavirus-immigration-stephen-miller-public-health.html [ Links ]

Domenech, E. (2017). Las políticas de migración en Sudamérica: elementos para el análisis crítico del control migratorio y fronterizo. Terceiro Milenio. Revista Crítica de Sociología e Política, 8(1), 19-48. [ Links ]

Esposito, R. (2006). Bíos: biopolítica y filosofía. Amorrortu Editores. [ Links ]

Estévez, A. (2020). Biopolítica y necropolítica ¿constitutivos u opuestos? En A. Varela Huerta, A., Necropolítica y migración en la frontera vertical mexicana. Un ejercicio de conocimiento situado (pp. 13-45). IIJ/UNAM. [ Links ]

Garcia Flores, B. G. (2021). The emergence of necrosecurity: On the extra-legality of the rule of law and the death of the willful subject. En A. Estévez, Necropower in North America: The legal spatialization of disposability and lucrative death (pp. 153-174). Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Geiger, M. y Pecoud, A. (2010). The politics of international migration management. Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Ghosh, B. (Ed.) (2000). Managing migration: Time for a new international regime? Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Goodman, A. (2020). The deportation machine. America’s long history of expelling. Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Guttentag, L. (2020). Coronavirus border expulsions: CDC’s assault on asylum seekers and unaccompanied minors. Just Security, 13. https://www.justsecurity.org/69640/coronavirus-border-expulsions-cdcs-assault-on-asylum-seekers-and-unaccompanied-minors/ [ Links ]

Human Rights First. (2021). Human rights travesty: Biden administration embrace of trump asylum expulsion policy endangers lives, wreaks havoc. Autor. https://humanrightsfirst.org/library/human-rights-travesty-biden-administration-embrace-of-trump-asylum-expulsion-policy-endangers-lives-wreaks-havoc/ [ Links ]

Human Rights Watch. (2021). Q&A: US Title 42 Policy to Expel Migrants at the Border. Autor. https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/04/08/qa-us-title-42-policy-expel-migrants-border [ Links ]

Humanizando la Deportación. (2022). En mi país no puedo ser libre [Video]. Autor. http://humanizandoladeportacion.ucdavis.edu/es/2022/08/22/329-en-mi-pais-no-puedo-ser-libre/ [ Links ]

Isacson, A. (2023). Los ataques contra los albergues para migrantes en Tijuana crecen, mientras EE. UU. devuelve a cientos de migrantes al día. Washington Office on Latin America [WOLA]. https://www.wola.org/es/analisis/los-ataques-contra-los-albergues-para-migrantes-en-tijuana-crecen-mientras-ee-uu-devuelve-a-cientos-de-migrantes-al-dia/ [ Links ]

King, N. B. (2002). Security, disease, commerce: Ideologies of postcolonial global health. Social Studies of Science, 32(5-6), 763-789. [ Links ]

Kraut, A. M. (1994). Silent travelers: Germes, genes and the immigrant menace. John Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

Lincoln, M. (2021). Necrosecurity, immunosupremacy, and survivorship in the political imagination of COVID-19. Open Anthropological Research, 1(1), 46-59. [ Links ]

Lind, D. (2020, 2 de abril). Leaked border patrol memo tells agents to send migrants back immediately—ignoring Asylum Law. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/leaked-border-patrol-memo-tells-agents-to-send-migrants-back-immediately-ignoring-asylum-law [ Links ]

Mármora, L. (2002). Las políticas de migraciones internacionales. Paidós. [ Links ]

Mbembe, A. (2011). Necropolítica. Melusina [ Links ]

Mbembe, A. (2019). Bodies as borders. From the European South, (4), 5-18. [ Links ]

Mezzadra, S. (2005). Derecho de fuga. Migraciones, ciudadanía y globalización. Tinta Limón/Traficantes de sueños. [ Links ]

Miranda, B. y Silva Hernández, A. (2022). Gestión desbordada: solicitudes de asilo en Estados Unidos y los mecanismos de espera allende en sus fronteras. Migraciones Internacionales, 13(4). https://doi.org/10.33679/rmi.v1i1.2385 [ Links ]

OMS [Organización Mundial de la Salud]. (2007). Informe sobre la salud en el mundo 2007. Protección de la salud pública mundial en el siglo XXI: un porvenir más seguro. Autor. [ Links ]

Ortega, E. (2022). El asilo como derecho en disputa en México. La raza y la clase como dispositivos de exclusión. IIJ/ UNAM. [ Links ]

Overbeek, H. (2002). Neoliberalism and regulation of global labor mobility. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 581(1), 74-90. [ Links ]

Parrini, R. (2015). Biopolíticas del abandono: migración y dispositivos médicos en la frontera sur de México. Nómadas, (42), 111-127. [ Links ]

Shah, N. (2001). Contagious divides: Epidemics and race in San Francisco’s Chinatown. University of California Press. [ Links ]

U. S. Code Título 42. The Public Health and Welfare de 1944. Capítulo 6A, Subcapítulo II, Parte G § 265. 1 de julio de 1944. (Estados Unidos). https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/265 [ Links ]

U. S. Custom and Border Protection. (2020). Nationwide Enforcement Encounters: Title 8 Enforcement Actions and Title 42 Expulsions Fiscal Year 2020. Department of Homeland Security. https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/cbp-enforcement-statistics/title-8-and-title-42-statistics-fy2020 [ Links ]

U. S. Custom and Border Protection. (2021). Nationwide Enforcement Encounters: Title 8 Enforcement Actions and Title 42 Expulsions Fiscal Year 2021. Department of Homeland Security. https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/cbp-enforcement-statistics/title-8-and-title-42-statistics-fy2021 [ Links ]

U. S. Custom and Border Protection. (2022). Nationwide Enforcement Encounters: Title 8 Enforcement Actions and Title 42 Expulsions Fiscal Year 2022. Department of Homeland Security. https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/cbp-enforcement-statistics/title-8-and-title-42-statistics-fy22 [ Links ]

Vanderhook, K. (2002). Origins of federal quarantine and inspection laws. https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/8852098/vanderhook2.html [ Links ]

Varela Huerta, A. (2020). Necropolítica y migración en la frontera vertical mexicana. Un ejercicio de conocimiento situado. IIJ/UNAM. [ Links ]

Vigneau, E. (2019). Securitization theory and the relationship between discourse and context: A study of securitized migration in the Canadian press, 1998-2015. Revue européenne des migrations internationals, 1(2), 191-214. [ Links ]

2The testimonies used in this article come from two research projects related to the effects on migrants of both COVID-19 and the implementation of restrictive policies in contexts of pandemic exceptionalism. The first collected testimonies from women at the Centro Integrador para el Migrante “Carmen Serdán” in Tijuana, and the second developed digital stories as part of the “Migrants and COVID-19 in Tijuana: Digital Stories” project, which is part of the broader proyect entitled “Humanizando la deportación”.

3According to Cartwright (2022), 413 of these flights were carried out between March and December 2021. The organization Witness at the Border has also documented expulsions under Title 42 through flights destined for southern Mexico, countries in the southern hemisphere, or the Caribbean.

4The dispute has continued at the time of writing, but despite this, migrants are still being expelled, and in October 2022, this regulation was invoked to expel a significant number of Venezuelan migrants who were seeking international protection as part of a political exchange between Mexico and the United States regarding immigration matters. Despite there being deadlines to end this provision, the judicial impasse and the Biden administration itself have indicated that Title 42 will continue to govern informal crossings as long as the COVID-19 emergency declaration remains in effect.

5As evidence of this, both in Mexico and in several countries in Latin America, it was the military forces who guarded and distributed the COVID-19 vaccines during this pandemic.

6Such as World War II, the Bracero Program, the amnesty of the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), prevention programs through deterrence, the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA), the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA), the September 11 attacks, the Homeland Security Act (which integrated the fight against migration, terrorism, and drug trafficking), the Secure Communities program, the Consequence Delivery System, the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), the administrative “walls” of the Trump administration, the COVID-19 pandemic, among others.

7In this public discourse, it has been the media that has significantly influenced the construction of what is considered foreign, illegitimate, illegal, or foreigner.

Received: November 07, 2022; Accepted: March 18, 2023

text in

text in