Phytopathological notes

In vitro nematocidal activity of the Pleurotus djamor PdR-2 fraction against J2 of Meloidogyne enterolobii

Olga Gómez-Rodríguez1

Jesús Antonio Pineda-Alegría2

Gloría Sarahi Castañeda-Ramírez2

Manasés González-Cortazar3

José E. Sánchez4

Liliana Aguilar-Marcelino2

*

1 Fitopatología, Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus Montecillo, Km. 36.5 Carretera México-Texcoco, C.P. 56230, Texcoco, Estado de México, México;

2 Unidad de Helmintología, CENID-Salud Animal e Inocuidad, INIFAP, Carretera Federal Cuernavaca-Cuautla. No. 8534, C. P. 62550, Jiutepec, Morelos, México;

3 Centro de Investigación Biomédica del Sur, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social. Argentina No. 1. Col. Centro. C.P. 62790, Xochitepec, Morelos, México;

4 El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, carretera al Antiguo Aeropuerto km. 2.5 C.P. 30700, Tapachula, Chiapas, México;

Abstract.

Recently, the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne enterolobii have generated important economic losses (65%) in worldwide agriculture. In the present study, the nematocidal activity of the PdR-2 fraction of Pleurotus djamor was evaluated against the second instar juvenile (J2) of M. enterolobii. Different concentrations of the PdR-2 fraction (0.039, 0.078, 0.156, 0.132, 0.625, and 1.25 mg mL-1) were evaluated, as well as the respective control groups (water and Levamisole, 5 mg mL-1) in a volume of 100 µL (n=4). J2s were exposed for 24 h and subsequently quantified, and the percentage of mortality was estimated. Data were analyzed by analysis of variance with the general linear model and a comparison of means with Tukey’s test (p < 0.05). The PdR-2 fraction at concentrations of 0.132, 0.625, and 1.25 mg mL-1 were significantly equal with respect to Levamisole application, showing a mortality of 87.6, 84.5, and 86.3%, respectively. At the lowest concentration (0.039 mg mL-1), 40.3% mortality was recorded, whereas 86% was recorded at the highest concentration evaluated (1.25 mg mL-1). The PdR-2 fraction of P. djamor had nematocidal activity against J2s of M. enterolobii.

Key words: root-knot nematode; Edible mushroom; Chemical fraction; Alternative control

Resumen.

Recientemente, el nematodo agallador Meloidogyne enterolobii ha generado importantes pérdidas económicas (65%) en la agricultura a nivel mundial. En el presente estudio se evaluó la actividad nematicida de la fracción PdR-2 de Pleurotus djamor contra juveniles del segundo estadio (J2) de M. enterolobii. Se evaluaron diferentes concentraciones de la fracción PdR-2 (0.039, 0.078, 0.156, 0.132, 0.625 y 1.25 mg mL-1), así como los respectivos grupos de control (agua y Levamisol, 5 mg mL-1) en un volumen de 100 µL (n=4). Los J2 fueron expuestos durante 24 h y posteriormente cuantificados, y se estimó el porcentaje de mortalidad. Los datos se analizaron mediante un análisis de varianza y una comparación de medias con la prueba de Tukey (p<0,05). La fracción PdR-2 a concentraciones de 0.132, 0.625 y 1.25 mg mL-1 fue significativamente igual con respecto a la aplicación de Levamisol, con una mortalidad de 87.6, 84.5 y 86.3%, respectivamente. En la concentración más baja (0.039 mg mL-1) se registró una mortalidad del 40.3%, mientras que en la concentración más alta (1.25 mg mL-1) se registró un 86%. La fracción PdR-2 de P. djamor tuvo actividad nematicida contra los J2 de M. enterolobii.

Palabras clave: Nematodo agallador; hongo comestible; fracción química; alternativa de control

Plant-parasitic nematodes of the genus Meloidogyne cause significant economic losses worldwide (Abd-Elgawad and Askary, 2015). One hundred species of the genus Meloidogyne that parasitize vascular plants have been described (Moens et al., 2009). M. incognita is one of the most widely distributed species, followed by M. javanica, M. arenaria, and M. hapla (Carrillo-Fasio et al., 2019).

However, M. enterolobii (= M. mayaguensis) has become one of the most important species worldwide in recent decades because of its high aggressiveness (Castagnone-Sereno, 2012), its reproductive potential, wide geographic distribution, large host range, including both herbaceous and woody plants, and its ability to establish on plants carrying resistance genes to other Meloidogyne spp., such as some genotypes of tomato (Mi-1), potato (Mh), soybean (Mir1), and chili bell pepper (N and Tabasco) (Castagnone-Sereno, 2012). M. enterolobii has been reported in Africa, Europe, the United States of America, Central America, and South America (Castagnone-Sereno, 2012; Moens et al., 2009). Recently, in Mexico, it was reported parasitizing watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) in the state of Veracruz and chilli (Capsicum annuum) in Sinaloa (Ramirez-Suarez et al., 2014; Villar-Luna et al., 2016). In the states of Sinaloa and Baja California Sur, M. enterolobii is more prevalent than M. incognita (Carrillo-Fasio et al., 2019; Romero et al., 2019).

Management of Meloidogyne spp. has focused mainly on chemical control, soil biofumigation, amendments, and resistant varieties (Cid del Prado-Vera et al., 2018). However, these control methods have not been sufficient for M. enterolobii given the intrinsic characteristics of its biology. Therefore, it is important to continue searching for other management alternatives for this nematode species. One of the alternatives is the use of nematocidal compounds found in the environment (Akhtar and Malik, 2000). On the other hand, one of the sustainable alternatives is the use of endophytic bacteria such as Serratia ureilytica, which has been evaluated in vitro against Nacobbus aberrans (J2) and in infected chilli plants, obtaining encouraging results (Wong et al., 2021).

These types of compounds with nematocidal activity have been reported in mushrooms of the genus Pleurotus (Barron and Thorn, 1987), in addition to having the ability to colonize and degrade a great variety of lignocellulosic residues and high medicinal and nutritional value (Cohen et al., 2002). A toxin was identified in this genus of fungi as trans-2-decenedioic acid, with a nematocidal effect against Panagrellus redivivus (Kwok et al., 1992). There have also been studies with activity against phytoparasites (Castañeda-Ramírez et al., 2020). Furthermore, Heydari et al. (2006) reported the presence of a toxin in five Pleurotus spp. in water agar with an effect against M. javanica (J2). Likewise, the proteolytic activity of P. ostreatus is reported on the free-living nematode Panagrellus sp. (Genier et al., 2015).

Additionally, it has been attributed to antiparasitic properties, mainly cestocidal (Samsam-Shariat et al., 1994) and nematocidal in the livestock area (Pineda-Alegría et al., 2017); however, in the agricultural area, it is important to conduct studies that contribute to the development of natural bionematicides based on edible fungi. The PdR-2 fraction of the edible mushroom P. djamor has been previously reported with nematocidal activity on infective larvae (L3) of Haemonchus contortus in vitro studies (González-Cortazar et al., 2020). For this reason, the nematocidal activity of the PdR-2 fraction of P. djamor against J2s of M. enterolobii was evaluated in the present study.

The present study was carried out at the Helminthology Laboratory of the National Center for Disciplinary Research in Animal Health and Safety (CENID-SAI) of the National Institute of Forestry, Agriculture, and Livestock Research (INIFAP), located in Jiutepec, Morelos, Mexico. J2 were obtained from the root-knot of tomato cv. ‘Rio Grande’ (monoxenic crop, population of Ahome, Sinaloa) at the Postgraduate College, Montecillo Campus, Texcoco. Eggs were extracted according to the methodology of Vrain (1977) and incubated at 28±1 °C in Petri dishes with sterile distilled water to obtain J2.

Obtaining the PdR-2 fraction of P. djamor.

The PdR-2 fraction was obtained from the hydroalcoholic extract (ethanol-water 7:3) of P. djamor strain ECS-0127 basidiomata. The extract (30 g) was adsorbed on 40 g of normal phase silica gel (70-230 mesh, Merck) and placed on a pre-packed glass chromatographic column. The elution system was performed with dichloromethane:methanol with the following system changes: 100, 90:10, 70:30, 50:50, and 100%. Samples were collected and concentrated in a rotary evaporator. The fractions were analyzed by thin layer chromatography and pooled according to their retention factor and elution system. From this fractionation, 22 fractions were obtained, of which fractions 11 to 18 formed the PdR-2 fraction (González-Cortazar et al., 2020).

In vitro evaluation of the PdR-2 fraction of P. djamor against J2 of M. enterolobii.

Different concentrations of the PdR-2 fraction and 100 J2 specimens of M. enterolobii were placed in a 96-well plate. The final concentrations of the fraction were 0.039, 0.078, 0.156, 0.132, 0.625, and 1.25 mg mL-1 and controls, which were distilled water and Levamisole (commercial anthelmintic) 5 mg mL-1 in a volume of 100 µL (n=4). The J2 were exposed for 24 h, and after the exposure time, 10 aliquots of 10 µL were taken from each repetition, and the number of dead and alive individuals were counted. The number of dead individuals was used to calculate the percentage of mortality using the following formula:

larval mortality=dead nematodesdead nematodes+ live nematodes×100

Data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the general linear model and a comparison of means with Tukey’s test (*p ≤ 0.05). STATGRAPHICS Centurion XV, V. 15.2.06 software was used for statistical procedures.

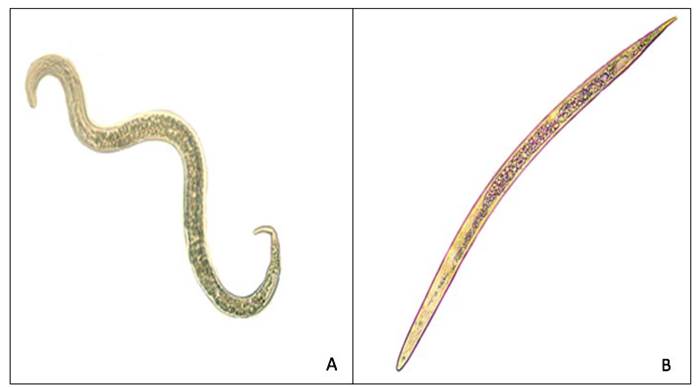

The mortality of M. enterolobii J2 is presented in Table 1. No dead individuals were recorded when distilled water was used, and the J2 presented movement as shown in Figure 1A; however, with the anthelmintic (Levamisole), 100% mortality was recorded at 24 h of exposure (Figure 1B) with statistically significant differences (*p ≤ 0. 05) with respect to the lowest concentrations of the PdR-2 fraction (0.039, 0.078, and 0.156 mg mL-1) and water. The mortality for the lowest concentrations were 40.3 to 65%. On the other hand, concentrations of 0.156, 0.132, 0.625, and 1.25 mg mL-1 of the PdR-2 fraction showed higher mortality percentages (76.8-86.3%), and these were significantly different from the water control (*P≤ 0.05).

Table 1 Mortality of J2 of Meloidogyne enterolobii caused by the Pleurotus djamor PdR-2 fraction at 24 h after exposure.

| Treatment |

Concentration (mg mL-1) |

Mortality percentage (%)y,z

|

| H2O |

- |

0±0 a

|

| Levamisole |

5 |

100±0 e

|

| PdR2 Fraction |

0.039 |

40.3±5.6 b

|

| 0.078 |

65.1±5.9 c

|

| 0.156 |

76.9±7.1 cd

|

| 0.132 |

87.6±3.7 de

|

| 0.625 |

84.6±4.7 de

|

| 1.25 |

86.3±10.5 de

|

y Data represent the mean ± standard deviation of four replicates.

z The same letters in a column indicate that the value does not differ statistically, according to Tukey’s test (*P≤ 0.05); n = 4.

Currently, research carried out for the control of M. enterolobii has focused on the search for crops resistant to this phytonematode, given that this species is able to reproduce in different crops that possess the resistance genes currently available for the main species of Meloidogyne. Some of these genes are Me1-Me6, Mech1 and Mech2; however, it has been reported that M. enterolobii can infect plants with these Meloidogyne-resistant genes (Carrillo-Fasio et al., 2020; Philbrick et al., 2020). Therefore, another sustainable alternative for the control of this nematode could be the use of compounds isolated from edible mushrooms.

Several species of edible mushrooms belonging to the genus Pleurotus have been shown to possess nematocidal properties; such studies have been conducted mainly in the livestock area using gastrointestinal nematode models of small ruminants, reporting a new line of research to be addressed to demonstrate their effectiveness in the sustainable control of these parasites (Castañeda-Ramírez et al., 2020). The nematocidal activity is attributed to secondary metabolites, such as fatty acids, isolated from P. djamor species (e.g., linoleic acid) (Pineda-Alegría et al., 2017). Other secondary metabolites, such as polyols, trehalose, mannitol, squalene, stearic acid, and β-sitosterol, have been isolated from P. eryngii (Cruz-Arévalo et al., 2020). Regarding the PdR-2 fraction obtained from P. djamor (ECS-0127) was reported in a study by González-Cortázar et al. (2020), 100% lethal nematocidal activity was reported against eggs and infective larvae (L3) of H. contortus in in vitro experiments. Similarly, in vivo evaluation of the PdR-2 fraction reached a reduction of up to 80% of the H. contortus parasite load using as a study model the gerbil Meriones unguiculatus. Finally, the compound responsible for the nematocidal activity of the PdR-2 fraction was identified as allitol and a terpene in a 9:1 ratio by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) proton (1H) and carbon (13C) spectroscopic analysis.

Most of the research works where the use of Pleurotus mushroom metabolites has been explored are focused on Meloidogyne spp., such as M. javanica (Heydari et al., 2006; Oka, 2001); however, for the recently reported species in Mexico, M. enterolobii, research for its management is required. Therefore, our research provides relevant information. At a concentration of 0.132 mg mL-1, mortality percentages higher than 84% were obtained on J2s of M. enterolobii. Similar results were reported by Li et al. (2007), who isolated three metabolites from P. ferulae extracts with a nematocidal effect on Bursaphelenchus xylophilus and Panagrellus redivivus. Of these, only the compound cheimonophyllon E registered 84% mortality on B. xylophilus at 72 h, while the PdR-2 fraction evaluated in this work registered a similar percentage at 24 h. Therefore, The PdR2 fraction showed nematocidal effect against J2s larvae of M. enterolobii and could potentially be used for the sustainable control of nematodes of agricultural importance.

Acknowledgments

The present research article was partial financed by the National Problems project, National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT in Spanish), project number 9342634372.

Literature cited

Abd-Elgawad MMM and Askary TH. 2015. Impact of phytonematodes on agriculture economy. pp. 3-49. In: Askary TH and Martinelli PRP (Eds.). Biocontrol agents of phytonematodes. Wallingford, UK: CABI. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781780643755.0003.

[ Links ]

Akhtar M and Malik A. 2000. Roles of organic soil amendments and soil organisms in the biological control of plant-parasitic nematodes: a review. Bioresource Technology 74:35-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-8524(99)00154-6

[ Links ]

Barron GL and Thorn RG. 1987. Destruction of nematodes by species of Pleurotus. Canadian Journal of Botany 65:774-778. https://doi.org/10.1139/b87-103

[ Links ]

Carrillo-Fasio JA, Martínez-Gallardo JA, Allende-Molar R, Velarde-Félix S, Romero-Higareda CE and Retes-Manjarrez JE. 2019. Distribution of Meloidogyne species (Tylenchida: Meloidogynidae) in tomato crop in Sinaloa, Mexico. Nematropica 49:71-82. https://journals.flvc.org/nematropica/article/view/115619

[ Links ]

Carrillo-Fasio JA, Martínez-Gallardo JA, Ayala-Tafoya F, López-Orona CA, Allende-Molar R and Retes-Manjarrez JE. 2020. Screening for resistance to Meloidogyne enterolobii in Capsicum annuum landraces from Mexico. Plant Disease 104(3): 817-822. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-04-19-0718-RE

[ Links ]

Castagnone-Sereno P. 2012. Meloidogyne enterolobii (=M. mayaguensis): profile of an emerging, highly pathogenic, root-knot nematode species. Nematology 14: 133-138. https://doi.org/10.1163/156854111X601650

[ Links ]

Castañeda-Ramírez GS, Torres-Acosta JFJ, Sánchez JE, Mendoza de Gives P, González-Cortazar M, Zamilpa A, Al-Ani LKT, Sandoval-Castro C, Soares FEF and Aguilar-Marcelino L. 2020. Biotechnological use of edible mushrooms bio-products for controlling plant and animal parasitic nematodes. Biomed Research International 6078917: 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6078917

[ Links ]

Cid del Prado-Vera I, Franco-Navarro F and Godinez-Vidal D. 2018. Plant parasitic nematodes and management strategies of major crops in Mexico. pp. 31-68. In: Subbotin SA and Chitambar JJ (Eds.), Plant Parasitic Nematodes in Sustainable Agriculture of North America, sustainability in plant and crop protection. Switzerland: Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99585-4_2

[ Links ]

Cohen R, Persky L and Hadar Y. 2002. Biotechnological applications and potential of wood-degrading mushrooms of the genus Pleurotus. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 58(5): 582-94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-002-0930-y

[ Links ]

Cruz-Arévalo J, Sánchez JE, González-Cortázar M, Zamilpa A, Andrade-Gallegos RH, Mendoza de Gives P and Aguilar-Marcelino L. 2020. Chemical composition of an anthelmintic fraction of Pleurotus eryngii against eggs and infective Larvae (L3) of Haemonchus contortus. Biomed Research International 4138950: 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4138950

[ Links ]

Genier HLA, de Freitas SFE, de Queiroz JH, de Souza GA, Araújo JV, Braga FR, Pinheiro IR and Kasuya MCM. 2015. Activity of the fungus Pleurotus ostreatus and of its proteases on Panagrellus sp. larvae. African Journal of Biotechnology 14(17): 1496-1503. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB2015.14447

[ Links ]

González-Cortazar M, Sánchez JE, Huicochea-Medina M, Hernández-Velázquez VM, Mendoza-de-Gives P, Zamilpa A, López-Arellano ME, Pineda-Alegría JA and Aguilar-Marcelino L. 2020. In vitro and in vivo nematicide effect of Pleurotus djamor fruiting bodies against Haemonchus contortus. Journal of Medicinal Food 24(3): 310-318. https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2020.0054

[ Links ]

Heydari R, Pourjarn E and Mohammadi EG. 2006. Antagonistic effect of some species of Pleurotus on the root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne javanica in vitro. Plant Pathology Journal 5(2):v173-177. https://doi.org/10.3923/ppj.2006.173.177

[ Links ]

Kwok OCH, Plattner R, Weisleder D and Wichlow DT. 1992. A nematicidal toxin from Pleurotus ostreatus NRRL 3526. Journal Chemical Ecology 18: 127-136. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00993748

[ Links ]

Li G, Wang X, Lijun L, Li L, Huang R and Zhang K. 2007. Nematicidal metabolites from the fungus Pleurotus ferulae Lenzi. Annals of Microbiology 57(4):v527-529. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03175350

[ Links ]

Moens M, Perry RN and Starr JL. 2009. Meloidogyne Species - a diverse group of novel and important plant parasites. In: Perry RN, Moens M and Starr JL (Eds.). Root-knot nematodes (pp.1-17). Wallingford, UK: CAB International. https://www.cabi.org/isc/FullTextPDF/2009/20093330181.pdf

[ Links ]

Oka Y. 2001. Nematicidal activity of essential oil components against the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica. Nematology 3:159-164.

[ Links ]

Philbrick AN, Adhikari TB, Louws FJ and Gorny AM. 2020. Meloidogyne enterolobii, a major threat to tomato production: current status and future prospects for its management. Frontiers in Plant Science 11: 606395. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.606395

[ Links ]

Pineda-Alegría JA, Sánchez-Vázquez JE, González-Cortazar M, Zamilpa A, López-Arellano ME, Cuevas-Padilla EJ, Mendoza-de-Gives P and Aguilar-Marcelino L. 2017. The edible mushroom Pleurotus djamor produces metabolites with lethal activity against the parasitic nematode Haemonchus contortus. Journal of Medicinal Food 20: 1184-1192. https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2017.0031

[ Links ]

Ramirez-Suarez A, Rosas-Hernandez L, Alcasio-Rangel S and Powers TO. 2014. First report of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne enterolobii parasitizing watermelon from Veracruz, México. Plant Disease 98(3): 428. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-06-13-0636-PDN

[ Links ]

Romero M, Macías MG, Carrillo FJA, Rojas CM, Hernández RJS and Duarte OJD. 2019. Identificación y distribución de especies de Meloidogyne en Baja California Sur, México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas 10(2): 337-349. https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v10i2.1603

[ Links ]

Samsam-Shariat H, Farid H and Kavianpour M. 1994. A study of the anthelmintic activity of aqueous extract of Pleurotus eryngii on Syphacia obvelata and Hymenolepis nana. Journal of Science, Islamic Republic of Iran 5:19-22. https://jsciences.ut.ac.ir/article_31372.html

[ Links ]

Villar-Luna E, Gómez-Rodríguez O, Rojas-Martínez RI and Zavaleta-Mejía E. 2016. Presence of Meloidogyne enterolobii on jalapeño pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) in Sinaloa, Mexico. Helminthologia 53: 155-160. https://doi.org/10.1515/helmin-2016-0001

[ Links ]

Vrain TC. 1977. A technique for the collection of larvae of Meloidogyne spp. and a comparison of eggs and larvae as inocula. Journal of Nematology 9: 249-251. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2620246/

[ Links ]

Wong-Villarreal A, Méndez-Santiago EW, Gómez-Rodríguez O, Aguilar-Marcelino L, García DC, García-Maldonado JQ, Hernández-Velázquez VM, Yañez-Ocampo G, Espinosa-Zaragoza S, I Ramírez-González S, Sanzón-Gómez D. 2021. Nematicidal Activity of the EndophyteSerratia ureilyticaagainstNacobbus aberransin Chili Plants (Capsicum annuumL.) and Identification of Genes Related to Biological Control. Plants (Basel). 10(12): 2655. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10122655.

[ Links ]

text in

text in